-

The process of oxidation is pivotal in the synthesis of organic moieties, as it facilitates the creation of novel functional moieties or the modification of pre-existing functional groups within molecules. Organic chemistry presents a fascinating inquiry into the realm of amino acids. Polypeptides, proteins, and nucleotides play integral roles in a multitude of metabolic processes, underscoring their essential significance[1−5]. To achieve a more profound comprehension of enzyme kinetics[6], it may be crucial to thoroughly investigate the mechanisms underlying nonenzymatic chemical procedures associated with amino acid oxidation[7−11]. Amino acids have been subjected to oxidation through various experimental conditions, frequently leading to decarboxylation and deamination as outcomes of interaction with diverse reagents[12]. Nonetheless, the diverse reaction systems may progress via distinct mechanisms[13]. Since different oxidants yield different oxidized products, the oxidization of amino acids is noteworthy.

The application of specific metal ions exhibiting elevated valence states, including Ce(IV), Fe(III), V(V), Mn(VII), Cr(VI), and Co(III), as widely recognized oxidizing agents, has been well-documented over a prolonged period[14−16]. Nevertheless, the oxidative transformations utilizing these metal oxidants must be conducted under rather extreme conditions, including elevated concentrations of base or acid and increased temperatures[16,17]. It is significant to emphasize that Cu(III) is among the metal oxidants employed in diverse redox processes. The periodate complex of Cu(III) is often employed as an oxidizing agent[18−21]. The Diperiodatocuprate(III) complex, often designated as DPC, is presently employed thoroughly for redox conversions in eco-friendly solvents. This oxidant is notable for its unique property as a one-electron oxidant, demonstrating a redox potential of around 1.20 V in a basic environment[22]. The application of DPC as an oxidizing agent in alkaline solutions is constrained to select instances owing to its insufficient stability and solubility in aquatic environments[23]. Copper complexes hold considerable significance in the realm of oxidation chemistry, attributed to their widespread occurrence and critical function in biological processes[24]. The intricate equilibrium comprising various Cu(III) species presents a captivating challenge in pinpointing the exact species that facilitates the oxidation process[18−21]. DPC adeptly oxidizes a range of organic compounds, such as amines, amino acids, antibiotics, ketones, and alcohols, within an alkaline environment[25,26]. Nevertheless, the redox behavior of DPC within the micellar environment has not been extensively explored[27−31].

Transition metals' varied oxidation states allow them to catalyze several redox reactions. Transition metal ions like iridium, chromium, palladium, osmium, copper, iron, and ruthenium are highly sought after as catalysts in redox processes[32−34]. Ru(III) functions as a catalyst, thereby facilitating the oxidization of a variety of organic and inorganic constituents. The process of catalysis is contingent upon the setting of the experiment, the oxidizing agent employed, and the properties of the substrate involved[35]. Metal ions have been proven to serve as catalysts through distinct mechanisms, such as forming complexes with the substrate, producing free radicals, or directly oxidizing the reactant. The role of Ru(III) catalysis in redox processes demonstrates a spectrum of complexity, mainly through the formation of various intermediary complexes and the existence of ruthenium's different oxidation states[12].

Surfactants are acquiring significant acceptance across multiple sectors due to their exceptional capacity for self-assembly in solutions and at interfaces[36]. Surfactants are typically organic substances characterized as amphiphilic, meaning each molecule possesses a dual nature, comprising a hydrophobic 'water-repelling' tail and a hydrophilic 'water-attracting' head[37]. Consequently, a surfactant comprises both a hydrophilic component and a hydrophobic counterpart. Surfactants exhibit diffusion in aqueous environments and become adsorbed at the interfaces between water and air, or at the boundary between water and oil when these two substances are combined[37]. At low concentrations, the surfactant exhibits electrolytic properties in its aqueous solution. Micellization occurs in an aquatic environment because of the existence of a substrate that contains both hydrophilic and hydrophobic constituents. The threshold concentration at which micelles initiate their formation is known as the critical micelle concentration (CMC)[38]. The behavior of surfactant molecules varies significantly based on their presence in micelles versus as free monomers, making this phenomenon noteworthy. The micellization procedure depends on several factors, such as the kind of solvent, temperature, pH, additives, and the length of the hydrophobic tail of the surfactant[39]. The micellization of ionic surfactants generally entails two distinct types of interactions: electrostatic interactions associated with polar head groups and hydrophobic interactions linked to nonpolar tails[38]. Micelles are simple spherical supramolecular arrangements formed by amphiphiles in aqueous environments. The micellar system generally exhibits a spatially uniform appearance at a macroscopic scale due to the existence of colloidal-sized aggregates. Nevertheless, they are actually heterogeneous systems at the microscale and function as nanoreactors for a variety of organic reactions[40]. Micelles can influence the rate of a chemical reaction, either accelerating or decelerating it in comparison to a similar reaction conducted in an aquatic media. Aqueous micellar technology is presently employed with considerable efficacy for facilitating a variety of organic reactions within an aqueous micellar environment[41]. The advent of 'green chemistry' has encouraged many scientists to employ water as a solvent, as it is estimated that 80% of waste generated from chemical manufacture comprises organic solvents[42]. Micellar catalysis represents an excellent green approach, as it effectively minimizes energy consumption, waste production, and reliance on organic solvents[43]. Reaction rates investigated in a micellar medium might be faster than those typically reported in organic solvents due to the significantly elevated concentration of reactants within the micelle[44]. Physical chemists have chosen aqueous surfactant solutions as a more sustainable reaction medium because of these advantages and their alignment with the principles of organic synthesis observed in nature. Various surfactant mixtures are used for different applications. Surfactant mixtures have better physicochemical properties than individual surfactants. In solution, surfactant mixtures form mixed micelles. Mixtures of two or more surfactants (micelles) have many advantages over individual surfactants due to synergistic effects[45,46].

The study of micellar catalysis in reactions involving electron transfers has emerged as a fascinating domain for kinetic investigations. A review of the current literature reveals a notable scarcity of attention directed towards the oxidation of organic moieties by DPC within a micellar environment[27−29]. Moreover, the influence of surfactants on the metal-catalyzed oxidization of amino acids by DPC within a micellar environment remains unexplored. Studies have demonstrated that in an alkaline environment, Ru(III) serves as a catalyst for DPC's oxidation of amino acids[34,35]. The significance of these studies lies in their capacity to elucidate the mechanistic roles of amino acids in redox reactions, as well as to identify the species of interest of Cu(III) and the Ru(III) catalyst. Moreover, comprehending how surfactants influence reaction rates enhances the importance of a thorough examination of the title reaction. Furthermore, the kinetic study presented herein will be beneficial for the community engaged in metal-catalyzed electron transfer mechanisms, thereby enhancing the progress within the domain of electron transfer mechanisms. Consequently, this study seeks to investigate the effects of cationic micellar environments on the catalytic oxidization (utilizing Ru3+) of L-leucine by DPC.

-

The kinetic experiments were conducted employing analytical-grade reagents and double-distilled water during the entire investigation. The surfactant utilized, cetylpyridinium chloride (Fisher Scientific, India, 99.0% pure), was of utmost purity. L-leucine (99.0%) was provided by Loba India, which was utilized without any further processing. RuCl3 (Fisher Scientific, India, 99.9% pure) was solubilized in HCl to prepare a standard supply solution of Ru(III). Utilizing EDTA titration, its concentration was ascertained[47]. A systematic process was followed in the preparation and standardization of the copper(III) periodate complex[48,49]. The involvement of the Cu(III) complex was substantiated through the UV–Vis spectrum, which displayed a peak absorbance at 415 nm (Supplementary Fig. S1). The preparation of a stock solution of periodate necessitated the dissolution of a precisely measured quantity of KIO4 (HiMedia India, 99.0% pure) in warm water. The solution was subsequently allowed to attain equilibrium for 24 h before its application. The concentration was ascertained through iodometric analysis[50] while maintaining a neutral pH with the help of a phosphate buffer. The ionic strength of the reacting solutions was upheld through the utilization of KNO3 (HiMedia India, 99.0% pure), whereas KOH (Merck, India, 99.0% pure) was employed to control the pH of the reacting solutions.

Apparatus

-

A T65 UV-visible spectrophotometer (double-beam) manufactured by PG Instruments Limited was applied to measure absorbance at an assigned wavelength. A self-sustaining water circulation system maintained a stable temperature within the cell chamber. A digital pH meter from Ohaus (model OH30057496) was employed to determine the pH of the solution being investigated. The IRTracer-100 FTIR spectrometer (Shimadzu, Japan) was employed for the examination of the ultimate oxidation product.

Kinetic measurements

-

In both aqueous and micellar environments, the oxidization of L-leucine by DPC, facilitated by Ru(III), was observed at a temperature of 298 K employing pseudo-first-order conditions ([L-leucine] > [DPC]). The reactants were subjected to pre-immersion in a thermostat for 30 min to ensure the stability of their temperature throughout each kinetic run. No alterations were made to the absorption results, as neither of the interacting solutions exhibited substantial absorption at 415 nm. The oxidation reaction being examined was performed in an alkaline setting ([OH−] = 0.02 M). The reactants with defined concentrations were meticulously mixed in a specific order: L-leucine, KOH, KNO3, Ru(III), and DPC to commence the oxidation of L-leucine in both aqueous and surfactant environments. The assessment of the reaction's advancement entailed quantifying the reduction in absorbance at 415 nm associated with DPC. Throughout the investigation, a uniform concentration of KIO4 was utilized during the kinetic experiments. An investigation was undertaken to ascertain whether the presence of excess periodate in DPC would induce the oxidation of L-leucine. The findings indicated that KIO4 did not interact significantly within the parameters established for the experiment. The non-linear least squares fitting approach was employed as a metric for calculating the reaction's rate constant (kobs). All experiments were conducted in triplicate.

