-

Terrestrial plant root systems establish complex symbiotic relationships with microbial communities, which are essential for promoting plant growth, development, and overall health[1]. Studies have shown that microorganisms facilitate nutrient acquisition, thereby benefiting plant growth and development[2,3]. Additionally, rhizosphere microbes are believed to enhance the plant's ability to adapt to environmental stress through various mechanism while also inhibiting pathogen invasion[4,5]. These findings indicate that the rhizosphere microbial community plays a critical role in plant health and development, significantly enhancing crop productivity in agriculture[6].

Fertilization, one of the most prevalent agricultural management strategies, can rapidly alter the physicochemical properties of farmland soil and directly influence the rhizosphere microbial community[7]. The application of chemical fertilizers is essential for maintaining soil fertility and improving crop productivity[8], and rational fertilizer use is crucial for sustainable agriculture. Understanding the microbial community's response to fertilizer application is important for leveraging beneficial microorganisms to promote crop growth and improve crop quality, as well as for fostering environmentally friendly agricultural practices. Potassium (K) is an essential macronutrient for plant growth and development. The supplementation of K fertilizers enhances crop productivity by promoting water absorption, nutrient uptake, and enhancing plant stress tolerance[9], which in turn increases photosynthetic efficiency and promotes plant growth[10].

Sugarcane is an asexual reproducing grass species that is primarily grown in tropical and subtropical regions and serves as the main raw material for sugar production[11]. The high yield of sugarcane is partly attributed to breeding efforts, while agronomic practices also play a crucial role. Among these, fertilizer application is an important measure for enhancing yield[12]. Sugarcane is a K-loving crop[13], and the supplementation of K fertilizer enhances both sugar accumulation[14,15] and drought resistance[16,17]. However, excessive application of K fertilizer can negatively impact crop yield and quality by inhibiting the absorption of other nutrients such as essential nitrogen, magnesium, and iron, ultimately adversely affecting plant growth and development[18]. Therefore, the application of potassium fertilizer needs to be maintained within a reasonable range. Based on previous research[13], an application rate of 150 kilograms per hectare (kg/hm2) may represent the optimal effect of potassium fertilization. Currently, research on K acquisition in sugarcane is relatively limited compared to studies on nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) uptake[19]. Furthermore, the interactions between microbes and sugarcane, as well as the influence of K fertilizer application on microbial colonization in sugarcane roots, remain unclear[20].

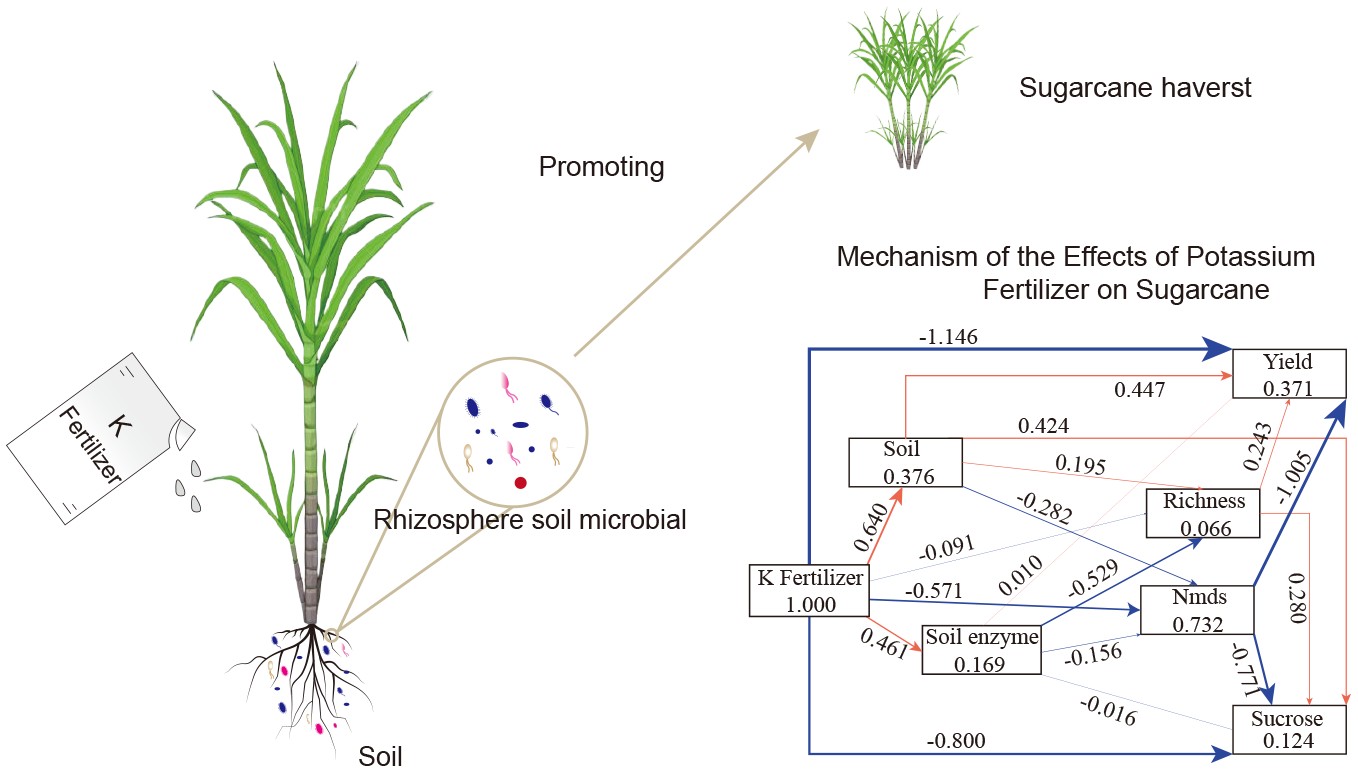

In the present study, it is hypothesized that potassium application enhances the rhizosphere microbial community and promotes sugarcane yield. A field control experiment was conducted to evaluate the rhizosphere microbial community at the seedling stage following K fertilizer application. The relationships between the structure of the rhizosphere microbial community and K fertilizer application were explored, and a model was developed to reveal the correlation between microbial community structure, soil nutrients, and sugarcane yield. These findings are expected to deepen understanding of the feedback regulation mechanisms between the rhizosphere microbial community structure and K application in sugarcane cultivation, assisting in the exploitation of beneficial interactions between crop root systems and rhizosphere microbes, thereby improving soil nutrient absorption and utilization efficiency in crops.

