-

Obesity is a global health problem, which has posed a great threat to human health[1]. The occurrence of obesity is affected by many factors. When the body's energy intake exceeds energy consumption, excess energy is stored in various fat reservoirs, causing an increase in BMI and obesity[2]. At present, obese patients mainly take weight-loss drugs, lipid-lowering drugs, diet, surgery, and other means to reduce fat and weight, but the side effects are obvious[3]. Existing lipid-lowering and weight-loss drugs such as orlistat and statins not only cause fat-soluble vitamin deficiency but also cause adverse reactions such as muscle and liver damage[4,5], which cannot meet people's demand for healthy weight loss. Therefore, the search for efficient and low-side effects of lipid-lowering weight loss programs has attracted the attention of obese people.

The negative impact of obesity caused by a high-fat diet on the body is not simply the increase in body size. Studies have shown that long-term acceptance of excessive lipids can cause dyslipidemia and cause hyperlipidemia[6]. Excessive lipid metabolism increases the burden on the liver, manifested by increased activity of alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase[7]; it also causes lipid peroxidation to cause a secondary attack on the liver[8]. The occurrence of obesity is closely related to intestinal flora[9]. Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes have been recognized as biomarkers indicating obesity susceptibility. Studies have reported that the ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes (F/B) in the intestine of obese individuals is higher[10,11]. These results suggest that improving the liver function, oxidative stress level, and intestinal flora composition of individuals on a high-fat diet may be a potential mechanism for reducing obesity.

Pu-erh tea has attracted attention because of its unique flavor and various health functions. A large number of cytological studies and animal experiments have confirmed that Pu-erh tea has antioxidants[12], hypoglycemic lipids[13], enhances immunity[14], reduces metabolic disorders[15,16], protects the liver[17], and other health functions. In addition, a large number of scholars at home and abroad have shown that Pu-erh tea has the effect of reducing fat and weight loss when exploring the nutritional and health effects of Pu-erh tea[18−20]. The health effect of Pu-erh tea on lipid-lowering and weight loss largely depends on the characteristic component theabrownin. Studies have shown that theabrownin regulates intestinal flora and bile acid metabolism, resulting in increased bile acid liver production and fecal excretion, decreased liver cholesterol content, decreased fat production, and ultimately improved blood lipid and liver lipid homeostasis, thereby exerting lipid-lowering, and weight-loss effects[20]. Pu-erh tea mainly prevents obesity by inhibiting the proliferation and differentiation of adipocytes[21], regulating fat metabolism[22], improving intestinal flora[20], and regulating the expression of genes and enzymes related to lipid metabolism[23]. Catechins are a class of phenolic active substances extracted from natural plants such as tea. A large number of studies have shown that catechins have beneficial effects on reducing obesity, preventing diabetes, and improving metabolic syndrome[24,25]. Theanine is one of the abundant non-protein amino acids in tea. At present, there are few studies on the effect of theanine on obesity, and these studies are limited to animal experiments. It has been reported that L-theanine improves the metabolic characteristics of obesity by reducing liver steatosis, enhancing fat browning, and improving intestinal flora composition in HFD mice[26].

There are many reports on the effects of Pu-erh tea water extract and catechin on obesity. The research on theanine to alleviate obesity symptoms has also been involved in the field of animal experiments, but the mechanism of using the three as a composite formula to synergistically reduce lipids and for weight loss is still unclear. In addition, sourcing natural foods and functional beverages has become an important direction in obesity prevention. Theanine (TH) and catechin (CA) are new food raw materials approved by the National Health and Family Planning Commission. Therefore, the compound solid beverage obtained by combining the aqueous extract of Pu-erh tea (PT) with theanine (TH) and catechin (CA) is a natural new food functional beverage.

In this study, Pu-erh tea water extract (PT), green tea catechin (CA), and theanine (TH) were used as active ingredients to develop a Pu-erh tea composite solid beverage (PTB). C57BL/6J mice were induced by high-fat diet (HFD) to construct an obesity model. The regulation of PTB on liver lipid metabolism, intestinal barrier, and intestinal flora in HFD mice was studied, and then the mechanism of PTB alleviating obesity symptoms in HFD mice was analyzed. The purpose of this study is to provide a theoretical basis for promoting the functional application of Pu-erh tea products.

-

The water extract of Pu-erh tea (PT, extraction rate 15%), theanine (TH, purity ≥ 20%), and green tea catechin (CA, total purity 92.14%, EGCG 58.29%, ECG 19.59%, EGC 5.54%, EC 5.67%, GCG 2.17%, DL-C 0.88%) were provided by Aijia Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Changsha, Hunan, China). PTB was prepared by mixing 1.35 g PT, 400 mg TH, and 300 mg CA powder, and the additional amount of TH and CA was with reference to the 'New Food Raw Material Safety Review Management Method' (October 2023 edition).

Preparation steps of Pu-erh tea water extract were as follows: The raw materials of Pu-erh tea were crushed, and the fine powder was removed using a 10 mesh sieve. One hundred kg of crushed Pu-erh tea raw material was weighed, and 1,000 L of pure water, preheated to 90 °C, was added to the extract for 60 min. The first extraction solution was filtered through a 200-mesh sieve, and then 1,000 L of preheated pure water was added to extract for 60 min. The two extraction solutions were then combined and filtered. The extract was heated to 55~65 °C under vacuum (−0.08 to −0.095 MPa) to concentrate to a solid content of about 40%. A LPG50 centrifugal spray drying tower was used to dry the sample, and the spray powder was collected and passed through an 8-mesh sieve to obtain 14.97 kg of Pu-erh tea extract.

