-

In nature, plants are sessile organisms that are exposed to many environmental stressors such as salinity, drought, heat, and other abiotic and biotic factors throughout their life. Among these, salinity negatively affects plant growth and threatens global food security[1]. Plants have developed a variety of methods for the incorporation of long-term and short-term mitigation strategies, such as morphological, metabolic, physiological, and molecular, ensuring global food security[2]. Salinity stress negatively influences plant growth, particularly root growth, causing water and nutrient deficits in the soil, leading to suppressed plant growth, ion toxicity, osmotic stress, and eventually plant death[3]. Other adverse effects include stomatal closure, reduced carbon dioxide exchange, enhanced lipid peroxidation, and formation of reactive oxygen species such as O2−, H2O2, and OH−, triggering membrane oxidative damage and accumulation of malondialdehyde (MDA), which further disrupts different metabolic processes and physiology[1].

Phytohormones offer a novel and dynamic defense system to cope with salinity stress. Phytohormones are small chemical molecules that are pivotal not only in plant development and growth but also in diverse environmental conditions. Phytohormones are categorized into stress response hormones (ethylene, jasmonic acid, abscisic acid (ABA), salicylic acid (SA)), and growth-promoting hormones (cytokinins (CK), strigolactones (SL), gibberellins (GA), and brassinosteroids (BR))[4]. Abscisic acid (ABA), a stress hormone, is a critical regulator of plant physiology and plays a pivotal role in salinity tolerance[5]. Additionally, ABA is required for plant growth under normal conditions and includes different components required for its synthesis in molecular signaling, perception, and response[6]. For instance, under stressful conditions, ABA accumulates in plants through ABA biosynthesis, modulating gene expression, and causing physiological alterations, displaying the activation of ABA biosynthesis-associated enzymes and relative alternation in mRNA expression, leading to ABA production and accumulation[1]. The role of ABA has been extensively reviewed and studied; therefore, here, we summarize current research on the dynamic role of ABA in salinity stress in plants.

-

Environmental constraints, particularly salinity, are one of the major factors limiting plant growth in crop plants. Soil salinization, either naturally or due to anthropogenic activities, adversely affects soil properties. Anthropogenic activities account for approximately 20% of global soil salinization[7]. Excessive irrigation has contributed to soil salinity and reduced global land productivity. Approximately 15% of the world's land is affected by soil degradation, including salinization, which leads to desertification (FAO, 2021). With the global population projected to exceed 9 billion by 2050, food production must increase by 57% to meet the demand[8]. Soil salinity poses a critical challenge to sustainable agriculture and threatens progress toward the UN Sustainable Development Goals by 2030.

The most essential component of an ecosystem is salt, which is required at an optimal level. Excessive salt in the soil deteriorates soil chemistry, leading to the disruption of biological processes. The soils in arid and semiarid regions are affected by salinity. Although previous studies have shown that salt-affected regions include Asia, Africa, America, and Australia, it is difficult to estimate the extent of salinization in a specific region. Soil salinization is neither region-specific nor altitude-specific. It varies with location from humid to polar regions and from sea level to high altitude[9]. Soil ecosystems are sensitive to elevated concentrations of salt in the soil, which adversely influences plants adapted to those soils but also affects microflora and soil organisms. For instance, Ivushkin et al.[10] showed that approximately 1 billion hectares of global soil are affected by salinization, and this trend is increasing in more than a hundred countries.

