-

Hydrocarbon fuels such as gasoline and diesel are the core energy carriers of the modern energy system and are indispensable for energy conversion and utilization. Substantial soot emissions are predominantly generated during the incomplete combustion of hydrocarbons, which poses a major threat to air quality[1,2], and human health[3,4]. Soot particles can cause nozzle clogging and engine damage, thereby reducing combustion efficiency. In addition, in terms of climate warming impact, soot particles rank as the second major contributor after carbon dioxide. Studies have shown that polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are critical soot precursors, and their formation and growth mechanisms govern soot particle formation. Therefore, exploring PAHs formation mechanisms in flames is conducive to the development of cleaner combustion equipment, thereby reducing the production of soot, to achieve the control of soot emissions.

Given the complexity of PAH formation, several mechanisms have been proposed over the decades to explain their growth from small hydrocarbons[5−19]. The hydrogen-abstraction-acetylene-addition (HACA) mechanism is the most widely used, most mature, and widely recognized mechanism among all mechanisms for PAH formation, but its validity in some cases has been questioned. For example, previous studies have shown that the stepwise addition of acetylene based on this mechanism is slow to reproduce experimentally observed concentrations of PAHs[10,20]. In addition, this mechanism alone is insufficient to explain the generation of larger aromatic molecules, such as the growth from naphthalene to phenanthrene or anthracene[21]. A previous experimental study has shown that naphthalene can be formed via the phenyl/vinylacetylene reaction under low-temperature conditions. Therefore, researchers then proposed a hydrogen-abstraction-vinylacetylene-addition (HAVA) mechanism to explain the generation of PAHs in low-temperature environments. Despite this, the ring growth rate through the stepwise addition of acetylene or vinylacetylene is still slow, making it difficult to explain the rapid generation of soot through these mechanisms. Thus, the reaction pathways leading to soot formation still needs further study.

Phenylacetylene is the simplest aromatic alkynyl and is a potential precursor for PAHs and eventually soot formation[22]. Studies show that the concentration of phenylacetylene can be high in alkylbenzene flames and premixed ethylene soot flames[23,24]. Based on this point, Jin and Ye, two of our authors together with their co-workers proposed the hydrogen abstraction phenylacetylene addition (HAPaA) mechanism[25]. The potential contribution of this mechanism in PAHs formation and growth has been revealed by combined theoretical and experimental investigations of the reactions of phenyl[26], 1-naphthyl[25], and 4-phenanthryl[25] radicals with phenylacetylene.

Naphthalene, the simplest bicyclic aromatic hydrocarbon, is not only a component of crude oil, but can also be found in petroleum derived fuels (such as diesel, and aviation kerosene)[27,28]. As a key soot precursor, previous investigations have shown that abstracting hydrogen from naphthalene produces nearly equal amounts of 1- and 2-naphthyl radicals, the chemical kinetics of which have been previously investigated[29−32]. Previous research on naphthyl radicals mainly focuses on its interaction with small molecules such as acetylene (C2H2) and ethylene (C2H4)[33−36], while the reaction with larger aromatics such as phenylacetylene is relatively scarce. Consequently, we focus our attention on the addition reactions between naphthyl radicals and phenylacetylene. Since the reaction between 1-naphthyl and phenylacetylene has been studied in our earlier work, in this study we choose to investigate the reaction between 2-naphthyl and phenylacetylene for a better understanding of the novel HAPaA mechanism.

In this work, the reaction products of 2-naphthyl and phenylacetylene were experimentally investigated in a flow reactor at 5 Torr, at temperatures of 698 and 1,248 K. To determine the structures and composition of products, the collected molecular beam of products was detected and analyzed using the reflectron time-of-flight mass spectrometer (RTOF-MS). Based on the experimental detections, we employed electronic structure computations combining hybrid density function theory (DFT) and double-hybrid DFT methods to explore the potential pathways of the 2-naphthyl + phenylacetylene reaction. Rate constants were obtained by performing RRKM/master equation simulations with the MESS code, by utilizing the chemically significant eigenvalue (CSE) approach. Coupling the experimental and theoretical results, we analyzed the formation of significant products and the competitive relationships of reaction pathways.

-

The undulator-based Synchrotron Vacuum Ultraviolet (SVUV) beamline (BL03U) at Hefei Light Source II (China) was employed for the experiments[37,38]. A pyrolysis experimental setup was used to investigate the reaction between 2-naphthyl and phenylacetylene. A full description of the experimental setup has been provided elsewhere[38]. The experimental setup includes a resistively heated flow reactor and a supersonic molecular beam sampling apparatus coupled to the reflectron time-of-flight mass spectrometer (RTOF-MS). The resistively heated flow reactor was employed to simulate combustion-relevant conditions for studying polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) formation via the radical-molecule reactions of 2-naphthyl with phenylacetylene. The reactor system comprised a home-made furnace and an α-type alumina ceramic tube (7.0 mm inner diameter, 1.5 mm wall thickness), with a total heating zone length of 220 mm. A tungsten–rhenium (W–Re) thermocouple was positioned at the center of the heating zone to precisely control the reacting temperature.

The pyrolysis of 2-bromonaphthalene (Macklin, 98%) generated 2-naphthyl radicals in situ, which were then mixed with phenylacetylene (Sigma-Aldrich, 98%) with argon as the carrier gas at 5 Torr. The supersonic molecular beam was formed by extracting reaction products through a quartz nozzle, driven by the significant pressure gradient between the reactor and downstream vacuum chambers. After passing through the skimmer, the molecular beam entered the RTOF-MS system. The tunable SVUV light from the synchrotron beamline ionized species, and ions were then analyzed by the SVUV photoionization molecular beam mass spectrometry (SVUV-PI-MBMS).

Quantum chemistry methods

-

To elucidate the chemical kinetics of the reaction between 2-naphthyl radicals and phenylacetylene, we computationally determined the potential-energy profiles for reaction pathways originating from the six distinct addition sites on phenylacetylene. Given the large size of species with as many as 18 carbon atoms, wavefunction-based high-level post-Hartree-Fock methods like CCSD(T) are computationally prohibitive. Therefore, we employed a balanced approach to achieve reliable results within reasonable computational cost. Geometry optimization and vibrational frequency calculations of all stationary points on the potential-energy profiles were performed at the M06-2X/6-311+G(d,p) level of theory[39] with Grimme's D3 dispersion correction[40]. All transition states were confirmed by the presence of a single imaginary frequency, and the corresponding vibrational modes were visualized using Gaussview 6.0 to verify proper connectivity between designated reactants and products. To further reduce the computational errors, the zero-point energies were corrected with a scaling factor of 0.97[41]. The B2PLYP-D3/def2-TZVPP[42,43] method was used to obtain more accurate single-point energies. To test the accuracy of the current energy scheme, calculations of standard enthalpies of formation were performed against both experimental and high-level theoretical data for representative unsaturated hydrocarbons. The calculated results provide confidence for the accuracy of our computational approach for this reaction system (see Supplementary Table S1).

All electronic structure computations were performed with the Gaussian 16 program[44].

Reaction kinetics

-

RRKM/ME calculations were performed with the MESS code[45,46] to determine temperature- and pressure-dependent rate coefficients (500–2,500 K and 3–7,600 Torr). The single-exponential down model was applied to describe the collisional energy transfer and the average energy transferred per collision in a downward direction is assumed to have the form of <ΔEdown> = 400 (T/300 K)0.8[25]. Additionally, the collision frequencies between reactants and bath gas were estimated by assuming the Lennard-Jones potential model, with the parameters of (ε, σ) = (476.4 cm−1, 7.936 Å)[47] for the complexes and (ε, σ) = (79.2 cm−1, 3.47 Å)[48] for argon.

Considering the low barrier for the initial addition step where 2-naphthyl radicals attack phenylacetylene at its β-carbon, the variational effect was considered in our rate constant calculations by using the variational transition state theory (VTST)[49,50]. The minimum energy pathway (MEP) in the vicinity of the transition state structures was calculated by performing a relaxed scan. For the configurations along the MEP, the frequencies and single-point energies were computed using the same energy scheme as described in above section "Quantum chemistry methods". The projection of harmonic frequencies of the MEP configurations was done in Cartesian coordinates. During the implementation of VTST, the transition state was varied at different positions along the MEP, where the configuration with a minimal sum of states at every given energy was designated as the optimal transition state. In particular, the minimization of rate constants was done microcanonically, performed at the E-resolved level in one-dimensional master equation calculations. For all other reactions, the barriers are sufficiently high that we expect variational effects to be negligible. For these cases, the conventional transition state theory (CTST) was used to predict the rate constants with the rigid rotor harmonic oscillator (RRHO) approximation, except for the internal rotations which were treated as hindered rotors. The asymmetric Eckart model[51] was implemented to consider the tunneling effect.

The harmonic-oscillator approximation is typically not appropriate for internal rotations and can introduce significant errors in rate constant calculations. To address this, we explicitly treated low-frequency torsional motions, specifically the internal rotations of the phenyl (C6H5) and/or naphthyl (C10H7), as one-dimensional hindered rotors for major reaction pathways. The hindrance potentials of internal rotors were computed via relaxed dihedral scans at 10° increments at the M06-2X/6-31G(d) level of theory[39]. For the entrance channel, configurations along the MEP exhibit internal rotational motions and chemical structures analogous to those of the transition state. Consequently, the torsional potentials derived from the transition state structure were applied to MEP configurations. This approximation is justified by the structural similarity across the reaction coordinate and is expected to have minimal impact on the final rate constants.