-

The kinetic investigation on Ru(III) facilitated L-leucine oxidation by Cu(III) in micellar surroundings was conducted through the observation of the decrease in absorption at 415 nm. The reduction of Cu(III) to Cu(II) accounts for the noted decline in absorbance. It was discovered through careful inspection that the brown Cu(III) solution progressively turned light blue. The emergence of Cu(II) species is responsible for this color shift[21,22], which further substantiates the continual progression of the redox reaction. The kinetic study employed both the aqueous and micellar mediums, conducted at 298 K under alkaline conditions with the use of 0.02 M KOH.

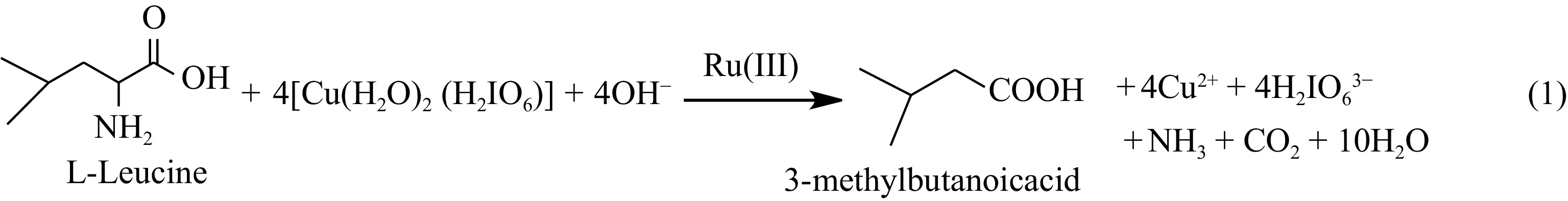

To ascertain the reaction's stoichiometry, the calculated quantity of L-leucine (2.75 × 10−4 M) was permitted to interact with varying mole ratio (1:10) of DPC (2.75 × 10−4 to 2.75 × 10−3 M) at a 0.02 M KOH, 2.5 × 10−6 M [Ru(III)], and 5.5 × 10−4 M [KIO4] within a sealed vessel at a temperature of 298 K. The reaction was permitted to complete at that temperature. Spectrophotometric measurements conducted at 415 nm were utilized to determine the product content. The experimental findings suggested that four moles of DPC are required to oxidize a single mole of L-leucine, as demonstrated in Fig. 1.

Upon completion of the reaction, the resultant mixture was carefully transferred into a round-bottom flask, which was subsequently connected to a fractional distillation apparatus. We took the first distillation product and repeated the distillation process until a single spot was observed on TLC. The distillation product obtained was utilized for further examination. The ultimate outcome of the reaction was identified as 3-methylbutanoic acid, with its identity corroborated through FTIR spectral analysis.

The FTIR spectra of the finished product (Fig. 2), 3-methylbutanoic acid, exhibit absorption peaks at 3,300−2,500 cm−1, 2,967 and 2,878 cm−1, and 1,712 cm−1. These spectral characteristics are associated with the stretching frequencies of the O-H, C-H, and C=O bonds, respectively (Fig. 2). Moreover, the presence of a wide absorption band spanning from 2,500 to 3,300 cm−1 confirms the existence of the -COOH functional group.

A study was undertaken to ascertain the existence of free radicals during the process of oxidation through the application of a polymerization test. The reacting mixture was maintained in an inert atmosphere for a duration of 6 h, utilizing a designated quantity of acrylonitrile scavenger. The introduction of methanol results in the emergence of white solid particles, signifying the existence of free radicals within this reaction. The attempts performed without L-leucine under analogous conditions were unsuccessful, indicating that L-leucine plays a role in the production of free radicals.

Reaction order

-

Upon the amalgamation of the reactants ((L-leucine, KOH, KNO3, Ru(III), IO4−, and DPC), the advancement of L-leucine oxidation was meticulously tracked by computing the absorbance value at 415 nm. The rate constant (kobs) was ascertained by plotting ln(A∞ − At) in relation to time. Where, At signifies the absorbance at a particular moment, while A∞ indicates the absorbance once the reaction has reached completion. The reaction orders were determined by systematically adjusting the concentrations of IO4−, OH−, DPC, Ru(III), and L-leucine one at a time, while keeping the other components constant. The conclusion was derived from the analysis of the slopes of the lnkobs in relation to ln(concentration) plots.

Influence of varying [L-leucine] on the observed rate constant

-

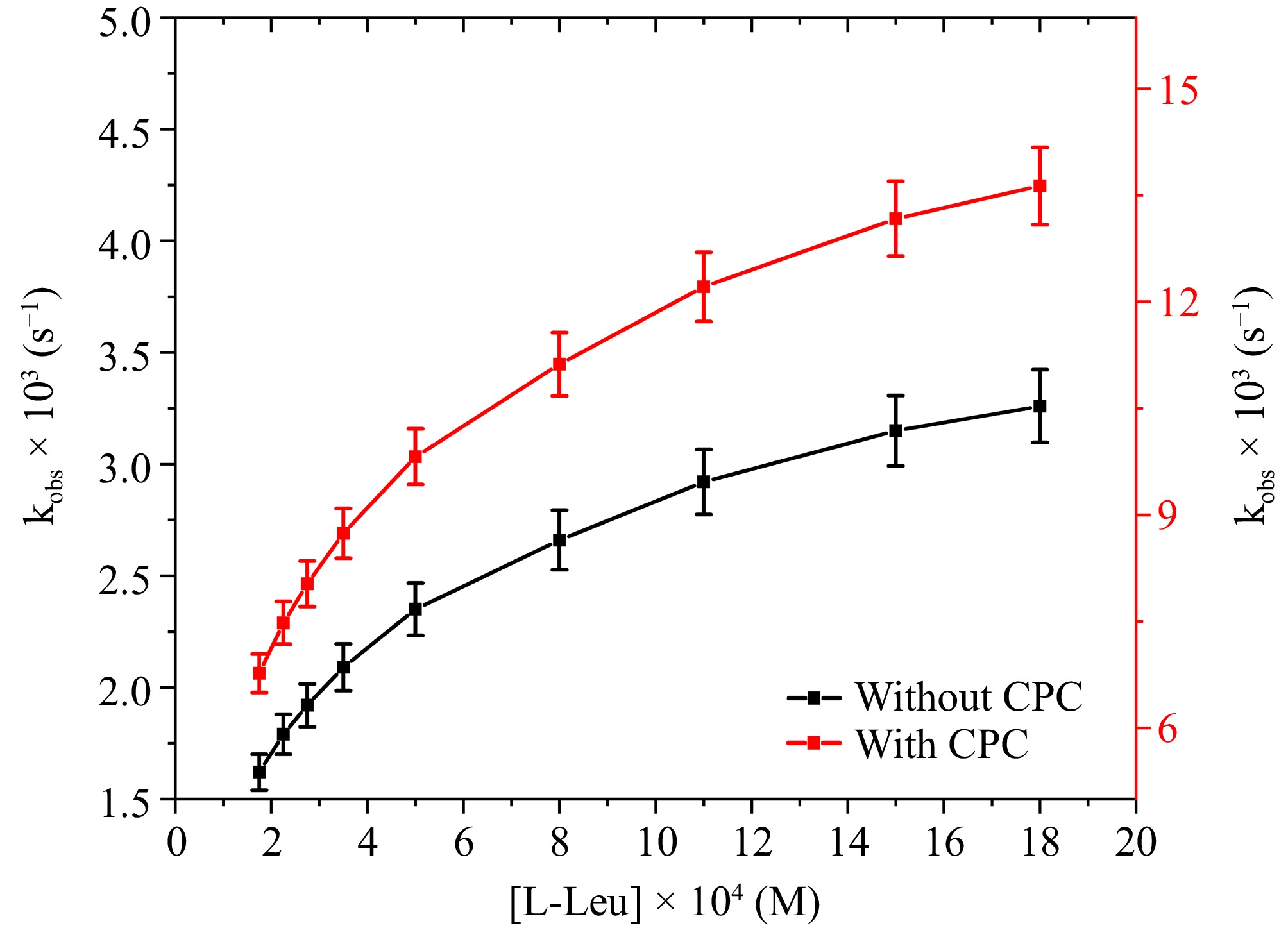

The influence of varying concentrations of L-leucine upon the oxidation rate was examined at a temperature of 298 K ranging from 1.75 × 10−4 to 18.0 × 10−4 M, under the defined OH− concentration conditions. The graph illustrating the correlation between kobs and [L-leucine] (Fig. 3) demonstrates an increase in the reaction rate as [L-leucine] rises. The investigation's findings show that L-leucine exhibits fractional-first-order kinetic behavior in both aqueous and micellar environments (0.32 in the CPC micellar media and 0.30 in the aqueous media). The initial swift increase in reaction rate is probably due to the rapid formation of the intermediate complex between hydroxylated species of Ru(III) and L-leucine, which further reacts slowly with 1 mole DPC in a rate-determining step to give the products as given in Fig. 9. The relatively slower reaction rate at higher [L-leucine] might be due to the lesser availability of Ru(III)[19]. Prior research on the oxidation of amino acids by copper(III) periodate in an alkaline environment, facilitated by Ru(III), demonstrates a comparable trend[15−18]. The micellar environment of CPC demonstrates an accelerated rate of L-leucine oxidization by DPC, facilitated by Ru(III) when contrasted with an aquatic medium.