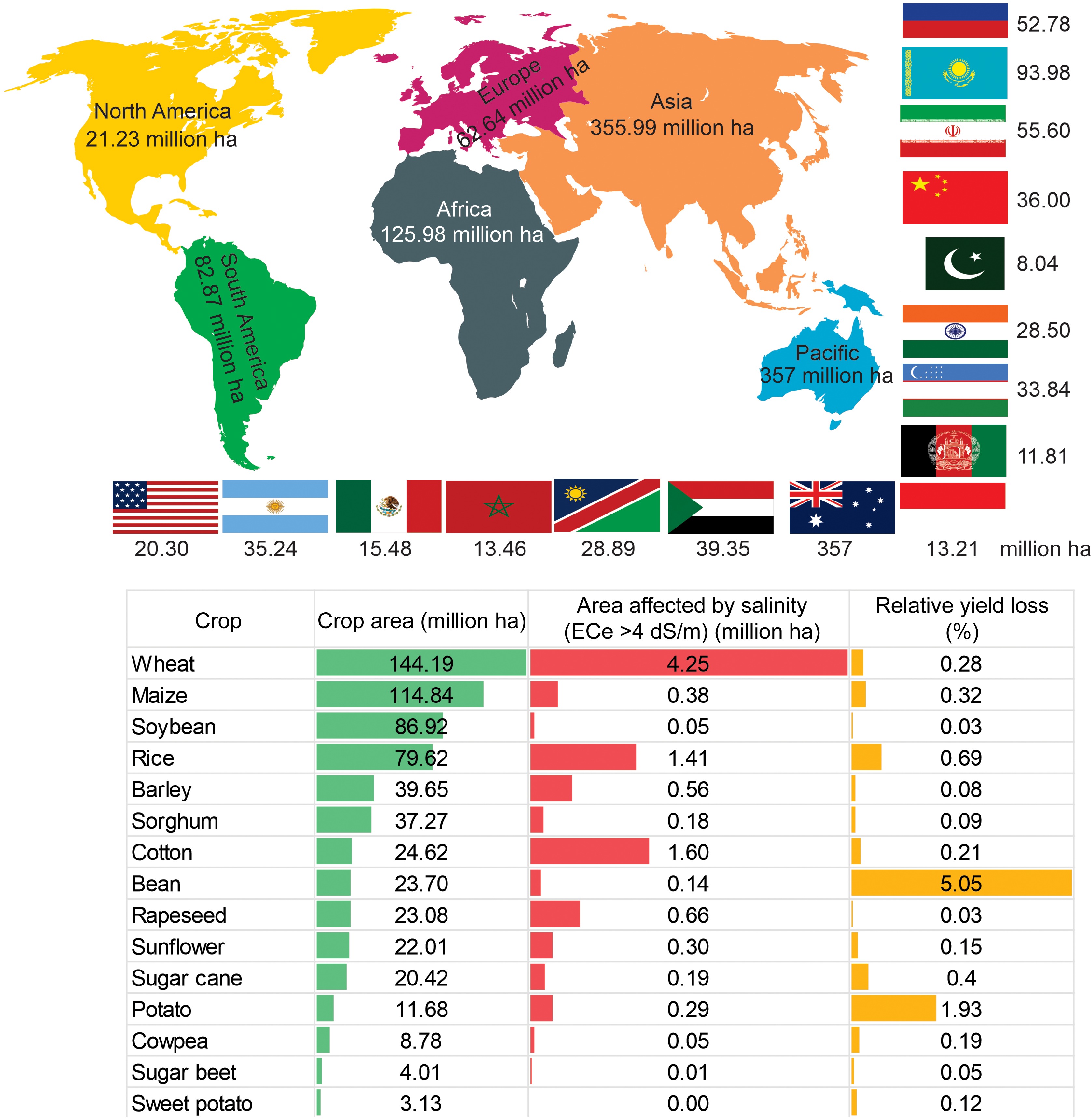

However, a recent survey by FAO 2024 on the global status of salt-affected soils[11] disclosed that increasing the global population with their induced accumulation of salt in soil poses a serious hazard to global agricultural productivity. According to a report, a new estimate of global salt-affected soils amounts to 1,381 million ha (10.7% of the total global land). As shown in Fig. 1, the largest salt-affected areas are found in Australia (357 million ha), Argentina (153 million ha), Kazakhstan (94 million ha), Russia (77 million ha), the United States (73.4 million ha), Iran (55.6 million ha), Sudan (43.6 million ha), Uzbekistan (40.9 million ha), Afghanistan (38.2 million ha), and China (36 million ha). The potential yield losses due to salinity provided the spatial distribution of 15 crops, and the estimated yield loss ranged from 0.03% for soybeans to 5.05% for beans (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Global map of the distribution of salt-affected soil in six continents and major countries affected by salt in each continent (million ha) (upper panel). Relative yield loss due to salinity in specific crops (lower panel). Global crop area (million ha) for each crop cultivation, area affected by salinity (million ha), and percent relative yield loss for each crop (%). The data on the global status of salt-affected soils were sourced from FAO 2024[11].

Altogether, it is apparent that improper management of land leads to salinization, and the situation would worsen if appropriate measures were not considered. Soil management strategies, including proper irrigation techniques, integrating agroforestry, optimal and prescribed use of fertilizers, application of bio-fertilizers, tillage practices, and leaching maintenance, can be applied to prevent future soil salinization[12,13].

-

ABA is a primer regulator of diverse plant responses to stressful environmental conditions, particularly salinity[1]. Under salinity stress, plants accumulate ABA from several stress-related genes. However, under optimal conditions, ABA levels are reduced to basal levels for optimal plant growth. ABA modulation in cells or tissues is a critical factor in the balance between plant defense and growth responses under stressful conditions. This requires intricate control of ABA levels through biosynthesis, metabolism, and transportation in plants[14].

