-

Plant hormones (phytohormones) are low-abundance endogenous signaling molecules that widely regulate plant growth and development in response to environmental cues. Hormone responses are regulated at multiple levels, including biosynthesis, metabolism, transport, perception, and signal transduction[1,2]. Although most phytohormones are synthesized locally, they often act at distal sites, necessitating the involvement of transporters to mediate their distribution[2,3]. Phytohormone movements occur at various scales, including intercellular (cell-to-cell), intracellular (subcellular), and long-distance (e.g., shoot-to-root and root-to-shoot) transport[4]. In recent years, increasing evidence has highlighted the regulation of plant hormones transport for auxins[5], gibberellins (GAs)[6], cytokinins (CKs)[7,8], ethylene (ETH)[3], abscisic acid (ABA)[4], jasmonates (JAs)[9,10], brassinosteroids (BRs)[2], strigolactones (SLs)[2], and salicylic acid (SA)[11]. In addition, small peptides, often termed 'peptide hormones', act at very low concentrations to regulate interorgan communication, plant developmental processes, and long-distance signaling, highlighting their emerging role alongside classical phytohormones[12,13].

Proteins involved in phytohormone transport include members of several transporter families, such as ATP binding cassette (ABC)[14−23], the nitrate and peptide transporter family (NPF)[24−26], multidrug and toxic compound extrusion (MATE)[27,28], purine permease (PUP)[29−31], equilibrative nucleoside transporters (ENT)[32−34], and the sugars will eventually be exported transporter (SWEET) family[35] (Table 1). Among them, ABC transporters, named for their ability to use energy derived from ATP hydrolysis to move substrates across cellular membranes, are widely involved in multiple phytohormones transport[36−39]. The ABC transporter family is divided into eight subfamilies (A–G and I), and several of the ABC subfamilies have been characterized to transport plant hormones. For instance, ABCC transporters ABCC1 and ABCC2 mediate the vacuolar sequestration of ABA conjugates ABA-glucose ester (ABA-GE)[40], and ABCC4 mediates the efflux of the active CKs to the extracellular space[41]. ABCD1 functions as an importer that transports indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) and JA into peroxisomes[42]. Additionally, two endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-localized ABCI subfamily members ABCI20 and ABCI21 and their homolog ABCI19 contribute to CK transport and response regulation[43].

Table 1. A comprehensive summary of identified phytohormone transporters.

Name Transporter family Identified

substratesTransport direction Subcellular localization Main expression sites Ref. ABCG25 ABCG ABA Efflux PM Leaf vascular vein/root/hypocotyl/endosperm [62,63] ABCG40 ABCG ABA Influx PM Root/leaf guard cells/embryo [65,66] ABCG31 ABCG ABA Efflux PM Endosperm [65] ABCG30 ABCG ABA Influx PM Root/embryo [63,65] MtABCG20 ABCG ABA Efflux PM Lateral root [17] Lr34res ABCG ABA Unclear Unclear Unclear [67] ABCG17 ABCG ABA Influx PM Shoot cortex/leaf mesophyll cells [68,69] ABCG18 ABCG ABA Influx PM Shoot cortex/leaf mesophyll cells [68,69] ABCG16-ABCG25 ABCG ABA-GE Influx PM Unclear [64] ABCC1 ABCC ABA-GE Influx Tonoplasts Unclear [40,80,81] ABCC2 ABCC ABA-GE Influx Tonoplasts Unclear [40,80,81] NPF4.6 (AIT1) NPF ABA Influx PM Seed/vascular of root/leaf/stem [25,126] NPF4.1 (AIT3) NPF ABA Influx PM Unclear [126] NPF4.2 (AIT4) NPF ABA Influx PM Unclear [126] NPF4.5 (AIT2) NPF ABA Influx PM Unclear [25,126] SlAIT1.1 NPF ABA Influx PM Leaf/guard cells/meristem [127] NPF2.12 NPF ABA/GA Influx PM Root meristematic zone/hypocotyl periderm [116] NPF2.13 NPF ABA/GA Influx PM Shoot [116] NPF3 NPF ABA Influx PM Root endodermis [116,128] NPF2.14 NPF ABA-GE/GA Influx Tonoplasts Shoot vasculature/hypocotyl periderm [116] DTX50 MATE ABA Efflux PM Root/leaf/guard cells [27] OsDG1 MATE ABA Efflux PM Node/leaf vascular bundles/rachilla [28] OsPM1 AWPM-19-like ABA Influx PM Vasculature/root tip/guard cells [129] PaPDR1 ABCG SL Efflux PM Root tips/bud/lateral axils [90] MtABCG59 ABCG SL Efflux PM Root/nodule [18] SlABCG44 ABCG SL Efflux PM Root epidermal cells [91] SlABCG45 ABCG SL Efflux PM Root epidermal cells [91] SbABCG36 (SlSLT1) ABCG SL Efflux PM Root epidermal cells [88] SbABCG48 (SlSLT2) ABCG SL Efflux PM Root epidermal cells [88] PUP1 PUP CK Influx PM Flower/leaf margins in hydathodes/mature leaves/major veins/petioles/stem [29] PUP2 PUP CK Influx PM Flower/leaf vascular/major veins/petioles [29] OsPUP7 PUP CK Influx ER Vascular bundle/pistil/stamens [30] PUP14 PUP CK Influx PM Embryo/shoot apical meristem/root [130] OsPUP4 PUP CK Influx PM Vascular tissues [131] OsPUP1 PUP CK Influx ER Root vascular cells [132] PUP8 PUP CK Efflux PM Shoot apical meristem [31] PUP7 PUP CK Influx Tonoplast Shoot apical meristem [31] PUP21 PUP CK Influx Tonoplast Shoot apical meristem [31] OsENT2 ENT CK Influx PM Root [34] ENT3 ENT CK Influx PM Root vasculature [33] HvSWEET11b SWEET CK Efflux PM Nucellar projection/vascular bundle/anther [133] ABCG14 ABCG CK Efflux PM Root pericycle/root vascular tissues/phloem and xylem region of the leaf midrib [19,97,100] OsABCG18 ABCG CK Efflux PM Phloem and xylem region of the leaf midrib [20] ABCG11 ABCG CK Unclear PM Vascular system of root and leaf [101] ABCI19-21 ABCI CK Unclear ER Shoot/root [43] ABCC4 ABCC CK Efflux Unclear Root [41] AZG1 AZG CK Efflux PM Root/flower [134] AZG2 AZG CK Influx PM/ER LR primordia [125,134,135] ABCG6 (JAT3) ABCG JA Influx PM Leaf phloem [103] ABCG20 (JAT4) ABCG JA Influx PM Leaf phloem [103] ABCG16 (JAT1) ABCG JA/JA-lle Efflux/Influx PM/nuclear envelope Vascular tissues of cotyledons [104,122] SlABCG9 ABCG JA Influx PM Red ripe fruit [106] ABCD1 (CTS) ABCD JA precursor( OPDA) Influx Peroxisomal membrane Root/bud/silique/rosette [42] JASSY Unclear JA precursor (OPDA) Efflux Outer chloroplast envelope Unclear [136] PtrOPDAT1 Unclear JA precursor (OPDA) Efflux Plastid inner envelope Leaf/stem (xylem and phloem)/root [137] ABCD1 (PXA1) ABCD Auxin precursors (IBA) Influx Peroxisomal membrane Unclear [138] ABCB4 ABCB Auxin Efflux/Influx PM Root [139,140] ABCB21 ABCB Auxin Efflux/Influx PM Root pericycle/lateral root [139,141] ABCB19 ABCB Auxin/BR Efflux PM Flower/epidermal and mesophyll cells/inflorescence stem/seedling hypocotyl/root endodermal cells [16,45,115] ABCB1 ABCB Auxin/BR Efflux PM Flower/root endodermal cells [5,50,115] ABCB6 ABCB Auxin Efflux PM Leaf/root vascular tissues. [46] ABCB20 ABCB Auxin Efflux PM Root [46] ABCB15, 17, 22 ABCB Auxin Efflux PM Outer tissues of the root meristem/epidermis/lateral root cap [44] ABCB16 ABCB Auxin Efflux PM Outer tissues of the root meristem/epidermis/lateral root cap [44] ABCB18 ABCB Auxin Efflux PM Hypocotyl vascular tissues /mature root tissues [44] ABCG36 ABCG Auxin precursors (IBA) Efflux PM Root epidermal cells/lateral root cap [21,110,142] ABCG37 ABCG Auxin precursors (IBA) Efflux PM Root epidermal cells/lateral root cap [21,142] Long PIN1-4, 7 PIN Auxin Efflux PM Embryo/leaf/root/flower/stem/

root hair cells[124,143] Short PIN5 PIN Auxin Influx ER Hypocotyl/cotyledon vasculature/guard cells/leaf/stem/flower/root hair cells [144] Short PIN8 PIN Auxin Influx ER Leaf vein/ pollen/root epidermal cells/

