-

In the food processing industry, there is a growing interest in incorporating nutraceuticals and natural antioxidants into food products. Scientific communities have been exploring these functional ingredients from native foods for their unique flavors and properties. Decalepis hamiltonii, popularly known as swallow root, is known for its rich natural flavor and bioactive properties. D. hamiltonii extract is listed as a flavoring agent in FDA regulations as a 'generally recognized as safe' (GRAS) substance. The aqueous extract from tubers of D. hamiltonii is reported to be rich in bioactive compounds and possesses high antioxidant potential[1,2]. The tuberous roots extract is rich in polyphenols and flavonoids; among the molecules, 2-hydroxy-4-methoxybenzaldehyde (2H4MB), an isomer of vanillin, is reported as a major (80%–90%) molecule[3]. The present-day challenge is in the processing of this tuber, and very few reports are available on the application and processing of these bioactives[4]. Currently, efforts are being made to enhance the value of these high-value bioactives for various food processing industries, and microencapsulation is one such emerging technology that offers several advantages and numerous applications. Natural swallow root extract is sensitive to temperature, and encapsulating these metabolites offers easy application, reduces volatility, controls release, minimizes reactivity with other product ingredients, and provides stability in food products.

Encapsulation is a widely used technique used to pack sensitive molecules within a core material to protect them from external influence[5,6]. In food processing, freeze-drying and spray-drying are reported to be extensively used techniques for processing food ingredients[6].

The selection of a suitable carrier material is a critical step during the encapsulation process, which depends on the nature and components of the application. Natural polymers like carbohydrates (dextrin, cellulose), proteins (whey protein), gums (gum acacia, guar), emulsifiers (sodium caseinate), fibers lipids, fats, and waxes are reported to be widely used as encapsulating agents for food applications[7,8]. The physicochemical characteristics of these carrier materials, i.e., their film-forming ability, nonreactivity, molecular weight, solubility, glass transition temperature, emulsifying properties, viscosity, and drying properties, play a major role in the processing efficiency and stability of microcapsules[9]. The choice of carrier material will determine the feed properties before drying, retention of the bioactives during processing, and the stability of the encapsulated powder after drying[10]. However, a single carrier material may not possess all the desired properties ideal for retaining bioactive compounds with a long shelf life at a minimal cost. To achieve these different types of combinations, two or more carrier materials can be blended to investigate the synergistic effect. The microcapsules formed are stable because of the polymer-bioactive and polymer-polymer interactions (modification) and synergistic influences (blends of polymers)[8,11]. Studies on microencapsulation of different flavors, bioactives, and natural antioxidant molecules from other sources are widely reported[11−14]. Similarly, encapsulation of vanillin with spray freeze-drying[15] and spray-drying[16−21] has been reported.

Decalepis hamiltonii's main bioactive, i.e., 2-hydroxy-4-methoxybenzaldehyde or 2H4MB, has not been explored in food processing/ product formulations. Encapsulation of these bioactives using commercial techniques such as spray-drying or freeze-drying may offer adequate stability and delivery in food products. In the present work, the role of carrier materials in encapsulating flavor-rich extracts from tubers of D. hamiltonii was investigated using spray-drying and freeze-drying techniques. Maltodextrin (carbohydrate), gum acacia (gum), and sodium caseinate (protein) were used alone and also as blends to understand their collective effect during encapsulation. The spray-dried powders were analyzed for quality with respect to their powder characteristics, biochemical properties, and storage stability.

-

As carrier materials, gum acacia (AC) powder LR was sourced from SD Fine Chem Ltd (Mumbai, India), maltodextrin (MDX) was from Loba Chemie PVT. Ltd. (Mumbai India), and sodium caseinate (SC) was from Sisco Research Laboratories Pvt. Ltd. (SRL), India. The 2-hydroxy-4-methoxy benzaldehyde was procured from Fluka Chem, Switzerland. All other chemicals used were of analytical grade.

Decalepis hamiltonii extract preparation

-

D. hamiltonii Wight & Arn. tubers were harvested from a 10-year-old garden-grown plant at CSIR-CFTRI. Tubers measuring 25–40 cm long and 4–5 cm in diameter were selected and washed thoroughly with water to remove soil remnants, followed by washing with Tween 20 detergent. Once again, the tubers were thoroughly cleaned with distilled water twice and then subjected to drying at 40 °C for 16–20 h to remove water content and maintain a uniform moisture content (≤ 10%). The dried tubers were finely ground into a powder using a multi-mill, resulting in uniform particle sizes of around 3–4 mm. The tuber powder was then subjected to steam distillation for the extraction of bioactives[22,23]. The aqueous extract with bioactives obtained was used for microencapsulation.

Feed preparation

-

The feed solution was prepared by mixing the aqueous extract of D. hamiltonii tuber with the carrier material. The aqueous extract (1 L) was mixed with a carrier material (10% w/v) using a tabletop magnetic stirrer. The carrier materials were used one at a time ie., gum acacia (AC), maltodextrin (MDX), and sodium caseinate (SC), and in a 1:1 ratio combination maltodextrin with gum acacia (MA), maltodextrin with sodium caseinate (MS), and gum acacia with sodium caseinate (AS) during the study. The uniform feed solution was fed into the spray dryer for microencapsulation.

Spray-drying

-

The feed containing D. hamiltonii extract with the carrier materials was pumped into a pilot-scale spray drier (Bowen, UK 1216 BE; double-fluid nozzle atomizer height: 0.72 m, diameter: 0.76 m, cone height: 0.74 m, evaporation capacity: 5 kg·h−1). The drying conditions were optimized according to preliminary studies of 2H4MB and total phenolic content. The inlet air temperature was 110 ± 2 °C, the outlet air temperature was 60 ± 2 °C, air pressure was 24 psi, and the feed flow rate was 20 ± 1 mL·min−1[15]. To maintain a uniform concentration of feed and prevent settling, the feed was continuously stirred as it was fed into the dryer. The microencapsulated powders were used for further analysis.

Freeze-drying

-

The feed, which was composed of D. hamiltonii extract and the carrier materials, was subjected to freeze-drying using a Lyodryer LT58 (ISI Lyophilization Systems Inc., USA). For this, 30 mL of the feed solution was poured into a glass plate (120 mm in diameter, 25 mm in height) and subjected to freezing at −20 °C. The ice-covered samples were dried for 16 h at −51 °C under a pressure of less than 0.12 mbar. The resulting freeze-dried samples were used for further analysis[24,25].

Powder yield

-

The powder yield obtained after microencapsulation was determined by using the following Eq. (1). The percentage yield was calculated on a weight basis (%, w/w).

$ \rm Yield\; ({\text{%}}w/w)=\dfrac{w_p}{T_S} \times 100 $ (1) where, Wp is the weight of the encapsulated powder collected after spray-drying and TS is the total soluble solid content in the feed.

Encapsulation efficiency

-

The surface bioactives, i.e., 2H4MB, total phenolic content, and total flavonoid content, were calculated according to the method reported by Swetank et al. with minor modifications. For this, 5 g of the microencapsulated sample was added to 50 mL of methanol and gently shaken for 10–15 s to extract the surface bioactives. The solvent mixture was passed through filter paper to separate the sample powder, and the solvent was collected separately. The solvent mixture was evaporated, and the encapsulation efficiency was checked by the following equation:

$ \begin{split}&\rm Encapsulation\;efficency\;({\text{%}}) =\\&\quad\rm \dfrac{Total \;bioactives - Surface \;bioactives}{Total\;bioactives} \times 100\end{split}$ (2) where, 'Total bioactives' refers to the molecules (i.e., polyphenols, flavonoids, and 2H4MB) present on the encapsulated powder and 'Surface bioactives' are the molecules present on the outer surface of the encapsulated powder.

Moisture content

-

The percentage of moisture present in the microencapsulated powder was determined by using an infrared (IR) moisture meter (HMB100, Wenser, Chennai, India). For this, 2 g of powder was measured in a sample holder and kept in a moisture analyzer at a fixed temperature (80 °C) until a constant weight was recorded. The moisture in the powders was evaluated in terms of percentage dry weight, and the average mean of triplicate data is reported[24].