Figure 3.

The correlation between [L-leucine] and kobs at [DPC] = 1.75 × 10−5 M, [OH−] = 0.02 M, [Ru3+] = 2.5 × 10−6, I = 0.1 M (KNO3), Temp = 298 K, [IO4−] = 5.5 × 10−4 M, [CPC] = 6.0 × 10−3 M.

Influence of varying [OH−] on the observed rate constant

-

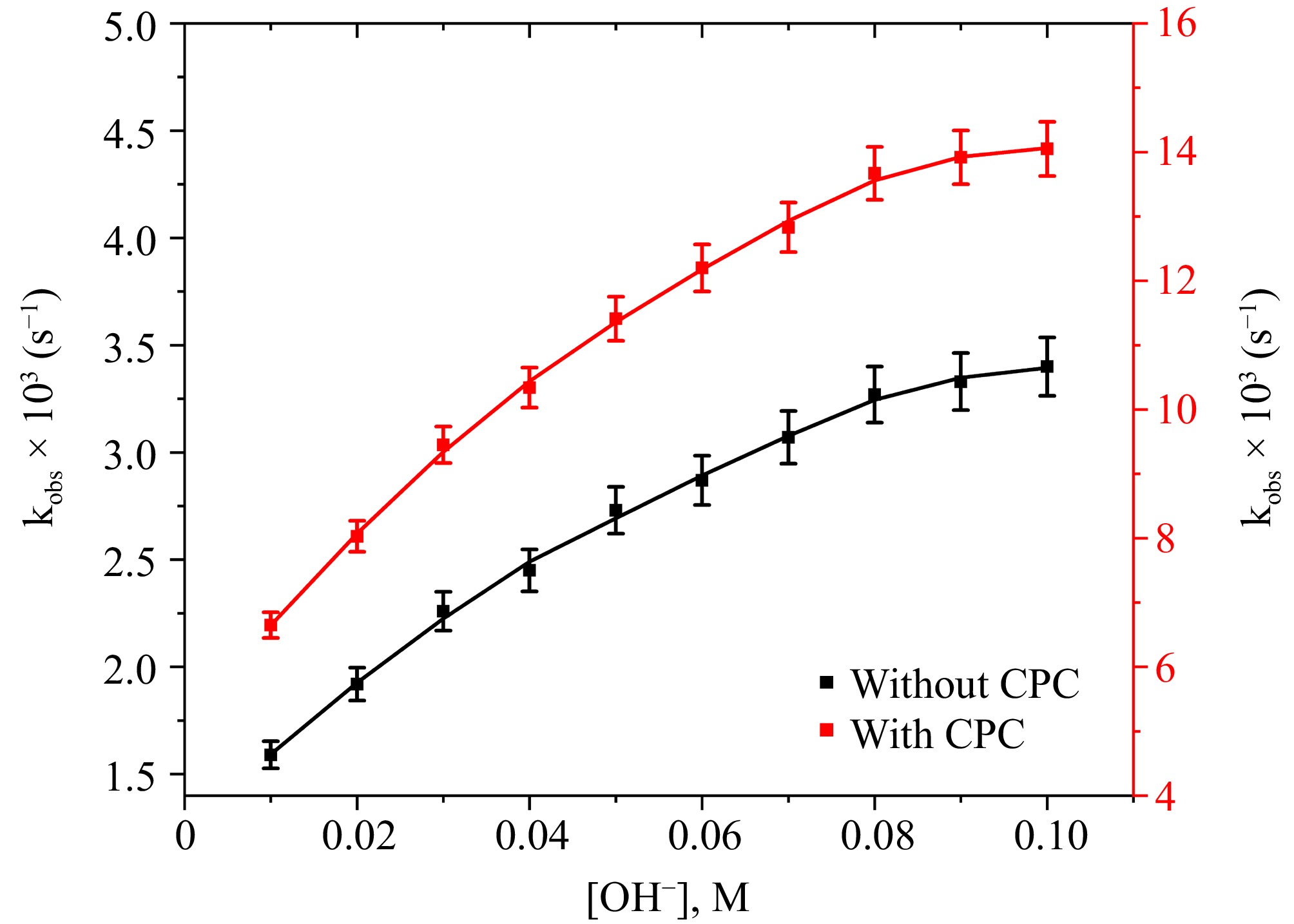

Prior research concerning the oxidization of biological entities via DPC, whether catalyzed or uncatalyzed, has highlighted the considerable importance of OH− in modulating the oxidation rate[18−22]. The research sought to investigate the reaction rate over a spectrum of [OH−] concentrations, from 0.01 to 0.10 M, by computing the rate constant at distinct [OH−] levels. The electron transfer reaction illustrates fractional-first-order kinetic dependence concerning [OH−], as evidenced by the correlation between [OH−] and kobs presented in Fig. 4. The reaction rate is moderate for low OH− concentrations, but it increases precisely as OH− concentration increases within the measured range. The order of OH− was 0.35 in the aqueous medium and 0.39 in the CPC micellar medium. The reduced rate in an aqueous medium at lower pH is attributed to the presence of a less reactive protonated L-leucine. L-leucine exits predominantly in its deprotonated form at higher [OH−]. The presence of only a deprotonated form of reducing agent is liable for the observed slow increase in oxidation rate in a highly alkaline medium[16,17]. Earlier research on copper(III) periodate oxidizing amino acids in an alkaline environment catalyzed by Ru(III) show an identical outcome[16−19]. Figure 4 depicts that CPC micellar media oxidizes L-leucine faster than aqueous media.

Figure 4.

The correlation between [OH−] and kobs at [DPC] = 1.75 × 10−5 M, [L-leucine] = 2.75 × 10−4 M, [Ru3+] = 2.5 × 10−6, I = 0.1 M (KNO3), Temp = 298 K, [IO4−] = 5.5 × 10−4 M, [CPC] = 6.0 × 10−3 M.

Influence of varying [DPC] on the observed rate constant

-

The rate of L-leucine oxidation was assessed by employing optimum conditions of [L-leucine] and [OH−] while maintaining constancy in all other reaction parameters. The calculation of the oxidation rate was conducted with reference to [DPC] across the concentration ranging from 1.75 × 10−5 to 17.5 × 10−5 M. The calculated kobs values for each [DPC], as presented in Table 1, clearly indicate that the examined spectrum of [DPC] demonstrates first-order kinetic behavior in both aqueous and micellar environments. Past research on copper(III) periodate oxidizing amino acids in an alkaline environment catalyzed by Ru(III) shows a similar result[15−19].

Table 1. Effect of variation of [DPC] on rate constant (kobs) at [L-leucine] = 2.75 × 10-4 M, [OH−] = 0.02 M, [Ru3+] = 2.5 × 10-6, I = 0.1 M (KNO3), Temp = 298 K, [IO4−] = 5.5 × 10−4 M, [CPC] = 6.0 × 10−3 M.

[DPC] × 105 (M) kobs × 103 (s−1) (without CPC) kobs × 103 (s−1) (with CPC) 1.75 1.92 ± 0.06 8.03 ± 0.16 3.0 1.98 ± 0.09 8.09 ± 0.19 6.0 2.01 ± 0.05 7.95 ± 0.21 9.0 1.96 ± 0.07 8.11 ± 0.11 12.0 1.86 ± 0.08 7.92 ± 0.16 15.0 1.89 ± 0.06 8.13 ± 0.18 17.5 1.95 ± 0.04 8.07 ± 0.14 Influence of varying [IO4−] on oxidation rate