In our master equation simulations, the CSE approach was used to obtain reaction rate constants. For shallow wells, the eigenvalues of related chemical reactions may overlap with the continuum of internal energy relaxation eigenvalues (IEREs). In such scenarios, the well-merging approach implemented in the MESS code was utilized to bind the equilibrating species into a new bound species, and the total number of species was reduced accordingly. To ensure reasonable kinetic predictions for important reaction pathways, we ensured that the maximum ratio of CSE to IERE was controlled within reasonable limits. For particularly challenging cases, only the rate coefficients at the high-pressure limit were determined and provided.

-

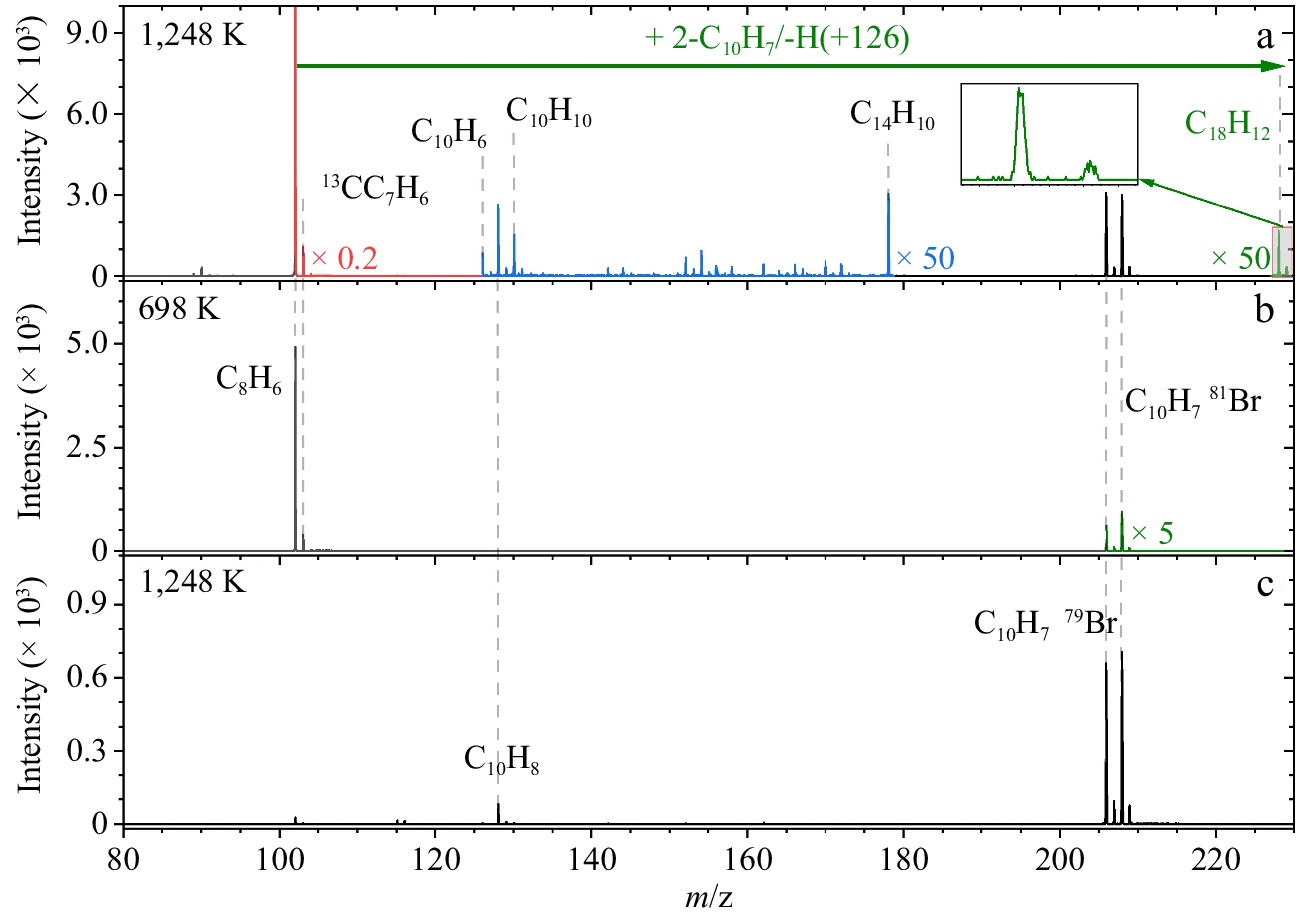

A continuous beam of 2-naphthyl radicals was generated in situ by the rapid thermal decomposition of 2-bromo-naphthalene, which was carried by argon into the flow reactor. Excess amounts of phenylacetylene mixed and reacted with 2-naphthyl radicals at 5 Torr and 1,248 K. Figure 1 presents SVUV-PI-MBMS spectra obtained from the flow reactor experiments of the reaction of 2-naphthyl and phenylacetylene at a photon energy of 9.5 eV. Figure 1a shows the mass spectra of products generated from the reaction between 2-naphthyl radicals and phenylacetylene at 1,248 K. Figure 1b and c are measurements of the control experiments, of which Fig. 1b presents the mass spectra of products of the 2-naphthyl/phenylacetylene reaction at 698 K and Fig. 1c presents the mass spectra of only 2-bromo-naphthalene as reactant at 1,248 K.

Figure 1.

Mass spectra of the products in flow reactor recorded at a photon energy of 9.5 eV. (a) The reaction of 2-naphthyl and phenylacetylene recorded at 1,248 K. Strong ion peaks (red) and weak ion peaks (blue and green) are multiplied by factors of 0.2 and 50 for clarity, respectively. (b) 2-Naphthyl/phenylacetylene reaction recorded at 698 K. Weak ion peaks (green) are multiplied by a factor of 5 for clarity. (c) 2-Bromo-naphthalene only, recorded at 1,248 K.

In Fig. 1, mass peaks of m/z 206 and 208 correspond to the 79Br-isotope and 81Br-isotope of 2-bromo-naphthalene that readily decompose to the 2-naphthyl radicals. The mass peak m/z 128 at 1,248 K is naphthalene (C10H8), derived from 2-naphthyl radicals, according to the observations in Fig. 1c. The aryl radicals were also not detected in previous studies employing an analogous molecular beam sampling setup at the reactor outlet[25,26,52]. It is speculated that such aryl radicals are likely to recombine with free H radicals within the residence time of the reactor or abstract H atoms from ambience via wall-reactions. From Fig. 1b, at 698 K no new mass peaks are generated apart from the mass peaks of 2-bromo-naphthalene and phenylacetylene. This indicates that 2-bromo-naphthalene does not decompose at this temperature.

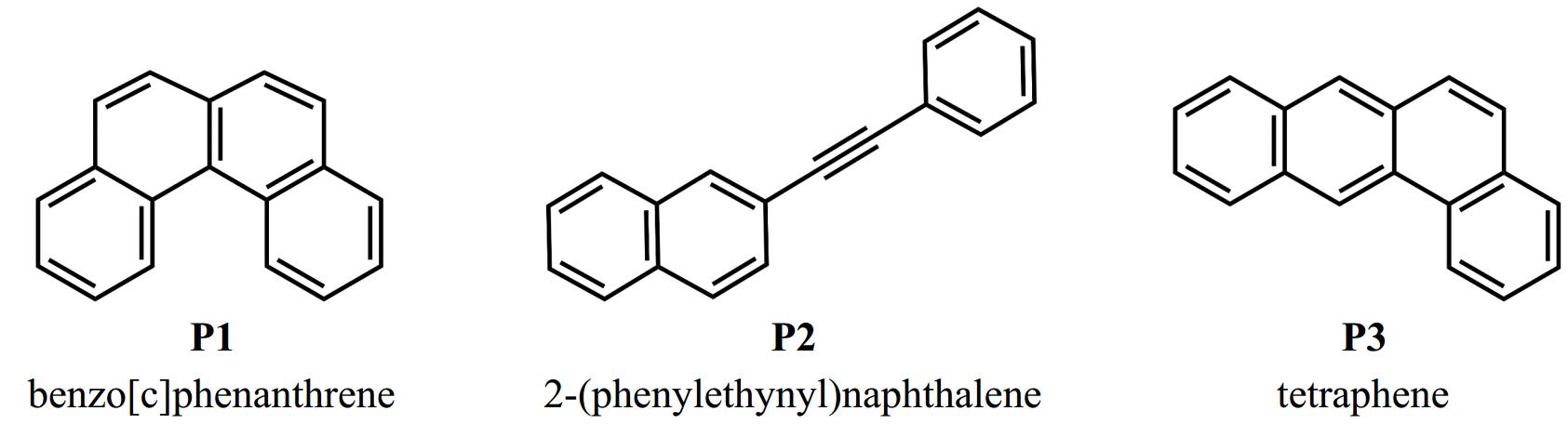

Mass peaks of m/z 178 and 228 appear exclusively in Fig. 1a compared to the control experiment of Fig. 1b, indicating that the corresponding products formed from 2-naphthyl/phenylacetylene reaction. The mass peak m/z 228 (C18H12) originates from 2-naphthyl/phenylacetylene reaction through losing an H atom. These products could be benzo[c]phenanthrene (P1 in Fig. 2), 2-phenylethynyl-naphthalene (P2 in Fig. 2), and/or tetraphene (P3 in Fig. 2). The mass peak at m/z 178 is hypothesized to be a byproduct of side reactions other than the product of 2-naphthyl/phenylacetylene. Specifically, the mass peak m/z 178 was also observed in our previous experiments of the 1-naphthyl/phenylacetylene reaction[25]. The photoionization efficiency (PIE) curve of m/z 178 measured there was perfectly reproduced by the reference curve of diphenylacetylene. Because the phenyl radicals were produced in this reaction, the mass peak m/z 178 (C14H10) was deduced to be diphenylacetylene formed via the phenyl/phenylacetylene reaction. In this study, because of the detection of naphthalene (C10H8), 1-naphthyl/phenylacetylene reaction could occur as a side reaction. As a result, we infer that the mass peak m/z 178 may also be diphenylacetylene formed via the recombination of phenyl and phenylacetylene. The mass peak m/z 229 can be assigned to 2-styrylnaphthalene radical (int1 in Fig. 3), which is the initial adduct of 2-naphthyl/phenylacetylene reaction, and/or the isotopomer of C18H12 (13CC17H12).