root hair cells[123] Short PIN6 PIN Auxin Influx PM/ER Flower/shoot/lateral root [145,146] PILS6 PILS Auxin Influx ER Root/cotyledon/hypocotyl [147,148] AUX1/LAX APC Auxin Influx PM Root apical tissues/root epidermal cells [149] WAT1 MSF Auxin precursors (IBA) Efflux Tonoplast Root [150] NPF6.3 (NRT1.1) NPF Auxin Influx PM Shoot/root [151] NPF7.3 (NRT1.5) NPF Auxin Influx PM Root pericycle cells/primary root vascular cylinder/lateral root [26] NPF5.12 (TOB1) NPF Auxin precursors (IBA) Influx Tonoplast Lateral root cap [95] NPF2.10 (GTR1) NPF GA/JA-lle Influx PM Floral organs/shoot/root/around apical meristems/senescent leaves [152] NPF3 NPF GA Influx PM Root endodermis [128] SWEET13 SWEET GA Influx PM Anther/vascular tissues in leaves and roots/axillary buds/embryonic cotyledons [35] SWEET14 SWEET GA Influx PM Anther/vascular tissues in leaves and roots/axillary buds/embryonic cotyledons [35] OsSWEET3a SWEET GA Influx PM Vascular tissue [153] LHT1/2 AAP ETH precursors (ACC) Influx PM Root epidermis/leaf mesophyll [154] EDS5 MATE SA precursors (isochorismate)/SA Efflux Plastid/chloroplast envelope Unclear [155,156] Among the ABC subfamilies, ABCB transporters have been most intensively studied, particularly in relation to auxin transport. They are essential for multiple developmental processes, including lateral root formation, root morphology, hypocotyl elongation, leaf position, and morphology[15,44−46]. Key members such as AtABCB1, AtABCB4, and AtABCB19 contribute to auxin efflux independently, while ABCBs can interact with PIN proteins to mediate auxin polar transport across tissues[47]. Interestingly, ABCB19 not only transports auxin[15], but also functions to maintain BR homeostasis by exporting it[16,48,49]. Recent research has further shown that ABCB1 also acts as a BR transporter[50].

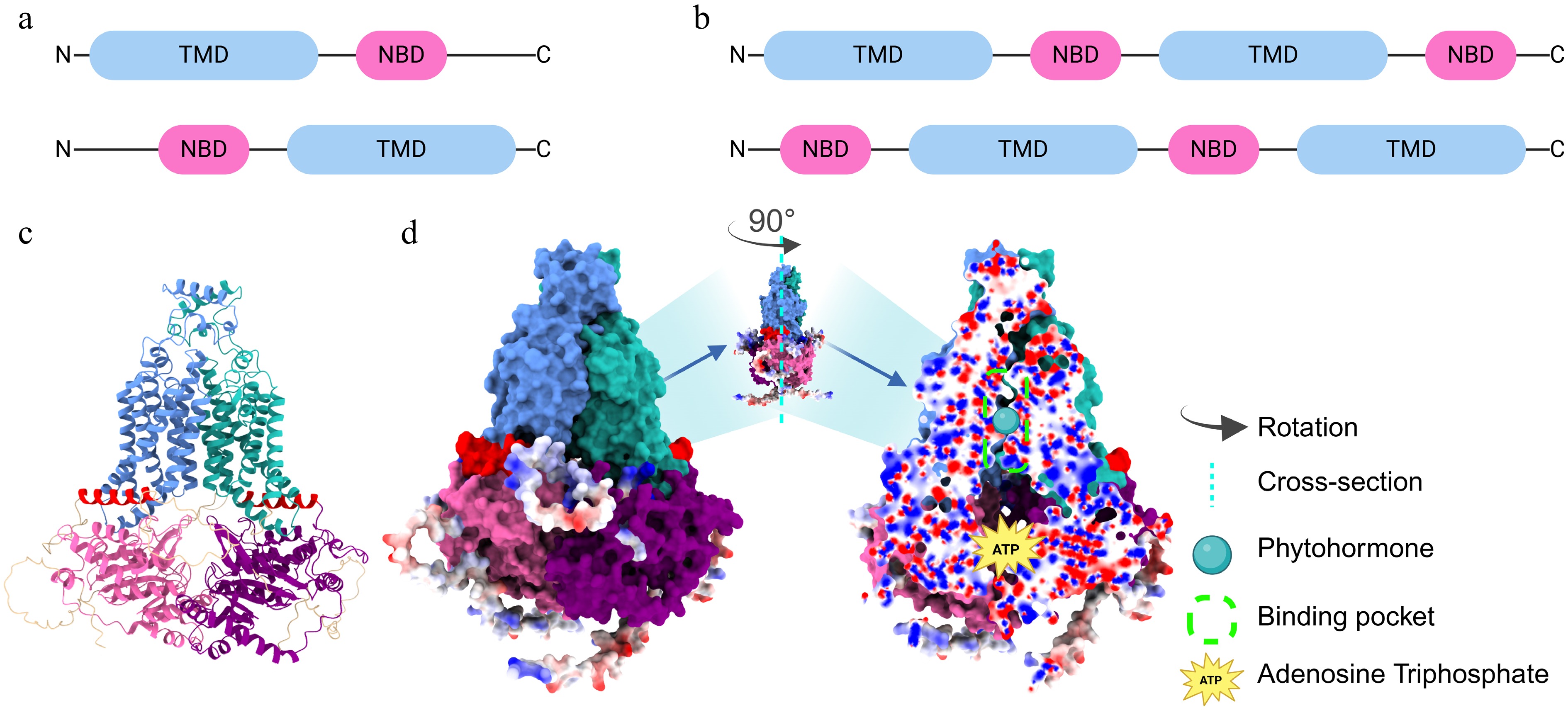

Remarkably, the ABCG subfamily stands as the largest among plant ABC transporters, followed by the ABCB subfamily. In Arabidopsis and rice, the ABCG subfamily comprises 43 and 54 members, respectively[51,52]. ABCG transporters are distinguished by two main domains: the nucleotide-binding domain (NBD) and the transmembrane domain (TMD). The hydrophilic NBD provides energy via ATP binding and hydrolysis, whereas the hydrophobic TMD forms a transmembrane channel and influences substrate specificity[53]. Based on their domain organization, ABCG transporters can be classified into two types: half-size transporters which belong to White Brown Complex (WBC) trandsporters and full-size transporters which belong to Pleiotropic Drug Resistance (PDR) transporters. The half-size ABCG transporters exhibit either a forward TMD-NBD or reverse NBD-TMD arrangement on a single polypeptide chain and necessitate homodimers or heterodimers (e.g., AtABCG14) for functionality. In contrast, the full-size ABCG transporters possess a domain arrangement of forward TMD–NBD–TMD–NBD or reverse NBD−TMD−NBD−TMD and can function independently (e.g., AtABCG36 and AtABCG40)[54−56] (Fig. 1). ABCG transporters are pivotal in precisely governing the spatial and temporal distribution of phytohormones through direct substrate binding and targeted transport[38].

Figure 1.

Structural features of the half-size and full-size ABCG protein. Domain organization of (a) half-size, and (b) full-size ABCG members and their inverted topology. Light blue rounded rectangles represent TMD, while pink ones represent NBD. (c) Structural prediction of the two half-size ABCG proteins using AlphaFold3. The panel shows the predicted 3D structures. (d) Structural prediction of the full-size ABCG protein using AlphaFold3. The left panel shows the surface representations. Color-coding: light sea green/cornflower blue, TMD; pink/purple, NBD; red, coupling helices. Red and blue spheres along the outside of the domains represent dangling amino acid residues. The middle panel shows the full-size ABCG protein rotated 90° counterclockwise to expose the complete binding pocket in longitudinal section. The right panel shows a cross-sectional view of the predicted full-size ABCG structure, showing the hormone-binding and ATP-binding pockets. Red and blue spheres in the cross-section indicate positive and negative electrostatic states, respectively. NBD: Nucleotide-binding domain, TMD: Transmembrane domain.

ABCG transporters exhibit extensive substrate specificity and multifaceted roles in hormone transport[38,39,53]. To date, functional studies have established roles for ABCG transporters in the transport of ABA, CKs, JAs, SLs, and auxin precursors. In contrast, no convincing evidence has yet shown their direct involvement in BRs, SA, GAs, or ETH transport. These latter hormones are included in Table 1 for completeness, as other transporter families (such as ABCB, SWEET, NPF, and MATE) have been identified to mediate their movement. Given the current knowledge and the limited scope of this review, specific focus is placed on the ABCG transporters involved in the movement of ABA, SLs, CKs, JA, and auxin precursors. The subcellular localizations, expression patterns, transport activities, and underlying mechanisms governing these processes are highlighted. Furthermore, this review will explore the identification and characterization of substrates, the functional redundancy observed among ABCG transporters and how to overcome the obscured or masked phenotypic effects observed in single mutants due to functional redundancy among genes, the research methodologies employed in their study, the mechanisms facilitating long-distance transport, and finally, potential perspectives for future research endeavors in this field will be offered.

