-

Since Leo Baekeland synthesized phenolic resin in 1907, plastics have become indispensable in modern society due to their low cost, durability, and wide range of applications[1]. By 2021, global annual plastic production had reached 390 million tonnes, with China accounting for 32% of the global share[2]. While plastics offer convenience, their persistence in the natural environment has also caused severe ecological problems[3,4]. A life-cycle assessment of 1,000 common plastic products (e.g., bags, meal boxes, cups) in the Chinese market reported carbon emissions ranging from 52.09 to 150.36 kg CO2 equivalent per kilogram[5]. Nicholson et al. further showed that supply chains linked to US plastic consumption generated approximately 104 million tonnes of CO2-equivalent greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from major commodity polymers (annual consumption ≥ 1 million tonnes)[6]. Projections indicate that without effective intervention, cumulative plastic waste in landfills and the natural environment could reach 12 billion tonnes by 2050[7]. Such waste not only occupies valuable land resources and hinders sustainable use but also migrates through ecosystems and accumulates in food chains, ultimately posing risks to human health. In response, governments and organizations worldwide are actively implementing multiple measures, including recycling, to mitigate the environmental impacts of plastics[8].

The main methods currently used to manage plastic waste are landfilling[9], mechanical recycling[10], and incineration. However, these conventional approaches face major challenges regarding both resource utilization efficiency and environmental sustainability.

Landfilling[11], currently the most widely used disposal method (≈40% of total), offers advantages such as low cost, operational simplicity, and large processing capacity. However, it requires large areas of land. More critically, additives in plastics (e.g., flame retardants) can leach into soil and groundwater under rainfall, leading to persistent pollution.

Mechanical recycling[12] separates mixed plastics into individual components using physical sorting methods (e.g., density, hardness, triboelectric separation) or spectroscopic techniques (e.g., near-infrared spectroscopy)[13]. The separated plastics are then cleaned, processed, and recycled for reuse. However, this approach faces several bottlenecks: low separation efficiency for complex mixtures and insufficient purity of the recycled pellets. These issues limit both the scope and the value of reuse. Moreover, repeated thermomechanical processing of thermoplastics inevitably degrades polymer chains, reducing mechanical properties (e.g., impact and tensile strength), and diminishing recycling value.

Incineration treats plastic waste through high-temperature oxidation, achieving volume reduction and potential energy recovery. Although about 34% of plastic waste is processed this way, the method has clear limitations[11]. Not all plastics are suitable for incineration, as combustion behavior depends heavily on structure and composition. For example, chlorine-containing plastics (e.g., PVC) can release highly toxic and carcinogenic compounds such as dioxins and furans, requiring complex and costly flue gas purification systems. In addition, incineration inevitably emits carbon dioxide (CO2), exacerbating the greenhouse effect[14]. Meanwhile, this method also significantly diminishes the value of waste plastic[15].

Given these limitations (low resource efficiency, secondary pollution, and carbon emissions), developing higher-value and more sustainable recycling solutions is urgent. Plastics can be converted into three categories of high-value products—gases, oils, and carbon materials—through various pathways. However, plastic-derived oils produce higher CO and NOx emissions than conventional fuels, worsening greenhouse effects[16]. Pyrolysis gases also contain high tar levels, requiring costly purification systems for industrial use[17]. Against this backdrop, efficient conversion of waste plastics into high-performance functional carbon materials has recently emerged as a highly promising research direction[18−20].

Functional carbon materials offer great potential in areas such as environmental remediation (e.g., CO2 adsorption), and energy storage (e.g., batteries and supercapacitors), owing to their unique electronic structures, tunable microstructures (e.g., pore size distribution, surface area, functional groups), and diverse dimensionalities (e.g., zero-dimensional carbon quantum dots, one-dimensional nanotubes, two-dimensional graphene, and three-dimensional porous carbon)[21]. Converting the abundant carbon in waste plastics into such materials can not only improve recycling efficiency and reduce dependence on fossil resources but also mitigate pollution from landfilling and incineration at the source. Importantly, this conversion route generally tolerates the complex composition of mixed plastics and can bypass labor-intensive sorting, making it broadly applicable[22].

Although several reviews have explored the conversion of waste plastics into functional carbon materials, most suffer from limited scope. Many focus on specific plastics (e.g., PET), specific carbon products (e.g., nanotubes, fullerenes, or activated carbon), or narrow applications. For example, Anusha et al.[23] summarized PET-derived nanotubes, fullerenes, and graphene nanosheets; Pereira et al.[24] examined plastic-derived activated carbon for wastewater treatment; Hou et al.[25] discussed value-added conversion and catalytic degradation but gave limited attention to preparation mechanisms, and Liu et al.[26] reviewed selected techniques, with emphasis on applications in electromagnetic shielding and microwave absorption.