Figure 2.

Candidate molecular structures for C18H12 products observed in 2-naphthyl/phenylacetylene reaction.

Figure 3.

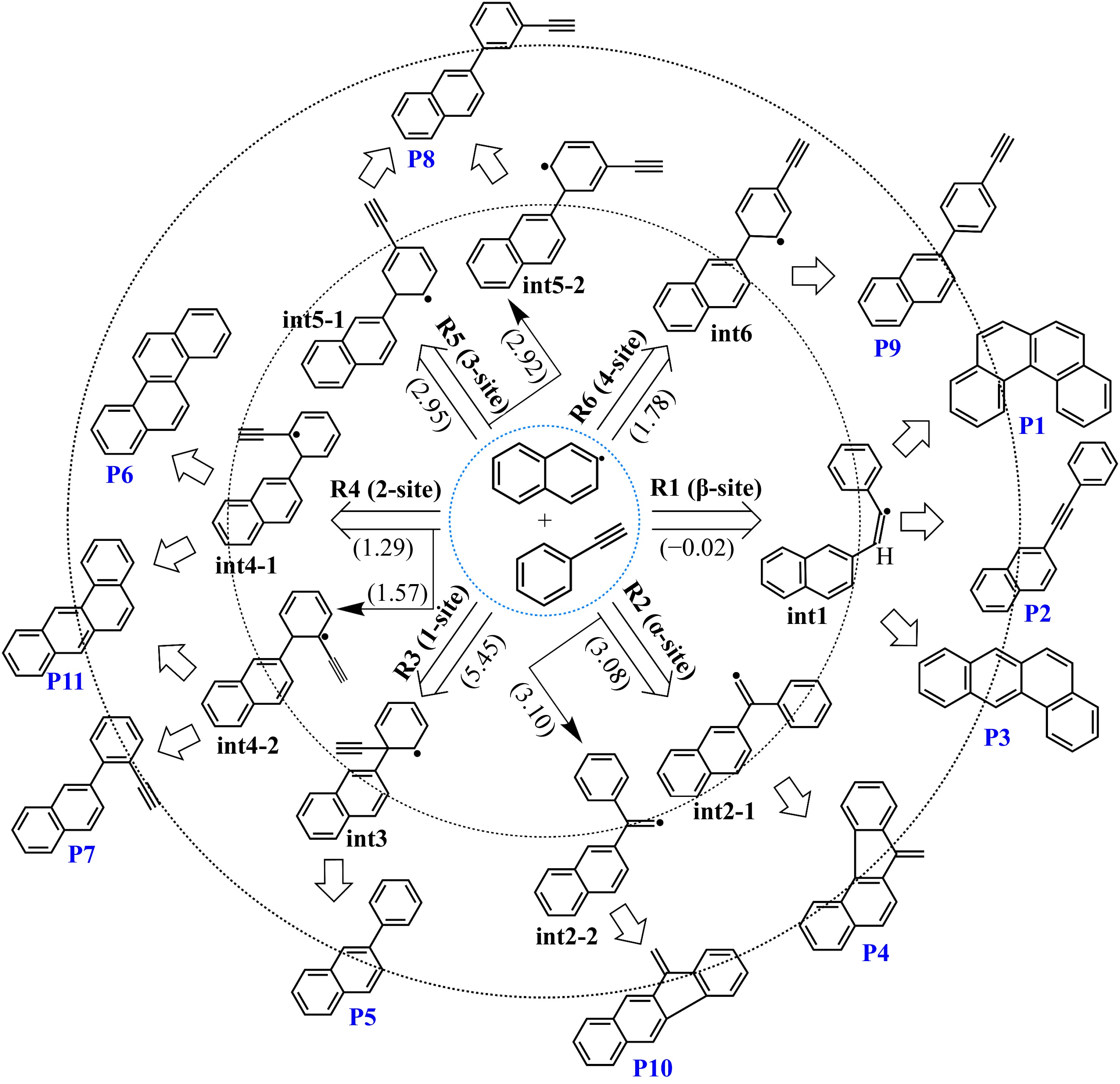

Initial adducts and major products of the 2-naphthyl/phenylacetylene reaction at different sites. The numbers in brackets represent the transition state energies of initial addition steps.

In addition to the products discussed above, we also observed peaks at m/z 126 and 130, which are also absent in the control experiments. These products are speculated to originate from the subsequent chemistry of naphthalene. The m/z 126 peak is inferred to be C10H6 formed through the dehydrogenation of naphthalene (C10H8 → C10H6 + H2) or the dehydrogenation of 2-naphthyl radicals (2-C10H7 → C10H6 + H). Additionally, the hydrogen abstraction from 2-naphthyl radicals by active radicals like H (2-C10H7 + H → C10H6 + H2) might serve as another formation route. The m/z 130 peak may be dihydronaphthalene (C10H10) from the hydrogenation of naphthalene. Additionally, C10H10 may form through side reactions involving the cyclopentadienyl radical (C5H5) and cyclopentadiene (C5H6), as both species are detected in our experiments. Supplementary Fig. S1 shows the mass peaks from m/z 60 to 135, where mass peaks m/z 65 and 66 correspond to cyclopentadienyl radical C5H5 and cyclopentadiene C5H6, respectively. It is proposed that C10H10 could form through the addition of cyclopentadienyl radical to cyclopentadiene followed by hydrogen loss: C5H5 + C5H6 → C10H11 → C10H10 + H[7]. C10H10 might also form via a direct combination of two cyclopentadienyl radicals (C5H5 + C5H5→ C10H10)[53].

Initial additions of 2-naphthyl and phenylacetylene

-

2-naphthyl radicals can be added to phenylacetylene at six different reaction sites. To investigate the detailed kinetics of the recombination reaction between 2-naphthyl and phenylacetylene, we carried out quantum chemical calculations to obtain the potential-energy profiles of the six addition reaction systems. Figure 3 presents the major intermediates and products of the reaction network. From the Fig. 3, R1 to R6 represents the initial addition channels of 2-naphthyl radicals onto the six carbon sites of phenylacetylene, i.e., the β-carbon, α-carbon, and the four aromatic carbons. And int1 to int6 denote the initial adducts formed from the combination of 2-naphthyl and phenylacetylene. P1 to P11 are the final aromatic products on the surfaces of 2-naphthyl + phenylacetylene.

