-

Locomotor navigation requires the integration of motor outputs[1−3] and task goals[4−6] with external sensory feedback[7−10] and internal proprioceptive and vestibular information[11,12]. Visual processing is crucial for locomotor control[10,13−15], affecting gait stability[16−18] and enabling reactive step modifications in response to environmental obstacles[19,20]. Gait-related falls are a common injury mechanism for older adults and patients with neurological disorders, costing approximately

${\$} $ Visual information enters the brain through the thalamic projection to the primary visual cortex, processing object recognition via the visual ventral stream[22] and visuospatial properties via the visual dorsal stream. The posterior parietal cortex integrates via the dorsal stream to provide distance estimation[23] and plan limb coordination[24,25] during precision walking and obstacle navigation. The premotor cortex, located at the end of the visual dorsal stream, also receives transformed visual information from the parietal cortex for modifying visually guided movements[26,27]. The neurological basis of visually guided locomotion has mostly been studied in rodents and cats, but there is a need to better understand cortical pathways underlying human locomotor control during realistic behaviors.

Mobile electroencephalography (EEG) has been used to investigate spectral power dynamics during human locomotion[9,28,29]. Although EEG signals can be contaminated by extraneous physiological signals[30] and movement-related artifacts[31], mobile EEG hardware and signal processing advancements[28,29,32,33] have been used to identify electrocortical spectral power fluctuations throughout the gait cycle[28] and various gait speeds[29,34]. Immersive technologies, such as virtual and augmented reality, enable the creation and presentation of fully customizable and experimentally controlled visual environments[35−38]. During locomotor navigation tasks, human subjects have shown similar behavioral outcomes[39] and gaze behaviors[40] in matched virtual and real-world settings. Changing visual scenery has shown changes in the response patterns of the human visual cortex among immobile subjects[41,42], and visual restriction during walking has led to sensorimotor cortical theta (5−8 Hz) and beta band (14−30 Hz) desynchronization, interpreted as greater sensory processing[33].

We aimed to determine the influence of visual environmental complexity and gait speed on human electrocortical spectral power during locomotion. By altering the visual scenery during walking on a treadmill in projected virtual reality at a range of gait speeds, we aimed to uncover neural biomarkers for understanding the human brain's processes during realistic locomotor behaviors. By altering gait speed, we aimed to confirm the effects of gait speed on electrical brain activities and identify interactions between gait speed and visual environmental complexity. We hypothesized that greater visual environmental complexity and gait speed would increase visual and sensorimotor cortical processing, identified by reduced alpha (8−13 Hz) and beta band spectral power (13−30 Hz). These findings can help to determine how human electrical brain dynamics are affected by visual environments among freely moving human subjects. Future comparisons between healthy controls and individuals with gait deficits could help to identify differences in supraspinal neural circuits and pathways for developing neurorehabilitation interventions.

-

Eleven healthy human subjects (6 female, 5 male; mean age 23.8 ± 3.1 years) participated in the study. To achieve 0.8 statistical power, a priori analysis identified a sample size of 10 or more subjects. Inclusion criteria included the ability to walk unassisted and no history of recent falling events, major injury within the past six months, symptoms interfering with walking ability, stroke, chronic pain, medical implants, or an allergy to silver. All experimental protocols adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the institutional review board at Texas A&M University (approval number: IRB2021-1198D). All research activities were conducted in accordance with the guidelines and regulations set forth by the institutional review board. Prior to participation, all participants provided informed consent and permission to publish the information and images.