Nevertheless, existing reviews still have notable gaps. First, coverage of carbon material types remains incomplete, with limited attention to products such as carbon spheres, nanosheets, and quantum dots derived from waste plastics. Second, emerging technologies—including laser direct writing (LDW) and 3D printing—have received little discussion. Finally, summaries of applications in environmental remediation and energy remain inadequate.

To address these gaps, this review provides a comprehensive discussion. First, it introduces the structures and physicochemical properties of the plastics with the highest global production volumes. Second, it summarizes recent advances in converting diverse waste plastics into various carbon materials, including nanotubes, graphene, porous carbon, spheres, nanosheets, quantum dots, and soft carbon. Third, it analyzes the principles and current status of different processes, with emphasis on emerging technologies such as LDW and 3D printing. Finally, it highlights key applications of waste-derived carbon materials in environmental protection and energy.

-

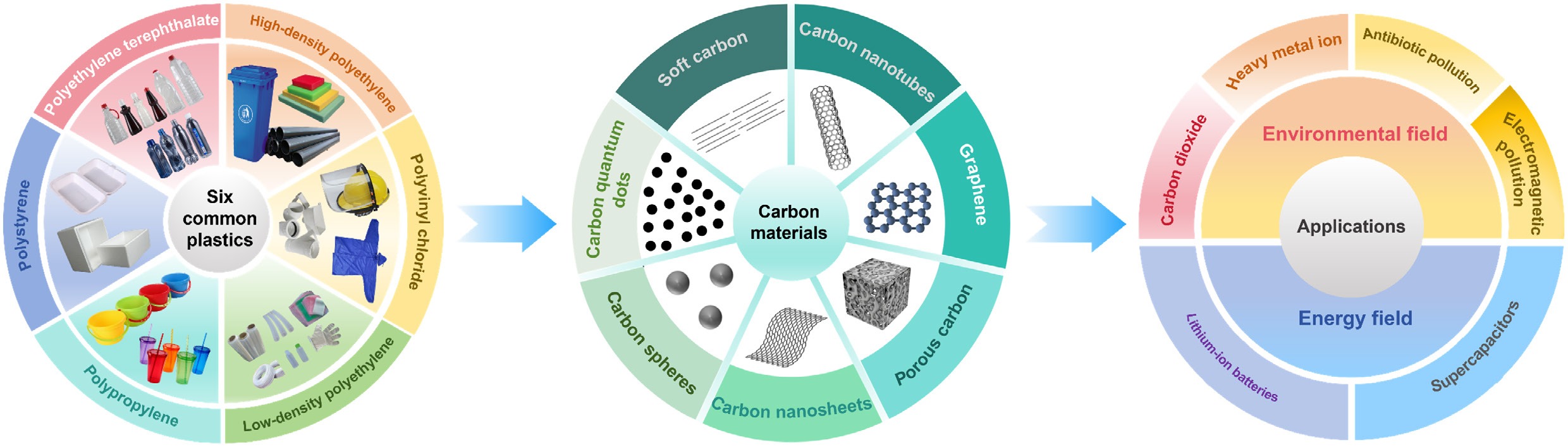

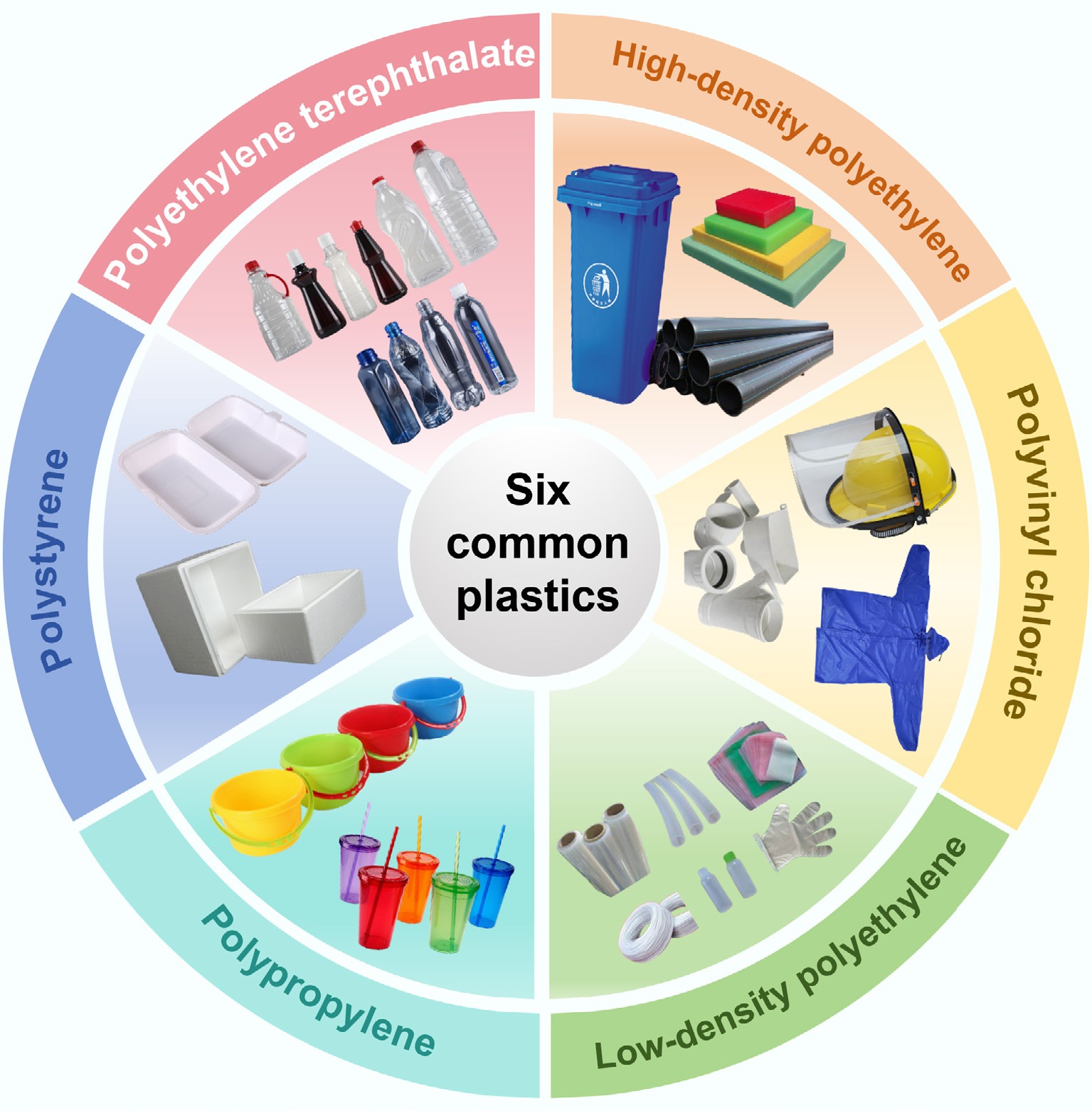

Although bio-based plastics are developing rapidly, global commercial plastic production still relies mainly on fossil fuels (coal, petroleum, and natural gas). To meet diverse application needs, thousands of plastics with different structures have been developed, making a comprehensive analysis impractical. According to Houssini et al.[11], the five leading plastics by global production share are polyethylene (PE, 26.3%), polypropylene (PP, 18.9%), polyvinyl chloride (PVC, 12.7%), polyethylene terephthalate (PET, 6.2%), and polystyrene (PS, 5.2%). Differences in their molecular structures (e.g., branching degree, functional groups, chlorine content) directly influence pyrolysis behavior (e.g., cracking temperature, product distribution) and the characteristics of the resulting carbon materials (Fig. 1). This section systematically analyzes their key physicochemical properties.

Figure 1.

Basic structure and product diagram of six common polymers (HDPE, LDPE, PP, PS, PVC, and PET).