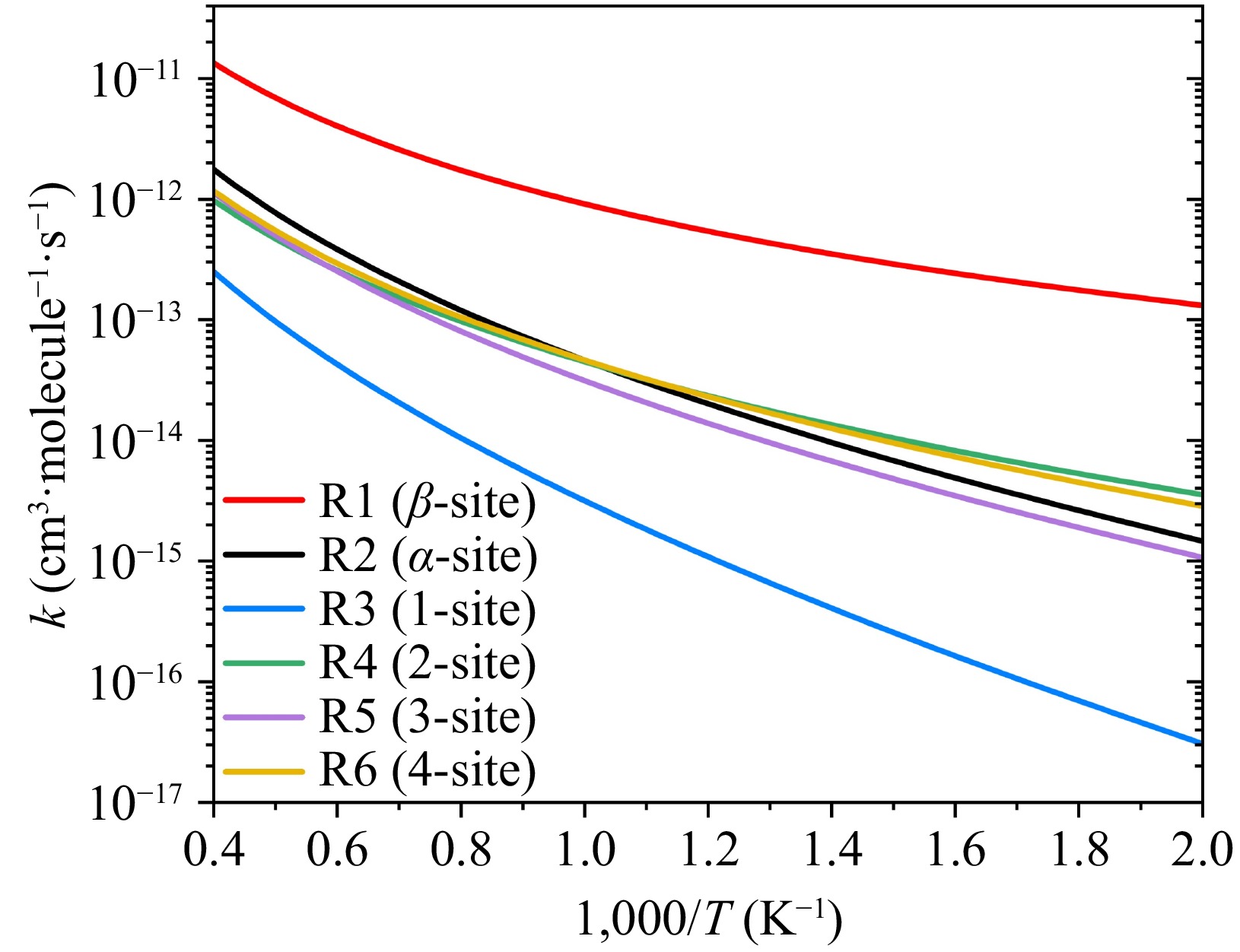

As illustrated in Fig. 3, our quantum chemical calculations reveal that the addition of 2-naphthyl radicals to the β-carbon of the alkynyl group in phenylacetylene (R1 channel) exhibits the lowest 'energy barrier', calculated as -0.02 kcal/mol, which is effectively isoenergetic with the bimolecular asymptote. In contrast, additions to the other carbon sites (R2−R6) display significantly higher energy barriers. Among these, the ortho- and para-positions relative to the alkynyl group occur more easily (labeled as 2-site and 4-site in Fig. 3) and are kinetically more accessible. Kinetic predictions for the six entrance channels, computed using transition state theory, further corroborate the overwhelming dominance of β-carbon addition, as indicated in Fig. 4. While the relative ordering of these shallow barriers could theoretically depend on the computational methodology, prior studies of analogous systems, such as phenyl/phenylacetylene and 1-naphthyl/phenylacetylene reactions, demonstrate consistent trends in entrance barrier energetics and reaffirm the β-carbon selectivity[25,26]. The dominance of addition at the β-site would not be changed by using different energy methods. Consequently, all subsequent mechanistic discussions and kinetic analyses focus exclusively on the 2-naphthyl radical addition to phenylacetylene at β-carbon.

Figure 4.

Six initial addition channels for the reaction of 2-naphthyl with phenylacetylene at high-pressure limit.

To assess the multi-reference character of the saddle point of the entrance channel, we performed multi-reference calculations for the saddle point of the prototype phenyl + acetylene recombination system, as such calculations were not feasible for the 2-naphthyl/phenylacetylene reaction. Geometry optimization and frequency analysis were conducted at the CASSCF(11e,11o)/aug-cc-pVTZ level. Single-point energies were refined using NEVPT2 with an (11e,11o) active space and Dunning's correlation-consistent basis sets (cc-pVTZ and cc-pVQZ). We evaluated both fully internally contracted NEVPT2 (FIC-NEVPT2) and strongly contracted NEVPT2 (SC-NEVPT2). For comparison, we also computed the saddle point by employing the same energy scheme as used for the 2-naphthyl/phenylacetylene reaction system, i.e., B2PLYPD3/def2-TZVPP//M06-2X/6-311+G(d,p).

The test results show that the FIC-NEVPT2/CBS(cc-pV[T,Q]Z) barrier (3.02 kcal/mol) closely matches the energy barrier by B2PLYPD3/def2-TZVPP//M06-2X/6-311+G(d,p) (3.08 kcal/mol). The SC-NEVPT2/CBS(cc-pV[T,Q]Z) barrier is slightly higher (3.71 kcal/mol). Moreover, the structures of saddle points using different methods are quite similar, and the distance of the bonding carbons is 2.23 Å (multi-reference) and 2.27 Å (single-reference), respectively. Additionally, we tested MRCI but found it produced anomalous results for the saddle point of the entrance channel.

The test calculations validate our use of single-reference methods for the 2-naphthyl + phenylacetylene reaction system. The B2PLYPD3/def2-TZVPP//M06-2X/6-311+G(d,p) scheme provides qualitatively correct results while remaining computationally tractable for our target system. For the test calculations and results please refer to Supplementary Table S2.

Potential-energy profile

-

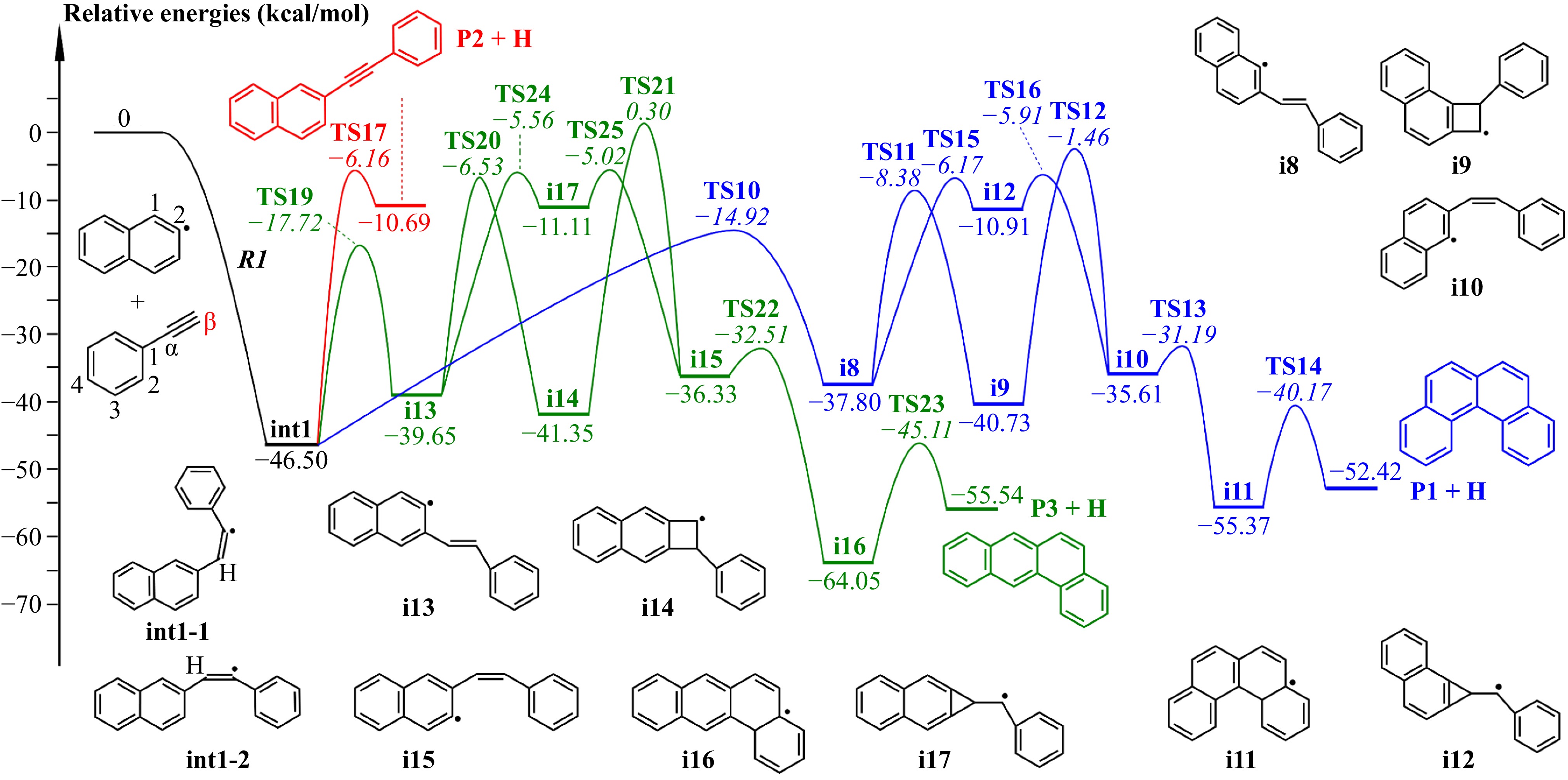

Figure 5 represents the potential-energy profile of the major reaction pathways for the recombination between 2-naphthyl radicals and phenylacetylene. Our master equation simulations focus exclusively on the pathways shown in Fig. 5; the complete potential-energy profile is depicted in Supplementary Fig. S2. The potential-energy profiles of recombinatons occurring at other sites are provided in Supplementary Fig. S3. As shown in Fig. 5, the reaction is initiated by a barrierless addition reaction of 2-naphthyl radicals to phenylacetylene, forming the initial adduct (int1). Since the reacting moieties have two orientations, this adduct exists as two conformational isomers (int1-1 and int1-2). These isomers interconvert via C-C bond rotation with low energy barriers (4.2 and 4.9 kcal/mol), enabling rapid equilibration. Given the negligible barriers, this study disregards the influence of reactant orientation on the overall reaction kinetics.