Animal experimental design

-

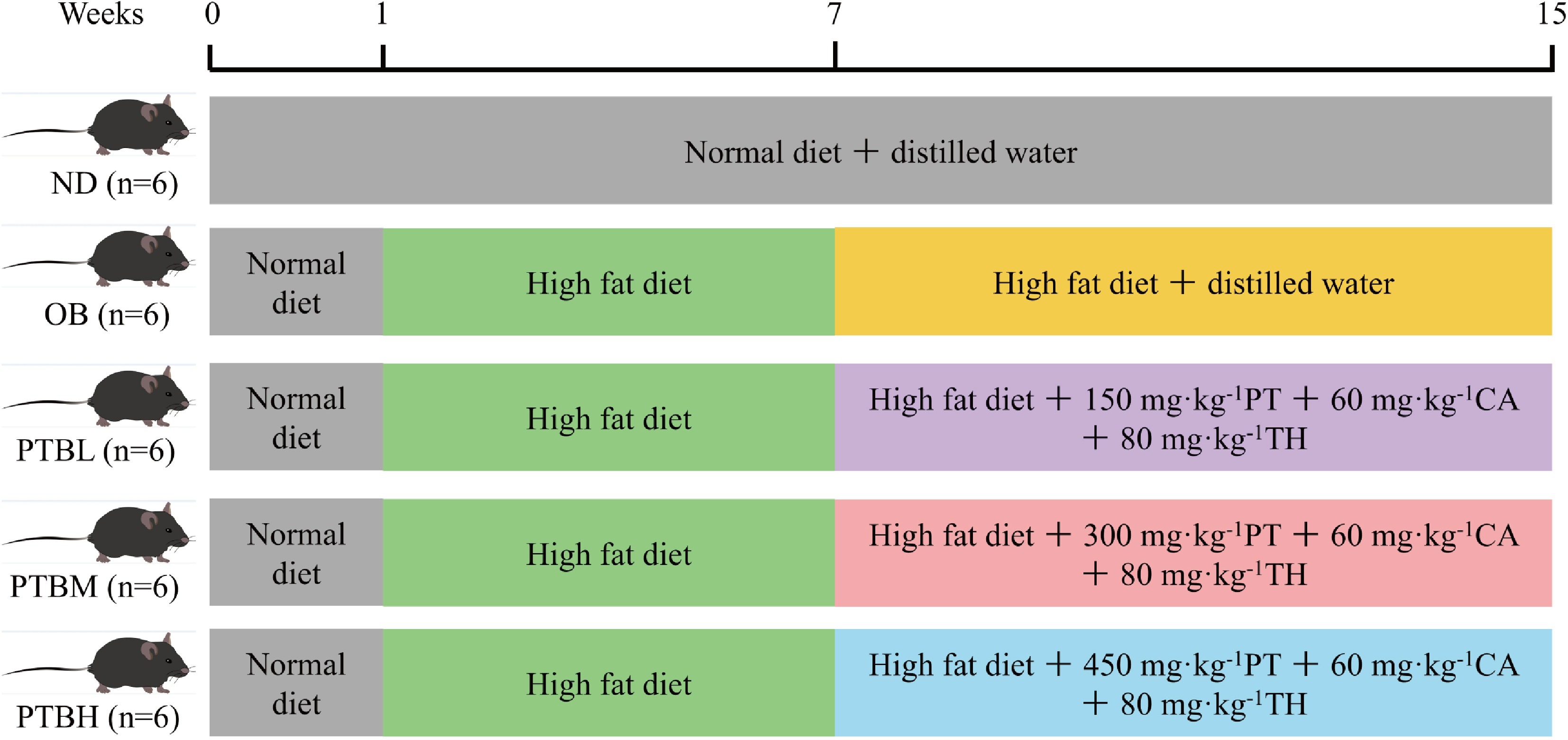

SPF male C57BL/6J mice aged 4~5 weeks were purchased from Slake Jingda Experimental Animal Co., Ltd (Changsha, Hunan, China). Production license number: SCXK 2019-0004. The temperature of the animal room was 26 °C, and the light and dark time was 12/12 h cycle. During the feeding period, the mice were free to drink and eat. The experimental design was based on the method of Yuan et al.[27]. Thirty mice were adaptively fed for one week and randomly divided into two groups. Group I was a normal diet group (ND) and fed with a control diet (n = 6). Group II was a high-fat diet group (HFD), fed with a high-fat diet (n = 24) for 6 weeks, and body weight was counted weekly. At the end of the experiment, the weight of each mouse in the HFD group was higher than the average weight of the ND group by more than 20%, and the mouse obesity model was successfully established. Normal diet (XTCON50J): protein 19.2%, carbohydrate 67.3%, fat 4.3%, calorie 3850 kcal/kg; high-fat diet (XTHF60): protein 26%, carbohydrate 26%, fat 35%, calorie 5,240 kcal/kg, purchased from Collaborative Pharmaceutical Bioengineering Co., Ltd (Nantong, Jiangsu, China).

After successful modeling, the HFD group mice were randomly divided into four groups (n = 6): obese model group (OB), low-dose Pu-erh tea beverage group (PTBL), medium-dose Pu-erh tea beverage group (PTBM), and high-dose Pu-erh tea beverage group (PTBH). The PTB group was given the corresponding dose of PTB by gavage every day (Fig. 1); the ND and OB groups were given the same amount of ultrapure water for 8 weeks, and the body weight and food intake were recorded weekly. At the end of the experiment, pentobarbital sodium (30 mg/kg) was injected intraperitoneally after fasting for 12 h. Blood, adipose tissue, liver, colon tissue, and cecal contents were collected. Some tissues were fixed with fixative, and the rest were stored in a refrigerator at −80 °C.

Figure 1.

Mouse experimental grouping diagram. ND group, normal diet group; OB group, obesity model group; PTBL group, low-dose Pu-erh tea solid beverage intervention group; PTBM group, middle dose of Pu-erh tea solid beverage intervention group; PTBH group, high-dose Pu-erh tea solid beverage intervention group; PT, Pu-erh tea extract; CA, green tea catechin; TH, theanine; n = 6.

Determination of basic indicators

-

The mice were weighed after anesthesia. When dissected, the liver and adipose tissue of the mice were weighed after washing with 4 °C normal saline, and the organ index and fat coefficient were calculated. Organ index (%) = Organ wet weight/Mouse body weight × 100.

Biochemical analysis

-

Serum samples were obtained by centrifugation (4 °C, 3,500 r/min, 10 min). Liver tissue samples were obtained by homogenization and centrifugation. The levels of total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), glutathione (GSH), malondialdehyde (MDA), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and catalase (CAT) in serum and liver were measured using a commercial kit (Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China). The levels of serum tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) were measured using Elisa kits from Huamei Biological Engineering Co., Ltd (Wuhan, Hubei, China).

Histomorphometric analysis

-

Adipose tissue, liver tissue, and colon tissue were fixed in a 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 24 h. After dehydration, embedding, and slicing, paraffin sections were made. After hematoxylin-eosin staining (H&E) and periodic acid-schiff (PAS) staining, the pathological changes of liver and adipose tissue were observed under a microscope, and the images were collected by the scanning method.

Immunofluorescence staining analysis

-

The colon paraffin sections were dewaxed into water and placed in a repair box containing ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) for antigen repair. The repaired sections were blocked with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with primary antibodies overnight. The samples were washed again with PBS, and 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was added to re-stain the nucleus. The sections after staining were sealed with an anti-fluorescence quenching sealing agent, and the final images were observed and obtained under an inverted fluorescence microscope. Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software was used to measure the cumulative fluorescence intensity value (IntDen) and the corresponding positive pixel area (Area) of the three visual fields in each slice, and the Average fluorescence intensity = Cumulative fluorescence intensity value (IntDen)/Positive pixel area (Area) was calculated.

16S rRNA gene sequencing and bioinformatics analysis

-

FastDNA Spin Kit for Soil kit was used to extract bacterial DNA from the cecal contents of mice. The V3−V4 variable region-specific primers (338F: 5'-GAGTTTGATYMTGGCTCAG-3'; 806R: 5'-GAAGGAGGTGWTCCADCC-3') were amplified by PCR and the PE amplicon library was constructed and sequenced by Illumina Miseq PE250 platform. The 16S rRNA gene sequence was classified by the ribosomal database project (RDP) classifier Bayesian algorithm. The sequences' operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were clustered according to 97% similarity. The representative sequences and relative abundance of OTUs were used to calculate Alpha diversity, including Shannon, Simpson, and other diversity indexes. Hierarchical clustering and principal component analysis (PCA) were used to evaluate Beta diversity. Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe) analysis identified potential dominant microorganisms between groups, and the effect size threshold was 4.5.

Statistical analysis

-

Image J software was used to process images. All data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and IBM SPSS Statistics 25 was used for statistical analysis. ANOVA one-way analysis of variance was first performed for data analysis among multiple groups, and then Fisher's LSD test was performed. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The graphs in this study were drawn using GraphPadPrism 8.0.1 software, Simca-P software, and TBtools software.