Microscopy

-

The surface morphology of the microencapsulated samples was observed using a scanning electron microscope (Leo 435 VP, Leo Electronics Systems, Cambridge, UK). The spray-dried microcapsules were adsorbed on the surface of copper grids and subjected to gold coating. The images of the microstructures of the coated samples at 5,000× magnification are reported. Similarly, freeze-dried samples were coated, and images of their microstructure were recorded at 2,000× magnification[15,24].

Particle size analysis

-

The spray-dried powder was observed using a Microtrac Turbo Trac dispersion system (BlueWave, Pennsylvania, USA) with a Particle Size Analyzer (S3500 Series, BlueWave, Pennsylvania, USA). Particle sizes ranging across 0.25–3,000 μm can be measured using this apparatus. The powder samples obtained after encapsulation were analyzed for particle size. The samples were analyzed in triplicate, and the mean values are reported[15,24].

Flow properties

-

The powder characteristics of the spray-dried samples were determined using a tap density tester (Electrolab, ETD-1020). The samples' Carr's index (CI), which determines flow properties, and Hausner ratio (HR) were used to determine the interparticle friction of the spray-dried powder. For this, 10 g of the sample was loaded in the measuring cylinder, and the change in the volume of dried powder before and after tapping was recorded. The following equations were used to determine the CI and HR from the recorded data.

$ \rm{C}I=\dfrac{V_B-V_T}{V_T} $ (3) where, VB is the bulk volume and VT is the tapped volume of the spray-dried powder.

$ \mathrm{H}\mathrm{R}=\dfrac{100}{100-\mathrm{C}\mathrm{I}} $ (4) Color

-

The color of the encapsulated powder samples was measured using L, a*, and b* values on a Konica Minolta CM-5 instrument (VA, USA). The light absorbance was initially standardized by calibrating the absorbance with a standard white disk. Then the samples were analyzed by placing them in a plastic sample cup, which was 4 cm × 1 cm in diameter and height, and the L, a*, and b* values were measured. The measurements were recorded in triplicate, and mean values are reported[16].

Core and wall interaction

-

The interaction between the carrier material and bioactives was observed using Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. The spray-dried sample and individual carrier materials' spectra were measured (Tensor II, M/s. Bruker, Germany) at a scanning range of 4,000–400 cm−1. The transmission fingerprint was recorded and analyzed with reference spectra to deduce the bioactives' interaction within a functional group of the carrier[15].

2H4MB quantification

-

Quantification of 2H4MB in the microencapsulated samples was performed using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (SPD-20AD, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) and confirmed by 1H nuclea magnetic resonance (NMR) (Bruker Avance Spectrometer, Rheinstetten Germany) equipped with double-resonance broadband observation probe at 500 MHz. The samples were separated using a C18 (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm in diameter) column (YMC column Waters Corporation, USA) using an isocratic solvent system comprising methanol, acetonitrile, water, and acetic acid (47:10:42:1)[23,26]. The samples were quantified on the basis of their retention times using the corresponding standards (Sigma USA) using an ultraviolet (UV) detector. The sample, with a 20-µL volume, was injected into the column at a temperature of 24 ± 20 °C, and 2H4MB was observed to be eluted at 8.5 min. The spray-dried sample and standard were diluted with methanol-d4 and confirmed through NMR. The peaks were calibrated using the internal standard sodium trimethylsilyl propane sulfonate (DSS), and the following experimental parameters were employed during sample analysis: number of scans = 128, relaxation delay = 3 s, acquisition time (AQ) = 1.99, spectral width = 20.6 parts per million (ppm), and offset = 15.3 ppm. The acquisition of sample spectra (version 2.1) and the processing of 1H-NMR spectra (version 4.07) were performed using Topspin software.

Estimation of total phenolic content (TPC)

-

The methanol extracts of microencapsulated samples were analyzed for total phenolics using a spectrometry-based Folin-Ciocalteu's reagent assay[27]. The 80% methanol extract from the microencapsulated sample was mixed with 3 mL of distilled water and 0.5 mL of Folin-Ciocalteau's reagent, followed by 2 mL of 20% Na2CO3. The tubes were vortexed and placed in a boiling water bath for precisely 1 min. 0.1 to 1 mL of working standard (gallic acid, 0.1 mg·mL−1) was used to prepare the standard curve. After incubation, samples were measured for phenolic content at 650 nm and expressed in terms of Gallic Acid Equivalent (mg·GAE g−1 extract).

Estimation of total flavonoid content

-

The total flavonoid content of the sample was estimated using the spectrophotometric method[27]. The flavonoid content in an 80% methanol extract of the microencapsulated sample was determined and expressed in terms of quercetin equivalent (QE) mg·g−1 extract. The extract was diluted with 5 mL of distilled water. For the quantification of total flavonoids, 0.1 mL of the extract was pipetted out into a test tube; 0.1–1 mL of quercetin (0.1 mg·mL−1) was used as the working standard for preparing the standard curve. The volume in all the tubes was made up to 4 mL with distilled water. To this, 0.3 mL of 5% sodium nitrate was added in each test tube, and the samples were incubated for 5 minutes at room temperature. Next, 0.3 mL of a 10% AlCl3 solution was added to each tube and incubated for 5 minutes. Then 2 mL of 1 M NaOH was added to the tubes, and the absorbance was measured at 510 nm and indicated in terms of quercetin equivalent.

Antioxidant activity

2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl assay

-

The methanol extracts of the microencapsulated sample were examined for free radical scavenging potential using the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay[28]. Different concentrations of the extract were mixed with 0.1 mol·L−1 DPPH reagent. After incubation, absorbance was measured at 517 nm.

Phospomolybdate assay

-

The total antioxidant activity of the methanol extract from microencapsulated samples was measured by mixing it with a sodium phosphate and ammonium molybdate solution, followed by incubation at 95 °C for 90 min. The absorbance of the mixture was measured at 695 nm and expressed as mg·100 g−1 dry powder[29].

Ferric reducing antioxidant power assay

-

The reducing power potential of the methanol extract was assessed using a ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay[30]. To different concentrations of the sample, methanol extract, a phosphate buffer, and potassium ferricyanide (1:1) were added. To the solution, trichloroacetic acid was added, and it was centrifuged to separate the supernatant. Then ferric chloride was added to the diluted supernatant (1:1), and the absorbance of the solution mixture was measured at 700 nm.

Microbial analysis

-

The samples were analyzed for microbial stability using total plate counts, yeast and mould counts, and coliform tests. The sample (1 g) was dissolved in 0.9% saline (10 mL) and serially diluted for seven dilutions, then 100 μL of each dilution was spread aseptically onto plates containing nutrient agar, potato dextrose agar, and Escherichia coli agar (Hi-Crome, India). The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h for the bacterial count and at 28 °C for 48 h for the yeast count; the colony count was expressed in log colony-formun units (cfu) g−1[29].

Storage studies

-

The samples were stored in polyethylene terephthalate (PET) laminate pouches at room temperature (27 ± 2 °C). The bioactives and microbial stability of the stored samples were monitored at regular time intervals of 1 month for 3 months.

Statistical analysis

-

The data were recorded in triplicate and statistically validated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey's post hoc test (p < 0.05) using SPSS software (version 17). FTIR fingerprint data were analyzed using Origin Pro software (2018).

-

In the present study, three different carrier materials, namely maltodextrin (MDX), gum acacia (AC), and sodium caseinate (SC), which are widely used in food applications, were employed for the encapsulation of Decalepis hamiltonii extract. The physicochemical properties of the extract used during spray-drying are shown in Table 1. The feed, which was prepared using the carrier materials one at a time and in combination, was used in the preparation of spray-dried powder. Table 2 presents the variation in bioactives, including 2H4MB, phenolics, flavonoids, and powder yield, of spray-dried samples with the different carrier materials. Among the carrier materials used in the study, SC exhibited the highest bioactive retention of 2H4MB (60.2 ± 1 µg·g−1), polyphenols (63.3 ± 2.7 mg·100 g−1), and flavonoids (23.8 ± 0.2 mg·100 g−1) observed after spray-drying. This can be attributed to the protein-based carrier materials' film-forming abilities during the encapsulation process. In spray-drying, the highest degradation of the bioactive is reported to occur in the initial stages of drying, before dry crust formation on the surface of the microcapsule[8,9]. SC, a protein found in nature, is reported to play a role in decreasing the glass transition temperature and accelerating microcapsule wall formation around the core material, shielding the bioactives[7,31]. During drying, the protein is reported to exhibit superior migration towards the outer edge of the droplet, forming a protein-concentrated layer on the microcapsule's surface[5]. After film formation, the drop in the surface glass transition temperature increases through exposure to the hot air of the dryer, which shields the core particle and results in an increase in the retention of bioactives[32].