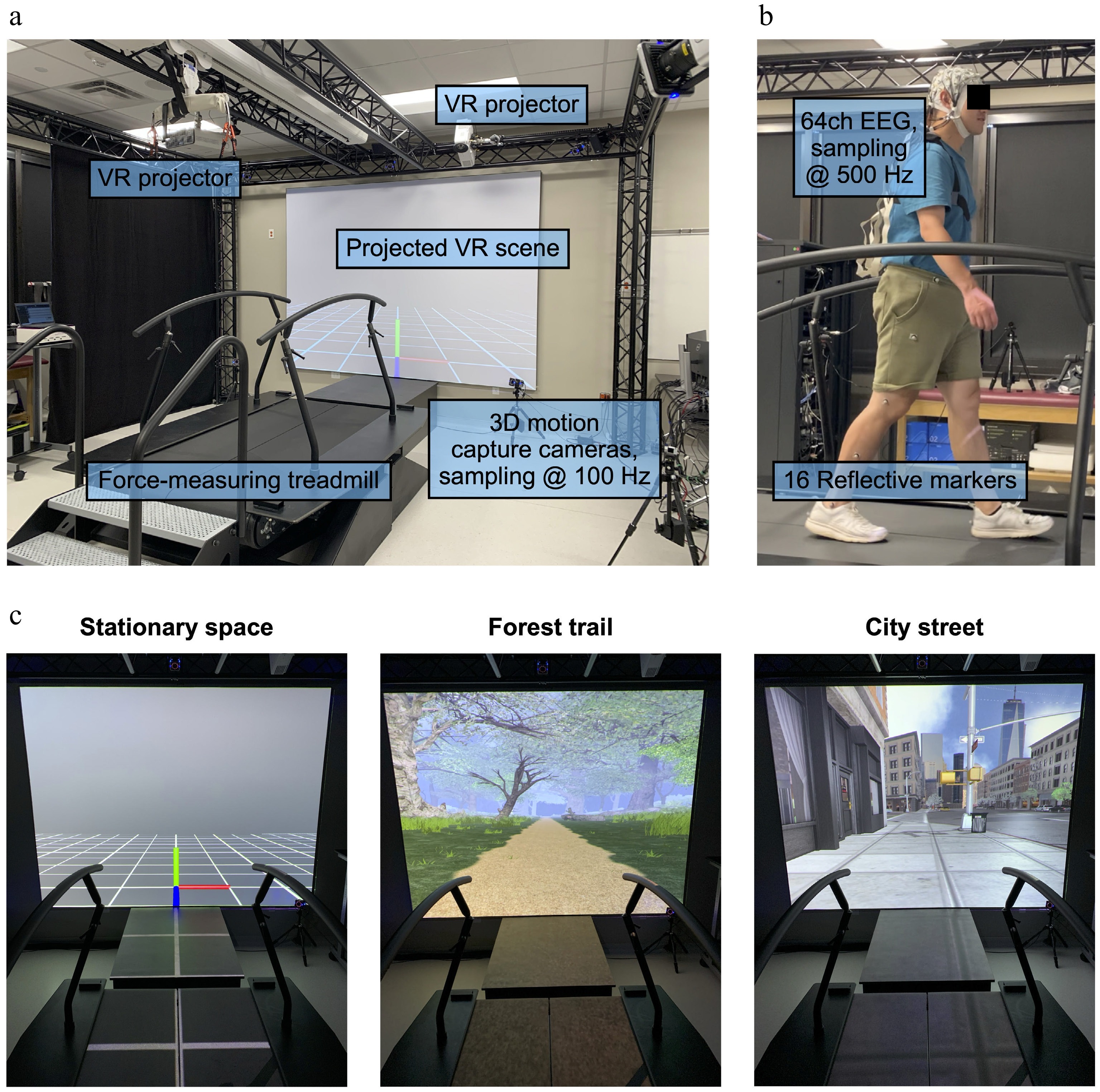

We used a 10-camera system (VICON, Oxford Metrics, Oxford, UK) to record lower-limb kinematics (Fig. 1a), and ground reaction forces were recorded from a split-belt force-measuring treadmill (M-Gait, Motek medical, Amsterdam, Netherlands). To record mobile high-density EEG signals, we used a 64-channel system (LiveAmp64, BrainProducts, Gilching, Germany) synchronized to the motion capture and force plate system (Fig. 1b). Virtual reality environments were generated by D-flow software (DIH, Amsterdam, Netherlands) and projected onto a screen at the front of the treadmill and the treadmill belts. Three visual environments were presented separately: (1) a stationary environment with an origin and grids, (2) a moving forest trail, and (3) a moving city street (Fig. 1c). Prior to walking conditions, we recorded the baseline electrical brain activity while participants stood motionless and viewed three visual environments (Fig. 1c) for 3 min. In each virtual environment, the participants walked continuously at four randomized gait speeds (0.6, 0.8, 1.0, and 1.5 m/s) for 3 min each.

Figure 1.

(a) Experimental setup. (b) Instrumented participant. (c) Virtual reality environments: (1) stationary empty space, (2) a moving forest trail, and (3) a moving city street that matched the treadmill belt's speed. VR, virtual reality.