Figure 5.

Potential-energy profile of 2-naphthyl/phenylacetylene reaction at β-carbon. Numbers in normal type represent relative energies of intermediates and products; numbers in italic type represent transition states energies relative to the reactants. All pathways shown here are included in the master equation calculations.

Starting from the initial adduct int1, the reaction pathways involve multiple possible routes. Among them, H-elimination of int1 yields 2-phenylethynyl-naphthalene (P2) + H. Different isomerization sequences give rise to benzo[c]phenanthrene (P1) + H and tetraene (P3) + H. Specifically, the formation of P2 + H proceeds by overcoming a higher energy barrier of approximately 40 kcal/mol (TS17). As temperature increases, this reaction channel becomes kinetically more important due to the entropy-driven nature of the process. The int1 adduct can also undergo different series of reaction sequences to form P1 and/or P3 PAHs with four aromatic rings. In the sequences to P1 + H (routes in blue, Fig. 5), int1 first undergoes an H-shift via a five-membered ring transition state (TS10) to produce i8 which has a trans-configuration for the alkynyl group. The trans-configuration structure of i8 can be converted to a cis-configuration structure of i10 via two ways: one way through the formation of intermediate i9 with a quadrilateral structure, and the other way through the formation of intermediate i12 with a triangular structure. According to the quantum chemical calculations results, the formation of i12 with a triangular structure provides an easier pathway in the steric isomerization from i8 to i10. The sequences to form P3 + H (routes in green, Fig. 5) occur via a similar mechanism. To be specific, H-shift from int1 to i13 (TS19) via a five-membered ring transition state with a barrier of about 29 kcal/mol. Steric isomerization converts the trans-structure in i13 to the cis-structure in i15, via a quadrilateral structure (i14) or a triangular structure (i17). Likewise, the isomerization via the triangular structure appears to be more favored in terms of energy.

While thermochemical analysis suggests potential isomerization pathways for int1 involving four-membered ring transition states (i.e., H-shifts from the phenyl ring to the radical site via TS1 and TS9), these pathways are kinetically unfavorable due to significantly higher energy barriers compared to the blue and green routes in Fig. 5. Consequently, these high-barrier pathways are excluded from the main discussion, as they play a negligible role in the reaction network under studied conditions.

Reaction kinetics

-

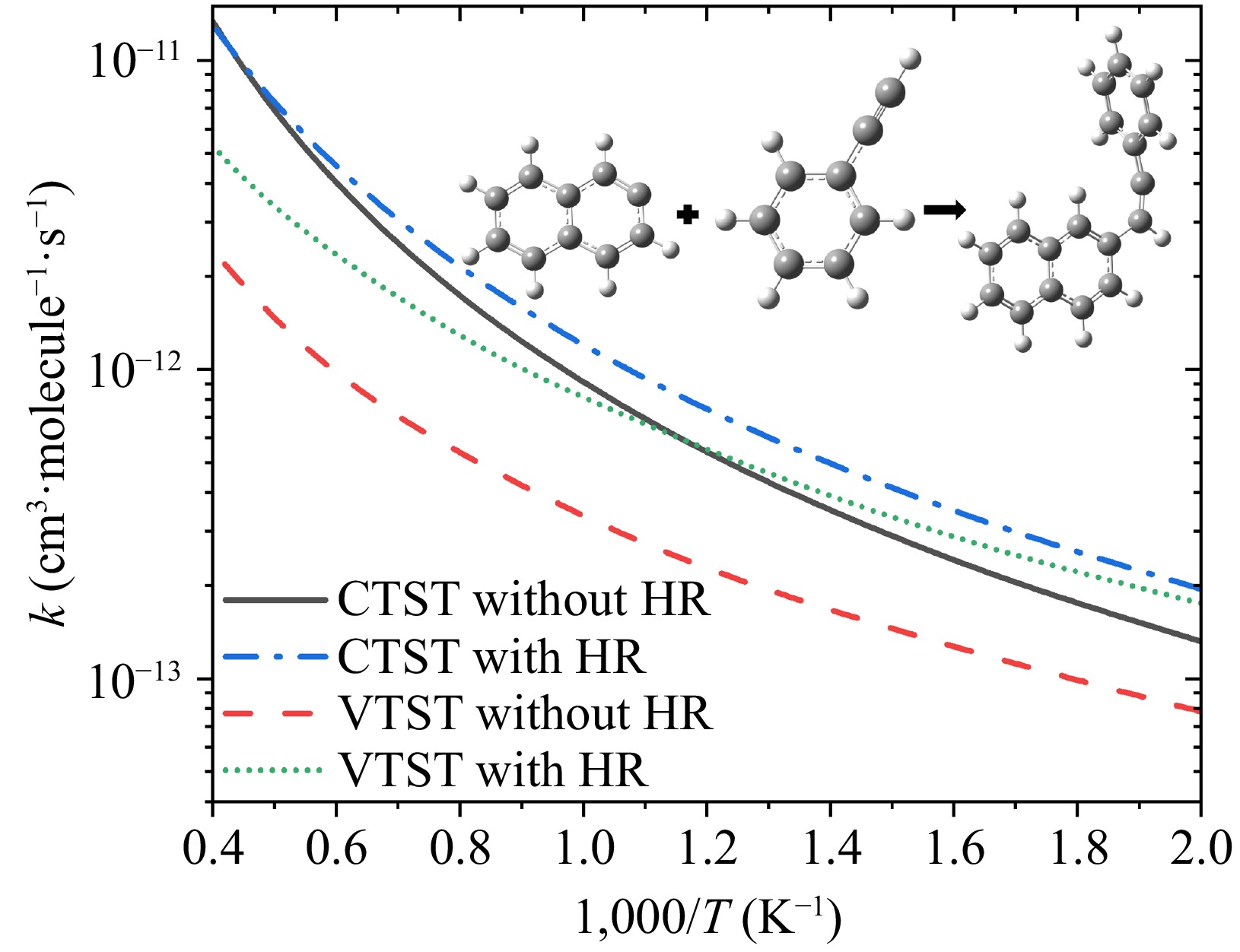

Given the absence of distinct energy barriers in the entrance channel R1, we employ the VTST theory to account for dynamic effects when calculating rate constants. Additionally, the hindered rotor treatment is implemented for low-frequency modes that correspond to internal rotational motions. Figure 6 illustrates the combined impact of these kinetic treatments on the high-pressure limit rate coefficients for reaction R1. From this figure, the variational effect and hindered rotor effect both play a crucial role in predicting accurate rate constants. The variational effect reduces rate constants especially at high temperatures due to tighter transition state localization; the hindered rotor treatment enhances rate coefficients, particularly at temperatures of 800 to 1,700 K, by accurately modeling low-frequency rotational modes. For instance, comparing VTST calculations with and without hindered rotor corrections, the former increases rate constants by a factor of 1.2−1.4 across all temperatures. Between calculations with hindered rotor treatment, the variational effect reduces rate constants by 10%−60% over the studied range. Thus, incorporating both variational and hindered rotor effects is critical for reliable predictions in the entrance channel R1.

Figure 6.

Comparison of high-pressure limit rate coefficients for the entrance channel R1, with the four lines representing: (a) CTST without HR: CTST without hindered rotor treatment, black solid line; (b) CTST with HR: CTST with hindered rotor treatment, blue dash dot line; (c) VTST without HR: VTST without hindered rotor treatment, red dashed line; and (d) VTST with HR: VTST with hindered rotor treatment, green short dot line.