-

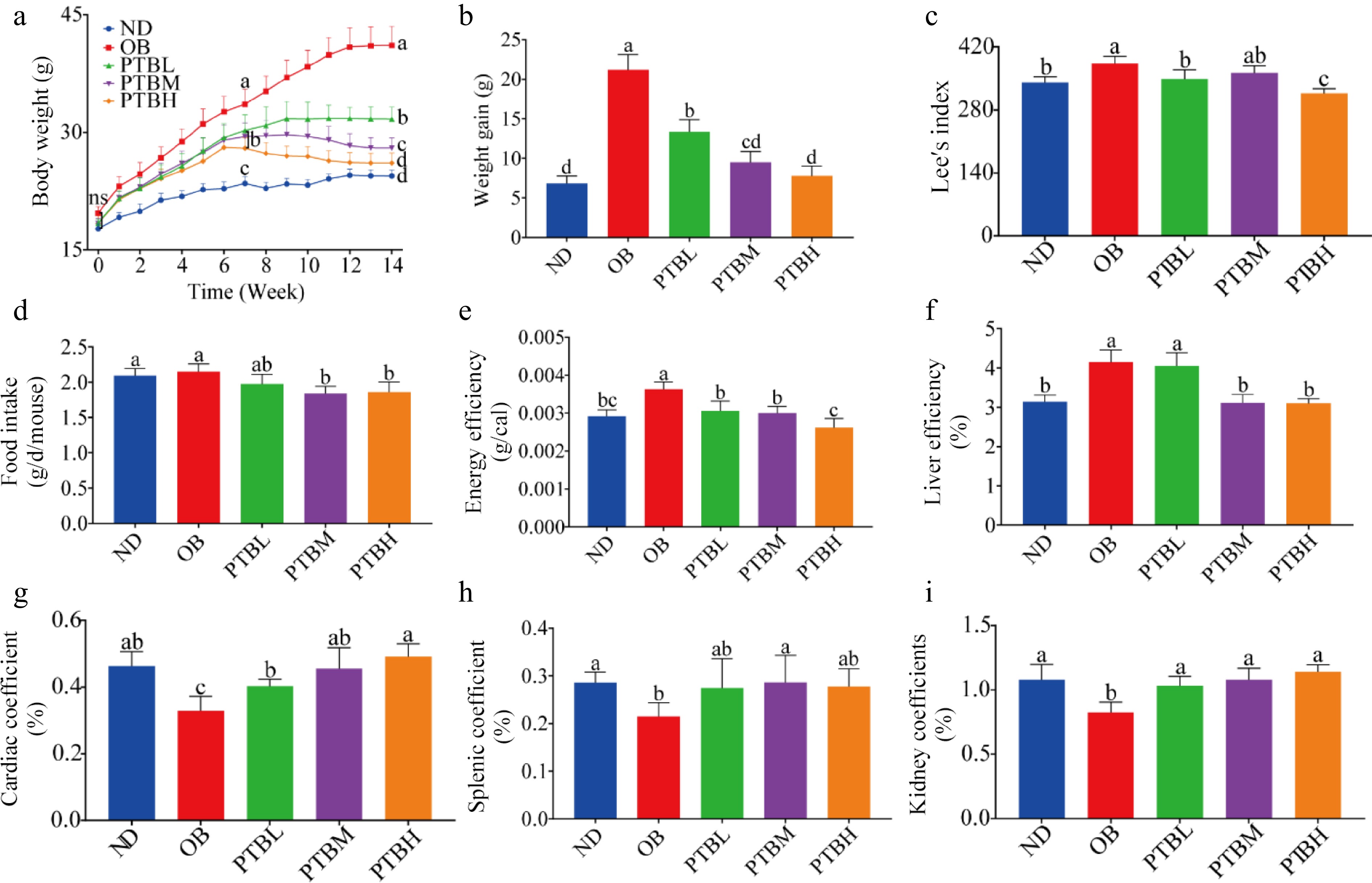

In this experiment, the effects of PTB on body weight, food intake, and organ index of HFD mice were studied. The results showed that after 6 weeks of HFD feeding, the body weight of mice increased significantly. PTB significantly inhibited the weight gain of HFD mice, and the inhibitory effect of the PTBH group was the most obvious (Fig. 2a, b). In addition, PTB significantly reduced Lee's index, food intake, and energy intake efficiency in HFD mice (Fig. 2c−e). HFD in mice may cause changes in organ weight. This study showed that PTB significantly reduced mice's liver coefficient and increased mice's heart, spleen, and kidney coefficients (Fig. 2f−i). The above results indicate that PTB can inhibit body weight gain and liver enlargement in HFD mice.

Figure 2.

Effects of PTB on body weight, food intake, and organ index of high-fat diet mice. ND group, normal diet group; OB group, obesity model group; PTBL group, low-dose Pu-erh tea solid beverage intervention group; PTBM group, middle dose of Pu-erh tea solid beverage intervention group; PTBH group, high-dose Pu-erh tea solid beverage intervention group. (a) Changes in body weight of mice; (b) Weight gain of mice; (c) Lee's index; (d) Food intake; (e) Energy efficiency; (f) Liver coefficient; (g) Cardiac coefficient; (h) Spleen coefficient; (i) Kidney coefficient.