Table 1. Physicochemical properties of D. hamiltonii aqueous extract used for spray-drying and freeze-drying.

Sample

No.Physicochemical

propertyAqueous extract of

D. hamiltonii tuber1 pH 4.8 ± 0.5 2 Total solid content (Brix) 3.2 ± 0.2 3 2H4MB 5.3 ± 0.1 mg·100 mL−1 4 Phenolics 27.4 ± 0.5 mg·100 mL−1 5 Flavonoids 13.7 ± 0.2 mg·100 mL−1 Values are the mean ± SE of three replicate analyses. Table 2. Physical, biochemical, and microbial characteristics of microencapsulated samples.

Spray-drying Carrier material MDX AC SC MA MS AS Carrier material ratio 1:0 1:0 1:0 1:1 1:1 1:1 Yield % (w/w) 60 ± 2d 43 ± 4bc 40 ± 2bc 45 ± 2bc 54 ± 4d 33 ± 2a Moisture % (w/w) 3.3 ± 0.2b 3.5 ± 0.1b 4.2 ± 0.1b 3.7 ± 0.1b 4.3 ± 0.2b 3.4 ± 0.3a Color L* 73.3 ± 0.08c 72.6 ± 0.01c 64.3 ± 0.01a 73.6 ± 0.05cd 74.8 ± 0.2d 67.6 ± 1.1b a* 7.81 ± 0.07c 8.7 ± 0.02e 4.9 ± 0.1a 8.4 ± 0.01d 7.0 ± 0.1b 9.2 ± 0.1f b* 20.8 ± 0.2c 22.6 ± 0.2e 14.9 ± 0.3a 22.2 ± 0.1e 19.7 ± 0.3b 21.5 ± 0.2d 2H4MB content (µg·g−1) 53.9 ± 2b 54.9 ± 6d 60.2 ± 1e 53.6 ± 2c 58.6 ± 2d 50.0 ± 7a Total phenols content

(mg·100 g−1 of gallic acid equivalent)28.6 ± 1.1a 38.4 ± 0.5b 63.3 ± 2.7c 20.8 ± 1.3a 55.4 ± 2.3c 24.8 ± 1.3a Total flavonoid content

(mg·100 g−1 of quercetin equivalent)22.9 ± 0.4ab 23.8 ± 0.5abc 23.8 ± 0.2abc 22.4 ± 0.4a 24.7 ± 0.7bc 25.7 ± 0.7c DPPH (mg·IC50 mL−1) 86.7 ± 1f 49.6 ± 0.6c 37.7 ± 1a 81 ± 0.8e 39 ± 1ab 57.0 ± 1.9d FRAP 36 ± 0.6b 52.4 ± 1cd 88.6 ± 2f 29 ± 5a 81 ± 2e 50.0 ± 0.4c Phospomolybdate assay

(mg·100 g−1 ascorbic acid equivalent)51.6 ± 1b 79.6 ± 2d 131.3 ± 2f 43.2 ± 0.7a 123 ± 0.6e 64.3 ± 2c Total plate count Nil Nil Nil Nil Nil Nil Yeast and mould Nil Nil Nil Nil Nil Nil Coliform Nil Nil Nil Nil Nil Nil Freeze-drying Carrier material ratio 1:0 1:0 1:0 1:1 1:1 1:1 Yield % (w/w) 97 ± 0.5 92 ± 0.2 94 ± 0.4 93 ± 0.5 96 ± 0.2 94 ± 0.2 Moisture % (w/w) 6.8 ± 0.1ab 7.6 ± 0.2c 7.1 ± 0.2ab 6.7 ± 0.1a 6.8 ± 0.2ab 7.1 ± 0.1ab Color L* 56.2 ± 0.09c 55.5 ± 0.06c 53.0 ± 0.01a 53.8 ± 0.01b 53.9 ± 0.1b 57.6 ± 0.05d a* 11.2 ± 0.03c 10.4 ± 0.06b 8.0 ± 0.03a 11.6 ± 0.01c 11.0 ± 0.1c 10.4 ± 0.02b b* 19.6 ± 0.04d 18.7 ± 0.08bc 14.8 ± 0.02a 19.4 ± 0.01cd 18.2 ± 0.30b 19.7 ± 0.02d 2H4MB content (µg·g−1) 62.9 ± 2a 71.4 ± 4b 75.7 ± 5d 68.3 ± 2bc 70.7 ± 2c 73.6 ± 1c Total phenol content

(mg·100 g−1 of gallic acid equivalent)35.2 ± 1.3a 49.5 ± 3.2b 72.2 ± 1.8d 39.0 ± 1.1a 58.5 ± 2.1c 62.5 ± 0.7b Total flavonoid content

(mg·100 g−1 of quercetin equivalent)24.9 ± 0.4a 24.2 ± 0.4a 46.3 ± 0.7b 43.5 ± 1.1b 46.3 ± 0.7b 52.7 ± 1.1c DPPH (mg IC50 mL−1) 93.6 ± 1e 62.2 ± 1d 23.3 ± 0.7ab 106.6 ± 2f 44 ± 1.2c 21.3 ± 0.5a FRAP 51.3 ± 2a 52.8 ± 0.5a 117.5 ± 4c 50.6 ± 0.4a 81.5 ± 1b 143.3 ± 4d Phospomolybdate assay

(mg·100 g−1 ascorbic acid equivalente)63.5 ± 0.3ab 84.5 ± 2c 132.6 ± 1e 59.9 ± 2a 117 ± 0.8d 163.6 ± 1f Total plate count Nil Nil Nil Nil Nil Nil Yeast and mould Nil Nil Nil Nil Nil Nil Coliform Nil Nil Nil Nil Nil Nil MDX, maltodextrin; AC, gum acacia; SC, sodium caseinate; MA, maltodextrin + gum acacia; MS, maltodextrin + sodium caseinate; AS, gum acacia + sodium caseinate; IC50, half-maximal inhibitory concentration. (Lowercase letters a, b, c, d, e, indicate statistical significance of data sets). The molecular conformation, diffusivity, and amphiphilic characteristics of the caseins in sodium caseinate enable uniform distribution around the microcapsule's surface, resulting in improved encapsulation[33]. The maltodextrin + sodium caseinate (MS) carrier material was found to be the second best in retention of bioactives: 2H4MB content, 58.6 ± 2 µg·g−1; phenolics, 55.4 ± 2.3 mg·100 g−1; flavonoids, 24.7 ± 0.7 mg·100 g−1. The MS blend was made by mixing a polysaccharide-based carrier material (maltodextrin) in combination with a protein-based carrier material (sodium caseinate), showing a higher emulsifying ability and ability to form stable microcapsules. The blending of carrier materials is reported to alter the emulsifying properties of the wall material and increase the retention of bioactives, which was evident in the present study[8]. In MS microcapsules, during drying, the polymer (MDX) provides structure through glass formation and the proteins (SC) contribute to emulsification and film formation ability[34]. The mixing of carrier materials, i.e., MDX with SC increases crust formation by changing the drying characteristics of the microcapsule wall. The percentage retention of 2H4MB compounds in terms of the extract content in different microcapsules in decreasing order was SC (14.7%), MS (14.3%), gum acacia + sodium caseinate (AS) (13.7%), AC (13.5%), maltodextrin + gum acacia (MA) (13.1%), and MDX (13%). However, the percentage of total phenolic content retained within the extract was in the following decreasing order: SC (30%), MS (27.9%), AS (26.6%), MA (25.5%), and AC (18.3%), and MDX (13%), respectively. Similarly, the flavonoid content was in the following order: AS (24.7%), MS (23.5%), SC (22%), AC (22%), MA (21.7%), and MDX (21%). This variation can be attributed to the change in the drying properties with the different carrier materials.