-

Abscisic acid (ABA), a weak acid, assumes a pivotal dual role in plant physiological processes, encompassing the regulation of seed germination and dormancy, root development, stomatal dynamics, as well as orchestrating responses to both abiotic and biotic stresses[57]. In the context of drought stress, the induction and subsequent transport of ABA across various plant organs are vital for the plant's protective mechanisms[57−61]. Research has demonstrated that, under drought conditions, ABA is predominantly synthesized in leaf guard cells, leaf vascular tissues, and roots, where it exerts its effects either locally or is transported over long distances to induce stomatal closure, thereby reducing water loss[60]. Furthermore, during extended periods of water stress, ABA is transported from the shoot to the root to stimulate root growth, enhancing the plant's ability to access water resources[61].

Subcellular localization, tissue-specific expression patterns and mechanistic insights

-

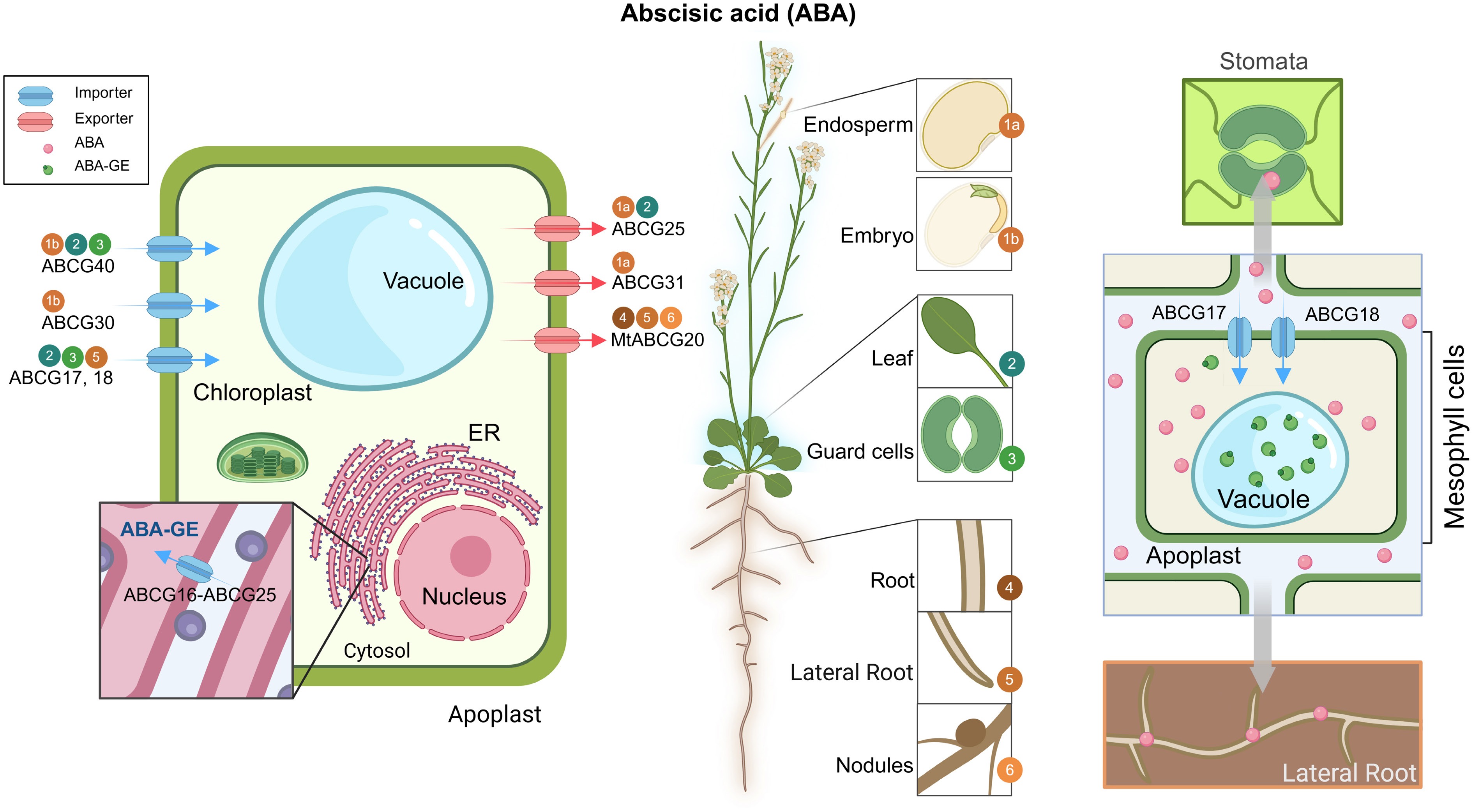

To date, several ABA transporters have been functionally characterized, with ABCG transporters emerging as key players capable of mediating both ABA import and export at the plasma membrane (PM) and endoplasmic reticulum (ER). These transporters are expressed in multiple tissues, including roots, leaves, and seeds (Fig. 2). For instance, ABCG25 functions as a high-affinity ABA exporter, predominantly expressed in the phloem companion cells of the leaf vasculature, where it facilitates ABA transport across the plasma membrane[62,63]. Intriguingly, ABCG25 forms heterodimers with ABCG16 at the ER membrane, promoting the transport of ABA-GE into the ER/nuclear compartment to regulate early seedling growth[64]. Additionally, AtABCG25 cooperates with AtABCG31 to export ABA from the endosperm, a process that significantly affects seed germination[65]. In the embryo, ABCG40 and AtABCG30 work in tandem to import ABA into the embryonic cells[65]. Similarly, MtABCG20, localized to the plasma membrane, serves as an ABA exporter in Medicago truncatula, regulating lateral root development and seed germination[17]. Furthermore, ABCG40, a plasma membrane-localized importer, mediates ABA uptake into guard cells, thereby inducing stomatal closure[66]. Lr34res, a member of the ABCG subfamily in wheat, has been demonstrated to directly transport ABA in both yeast systems and rice (Oryza sativa) seedlings, thereby conferring resistance against multiple fungal pathogens. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying this function remain poorly understood[67]. In addition to intercellular transport, ABA can also undergo long-distance translocation between shoots and roots. Quantitative analyses of ABA levels in both roots and shoots, along with grafting experiments, have demonstrated that ABCG17 and ABCG18 are integral to the long-distance transport of ABA between the shoot and the root to regulate the lateral root formation and stomatal closure[68]. Very recently, ABCG17 and ABCG18 have been further identified as pivotal mediators involved in long-distance ABA transport that affects ABA accumulation in the seed and influences seed size regulation[69]. Additionally, ABCG25 contributes to the long-distance movement of ABA and its conjugate, ABA-GE, from roots to shoots under non-stress conditions, thereby exerting an influence on stomatal regulation. However, its involvement in this process appears to be attenuated under drought stress conditions[63].

Figure 2.

Overview of ABCG transporters involved in ABA transport. A schematic representation of an Arabidopsis plant highlighting major tissues/organs involved in ABA synthesis and transport (middle), accompanied by subcellular localization of characterized ABCG transporters (left) and a simplified mechanism model (right). Blue arrows represent ABA or ABA-GE importers; red arrows indicate ABA exporters. Gray arrows indicate the direction of ABA movement. Numbers in colored circles correspond to tissue-specific expression sites shown in the plant diagram. Most transporters mediate the movement of bioactive ABA unless otherwise indicated (e.g., ABA-GE). All transporters shown were characterized in Arabidopsis thaliana unless a species prefix is provided. ABA, abscisic acid; ABA-GE, ABA-glucose ester; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; Mt, Medicago truncatula.

In crops, especially polyploid species such as soybean and wheat[70,71], gene family expansion has led to a widespread occurrence of gene functional redundancy within the genome[72,73]. This redundancy frequently obscures the phenotypic manifestations caused by single-gene mutations, posing a significant obstacle to the study of gene function and the advancement of breeding programs. To address the challenge of functional redundancy, researchers can employ specialized artificial microRNA (amiRNA) libraries and multi-targeted CRISPR libraries. Each amiRNA or sgRNA is designed to target at least two genes of the same family. These tools enable large-scale gene knockdown or editing, which in turn accelerates research in crop breeding[31,46,74,75]. In the context of the functional genomics of ABCG transporters, evidence of gene functional redundancy has also been uncovered. For instance, ABCG17 and ABCG18 redundantly function in regulating ABA transport to guard cells, as well as at sites of lateral root initiation and during lateral root emergence[68].