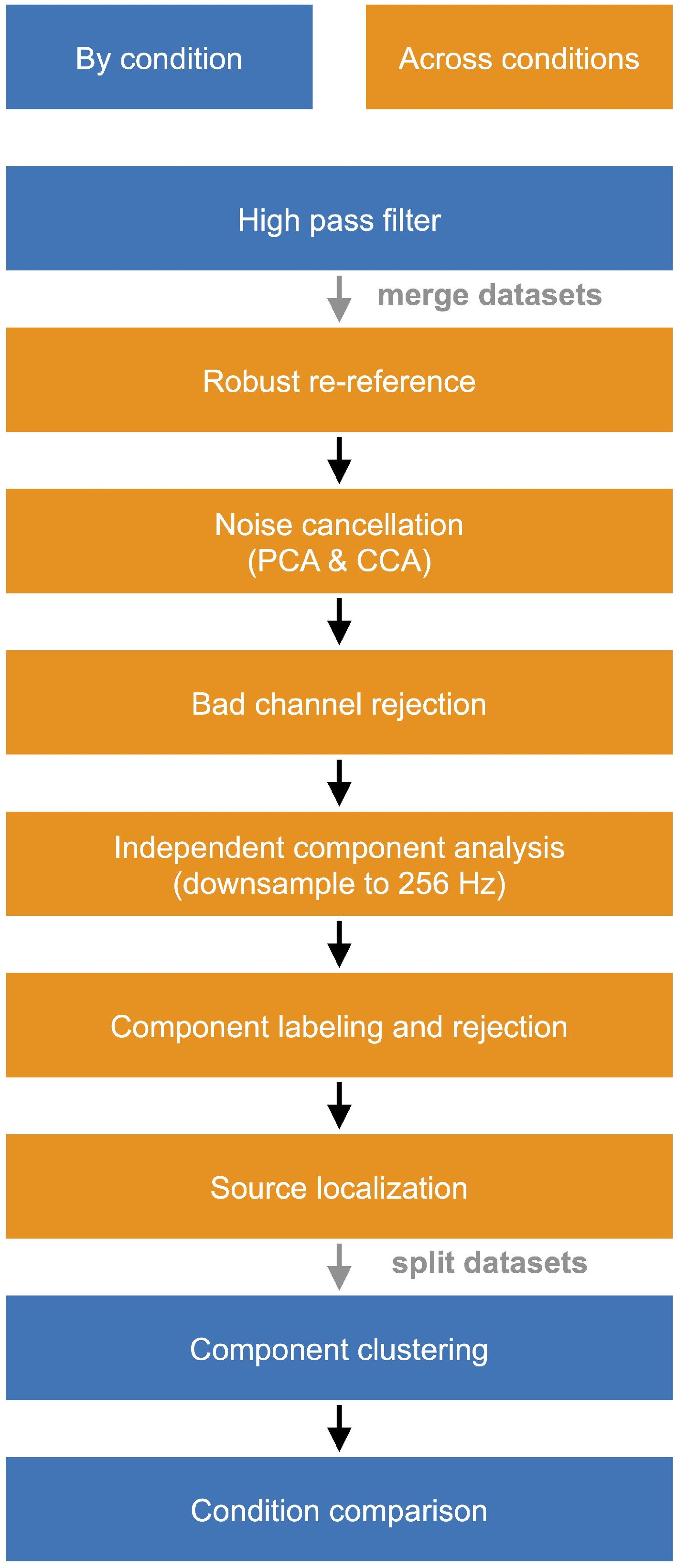

To remove noise from our recorded EEG signals, we applied an adapted data pre-processing pipeline[29,43], prior to extracting independent components, and performing electrocortical dipole fitting for each subject (Fig. 2), using EEGLAB[44]. We applied a 1-Hz high-pass filter and a robust reference[45] before applying sliding window spectral cleaning[46] using principal component analysis to remove transient large-amplitude fluctuations[29] and canonical correlation analysis to remove remaining electrical and muscle activity artifacts[29,34,43,47−50], separately for each experimental condition. We merged all pre-processed data, rejected remaining noisy channels, and downsampled the data to 256 Hz before applying an adaptive mixture independent component analysis (AMICA) in EEGLAB[51]. Independent components were labeled for their likelihood of brain, muscle, eye, or noisy signals[52], where components with a 90% or higher chance of being non-brain signals were rejected. Next, we modeled independent components as equivalent current dipoles using DIPFIT in EEGLAB, retaining components with a residual variance below 15%. We then segmented the continuous EEG data into the experimental conditions and calculated the power spectral density. The pink noise (1/f noise) was removed from the power spectral density[53]. On the basis of the independent component power spectrum, scalp map, dipole location, and dipole orientation, we applied K-means clustering (k = 15) to evaluate condition comparisons. Independent components were averaged within subjects for each cluster. The resultant cluster locations remained consistent across repeated clustering, indicating a reasonable quality, as evidenced by an average silhouette score of 0.48[43].

Figure 2.

EEG data processing pipeline. PCA, principal component analysis; CCA, canonical correlation analysis.

To analyze the effects of gait speed and the visual environment on EEG spectral power, we performed separate bootstrapped one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) at each frequency (EEGLAB) and identified spectral bins that showed significant differences among conditions within pre-defined spectral bands: delta (2−4 Hz), theta (4−8 Hz), alpha (8−13 Hz), beta (13−30 Hz), and gamma (30−50 Hz). After computing the spectral bins' means, we performed bootstrap ANOVAs among conditions with false discovery rate (FDR) corrections (adjusted p < 0.05). Statistically significant main effects were followed up by pairwise comparisons using bootstrapped t-tests with FDR corrections (adjusted p < 0.05).