-

A field experiment involving continuous sugarcane cultivation for three years with the same fertilization measures was established at the Sugarcane Research Institute of the Yunnan Academy of Agricultural Sciences (location: 23.70° N, 103.25° E; Altitude: 1,051.80 m), Yunnan Province, China. The YZ19-60 sugarcane variety was planted in March 2020 and cultivated for three years, including new planting, ratoon first year, and ratoon second year. The sugarcane was planted at a depth of 30 cm with a row spacing of 1.1 m, utilizing seed stems, each containing three buds, to ensure a minimum of 120,000 buds per hectare. Fertilizer was applied around the sugarcane seed buds and subsequently covered with soil. The experiment followed a completely randomized design with five K treatments along a gradient (CK: 0 kg/hm2; K1: 75 kg/hm2; K2: 150 kg/hm2; K3: 225 kg/hm2; K4: 300 kg/hm2). The same amounts of N (675 kg/hm2) and P (900 kg/hm2) fertilizers were applied as base fertilizers in the plots. The application rates, based on previous research[13], included a standard rate of 150 kg K2O per hectare. The N fertilizer primarily consisted of urea (46.4% N content), the P fertilizer mainly comprised calcium and magnesium phosphate (P2O5, content 16%), and the potassium fertilizer used was primarily potassium sulfate (K2SO4), containing 50% K2O as the active ingredient. In February 2021 and 2022, during the sugarcane harvest, the stalks were cut, and the ratoon root was kept in the field, marking the planting as Ratoon1 and Ratoon2. Following the emergence of sugarcane seedlings through the soil in March 2021 and 2022, the same amount of fertilizer applied in the previous year for the new sugarcane planting was reapplied, and field management was conducted. The experiment was conducted using a completely randomized design with five replicates. The planting area was evenly divided into five small plots, each covering an area of 100 m2 (10 m × 10 m). Each small plot was further subdivided into five treatment plots, with K fertilizer randomly applied to one of these treatment plots.

Sample collection

-

Sampling was conducted in Ratoon2 when the sugarcane entered the tillering stage, which occurred in mid-May 2022. Three representative plants from each treatment were selected for rhizosphere soil collection. Rhizosphere soil samples were collected from three representative sugarcane plants per treatment. After gently shaking to remove loosely attached soil, the soil tightly adhering to the roots was carefully brushed off and collected as rhizosphere soil. After removing large stones and impurities, the soil samples were mixed evenly, and then approximately 5 g was placed in a sterile centrifuge tube for microbial structure determination. In addition, approximately 1 kg of soil was collected from the cultivated layer (0–30 cm) around each corresponding plant, and 1.5 kg of mixed soil was taken for the determination of soil physicochemical properties after uniform mixing. At the harvest stage in December, sugarcane yield was assessed by harvesting all aboveground parts of each plot. Sugarcane yield was determined by weighing the stalks immediately after cutting, with leaf blades and the immature top portions removed, following standard agronomic procedures to ensure consistency across treatments. For each plot, three representative plants were used to calculate the sucrose content, which was determined using the standard Brix method by extracting juice from the middle internodes of each stalk.

Soil treatment and index detection

-

After removing visible plant residues, stones, and other impurities, the samples were prepared and analyzed for physicochemical properties following the standard procedures described by Bao[21]. Soil pH was determined using the potentiometric method with a soil-to-water ratio of 1:2.5. Soil organic matter (SOM) was determined using the potassium dichromate heating method. Soil total N (TN) was measured using the semi micro-Kjeldahl method, total P (TP) was determined using the molybdenum antimony anti-colorimetric method, while total K (TK) was determined using flame photometry. Available N (AN) was assessed using the alkaline hydrolysis diffusion method, available P (AP) was determined using carbonate-bicarbonate extraction followed by the spectrophotometric method, and available K (AK) was measured using ammonium acetate extraction followed by flame photometry. Soil enzyme activity including catalase (CAT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), urease (Ure), and sucrose (SSC), was evaluated using enzyme activity assay kits from Beijing Boxbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Microbial DNA extraction, amplicon sequencing and analysis

-

Genomic DNA was extracted from 0.3 g of each well-homogenized sample using the MoBio Power Soil® DNA extraction kit (MoBio Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and assessed for purity with a NanoDrop 2000c (Thermo Scientific, USA), involving a total of 20 samples. The V3–V4 hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA bacterial genes were subsequently amplified using primers 338 F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′) and 806 R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′), and the ITS regions of the fungal genes were amplified using primers ITS1F (5'-CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGTAA-3') and ITS2R (5'-GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC-3'). The amplified sequences were used for the construction of clone libraries prior to sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) at Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). The amplification system consisted of a 10-μL PCR reaction system, including 5 μL of KOD FX Neo Buffer, 2 μL of 2.5 mM dNTPs, 0.3 μL of each forward and reverse primer (10 μM), 0.2 μL of high-fidelity DNA polymerase (2.5 U/μL), 30 ng of genomic DNA, and ddH2O added to a final volume of 10 μL. The minimum cycle number was initially determined in a preliminary experiment, and the final PCR amplification program was set as follows: 95 °C for 5 min; 95 °C for 30 s, 50 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 40 s, 29 cycles; 72 °C for 7 min, and conservation at 4 °C, with three replicates for each sample.

The AxyPrep DNA Gel Recovery Kit (Axygen Biosciences, Union City, USA) was used to recover and purify the PCR products, which were confirmed by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis, and the recovered products were quantified using a Quantus fluorescence spectrophotometer (Promega, Wisconsin, USA). The NEXTFLEX Rapid DNA-Seq Kit was used for library construction, and high-throughput sequencing was conducted using the Illumina Miseq PE300 sequencing platform. The dada2 denoising method was employed to correct the high-throughput sequences of the 16S-specific region, while species annotation of amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) was conducted using sklearn (Naive Bayes). The resulting quality-trimmed high-quality reads were then aligned against the SILVA database v.115[22], and pre-clustered at 2% to eliminate sequences with potential errors. Chimeras were identified and removed using UCHIME[23]. The representative sequences and relative abundances of each sample's ASVs were obtained. Based on the denoising results, bacterial diversity analysis was performed to extract bacterial community structure and interactions between bacteria and physicochemical indicators in the high-throughput sequencing samples. Detailed methodologies for PCR amplification, library preparation, and raw data preprocessing were available in a previous study[24].