Major uncertainties

-

Despite the established role of ABCG transporters in mediating both long- and short-distance transport of ABA, the specific cell types responsible for ABA biosynthesis under normal or stress conditions remain elusive[76]. Moreover, the necessity of intercellular versus long-distance ABA transport for certain physiological processes, such as cortex-mediated root water regulation, warrants further elucidation[77]. Besides, ABA-GE is considered a non-active form of ABA for storage and long-distance transport. It is known to accumulate in vacuoles or the apoplast[78,79]. ABA-GE is typically synthesized in the cytosol and subsequently transported to the vacuole for storage[40]. However, several key aspects of its transport mechanisms remain unclear. For instance, it is not well understood how ABA-GE is transported to the apoplast, how it is loaded into the phloem for long-distance transport, and how ABA generated from the hydrolysis of ABA-GE by BG1 and BG2[80–82] is transported out of the endoplasmic reticulum and vacuole, respectively. These unresolved questions highlight the need for further research to elucidate the intricate pathways and mechanisms involved in the transport and activation of ABA-GE within plant cells and tissues. Additionally, the identity of the protein responsible for transporting the chloroplast-derived precursor xanthoxin to the cytosol remains to be determined[83], as does the transporter that facilitates the movement of ABA aldehyde, the immediate precursor of ABA[84].

Strigolactones

Background

-

Strigolactones (SLs), carotenoid-derived phytohormones, have emerged as key regulators of lateral root development, bud growth, and the establishment of symbiotic relationships between plants and mycorrhizal fungi[85]. SLs can be synthesized in both roots and shoots and play a pivotal role in vascular tissue formation and regeneration by inhibiting auxin PIN-dependent feedback transport[86].

Subcellular localization, tissue-specific expression patterns and mechanistic insights

-

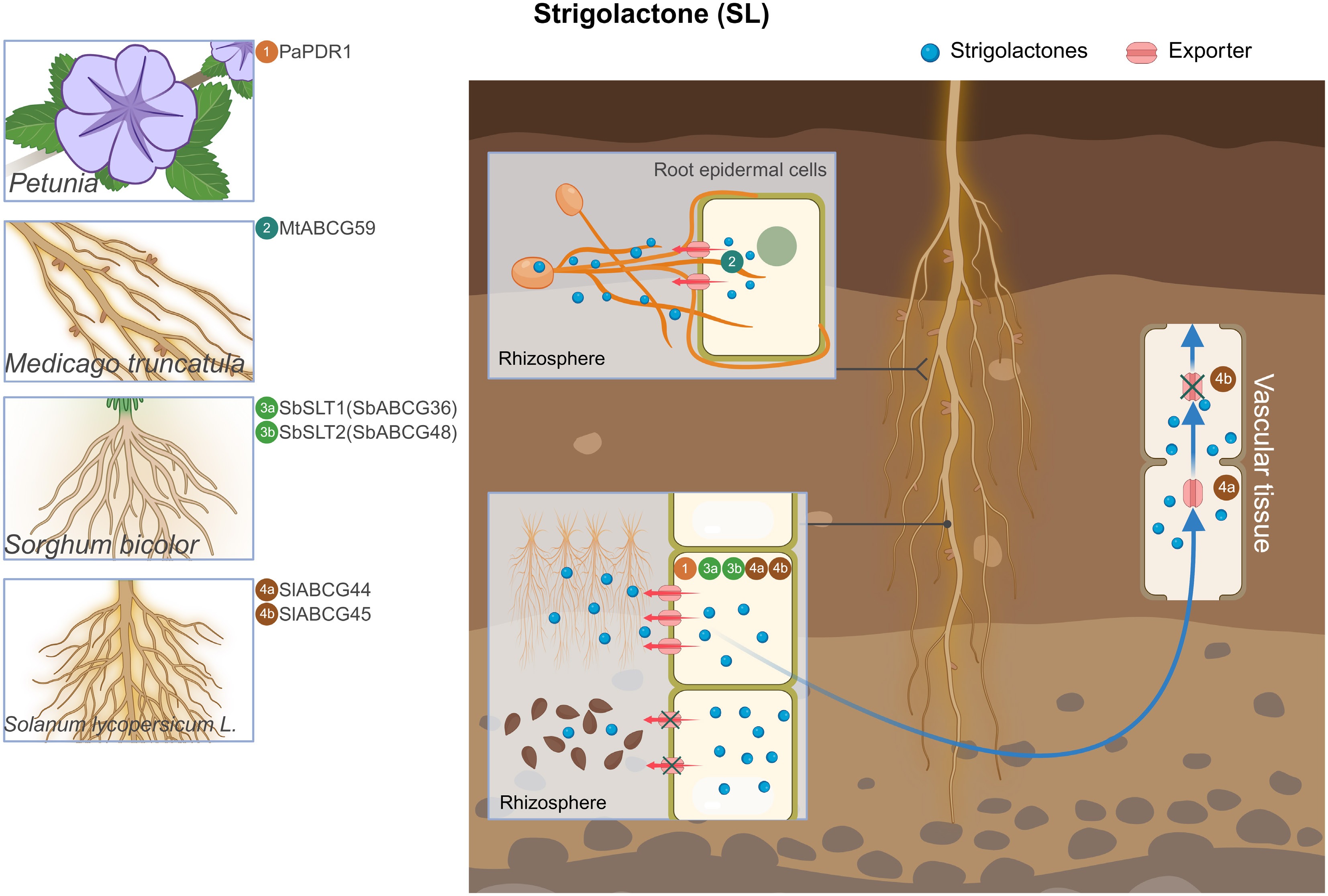

All currently identified ABCG transporters involved in SL transport function as efflux carriers (Fig. 3). The petunia ABCG transporter PaPDR1, the first reported SL exporter, is a PM-located transporter that facilitates the efflux of orobanchol-type SLs into the rhizosphere, a process critical for the development of arbuscular mycorrhizae (AM) and axillary branches[87]. MtABCG59, a homolog of PaPDR1, is specifically expressed in the roots of Medicago truncatula and localized to the PM, where it also mediates the efflux of orobanchol-type SLs and is essential for AM formation[18].

Figure 3.

Overview of ABCG transporters involved in SL transport. Illustration of representative plant species with magnifications highlighting root tissues where ABCG transporters have been characterized. The central root schematic shows SL export sites, with red arrows representing SL export by ABCG transporters. Blue long arrows indicate the direction of ABCG long-distance transport. '×' indicates that ABCG protein transport is repressed. The numbers in circles indicate the names of ABCG transporters. SL, strigolactone; Pa, Petunia; Mt, Medicago truncatula; Sb, Sorghum bicolor; Sl, Solanum lycopersicum.

Beyond dicots, SbABCG36 (SbSLT1) and SbABCG48 (SbSLT2), PM-localized ABCG transporters, represent the first identified SL exporters in monocotyledonous plants. The double knockout of these two genes suppresses Striga seed germination by disrupting SLs transport to the rhizosphere, thereby protecting sorghum growth and yield, indicating functional redundancy between these proteins[88]. Grafting experiments have further demonstrated that root-derived SLs could rescue shoot SLs biosynthesis mutant phenotypes, highlighting the long-distance transport capability of SLs[89,90]. Ban et al. first demonstrated that two plasma membrane (PM)-localized proteins, SlABCG44 and SlABCG45, cooperatively mediate the root-to-shoot long-distance SLs transport. Both proteins also participate in SL exudation from roots, influencing the germination of parasitic plant seeds. Notably, SlABCG45 is highly induced under phosphate (Pi) deficiency, whereas SlABCG44 exhibits weak expression. Only slabcg45 maintains fruit size and weight during development, suggesting functional divergence between the two proteins. Importantly, under low-Pi conditions, SlNSP1 and SlNSP2 were identified as upstream regulators of SlABCG44 and SlABCG45[91]. Collectively, these studies indicate that the ABCG transporters SbSLT1/2 and SlABCG44/45 promote the germination of parasitic plant seeds through a shared SL exudation mechanism conserved across species[92].

Major uncertainties

-

While SL transporters have been identified as exporters, the importers for SLs remain unknown. Despite the identification of several ABCG transporters involved in SLs transport, their substrate-binding ability, binding sites, functional conservation, and upstream regulatory factors are still not fully elucidated. Recent research has applied AlphaFold2 to predict the potential binding sites in the SL transporters ABCG36 and ABCG48[88], but these predictions have yet to be systematically elucidated. Additionally, the mechanism by which SL enters the nucleus remains unclear, a crucial step for its binding to the intranuclear SL signaling receptor D14[93]. It is also uncertain whether other transporter families, beyond ABCGs, contribute to SL transport.

Cytokinin

Background

-

Cytokinins (CKs) constitute a class of plant hormones that play pivotal roles in a wide array of biological processes, including cell division and differentiation, apical dominance, leaf senescence, root nodulation, and nutrient homeostasis. In the shoot, CKs exhibit diverse functions, such as promoting stem and leaf growth, regulating flower development, and influencing fruit maturation[94,95]. Based on the substituent group attached to the nitrogen at the N6 position, natural CKs can be divided into two major types, trans-zeatin (tZ)-type and isopentenyladenine (iP)-type[96].