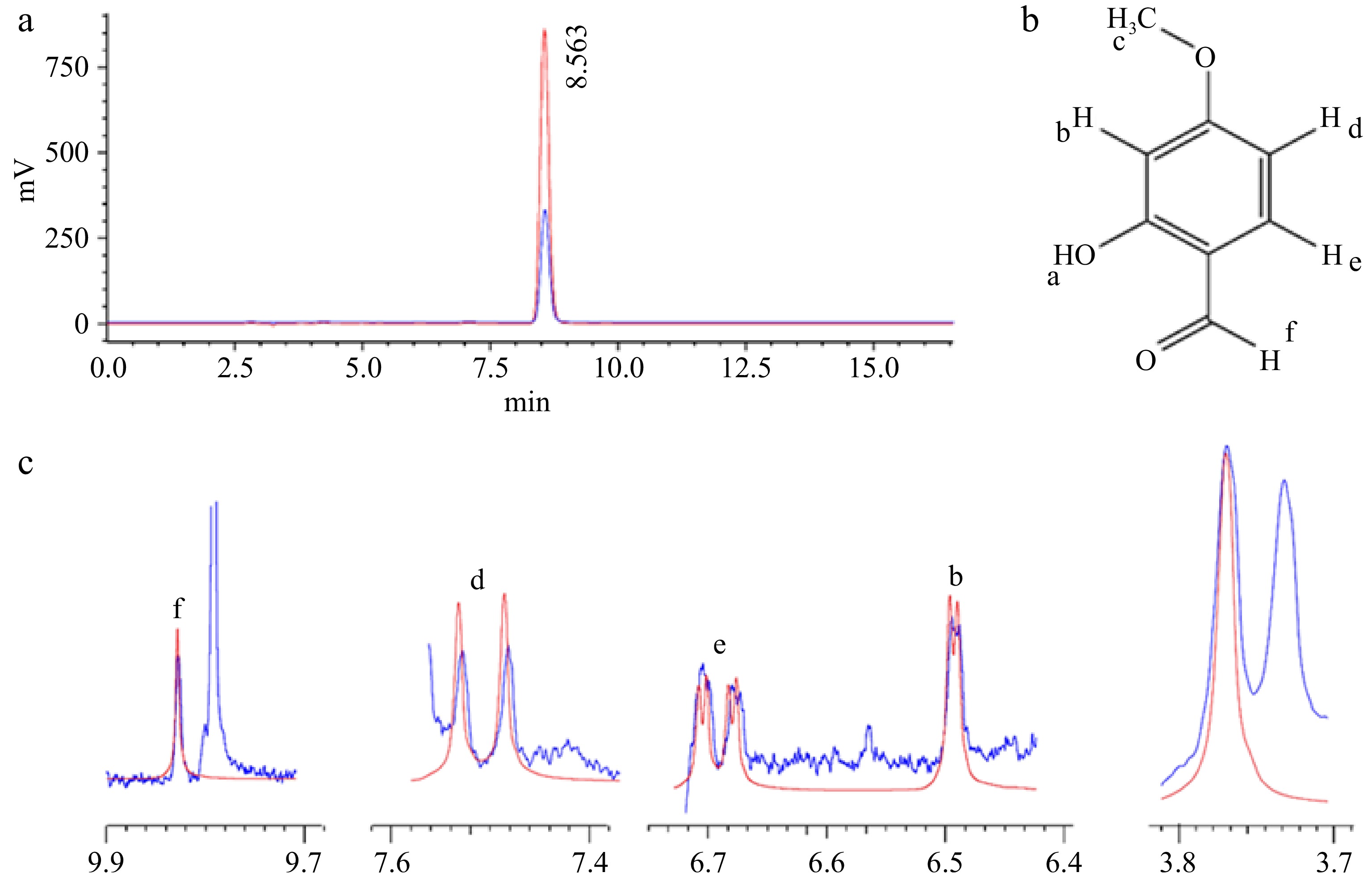

The quantification of 2H4MB in the microcapsule was determined using HPLC and confirmed by 1H-NMR through a chemometric approach. The concentration of the metabolite in the sample was determined by comparing the peak area with the standard 2H4MB concentration (Fig. 1). The 1H-NMR spectral 2H4MB standards were analyzed, and the peak of each proton resonance was marked. Furthermore, the 1H-NMR spectra of 2H4MB in the microcapsules were determined and overlaid with the sample spectra, confirming the standard presence of all peaks, which, in turn, confirmed the presence of 2H4MB in the microcapsules (Fig. 1). The encapsulation efficiency (EE) of different carrier materials was measured to determine the proportion of bioactives surrounded by the wall materials. The presence of surface bioactives on the powder can render it susceptible to oxidation, which, in turn, affects the powder's quality. Table 3 shows the EE% of different carrier materials, which varied between 59% and 82%. SC, along with its blends MS and AS, showed high encapsulation efficiency, followed by the other carrier materials AC, MDX, and MA. Casein, a milk-derived protein, offers high efficiency due to its rapid wall formation and strong emulsifying properties, resulting in excellent encapsulation efficiency[35−38]. In a comparison study, milk protein was reported to be more suitable for the microencapsulation of phenolic compounds because of its higher EE% than gum arabica and maltodextrin[39,40].

Figure 1.

HPLC and 1H-NMR spectra of the vanillin flavor molecule 2H4MB. A: HPLC chromatogram of the standard (red) and the spray-dried sodium caseinate sample (blue). B: Structure of 2H4MB. C: Overlay of the 1H-NMR spectrum of the standard 2H4MB and the spray-dried sodium caseinate sample (lowercase letters b, d, e, f indicate functional groups).

Table 3. Characteristics of spray-dried powder prepared with different carrier materials.

SI. No. Carrier material Carrier material ratio Encapsulation efficiency % Particle size (µm) Flow properties 2H4MB Phenolics flavonoids CI HR 1 MDX 1:0 67 ± 0.4bc 70 ± 0.1c 72 ± 1.1b 11.1a 31c 1.43c 2 AC 1:0 71 ± 0.2bc 62 ± 1.1b 62 ± 0.2a 15.3c 32c 1.47d 3 SC 1:0 82 ± 1.2d 74 ± 0.2d 78 ± 1.3c 17.6d 36d 1.56e 4 MA 1:1 59 ± 1.4a 52 ± 0.4a 74 ± 0.4b 14.5c 33c 1.49d 5 MS 1:1 74 ± 0.2e 70 ± 1.4c 62 ± 0.4a 11.2a 23a 1.30a 6 AS 1:1 76 ± 0.2e 64 ± 0.1b 61 ± 0.1a 12.3ab 26b 1.35b Mean values are expressed (n = 3). Different lowercase letters in each column represents statistically significant differences at p < 0.05. MDX, maltodextrin; AC, gum acacia; SC, sodium caseinate; MA, maltodextrin + gum acacia; MS, maltodextrin + sodium caseinate; AS, gum acacia + sodium caseinate. The powder yield after spray-drying ranged from 33% to 60% (w/w). The spray-dried samples with MDX showed the highest yield (60%), while AS showed the lowest yield (33%). The variation in the yield with different carrier materials may be caused by differences in the materials' properties. The differences in yield can be attributed to the variations in their glass transition temperatures. The conception of using the glass transition temperature (Tg) to understand microcapsule formation, i.e., drip-drying in a spray dryer, was reported by Adhikari et al[9]. In spray-drying, the higher yield of powder can be observed when the droplets' surface is entirely nonsticky when the Tg of the surface layer is more than the droplets' temperature (Td), i.e., ΔT ≥ 10 °C (ΔT = Tg − Td). When the Tg of the droplet surface is less than the droplets' temperature (Td), this results in low yield or uneven drying. The droplets' surface was shown to stick as soon as its surface Tg was greater than or equal to the droplets' temperature (Td)[9]. In addition, the material of the spray-dryer's walls influences the productivity. A study examining the stickiness of the carrier material at various temperatures (20–85 °C) on Teflon, glass, polyurethane, and stainless steel found that Teflon exhibited the lowest stickiness at any given temperature[41]. These aspects play a significant role during encapsulation.

The microbial stability of the spray-dried samples, including bacteria, coliforms, yeast, and molds, was analyzed, as shown in Table 3. The samples showed no detectable growth of microbes after storage for 90 d at room temperature. This may be a result of the antimicrobial properties of the D. hamiltonii extract and the low moisture content maintained during storage[42].