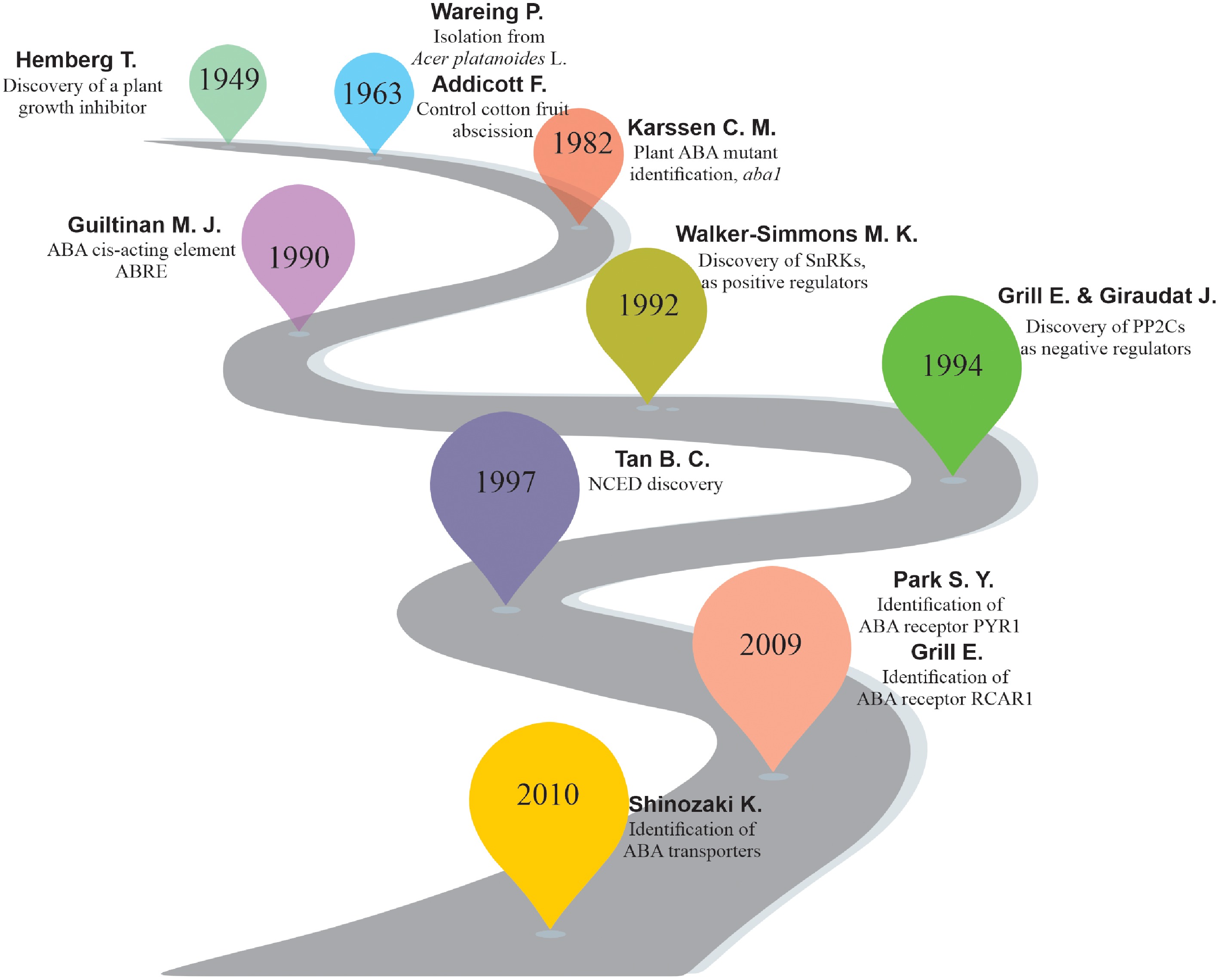

ABA is one of the six key plant hormones known for its role in fruit and leaf abscission. ABA was first reported by Hemberg in 1960 as a water-soluble plant growth inhibitor required for tuber (Solanum tuberosum) and Fraxinus terminal bud dormancy[15,16]. Later on, Eagles & Wareing isolated a growth-inhibiting substance named 'dormin' from the buds of Acer platanoides due to their role in bud dormancy[17]. In the same year, Frederick Addicott discovered a substance that controlled the abscission of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) young fruits, named 'abscisin'. Later he found that 'dormin' and 'abscisin' were the same chemical, so he named it 'abscisic acid' (ABA)[17]. The discovery of ABA pathway mutants (aba1-deficient) in Arabidopsis (1980) provides crucial insights for further research on ABA biology in plants. Subsequently, advances in molecular, genetic, and biotechnological plenty of key transcription regulators/factors, enzymes, transporters, and other genes, such as protein phosphatase 2C (PP2C), Pyrabactin Resistance (PYR)/PYR1-like (PYL)/Regulatory Component of ABA Receptor (RCAR), subclass III sucrose nonfermenting 1-related protein kinases (SnRK), and 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase (NCED), have been discovered (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Brief overview of ABA research progress. The complexity and diversity of the ABA pathway have been revealed through genetic, proteomic, and genomic approaches to elucidate the functions of ABA in agricultural production and plant biology research.