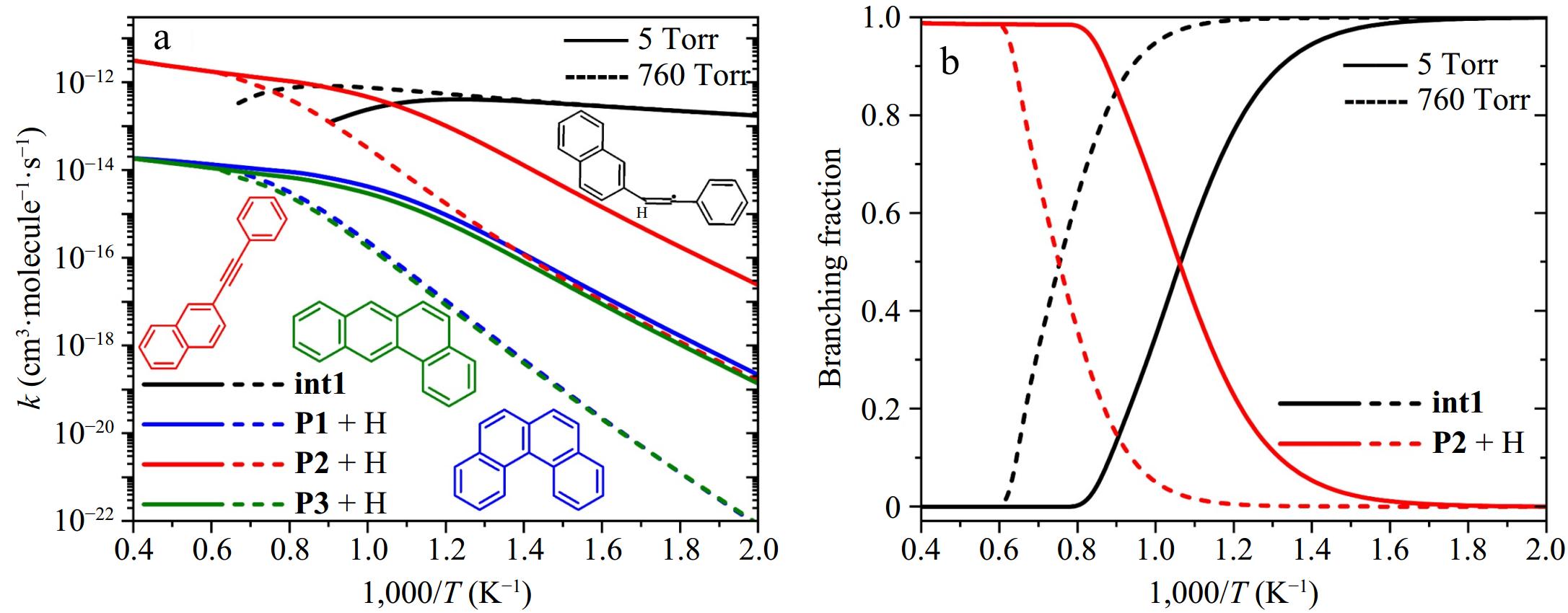

Figure 7 shows the rate coefficients and branching fractions of the primary elementary reactions involving 2-naphthyl and phenylacetylene, including stabilization into the 2-styrylnaphthalene radical (2-naphthyl + phenylacetylene → int1), formally-direct formation reactions of benzo[c]phenanthrene (P1) + H, 2-phenylethynyl-naphthalene (P2) + H, and tetraphene (P3) + H at pressures of 5 and 760 Torr. At 5 Torr, stabilization into int1 predominates below 950 K, while the formally-direct formation of P2 + H becomes dominant at higher temperatures. Elevated pressure (760 Torr) enhances collisional stabilization of int1, shifting the dominance of P2 + H formation to higher temperatures due to increased competition between stabilization and reaction kinetics. At both pressures, the pathways forming P3 + H and P1 + H exhibit comparable contributions to the product distribution at high temperatures.

Figure 7.

(a) Rate coefficients, and (b) branching fractions for elementary reactions with 2-naphthyl + phenylacetylene as reactants: the stabilization of 2-styrylnaphthalene radical (int1), the formation of benzo[c]phenanthrene (P1) + H, 2-(phenylacetylene)-naphthalene (P2) + H, and tetracene (P3) + H. Solid and dashed lines represent results at 5 and 760 Torr, respectively.

Kinetic calculations reveal that the 2-naphthyl/phenylacetylene reaction system is governed by two critical channels: the stabilization of int1 and formation of 2-phenylethynyl-naphthalene (P2) + H. While P2 + H can arise directly from the reactants (P0), our results confirm an additional pathway via sequential reactions involving int1. The observed mass peak m/z 228 aligns with P2 (C18H12), supporting our experimental detection. The mass peak m/z 229 likely corresponds to the 2-styrylnaphthalene radical (int1), though contributions from a 13C isotopomer of P2 (13CC17H12) cannot be ruled out. In addition, the reaction pathways of P1 + H and P3 + H exhibit negligible contributions to the overall kinetics, primarily due to the higher overall barriers.

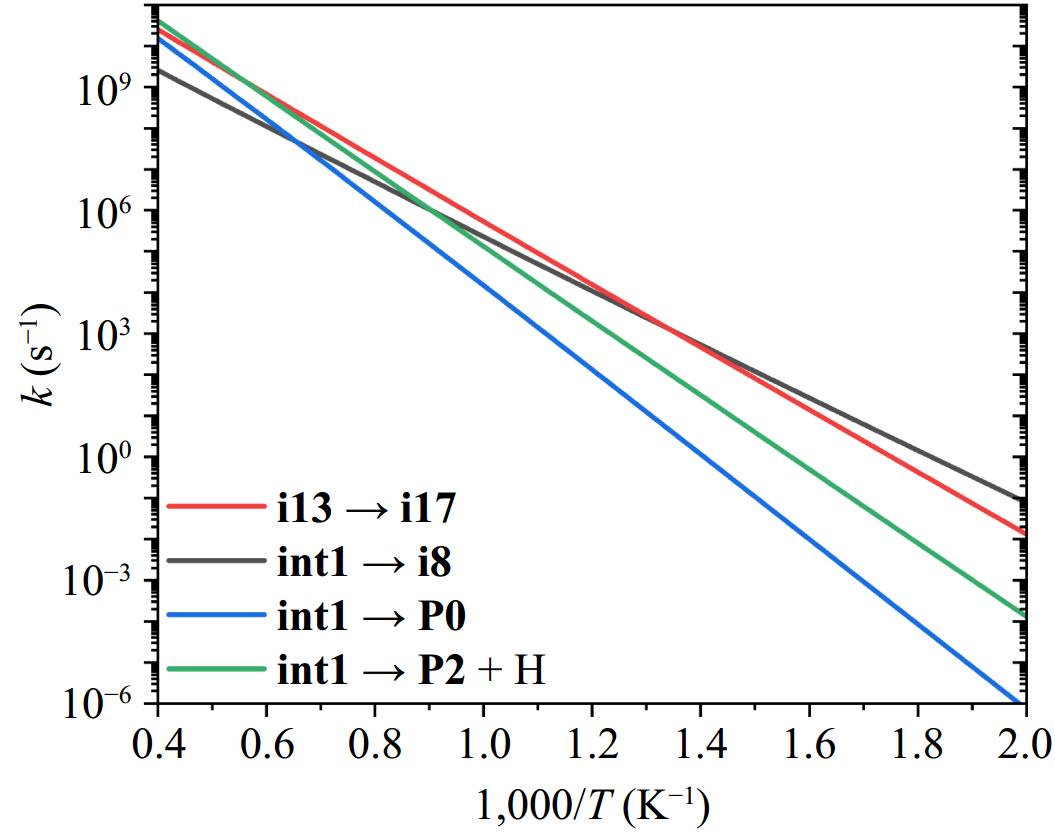

Based on the preceding analysis, int1 stabilization emerges as the significant path for the 2-naphthyl/phenylacetylene reaction under medium-to-low temperatures. Consequently, the subsequent decomposition of int1 is of great significance to the formation of larger PAH molecules. The high-pressure limit (HPL) rate coefficients for the decomposition pathways of int1 are shown in Fig. 8. For the reaction sequence int1 to P1 + H, two ways are identified: (a) the way via i9 is kinetically negligible and excluded based on computational results; (b) the way via i12 involves a rate-controlling step (int1 → i8), which exhibits the lowest rate constants above 500 K (HPL) and the second-highest energy barrier (31.58 kcal/mol) in this sequence. Although the subsequent step (i8 → i12) has a slightly higher barrier (31.63 kcal/mol), its rate constants exceed those of int1 → i8 above 500 K (HPL). Thus, int1 → i8 governs the overall kinetics of the int1 → P1 + H sequence. For simplicity, we approximate the overall kinetics using this rate-controlling step. Similarly, the int1 to P3 + H sequence is represented by the rate-controlling step of i13 to i17. Below 1,100 K, int1 undergoes isomerization sequences leading to the products of P1 + H and P3 + H; however, the cumulative energy barriers suppress the overall rate constants compared to individual rate-controlling steps. At temperatures exceeding 1,800 K, the C-H β-scission pathway (int1 → P2 + H) dominates due to its largest rate constants. Additionally, int1 redissociation to 2-naphthyl + phenylacetylene becomes increasingly competitive at elevated temperatures, driven by entropic effects.

