-

Arsenic (As) has attracted widespread attention because of its serious adverse effects on humans, such as skin cancers[1]. Among the various exposure pathways, contamination of water by As is probably the greatest threat, as it poses a significant health risk to human populations through either direct ingestion or indirect food chain pathways[2]. Arsenic enters the surface water by both natural processes, such as oxidative/reductive dissolution of As-bearing minerals, and anthropogenic activities, such as discharge of As-containing wastewater, and eventually accumulates in sediments, resulting in much higher As concentrations than the baseline in sediments[3]. The concern is that As can be released back into the overlying water from sediments in response to changes within the aquatic environment, such as elevated temperatures or reduced oxygen (O2) levels[4,5]. The primary mechanism for the release of As from sediments is widely acknowledged to be the reductive dissolution of As-bearing iron (Fe) or manganese (Mn) oxides[6]. Research has shown that the release flux of soluble As across the sediment interface can reach up to 130.2 ng/cm2/d under hypoxic bottom-water environments, directly elevating its concentration in the overlying water from <10 µg/L to approximately 70 µg/L[7]. Consequently, understanding the potential factors enhancing the As mobilization in sediments is essential for mitigating As contamination risks of water bodies.

Macrophytes, especially submerged species, constitute a vital component of aquatic ecosystems, and their root activities can affect As mobilization in sediments[8]. Macrophytes generally release O2 from their roots into the anoxic sediments, which is referred to as radial O2 loss (ROL)[9]. This process not only directly oxidizes Fe(II) to Fe(III), but also enhances the activity of Fe(II)-oxidizing microbes[10]. Both processes drive the development of Fe plaques on root surfaces, consisting primarily of poorly crystalline Fe minerals including ferrihydrite and lepidocrocite[11], which immobilize As via adsorption and co-precipitation reactions[12]. The ROL-driven As(III) oxidation processes in the rhizosphere, including the chemical oxidation by Mn-oxides[13] and the biological oxidation by those microbes with As(III) oxidase genes (aioA)[9,14], can reduce As mobility and bioavailability, as the oxidation products As(V) can be further sequestered by root Fe plaques.

There has been a substantial decline in submerged macrophytes over the last 40 years, due to human activities and climate change[15,16]. After the death of macrophytes, however, the sediment characteristics are reshaped around the decaying roots[17], which may reverse the rhizosphere sequester mechanism from an accumulation zone to a release hotspot, and thereby become a source of aqueous As contamination. Decaying roots cannot release O2, meaning the subsequent cessation of ROL causes a shift in condition from an aerobic rhizosphere to an anaerobic detritusphere[18]. The reductive dissolution of low crystalline Fe-oxides in the Fe plaque under O2 limitation may be enhanced[19], potentially resulting in the rapid release of As into the porewater[20]. Furthermore, the transition from the rhizosphere to the detritusphere initiates a succession of microbial communities, from those that utilize root exudates for energy to those that specialize in decomposing more refractory organic litter[21]. These changes in microbes could significantly alter As biotransformation processes, thereby influencing its speciation and mobility. For example, As(V)-reducing microbes encoding respiratory As(V) reductase genes (arrA) could reduce As(V) to gain energy under anaerobic conditions[14], further increasing the As mobility. Despite the high risk of As release during the apoptosis of macrophytes, the transformations of Fe and As, and their implications for As mobilization are not well understood, particularly in the context of the global decline in macrophytes[22].

Our limited understanding of As mobilization and transformation in the rhizosphere stems from its steep gradient of chemical, physical, and biological profiles along the millimeter to sub-millimeter scale, especially considering its temporal dynamics[23]. Until recently, research progress has been facilitated by advanced microscale sampling techniques, coupled with a variety of spectroscopic and microscopic techniques[24,25]. Herein, we combined some novel research approaches to unravel the mobilization and transformation processes of As in sediments before and after macrophyte death. Our objectives were to: (i) monitor the spatiotemporal dynamics of As and related parameters by using planar optodes (PO), high-resolution dialysis (HR-Peeper), and the diffusive gradients in thin films (DGT); (ii) investigate the effects of Fe-mineral transformations on As mobility by combining Mössbauer spectroscopy and chemical extraction schemes; and (iii) explore how the structural and functional characteristics of microbiota change and affect As mobilization through high-throughput sequencing and real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), from rhizosphere to detritusphere. The findings are crucial for understanding the potential future threats to sediment As release and associated water contamination risks.

-

Vallisneria natans was chosen as a case study owing to its widespread distribution in global aquatic ecosystems and common application in the field of ecological restoration[26]. V. natans, surface sediments, and water samples were collected from Lake Taihu, China, in June 2022. V. natans was one of the dominant macrophytes in Lake Taihu; however, the area where they grow has been sharply decreased since the 1990s due to water pollution and eutrophication[27]. The basic characteristics of the water and sediment are presented in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2. Sediments were passed through a mesh (150 μm) to eliminate large particles and benthic infauna, and water was filtered through a filter membrane (0.45 μm). Sediments were subsequently placed into 12 Perspex tubes (diameter 11 cm, length 35 cm) and six transparent rhizoboxes equipped with detachable windows (height 25 cm, length 10 cm, width 5 cm).

Two microcosm experiments were set up to study the mobilization processes of As during the transition from the rhizosphere to the detritusphere (Supplementary Fig. S1). In the first microcosm experiment, four Perspex tubes were used as a group to monitor the dynamics in redox conditions and soluble As levels in sediments with root growth and subsequent root degradation. In the second microcosm experiment, two rhizoboxes were used as a group to visualize the two-dimensional (2D) distribution of O2 and labile As within both the rhizosphere and detritusphere. For both first and second microcosm experiments, triplicate experiments were performed. To ensure consistency in the experimental material, young V. natans with an aboveground length of approximately 10 cm were selected for incubation. Their roots were cut to retain only about 1 cm in length before transplantation.

For the first microcosm experiment, Perspex tubes were incubated in a water tank maintained at 25 °C. The light conditions consisted of an intensity of 180 μmol photons/m2/s, with a light:dark photoperiod of 12:12 h. Two young V. natans were transplanted into the one Perspex tube and allowed to grow for 45 d to obtain a dense root system. Following this growth period, the aboveground parts were cut off to simulate plant wither[18], and further incubated for at least 15 d until roots showed significant degradation. In total, four sampling times were set up, each using three Plexiglas tubes. For the second microcosm experiment, rhizoboxes were incubated in a water tank at 25 °C (Supplementary Fig. S1). The temperature and light conditions were consistent with those used in the first experiments. Two young V. natans were transplanted into transparent rhizoboxes and positioned at a 45° angle to ensure that the roots developed along the detachable side[18]. To avoid interference from DGT sampling on the rhizosphere environment, the same rhizoboxes were not chosen to compare the differences between the rhizosphere and detritusphere. Plants were first allowed to grow for 20 d, and then the aboveground parts were cut off and further cultivated for at least 15 d until roots showed significant degradation. Rhizoboxes have a smaller volume compared to Perspex tubes, and therefore the growth period of V. natans was adjusted to 20 d to avoid the dense root systems.

Microelectrode and HR-Peeper measurement

-

In the first microcosm experiment, the vertical profiles of dissolved O2 (DO) and redox potential (Eh) in sediments were determined at unplanted stage (0 d), growth stage I (15 d), growth stage II (45 d), and decomposition stage (> 60 d) by using a microelectrode system (Unisense, Denmark), with the probe positioned near the plant to capture the impact of root growth and degradation on sediment redox conditions. Sediment porewater was sampled using HR-Peeper samplers (EasySensor Ltd., China). This sampler operates on the principle of diffusive equilibrium between sediment porewater and deionized water in the sampler chamber[28]. At different stages, HR-Peeper samplers were inserted into the sediment near the plant and left to equilibrate for 72 h. Soluble As, Fe, and UV254 in the porewater were subsequently analyzed with a spatial resolution of 5.0 mm. UV254 absorbance, a well-established proxy for aromatic dissolved organic matter (DOM)[29], was utilized to monitor root decomposition dynamics in this study (Supplementary Fig. S2).