Subcellular localization, tissue-specific expression patterns and mechanistic insights

-

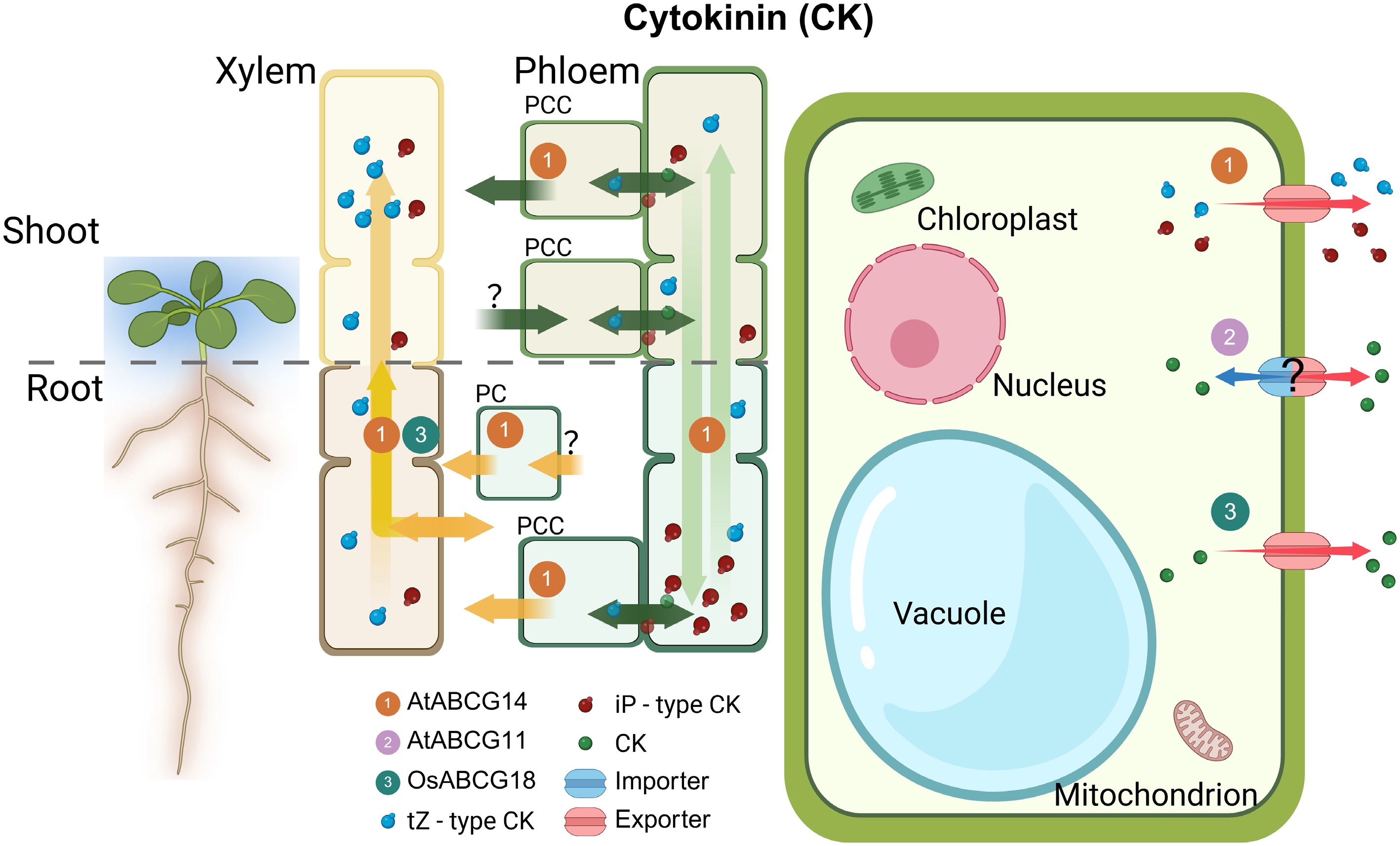

Among the CKs, trans-zeatin (tZ)-type CKs are predominantly synthesized in the root and transported over long distances through the xylem to the shoot. This process is mediated by the plasma membrane-localized transporter AtABCG14, which is expressed in the root[19, 97,98]. Recent findings further revealed that ABCG14 also functions in phloem companion cells, where it facilitates the unloading of tZ-CK into leaf tissues via the apoplast[99]. This suggests that AtABCG14 plays a dual role in mediating both the loading and unloading of tZ-CK during long-distance transport, owing to its spatially distinct expression patterns. In a similar mechanism, AtABCG14 forms homodimers to facilitate the unloading of iP-type CKs in the root, their upward transport to aerial tissues, and subsequent redistribution in phloem companion cells before returning to the root. This underscores the direct involvement of ABCG14 in the long-distance transport of iP-type CKs[100]. OsABCG18, a homolog of AtABCG14, is a PM-localized exporter in vascular cells that mediates the root-to-shoot transport of tZ-type CK by loading them into the xylem. This long-distance regulatory mechanism contributes to enhanced grain yield in rice[20]. Recent research findings have demonstrated that ABCG11 is involved in CK transport and is indispensable for CK-mediated root development[101]. Despite the fact that its subcellular localization during the process of CK transport has yet to be determined, ABCG11 has previously been identified at the plasma membrane, owing to its well-established function in the secretion of cuticular lipid[102] (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Overview of ABCG transporters involved in CK transport. Illustration of ABCG transporters in the plant shoot and root with magnifications highlighting tissues and cells where CK transporters are active. Characterized CK exporters (red arrows) are shown in relevant tissues. Yellow and green long arrows indicate the direction of tZ-type and iP-type CK, respectively. The numbers in circles indicate the names of ABCG transporters. PCC, phloem companion cells; R-PC, root pericycle; ?, unknown mechanism; CK, cytokinin; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; At, Arabidopsis thaliana; Os, Oryza sativa.

Major uncertainties

-

Despite the progress made in identifying key CK transporters such as AtABCG14, significant gaps persist in the understanding of CK transport mechanisms. For example, as CKs have been demonstrated to undergo bidirectional transport between roots and shoots (e.g., via AtABCG14 for iP- and tZ-type CKs[19,97,99,100]), key questions remain as to how root-derived CKs are transferred from the xylem to the phloem in the shoot to enable their redistribution within the plant, and how shoot-synthesized CKs are loaded into the phloem for downward transport to the root. Moreover, CKs exist in multiple forms, and previous research has shown that AtABCG14 is capable of transporting both tZ- and iP-type CKs, likely through a similar mechanism. However, it remains unclear whether AtABCG14 exhibits differences in binding affinity or transport efficiency between these two CK types. In addition, it is yet to be determined whether other CK transporters possess a similar 'dual transport capacity' or instead show selective specificity for particular CK forms. Whether such specificity is related to the expression pattern or tissue localization of these transporters also warrants further investigation. Ultimately, elucidating the mechanisms by which different transporters selectively load or unload CKs at the tissue and cellular levels will be crucial for advancing the understanding of the CK transport network.

Jasmonic acid

Background

-

Jasmonates (JAs) were initially identified as cis-jasmone from the oxidation products of fatty acids in 1957. They are also aromatic components of the essential oil derived from Jasminum grandiflorum. The biosynthesis of JAs occurs in peroxisomes, chloroplasts, and cytosol, and their main bioactive form is JA-Ile[10]. JAs play crucial roles in both developmental processes and stress responses, encompassing root and floral development, wound response, and biotic stress response[103].

Subcellular localization, tissue-specific expression patterns and mechanistic insights