-

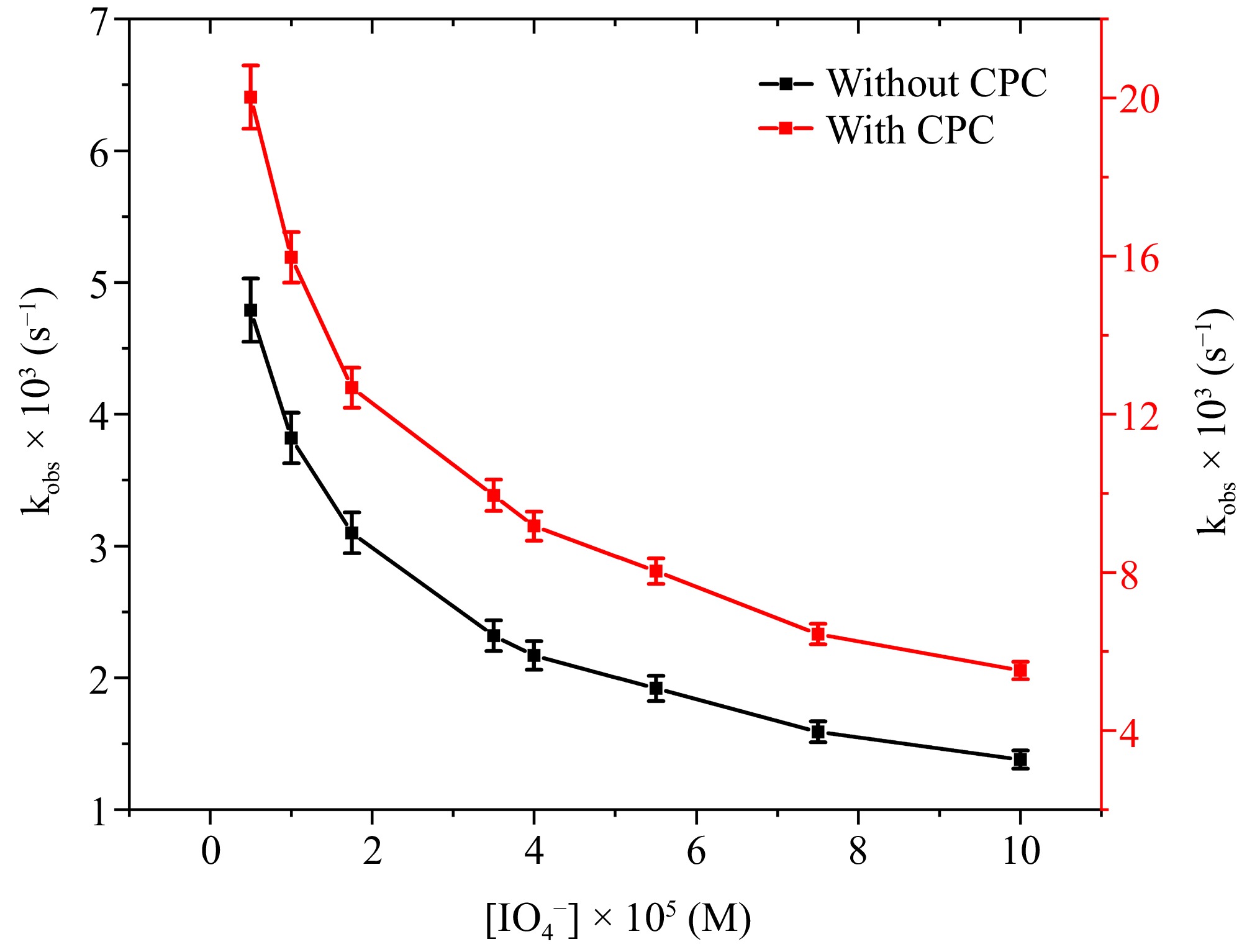

To explore the possible involvement of IO4− in the oxidation process, the effects of introducing IO4− into the reacting mixture were evaluated, maintaining all other reaction parameters constant. The reaction rate demonstrated a decrease with the increasing concentration of IO4− (Fig. 5). In an aqueous environment, the order concerning IO4− was determined to be a negative fractional value of −0.42, while in a CPC micellar environment, it was recorded as −0.45. The micellar environment of CPC exhibits a heightened rate of Ru(III)-catalyzed L-leucine oxidation by DPC when contrasted with the observations made in an aqueous medium.

Figure 5.

The correlation between [IO4−] and kobs at [DPC] = 1.75 × 10−5 M, [L-leucine] = 2.75 × 10−4 M, [OH−] = 0.02 M, [Ru3+] = 2.5 × 10−6, I = 0.1 M (KNO3), Temp = 298 K, [CPC] = 6.0 × 10−3 M.

Influence of varying [Ru(III)] on oxidation rate

-

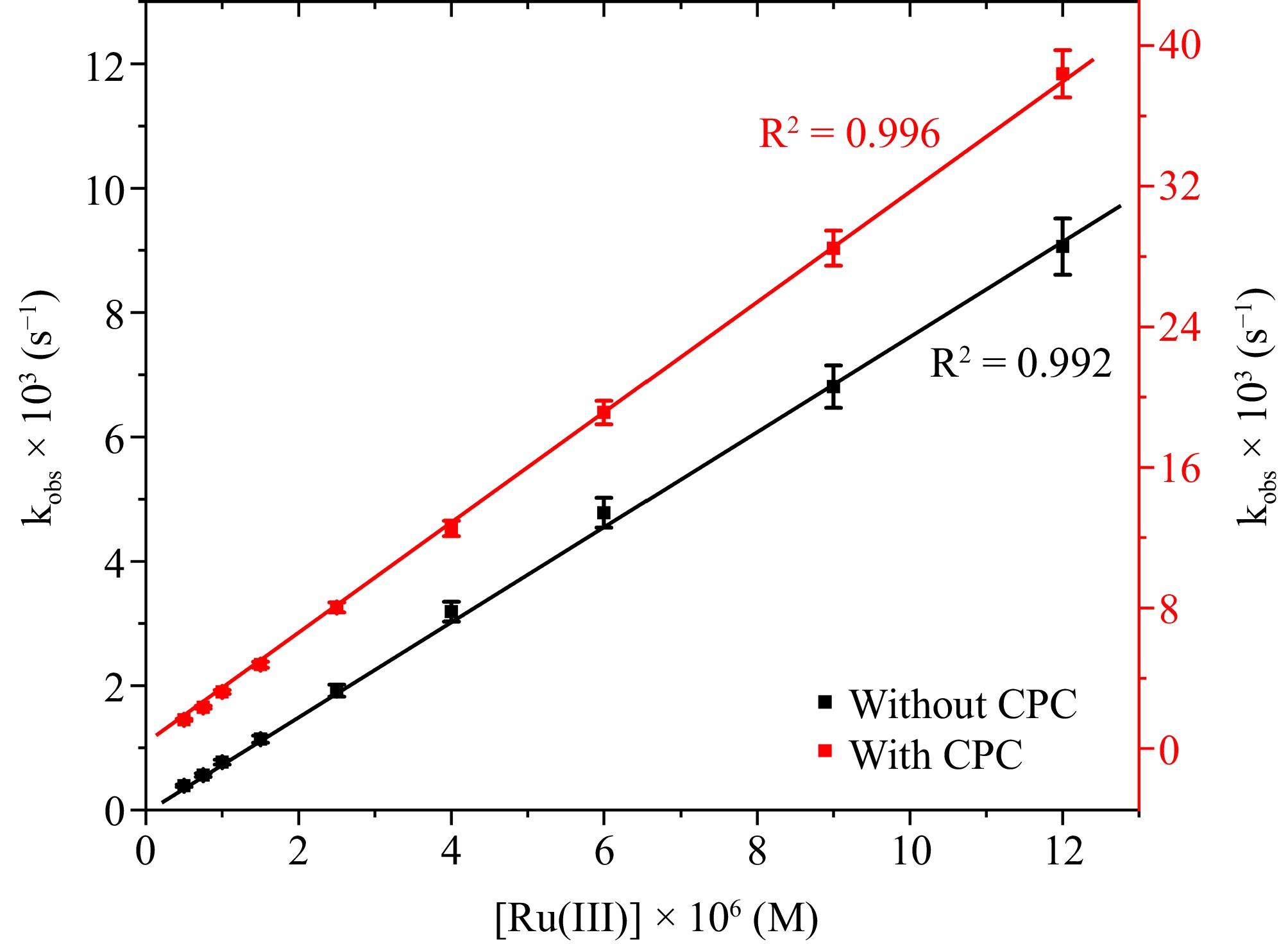

In light of the prospective utilization of Ru3+-catalyzed oxidation reactions for the trace-level detection of Ru(III), it is essential to evaluate the influence of [Ru3+] on the oxidation rate. In the DPC oxidation of L-leucine, we utilized three different metal catalysts: Ru(III), Co(III), and Fe(II).

Results show that the catalytic activity of Ru(III) is much higher compared to Co(III), and Fe(II) (Supplementary Table S1). So the detailed kinetic investigation has been performed with Ru(III). The research concentrated on analyzing the oxidation rate within the range of 0.5 × 10−6 to 1.2 × 10−5 M [Ru(III)] under optimal reaction conditions. This was accomplished by calculating the rate constant (kobs) for different Ru(III) concentrations. Figure 6 illustrates a linear relationship between kobs and [Ru(III)], indicating first-order kinetics dependent on [Ru(III)] throughout the concentration range examined.

Figure 6.

The correlation between [Ru(III)] and kobs at [DPC] = 1.75 × 10−5 M, [L-leucine] = 2.75 × 10−4 M, [OH−] = 0.02 M, I = 0.1 M (KNO3), Temp = 298 K, [IO4−] = 5.5 × 10−4 M, [CPC] = 6.0 × 10−3 M.

Influence of varying [KNO3] on oxidation rate

-

Using potassium nitrate to regulate the reaction media's ionic strength (I) between 0.05 and 0.50 M, the impact of I on oxidation rate was examined. The other variables associated with the reaction were held unaltered at [IO4−] = 5.5 × 10−4 M, [CPC] = 6.0 × 10−3 M, [DPC] = 1.75 × 10−5 M, Temperature = 298 K, [L-Leu] = 2.75 × 10−4 M, [OH−] = 0.02 M, and [Ru3+] = 2.5 × 10−6. The reported consistency in oxidation rate regardless of KNO3 concentration, as illustrated in Table 2, suggests a zero salt effect. The enduring nature of the rate constant, independent of ionic strength, suggests the participation of positively charged ions (L-Leucine-Ru complex) and neutral Cu(III) species (MPC) in the critical rate-determining step. Previous studies regarding the metal-catalyzed oxidation of organic moieties by MPC further corroborate the zero salt effect[18−20,22,34,35].

Table 2. Effect of variation of [Electrolyte] on rate constant (kobs) at [DPC] = 1.75 × 10−5 M, [L-leucine] = 2.75 × 10−4 M, [OH−] = 0.02 M, [Ru3+] = 2.5 × 10−6, Temp = 298 K, [IO4−] = 5.5 × 10−4 M, [CPC] = 6.0 × 10−3 M.