-

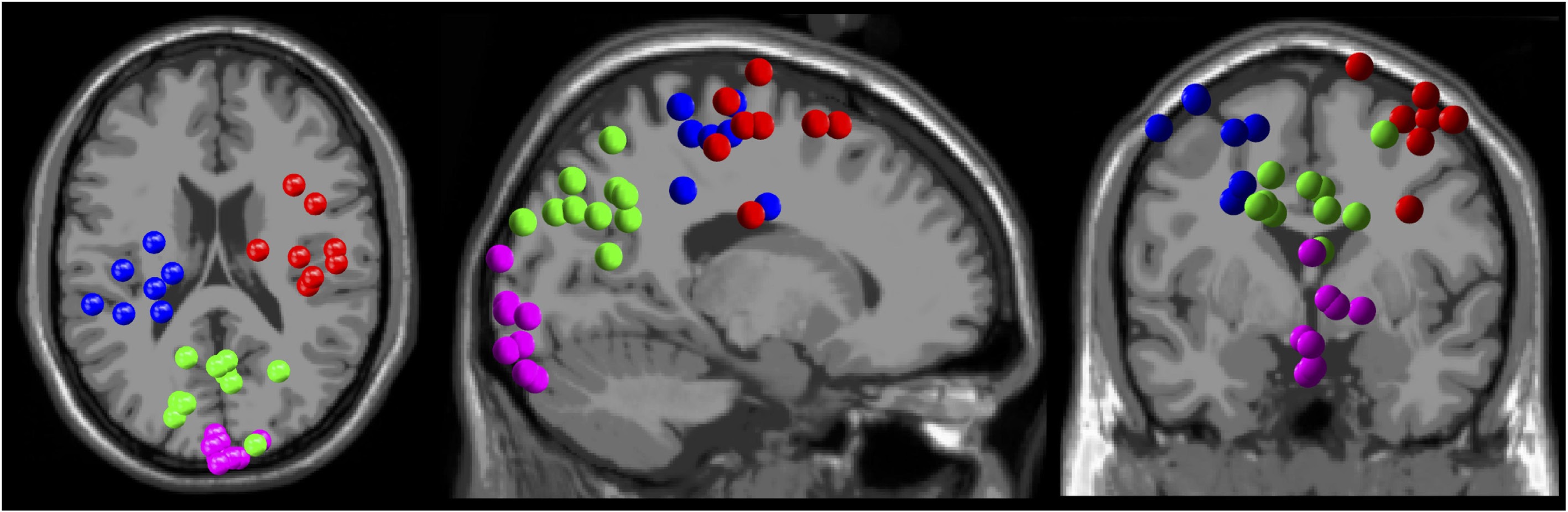

We obtained four cortical clusters that contained 7 to 9 of the 11 total participants from the left and right sensorimotor, parietal, and visual cortical regions (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Electrocortical dipole cluster locations. Left sensorimotor (blue), right sensorimotor (red), parietal (green), and visual (magenta) cortices.