Freeze-drying

-

The aqueous extract of D. hamiltonii was freeze-dried with different carrier materials. Freeze-drying involves milder processing conditions and low temperatures, which results in higher retention of bioactive compounds[25]. Hence, this method is often reported to be used as a control. The results of freeze-dried samples are tabulated in Table 2. The highest bioactive retention of 2H4MB (75.7 ± 5 µg·g−1), polyphenols (72.2 ± 1 mg·100 g−1), and flavonoids (46.3 ± 0.7 mg·100 g−1) was observed when SC was used as the carrier material. AS was found to be the second-best carrier material for retaining bioactives, with 73.6 ± 1 µg·g−1 of 2H4MB, 62.5 ± 0.7 mg·100 g−1 of phenolics, and 52.7 ± 1.1 mg·100 g−1 of flavonoids. The percentage retention of 2H4MB compounds in terms of the extract content in different microcapsules in decreasing order was SC (18.5%), AS (18%), AC (17.5%), MA (17.3%), MS (16.3%), and MDX (15.4%). However, in terms of the percentage of total phenolic content retained, the extracts were in the following decreasing order: SC (34.3%), AS (29.7%), MS (27.6%), AC (23.5%), MA (18.5%), and MDX (16.7%). Similarly, the flavonoid content was in the following order: AS (50.1%), SC (44%), MS (41.5%), MA (41%), AC (23%), and MDX (23.7%). The variation can be attributed to the change in the drying properties with the different carrier materials. The powder yield after freeze-drying was in the range of 92%–97% (w/w). Among the carrier materials MDX showed the highest yield (97%), and AC gad the lowest (92%) yield. The loss in the yield can be caused by the hygroscopic nature of the carrier material, which makes the powder stick to the sample plates in a freeze-drier. The highest retention of bioactives was observed in SC; this may be because of its high solubility, good emulsifying, and gelation properties[41]. Sodium caseinate, when mixed with other carrier materials, exhibited a synergistic effect in encapsulating bioactives with both MDX and AC. Both MDX and AC showed increased bioactive retention when mixed with SC than when used alone. SC is reported to be the most suitable carrier material for microencapsulating phenolics and secondary metabolites of plants[43,44].

The microbial stability of these freeze-dried samples using different carrier materials is presented in Table 3. The freeze-dried samples were analyzed for bacteria, coliforms, yeast, and molds immediately after drying and after 90 d of storage. It was observed that no detectable growth of these microbes was observed; this may be because of the antimicrobial properties of the D. hamiltonii extract[42].

Antioxidant activity

-

D. hamiltonii aqueous extract has been reported to be rich in polyphenols and antioxidants[1,2]. In the present study, encapsulation of these bioactives through spray-drying and freeze-drying was achieved. The methanol extract of these spray-dried and freeze-dried samples with different carrier materials showed antioxidant activity, as determined by measuring their total antioxidant potential, free radical scavenging activity, and reducing power (Table 2). The total antioxidant activity of the encapsulated samples was determined using the phosphomolybdate assay. The microcapsules made with the AS carrier material showed the highest total antioxidant activity in freeze-dried samples (163.6 ± 1 mg·g−1) and the SC microcapsules in spray-dried samples (131.3 ± 2 mg·g−1). Similarly, the reducing potential in methanol extract was assessed by the FRAP method, which revealed that microcapsules made with AS showed the highest reducing power among the freeze-dried samples (143.3 ± 4 mg·g−1) and SC microcapsules among the spray-dried (88.6 ± 2 mg·g−1) samples. The H+ radical scavenging is a vital aspect of an antioxidant assay, which was measured by the DPPH assay. In the DPPH assay, the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) value was observed to be low for samples encapsulated with SC as the carrier material in freeze-dried (23.3 ± 0.7 mg IC50 mL−1) and spray-dried (37.7 ± 1 mg IC50 mL−1) samples, exhibiting strong antioxidant properties. The other microcapsules with different carrier materials in the study showed lower activity. The higher retention of bioactives, i.e. flavors and polyphenols, was achieved in microcapsules made with SC as the carrier materials and in its combinations, AS and MS. Similar observations have also been reported, where protein-based wall materials show high antioxidant potential[14,17,35]. The protein in the carrier material plays a crucial role in protecting the microcapsule by forming a physical wall-like layer around it, which leads to the retention of bioactives in the core. These bioactives inside the microcapsules have functional groups like hydroxyl groups and often produce free radicals such as O2, H2O2, OH, and NO, which have redox potential, and thus show high antioxidant potential. Methods like the reduction of Mo(VI) to Mo(V) and Fe(III) reduction are indicators of electron-donating activity[45], whereas DPPH accepts an electron or an H+ to be converted into a stable diamagnetic molecule and is commonly used as a substrate to determine antioxidant activity[46]. A lower IC50 value indicates higher antioxidant activity. Earlier reports have demonstrated that extracts possess antioxidant activity, primarily because of their rich content of polyphenols and other phytochemicals[2,47]. Extracts with high antioxidant potential can reduce oxidative stress, serve as a source of nutraceuticals, and have potential food applications.

Moisture content

-

Moisture is a crucial parameter for powder products, as it indicates the residual water content in the sample. Samples having a moisture content of less than 10% are considered to be microbiologically stable[24]. The kind of carrier material used has a role in determining the moisture content of the spray-dried product[5]. The moisture percentage of the freeze-dried and spray-dried samples is shown in Table 2. In spray-dried samples, the moisture content ranged between 3.3% and 4.3% (dry basis) in different carrier materials. In the present study, protein-based carrier materials (sodium caseinate) showed a higher moisture content than carbohydrate-based carrier materials (maltodextrin). Similar observations were reported during the spray-drying of blackberry juices[15] and S. stricta aqueous extracts. The moisture percentage in freeze-dried samples ranged from 6.7% to 7.6% (dry basis). The moisture content of freeze-dried samples was higher than that of spray-dried sample; this is because the freeze-dried samples are 'flakes' and they have a porous surface. Freeze-dried samples are reported to absorb moisture very quickly and easily turn into sticky powder[15].

Color

-

The type of carrier material has a significant influence on the color of the powder. The carrier material's native color, the concentration, and the browning of sugars at high drying temperatures influence powder color[5]. The L* value denotes lightness or darkness, the a* values indicate the red–green color, and the b* value indicates the blue–yellow color[17,19]. The color parameters (L*, a*, and b* values) of the powders produced are shown in Table 2. The L*, a*, and b* values of thespray-dried samples are observed to be higher than those of the freeze-drying samples. This may be caused by temperature differences in the drying methods. The type of carrier material has a significant influence (p < 0.05) on the L*, a*, and b* values of the spray-dried and freeze-dried samples. In spray-drying, SC showed low L*, a*, and b* values, indicating a light appearance, and MA showed high L*, a*, and b* values, with a darker appearance. Similarly, in freeze-dried samples, SC exhibits low L*, a*, and b* values, indicating a light appearance, whereas AS displays high L* and b* values, resulting in a darker appearance.

Particle size analysis

-

The spray-dried powder particle size is an important physical parameter that determines the stability of the functional components. The mean particle diameter of spray-dried microcapsules was determined by the D50 value of the samples (Table 3). In spray-dried samples, the particle size varied with different carrier materials, ranging between 11.1 and 17.6 µm. SC microcapsules (17.6 µm) were observed to be larger, while MDX microcapsules were smaller (11.1 µm) compared with the carrier materials used during the study. These variations could be caused by differences in the molecular size of the carrier material. The molecular size of the carrier material determines the viscosity of the feed, and changes in feed viscosity influence the formation of droplets during atomization. Hence, the particle size of the final product varies with different carrier materials[15,16]. The higher viscosity of SC results in bigger particles.

Flow properties

-

The microencapsulated powder's flow properties can be determined using the CI and HR values. The flow properties of spray-dried samples (Table 3) with different carrier materials did not show very good flow characteristics. In spray-drying, when MA was used as the carrier material (CI of 23; HR of 1.3), it was observed to be the best result during the study, followed by AS (CI of 26; HR of 1.35). The CI values of 5–15 indicates excellent flow, 16–18 is good flow, 19–21 is moderately good flow, 22–35 is poor flow, and 36–40 is very poor flow[15,21]. The particles with low interparticle friction, indicated by the HR values of < 1.25, represent good flow (20% CI) and those with HR values of > 1.5 indicate poor flow (33% CI).