Effects of PTB on serum biochemical indexes in mice fed with a high-fat diet

-

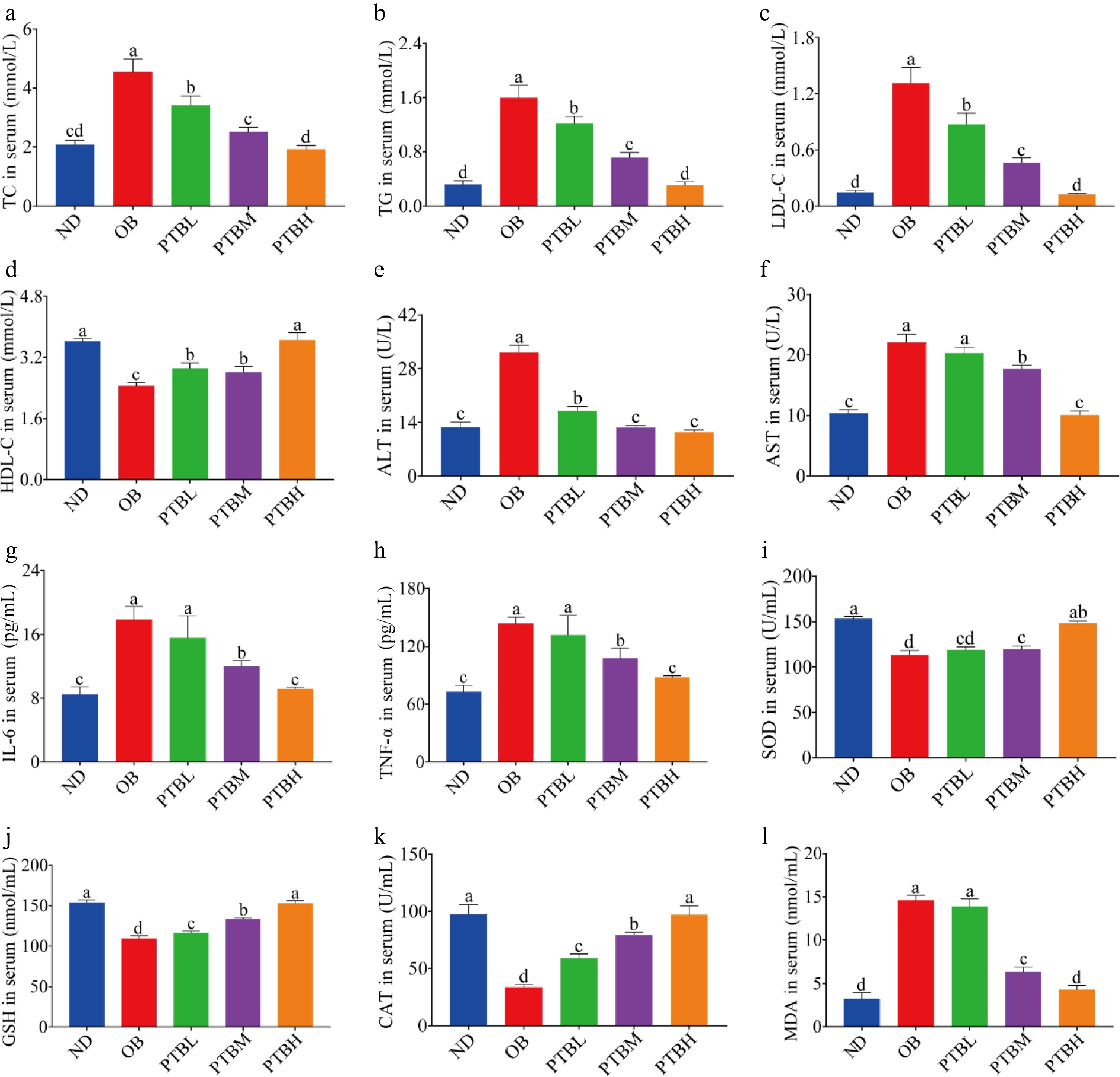

Hyperlipidemia is a common complication of obesity, often manifested as elevated triglyceride, total cholesterol, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, while high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels decrease. Compared with the ND group, the levels of TG, TC, and LDL-C in the serum of the OB group were significantly increased. HDL-C levels were significantly reduced, while PTB intervention significantly alleviated this trend, and PTBH had the best mitigation effect (Fig. 3a−d). It shows that PTB can effectively improve dyslipidemia in HFD mice. Studies have shown that obesity may cause impaired liver function, which is manifested by increased transaminase activity. In addition, the detection of liver function evaluation indicators in mice was found. In addition, the liver function evaluation index of mice was detected. Compared with the OB group, the levels of ALT and AST in the serum of mice in the PTBM group and the PTBH group were significantly lower (Fig. 3e, f), indicating that PTB effectively repaired the liver damage of HFD mice.

Figure 3.

Effects of PTB on serum biochemical indexes in mice fed with a high-fat diet. ND group, normal diet group; OB group, obesity model group; PTBL group, low-dose Pu-erh tea solid beverage intervention group; PTBM group, middle dose of Pu-erh tea solid beverage intervention group; PTBH group, high-dose Pu-erh tea solid beverage intervention group. TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; GSH, glutathione; MDA, malondialdehyde; SOD, superoxide dismutase; CAT, catalase. (a)−(d) the level of TC, TG, LDL-C, HDL-C in serum; (e), (f) serum ALT, AST activity; (g), (h) the level of IL-6 and TNF-α in serum; (i)−(l) Serum SOD, GSH, CAT, MDA concentrations.

The anti-inflammatory effect of PTB on HFD mice was evaluated by detecting the release levels of inflammatory factors interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) in serum. The results showed that PTB significantly reduced the release levels of IL-6 and TNF-α in the serum of mice (Fig. 3g, h), indicating that PTB has a good anti-inflammatory effect. In addition, PTB increased the oxidative stress ability of HFD mice. After PTB treatment, the activities of SOD, GSH, and CAT in the serum of mice were significantly increased, and the activity of MDA was significantly decreased (Fig. 3i−l).

Effects of PTB on liver morphology, lipid level, and oxidative stress in mice fed with a high-fat diet

-

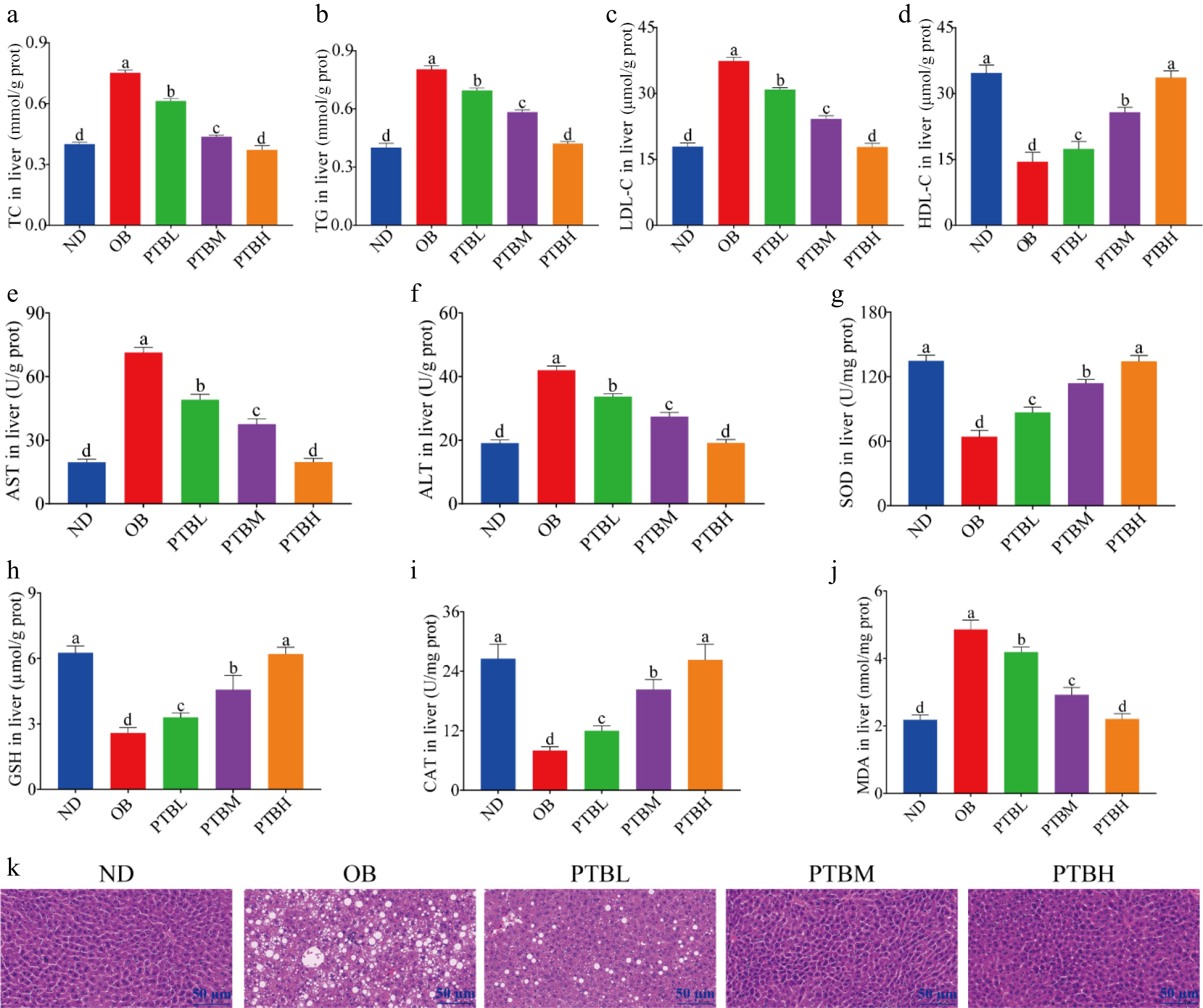

Obesity usually leads to lipid accumulation in the liver and impaired liver function, accompanied by specific forms of steatosis and liver inflammation. In this study, the levels of blood lipid, liver function, and oxidative stress in the liver of mice were detected. The results were consistent with those in the serum. PTB alleviated dyslipidemia (Fig. 4a−d) and impaired liver function (Fig. 4e, f) in HFD mice, and improved the oxidative stress ability of the liver in mice (Fig. 4g, h). Moreover, PTBH has the best effect, which can restore the obesity indexes of mice to normal levels. H&E staining analysis of mouse liver tissue showed that the liver morphology of mice in the OB group was abnormal, a large number of lipid droplets vacuoles appeared, irregular arrangement, hepatic lobule structure was damaged, and lipid accumulation was serious. PTB intervention alleviated HFD-induced fat vesicle accumulation, liver structure damage, and fat accumulation, showing a clear liver tissue structure (Fig. 4k).