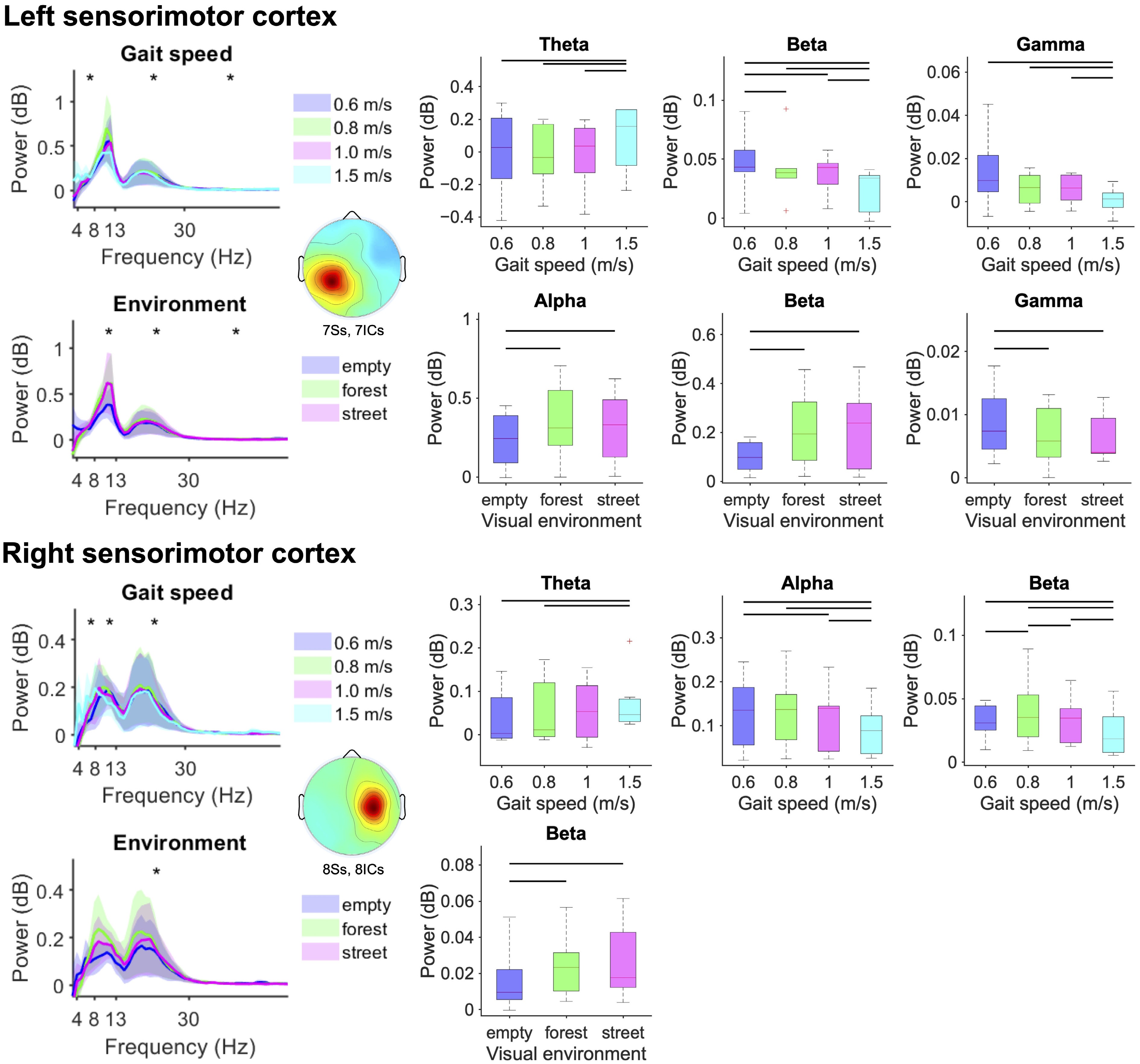

From the sensorimotor cortex, we identified reduced right sensorimotor alpha (F(3,5) = 6.89, p = 0.0072) and bilateral beta band spectral power (left: F(3,4) = 5.11, p = 0.0021; right: F(3,5) = 4.12, p = 0.0092), and greater bilateral theta power (left: F(3,4) = 5.48, p = 0.0038; right: F(3,5) = 2.51, p = 0.046) at faster gait speeds (Fig. 4, Rows 1 and 3; see the boxplots for condition-related pairwise comparisons). We also observed reduced gamma band power from the left sensorimotor cortex (F(3,4) = 7.11, p = 0.0021) at faster gait speeds (Fig. 4, Row 1). In the visual scenes, we identified reduced left sensorimotor alpha (F(2,5) = 7.31, p = 0.0087) and bilateral beta band sensorimotor electrocortical spectral power (left: F(2,5) = 6.53, p = 0.0087; right: F(2,6) = 3.55, p = 0.043) during walking in a stationary 3D grid environment compared with the moving forest trail and city street (Fig. 4, Rows 2 and 4). Gamma band spectral power from the left sensorimotor cortex (F(2,5) = 3.11, p = 0.029) was greater during walking in a stationary 3D grid environment compared with the moving forest trail and city street (3D grid vs. forest trail, p = 0.013; 3D grid vs. city street, p = 0.0096) (Fig. 4, Row 2).

Figure 4.

Mean left and right sensorimotor electrocortical spectral power (left) and boxplots aggregated within the theta (4−8 Hz), alpha (8−13 Hz), beta (13−30 Hz), and gamma (30−50 Hz) bands (standard error of the mean) (right) for each gait speed (top) and visual environment (bottom). Statistically significant differences among conditions are highlighted with black asterisk(s) for theta, alpha, beta, and gamma frequency bands (left) and black lines over the boxplots (right) (bootstrap ANOVA, p < 0.05, FDR corrected).