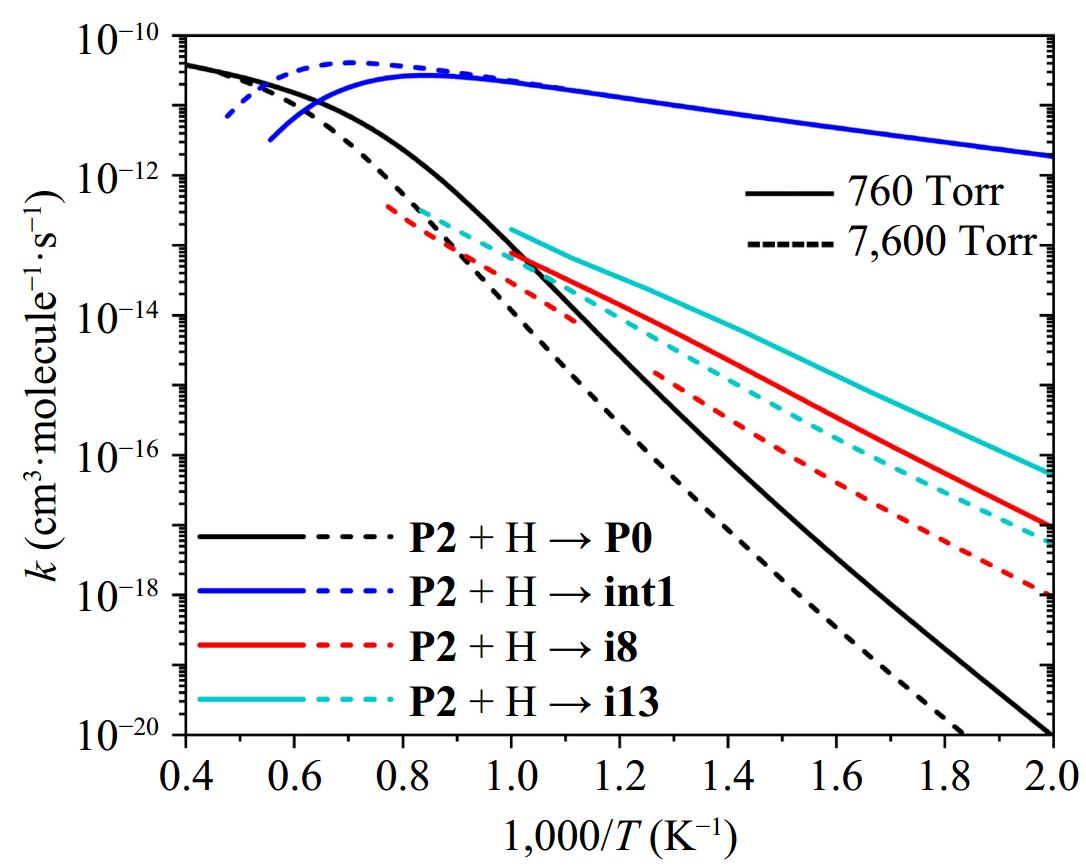

As discussed earlier, 2-phenylacetyl-naphthalene (P2) is a primary product of the reaction between 2-naphthyl and phenylacetylene. P2 is anticipated to undergo subsequent reactions with small radicals, particularly through H-atom addition, which represents a critical pathway in its chemical evolution. The H radical can add to P2 at either carbon site of the alkynyl group; however, the potential-energy profile in Fig. 5 indicates preferential addition at the β-carbon adjacent to the phenyl group. Figure 9 displays the rate coefficients for the dominant product pathway of the P2 + H reaction at this specific β-carbon site under pressures of 760 and 7,600 Torr. At 760 Torr, the reaction predominantly yields int1 below 1,550 K via collisional stabilization of the initially formed excited adduct. As temperature rises, the formally direct mechanism becomes dominant, leading to the regeneration of 2-naphthyl and phenylacetylene (P0). At elevated pressures (e.g., 7,600 Torr), the stabilization of int1 persists to higher temperatures, and chemical reactions need to occur at higher energy levels to compete effectively with the collisional stabilization.

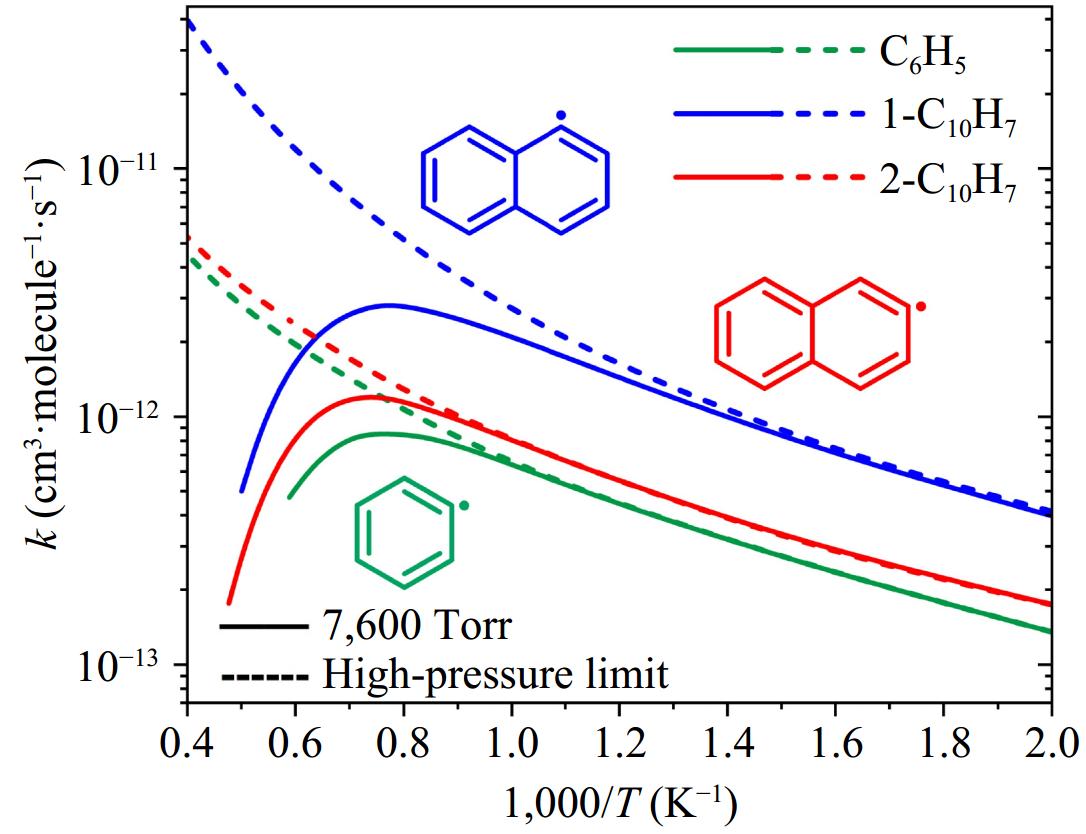

Figure 10 compares the rate coefficients for the formation of initial adducts in the phenyl/phenylacetylene, 1-naphthyl/phenylacetylene, and 2-naphthyl/phenylacetylene reaction systems at 7,600 Torr. The results reveal that 1-naphthyl radicals (1-C10H7) exhibit higher reactivity toward addition to phenylacetylene compared to 2-naphthyl (2-C10H7), and phenyl (C6H5) radicals. This observation may be explained by the fact that the energy barrier of the entrance channel for the 1-naphthyl/phenylacetylene reaction is −0.53 kcal/mol, which is lower than those of the 2-naphthyl/phenylacetylene (−0.02 kcal/mol) and phenyl/phenylacetylene (0.43 kcal/mol) reactions. The impact of pressure on the rate coefficients of entrance channels is negligible at low temperatures but grows increasingly pronounced at elevated temperatures. This temperature-dependent pressure sensitivity aligns with the significance of collisional stabilizations under high-temperature, high-pressure conditions.

Figure 10.

Comparison of rate coefficients for the formation of initial adducts in the reactions of phenyl/phenylacetylene, 1-naphthyl/phenylacetylene, and 2-naphthyl/phenylacetylene. Solid and dashed lines represent the values at 7,600 Torr and high-pressure limit, respectively.