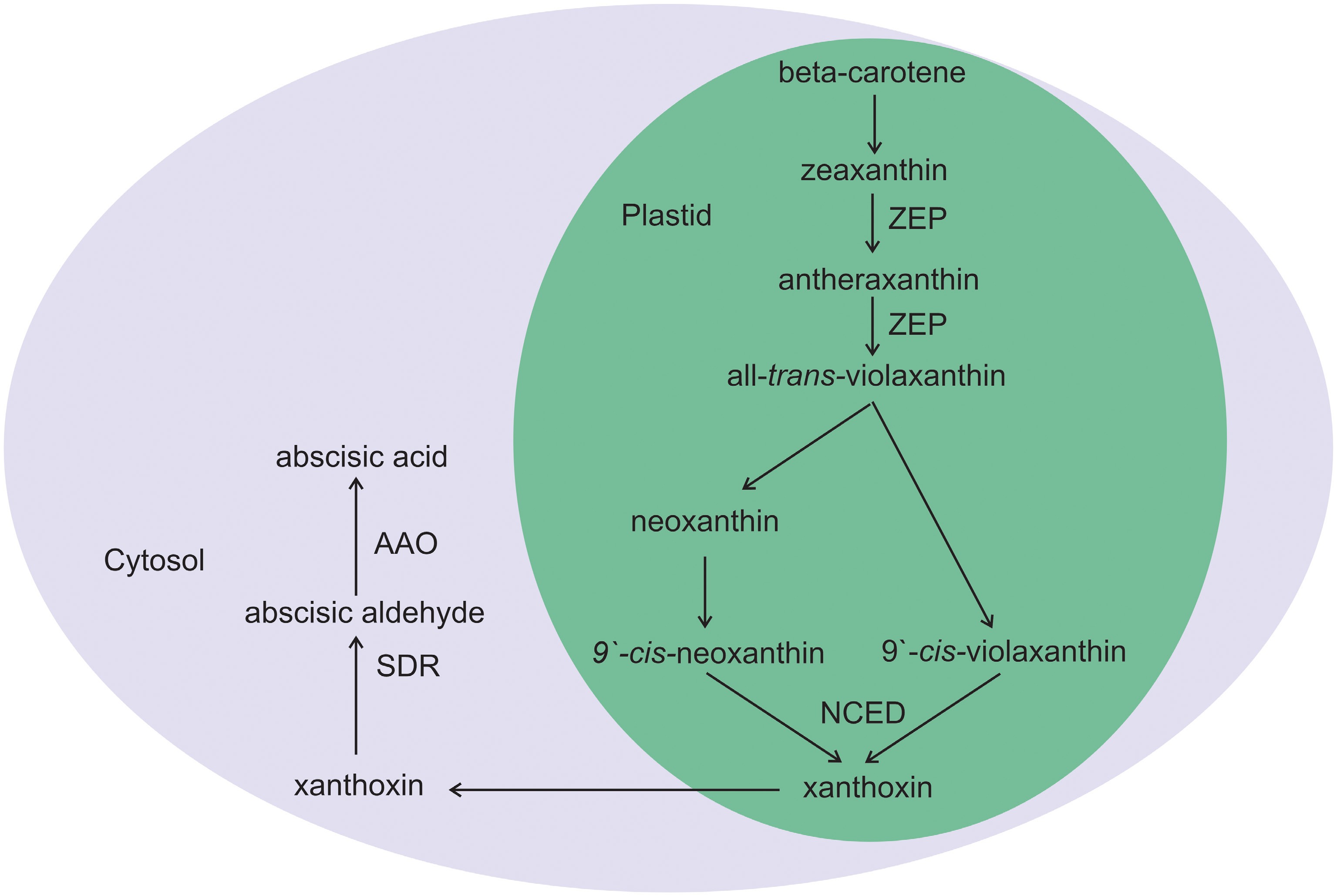

ABA, an isoprenoid molecule (a sesquiterpenoid with 15 carbons, C-15), is a derivative of isopentenyl diphosphate[18]. ABA biosynthesis is an enzyme-catalyzed multistep process that occurs in plastids. The precursor of ABA biosynthesis is the production of carotenoids (β-carotenoids). The conversion of zeaxanthin to all-trans-violaxanthin is catalyzed by the zeaxanthin epoxidase (ZEP) enzyme through an intermediate, antheraxanthin. The production of 9'-cis-neoxanthin and 9'-cis-violaxanthin from cis-isomerization of all-trans-violaxanthin involves an unknown isomerase. Thus, cis-isomers of neoxanthin and violaxanthin could be substrates for NCED to generate xanthoxin, which is a key step in ABA biosynthesis in plastids. Finally, xanthoxin is transferred to the cytosol and cleaved into abscisic aldehyde by short-chain alcohol dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR). Finally, abscisic aldehyde oxidation produces ABA via abscisic aldehyde oxidase (AAO) (Fig. 3)[1].

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of ABA biosynthesis in plants. ABA biosynthesis occurs in plastids and involves different steps that are cleaved into xanthoxin derived from beta-carotenoid precursors. Xanthoxin is then exported to the cytosol from the plastid to form the final product ABA through two-step enzymatic catalysis by short-chain alcohol dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR) and abscisic aldehyde oxidase (AAO). Other enzymes involved in ABA biosynthesis are zeaxanthin epoxidase (ZEP) and 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase (NCED), which are located in the plastid.