Surface morphology

-

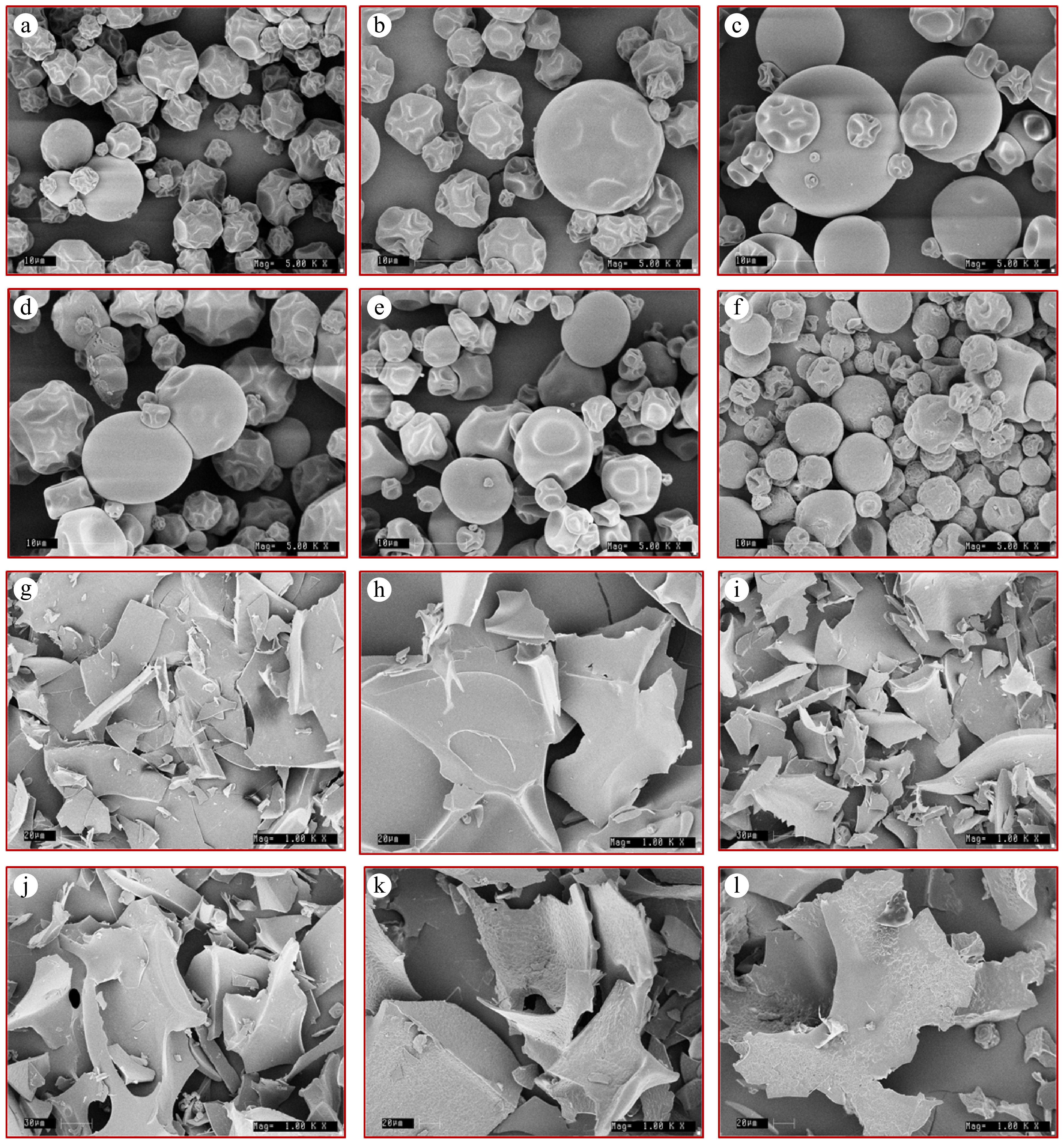

The surface morphology of microcapsules after spray-drying was examined at 5,000× magnification through a scanning electron microscope[24,48] (Fig. 2). In all spray-dried samples, the morphology of the microcapsules was found to be spherical, which is characteristic of spray-dried powders, without cracks, pores, or dents, and irregular ballooning was observed. The absence of pores and cracks on the surface is a vital characteristic that determines the stability of microcapsules. SC and MS microcapsules had as smooth surface morphology, whereas in the remaining microcapsules, surface creases were observed. Microcapsules with a smooth surface are a typical characteristic of SC because of its emulsifying and film-forming properties. The surface creases were attributed to mechanical stresses caused by the droplets' uneven drying at the initial stage[48]. The presence of a smooth, spherical surface is desirable for stable microcapsules, as it facilitates controlled release and improves the effective application in complex food matrices. The surface morphology of freeze-dried samples was observed at 1,000× magnification, and appeared to be larger irregular flakes. The surface morphology of freeze-dried samples varied because of differences in the physicochemical characteristics of the carrier material. The freeze-dried sample of SC appears to have a smooth surface, while in the blends MS and AS, a rough porous surface was observed.

Figure 2.

Scanning electron microscopy images of microencapsulated powder prepared from aqueous extracts of D. hamiltonii tubers. Spray-dried samples at 5,000× magnification: (a) maltodextrin (MDX), (b) gum acacia (AC), (c) sodium caseinate (SC), (d) maltodextrin + gum acacia (MA), (e) maltodextrin + sodium caseinate (MS), (f) gum acacia + sodium caseinate (AS). Freeze-dried samples at 1,000× magnification (g–l): (g) maltodextrin (MDX), (h) gum acacia (AC), (i) sodium caseinate (SC), (j) maltodextrin + gum acacia (MA), (k) maltodextrin + sodium caseinate (MS), (l) gum acacia + sodium caseinate (AS).