-

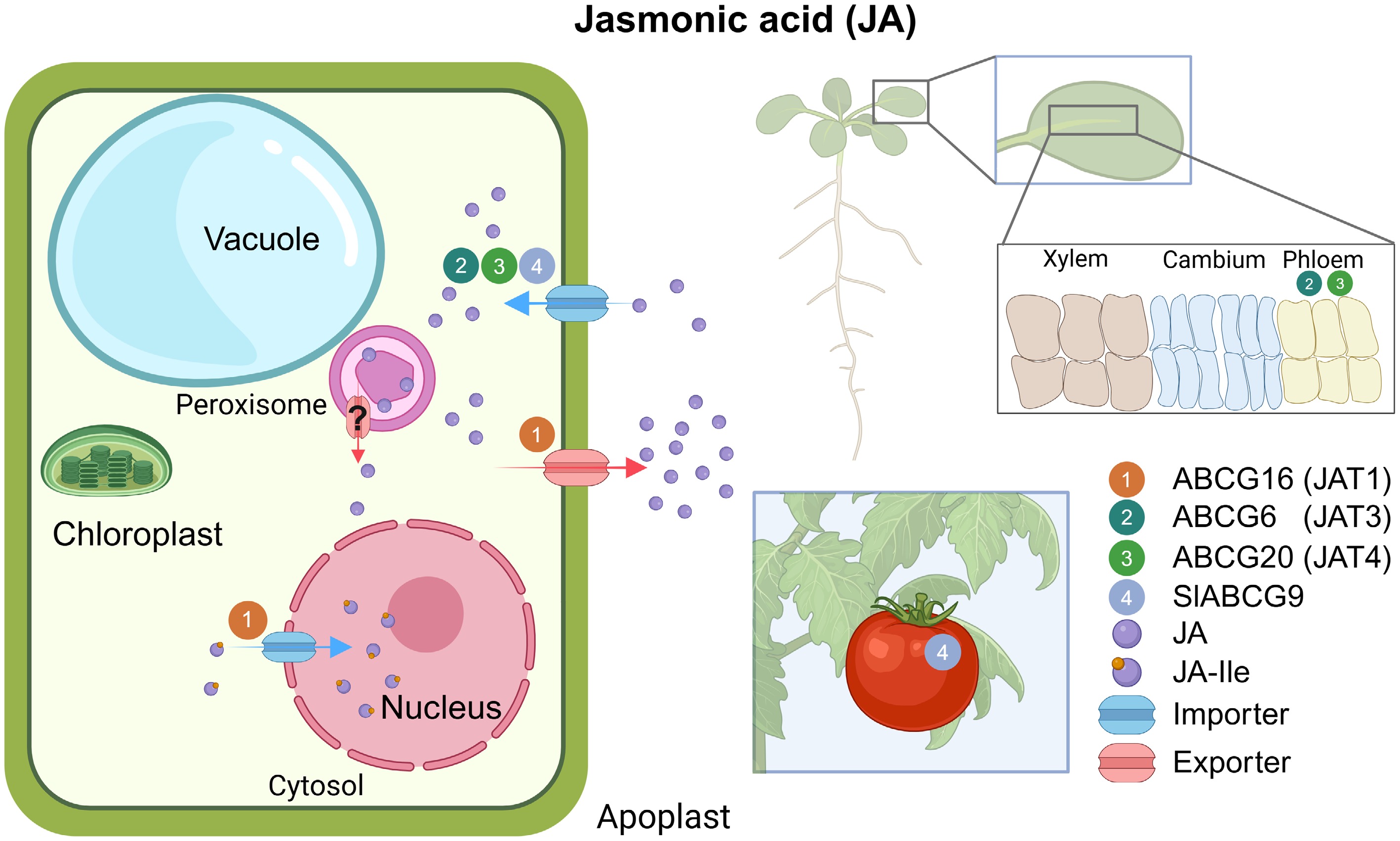

In Arabidopsis thaliana, several ABCG members (AtABCG16/AtJAT1, AtABCG6/AtJAT3, and AtABCG20/AtJAT4) have been confirmed as JA transporters in mediating JA translocation between leaves[9] (Fig. 5). Among these transporters, ABCG16 exhibits dual localization at both plasma membrane (PM) and nuclear envelope, and this characteristic modulates the cellular output of JA and intracellular nucleus input of JA-Ile[104,105]. In the meantime, PM-localized and phloem-expressed ABCG6 and ABCG20 are implicated in wound-triggered systemic resistance through promoting JA long-distance transmission from local leaves to distal leaves[103]. Similarly, PM-localized SlABCG9 serves as a JA importer to improve fruit disease resistance against Botrytis cinerea in tomato[106].

Figure 5.

Overview of ABCG transporters involved in JA transport. (Left) Illustration of intracellular JA transport. (Right) Schematic of tissue expression of JA transporters. The numbers in circles indicate the names of ABCG transporters. Inset boxes are magnifications of the indicated tissues. Blue arrows represent importers; red arrows represent exporters. All transporters were characterized in Arabidopsis unless the transporter name begins with a species abbreviation. ?, unknown mechanism; JA, jasmonic acid; JA-Ile, jasmonoyl-isoleucine.

Major uncertainties

-

JA biosynthesis occurs in the peroxisome; the mechanism by which it is transported out of the peroxisome after synthesis remains unclear. JAT transporters are crucial for the intracellular distribution of JA, bridging the gap between JA biosynthesis and signaling pathways distributed across different cellular compartments. For instance, AtJAT1 facilitates the entry of JA-Ile into the nucleus and the export of JA from cells, providing a novel pathway for JA signaling coupled with its cellular export. Further characterization of other JATs localized to the peroxisome may unveil additional details of the transporter-based regulatory network. Moreover, elucidating the substrate specificity of these JATs, the direction of transport, and their localization to different organelles or membrane structures remains among the most challenging questions in this field[9].

Auxin precursors

Background

-

Auxin, one of the best-characterized plant hormones, is involved in nearly all aspects of vegetative and reproductive development, including plant architecture, organ patterning, vasculature development, and tropic responses to light and gravity[107,108]. Indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) is a precursor of auxin, which plays a crucial role in various aspects of plant growth and development, including root formation and tissue differentiation.

Subcellular localization, tissue-specific expression patterns and mechanistic insights

-

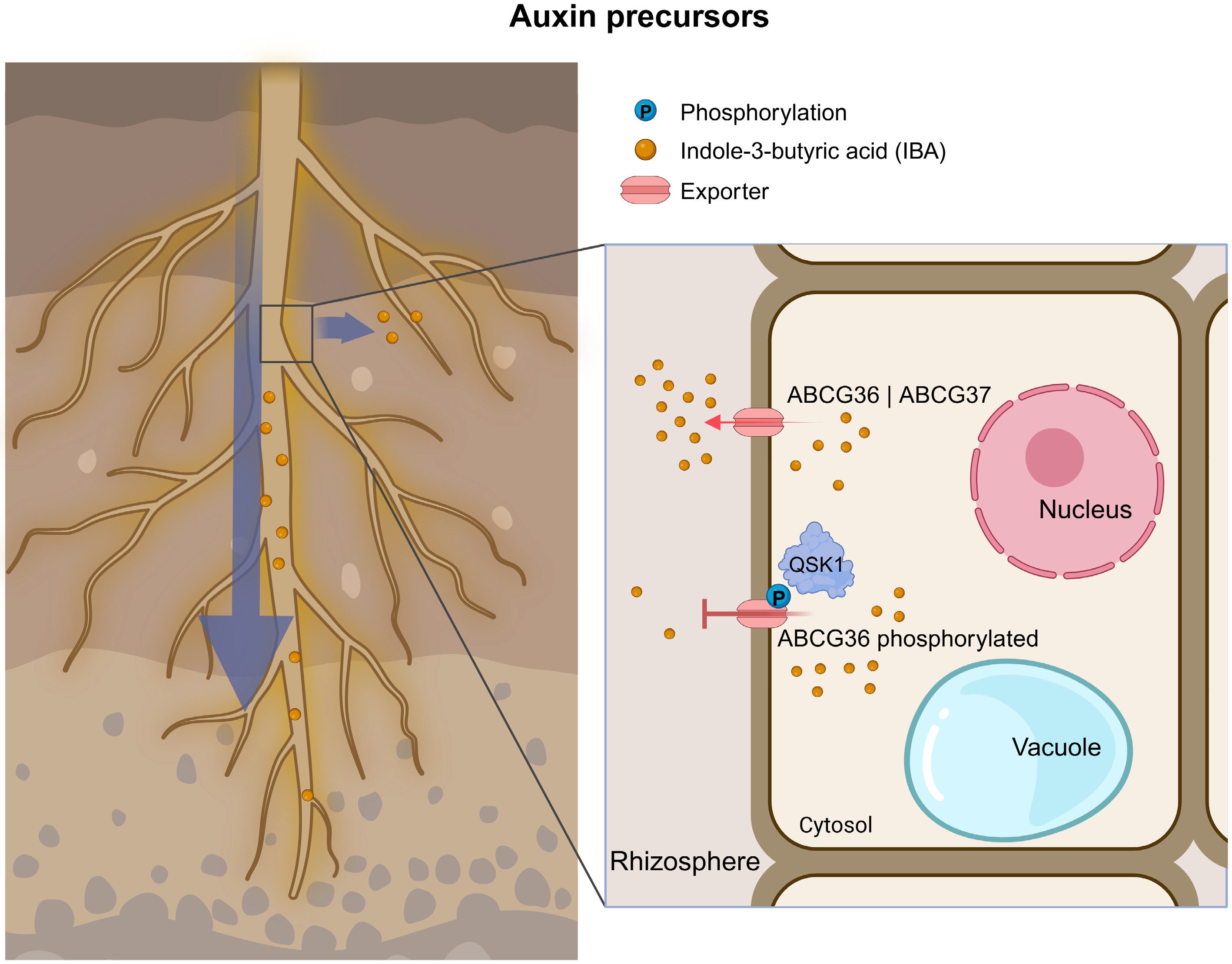

Members of the ABCG family, specifically ABCG36 and ABCG37, along with plasma membrane-localized transporters from the ABCB, PIN, and AUX/LAX families, play crucial roles in regulating polar auxin transport over long distances[108]. However, unlike these classical auxin transporters, ABCG36 and ABCG37 function specifically as exporters of the auxin precursor indole-3-butyric acid (IBA)[21]. Both proteins are polarly localized to the outer plasma membrane of root epidermal and lateral root cap cells, where they redundantly mediate rootward IBA transport and its efflux into the rhizosphere. This process contributes to auxin homeostasis and the establishment of auxin gradients in the root tip[109,110].