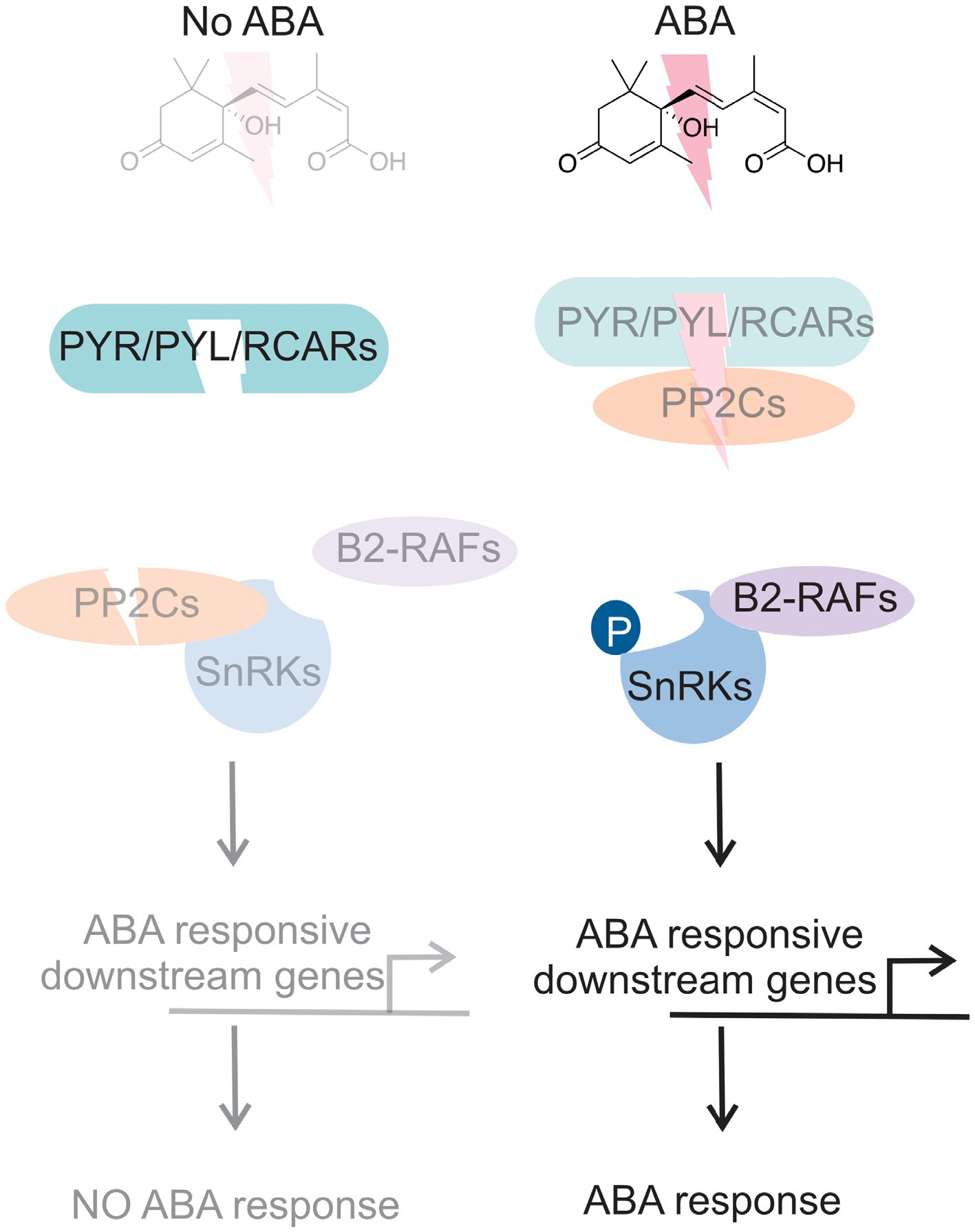

ABA is a primer mediator of stress tolerance in plants. Under suboptimal conditions, ABA production is optimal, and the activity of SnRK proteins and downstream signaling pathways depend on elevated levels of ABA. PP2C protein activation suppresses SnRK protein activity; however, under stressful conditions, when elevated levels of ABA accumulate in a cell or tissue, the activity of PP2C proteins is suppressed by PYR/PYL/RCARs, releasing SnRK proteins. The phosphorylation or autophosphorylation of SnRK proteins by B2-RAFs triggers a cascade of downstream processes, thereby activating ABA signal transduction, gene expression modulation, and other stress tolerance processes (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

ABA signaling model. As shown in the left panel, in the absence of ABA, Pyrabactin Resistance (PYR)/PYR1-like (PYL)/Regulatory Component of ABA Receptor (RCAR) family inactivated to activate ABA receptor proteins, a protein phosphatase 2C (PP2C), to inhibit the activity of subclass III sucrose nonfermenting 1-related protein kinases (SnRK) resulted in no ABA-mediated response. In the presence of ABA, PYR/PYL/RCAR bind to PP2C, releasing SnRKs from inhibition. Auto-activation allows the phosphorylation of downstream ABA-responsive genes, leading to ABA-mediated responses. Light color indicates inactivation, whereas dark color indicates activation.