Statistical analysis

-

In the present study, data entry and storage were conducted using MS Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA). For data analysis and visualization, R 4.1.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), IBM SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and Smart-PLS 4.0 (SmartPLS GmbH, Oststeinbek, Germany) were employed. One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to test for differences in soil physicochemical properties, microbial community structure, and soil enzyme activity data. Principal Co-ordinates Analysis (PCoA) was applied to examine the similarities or differences in the rhizosphere microbial community structure, while Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance (PERMANOVA) was used to assess community differences. Additionally, Linear Discriminant Analysis Effect Size (LEfSe) was used to identify high-dimensional biomarkers and reveal genomic characteristics, including genes, metabolism, and classification. The Mantel test and Redundancy Analysis (RDA) were conducted to evaluate correlations between microbial community structure and soil factors. Before model construction, stepwise regression analysis was performed to simplify the model and achieve a parsimonious outcome. Variance Partitioning Analysis (VPA) was used to evaluate the effects of soil physicochemical factors and soil enzyme activity on microbial community structure. Furthermore, hierarchical partitioning was used to evaluate the explanatory power of individual environmental factors[25]. Finally, Partial Least Squares Path Modeling (PLS-PM) was used to evaluate the contribution of K application to soil properties, soil enzyme activity, and the rhizosphere microbial community structure in sugarcane.

-

To explore the impact of K application on sugarcane harvest yield, the sugarcane yield and sucrose content were collected in this study. The results showed that sugarcane yield increased with the application of potassium fertilizer, reaching a maximum at the K2 treatment (150 kg/hm2); however, further increases in potassium levels (K3 and K4) led to a decline in yield (Fig. 1a). A similar trend was observed for sucrose content, which peaked at the K2 level and decreased at higher potassium application rates (Fig. 1b). These findings suggested that moderate K application (K2) optimized both sugarcane yield and sucrose content, while excessive or insufficient potassium application might reduce productivity and quality.

Figure 1.

Comparative analysis of yield and sucrose content across five different K application levels (K1–K5). (a) The log-transformed yield (kg/hm2) at varying K application levels. Data points represent the mean ± standard error (SE), lowercase letters represent significant differences indicated by different K application levels. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey's test. (b) The sugarcane sucrose under the five different K application levels.

Rhizosphere microbial community profiles were distinct in different K application levels

-

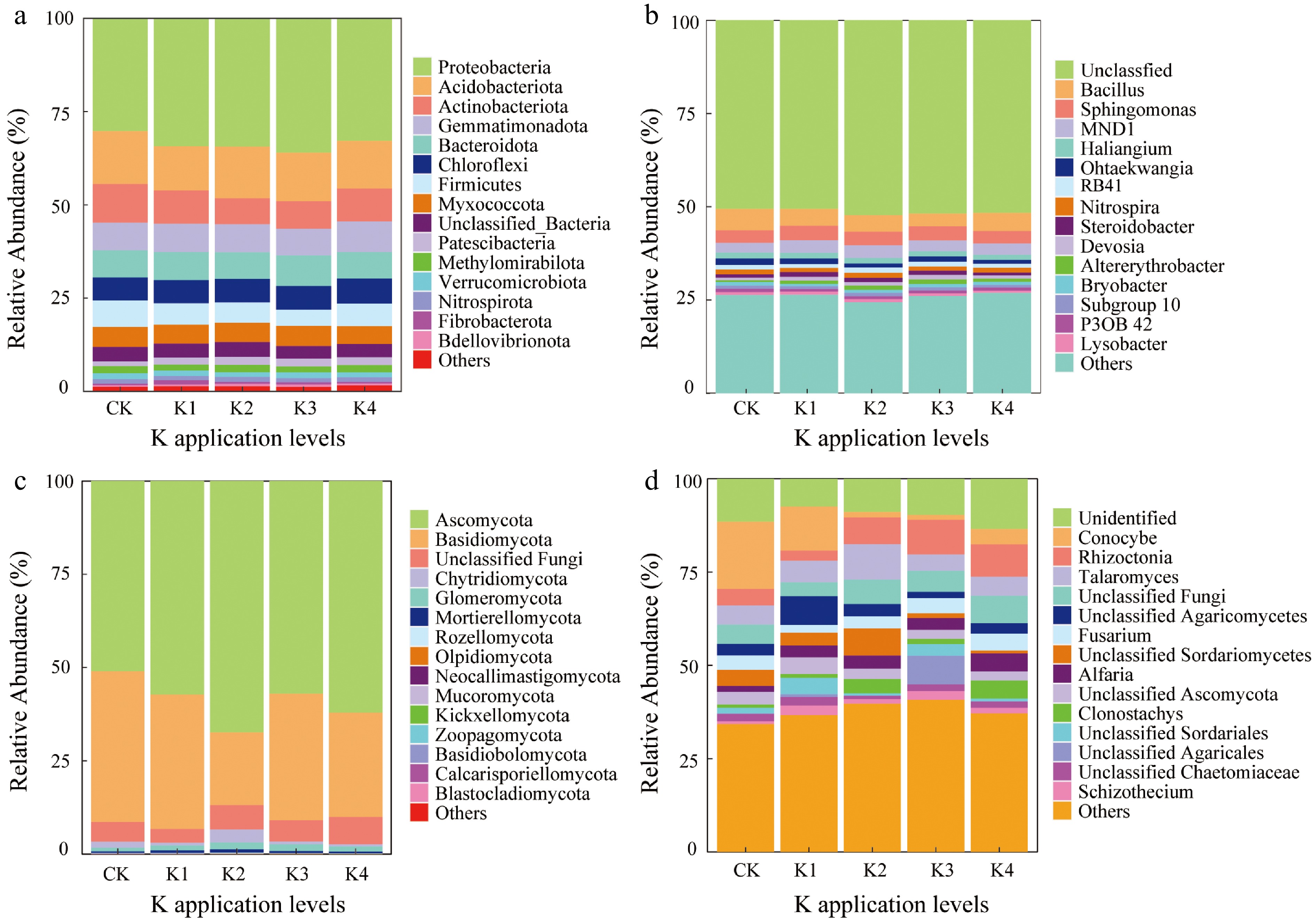

The microbial community composition showed significant changes under different potassium application levels. In the bacterial phylum levels (Fig. 2a), Proteobacteria consistently dominated, with little variation in relative abundance across treatments. However, the relative abundance of Acidobacteria and Actinobacteria decreased at higher potassium levels (K3, K4). Bacteroidota and Chloroflexi exhibited some variation at higher potassium application rates. At the genus levels (Fig. 2b), Sphingomonas, MND1, and Halangium were abundant across all treatments, with Sphingomonas showing an increase at higher potassium levels. At the fungal phylum levels (Fig. 2c), Ascomycota dominated, with no significant changes in relative abundance across potassium treatments, indicating that potassium application had minimal impact on this phylum. In contrast, the relative abundance of Basidiomycota and Chytridiomycota was decreased, especially in the K3 and K4 treatments, suggesting that potassium may suppress these fungal groups. At the fungal genus levels (Fig. 2d), Conocybe and Rhizoctonia showed significant increases in relative abundance in the K3 and K4 treatments, implying that potassium fertilization may promote the growth of these genera. Overall, these findings demonstrate that potassium fertilization significantly influences the soil microbial community composition; potassium application promotes the growth of certain bacterial and fungal genera while inhibiting others, thus affecting the microbial community composition.