PO and DGT measurement

-

In the second microcosm experiment, the PO and DGT techniques were employed for mapping O2 and labile As in sediments. PO is often used for measuring the temporal and spatial distribution of solutes in sediments via luminescence imaging of sensor films that contain fluorophores[30]. In this study, O2 optodes were attached to the detachable windows, and luminescence image acquisition was performed daily using PO2100 imaging systems (EasySensor Ltd., China) to monitor the dynamic changes in O2 from rhizosphere to detritusphere. The PO2100 imaging system integrates two 405 nm light-emitting diodes (LEDs), a complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor camera, and an embedded controller for synchronized light source and image acquisition management. A 460 nm long-pass filter was installed on the camera lens to reduce the interference of light. All image capture procedures were completed within a darkroom environment.

DGT, an in situ passive sampling technique, can obtain the labile fractions of solutes, including free ions, the weakly-bound fractions that can be released from complexes and solids[31]. The combination of DGT and laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA ICP-MS) enables the mapping of 2D distributions of various solutes in sediments[32]. HR-ZCA DGT was utilized to visualize the distribution of labile As, Fe, Mn, P, and S(-II)[33]. Following O2 imaging, the detachable windows equipped with O2 optodes were replaced with HR-ZCA binding gels immobilized with polyvinylidene fluoride membranes and sealing tape, and deployed for 24 h.

After retrieval, DGT gels were vacuum-dried at 50 °C for 3 h. The quantitative analysis of multiple elements using LA ICP-MS was performed according to previously established methodology[33]. Laser ablation of dry DGT gel was performed using Resolution LR/S155 LA system equipped with Coherent Compex-Pro 193 nm ArF excimer laser, with aerosolized samples transported through He gas to the Agilent 7700 × ICP-MS to obtain the signal intensities of the target solute. The scanning speed, laser spot size, acquisition time, repetition rate, and energy output of the LA system were 50 μm/s, 100 μm, 0.006 s, 10 Hz, and 2.5 J/cm2, respectively. As the major elemental component of the matrix of the binding gel, signals for 13C as an internal normalization standard were recorded simultaneously[34]. The spatial resolution of both PO and DGT is 100 µm. The detailed fabrication procedures and processes of the PO and DGT are provided in the Supplementary File 1.

Sample collection and analysis

-

After DGT sampling, root Fe plaques, rhizosphere and detritusphere samples, as well as corresponding bulk sediment, were collected from the rhizoboxes in the second microcosm experiment. To minimize the impact of spatial heterogeneity, the same samples from each rhizobox were thoroughly mixed to form a composite sample. All samples were subjected to freeze-drying and kept at −80 °C until analysis. Each composite sample was analyzed in triplicate. Sediment genomic DNA was extracted using an OMEGA Soil DNA Kit (M5635-02) and subsequently subjected to 16S rRNA gene sequencing. The 515F/907R primer sets (5′-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3′ and 5′-CCGTCAATTCMTTTRAGTTT-3′) were employed to sequence a specific segment of the prokaryotic 16S rRNA (V4–V5 hypervariable regions). Additionally, genes related to As transformation, including As(III) methylation (arsM), As(III) oxidation (aioA), as well as As(V) reduction (arrA and arsC), were evaluated using qPCR[14]. Details regarding the primer pairs for As-cycling genes are summarized in Supplementary Table S3. 16S rRNA gene sequencing and qPCR measurement were performed on the Illlumina NovaSeq platform and LightCycler480II at Shanghai Personal Biotechnology Co., Ltd, China. Detailed sequencing procedures are given in the Supplementary File 1.

Iron mineral transformations from rhizosphere to detritusphere were studied using 57Fe Mössbauer spectroscopy and chemical extraction. 57Fe Mössbauer spectra were recorded at room temperature (295 K) using a proportional counter and Mössbauer Spectrometer (MFD-500AV-02), at the Center for Advanced Mössbauer Spectroscopy, Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Dalian, China). Fe-oxides and other Fe-bearing mineral phases were identified according to their Mössbauer parameters, including isomer shift, quadrupole splitting, and magnetic hyperfine field[35]. A refined extraction method was used to determine Fe speciation, including acid volatile sulfide and carbonate-associated Fe(II), easily reducible Fe oxides, reducible Fe oxides, magnetite, and pyrite−Fe (Supplementary Table S4)[36]. Arsenic speciation was determined using the Shiowatana sequential extraction procedure, including water-soluble As (FS1), surface-adsorbed As (FS2), Fe/Al associated As (FS3), acid-extractable As (FS4), and residual As (FS5) (Supplementary Table S5)[37]. Total Fe and As were extracted by a HNO3–HF mixture. Fe and As concentrations in the extraction were measured using ICP-MS and ICP-atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES), respectively. Recoveries of Fe and As in the certified reference samples ranged from 93% to 108%.

Data analysis

-

The release flux of soluble As across the sediment interface (J, ng/cm2/d) was calculated utilizing data obtained from HR-Peepers in accordance with Fick's First Law[38]:

$ J=-\varphi {D}_{\mathrm{S}}{\left(\dfrac{\partial C}{\partial X}\right)}_{X=0} $ (1) where,

$ \varphi $ $ ({\dfrac{\partial C}{\partial X})}_{X=0} $ For O2 fluorescence images, the red and green channels were extracted to calculate the O2 concentration. The concentration gradient of O2 around roots was used to calculate the ROL per area of root surface (ROL rate)[39]. A thin diffusion layer of 0.10 mm thickness is utilized in the measurement of DGT. Thereby, its results are generally interpreted as representing the time-averaged flux of the analyte (pg/cm2/s)[40]. Detailed data analysis of PO and DGT is provided in the Supplementary File 1.

Amplicon sequences were quality-controlled and analyzed via the QIIME (Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology) platform, version 2. The composition, structure and alpha (α) diversity of microbial communities were assessed using the 'vegan' package in R. The differentially abundant taxa across groups were identified using the linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) through the 'microeco' package in R. The Functional Annotation of Prokaryotic Taxa (FAPROTAX) tool was used to evaluate Fe metabolic functions. Sequence data from this study have been uploaded to the NCBI Sequence Reads Archive (PRJNA1047963).

Correlation analysis was conducted using the Spearman method. Significant differences were assessed using the Mann–Whitney U-test. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 27.0 software.