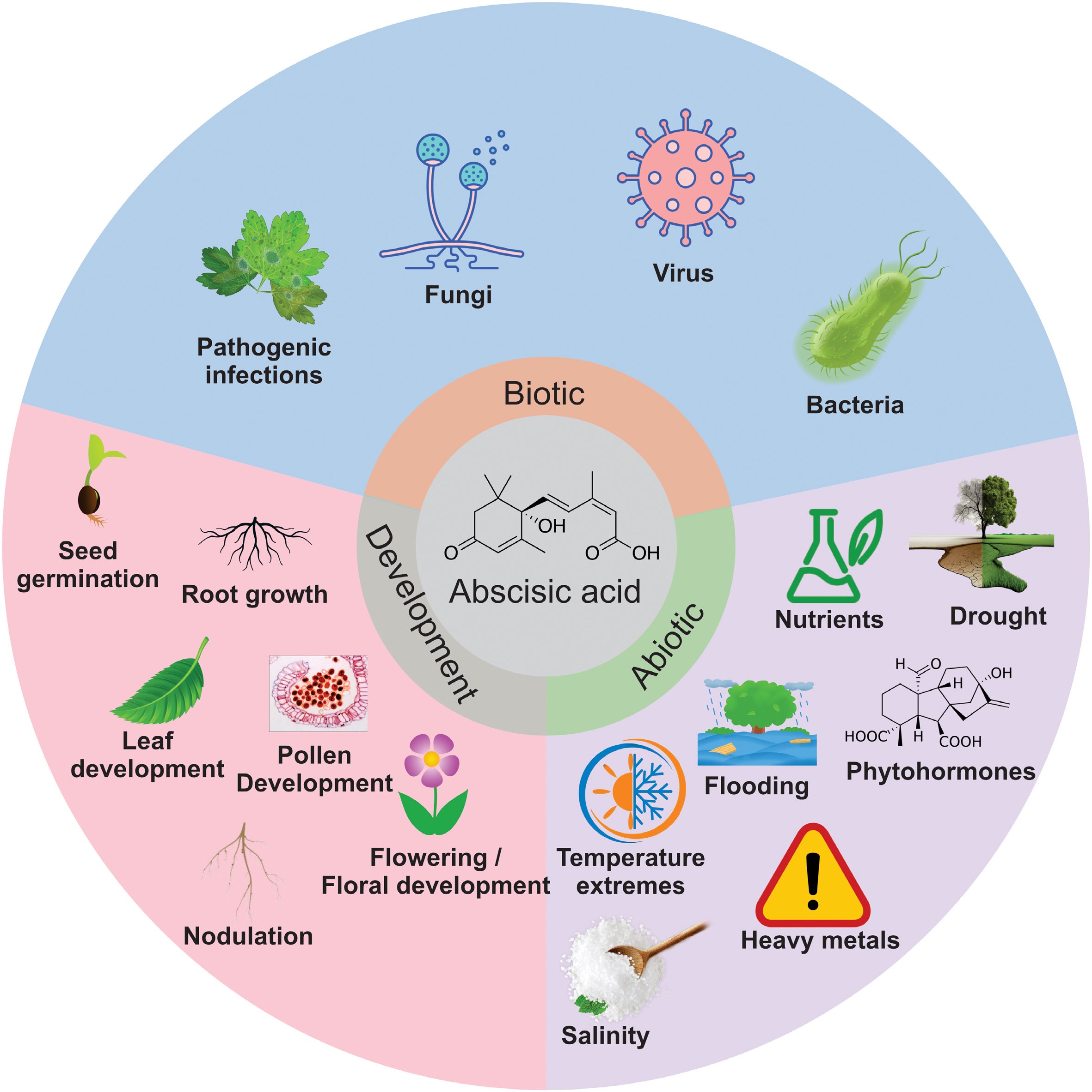

ABA plays a fundamental role in plant biology owing to its indispensable role in plants. In plants, ABA acts as a control player, triggering many physiological and developmental processes such as root system modulation, pollen development, flowering time, and seed germination, and controls plant growth and development by regulating various metabolites[19]. ABA also functions as an endogenous messenger to help plants respond to stress conditions, such as pathogen invasion, salinity, drought, temperature extremes (heat and cold), heavy metals, and nutrient deficiency (Fig. 5)[20]. ABA is an important phytohormone in the field of plant research for the genetic improvement of crops to meet the future demands of the growing population in the era of global climate change.

-

Soil salinity is increasing due to global warming, less annual precipitation, and rising sea levels. Salinity has destructive effects on plant physiology and growth by restricting water absorption from the soil into roots. Additionally, salt stress causes oxidative damage to the membranes by producing large amounts of ROS. ABA regulates salinity stress tolerance; for instance, ABA promotes rice leaf growth under salinity by improving transpiration efficiency[21] and photosynthetic activity, increasing the activities of antioxidant enzymes, and decreasing MDA[22]. Germinating seeds and emerging seedlings are susceptible to various abiotic stresses, including salinity. ABA plays a critical role in regulating seed germination by functioning as a signaling molecule to cope with adverse environmental conditions[19]. Priming maize seeds with ABA confers salinity tolerance by modulating ROS homeostasis, organic acid metabolism, and osmotic adjustment[23].

ABA-mediated stomatal regulation is an important strategy in plant tolerance to salinity stress. In response to salinity, ABA accumulation triggers the activation of SnRK proteins for the phosphorylation of transcription factors with ABA-responsive regulatory elements (ABRE), ABA binding factor (ABF), and ABRE-binding protein (AREB), which regulate stomatal closure in plants[24]. Similarly, in osmotic regulation, ABA-activated SnRK proteins regulate α-AMYLASE3 (AMY3), and BARELY ANY MERISTEM (BAM) 1-dependent production of sugars, which are derived from starch metabolism[25]. The tomato ABA-deficient mutant notabilis harboring a null mutation in NCED1 leads to impaired stomatal regulation under mild to severe salinity stress[26]. Consistent with this, Xiang et al.[27] showed that the chloroplast-localized ABA biosynthesis gene OsNCED4 was significantly induced under salinity stress by ROS homeostasis and regulation of ABA levels. HDA15 overexpression enhances salinity tolerance by increasing the transcription level of NCED3, further enhancing ABA accumulation[28].