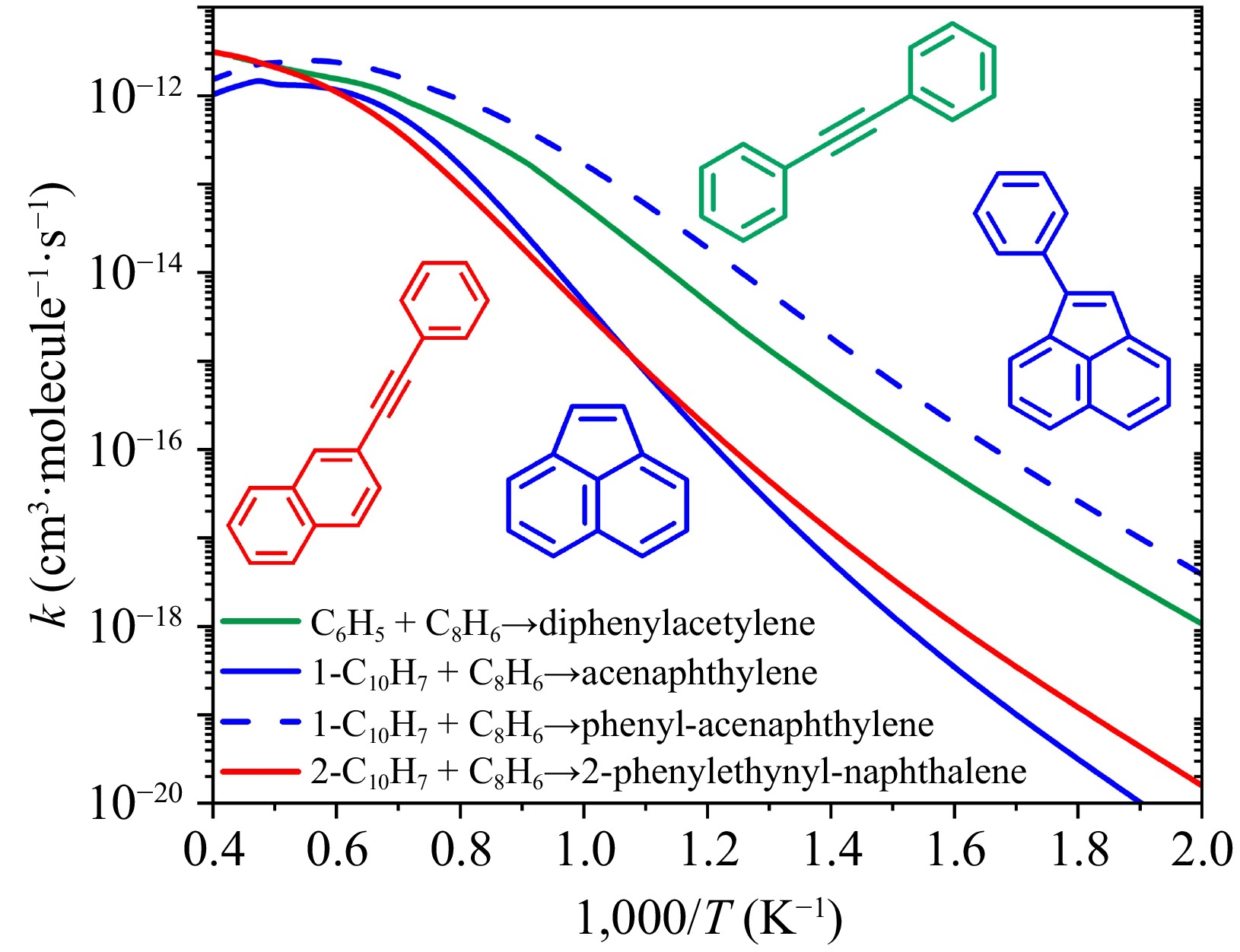

Figure 11 presents the temperature-dependent rate constants for aromatics formation via formally-direct pathways in reactions between phenylacetylene and phenyl, 1-naphthyl, or 2-naphthyl radicals. These pathways proceed as formally-direct reactions, which traverse through multiple transition states to directly yield final products without stable intermediates. Structurally, phenyl and 2-naphthyl radicals possess free-edge active sites, while the 1-naphthyl radical features a zigzag-edge site. For radicals with a 'free' edge site (phenyl and 2-naphthyl), reactions with phenylacetylene proceed via C–H β-scission of the initially activated adduct, directly forming larger aromatics: diphenylacetylene (phenyl + phenylacetylene), and 2-phenylethynylnaphthalene (2-naphthyl + phenylacetylene). In these products, the aromatic rings are connected through a triple bond (–C≡C–). These reactions are characteristic of entropy-driven processes and become dominant at elevated temperatures. For the zigzag-edge 1-naphthyl radical, its reaction with phenylacetylene mainly produces acenaphthylene and phenyl-acenaphthylene at high temperatures. Across most temperatures, phenyl-acenaphthylene remains the dominant species, though acenaphthylene gains significance at high temperatures and should not be neglected.

Figure 11.

Rate constants for aromatic formation via formally-direct mechanism in reactions between phenylacetylene (C8H6) and three aryl radicals at 7,600 Torr. Products in green and red correspond to phenyl and 2-naphthyl, which have 'free' edge sites; and products in blue correspond to 1-naphthyl, which has 'zigzag' edge sites.

-

This study combines theoretical calculations and experimental analyses to explore the reaction kinetics of 2-naphthyl radicals with phenylacetylene, elucidating mechanisms underlying the growth of naphthalene with the assistance of phenylacetylene. Key findings include:

(1) The addition reaction of 2-naphthyl radicals and phenylacetylene occurs preferentially at the β-carbon of the alkynyl group. At low temperatures, collisional stabilization dominates, forming the initial adduct (int1). At elevated temperatures, the activated adduct populates higher-energy states, enabling the formally-direct formation of 2-phenylethynyl-naphthalene (P2) + H.

(2) The decomposition behaviors of 2-styrylnaphthalene (int1) show an apparent temperature dependence. At low/medium temperatures, int1 undergoes isomerization to yield benzo[c]phenanthrene (P1) + H and tetraphene (P3) + H. At elevated temperatures, int1 primarily dissociates via the C-H β-scission to yield 2-phenylethynyl-naphthalene (P2) + H.

(3) 1-Naphthyl radicals (with a 'zigzag' edge site) exhibit higher reactivity than phenyl and 2-naphthyl radicals (with 'free' edge site) except at the very high-temperature end, resulting in aromatic growth by an additional six-carbon ring and an additional five-carbon ring.

(4) The experimentally measured species with m/z 228 aligns with 2-phenylethynyl-naphthalene (P2, C18H12), confirmed by kinetic analysis to originate both directly from the 2-naphthyl/phenylacetylene reactants and secondary reactions of int1.

The fitted modified Arrhenius parameters of the rate constants for all elementary reactions in Fig. 5 are provided in Supplementary Table S3. The single-point energies, vibrational frequencies, and Cartesian coordinates for all stationary points in Fig. 5 are presented in Supplementary Table S4.

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52276101 and 52474213).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Ye L; data collection, analysis and interpretation of results: Yang T, Zhang Z; writing - draft manuscript preparation: Yang T; funding acquisition: Ye L; Writing - manuscript revision: Ye L, Wang D. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary information files.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 Standard enthalpies of formation at different methods as well as data from NIST[1].

- Supplementary Table S2 Reaction rate constants of different channels (HPL: High-pressure limit).

- Supplementary Table S3 Zero-point energies and electronic energies of reactants and transition state for the addition reaction of phenyl + acetylene with multi- and single-reference methods.

- Supplementary Table S4 Energies, vibrational frequencies, and Cartesian coordinates for all optimized structures. The frequencies and geometries are obtained at M06-2X/6-311+G(d,p) level. The energies are calculated at B2PLYPD3/def2-TZVPP level.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Complete potential energy profile for recombination reactions between 2-naphthyl and phenylacetylene at β−carbon.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Potential energy profiles for recombination reactions between 2-naphthyl and phenylacetylene at alpha-, 1-, 2-, 3-, and 4-sites.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 Mass spectrum of the 2-naphthyl/phenylacetylene reaction in the range of m/z = 60−135 at 1,248 K, recorded at a photoionization energy of 9.5 eV. Weak ion peaks (purple and blue) are multiplied by a factor of 50 for clarity.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Yang T, Wang D, Zhang Z, Ye L. 2025. Elucidating the recombination kinetics of 2-naphthyl radicals with phenylacetylene. Progress in Reaction Kinetics and Mechanism 50: e012 doi: 10.48130/prkm-0025-0012

Elucidating the recombination kinetics of 2-naphthyl radicals with phenylacetylene

- Received: 04 December 2024

- Revised: 26 March 2025

- Accepted: 06 May 2025

- Published online: 02 July 2025

Abstract: Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) serve as critical precursors in soot formation, and understanding their formation mechanisms is fundamental for controlling pollutant emissions during the combustion of carbonaceous fuels, such as petrochemical derivatives. This study combines experimental and theoretical techniques to explore the radical-molecule reactions of 2-naphthyl radicals with phenylacetylene (also known as ethynylbenzene), which is potentially a ring-growth pathway for 2-naphthyl. The potential-energy profile was investigated at B2PLYP-D3/def2-TZVPP//M06-2X/6-311+G(d,p) level of theory. Temperature- and pressure-dependent (500–2,500 K and 3–7,600 Torr) rate constants were obtained from RRKM/master-equation simulations. Although the 2-naphthyl radical can add to multiple sites on phenylacetylene, the kinetics is overwhelmingly governed by the addition of the terminal acetylene carbon (β-carbon). At 760 Torr, the stabilization of initial activated adduct into 2-styrylnaphthalene radical prevails below 1,300 K, while the formally-direct channel producing 2-phenylethynyl-naphthalene and H becomes favorable above 1,300 K. For subsequent reaction of 2-styrylnaphthalene radical (i.e., the initial adduct), the sequential isomerization reactions via intramolecular hydrogen transfer dominate at low temperature, whereas the C-H β-scission to form 2-phenylethynyl-naphthalene and H becomes prominent at high temperature. The synchrotron vacuum ultraviolet photoionization molecular beam mass spectrometry experiment indicates a mass peak m/z 228 from the reaction between 2-naphthyl and phenylacetylene with a photon energy of 9.5 eV. Based on experimental measurements and kinetic analysis, the m/z 228 peak is deduced to be 2-phenylethynyl-naphthalene. Kinetic analysis of three aryl radicals (i.e., phenyl, 1-naphthyl, and 2-naphthyl) with phenylacetylene reveals that 1-naphthyl, which features a 'zigzag' edge site, exhibits higher reactivity compared to phenyl and 2-naphthyl radicals, both of which possess 'free' edge sites (the phenyl/phenylacetylene and 1-naphthyl/phenylacetylene reactions were studied in Combustion and Flame, 2022, 243, 112,014 and Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2021, 143, 20,710, respectively). This trend holds across a wide temperature range, except at the very high-temperature end. These findings significantly deepen our understanding of the formation and growth mechanisms of PAHs in combustion systems, providing critical insights into the chemical behavior of aryl radicals and their contributions to the formation and evolution of PAHs.