-

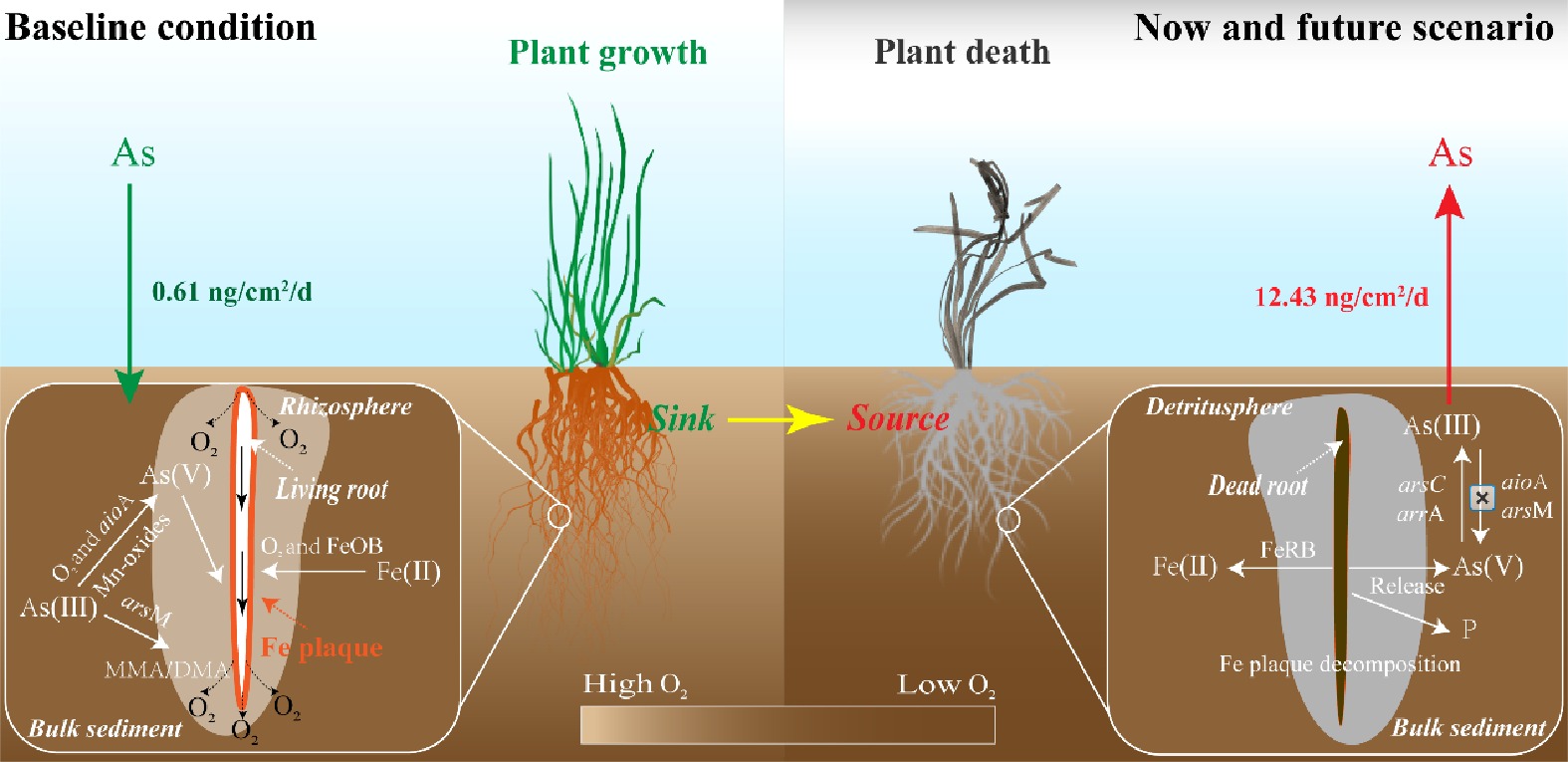

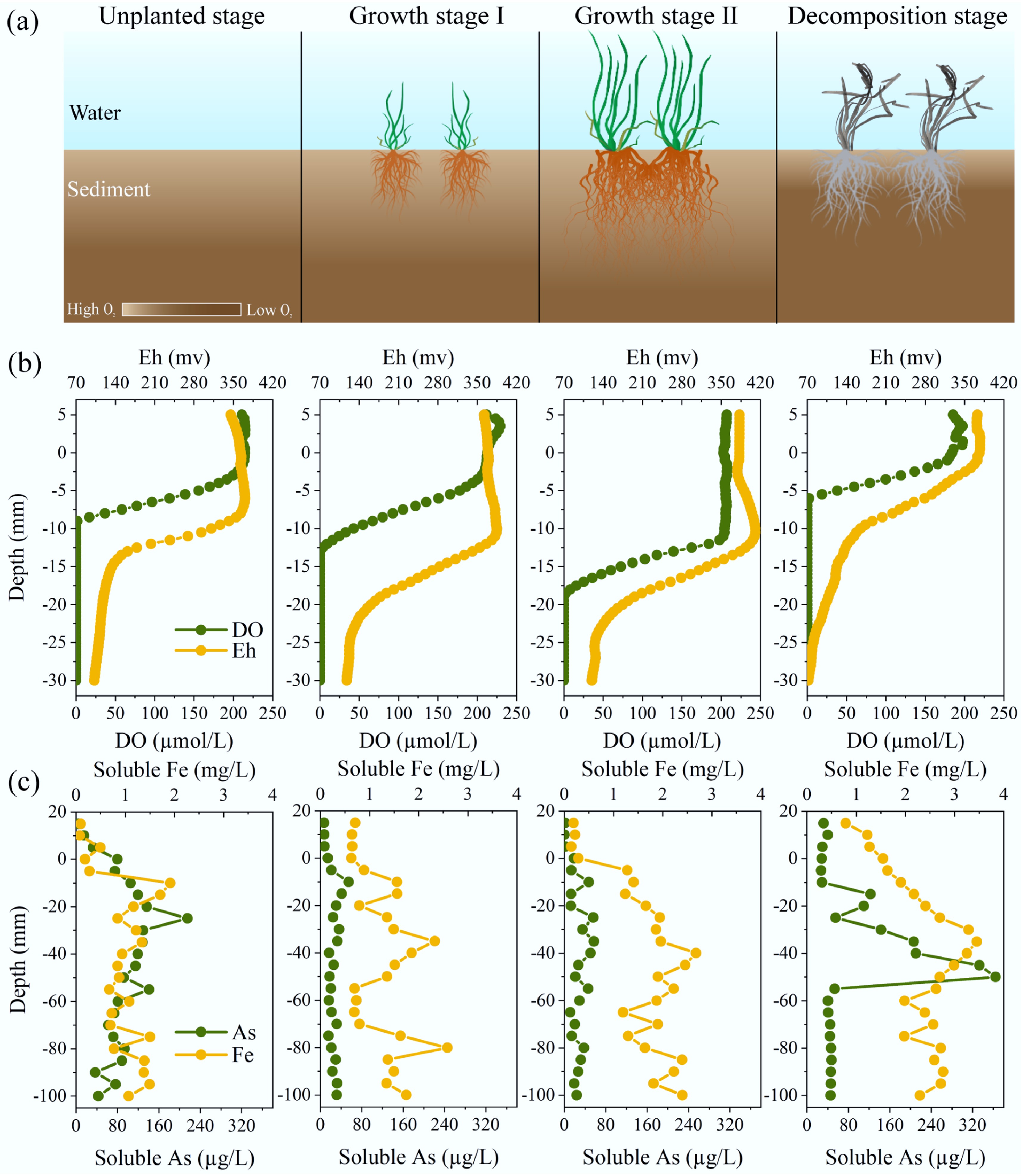

As shown in Fig. 1a, b, the O2 penetration depths were −12.5 and −18.5 mm at the growth stage I and II of V. natans, respectively, which were 3.5 mm and 9.5 mm deeper compared to the unplanted stage. At the root decomposition stage, the O2 penetration depth decreased to −6 mm. The Eh in sediments also exhibited similar changes. Average Eh values in sediments increased from 211.48 to 279.60 mV with the root growth, and decreased to 167.81 mV after the death of plants. Root growth of macrophytes can improve the Eh in sediments, while degradation of macrophyte roots decreases it.

Figure 1.

Changes in physico-chemical properties in sediments during growth and death of submerged macrophytes. (a) Schematic illustration of growth and death of macrophytes, which changes the redox environments in sediments. (b) Vertical distributions of DO and Eh, and soluble As and Fe in sediments. (c) Vertical distributions of soluble As and Fe in sediments.