Figure 4.

Effects of PTB on liver morphology, lipid level, and oxidative stress in mice fed a high-fat diet. ND group, normal diet group; OB group, obesity model group; PTBL group, low-dose Pu-erh tea solid beverage intervention group; PTBM group, middle dose of Pu-erh tea solid beverage intervention group; PTBH group, high-dose Pu-erh tea solid beverage intervention group. TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; GSH, glutathione; MDA, malondialdehyde; SOD, superoxide dismutase; CAT, catalase. (a)−(d) Liver TC, TG, LDL-C, HDL-C concentration; (e), (f) the activity of ALT and AST in the liver; (g)−(j) the concentration of SOD, GSH, CAT, MDA in the liver; (k) Liver H&E staining sections (scale bar = 50 μm).

Effects of PTB on adipose tissue morphology, fat weight, and adipocyte size in high-fat diet mice

-

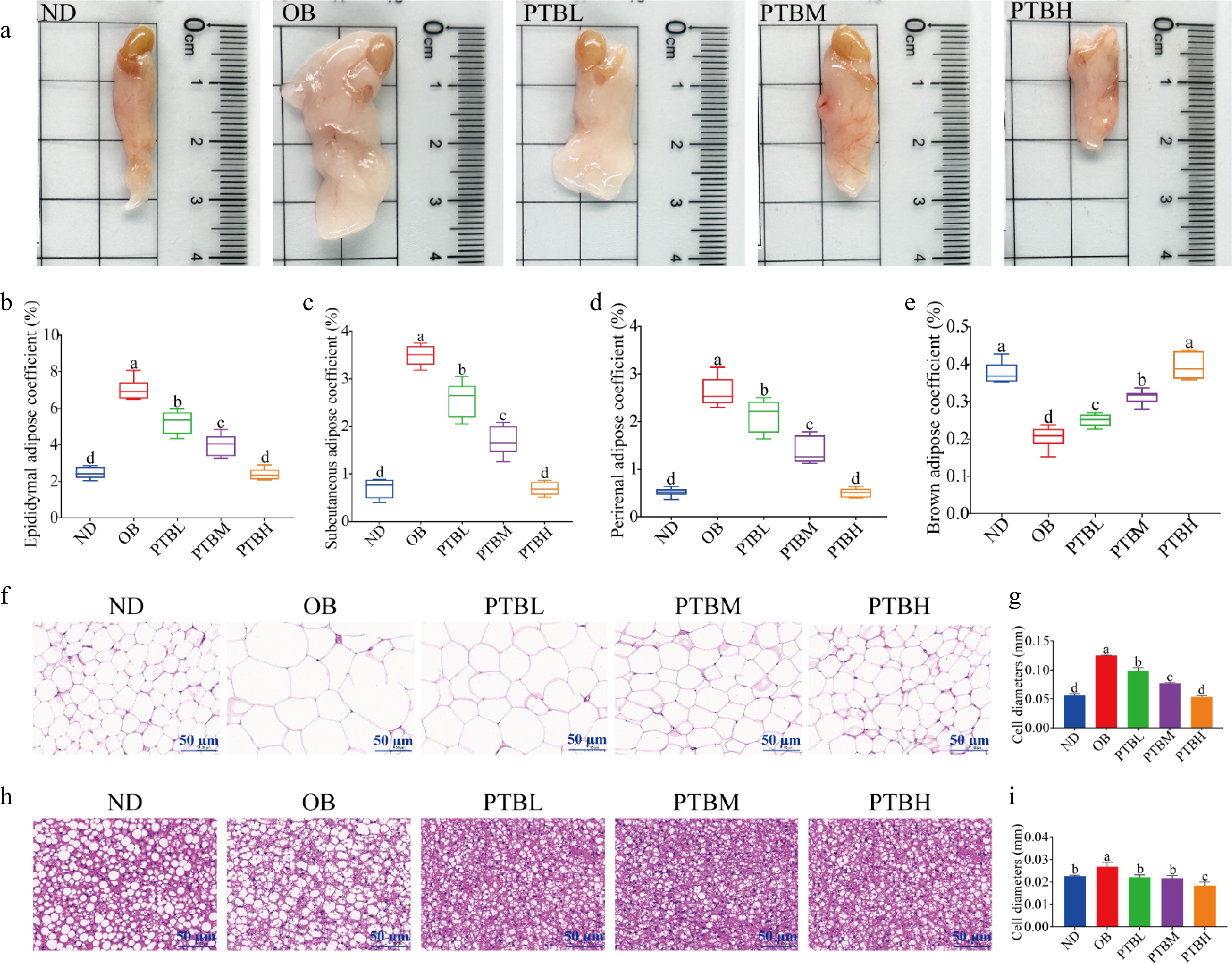

The increase in body weight in obese mice is related to fat weight and adipocyte size. It can be seen from Fig. 5a that the epididymal adipose tissue of mice in the OB group was significantly larger than that in the ND group, and the epididymal adipose tissue of mice became smaller after PTB intervention, indicating that PTB could inhibit the growth of epididymal adipose tissue in mice, and the inhibitory effect of PTBH group was the most obvious. In addition, PTB intervention significantly reduced the weight of epididymal fat, inguinal fat, and perirenal fat in mice, and increased the weight of brown fat (Fig. 5b−e), indicating that PTB can inhibit the increase of white fat weight in mice, thereby inhibiting the weight gain of mice. To explore the effect of PTB on the morphology of adipose tissue in mice, H&E staining was performed on the adipose tissue of mice. The results showed that the area of a single adipocyte in the OB group was significantly larger than that in the ND group, and the arrangement of cells was disordered. After PTB intervention, the area of single cells in adipose tissue became smaller, the fat expansion was improved, and the cell arrangement tended to be neat (Fig. 5f−i). The above results indicate that PTB can effectively inhibit HFD-induced fat accumulation in mice.

Figure 5.

Effects of PTB on adipose tissue morphology, fat weight, and adipocyte size in high-fat diet mice. ND group, normal diet group; OB group, obesity model group; PTBL group, low-dose Pu-erh tea solid beverage intervention group; PTBM group, middle dose of Pu-erh tea solid beverage intervention group; PTBH group, high-dose Pu-erh tea solid beverage intervention group. (a) Photos of epididymal fat in mice; (b) Epididymal fat coefficient; (c) Groin fat coefficient; (d) Perirenal fat coefficient; (e) Brown fat coefficient; (f) H&E staining sections of epididymal adipose tissue (scale bar = 50 μm); (g) Epididymal adipocyte diameter; (h) H&E staining sections of brown adipose tissue (scale bar = 50 μm); (i) Brown adipocyte diameter.