Figure 2.

Relative abundance of the top 15 microbial communities at different taxonomic levels across five different K application levels. (a), (b) Bacterial and fungal community composition at the phylum and genus level, respectively. (c), (d) Fungal community composition at the phylum and genus level, respectively. 'Others' represented the sum of low abundance taxa.

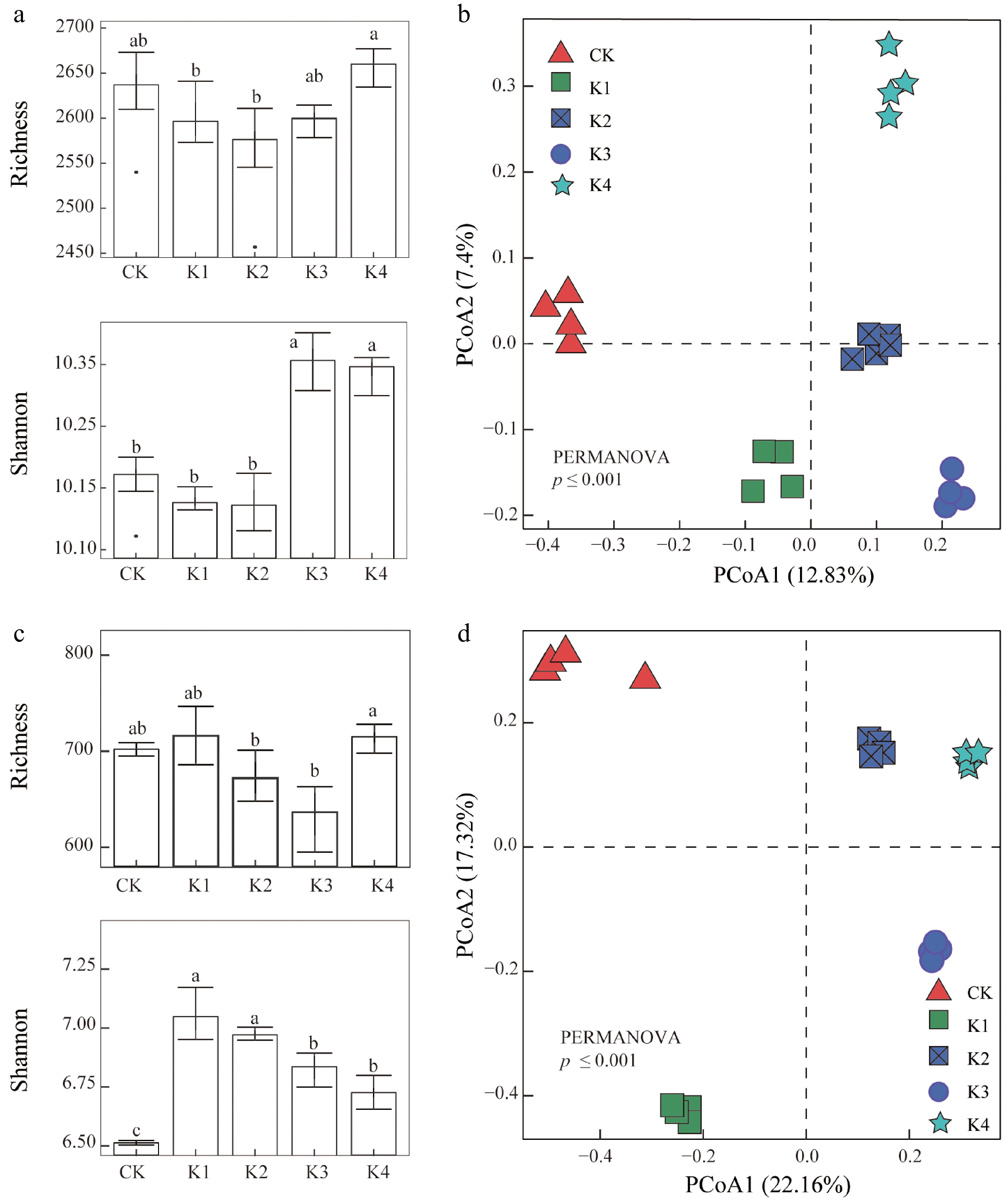

The diversity of the rhizosphere bacterial community diversity, as indicated by the richness index, Shannon index, and Simpson index, significantly changed following K fertilizer application. Low K fertilizer application rates (0−225 kg/hm2) resulted in a decrease in microbial diversity, whereas higher levels of K fertilizer led to an increase in diversity (Fig. 3a). Furthermore, the PCoA (β-diversity) based on Bray-Curtis distance demonstrated clear separation in diversity among different K levels (Fig. 3b), with PERMANOVA results indicating that the diversity of soil rhizosphere bacterial was significantly affected by K fertilizer application. The overall fungal diversity decreased with K application compared to the control; however, a higher K application rate enhanced fungal diversity (Fig. 3c). The PCoA (β-diversity) based on Bray-Curtis distances showed distinct separations among different K treatments concerning the fungal community structure (Fig. 3d). In addition, PERMANOVA results showed that the soil rhizosphere fungal community was significantly influenced by the K application rate. These results indicated that the fungal community structure within the sugarcane rhizosphere was altered by K application.

Figure 3.

The alpha and beta diversity of microbial communities across five different K application levels. (a), (b) Show bacterial richness and Shannon diversity index, with significant differences indicated by different lowercase letters (p < 0.05). (c), (d) Show fungal richness and Shannon diversity index, with similar statistical annotations. (e), (f) Display PCoA plots based on bacterial and fungal community composition using Bray-Curtis dissimilarity, with significant differences in microbial community structure identified by PERMANOVA.