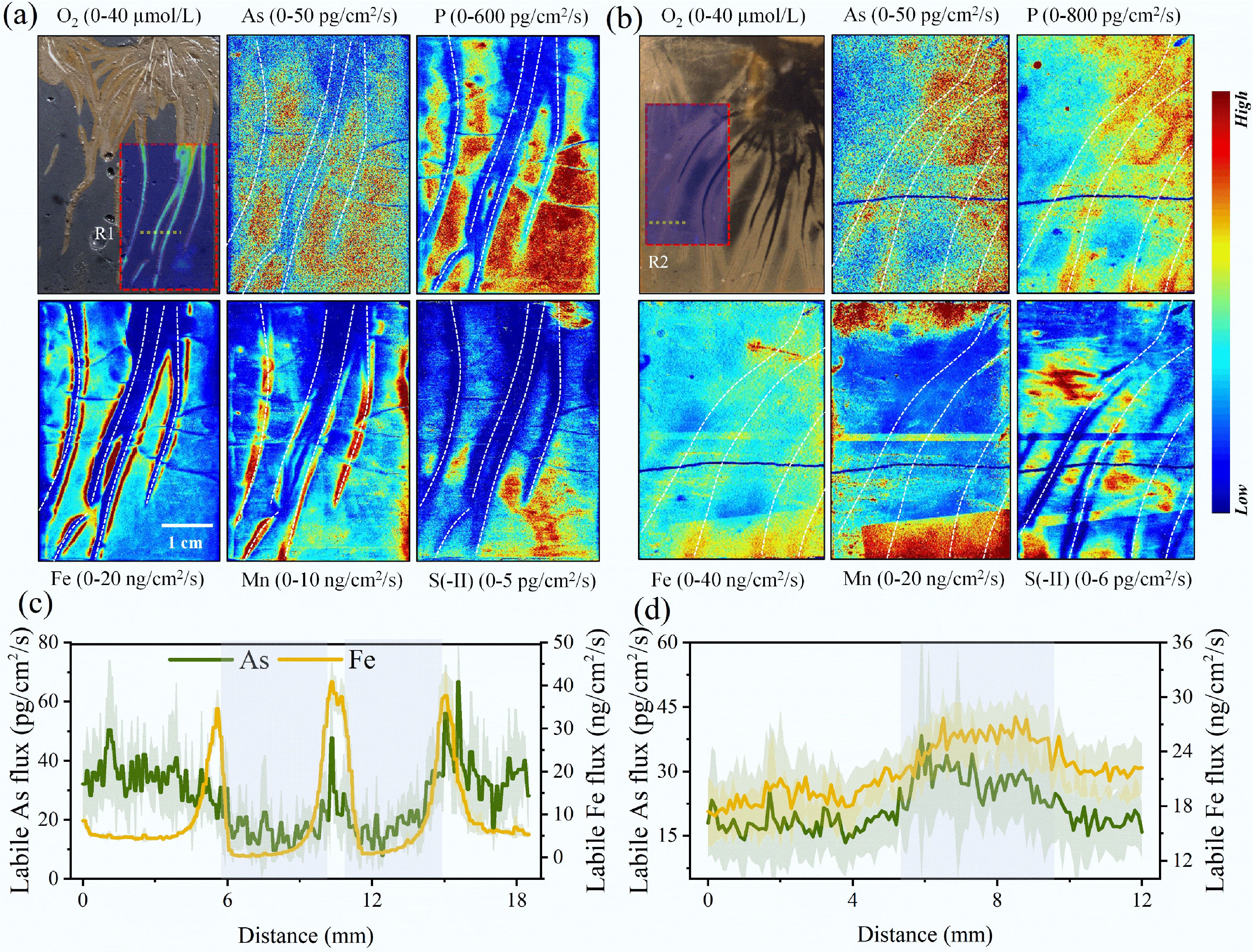

ROL occurred along all visible roots of V. spiralis according to O2 imaging, causing the formation of an oxic area situated about 4–20 mm away from the center of the root (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S3). The O2 concentration was highest in the zones of the root-dense part, and gradually decreased to the root tips. The ROL rate ranged from 2.10 to 35.13 nmol/m2/s, which is comparable to previously reported values (Supplementary Table S6)[41]. After plant death, root O2 release stopped, with the aerobic rhizosphere being transformed into an anaerobic detritusphere (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S3).

Figure 2.

High-resolution imaging of O2, As, and other relevant elements in sediments Two-dimensional distribution of O2 and labile fluxes of As, P, Fe, Mn, and S(-II) in the (a) rhizosphere, and (b) detritusphere. The white dotted lines represent the position of the roots. One-dimensional distribution of labile fluxes of As and Fe in the (c) rhizosphere (R1), and (d) detritusphere (R2), grey areas indicate rhizosphere or detritusphere.

Changes in soluble As in sediments with root growth and degradation

-

The soluble As levels decreased in both the overlying water and porewater during growth of V. spiralis (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. S4). In the overlying water, soluble As concentrations were 7.82 ± 0.34 and 1.40 ± 0.69 µg/L at growth stages I and II of V. natans, respectively, significantly lower than those at the other two stages (p < 0.01). In the porewater, the soluble As concentration during V. natans growth was approximately 3.5-fold lower than that during the period of no growth and withering. Furthermore, the release flux of soluble As decreased from 7.62 to −0.61 ng/cm2/d with the V. natans growth, while it increased to 12.43 ng/cm2/d after the death of V. natans.

Spatial distribution of labile As in the rhizosphere and detritusphere

-

High-resolution chemical imaging showed that the labile As fluxes in all visible rhizosphere were lower than those in the bulk sediments (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S5). Labile As flux was 17.63 ± 4.67 pg/cm2/s in the rhizosphere, less than half that in the bulk sediment (35.88 ± 7.15 pg/cm2/s) (Supplementary Figs S6 and S7). Reduction in labile As within approximately 5 mm of the rhizosphere was observed. After plant death, localized hotspots of labile As occurred, spatially more concentrated around the detritusphere. Labile As flux was 27.54 ± 3.97 pg/cm2/s in the detritusphere, which was significantly greater than that in the bulk sediments (18.05 ± 2.56 pg/cm2/s) (p < 0.01). There was a localized approximate twofold increase in labile As from rhizosphere to detritusphere. Additionally, labile fluxes of Fe, P, and S(-II) also increased from rhizosphere to detritusphere, whereas labile Mn showed the opposite trend (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S6).

Fe and As speciation in the rhizosphere and detritusphere

-

Arsenic and iron enriched in the root Fe plaques, with their content being approximately threefold higher than that in other samples (Supplementary Fig. S8a, b) (p < 0.05). In the Fe plaques, Fe/Al associated As was 10.22 mg/kg, which is approximately tenfold higher than other samples (Supplementary Fig. S8c). The proportions of As fractions in the Fe plaques were FS1 (0.08%), FS2 (0.99%), FS3 (17.50%), FS4 (3.34%), and FS5 (78.09%) (Supplementary Fig. S8d). The FS5 was the dominant fraction of As in other samples, and its proportions exceeded 80%. Furthermore, the labile fraction (FS1 + FS2) was 1.07% in the Fe plaques, which was lower than that in the rhizosphere (4.89%), detritusphere (5.01%), and bulk sediments (4.43% and 6.60%).