Effects of PTB on colon injury and colonic intestinal barrier function in mice fed with a high-fat diet

-

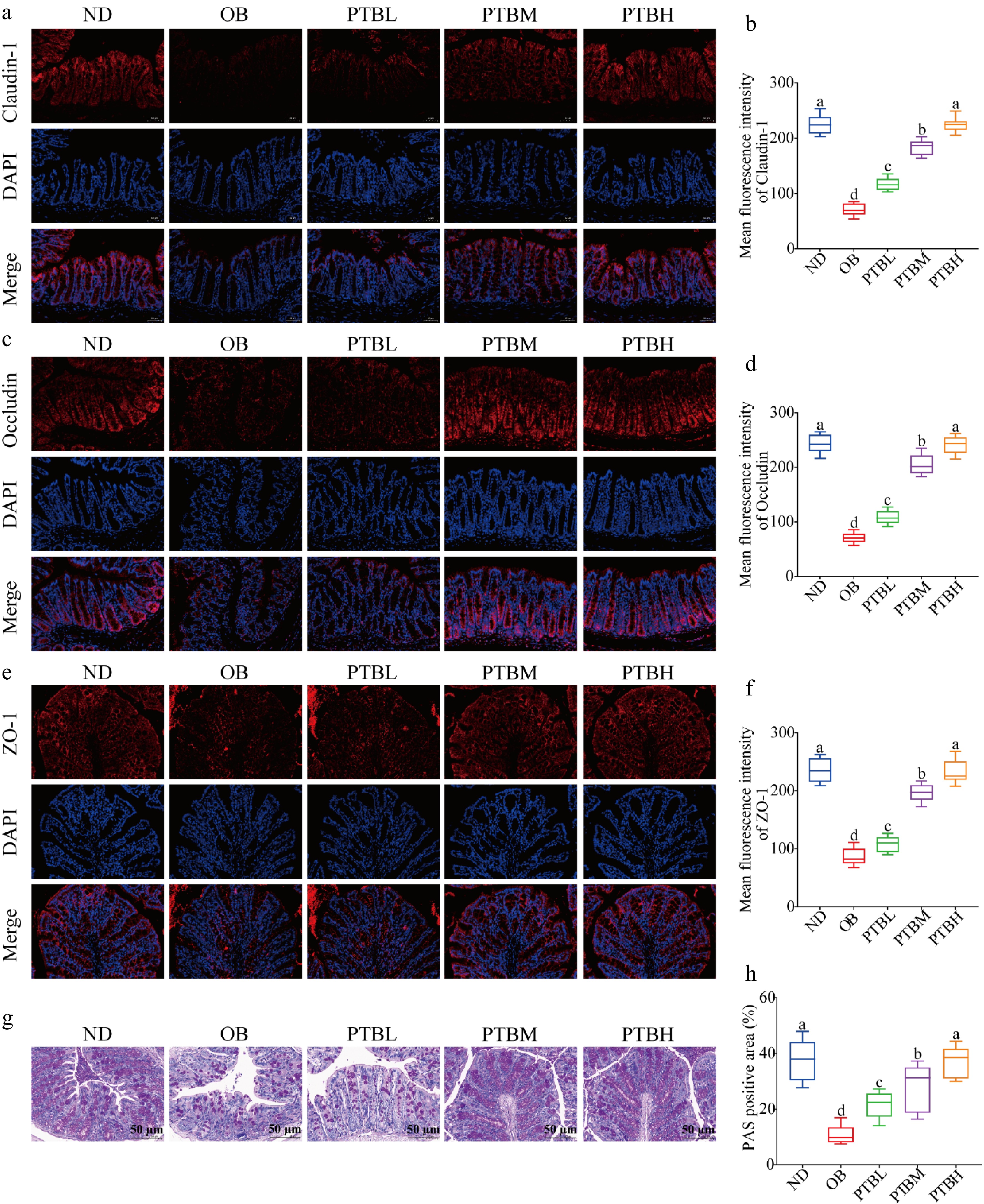

A long-term high-fat diet can cause colon damage in mice, especially since the physical barrier of the colon will be destroyed. In this study, the expression of colonic tight junction proteins Claudin-1, Occludin and ZO-1 were detected by immunofluorescence technique to evaluate the integrity of the colonic intestinal barrier. The results showed that PTB could significantly increase the expression levels of Claudin-1, Occludin, and ZO-1 in the colon of mice, indicating that PTB had a protective effect on the intestinal barrier of HFD mice (Fig. 6a−f). In addition, PAS staining analysis of colon tissue showed that compared with the ND group, the colon intestinal tract of mice in the OB group was disordered, the villi were incomplete, the edema between the mucosal layer and the muscular layer was obvious, the inflammatory infiltration was serious, and the goblet cells were unevenly distributed and the number was small. After PTB treatment intervention, edema, and inflammatory infiltration were significantly improved, and the number of goblet cells was restored (Fig. 6g, h). In conclusion, PTB can effectively improve the impaired intestinal barrier function of the colon in HFD mice, thereby reducing colon injury.

Figure 6.

Effects of PTB on colon injury and intestinal barrier function in mice fed with a high-fat diet. Claudin-1, occludin, and ZO-1 immunofluorescence staining results and average fluorescence intensity (scale bar = 50 μm) in colon tissue of (a)−(f) mice; (g) PAS staining results of colon tissue (scale bar = 50 μm); (h) PAS-positive staining area. ND group, normal diet group; OB group, obesity model group; PTBL group, low-dose Pu-erh tea solid beverage intervention group; PTBM group, middle dose of Pu-erh tea solid beverage intervention group; PTBH group, high-dose Pu-erh tea solid beverage intervention group.