I (KNO3), M kobs × 103, s−1

(without CPC)kobs × 103, s−1

(with CPC)0.05 2.01 ± 0.09 8.07 ± 0.14 0.10 1.92 ± 0.06 8.03 ± 0.16 0.20 1.98 ± 0.04 8.00 ± 0.19 0.30 1.97 ± 0.10 7.97 ± 0.20 0.40 1.86 ± 0.08 7.94 ± 0.21 0.50 1.93 ± 0.07 8.03 ± 0.12 Influence of varying temperature on oxidation rate

-

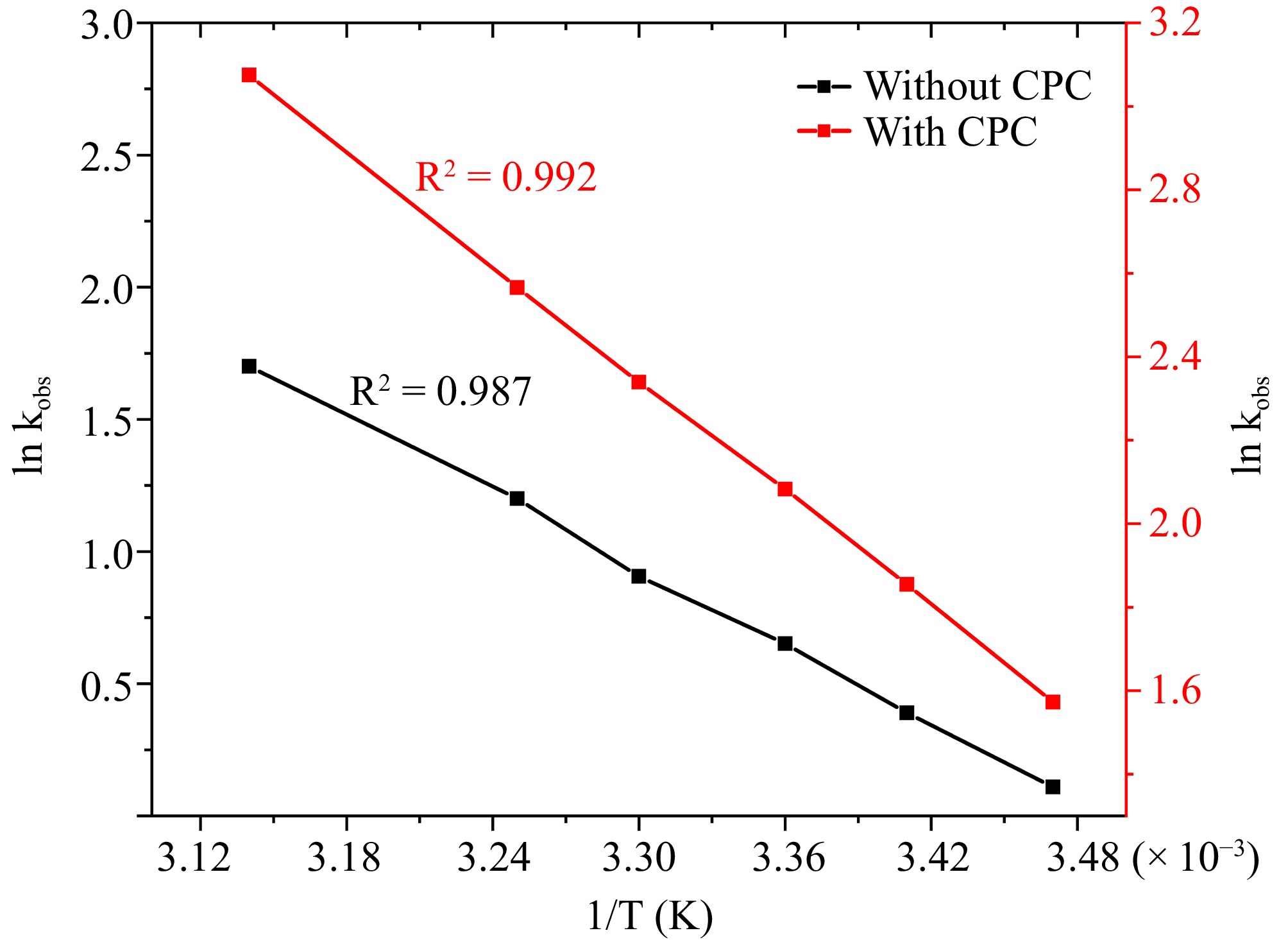

The research investigated the influence of temperature on the rate of oxidization within a spectrum of 288 to 318 K. The investigation into the reaction at elevated temperatures was overlooked due to apprehensions regarding the potential deterioration of the end product and the exceedingly rapid reaction rate. The Arrhenius equation, which states that the reaction rate escalates with temperature, was followed by the reaction as expected. At a temperature of 298 K, the reaction demonstrates a moderate rate of advancement. Therefore, it is recommended that a temperature of 298 K be considered the ideal option for pursuing additional investigations into the reaction system. The Arrhenius equation, by plotting lnkobs against 1/T (Fig. 7), was employed for determining the energy of activation (Ea) and activation enthalpy (ΔH#) values. They were discovered to be 40.32 ± 2.11 k·J·mole−1, 37.84 ± 1.86 k·J·mole−1 in an aqueous environment, 37.61 ± 1.96 k·J·mole−1, and 35.13 ± 1.71 k·J·mole−1 in CPC micellar medium respectively.

Figure 7.

The correlation between temperature and kobs at [DPC] = 1.75 × 10−5 M, [L-leucine] = 2.75 × 10−4 M, [OH−] = 0.02 M, [Ru3+] = 2.5 × 10−6, I = 0.1 M (KNO3), [IO4−] = 5.5 × 10−4 M, [CPC] = 6.0 × 10−3 M.

Influence of varying [CPC] on oxidation rate

-

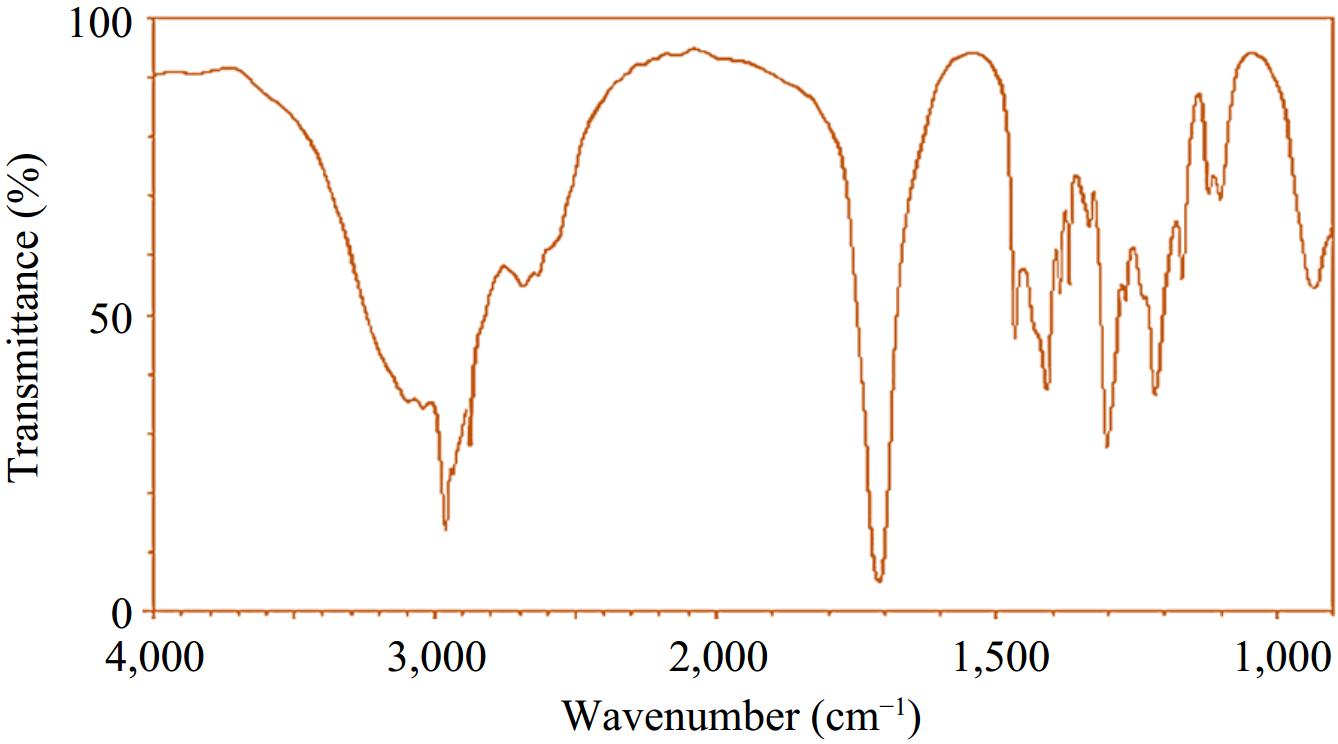

Surfactants can facilitate rate enhancement while also ensuring the uniform distribution of organic reactants within an aqueous environment, depending on their charge characteristic (anionic, neutral, and cationic)[14]. The selection of the cationic surfactant CPC was based on its non-interaction with DPC, in contrast to CTAB, which demonstrated interaction with DPC, as indicated by the noticeable alteration in solution color[27]. The concentration of CPC was systematically adjusted from 0.25 × 10−4 M to 10.0 × 10−4 M, while maintaining other parameters constant, to assess its effect on the oxidation rate. The plot of [CPC] against kobs presented in Fig. 8 indicates a substantial enhancement in the reaction rate as [CPC] rises to 6.0 × 10−4 M, which aligns closely with the CMC of CPC. Subsequent to this, the oxidation rate continues to increase throughout the ranges of the examined [CPC], albeit more slowly. In the observed reaction condition, the computed CMC of CPC is 4.84 × 10−4 M, which is marginally less than the value recorded in the aquatic environment. The convergence of the two linear trajectories on the kobs versus [CPC] graph elucidates this point.