Root system architecture is one of the basic components of plants and plays a critical role in plant growth and development, particularly during the seedling stage. ABA plays a biphasic role in root development depending on ABA concentration, but at an optimal level, salinity inhibits root growth. Salinity stress induces ABA accumulation in roots and is required for ABA-mediated root growth. Huang et al.[29] demonstrated that ABA is essential for salt-modulated root growth and salt stress inhibits root elongations but promotes primary root swelling. In contrast, ABA specifically accumulates in response to salinity and high light stress in Arabidopsis[30].

ABA acts synergistically with other phytohormones and growth regulators, such as auxin, gibberellin, cytokines, and melatonin, to control critical processes of plant tolerance to salinity stress. ABA-melatonin synergistically effects were reported by Zahedi et al.[31], where they showed that foliar application of melatonin attributed to enhanced accumulation of ABA in strawberry resulted in higher tolerance to salinity. Exogenous application of SA protects plants from the adverse effects of salinity by promoting plant growth. The effects of SA include the accumulation of Na+ and an increase in the Na+/K+ ratio, enhanced activities of antioxidant enzymes, reduced ABA accumulation, and increased GA content[32].

Auxin is another hormone that exhibits an antagonistic relationship with ABA during salinity stress. Auxin-mediated root development is suppressed by ABA under abiotic stress conditions through activation of ABI5, which suppresses PIN2 proteins. SALT and ABA RESPONSE ERF 1 (OsSAE1) regulate salinity tolerance in rice seedlings through the inactivation of ABI5[33]. Zörb et al.[34] reported the accumulation of ABA in leaves of salt-resistant maize while significant amount of auxin accumulates in roots, together involved in salt resistance.

-

In plants, ABA is synthesized in the leaves and is transported to various cellular entities as per requirement through many transporters. Active transport of ABA relies on ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters, which function as both ABA exporters and importers. ABC proteins are classified into eight major groups, reflecting their evolutionary significance in terms of structural features and functional diversity. The G subfamily (ABCG) is the largest known subfamily of ABC proteins[35]. For instance, several ABA exporters in Arabidopsis, AtABCG25 and AtABCG31, burclover MtABCG20, and ABA importers in Arabidopsis include AtABCG30 and AtABCG40[36]. The Arabidopsis ABCG transporter ABCG25 acts as an ABA efflux carrier from vascular tissues and from the endosperm to stomatal guard cells[37]. Overexpression of AtABCG25 reduces transportational water loss from leaves by closing stomata and redirecting ABA to guard cells[38]. In contrast, the AtABCG40 transporter is critical for proper ABA-mediated plant responses, which mainly function in ABA import to stomatal guard cells, while AtABCG31 functions in exporting ABA from the endosperm. The transporters AtABCG30 and AtABCG40 import ABA into the embryo[39,40]. Besides, AtABCG22 along with its homolog AtABCG25, may control ABA efflux[41,42], whereas NRT1/PTR (NPF) and OsPM1 are possibly involved in ABA influx[43]. The gene encoding the ABCG transporter AtDTX50 functions as an importer of ABA[44]. Shohat et al.[45] reported an emerging role for the ABA importer ABA-IMPORTING TRANSPORTER 1.1 (AIT1.1/NPF4.6) in tomatoes. Later, they showed that ait1.1 exhibited partial resistance to ABA, preventing seed germination under saline conditions.

SnRK is a key component of the ABA signaling pathway. In tomato, overexpression of SnRK1 enhances salinity tolerance by modulating plant physiology, such as accumulation of proline and ROS enzymes, reduced MDA content, and transcriptional regulation of ABA receptors SlPP2C37, SlPYL4, and SlPYL8, which further improves ABA biosynthesis[46]. Wen et al.[47] reported that WD40 domain-containing proteins play diverse roles in plant adaptation to harsh environmental situations. Overexpression of the WD40 repeat-containing gene OsABT enhances root ion exchange activity (Na/K homeostasis), inhibits ROS accumulation, and enhances ABA content. OsABT interacts with ABA receptors, such as OsABIL2, OsPYL4, and OsPYL10, thereby affecting ABA accumulation in plants. In plants, Clade A type PP2C (PP2CAs) are the core regulatory factors of the ABA signaling pathway. For example, rice nuclear-localized OsPP2C68 acts as a negative regulator of the rice ABA signaling pathway under salt stress, thereby regulating ABA-mediated stomatal movements. OsPP2C68 expressed in seeds and Ospp2c68 mutants are sensitive to ABA[48].