A recent study has further demonstrated that the negative regulator QSK1 inhibits IBA efflux by phosphorylating ABCG36, allowing ABCG36 to export camalexin, ultimately enhancing plant resistance to pathogenic infection[111] (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Overview of ABCG transporters involved in auxin precursor transport. (Left) Illustration of an Arabidopsis root highlighting the spatial context of IBA transport. (Right) Enlarged view of a root cell from the region marked in the left panel, illustrating the subcellular dynamics of IBA export. Red arrows represent exporters. The blue arrow indicates the direction of auxin precursor movement. The long red arrows indicate promotion, red T-shaped lines indicate inhibition, and the blue circle with 'P' represents phosphorylation. All transporters were characterized in Arabidopsis unless the transporter name begins with a species abbreviation. IBA, indole-3-butyric acid.

Major uncertainties

-

Despite extensive research on PIN, ABCB, and AUX/LAX auxin transporters, detailed biochemical and biophysical characterizations remain limited, and functional differences among family members require further investigation. Future studies utilizing high-resolution structural techniques such as cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) will be critical for precisely elucidating auxin transport mechanisms[108]. Moreover, it remains uncertain whether ABCG transporters specifically mediate the long-distance transport of IBA between root and shoot via the phloem or xylem. In addition, whether the activities of ABCG36 and ABCG37 indirectly influence the spatiotemporal distribution of IAA, and whether other kinases or transcription factors, beyond QSK1, regulate these transporters, are open questions that warrant further exploration[5].

-

To gain a comprehensive understanding of how plant hormones are transported by specific proteins, various physiological approaches have been employed. These include non-plant heterologous yeast systems, oocyte systems, and Arabidopsis protoplast systems[91]. However, the underlying mechanisms of substrate recognition and transport remain largely enigmatic. The definitive validation of a substrate's identity hinges on a transport assay that unequivocally demonstrates its translocation across a membrane in a strictly ATP-dependent manner. A crucial prerequisite for conducting such an assay is the overexpression of the ABCG transporter under investigation or the generation of ABCG knock-out lines, while carefully selecting an appropriate host[112].

Advances in technology, particularly the application of ATPase assays, liposome reconstitution experiments, microscale thermophoresis (MST), isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, ATPase assays, and cryo-EM[16,50,113], have provided significant support for identifying applicable transporters by analyzing their macromolecule structures from the perspective of transformation sites. For instance, cryo-EM has unveiled the 3D structures of AtABCG25 and ABCG16 in various membrane-spanning conformations. Remarkably, Huang et al. discovered that the substrate-binding pocket of AtABCG16 cannot accommodate ABA, which explains why AtABCG16 mediates JA transport but not ABA transport[114]. MST, ITC, and MD simulations have been utilized to quantitatively analyze the binding affinity between the AUX1 protein and its substrate (IAA) as well as its competitive inhibitor (CHPAA)[113]. These methodologies offer valuable parallels for understanding how ABCB transporters, such as ABCB19 and ABCB1, recognize and translocate BRs across membranes[16,50].

Multifunctional ABCG transporters

-

In addition, ABCG proteins often exhibit the capability to transport multiple substrates. However, to date, no ABCG transporter has been reported to simultaneously transport different classes of phytohormones, but, given the structural diversity within this family, the possibility of multispecificity cannot be excluded. Evidence from other transporter families supports this notion: for instance, ABCB transporters such as ABCB1 and ABCB19 have been demonstrated to concurrently transport both auxin and BRs[15,16,50,115], while members of the NPF family, such as NPF2.12 and NPF2.13, can transport both ABA and GA[116]. Recent studies indicate that the substrate preference of certain ABCB transporters can be switched through phosphorylation mediated by interacting receptor kinases, highlighting an additional layer of regulatory control[111]. These findings indicate that plant hormone transporters can evolve structural features enabling the recognition and translocation of multiple substrates. Although characterized ABCG transporters have predominantly exhibited specificity toward a single hormone or hormone precursor, it is conceivable that structural analyses such as transient access paths, valve-like motifs, and conserved residues within α-helices collectively contribute to substrate specificity. Moreover, external factors, like membrane composition, may also modulate transport activity. Therefore, uncovering how both internal and external factors contribute to substrate specificity is essential for understanding ABCG transporter function[117].

Functional analysis in diverse plant species

-

Most of the current understanding of ABCG-mediated hormone transport primarily stems from studies conducted in Arabidopsis. However, the functions of a limited number of ABCG transporters in phytohormone transport have also been identified in other plant species, including tomato, sorghum, medicago, and petunia. For instance, when comparing the sequences of sorghum's SL exporters, SbSLT1 and SbSLT2, with those of tomato's SlABCG44/45 and medicago's MtABCG59, a conservation of core functional residues is evident, suggesting a shared mechanism for SL export[18,88,91].

Despite this conservation, species-specific differences in the roles of these ABCG proteins are apparent. In sorghum, the sbslt1/sbslt2 double mutant exhibits pronounced resistance to Striga parasitism, indicating a critical role for these transporters in susceptibility to this parasitic weed[88]. In tomato, SlABCG44/45 modulate the number of parasitic weeds by controlling the levels of root-exuded SLs, thereby influencing the plant's interaction with these pests[91]. In medicago, MtABCG59 accumulates in epidermal cells under phosphate starvation conditions, and its knockout mutant displays markedly reduced arbuscular mycorrhizal colonization, highlighting its importance in symbiotic relationships[18]. Collectively, these studies indicate that ABCG proteins involved in SLs transport are generally localized in the root across different plant species and regulate associated biological processes by mediating SLs export. However, whether other ABCG transporters with similar expression patterns, tissue localization, and conserved sequences adopt comparable functional mechanisms remains to be thoroughly investigated.