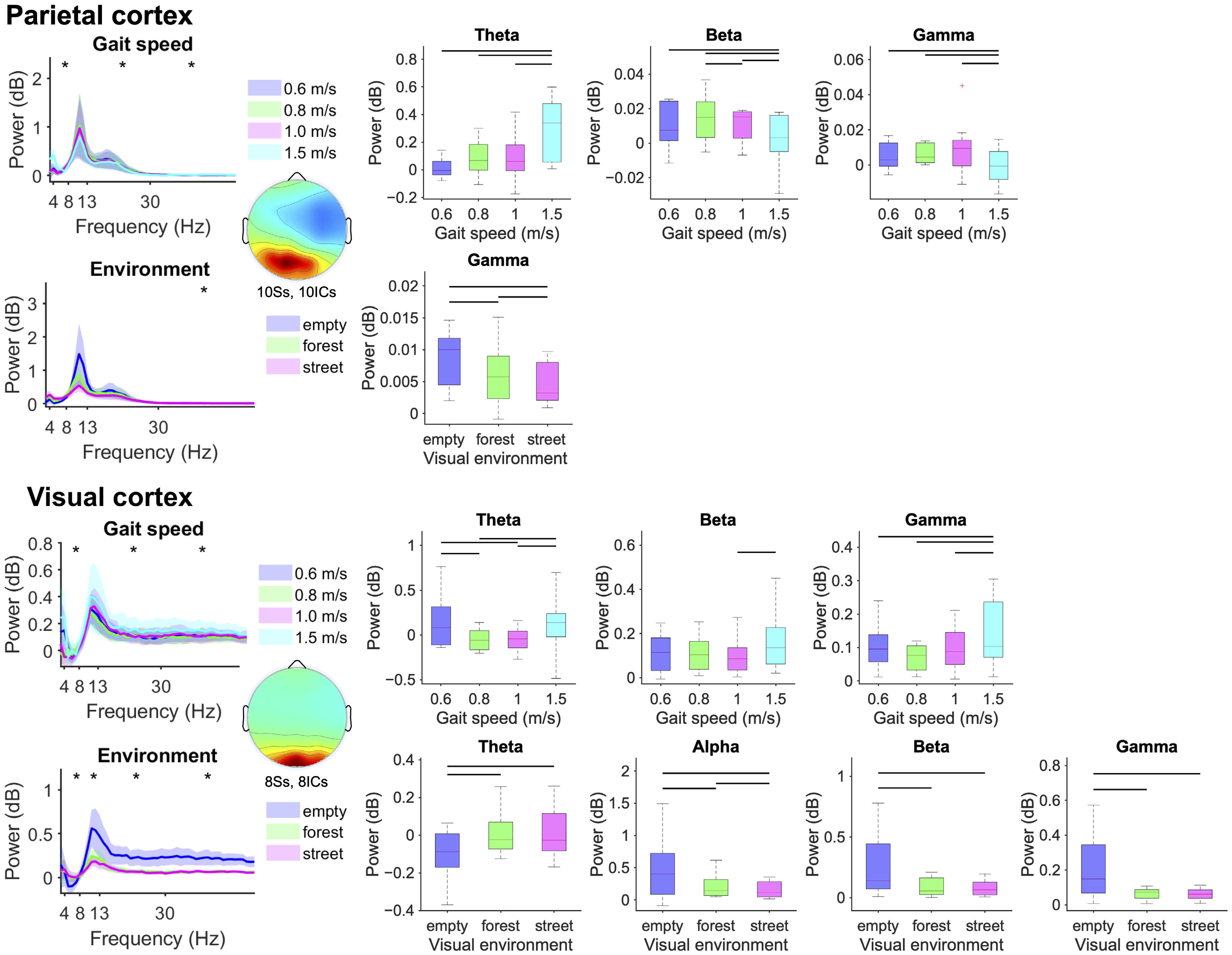

From the parietal cortex, we identified reduced beta and gamma band spectral power (F(3,7) = 4.08, p = 0.0026, gamma: F(3,7) = 5.26, p = 0.0026) and increased theta band power (F(3,7) = 10.91, p < 0.0001) at faster gait speeds (Fig. 5, Row 1). For the visual scenes, we observed progressively reduced gamma band parietal spectral power (F(2,8) = 5.26, p = 0.005) when navigating the stationary 3D grid environment compared with the moving forest trail and city street (Fig. 5, Row 2).

Figure 5.

Mean parietal and visual electrocortical spectral power (left) and boxplots aggregated within the theta (4−8 Hz), alpha (8−13 Hz), beta (13−30 Hz), and gamma (30−50 Hz) bands (standard error of the mean) (right) for each gait speed (top) and visual environment (bottom). Statistically significant differences among conditions are highlighted with black asterisk(s) for the theta, alpha, beta, and gamma frequency bands (left) and black lines over the boxplots (right) (bootstrap ANOVA, p < 0.05, FDR corrected).

From the visual cortex, we identified greater theta, beta and gamma band spectral power (theta: F(3,5) = 3.14, p = 0.0372; beta: F(3,5) = 3.00, p = 0.0372; gamma: F(3,5) = 3.27, p = 0.0372) at the fastest gait speed (Fig. 5, Row 3). We found increased theta band power (F(2,6) = 10.42, p < 0.0001) when navigating the forest trail and city street compared with the stationary 3D grid environment (Fig. 5, Row 4), and progressively reduced alpha, beta, and gamma band spectral power (alpha: F(2,6) = 3.89, p = 0.019; beta: F(2,6) = 4.03, p = 0.0043; gamma: F(2,6) = 5.11, p = 0.0008) when navigating the stationary 3D grid compared with the forest trail and city street (Fig. 5, Row 4).