Microbial biomarkers in sugarcane rhizosphere microbial community

-

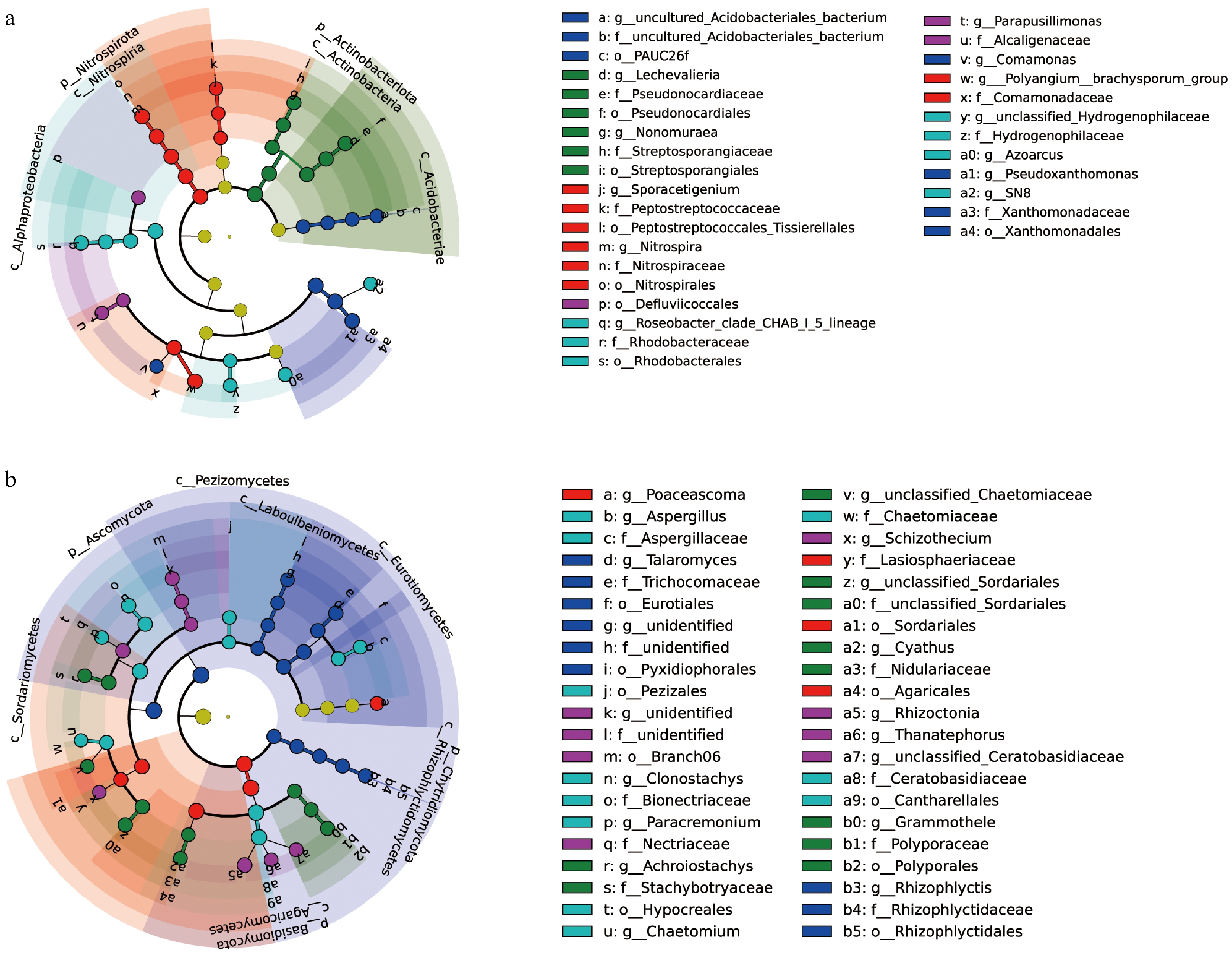

LEfSe determines the features that most likely explain differences between classes by coupling standard statistical significance tests with additional assessments that encode biological consistency and effect relevance. It was performed to evaluate differences in microbial community structure across various K treatments. Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) scores greater than four indicated the identification of a microbial biomarker in the sugarcane rhizosphere. According to the cladogram (Fig. 4a), microbial community biomarkers were enriched under different K application rates. These biomarkers predominantly belonged to Proteobacteria, Acidobacteriota, Actinobacteriota, Nitrospirota, and Firmicutes at the phylum level. The fungal cladogram (Fig. 4b) revealed significant differences in microbial community structure under varying K application rates, highlighting the critical role of K application rates in microorganism selection within sugarcane fields. The major fungal biomarkers were primarily classified into Basidiomycota, Ascomycota, and Chytridiomycota.

Figure 4.

LEfSe analysis of samples is shown. (a), (b) Display the LDA scores (log10) for differentially enriched bacterial and fungal taxa across five different K application levels. Higher LDA scores indicate a greater contribution to group differences. Each node represents a taxon, with node size reflecting abundance, and colors represent different bacterial/fungal phyla.