-

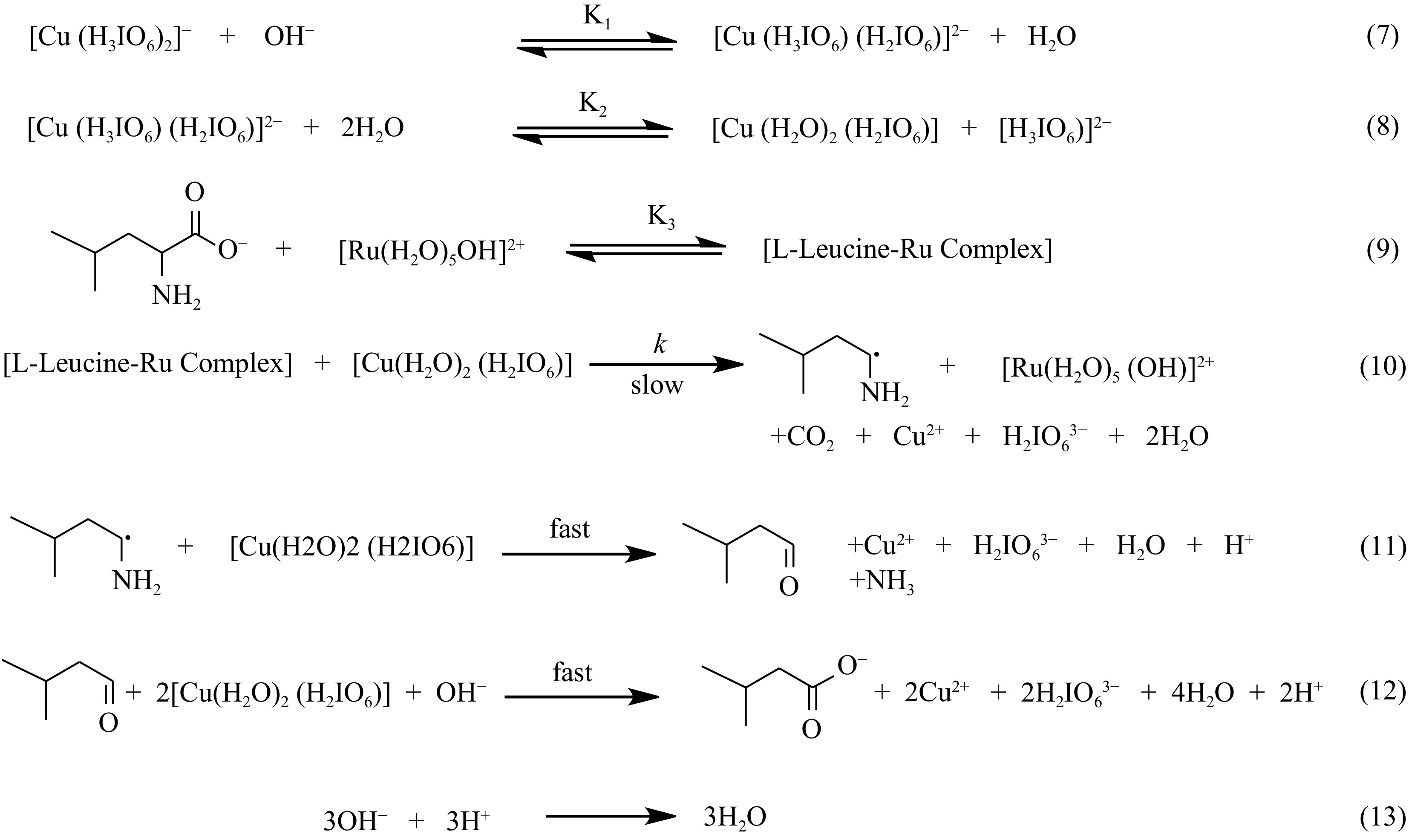

Reports indicate that the copper(III) periodate complex, exhibiting solubility in water, is represented by the formula [Cu(HIO6)2(OH)2]7−[51]. Periodate experiences several equilibrium stages, as demonstrated by Eqns (2)−(4), depending on the pH of the medium[52].

$ \mathrm{H}_{5} \mathrm{IO}_{6} { \xrightleftharpoons{\;\;\;\;\; }} \mathrm{H}_{4} \mathrm{IO}_{6}^{-}+\mathrm{H}^{+} $ (2) $ \mathrm{H}_{4} \mathrm{O}_{6}^{-} \overset{\;}{\rightleftharpoons} \mathrm{H}_{3} \mathrm{IO}_{6}^{2-}+\mathrm{H}^{+} $ (3) $ \mathrm{H}_{3} \mathrm{IO}_{6}^{2-} \overset{\;}{\rightleftharpoons} \mathrm{H}_{2} \mathrm{IO}_{6}^{3-}+\mathrm{H}^{+} $ (4) In an acidic milieu, periodic acid exists in the form of H5IO6, whereas at a pH approaching 7, it is represented as H4IO6−. Consequently, in an alkaline context, it is expected that the predominant species will be H2IO63− and H3IO62−. Furthermore, periodate will probably undergo dimerization at elevated concentrations. Nonetheless, given the conditions applied in this kinetic study, the emergence of such a species is minimal[20−22]. Consequently, based on Eqns (5) and (6), the soluble copper(III) periodate complex exists in the forms of either monoperiodatocuprate(III) (MPC), [Cu(H2IO6)(H2O)2], or diperiodatocuprate(III) (DPC), [Cu(H2IO6)(H3IO6)]2−, at the pH utilized for the current study[53].

$ {\left[\mathrm{Cu}\left(\mathrm{H}_{3} \mathrm{IO}_{6}\right)_{2}\right]^{-}+\mathrm{OH}^{-} \overset{\mathrm{K}_{1}}{\rightleftharpoons}[\mathrm{Cu}\left(\mathrm{H}_{3} \mathrm{IO}_{6}\right)\left(\mathrm{H}_{2} \mathrm{IO}_{6}\right)]^{2-}+\mathrm{H}_{2} \mathrm{O}} $ (5) $ {\left[\mathrm{Cu}\left(\mathrm{H}_{3} \mathrm{IO}_{6}\right)\left(\mathrm{H}_{2} \mathrm{IO}_{6}\right)\right]^{2-}+2 \mathrm{H}_{2} \mathrm{O} \overset{\mathrm{K}_{2}}{\rightleftharpoons}\left[\mathrm{Cu}\left(\mathrm{H}_{2} \mathrm{O})_{2}\left(\mathrm{H}_{2} \mathrm{IO}_{6}\right)\right]+\left[\mathrm{H}_{3} \mathrm{IO}_{6}\right)\right]^{2-}} $ (6) The decrease in the rate with an increase in periodate concentration suggests that the displacement of a ligand periodate takes place to give a free periodate and MPC species from [Cu(H2IO6)(H3IO6)]2− [Eqn (6)]. It may be expected that a lower periodate complex such as monoperiodatocuptrate(III) (MPC) is more important in the reaction than the DPC. The inverse fractional order in periodate might also be due to this reason. Therefore, MPC might be the main reactive form of the oxidant [17−20].

Ru(III) has shown significant effectiveness as a catalyst across a diverse array of redox processes, applicable in both acidic and alkaline conditions[10,14,21,22]. In an alkaline milieu characterized by [OH−] > [Ru(III)], Ru(III) predominantly manifests as its hydroxylated form ([Ru(H2O)5OH]2+) [54]. Consequently, [Ru(H2O)5OH]2+ is regarded as the active form of Ru(III), even in an alkaline CPC milieu.

The findings showed that while the addition of periodate decreased the oxidation rate, the addition of OH− boosted it. The catalyst [Ru(III)] and [DPC] exhibited a direct influence (first-order) on the oxidation rate, whereas a more intricate relationship (fractional order) was noted for [OH−] and [L-leucine]. In the context of Ru(III) catalyzed oxidation of L-leucine within an alkaline milieu, a proposed Fig. 9 has been presented to elucidate the observed orders. This scheme considers L-leucine in its anionic form.

Considering the observed influence of periodate on the rate of oxidation. The species of importance pertaining to the Cu(III) periodate complex is designated as monoperiodatocuprate(III) MPC. The results demonstrate that the rate of oxidation diminishes as the concentration of periodate rises, while it escalates with a hike in alkali content. This illustrates the existence of multiple copper(III) periodate complexes, as depicted in Eqns (5) and (6). The interaction among the positively charged ions (L-leucine-Ru complex) and neutral species (MPC) in Fig. 9 can be explained qualitatively by a zero salt effect, as shown by the consistency in oxidation rate with rising [KNO3]. This proposes further substantiation for the existence of MPC as an active variant of copper(III) periodate, along with the suggested mechanism. Earlier studies on the oxidation of amino acids by copper(III) periodate in an alkaline environment catalyzed by Ru(III) also support the proposed mechanism[18−21].