Regulatory effect of PTB on intestinal flora in high-fat diet mice

-

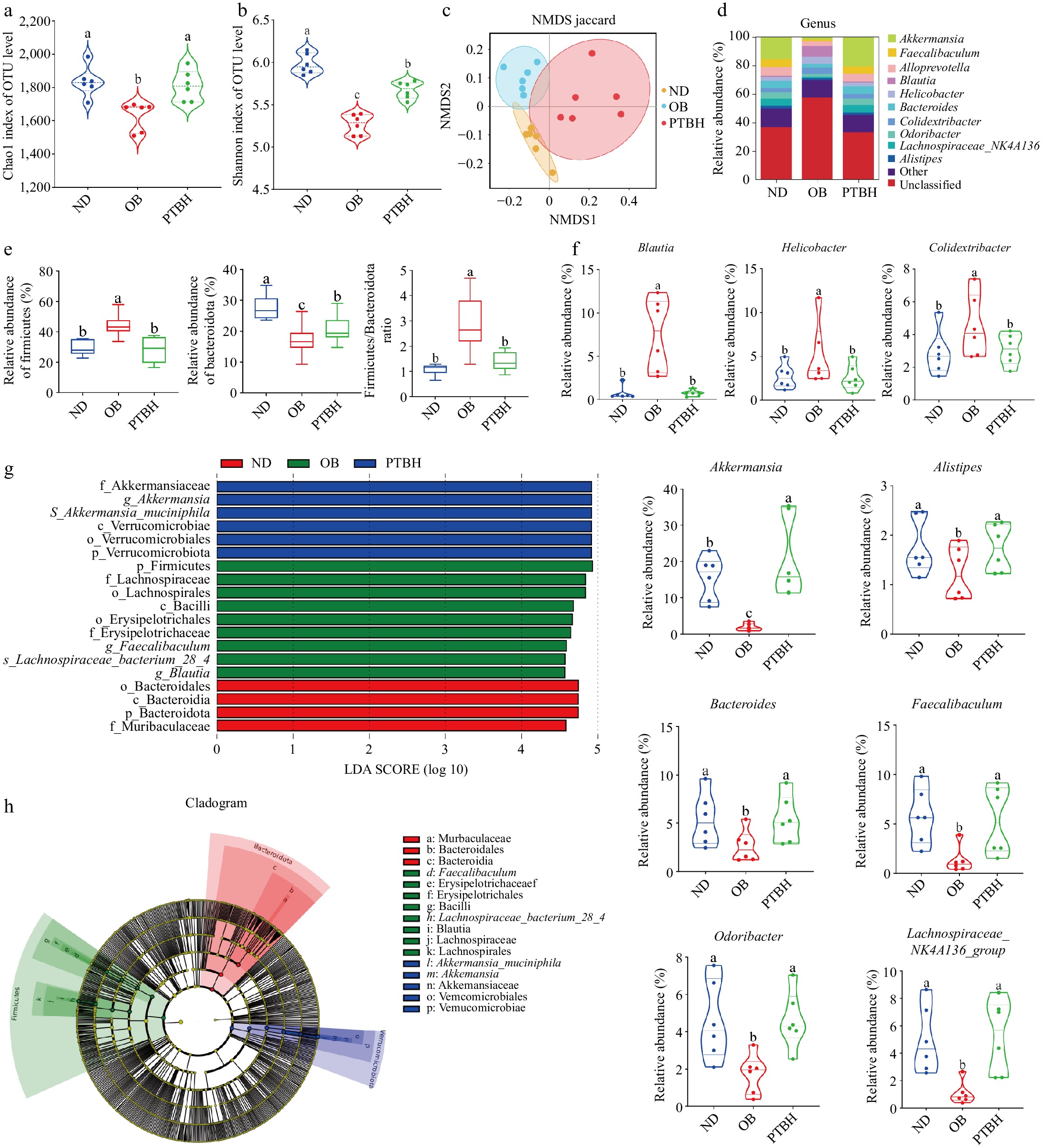

Based on the above experimental results, we found that the PTBH group had the best lipid-lowering effect. To further study the mechanism of PTB alleviating obesity in HFD mice, 16S rRNA sequencing analysis was performed on the cecal contents of the ND group, OB group, and PTBH group. The diversity of intestinal flora in mice was analyzed by the alpha diversity index (Chao1 index and Shannon index). As shown in Fig. 7a, b, PTB significantly increased the Chao1 index and Shannon index of the intestinal tract of HFD mice, indicating that PTB could improve the uniformity and complexity of the intestinal microbial community in mice. The beta diversity of intestinal flora was evaluated by a non-metric multidimensional scale (NMDS) score plot. The results showed that the samples in each group were significantly separated, indicating that there were significant differences in the composition of intestinal microorganisms in each group (Fig. 7c).

Figure 7.

The regulatory effect of PTB on intestinal flora in high-fat diet mice. (a) Chao1 index; (b) Shannon index; (c) Non-metric multidimensional scale (NMDS) score plot; (d) Species composition distribution map at genus level; (e) The abundance and ratio of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes; (f) Represents the relative abundance of the genus; (g) LDA score of LEfSe analysis; (h) Phylogenetic tree of LEfSe analysis. ND group, normal diet group; OB group, obesity model group; PTBH group, high-dose Pu-erh tea solid beverage intervention group.

Analysis of species composition at the phylum and genus levels found that at the phylum level, the intestinal flora of mice was mainly composed of Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Verrucomicrobiota, Proteobacteria, and so on. PTB significantly reduced Firmicutes abundance and F/B ratio, and increased Bacteroidetes abundance (Fig. 7e). At the genus level, PTB significantly reduced the abundance of Blautia, Helicobacter, and Colidextribacter, indicating that these bacteria may be harmful to obesity in mice. The abundance of Akkermansia, Alistipes, Bacteroides, Faecalibacterium, Odoribacter, and Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group was increased, indicating that these genera were beneficial to alleviate obesity in mice (Fig. 7f).

To identify species with significant differences between groups, we performed LEfSe analysis (LDA > 4.5) to determine specific dominant bacterial phenotypes (Fig. 7g, h), and 19 taxa were identified as key discriminant factors. The results showed that Lachnospiraceae_bacterium_28_4 species were significantly enriched in the OB group; Akkermansia_muciniphila was significantly enriched in the PTBH group.

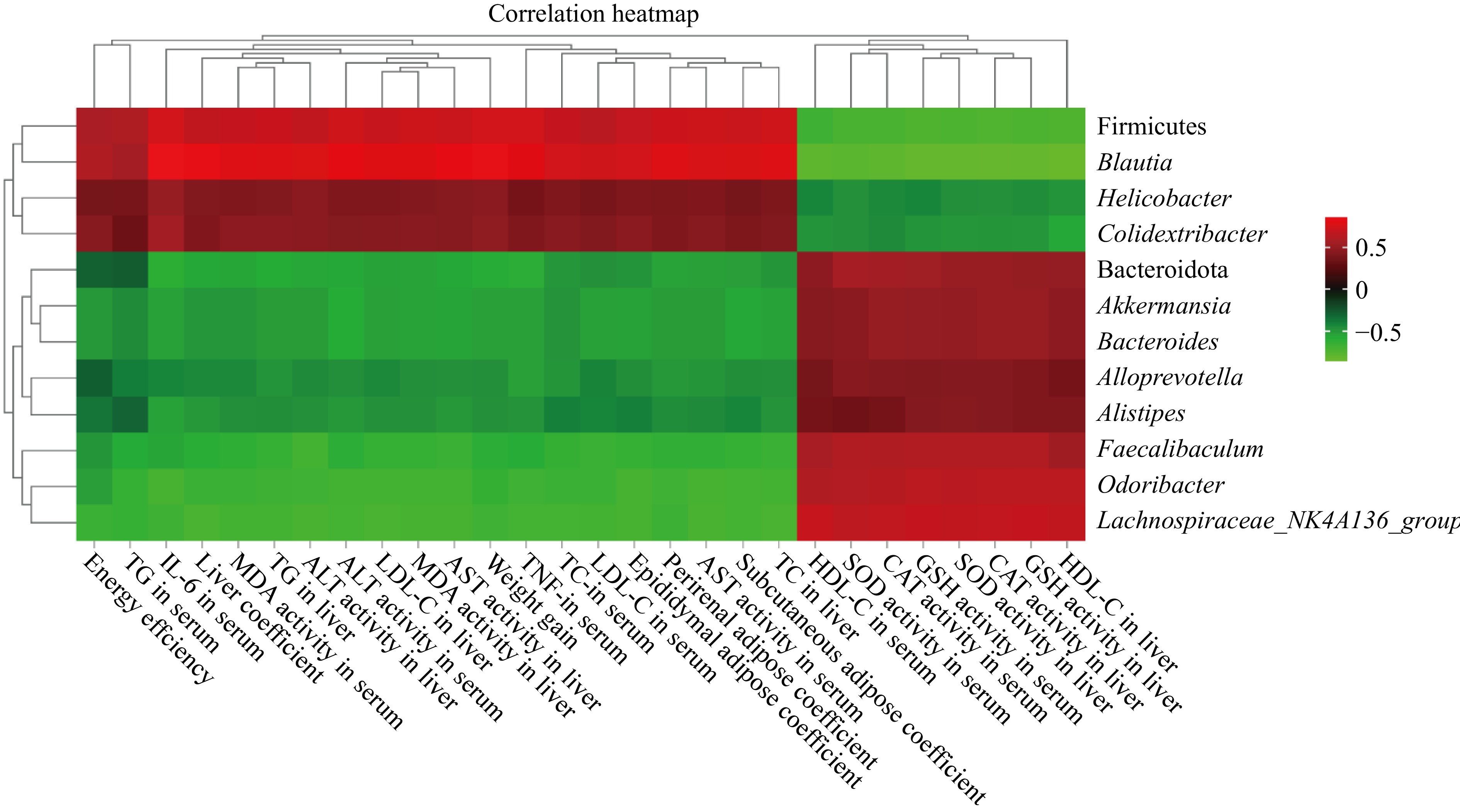

Pearson correlation analysis was performed on the abundance of dominant bacteria and obesity-related parameters (Fig. 8). The results showed that body weight gain, energy efficiency, liver index, white fat weight, serum and liver TC, TG, LDL-C, ALT, AST, TNF-α, IL-6, and MDA content were positively correlated with Firmicutes, Blautia, Helicobacter, and Colidextribacter abundance. It was negatively correlated with the abundance of Bacteroidetes, Akkermansia, Alistipes, Bacteroides, Faecalibacterium, Odoribacter, and Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group.