Soil properties and enzyme activity shaped microbial community structure

-

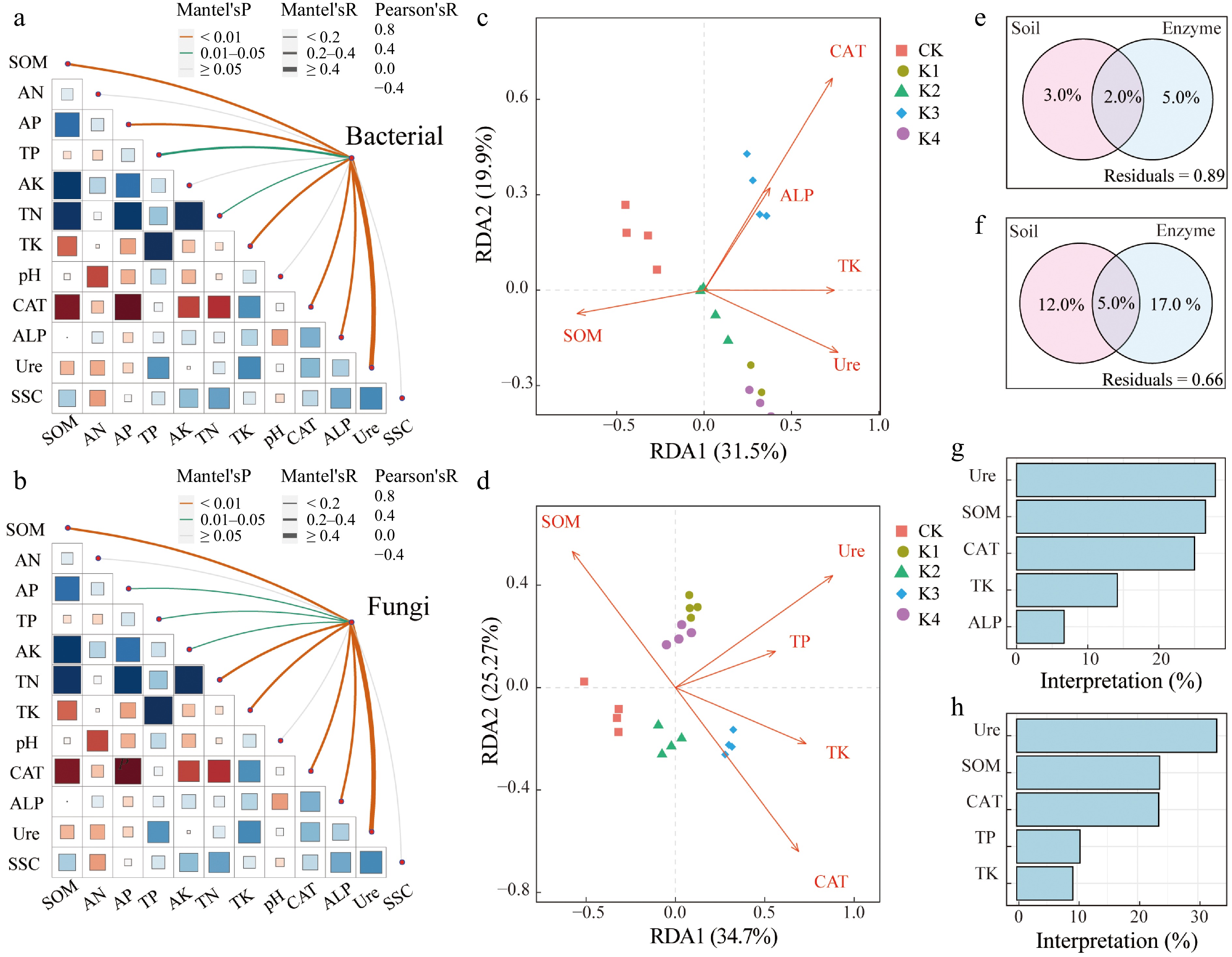

The Mantel test results indicated a significant correlation between bacterial community structure and both soil properties and enzyme activity within the sugarcane root rhizosphere (Fig. 5a). Specifically, SOM, soil AP, soil TK, soil CAT, ALP, and Ure activity exhibited positive correlations with the bacterial community structure, while soil TP and TN displayed negative correlations. In the case of fungal, the Mantel test results revealed that SOM, TN, TK, CAT, ALP, and Ure activity positively correlated with fungal community structure, while negative correlations were observed with soil AP, TP, and AK in the sugarcane rhizosphere (Fig. 5b). The results showed that K application modified soil properties, which subsequently influenced the microbial community structure in the rhizosphere.

Figure 5.

Relationships between environmental factors and microbial community for bacteria and fungal. (a), (b) Show mantel testing in bacterial and fungal. (c), (d) Represent redundancy analysis (RDA) plots in bacterial and fungal communities, with significant environmental variables. (e), (g) Show variance partitioning analysis diagrams in bacterial and fungal communities. (f), (h) Show hierarchical partitioning analysis in bacterial and fungal communities.

Moreover, Mantel test results showed that soil properties and enzyme activity influence microbial community relative abundance. Bacterial RDA results revealed that axes accounted for 51.4% of the total variation, with axis one (RDA-1) and two (RDA-2) explaining 31.5% and 19.9% of the variation, respectively (Fig. 5c). Significant positive correlations were observed between TK and Ure activity with RDA-1, while SOM exhibited a significant negative correlation with RDA-1. Furthermore, CAT and ALP activities demonstrated significant positive relationships with RDA-2. According to the fungal RDA, the two axes explained 60.0% of the total variation, with axis one (RDA-1) and two (RDA-2) explaining 34.7% and 25.3% of the variation, respectively (Fig. 5d). Soil TK, Ure activity, and TP showed positive correlations with RDA-1, whereas SOM had a significant positive correlation with RDA-2. However, soil ALP activity was negatively correlated with the fungal community structure. These findings indicated that K fertilizer application significantly influenced the microbial community structure in the sugarcane rhizosphere by altering soil properties such as SOM as well as Ure and ALP activity, which in turn shaped the microbial community structure.

Bacterial VPA results showed that soil physicochemical property and soil enzyme activity accounted for 3.0% and 5% of the variation in microbial community structure under K fertilizer supplementation, with both jointly explaining 2.0% of the variation (Fig. 5e). Furthermore, Ure activity and SOM had relatively significant contributions to the microbial community structure. Similarly, fungal VPA results(Fig. 5f) demonstrated that soil physicochemical properties accounted for 12.0% of the variation in the microbial community structure and soil enzyme activity contributed 17.0%, with together accounting for 5.0% of the variation (Fig. 5g). Additionally, hierarchical, VPA and canonical results indicated Ure enzyme activity and SOM significantly influenced microbial community structure (Fig. 5h).

Contributions of soil properties and soil enzyme activity to microbial community structure based on PLS-PM analysis