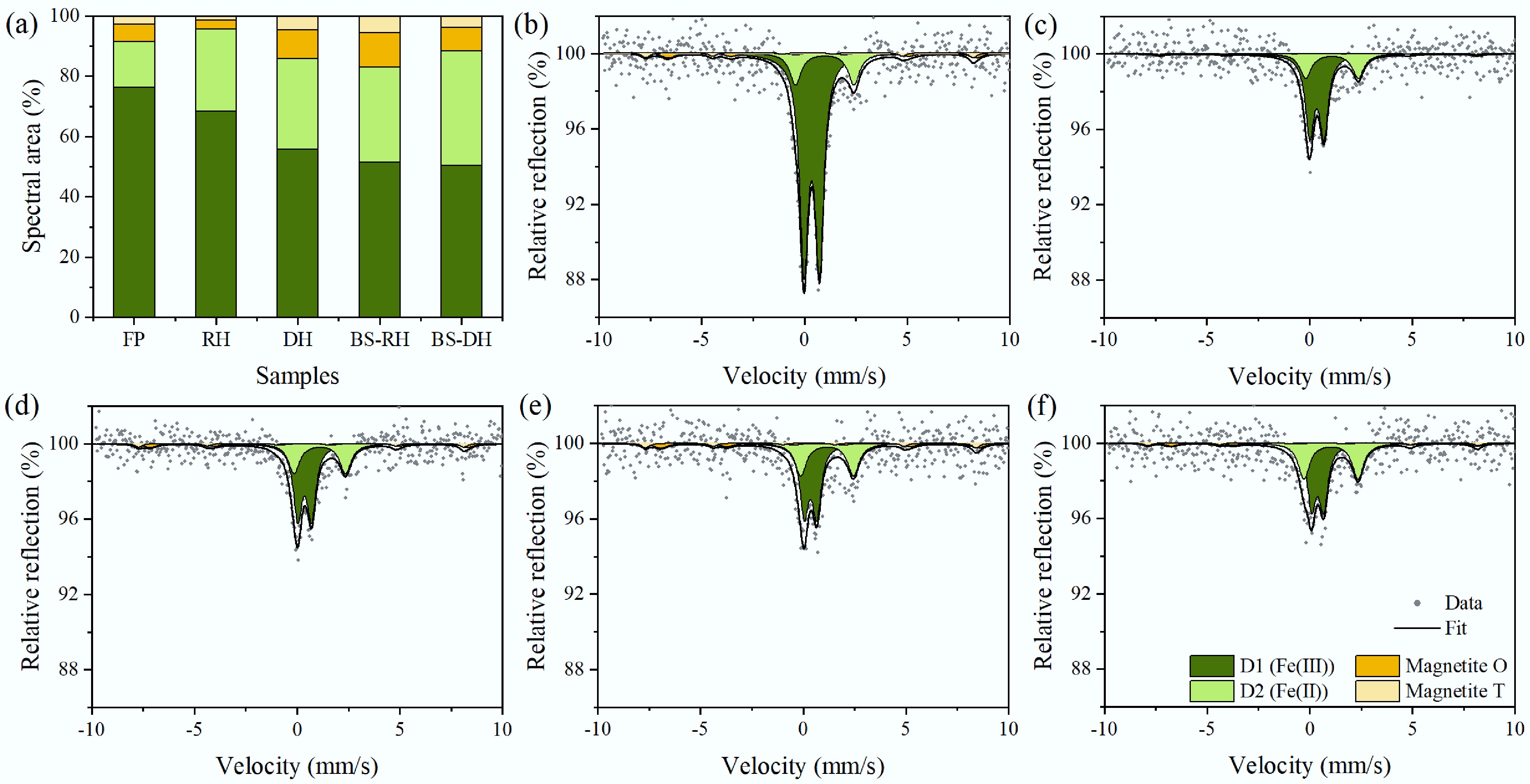

Mössbauer spectra revealed that the (super) paramagnetic Fe(III) fraction (doublet D1) was dominant in both the Fe plaques and rhizosphere, exceeding 76% and 68%, respectively (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S7). This fraction may include any combination of Fe (oxyhydr) oxides, such as ferrihydrite, lepidocrocite, low-crystalline fractions of hematite, as well as organic-matter-complexed or silicate-associated Fe(III)[42]. Sequential extraction results indicated that the Fe plaques primarily consisted of easily reducible Fe-oxides like ferrihydrite and goethite (Supplementary Fig. S8c). The solid-associated Fe(II) primarily consists of primary minerals, silicate-associated or adsorbed Fe(II) (doublet D2), which exceeded 30% in the detritusphere. D1 fraction was approximately 50% in the detritusphere, lower than that in the Fe plaques and rhizosphere. Additionally, the magnetite fraction increased from the rhizosphere to the detritusphere, surpassing 10%.

Figure 3.

(a) Fe phase fractions, and (b) corresponding Mössbauer spectra of Fe plaque (FP), (c) rhizosphere (RH), (d) detritusphere (DH), (e) bulk sediments during macrophytes growth (BS-RH), and (f) bulk sediments during macrophytes death (BS-DH).

Characterization of the microbial community structure and function

-

PCoA indicated significant differences in microbial communities among the rhizosphere, detritusphere, and bulk sediments (Fig. 4a). No significant differences were found between the bulk sediments of the rhizosphere and detritusphere (p > 0.05), so they were defined uniformly as bulk sediment for subsequent analyses. The α diversity indexes in the rhizosphere and detritusphere were greater than those in the bulk sediment (Fig. 4b). Proteobacteria were the dominant phylum, with relative abundances ranging from 37.92% to 46.51%, followed by Acidobacteria, Chloroflexi, and Bacteroidetes (Fig. 4c). LEfSe analysis revealed that Proteobacteria and Nitrospirae were significantly enriched in the rhizosphere, while Bacteroidetes, Spirochaetes, and Firmicutes were enriched in the detritusphere (Fig. 4d).

Figure 4.

Microbial diversity and community structures in the rhizosphere (RH), detritusphere (DH), and bulk sediment (BS). (a) Composition and structure differences of microbial communities using principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) based on the Bray-Curtis distance, with significant differences analyzed by permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA). (b) α-diversity, including the Chao1, Shannon, and Simpson indexes. (c) Relative abundance of bacterial communities at the phylum level. (d) Bacterial relationships among taxonomic units of microbiota, ranging from the phylum level down to the genus level. Significant differences at * p < 0.05, and ** p < 0.01.