-

This study explored the regulatory effects of PTB on dyslipidemia, liver function impairment, fat accumulation, colon injury, and intestinal flora disorder in HFD mice, to elucidate the mechanism of PTB alleviating obesity in HFD mice mediated by intestinal flora.

The liver is recognized as the center of glucose and lipid metabolism. Excessive lipid intake and lipid oxidative stress damage to the liver are the main causes of fatty liver disease caused by a high-fat diet[28]. In this study, HFD caused systemic chronic inflammation and excessive oxidative stress in mice, resulting in impaired normal liver function, and the expression levels of AST and ALT in the liver of mice were significantly reduced. The intervention of PTB effectively reduced the inflammatory state induced by high-fat diet, improved the level of oxidative stress in the whole body, and played a significant protective role in liver function, indicating that PTB could improve the metabolic capacity of the body under high-fat conditions by protecting the normal function of the important glycolipid metabolic organ-liver. Therefore, we speculate that the lipid-lowering and weight-reducing effects of PTB are inseparable from its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects in its inclusions. In addition, PTB intervention significantly increased the weight of brown adipose tissue in HFD mice. It has been reported that brown adipose tissue can secrete adipokines and microvesicles, and target peripheral tissues such as the liver and skeletal muscle to communicate with remote organs to regulate lipid metabolism and reduce lipid synthesis and storage[29]. Therefore, we speculate that another important mechanism of PTB's lipid-lowering and weight loss is that it may exert the lipid-burning effect of brown fat by slowing down lipid deposition so that different adipose tissues can function normally.

This study also showed that PTB had an improved effect on intestinal health imbalance caused by a high-fat diet. The mechanical barrier is the most important protective barrier among the four major intestinal barriers, which can prevent harmful microorganisms and their metabolites from entering the blood circulation[30]. PTB promoted the expression of intestinal tight junction proteins Claudin-1, Occludin, and ZO-1, and prevented the imbalance of intestinal flora caused by a high-fat diet from affecting the host from the mechanical barrier level. In addition, PTB has a significant effect on improving the intestinal biological barrier of HFD mice, which significantly down-regulates the F/B value in the intestine of HFD mice. Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes are the two main intestinal flora that affect energy metabolism homeostasis[31]. Indicating that PTB alleviates the imbalance of energy homeostasis in mice by regulating the abundance of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes in the intestine of HFD mice to inhibit obesity symptoms. Moreover, PTB significantly increased the abundance of beneficial bacteria Akkermansia, Faecalibacterium, Odoribacter, and Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group in the intestine of mice, reduced the growth of harmful bacteria Blautia, Helicobacter, and Colidextribacter in obese mice, and affected the quorum sensing between the intestines. Studies have reported that Akkermansia is positively correlated with the ability to enhance the intestinal barrier and protect the host from metabolic inflammation[32], which further indicates that the weight loss effect of PTB may be achieved by alleviating chronic inflammation of the body. In addition, Pearson correlation analysis showed that the abundance of these beneficial bacteria was negatively correlated with obesity indicators such as body weight gain and adipose tissue weight in mice, indicating that PTB alleviated obesity in HFD mice by increasing the abundance of these beneficial bacteria in the intestine of mice. In conclusion, PTB plays a beneficial role in weight loss in HFD mice by protecting the intestinal mechanical barrier and microbial barrier in HFD mice to maintain the balance of intestinal homeostasis and improve intestinal health.

In this study, CA and theanine were added to PT, so the lipid-lowering and weight-loss of PTB were the result of the synergistic effect of PT, CA, and theanine. However, the role of PT, CA, and theanine in the lipid-lowering and weight-loss process of PTB was unknown. Further in-depth study is expected to improve the formula ratio of Pu-erh tea solid beverage, such as increasing the separate CA and theanine treatment group for comparison, to further explore the lipid-lowering and weight-loss mechanism of PTB.

-

In summary, our study found that PTB alleviated obesity symptoms in high-fat diet mice by regulating lipid deposition and intestinal flora disorders, and its improvement effect was dose-dependent. These findings provide a theoretical reference for the anti-obesity mechanism of Pu-erh tea solid beverages and have reference value for the development of tea efficacy-based solid beverages.

This work was supported in part by the National Key R&D Project (2022YFE0111200), the Key R&D Project of Hunan Province (2021NK1020-3) and the Key R&D Project of Yunnan Province (202202AE090030).

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Li J, Liu A, Zhang S, Zhou Y; material preparation and data collection: Li J, Zhang S; data analysis: Li J, Liu A; draft manuscript preparation and revision: Li J, Tang Y, Liu A, Zhang S; partial funds and consultation: Zhang S, Liu Z. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Li J, Zhou Y, Tang Y, Liu Z, Zhang S, et al. 2025. Effect of Pu-erh tea compound solid beverage on weight loss of high-fat diet mice. Beverage Plant Research 5: e014 doi: 10.48130/bpr-0025-0011

Effect of Pu-erh tea compound solid beverage on weight loss of high-fat diet mice

- Received: 28 December 2024

- Revised: 20 February 2025

- Accepted: 19 March 2025

- Published online: 20 May 2025

Abstract: Obesity is prevalent worldwide and seriously affects human health. At present, there are many reports on the lipid-lowering and weight loss effect of Pu-erh tea water extract, catechin, and theanine, but there are few studies on the synergistic lipid-lowering and weight loss of the three as a combined formula. The purpose of this study was to explore the anti-obesity effect of Pu-erh tea compound solid beverage composed of Pu-erh tea water extract, catechin, and theanine on high-fat diet mice. In this study, C57BL/6J mice were induced using a high-fat diet to construct an obesity model, and Pu-erh tea solid beverage was given by intragastric intervention. After 8 weeks of intragastric administration, the body weight, serum TG, TC, LDL-C, and liver TG and TC levels in the solid beverage intervention group were significantly decreased. The expression levels of tight junction proteins ZO-1, Occludin, and Claudin-1 in colon tissue were significantly increased. 16S rRNA analysis showed that Pu-erh tea solid beverage delayed the increase of Blautia, Helicobacter, Colidextribacter abundance, and the decrease of Akkermansia, Bacteroides, Alistipes, Faecalibaculum, Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group, Odoribacter abundance caused by a high-fat diet, and increased the species abundance of the intestinal microbial community. The above results showed that Pu-erh tea solid beverage could inhibit obesity in high-fat diet mice by alleviating dyslipidemia, intestinal barrier damage, and intestinal flora disorders in high-fat diet-fed mice.

-

Key words:

- Pu-erh tea solid beverage /

- Obesity /

- High-fat diet /

- Lipid abnormality /

- Intestinal barrier /

- Intestinal flora