-

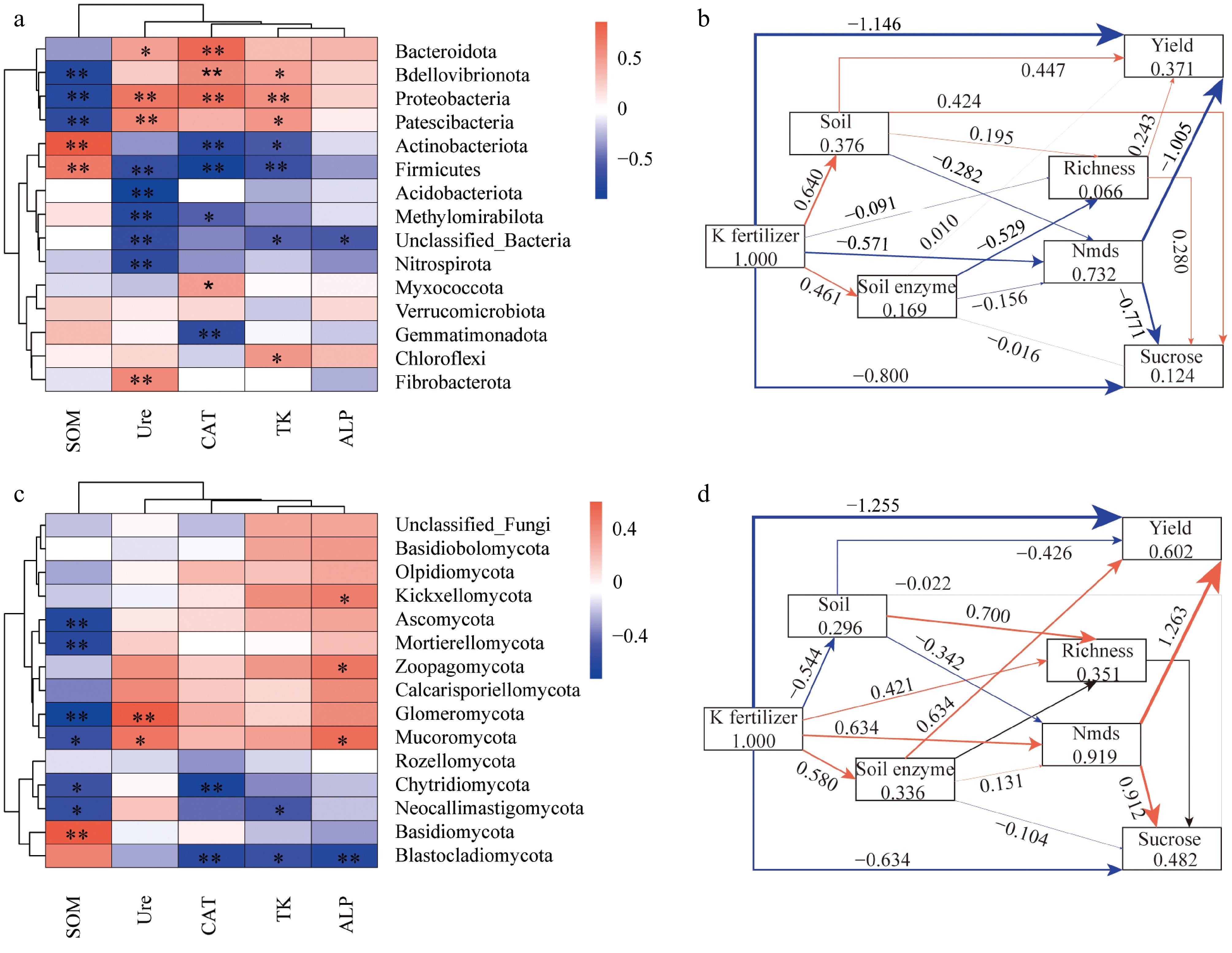

The relationships between microbial phyla, environmental factors, and crop yield were analyzed using correlation heatmaps and structural equation modeling (SEM). The heatmaps (Fig. 6a) revealed significant correlations between specific microbial phyla and environmental factors. For bacterial communities, Bacteroidota, Proteobacteria, and Actinobacteriota demonstrated strong positive correlations with soil organic matter (SOM) and catalase activity (CAT), whereas Nitrospirota and Verrucomicrobiota were negatively correlated with urease activity (Ure). Similarly, fungal communities (Fig. 6b) exhibited positive associations between Ascomycota and CAT, while Basidiomycota was negatively correlated with total potassium (TK).

Figure 6.

Relationships between microbial taxa with environmental factors. (a), (b) Heatmaps display correlations between bacterial and fungal phyla with environmental factors. The color intensity indicates correlation strength, with red for positive and blue for negative correlations. Significant correlations are marked with *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01. (c), (d) Show Partial Least Squares Path Modeling (PLS-PM) illustrating soil properties, microbial richness, and enzymatic activities impact on yield. Arrows indicate significant pathways, with thickness representing relationship strength, and direct/indirect effects on yield are shown in red and blue.

The SEM analysis (Fig. 6c) quantified the direct and indirect effects of soil properties, microbial richness, and enzymatic activities on crop yield. For bacterial communities, soil properties had a direct positive effect on yield (path coefficient = 0.376), mediated by microbial richness and enzymatic activities. Similarly, fungal communities (Fig. 6d) significantly contributed to yield, with richness playing a dominant role (path coefficient = 1.263), while enzymatic activities such as Ure and CAT indirectly influenced crop yield via soil properties. The models explained 37.1% and 60.2% of the total variance in crop yield for bacterial and fungal communities, respectively, indicating a stronger impact of fungal communities on yield enhancement. These results highlighted the critical roles of microbial community composition and soil enzymatic dynamics in regulating crop productivity.

-

Fertilizer application is the most widespread and direct method for improving farmland and soil fertility in agriculture[26]. It significantly alerts soil properties dramatically, with immediate impacts on microbial community structure[27]. Previous studies have reported that N and P fertilizer application significantly influence microbial community diversity, although the effects can be inconsistent. The addition of manure and straw can increase soil bacterial diversity, while the application of mineral N may decrease it[28]. Furthermore, the use of manure alters microbial α-diversity and microbial networks but does not affect microbial β-diversity in irrigation fields, reflecting the inconsistencies associated with fertilizer application[29]. In this study, a clear relationship between the rate of fertilizer application and changes in microbial diversity under different K application levels was not observed (Fig. 3a and c). Initially, K fertilization reduced microbial diversity, but as the application rate increased, microbial diversity also increased. This phenomenon warrants further investigation.

The initial reduction in microbial diversity following K fertilizer application may be related to the changes in microbial groups sensitive to K in the soil. In the early stages of K fertilization, certain microbial groups may not thrive in the rhizosphere, leading to a decrease in microbial diversity[30]. However, once a specific threshold of K application is reached, it not only meets the growth requirements of the crop but also improves soil structure, promoting the proliferation of certain microbial groups[31]. Proper K fertilization may also enhance the metabolic activity of specific soil microorganisms, thereby boosting their functional roles within the soil ecosystem, which ultimately leads to the restoration or even an increase in microbial diversity. This process underscores the importance of finding a balance in fertilizer management. Consequently, future studies should investigate the non-linear relationship between K fertilizer application rates and microbial diversity and explore how precision fertilization practices can contribute to soil health and improve crop productivity.

Microbial community enrichment in response to potassium fertilizer application

-

Fertilizer application is known to significantly alter soil microbial communities, with specific nutrients driving distinct shifts in microbial composition and function[7,32]. In this study, K fertilizer application induced notable changes in microbial biomarkers, as identified by LEfSe analysis (Fig. 4). These alterations in microbial biomarkers were critical, as they directly or indirectly influenced the structure and functional dynamics of soil microbial communities[33,34]. Different fertilizers, such as K and N, provide unique nutrient sources that selectively promote or suppress specific microbial populations, thereby modulating the metabolic activities of soil microorganisms[35]. Such shifts not only affect microbial diversity but are also closely linked to soil nutrient availability, particularly in nutrient cycling and transformation processes, where the functional roles of microbes are pivotal.