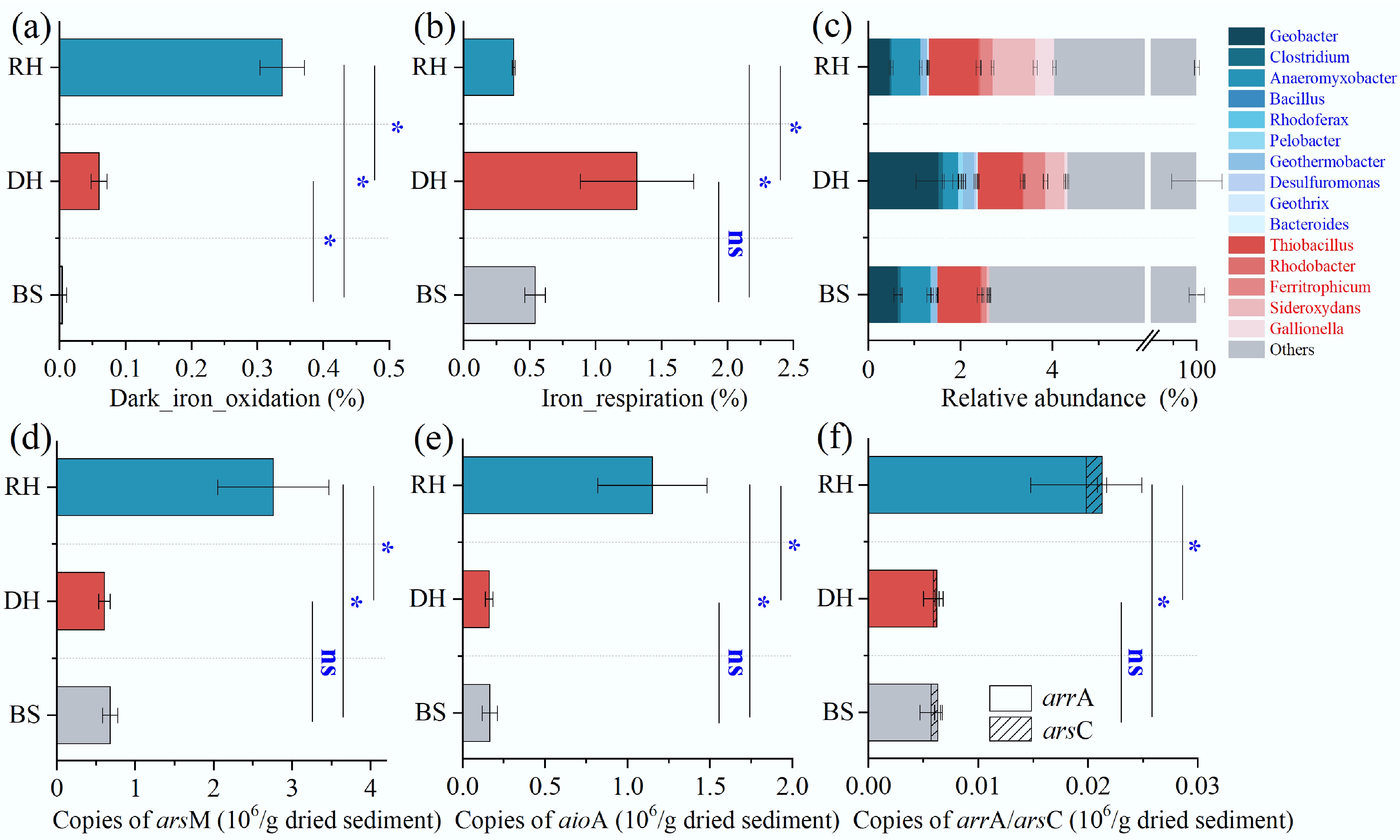

The bacterial functional profiles related to Fe cycling were characterized using the FAPROTAX tool (Fig. 5a, b). In the rhizosphere, microbes involved in Fe oxidation were more abundant than in the detritusphere and bulk sediment (p < 0.05). Thiobacillus and Sideroxydans were the predominant genera of Fe-oxidizing bacteria in the rhizosphere (Fig. 5c). Conversely, the iron_respiration function was stronger in the detritusphere than in the rhizosphere (p < 0.05), with Geobacter and Anaeromyxobacter being the most dominant Fe-reducing bacterial genus.

Figure 5.

Relative 16S rRNA (gene) abundance of Fe-cycling microbial communities and absolute quantification of As biotransformation genes in the rhizosphere (RH), detritusphere (DH), and bulk sediment (BS). (a) Dark_iron_oxidation function. (b) Iron_respiration function. (c) Relative abundance of typical Fe-reducing (bule text), and Fe-oxidizing (red text) bacteria. (d)–(f) Abundance of the arsM, aioA, arrA, and arsC, respectively. Significance levels at * p < 0.05; ns, not significant.

The abundances of arsM, aioA, arrA, and arsC were 2.76 ± 0.71, 1.15 ± 0.33, 0.02 ± 0.005, and 0.001 ± 0.0004 × 106 copies/g in the rhizosphere, respectively, all notably higher than in the detritusphere and bulk sediment (p < 0.05) (Fig. 5d–f). They were 4.54, 7.13, 3.36, and 4.17 times lower in the detritusphere than in the rhizosphere for arsM, aioA, arrA, and arsC, respectively. There were no significant differences in microbial As-cycling genes between the detritusphere and the bulk sediment (p > 0.05). Microbially driven As transformation processes underwent significant changes during the transition from rhizosphere to detritusphere.

-

The microcosm experiment demonstrated that macrophytes act as a crucial role in remediating sediment As pollution and controlling its release (Fig. 1). A significant negative correlation was observed between the release flux of soluble As and both the O2 penetration depth and Eh in sediments (p < 0.01) (Supplementary Fig. S4), indicating that ROL enhances the oxidative environment in sediments, which is a key factor in reducing As release. High-resolution chemical imaging further supported this finding, revealing lower labile As levels in the aerobic rhizosphere (Fig. 2). The results are consistent with recent studies emphasizing the significant influence of the rhizospheric effects of macrophytes on sediment As remediation[9].

In the aerobic rhizosphere, both the bacterial function involved in Fe oxidation and the abundance of Fe-oxidizing bacteria significantly increased (Fig. 5a, c), promoting Fe(II) oxidation and the development of Fe plaques (Supplementary Fig. S9). Iron plaques are a well-known strong adsorbent for both As(III) and As(V)[43]. Both significant positive correlations between labile Fe and As in both the sediment and rhizosphere (p < 0.01) (Supplementary Fig. S10a) suggested that sequestration of Fe plaques is a primary factor contributing to the decrease in As bioavailability. Mössbauer spectra and sequential extraction results showed that Fe plaques were predominantly composed of ferrihydrite and lepidocrocite (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. S8c), consistent with other studies of root plaques in rice observed by EXAFS (X-ray absorption fine structure) spectroscopy[11]. The poorly crystalline Fe minerals may be attributed to ROL-induced rapid redox turnover in the rhizosphere[9]. These Fe minerals are known to exhibit a strong affinity for As[44]. Approximately 20% of As was associated with these Fe minerals in Fe plaques (Supplementary Fig. S8d), which further supports the role of Fe plaque in immobilizing As. In addition, Fe plaques also have strong adsorption affinities for P[45], which contributes to the decrease in labile P in the rhizosphere (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S6).

Microorganisms are also critical for altering the As morphology, mobility, and toxicity[46]. Root growth significantly increased the abundance of genes linked to microbe-mediated As cycling in the rhizosphere (p < 0.05) (Fig. 5d−f). Microbially mediated As(III) methylation and oxidation can transform As(III), which has stronger mobility and toxicity, into organic As with lower toxicity, and As(V) with lower mobility, respectively[47]. Therefore, root-regulated improvement in microbial As(III) methylation and oxidation is another important reason for the reduction in sediment As immobilization. Genes involved in both respiratory As(V) reduction (arrA), and detoxifying As(V) reduction (arsC) showed a greater abundance in the rhizosphere compared to bulk sediments. In the rhizosphere, As(V) is the dominant As species, which provides sufficient reaction substrates for microbial reduction[46]. Although the rhizosphere showed a greater abundance of genes related to As reduction compared to bulk sediments, this was considerably lower than the abundance of As(III) methylation and oxidation genes.

Interestingly, labile Fe increased sharply at the boundary between the rhizosphere and bulk sediment (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S6). Root-induced formation of an aerobic–anaerobic interface may create a niche for Fe(III)-reducing bacteria, facilitating the reduction of Fe minerals[48,49]. This process might facilitate biogeochemical cycles of pollutants at the rhizosphere–sediment interface, which warrants further exploration. Labile Mn exhibited an opposite trend compared to labile Fe in the rhizosphere, showing significant negative correlations with labile P and As (Fig. 2, Supplementary Figs S6 and S10a). Carboxylates secreted from roots occur to mobilize the low-availability P, which might coincidentally enhance Mn availability in the rhizosphere[50]. Additionally, studies have indicated that Mn-oxides in the rhizosphere can chemically oxidate As(III) to As(V)[9,51]. The above processes not only promote rapid oxidation of As(III) and subsequent sorption of As(V) to Fe plaques, but also increase the Mn solubilization in the rhizosphere.