The results demonstrate that the L-leucine oxidation by DPC in an alkaline environment, facilitated by Ru(III), transpires through a series of interrelated stages that lead to the emergence of an L-leucine-Ru intermediate complex (C1), in which L-leucine interacts with Ru(III), yielding a complex (C1) that is soluble in water. It is plausible that the L-leucine-Ru complex will manifest during the equilibrium phase, as the oxidation rate exhibits a fractional-first-order correlation with [L-leucine]. The subsequent step, which establishes the rate, encompasses the interaction among the complex C1 and MPC, leading to the generation of free radical species of L-leucine. This reaction leads to the restoration of the catalyst and the formation of Cu(II). The 3-methylbutanal is produced as a consequence of the rapid reaction between the free radical and MPC. Additionally, the 3-methylbutanal reacts with two additional MPC molecules, resulting in the production of 3-methylbutanoic acid as the final product.

The rate law for the suggested plan can be elucidated in the following manner:

$ \mathrm{R}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{e}\;\mathrm{o}\mathrm{f}\;\mathrm{R}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{c}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{n}=-\dfrac{\mathrm{d}\mathrm{ }\left[\mathrm{D}\mathrm{P}\mathrm{C}\right]}{\mathrm{d}\mathrm{t}}=\mathrm{k}\left[\mathrm{C}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{m}\mathrm{p}\mathrm{l}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{x}\right]\left[\mathrm{C}\mathrm{u}{\left({\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{O}\right)}_{2}\right({\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{I}\mathrm{O}}_{6}\left)\right] $ (14) Considering the low concentrations of periodate and L-leucine employed in this work, the ultimate rate law will be (derivation in the Supplementary Data S1),

$\begin{split}& \mathrm{R}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{e}=\\&{\dfrac{\mathrm{k}{\mathrm{K}}_{1}{\mathrm{K}}_{2}{\mathrm{K}}_{3}[\mathrm{L}-\mathrm{l}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{u}\mathrm{c}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{e}]\mathrm{ }\left[\mathrm{R}\mathrm{u}\right(\mathrm{I}\mathrm{I}\mathrm{I}\left)\right]\mathrm{ }\left[\mathrm{D}\mathrm{P}\mathrm{C}\right]\mathrm{ }\left[{\mathrm{O}\mathrm{H}}^-\right]}{\left[{\mathrm{H}}_{3}{\mathrm{I}\mathrm{O}}_{6}^{2-}\right]\mathrm{ }+{\mathrm{K}}_{1}\left[{\mathrm{O}\mathrm{H}}^-\right]\left[{\mathrm{H}}_{3}{\mathrm{I}\mathrm{O}}_{6}^{2-}\right]\mathrm{ }+{\mathrm{K}}_{1}{\mathrm{K}}_{2}\left[{\mathrm{O}\mathrm{H}}^-\right]\mathrm{ }+{\mathrm{K}}_{1}{\mathrm{K}}_{2}{\mathrm{K}}_{3}[\mathrm{L-}\mathrm{l}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{u}\mathrm{c}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{e}]\left[{\mathrm{O}\mathrm{H}}^-\right]}}\end{split}$ (15) The mentioned rate law delineates the entirety of the recorded kinetic order concerning various reaction parameters.