Notably, the application of K fertilizer led to significant alterations in the rhizosphere microbial composition of sugarcane. In the present study, it was found that key microbial taxa, including Proteobacteria, Acidobacteriota, Firmicutes, Basidiomycota, and Ascomycota, were enriched in response to K fertilization (Fig. 4a). Proteobacteria, the dominant phylum observed in this study, is well-documented for its roles in soil nutrient recycling and enhancing crop resistance to abiotic stresses[33]. Similarly, Acidobacteriota and Firmicutes, which are associated with pathogen suppression, may contribute to reduced disease incidence and improved plant health. While Basidiomycota and Ascomycota are often recognized as plant pathogens (Fig. 4b), Ascomycota also plays a crucial role in carbon and nitrogen cycling, particularly in arid ecosystems[36]. The enrichment of these microbial taxa following K application suggests their potential involvement in enhancing sugarcane drought resistance[37] and pest and disease resistance. These shifts in the microbial community have profound implications for crop yield. As soil microbial populations adapt to K fertilization, their interactions with plant roots may lead to improved nutrient uptake, enhanced drought resilience, and stronger disease resistance—all of which are critical for optimizing crop yield under challenging environmental conditions. This study highlights the dual role of K fertilizer in shaping microbial community structure and function, ultimately driving improvements in crop performance. Future research should focus on elucidating the causal relationships between specific microbial taxa and crop yield, as well as exploring how tailored fertilization strategies can be designed to harness the beneficial effects of microbial communities for sustainable agriculture.

Potassium fertilizer application directly effects sugarcane harvest yield by soil and microbial community

-

According to the PLS-PM results, K application positively influenced soil properties, soil enzyme activity, and bacterial community structure while showing no significant effect on fungal community structure. Similar findings were observed in a paddy soil study conducted in south China[32]. Some researchers have suggested that long-term inorganic fertilization (NPK, M, NPKM) enhances soil nutrient status, and the combined application of manure and chemical fertilizer (NPK) enhances the concentrations of soil organic carbon, AN, AP, and AK[32]. In the present study, K application altered TN and TP in the sugarcane rhizosphere and enhanced soil enzyme activity. Long-term N and P fertilizer applications have been shown to increase soil nutrient contents, microbial biomass, and extracellular enzyme activity in a paddy soil[38], indicating that prolonged fertilizer application can improve soil microbial community structure.

Moreover, the effects of K application on sugarcane yield and sucrose were evaluated in this study (Fig. 6). It was found that K application did not directly affect sugarcane yield and sucrose content but instead altered soil properties, soil enzyme, and microbial community, which in turn promoted sugarcane yield and sucrose. Previous studies have shown that K application benefits crop harvest[39], but the underlying processes have not been well studied in sugarcane fields. The role of fertilizers in promoting crop harvests was assessed, and the chemical processes influencing sugarcane yield. Although the conclusions are limited, further experiments are needed in future studies.

-

This study utilized a field experiment with continuous sugarcane cultivation to investigate the impact of K fertilizer application on the microbial community structure during the tillering stages of sugarcane. The results demonstrated that K fertilization significantly improved soil physicochemical properties, enhanced soil enzyme activities, and reshaped the structure of the rhizosphere microbial community. Among the treatments, the application rate of 150 kg/hm² showed the most pronounced effects, effectively enhancing soil quality and increasing microbial diversity. The relative abundance of dominant microbial taxa such as Proteobacteria, Acidobacteriota, Actinobacteriota, and Ascomycota increased notably following K application. Furthermore, K fertilization influenced rhizosphere microbial communities by modulating soil environmental factors, thereby directly or indirectly promoting sugarcane yield and sucrose content. These findings highlight that appropriate potassium application improves soil health, optimizes microbial communities, and enhances sugarcane yield and quality.

This work was funded by the Yunnan Revitalization Talents Support Plan. We gratefully acknowledge financial support from Earmarked Fund for China Agriculture Research System (Grant No. CARS-17), Yunnan Agricultural Joint Special Program (Grant No. 202301BD070001-213), Yunnan Fundamental Research Projects (Grant No. 202201AT070285), and the Yunnan Seed Laboratory Program (Grant No. 2022YFD2301100).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: data visualization: Zhang Z, Li R, Yang S, Liu J; writing − draftmanuscript preparation: Zhang Z; investigation: Wang Y, Ai J, Dao J; writing − revision & editing: Deng J, Zhao Y; conceptualization: Deng J, Zhao Y. All authors reviewed the resultsand approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article, and the raw high-throughput sequencing data generated by Illumina platforms have been deposited in the GenBank Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database (Bioproject Accession No. PRJNA1028179).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Received 2 April 2025; Accepted 22 May 2025; Published online 20 August 2025

-

Potassium application modulates the composition and diversity of rhizosphere microbial communities in sugarcane, with 150 kg/hm2 identified as the optimal application rate.

K fertilization significantly enriches specific microbial functional groups, which are closely associated with soil nutrient status.

Microbial communities and soil factors collectively influence sugarcane yield following K application, suggesting that targeted regulation of microbial structure and soil properties can enhance crop productivity.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Hainan University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang Z, Wang Y, Ai J, Dao J, Li R, et al. 2025. The role of K fertilizer in shaping bacterial and fungal communities in the sugarcane rhizosphere. Tropical Plants 4: e028 doi: 10.48130/tp-0025-0020

The role of K fertilizer in shaping bacterial and fungal communities in the sugarcane rhizosphere

- Received: 02 April 2025

- Revised: 05 May 2025

- Accepted: 22 May 2025

- Published online: 20 August 2025

Abstract: The rhizosphere microbial community is significantly influenced by the application of chemical fertilizers, with potassium (K) fertilizer playing a crucial role in enhancing both the yield and quality of sugarcane. However, limited studies have investigated how K fertilizer impacts sugarcane productivity through synergistic interactions between microorganisms and the soil environment. This study aims to explore the regulatory effects of K (K2SO4, 50% K2O) fertilizer on bacterial and fungal communities and to examine the mechanisms linking microbial structure to sugarcane yield. A field experiment was conducted with five levels of K fertilizer to evaluate microbial community structure, soil properties, and enzyme activities that affect sugarcane productivity. The results indicated that K application significantly altered soil properties, with a threshold of 150 kg/hm2 identified, where shifts in both bacterial and fungal diversity were observed. Linear discriminant analysis (LEfSe) revealed changes in the abundance of microbial taxa, including Proteobacteria, Acidobacteriota, Actinobacteriota, and various fungal groups, across different K levels. Redundancy analysis (RDA) demonstrated that soil properties and enzyme activities (e.g., catalase and urease) significantly influenced microbial community structure. Furthermore, partial least squares path modeling analysis (PLS-PM) showed that changes in the microbial community directly affected sugarcane yield. The results of this study indicate that K fertilizer application indirectly enhances sugarcane yield and sucrose content by promoting microbial diversity and soil enzyme activity, ultimately increasing crop productivity. This provides valuable insights into the dual regulatory effects of K fertilizer on rhizosphere bacteria and fungi, emphasizing the key microbial taxa and soil-environment interactions that drive sugarcane productivity and sucrose accumulation.

-

Key words:

- K fertilizer /

- Sugarcane /

- Microbial /

- Rhizosphere