Increase in As mobility from the rhizosphere to the detritusphere

-

As the rhizosphere transitions to the detritusphere, changes take place such as to the microbial community structure[17,52]. However, it is still unknown whether the legacy effects of roots have implications for the mobility of As. We first found that root decomposition of macrophytes can enhance the release of As from sediments and raise the risk of aqueous As contamination. After the death of V. natans, the soluble As and labile As in sediments increased approximately 3.5-fold and 2-fold, respectively, compared to their levels during plant growth (Figs 1 and 2). An increase in the concentration gradient at the sediment-water surface further promoted the diffusive transport of As from sediment to overlying water (Supplementary Fig. S4).

The release of O2 from roots ceased after plants wither, coupled with the consumption of O2 by root degradation, transforming the aerobic rhizosphere into an anaerobic detritusphere (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S3). In O2-limited sediment, reductive dissolution of easily reducible Fe-oxides by Fe-reducing microorganisms is favored[53]. Previous studies have discovered that when Fe plaques are exposed to Fe(III)-reducing bacteria, approximately 30% of Fe(II) is remobilized, and more than 50% is converted by microbes to Fe(II) minerals[54]. This is consistent with our observations of Mössbauer spectra, which show a decrease in the (super)paramagnetic Fe(III) fraction, with an increase in the solid-associated Fe(II) fraction in the detritusphere compared to Fe plaque and rhizosphere (Fig. 3). The iron_respiration function significantly increased from the rhizosphere to the detritusphere, especially the Fe-reducing bacteria Geobacter (Figs. 4b, c), which plays a crucial role in reductive dissolution of Fe(III) minerals in Fe plaques.

After the death of V. natans, Fe(III) minerals formed during root growth may undergo rapid reduction; indeed, few root Fe deposits were collected from the detritusphere in this study (Fig. 2). This result suggests a significant reduction in the ability of the natural reactive barrier (Fe[III] minerals) to trap As in the detritusphere. In this study, there was 79.38% of total As lost from the Fe plaque (Supplementary Fig. S8b), which was comparable to the loss value measured in rice root Fe plaque i.e., 76.1% of total As loss within 27 d of degradation[20]. According to As fraction analysis, approximately 90% of Fe-bound As is lost during this process (Supplementary Fig. S8d). In the detritusphere, there was a significant positive correlation between labile As and Fe (p < 0.01) (Supplementary Fig. S10b), further demonstrating that reductive dissolution of Fe plaques is an important reason for the release of As from the sediment.

In the detritusphere, significant changes in As metabolism genes were observed when compared to the rhizosphere (p < 0.05) (Fig. 5d−f). Particularly, genes involved in As methylation, oxidation, and reduction exhibited a marked decline from the rhizosphere to the detritusphere, while they showed no significant differences between the detritusphere and bulk sediment. During macrophyte growth, roots create niches for microbial communities involved in As cycling, especially those microbes mediating As methylation and oxidation[9,55]. However, after the death of macrophytes, as the rhizosphere transitions to the detritusphere, the release of exudates and oxygen ceases, causing the collapse of specific rhizospheric microniches. This disrupts the microbial processes of As(III) oxidation and methylation driven by root growth. As a result, the decline in these microbe-driven processes contributes to an increase in As mobility and bioavailability in the sediment.

Implications on aqueous As contamination

-

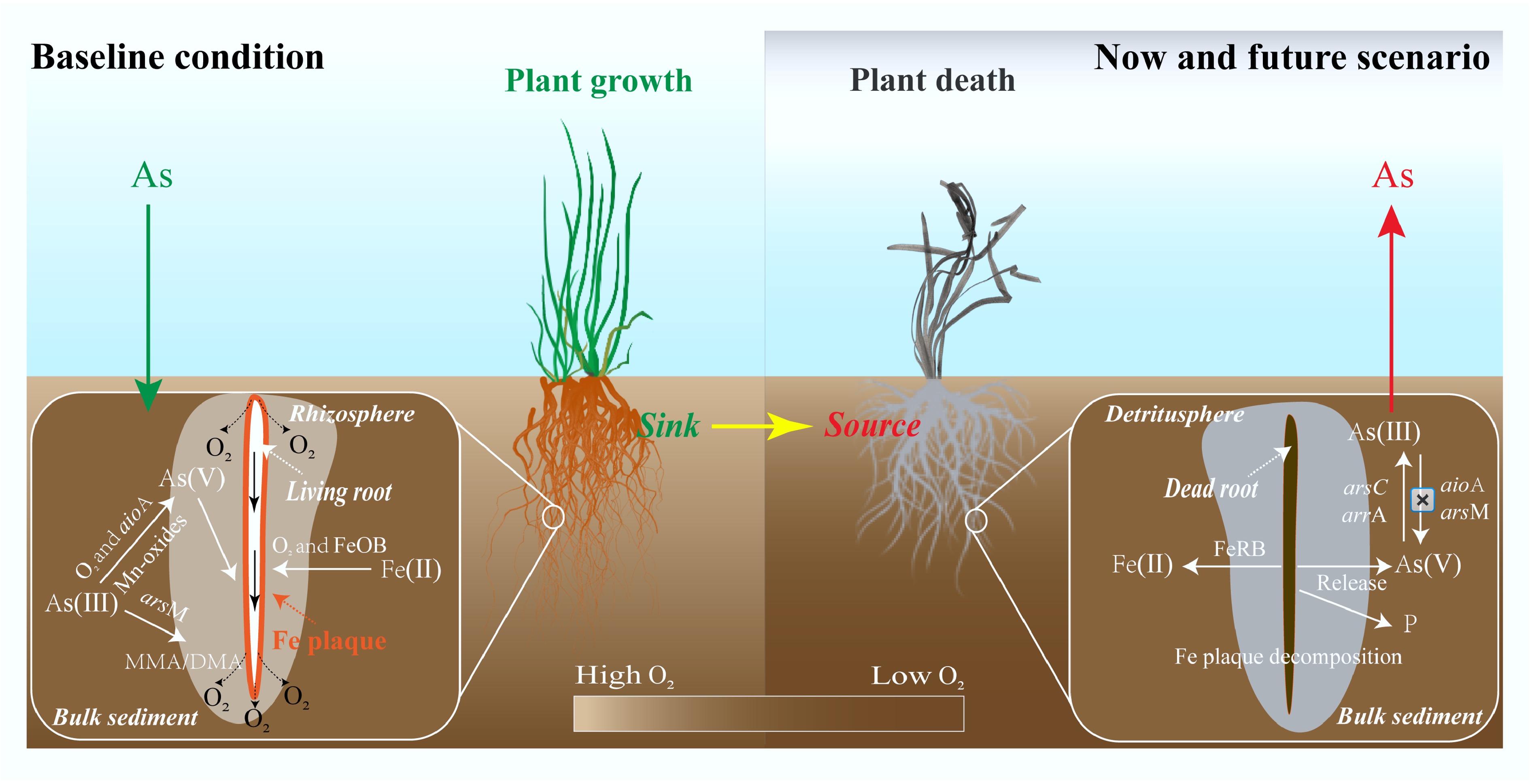

Two microcosm experiments were performed to reveal an overlooked pathway of aqueous As contamination, whereby sediment shifts from a sink to a source of As after macrophyte death. In the rhizosphere, the microbe-driven As(III) methylation and oxidation, along with Fe plaque sequestration, reduce the toxicity and mobility of As, resulting in a downward movement of soluble As from the overlying water into the sediment (Fig. 6). Recent studies suggest that submerged macrophytes have decreased by 30.4% in global lakes over the past two decades[16,56], and therefore the ability of the rhizosphere to alleviate sediment As pollution may vary in response to the transition from rhizosphere to detritusphere. After the death of macrophytes, the rhizosphere switches from controlling the mobility of As in sediments to functioning as the release hotspots of As driven by microbial decomposition of Fe plaques and reduced As biotransformation in the detritusphere (Fig. 6). Considering the widespread occurrence of macrophyte loss, it is possible that the 'rhizosphere traps' unexpectedly serve as a source of As, potentially exacerbating As pollution in waterbodies. Moreover, localized increases of labile P and S(-II) in the detritusphere may further threaten water quality.