FTIR analysis

-

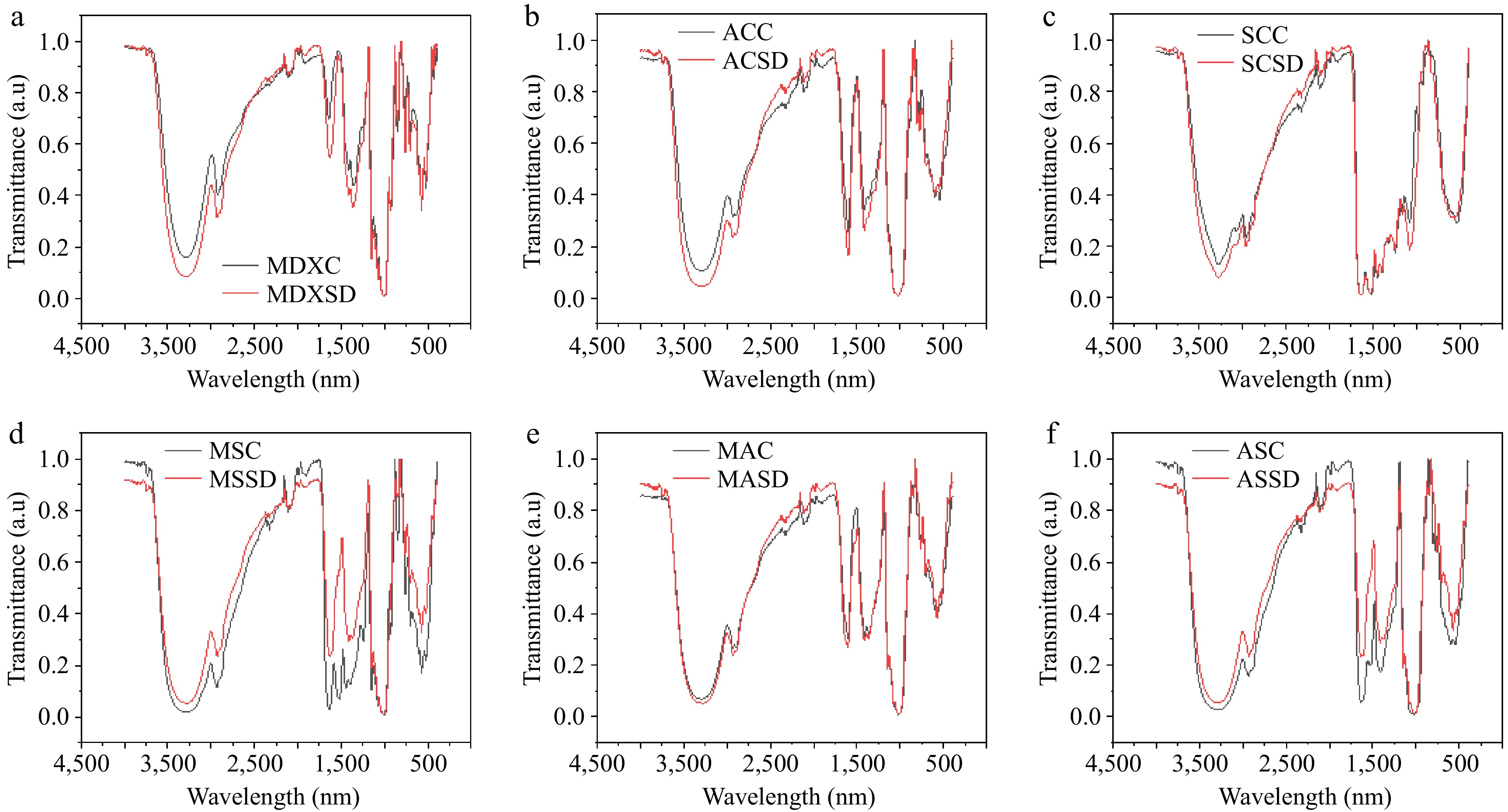

The core wall interaction of spray-dried samples was analyzed using FTIR analysis, which gives insight into changes in the chemical bonds and molecular structure on the wall of microcapsules[15]. The FTIR spectra of spray-dried powder and the carrier materials alone (MDX, SC, AC, along with their combinations) were observed (Fig. 3). In the FTIR spectra, it was observed that no change in the molecular structure occurred at the surface wall of the microcapsule, i.e., the characteristic peaks did not show any shifts in comparison with the carrier materials' spectra, except for the MS and AS spray-dried powders. In the MS and AS spray-dried powder, a change in the spectra was observed at 1,700–1,600 and 1,550–1,480 cm−1. These absorbance spectra represent the amide I and amide II bands of the protein structure. The absorbance at 1,700–1,600 cm−1 represents C=O stretching vibrations of the amide I band, and the absorbance at 1,550–1,480 cm−1 is caused by the C-N stretching and N-H bending vibrations of the amide II band[12]. This change in the spectra was only observed when SC was mixed with other carrier material but not when spray-dried alone. This may be due to the blending of SC (protein) with MDX (carbohydrate) and AC (gum), which showed an interaction with the protein in these spectral regions on the surface wall of the microcapsules.

Figure 3.

FTIR analysis of spray-dried microcapsules. (a) MDXC, maltodextrin carrier material alone; MDXSD, maltodextrin, spray-dried; (b) ACC, gum acacia carrier material alone, ACSD, gum acacia, spray-dried; (c) SCC, sodium caseinate carrier material alone; SCSD, sodium caseinate, spray-dried; (d) MSC, maltodextrin + sodium caseinate carrier material alone; MSSD, maltodextrin + sodium caseinate, spray-dried; (e) MAC, maltodextrin + gum acacia carrier material alone; MASD, maltodextrin + gum acacia, spray-dried; (f) ASC, gum acacia + sodium caseinate carrier material alone; ASSD, gum acacia + sodium caseinate, spray-dried.

Storage

-

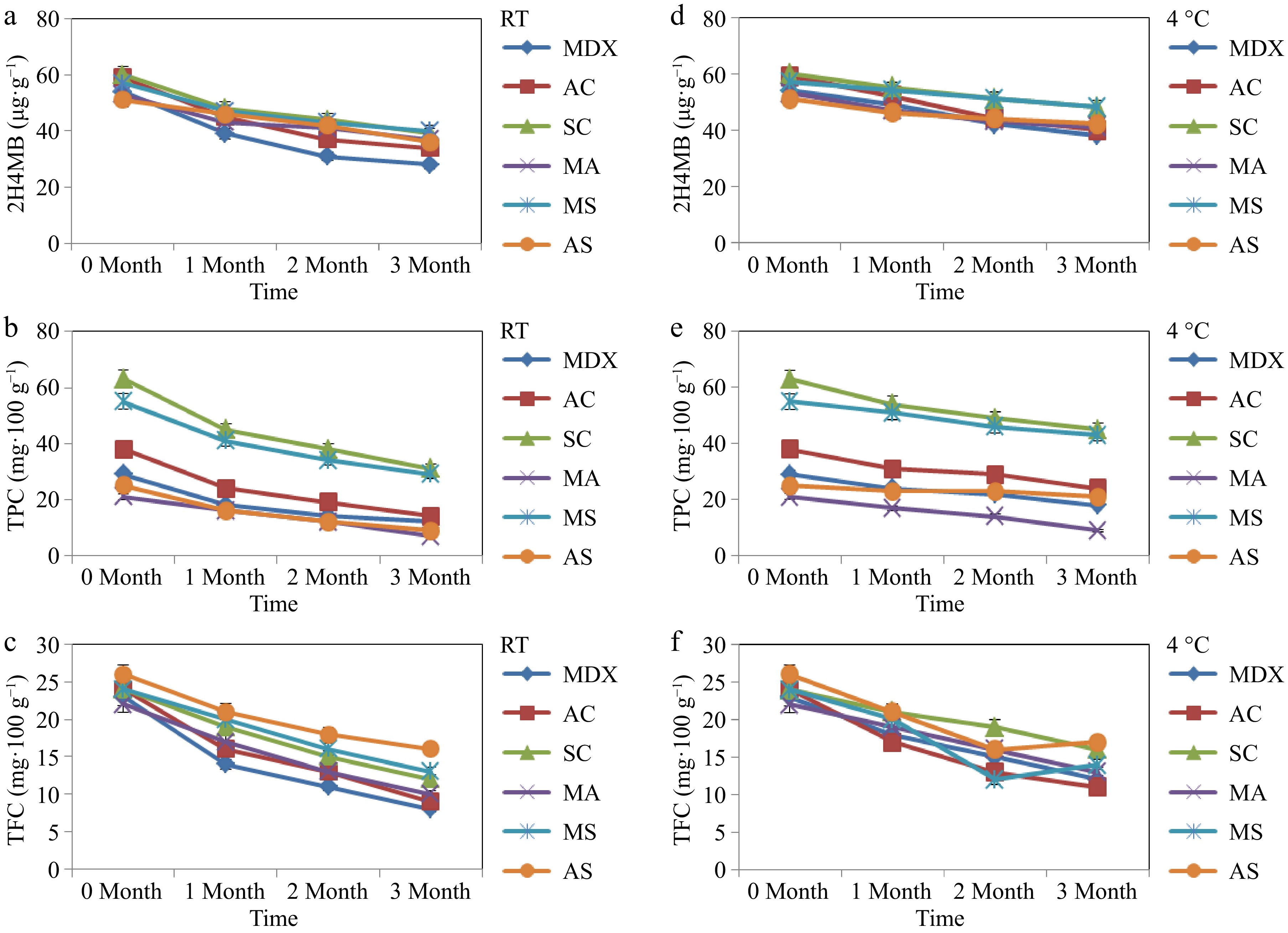

The quantification of bioactives retained in spray-dried powder samples stored at ambient (27 ± 2 °C) and refrigerated conditions (4 ± 2 °C) was determined at regular time intervals (30 d), and the results are shown in Fig. 4. The quantification of 2H4MB, total phenolic content, and total flavonoid content in spray-dried samples was determined over a 3-month storage period (Fig. 4). Microcapsules made of AC, SC, and their combinations (AS and MS) as carrier materials showed good retention of bioactives 3 months in comparison with MDX and MA. Similarly, in a study, the storage of the traditionally used carrier material (gum acacia) and the protein-based carrier material showed high efficiency in the retention of flavor during storage[13]. The amount of 2H4MB in samples stored at 27 ± 2 °C (room temperature [RT]) was 40.7 ± 5 µg·g–1, 39 ± 0.01 µg·g−1, and 36 ± 0.04 µg·g−1 dry powder for SC, MS, and AS, respectively. Whereas the samples stored at 4 ± 2 °C had concentrations of 48.1 ± 3 µg·g−1, 48.3 ± 5 µg·g−1, and 42 ± 0.01 µg·g−1 dry powder for SC, MS, and AS, respectively. During storage at 27 ± 2 °C (room temperature), the samples showed a minimum reduction in 2H4MB (30%) for microcapsules made of MS, and a maximum decrease in flavor was observed for MDX (48%). However, in the samples stored at 4 ± 2 °C, the minimum reduction in 2H4MB (16%) was observed in MS, and the maximum decrease in flavor was achieved by AC (32%). The minimum reduction in flavor in microcapsules made of MS may be caused by the stable combination, in which the carbohydrate in the wall material shields the core from oxidation, and the protein portion maintains the microcapsule's structure[49].