In apples, MdMYB44-like significantly induces salinity tolerance via the MdPYL8-MdPP2CA module in the presence of ABA[49]. AtbHLH122 is induced by abscisic acid and salt stress. Transgenic Arabidopsis overexpressing AtbHLH122 displayed enhanced salinity tolerance, proline accumulation, and enhanced ROS enzyme activity[50]. In rice, a short-chain dehydrogenase protein encoded by bHLH110 is pivotal for ABA-mediated salt tolerance by inducing the phosphorylation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase OsMPK1[51]. Heterologous expression of salt-responsive MfbHLH38 from Myrothamnus flabellifolia in transgenic Arabidopsis confers tolerance to salinity stress by ABA-mediated stomatal movement to prevent transpiration water loss. MfbHLH38 transgenic Arabidopsis exhibited enhanced activities of key enzymes participating in ROS scavenging, enhanced soluble sugar content, and higher ABA accumulation[52]. Various genes and proteins involved in ABA-mediated salinity tolerance in different plant species are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Genes involved in ABA-mediated salinity tolerance in various plants.

Plant Gene/protein/

transporterBiological function Ref. Rice ABIL2 and SAPK10 Enhance ABA-signaling for ABA accumulation under salinity stress [29] NAC016 ABA-mediated salinity tolerance [53] WRKY50 As transcriptional repressor of NCED5 and mediated ABA-dependent seedling germination [54] bHLH38 ABA-dependent salt tolerance [55] ERF922 Induce ABA-signaling under salinity stress [56] ASR6 ASR6 interact with NCED1 to enhance ABA accumulation to improve salt and oxidative injuries caused [57] ATAF1 Elevated ABA levels enhance salinity tolerance [58] bZIP42 ABA-responsive Rab16 and LEA genes to confer stress tolerance [59] NAC3 Salinity tolerance [60] ABF2 Positive regulator of ABA-signaling under salt stress [61] bZIP23 Confers ABA sensitivity and salinity tolerance [62] Arabidopsis USP17 Salinity tolerance [63] SDH Decreased ABA sensitivity [64] bZIP36/37/38 ABA dependent salinity tolerance [65] NADK2 Regulator of ABA-mediated stomatal closure, [66] Apple DREB1 ABA dependent and independent salt tolerance [67] Cotton PLATZ1 Reduced salinity tolerance [68] WRKY6-like ABA-mediated salt tolerance and activation of ROS enzymes [69] WRKY17 Activate ABA-signaling and alteration of ROS production [70] Tomato AITR3 ABA-mediated salinity tolerance [71] bHLH22 Salinity tolerance [72] Grapes bHLH1 Salinity tolerance by ABA induced ROS scavenging and osmotic balance [73] Wheat CHP ABA-mediated downregulation enhances salt tolerance [74] Pongamia AITR1 ABA-mediated Salt tolerance [75] -

Salinity stress impairs plant growth, development, and productivity, thereby threatening global food security. The development of salt stress-tolerant or salt-resilient crops is an essential strategy for sustainable crop production. Plants have evolved many adaptive strategies to cope with salinity stress at physiological and molecular levels. However, the mechanisms underlying salinity stress escape are important in plant stress biology. ABA is a key regulator of abiotic stress tolerance, particularly that of salinity. Research on ABA-mediated salinity stress tolerance is still in its infancy in terms of plant development, growth, and tolerance. Furthermore, identification and functional characterization of salt-responsive genes, integrated with the potential application of gene editing in salt research, opens new horizons for future research.

Many critical challenges require attention to enhance our understanding of the regulation of salinity-stress signaling. First, the identification or in-depth exploration of the mechanism of salinity signaling initiation and perception is required to better understand how plants respond to salinity. Second, the synergistic role of ABA with other phytohormones, such as GA, IAA, and JA in salinity stress requires further exploration. Finally, the interactions and regulatory networks within downstream signaling pathways require further investigation.

This work was supported by grants from the China NSFC Research Fund for International Young Scientists (Grant No. 32250410291), the Key Research Program of Hainan Province (Grant No. ZDYF2022XDNY185), and a Special Project for the Academician Team Innovation Center of Hainan Province (Grant No. YSPTZX202206).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualization: Basharat S, Waseem M; writing-original draft preparation: Basharat S, Saeed W, Waseem M; writing-review and editing: Basharat S, Saeed W, Waseem M, Liu P; funding acquisition, supervision: Waseem M, Liu P. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Sana Basharat, Wajid Saeed

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Chongqing University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Basharat S, Saeed W, Liu P, Waseem M. 2025. Abscisic acid mediated salinity stress tolerance in crops. Plant Hormones 1: e015 doi: 10.48130/ph-0025-0014

Abscisic acid mediated salinity stress tolerance in crops

- Received: 12 April 2025

- Revised: 10 May 2025

- Accepted: 03 June 2025

- Published online: 04 August 2025

Abstract: The primary objectives of the development of salt-resilient crops are to investigate, comprehend, and devise strategies to explore the mechanisms of salinity stress. Soil salinity is a major factor limiting plant growth as it induces ion toxicity and nutrient imbalance. Abscisic acid (ABA) is a crucial phytohormone that plays a central role in abiotic stress tolerance, particularly in response to salinity. In this review, we aimed to provide a comprehensive overview of the mechanisms activated by salinity, such as ABA perception and salinity response genes, to modify salinity stress responses. Furthermore, we sought to understand the synergistic role of salt-ABA and other phytohormones in the development of salt-tolerant crops by integrating various biotechnological approaches.

-

Key words:

- Salt /

- Mechanism /

- ROS /

- Pathway /

- Phytohormones