Figure 6.

Conceptual diagram of As mobilization processes in the rhizosphere and detritusphere. Baseline conditions (left) are compared to now and future scenarios (right) of widespread loss of submerged macrophytes.

Our findings also offer valuable insights for water ecological restoration that not only focus on removing contaminations via macrophytes, but also consider the long-term impacts of their loss or seasonal death on sediment nature and water quality. Effective lake and waterbody management should integrate these potential processes into sediment and aquatic plant restoration strategies. By recognizing the dual role of 'rhizosphere traps' as both sinks and sources of contamination, we can develop effective measures ensuring the potential risks posed by macrophyte loss or seasonal death. For example, capping materials with oxidative functions can be applied to the sediment surface or mixed into the upper sediment layer[57,58], which specifically target As immobilization under the reducing conditions that develop in the detritusphere. This study offers new perspectives on how the growth and decomposition of macrophyte roots affect the mobilization of As in sediments. This knowledge can help us recognize and assess potential threats to water quality and ecosystems, particularly the possible release of pollutants enriched in the rhizosphere.

-

The findings of this study suggest that sediment shifts from a sink to a source of As after macrophyte death, as a result of differences in abiotic and biotic transformation of Fe and As between rhizosphere and detritusphere. During root growth, microbe-driven As(III) methylation and oxidation, as well as Fe plaque sequestration, increased the As immobilization in the rhizosphere. However, following macrophyte death, the combined effects of Fe plaque dissolution and impaired microbial-mediated As transformation significantly increased As mobilization, resulting in a net flux of As into the overlying water from sediments. It is important to note that future work should incorporate pH and organic matter dynamics, as root decomposition alters these factors, potentially affecting As mobility via competitive adsorption and complexation. This study offers new perspectives on how the growth and decomposition of macrophyte roots affect the mobilization of As in sediments, which can serve as a warning sign of aqueous As contamination, especially considering the widespread loss of submerged macrophytes globally.

We thank Zhilin Zhong for assistance with macrophyte cultivation and Mingyi Ren for assistance with instrumental methods of analysis.

-

It accompanies this article at: https://doi.org/10.48130/een-0025-0003.

-

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Cai Li, Xin Ma, Xue Jiang, and Youzi Gong. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Cai Li. Xiaolong Wang, Musong Chen, Qin Sun, and Shiming Ding discussed the results and commented on the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable requests.

-

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U2102210, 42407535, and 42277393), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (GZB20230782, 2024M763366), the Basic Research Program of Jiangsu (BK20241697), the Key Research and Development Program of Jiangxi Province (20223BBG74003), and the Long-term Program for Innovative Leading Talents of Jiangxi Province (jxsq2023101034).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

High-resolution sampling and analysis methods were used to study As mobilization.

Fe plaque sequestration and microbial transformations reduced As bioavailability.

Macrophyte loss transformed sediment from As sink into release hotspots.

Reductive dissolution of Fe-oxides and bioreduction enhanced As bioavailability.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Supplementary File 1 Supplementary materials and methods to this study.

- Supplementary Table S1 Water quality characteristics at the sampling sites in Lake Taihu.

- Supplementary Table S2 Soluble As concentration in the surface water, overlying water, and porewater, respectively, total As concentration in sediments at the sampling sites in Lake Taihu.

- Supplementary Table S3 Details of primer pairs of As-cycling genes.

- Supplementary Table S4 Details of extraction procedure for Fe speciation analysis.

- Supplementary Table S5 Details of extraction procedure for Shiowatana method.

- Supplementary Table S6 ROL rate in the rhizosphere of Vallisneria natans and other macrophytes.

- Supplementary Table S7 Mössbauer parameters of sediment samples collected from Fe plaque, rhizosphere and bulk sediment.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Microcosm experimental setup. (a) Microcosm experiment I containing Perspex tubes for monitoring the variations in porewater chemistry with root growth and root degradation. (b) Microcosm experiment II containing rhizoboxes for imaging the distribution of O2 and labile As.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 UV254 in the porewater during growth and death of submerged macrophytes.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 O2 dynamic in sediments from root growth to root decomposition.

- Supplementary Fig. S4 Soluble As concentrations in the overlying water (a) and porewater (b), the release fluxes of soluble As (c), as well as the correlation analysis between DO or Eh and the release flux of soluble As (d). Error bars represent standard deviations (±SD).

- Supplementary Fig. S5 Two-dimensional distribution of labile fluxes of As in the rhizosphere (a) and detritusphere (b), the white dotted lines represent the position of the roots.

- Supplementary Fig. S6 Soluble As concentrations in the overlying water (a) and porewater (b), the release fluxes of soluble As (c), as well as the correlation analysis between DO or Eh and the release flux of soluble As (d). Data were extracted from zone R1 and R2 in Fig. 2 Error bars represent standard deviations (±SD).

- Supplementary Fig. S7 Labile As fluxes in the rhizosphere of rhizosphere (a) and detritusphere (b), respectively. (Significance levels: ** p < 0.01).

- Supplementary Fig. S8 Total As (a) and total Fe (b), as well as Fe fractions (c) and As fractions (d) in sediment samples, bulk sediment 1 and 2 refer to the bulk sediment around rhizosphere and detritusphere. Error bars represent standard deviations (±SD).

- Supplementary Fig. S9 Image of root system of Vallisneria natans (a) and iron plaques (b).

- Supplementary Fig. S10 Correlation analysis of labile As, P, Fe, Mn, and S(-II) in the rhizosphere (a) and detritusphere (b), respectively. The data were extracted from R1 and R2 in Fig. 2.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Li C, Ma X, Jiang X, Gong Y, Wang X, et al. 2025. Unveiling an overlooked pathway of water arsenic contamination: microscale evidence of enhanced arsenic mobility from the rhizosphere to detritusphere of macrophytes. Energy & Environment Nexus 1: e008 doi: 10.48130/een-0025-0003

Unveiling an overlooked pathway of water arsenic contamination: microscale evidence of enhanced arsenic mobility from the rhizosphere to detritusphere of macrophytes

- Received: 10 June 2025

- Revised: 06 July 2025

- Accepted: 28 July 2025

- Published online: 16 October 2025

Abstract: The global decline of submerged macrophytes is accelerating, yet the processes involved in arsenic (As) mobilization in sediments remain poorly understood, particularly during the transition from the rhizosphere to the detritusphere. This study monitored the spatiotemporal variations of As, Iron (Fe), and associated microbial communities during root growth and degradation processes of macrophytes using high-resolution sampling and high-throughput sequencing techniques. Results showed that the As-depletion zones in the rhizosphere transformed into release hotspots of As after the death of macrophytes, resulting in an upward flux of 12.43 ng/cm2/d from sediments. This shift was driven by the significant changes in redox conditions and microbial functions related to Fe and As transformation. Transitioning from the aerobic rhizosphere to the anaerobic detritusphere, the relative abundance of Fe(III)-reducing bacteria increased by 81.23%, contributing to approximately 90% of Fe-bound As lost from Fe plaque. Furthermore, the significant decline in As(III) oxidase genes and methylation genes may have inhibited the oxidation and methylation of As(III), subsequently enhancing the availability and mobility of As in sediments. Thus, this transition fundamentally alters the fate of sediment from sinks to sources of As, highlighting unanticipated threats to water quality in light of widespread loss of macrophytes.

-

Key words:

- Arsenic /

- Submerged macrophyte /

- Sediment /

- Iron plaque /

- Microbial community