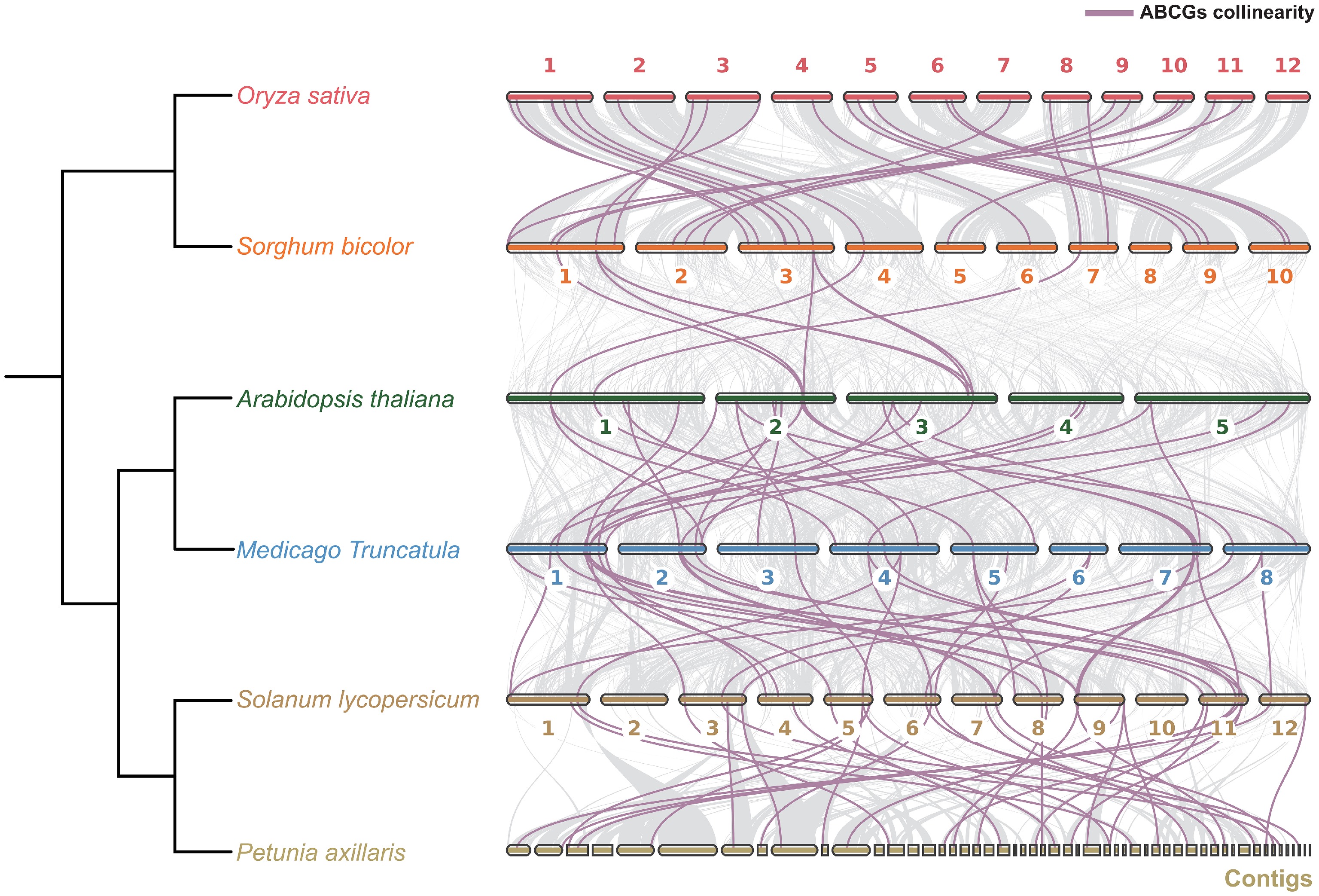

To explore the conservation and divergence of ABCG transporters involved in hormone transport, ABCG homologues in the genomes of multiple plant species were surveyed, including Arabidopsis, rice, tomato, sorghum, medicago, and petunia. Synteny analysis of ABCG genes across different species revealed that the genomic organization of ABCGs remains highly conserved within both monocots and eudicots. Although these two lineages diverged around 130 Mya, a subset of conserved ABCG members has been retained. Meanwhile, with respect to the representative species included in this analysis, substantial differences in synteny were found, both between and within monocot and dicot lineages. Specifically, ABCGs within each lineage (monocots and core eudicots) exhibit strong synteny, whereas synteny between the two lineages is relatively low. This finding suggests that ABCGs may have undergone divergent selection across plant lineages, potentially leading to functional differences. It also implies that the distinct evolutionary strategies of different plant lineages impose varying selective pressures on ABCGs, which could indirectly drive their functional diversification (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Collinearity analysis of ABCG genes across six representative monocot and eudicot species. Purple Bézier curves represent the collinear relationships of ABCG genes across species.

Future research should extend to a broader range of plant species and other types of phytohormones, enabling systematic comparisons of ABCG protein function in different species and different hormone transport processes. Such efforts will be essential for fully elucidating the conserved and diversified roles of ABCG transporters in regulating plant development and environmental adaptation throughout evolution.

Mechanistic insights into hormone transport

-

Despite extensive physiological studies delineating the intercellular and intertissue movement of plant hormones, the molecular principles governing ABCG-mediated transport remain largely unresolved. Key open questions include how ABCG transporters achieve substrate specificity, whether they can translocate both hormones and their conjugated or precursor forms, and to what extent individual transporters accommodate multiple hormone species. If multifunctionality exists, is substrate preference context-dependent, and how is such selectivity regulated? Addressing these questions is essential for clarifying the contribution of ABCG proteins to hormone signaling networks.

In addition to structural elucidation, future endeavors should prioritize the identification of upstream regulatory factors of ABCG transporters. These include transcriptional regulators and post-translational modifications (e.g., phosphorylation, ubiquitination), which modulate their expression, localization, and activity. The downstream signaling pathways that are triggered or influenced by ABCG-mediated hormone export also remain largely uncharted territory. Furthermore, understanding how ABCG transporters integrate or discriminate among hormone signals will be crucial for decoding their physiological roles in development and stress adaptation. Lastly, elucidating the direct structure-function relationship, with a focus on how specific residues or domains contribute to substrate recognition, binding affinity, and translocation efficiency, will be essential for linking structural determinants with transport activity. This will provide a deeper understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying ABCG transporter function and their broader implications in plant biology.

The long-distance transport of hormones

-

In plants, roots and shoots engage in intricate communication to synchronize and optimize growth in response to environmental fluctuations. The autotrophic shoot performs photosynthesis, generating products that sustain root growth. Conversely, the root absorbs water and nutrients from the soil and delivers them to the shoot. This mutual dependence necessitates tight coordination, as alterations in root growth influence shoot development, and vice versa. Such coordination is orchestrated by signal molecules that travel over long distances between shoot and root[1,118,119]. The predominant signals involved in long-distance communication encompass: (i) ABA and CK, which are translocated bidirectionally between root and shoot[63,68,97,100]; (ii) auxin, which predominantly moves from shoot to root[120]; and (iii) SLs, which are hypothesized to be transported from root to shoot via the xylem[89], although the precise mechanisms remain elusive. Investigating the role of ABCG transporters in this process presents two primary challenges: (i) the lack of specific screening systems to identify transporters responsible for mediating long-distance hormone movement, and (ii) technical constraints, as traditional structural biology techniques struggle to resolve high-resolution structures of membrane proteins, thereby impeding a detailed understanding of transport mechanisms. Recent advances in cryo-EM offer a promising avenue to overcome these challenges. Unlike X-ray crystallography, cryo-EM does not require crystallization and is particularly well-suited for studying dynamic and heterogeneous membrane protein complexes[121]. Currently, high-resolution structures of several plant hormone transporters have been resolved, including ABA transporters ABCG25[114], JA transporter ABCG16[122], BR transporters ABCB19 and ABCB1[16,50], auxin transporters PIN1, PIN8, and AUX1[113,123,124], CK transpoter AZG2[125], elucidating their conformational changes and substrate-binding sites. This progress provides a robust structural basis for deciphering the mechanism underlying long-distance hormone transport in plants.

-

Over the past decades, remarkable progress has been achieved in identifying ABCG transporters involved in phytohormone transport and elucidating their mechanisms. This review summarizes the currently characterized ABCG transporters that mediate phytohormone movement, addressing aspects such as transport mechanisms, tissue-specific expression, and subcellular localization. However, research on hormone transport mechanisms remains constrained by limited knowledge of substrate binding sites. While cryo-EM structures have been resolved for a few ABCG proteins—such as AtABCG25—structural information for most members is still lacking. Advanced techniques will be essential to further investigate transporter–substrate interactions. Additionally, the upstream regulatory factors and downstream signaling networks of ABCG transporters are not yet well understood, and their functional diversity and specificity require deeper exploration. Comparative studies across species may provide valuable insights. The complexity of long-distance hormone transport also presents challenges, including the identification of transporters for different bioactive forms of hormones. In the future, the application of advanced genetic and biochemical tools is expected to facilitate the discovery of novel hormone transporters, refine the understanding of phytohormone transport dynamics, and ultimately contribute to crop improvement and sustainable agriculture.

We thank Y Dong (FAFU) for his linguistic polishing of the manuscript. This work was supported by the 'Pioneer Action Plan' Category B of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. 118900M089), and the Self-Deployed Projects of the University of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. E3E46401X2).

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Li Z, Zhang Y; draft manuscript preparation: Li Z; figure preparation: Yu X; manuscript revision: Li Z, Yu X, Zhang K, Zhang Y. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The data supporting the findings and conclusions of this review are derived from previously published studies and publicly available datasets. The references to these sources are provided in the reference section of this article. For any specific data or datasets used in this review, the original sources are cited directly within the text and the table. No new experimental data were generated for this review.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Zhuorong Li, Xikai Yu

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Chongqing University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Li Z, Yu X, Zhang K, Zhang Y. 2025. ABCG transporters in phytohormone dynamics: mechanisms, challenges, and future perspectives. Plant Hormones 1: e021 doi: 10.48130/ph-0025-0020

ABCG transporters in phytohormone dynamics: mechanisms, challenges, and future perspectives

- Received: 07 July 2025

- Revised: 23 August 2025

- Accepted: 02 September 2025

- Published online: 10 October 2025

Abstract: Phytohormones are low-concentration signaling molecules synthesized under controlled conditions. They can exert their effects beyond their site of synthesis to modulate a wide range of developmental processes and responses to environmental stimuli, thereby highlighting the necessity of their transport. ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters are ubiquitous in bacteria, animals, and plants, facilitating the transport of a wide array of substrates. Among them, ABCG transporters constitute the largest subfamily in plants and exhibit the broadest spectrum of hormone substrates. Given their prevalence and crucial role in facilitating the transport of multiple phytohormones, this review specifically spotlights ABCG transporters. These ABCG transporters hold a pivotal position in orchestrating both intercellular and long-distance transport of plant hormones. They are instrumental in the movement of various hormones, such as abscisic acid, strigolactones, cytokinins, jasmonic acid, and auxin precursors. Here, we provide a comprehensive summary of all currently characterized ABCG transporters known to mediate phytohormone transport, covering their transport mechanisms, tissue-specific expression, functional redundancy, and subcellular compartmentalization. Additionally, this review delves into pivotal challenges confronting the field, including the identification of substrates, functional analysis in non-model species, and methodological approaches for probing long-distance transport.