-

Our aim was to determine the influence of visual environmental complexity and gait speed on human electrocortical spectral power during locomotion. In partial agreement with our hypotheses, at faster gait speeds, we identified greater theta band spectral power and reduced alpha, beta, and gamma band power from the left and right sensorimotor and parietal cortical regions, indicative of greater cortical processing. Cortical processing increased progressively when walking in stationary 3D space, compared with walking along a moving forest trail and city street. We identified greater theta band spectral power and reduced alpha, beta, and gamma band power from the visual cortex, along with reduced gamma band power from the parietal cortex, while navigating more complex visual environments. In contrast, sensorimotor alpha, beta, and gamma band spectral power reduced during walking in a stationary 3D space compared with moving virtual environments. Our findings highlight contrasting electrocortical responses among brain regions based on sensory integration during locomotion in virtual reality.

At faster gait speeds, the alpha, beta, and gamma bands' electrocortical spectral power decreased from the sensorimotor and parietal structures, but not the visual cortex. Mobile EEG measurements provide insight into synchronous neural activities within specific frequency ranges associated with regional and/or cross-regional brain processing[29,33,35,38]. Suppressed alpha and beta band oscillations during walking, compared with standing, reveal a state change in cortical excitability caused by movement[54]. Reduced electrocortical spectral power in the alpha and beta bands can be attributed to greater movement-related sensorimotor processing, and greater visuospatial and proprioceptive processing by the parietal cortex[29,33,54,55]. The parietal cortex serves an integrative function between the sensorimotor and visual cortical structures[56,57]; according to our results, it is mediated by changes in the alpha and beta bands' spectral power in response to the visual environment and gait speed. We also observed greater theta band power among cortical regions at faster gait speeds. Low-frequency oscillations in both the neocortex and hippocampus have been attributed to movement-related synchronization[58] and are important to sensorimotor integration, spatial navigation, and spatial learning[59]. Recordings from implanted electrodes and noninvasive EEG in epileptic human patients have revealed that hippocampal and neocortical theta activities are highly correlated during virtual driving[60], and greater hippocampal delta (<4 Hz) and theta band spectral power has been observed at faster moving speeds during virtual navigation[61], possibly related to spatial updating when viewing nongoal targets.

The effects of the visual environment on electrocortical spectral power had differential outcomes on the sensorimotor, parietal, and visual cortical regions. We identified greater theta band spectral power and reduced alpha, beta and gamma band power from the visual cortex during walking in more complex visual environments compared with less complex environments, indicative of greater visual cortical processing. The parietal electrocortical gamma band's spectral power decreased, likely due to the parietal cortex receiving transformed visual information from the visual system[25]. This finding may underscore cross-regional oscillations between the occipitoparietal and hippocampal regions during navigation, transforming external visuospatial information into internal cognitive mapping[62]. Our observed increases in the theta band's power and decreases in the alpha and beta bands' electrocortical spectral power are consistent with previous findings, highlighting a need to update spatial relationships between the body and the external environment during spatial navigation[60,61]. In contrast to the parietal and visual cortices, we identified reduced sensorimotor alpha and beta band spectral power during walking in less complex visual environments compared with more complex environments, indicative of greater sensorimotor cortical processing. These findings align with the previously reported effects of visual restriction on electrocortical spectral power during locomotion, increasing sensorimotor cortical processing in the absence of visual feedback[33]. Reduced sensorimotor alpha and beta band electrocortical spectral power while navigating less complex visual environments may reflect greater reliance on proprioceptive feedback[63] compared with visuospatial processing[64,65].

There are limitations in our study. Although we excluded functional deficits that could impair the ability to walk independently, we did not explicitly inquire about the participants' concussion history in the past 2 years, which could influence visual processing and balance during locomotion. We included only three levels of visual complexity to limit the duration of each participant’s visit, including the preparation of 64 wet EEG electrodes and motion capture markers. Further investigating a broader range of visual environmental complexity could help us to better understand how the human brain prioritizes contrasting sensory feedback in contrasting environmental conditions. Although mobile EEG recordings are susceptible to noise contamination, we have demonstrated the feasibility of isolating human electrocortical signals during gait using rigorous validations[46,49,50] and applications for studying human locomotor electrical brain dynamics[20,29,34,43,66]. It is possible that EEG signals' spectral power from the visual cortex could be contaminated by motion-induced artifacts and electrical neck muscle activity that could obscure electrocortical oscillations or lead to misinterpretations of the effects of visual environmental complexity on sensorimotor integration during walking. To address the influence of visual environmental complexity on information processing during visually guided gait, we previously evaluated the independent effects of gait speed and visual flow speed on electrocortical spectral power during walking on a treadmill in projected virtual reality in comparison with conditions with mismatched visual flow and gait speeds[43]. At faster gait speeds, beta band spectral power from the premotor, sensorimotor, and visual cortices decreased; at faster visual flow speeds, alpha and beta band spectral power from the sensorimotor and visual cortices decreased. Without the possible influence of gait-related noise contamination during conditions where the participants stood motionless and advanced through a virtual scene at a range of visual flow speeds, robust changes in electrocortical spectral power were observed[43]. Notably, our previous results showed that only during sensory conflicts, when visual flow and gait speed were mismatched, parietal electrocortical alpha band power increased, while power within the alpha and beta bands decreased at faster gait speeds[43]. Lastly, some of our electrocortical source clusters included seven to eight subjects each, fewer than our a priori target of 10 subjects to achieve 0.8 statistical power, which could limit the generalizability of our findings.