Figure 4.

Storage stability analysis of spray-dried powder. (a) 2H4MB content in spray-dried samples stored at 27 ± 2 °C or room temperature (RT). (b) Total phenolic content (TPC) in spray-dried samples stored at 27 ± 2 °C RT. (c) Total flavonoid content (TFC) in spray-dried samples stored at 27 ± 2 °C RT. (d) The 2H4MB content in spray-dried samples stored at 4 ± 2 °C (refrigerated conditions). (e) TPC in spray-dried samples stored at 4 ± 2 °C refrigerated conditions. (f) TFC in spray-dried samples stored under refrigerated (4 ± 2 °C) conditions.

The total phenolic content in spray-dried samples was determined, and samples stored at 4 ± 2 °C were in the following descending order: SC > MS > AC > AS > MDX > MA. The samples which were stored at 27 ± 2 °C (RT) are in the following order: SC > MS > AC > MDX > AS > MA. In samples stored at 27 ± 2 °C (RT), the minimum reduction in total phenolic content was observed in microcapsules encapsulated with MS (47%) and the maximum reduction was seen in AC (64%). Whereas in the sample stored at 4 ± 2 °C, the minimum decrease in total phenolic content was observed in microcapsules encapsulated with AS (16%), and the maximum reduction was seen in MA (57%).

Similarly, the total flavonoid content in the spray-dried samples stored at 4 ± 2 °C was in the following order: AS, SC, MA, MS, MDX, and AC. Whereas, at 4 ± 2 °C, the total flavonoid content was in the following descending order: AS, MS, SC, MA, AC, and MDX. In the samples stored at 27 ± 2 °C (RT), the minimum reduction in flavonoid content was observed in AS (38%) and the maximum decrease in MDX (48%). In microcapsules stored at 4 ± 2 °C, maximum reductions in flavonoid were seen in MDX (65.2%) and the minimum reduction in SC (33%). The efficiency and stability of microcapsules during storage are reported to be largely dependent on the composition of the carrier material[34]. Factors such as temperature and oxygen conditions are reported to influence the storage stability of microcapsules after spray-drying. The effect of temperature on the storage of spray-dried microcapsules was explained by the glass transition temperature (Tg) of their carrier materials. It is well known that the stability of dried samples increases when the temperature difference between Tg and Ts (Ts is the storage temperature) is significant (ΔT = Tg − Ts). The ΔT is higher in samples stored at 4 °C compared with the samples stored at 27 °C. This may be the reason for the higher retention of bioactives in microcapsules stored under refrigerated conditions[24,50]. Similarly, the bioactives on the wall surface of microcapsules are crucial during storage. Oxidation of these surface biomolecules will lead to the production of off-flavor compounds, which, in turn, affect the product's quality. Therefore, microcapsules with good emulsifying properties entrap molecules in the core material, which may facilitate a longer shelf life. The greater the amount of bioactive compounds entrapped on the microcapsule wall, the higher the possibility of oxidation[10]. Hence, it was evident that the encapsulation of flavor bioactives increases stability and oxidative resistance during storage.

-

In this study, D. hamiltonii extract was successfully microencapsulated for the first time by freeze-drying and spray-drying for food applications. It was evident that the physicochemical characteristics of the carrier material have a significant effect on the retention of bioactives during drying and protection against losses during storage. In the present study, it was observed that milk-based protein as the carrier material showed good efficiency and, when blended with other materials, displayed a synergistic effect. Sodium caseinate, in combination with maltodextrin at a 1:1 ratio, was observed to be a suitable carrier material for the microencapsulation of Decalepis hamiltonii extract, considering its efficiency, yield, and powder characteristics. Since spray-drying-based microencapsulation is a continuous and cost-effective process, it can also be employed for D. hamiltonii bioactives in food and nutraceutical applications. Natural flavor extract powder with antioxidant potential from swallow root is a new value-added product that can serve as an alternative to synthetic vanillin. The encapsulated powder, because of its unique flavor and ease of application, can be used in multiple food formulations as a seasoning; in powdered beverages, powdered soups, sauces, and stock cubes; and in bakery products, cosmetics, and dairy products.

The authors thank the Director, CSIR-Central Food Technological Research Institute (CFTRI), for the infrastructural facilities at the institute and are grateful to CSIR, New Delhi, for funding (CSIR-CFTRI-MLP 251). The authors are also grateful to Mr. S. G. Jayaprakashan and Mr. G. Bammigatti for their support during the spray-drying trials in the pilot plant, Department of Food Engineering, CSIR-CFTRI, and to Mr. K. Anbalagan, CIFS, CSIR-CFTRI, for the support during microscopic analysis. The study was supported by CSIR Government of India, New Delhi for the research Grant MLP 251.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception: Koppada US; Mawale KS; data curation: Mawale KS, Praveen A; formal analysis: Mawale KS; NMR analysis: Praveen A; writing—original draft: Koppada US; supervision, funding acquisition, writing—review and editing: Giridhar P. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of China Agricultural University, Zhejiang University and Shenyang Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Koppada US, Mawale KS, Praveen A, Giridhar P. 2025. Comparative analysis of carrier material efficiency in the encapsulation of flavor bioactives from Decalepis hamiltonii extract by using spray-drying and freeze-drying. Food Innovation and Advances 4(3): 412−422 doi: 10.48130/fia-0025-0045

Comparative analysis of carrier material efficiency in the encapsulation of flavor bioactives from Decalepis hamiltonii extract by using spray-drying and freeze-drying

- Received: 17 December 2024

- Revised: 05 August 2025

- Accepted: 14 August 2025

- Published online: 26 September 2025

Abstract: An aqueous extract from the tuberous roots of Decalepis hamiltonii was encapsulated by spray-drying and freeze-drying for food applications. The study aimed to identify suitable carrier materials among sodium caseinate, maltodextrin, and gum acacia, used alone and in blends, to understand their collective effect during encapsulation. The physicochemical characteristics of freeze-dried and spray-dried samples revealed differences of 14%–20% in 2-hydroxy-4-methoxy benzaldehyde, 12%–40% in phenolic content, and 7%–40% in flavonoid content in the dried powders. Similarly, the methanol extracts of freeze-dried encapsulated samples demonstrated good antioxidant potential compared with those of spray-dried encapsulated powder. Among the carrier materials used, sodium caseinate showed good retention of bioactives and a flavor metabolite (2-hydroxy-4-methoxybenzaldehyde), which was quantified by high-performance liquid chromatography (encapsulation efficiency 82%; yield 40 w/w) and confirmed by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). However, in this study considering flavor retention and powder yield (encapsulation efficiency 74% and 59 w/w), maltodextrin in combination with sodium caseinate (MS) was observed to be the best carrier material for spray-drying. These "maltodextrin–sodium caseinate" microcapsules are stable and show 70% retention of flavor metabolite after 3 months of storage at room temperature, with the microbial load remaining within acceptable limits. The particle size of the carrier materials ranges from 11.1 to 17.6 µm. Thus, the current study suggests that a carrier material mixture (sodium caseinate and maltodextrin) can be used as a prospective material for encapsulating Decalepis hamiltonii bioactives with flavor metabolites and may be useful in food formulations.

-

Key words:

- Antioxidant /

- Flavor /

- Swallow root /

- 2-Hydroxy-4-methoxy benzaldehyde (2H4MB)