Role of surfactant (CPC) on oxidation rate

-

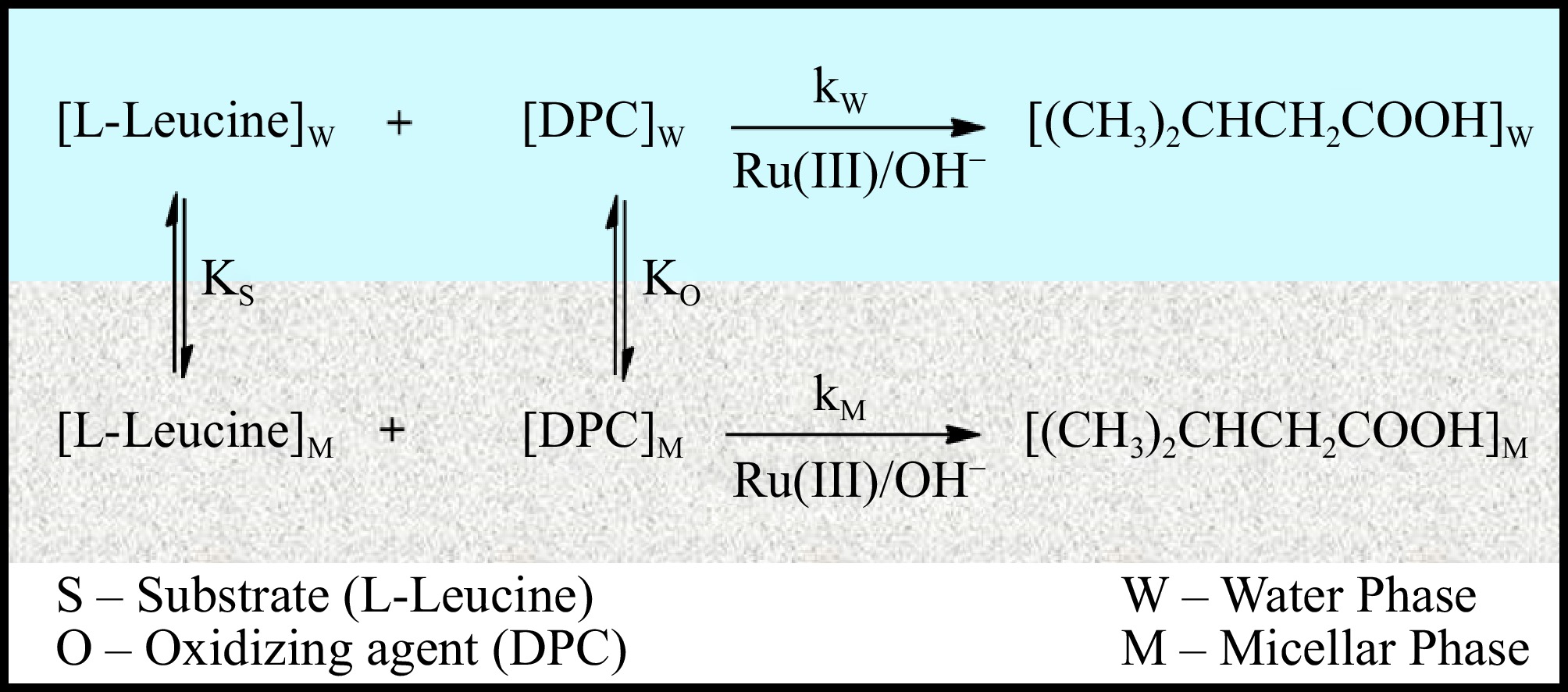

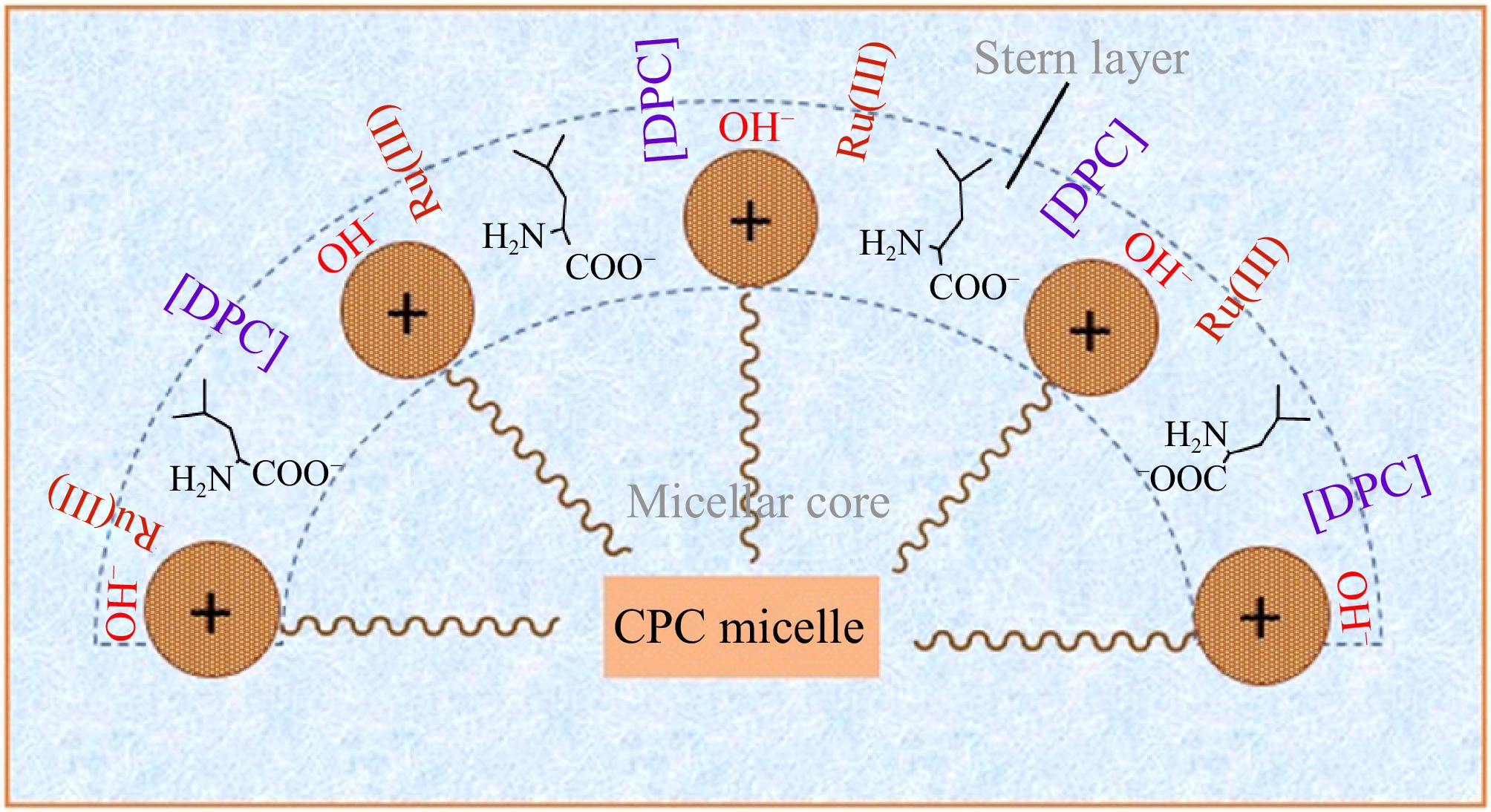

The dispersion of reacting molecules within the micellar and aqueous pseudophases significantly influences the advancement of chemical reactions occurring in a micellar environment. Due to these inherent distinctions, these rates may be diminished or expedited[55−57]. Comprehending the interactions among various components and their influence on the reaction rate is critical. The electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions of the surfactant aggregates with molecules of reactants are of considerable importance, along with the alterations they provoke in the adjacent water molecules. At concentrations below the critical micelle concentration, the monomers of surfactant exhibit catalytic properties. The formation of catalytic micelles develops via the clustering of substrate molecules and monomeric surfactants, leading to an enhanced reaction rate. Surfactant-facilitated reactions are significantly impacted by premicellar conditions[58,59]. The substrate in premicellar complexes exhibits a higher reactivity compared to micellar aggregates. The initial enhancement in reaction rate with [CPC] can be attributed to the establishment of a premicellar complex[12,14]. Following attaining the critical micelle concentration, the premicellar structures disintegrate, which results in the emergence of micelles[60]. This procedure efficiently sustains the oxidation rate.

The surfactant displays an astonishing capability to generate nanoscale micelles and promote the inclusion of all participating components within the CPC micellar solution, thus ensuring a seamless and boosted reaction. Cetylpyridinium chloride (CPC), a cationic surfactant, develops micelles distinguished by a positively charged exterior. Consequently, cationic moieties ([Ru(H2O)5OH]2+) must be prevented from approaching the substrate inside the stern layer, along with the micellar interface[61]. It is plausible to infer that cationic species will experience hydroxylation in an alkaline milieu, resulting in their neutralization. Under the influence of OH−, these neutral entities are now enabled to engage with the surfactant through ion-dipole interactions and hydrogen bonding[10]. In an alkaline CPC micellar environment, the highly positive-charged surface of the micelles facilitates the unobstructed approach of neutral MPC and Ru(III), along with negatively charged OH− ions, towards the L-leucine moiety in the stern layer, free from electrostatic repulsion, as depicted in Fig. 10. In contrast to an aqueous medium, all interacting molecules viz. MPC, L-leucine, OH− ions, and Ru(III), are observed to approach one another within the stern layer of the CPC micelle. This results in an increase in the effective collision frequency among the molecules participating in the reaction, thereby enhancing the oxidation rate. The presence of CPC significantly improves and accelerates the Ru(III) catalyzed L-leucine oxidation by DPC within an alkaline milieu.

Figure 10.

Conceptual illustration of Ru(III) mediated L-leucine Oxidation by DPC in CPC micellar medium.

The pseudophase model (Fig. 11) offers a compelling framework for elucidating the Ru(III) catalyzed L-leucine oxidation by DPC within aquatic micellar situations. The diagram illustrates that KO and KS denote the distribution coefficients of DPC and L-leucine as they partition between the micellar and aqueous pseudophases. This approach facilitates the linkage of data to ascertain the oxidation rate constants and the relative quantity of reactants (DPC and L-leucine) throughout the pseudophases. The pseudophase model provides a thorough explanation of the overall reaction rate, which is dictated by the sum of the rates from each distinct pseudophase. In this case, L-leucine and DPC are dispersed out in both the aqueous and micelles phases. The notably elevated rates recorded in CPC micellar media (kM = 8.03 × 10−3 s−1) in contrast to those in aqueous medium (kW = 1.92 × 10−3 s−1) allows for an exploration and comprehension of the mechanistic distinctions between the two environments. The difference in the oxidation rate of L-leucine in micellar versus aqueous phases serves as compelling evidence for the distribution of reactive species across these two distinct environments. The more pronounced elevation in rate constant values within the micellar phase, as opposed to the aqueous phase, suggests that the micellar phase exhibits a greater substrate concentration.

-

This study enhances our understanding of the metal-facilitated oxidization of amino acids by DPC within a micellar context. Throughout the range of concentrations analyzed, the oxidation reaction demonstrates fractional-first-order kinetic dependence on [L-leucine], alongside first-order dependence on [Ru(III)] and [DPC]. The persistent rate of oxidation observed in the presence of electrolytes serves as compelling evidence of a zero salt effect. OH− is pivotal in the reaction and conforms to the principles of fractional-first-order kinetics. The noted reduction in reaction rate upon the introduction of IO4−, coupled with the zero salt effect, strongly indicates the participation of monoperiodatocuprate(III) as an oxidizing agent. Surfactants, fascinating chemical compounds, significantly accelerate the rate of numerous reactions. For decades, metals in combination with surfactants have been employed to enhance the rate of synthetic organic processes. The Ru(III) catalyzed L-leucine oxidation by DPC in an aqueous alkaline environment demonstrates significant efficacy. The integration of CPC and Ru(III) significantly improves the reaction rate, providing a more pronounced catalytic effect compared to Ru(III) alone. The CPC micellar environment promotes an enhancement of approximately four times in the Ru(III) catalyzed L-leucine oxidation. The increased concentration of reactants in the CPC micellar pseudophase, in comparison to the aqueous pseudophase, as outlined in the pseudophase model, further corroborates the rate enhancement facilitated by CPC micelles. Consequently, in the context of the L-leucine oxidation process utilizing (DPC), CPC demonstrates remarkable compatibility with Ru(III).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: investigation: Srivastava A, Srivastava Nitin, Padhy RK; conceptualization, statistical analysis: Srivastava A; methodology, experimental, graphical work: Srivastava Nitin; formal analysis: Padhy RK, Srivastava Neetu; supervision: Srivastava Neetu; draft manuscript preparation: Srivastava A, Padhy RK, Srivastava Neetu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The supporting datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 Effect of different metal catalyst on rate constant (kobs) at [DPC] = 1.75 × 10−5 M, [L-leucine] = 2.75 × 10−4 M, [OH-] = 0.02 M, I = 0.1 M (KNO3), Temp = 298 K, [IO4−] = 5.5 × 10−4 M, [CPC] = 6.0 × 10−3 M.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 UV-Vis spectrum of the reacting solution indicating the presence of Cu(III) peak at 415 nm at [DPC] = 1.75 × 10−5 M, [OH−] = 0.02 M, [L-leucine] = 2.75 × 10−4 M, [Ru3+] = 2.5 × 10−6, I = 0.1 M (KNO3), Temp = 298 K, [IO4−] = 5.5 × 10−4 M, [CPC] = 6.0 × 10−3 M.

- Supplementary Date S1 Derivation of Rate law.

- Supplementary Data 1

- Supplementary Data S1

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Srivastava A, Srivastava N, Padhy RK, Srivastava N. 2025. Rate enhancement of the Ru(III) facilitated oxidation of L-leucine by Cu(III) periodate in CPC micellar medium: a kinetic and mechanistic approach. Progress in Reaction Kinetics and Mechanism 50: e008 doi: 10.48130/prkm-0025-0008

Rate enhancement of the Ru(III) facilitated oxidation of L-leucine by Cu(III) periodate in CPC micellar medium: a kinetic and mechanistic approach

- Received: 16 January 2025

- Revised: 27 March 2025

- Accepted: 08 April 2025

- Published online: 13 May 2025

Abstract: Amino acid oxidation is fascinating because different oxidants produce diverse compounds. No research has examined how metal catalysts affect amino acid oxidation by diperiodatocuprate(III) (DPC) in micellar environments. This research is crucial to understanding amino acids in redox processes and identifying active species of Ru(III) and DPC. The present study will evaluate how cationic surfactant affects Ru(III)-facilitated L-leucine (L-Leu) oxidation utilizing DPC in an alkaline medium. The progression of the reaction has been evaluated using the pseudo-first-order scenario as a metric for [OH−], [DPC], ionic strength, [L-leucine], [Ru(III)], [IO4−], [Surfactant], and temperature. The interaction between DPC and L-leucine occurs stoichiometrically at a ratio of 4:1. Throughout the range of concentrations analyzed, the observed reaction demonstrates a kinetic order that is less than one concerning both [OH−] and [L-leucine], exhibits negative fractional-order with respect to [IO4−], and shows first-order dependence on [Ru(III)] and [DPC]. The consistent oxidation rate observed with the addition of electrolytes suggests a zero salt effect. Experimental results indicate that monoperiodatocuprate(III) (MPC) is the main Cu(II) species. Ru(III) enhances the oxidation rate by forming an L-Leucine-Ru(III) complex, which interacts with MPC to create a free radical intermediate which is eventually converted into a product. The oxidation rate is markedly increased by Ru(III) solution acting as a catalyst at ppm concentration. The micellar media of cetylpyridinium chloride (CPC) significantly accelerates the rate of the desired reaction, achieving an enhancement of fourfold. The compatibility of CPC with Ru(III) for the oxidation of L-leucine utilizing DPC is notably remarkable.

-

Key words:

- Diperiodatocuprate(III) /

- L-leucine /

- Micellar medium /

- Ru(III) catalyzed /

- Oxidation /

- Surfactant