Our present results provide insight into how cerebral cortical networks process sensory information at the system level during visually guided locomotion. Similar to the sensory reweighting hypothesis for sensory integration during postural and balance control[67−69], where contributions of proprioceptive, vestibular, and visual systems change dynamically in response to environmental or experimental conditions to prevent instability, our findings during human gait showed greater visuospatial processing accompanied by reduced sensorimotor processing as the visual environmental complexity increased, an effect that was distinct from visual flow, whether due to self-motion or not[43]. Both the aging process and motor deficits like Parkinson’s disease can influence the process of sensory reweighting[70−72], where reduced weighting of certain sensory feedback or failure of reweighting occurs. Future research may provide clinical insights into postural stability during locomotion in aged populations and patients with Parkinson’s disease. Using virtual reality, visual environmental complexity can be tuned during the early phase of rehabilitation to reinforce the use of sensorimotor feedback, gradually increasing visual environmental complexity back to real-life levels in later phases. Evaluating electrocortical spectral power from sensorimotor and visual cortices, especially the alpha/beta power increase from the sensorimotor cortex, could serve as a predictor of fall risk[73].

We found that electrocortical spectral power among different brain areas was differentially modulated by gait speed and visual environmental complexity during treadmill locomotion in projected virtual reality. We identified greater sensorimotor and parietal cortical processing at faster gait speeds, and greater occipitoparietal but lesser sensorimotor cortical processing in more complex visual environments. Because the parietal cortex showed spectral power responses similar to the sensorimotor cortex in response to altered gait speed, and spectral power responses similar to the visual cortex in response to the visual environment, our results highlight the integrative role of the parietal cortex in visuospatial processing during human gait. Future studies aimed at investigating interregional connectivity and interactions between the body and virtual or real-world objects in the environment during visually guided locomotion can help to uncover neurophysiological biomarkers for tracking cortical engagement while using immersive technologies and for developing gait-related brain–computer interfaces. Future studies should consider visuomotor interactions during overground, self-paced, and outdoor walking conditions. This knowledge is critical for better understanding healthy human locomotor control and cortical pathways that may be disrupted in populations that are at elevated fall risk during locomotion.

-

All experimental protocols adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the institutional review board at Texas A&M University (approval number: IRB2021-1198D).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study design: Cheng YP, Nordin AD; data collection and analysis: Cheng YP; manuscript writing and reviewing: Cheng YP, Nordin AD. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

We thank the Sydney and J.L. Huffines Institute for Sports Medicine and Human Performance for their Graduate Research Grant supporting the data collection. We also thank Alexandra Long and Lorenzo Lopez for their assistance with data collection.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng YP, Nordin AD. 2025. Navigating complex virtual environments at a range of gait speeds differentially modulates human sensorimotor and occipitoparietal electrocortical spectral power. Visual Neuroscience 42: e018 doi: 10.48130/vns-0025-0017

Navigating complex virtual environments at a range of gait speeds differentially modulates human sensorimotor and occipitoparietal electrocortical spectral power

- Received: 18 March 2025

- Revised: 17 July 2025

- Accepted: 17 July 2025

- Published online: 16 September 2025

Abstract: Visually navigating environmental terrain on foot requires the human cerebral cortex to process multisensory information. To study the effects of gait speed and visual environment on human electrocortical spectral power dynamics during visually guided treadmill locomotion, we recorded high-density mobile electroencephalography (EEG) signals from 11 healthy subjects at a range of treadmill walking speeds (0.6, 0.8, 1.0, and 1.5 m/s) in three contrasting virtual reality scenes: (1) a stationary three-dimensional (3D) grid, (2) a moving forest trail, and (3) a moving city street that matched the treadmill's gait speed. Sensorimotor and parietal cortical regions showed greater theta band spectral power (4−8 Hz) and reduced the alpha (8−13 Hz), beta (13−30 Hz), and gamma band (> 30 Hz) power at faster walking speeds, indicative of greater cortical processing. In contrast, visual and parietal cortical processing increased while walking along a virtual forest trail and city street compared with a stationary 3D grid, but sensorimotor cortical processing increased in the absence of a moving visual environment. Differential responses among cortical structures while navigating contrasting environments at different speeds provide insight into sensory reweighting that can improve our understanding of cortical processing during gait and help identify biomarkers for predicting locomotor deficits and the risk of falls due to competing sensory demands.

-

Key words:

- Electroencephalography /

- Vision /

- Gait /

- Virtual reality /

- Spectral power