Polyethylene (PE)

-

Polyethylene (PE) is a hydrocarbon polymer produced by polymerizing ethylene monomers. Based on chain branching, it is classified into high-density polyethylene (HDPE) and low-density polyethylene (LDPE). HDPE consists mainly of linear chains, with high crystallinity (80%–95%) and density (0.94–0.97 g/cm3). Its rigidity (elastic modulus 0.8–1.4 GPa) makes it suitable for load-bearing applications such as pipes and building materials. In contrast, LDPE has a highly branched structure, lower crystallinity (40%–60%), and density (0.91–0.94 g/cm3). Its excellent flexibility (elongation at break > 500%) makes it ideal for film packaging. HDPE requires higher activation energy for pyrolysis, with an initial cracking temperature of ~387 °C (main peak 430–480 °C), while LDPE cracks more readily at ~350 °C (main peak 400–450 °C) due to weaker bonds at branching sites. Both types generally require catalytic activation to improve carbon yield.

Polypropylene (PP)

-

Polypropylene (PP) is a thermoplastic polymer produced by polymerizing propylene monomers. The methyl side groups impart rigidity to its chains. Industrial production mainly yields isotactic PP (> 90%), which forms a highly regular helical structure[27].

PP has a density of 0.89–0.91 g/cm3 and a melting point of 160–170 °C, making it the lightest of the major plastics. Its high flexural modulus (1.5–2 GPa) and excellent resistance to acids, alkalis, and organic solvents support applications in automotive parts (bumpers, interiors), medical devices (syringes), food packaging (microwave containers), and synthetic fibers. Pyrolysis begins at ~327 °C (lower than PE), with cleavage at tertiary carbon sites producing methyl radicals. The products include propylene monomer (up to 40 wt%), methane, ethylene, and liquid paraffins. The residual char contains long-chain alkanes, making it a suitable hydrocarbon source for catalytic carbon nanotube production.

Polyvinyl chloride (PVC)

-

Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) is a thermoplastic produced by polymerizing vinyl chloride monomers[28]. The alternating chlorine atoms in its molecular chains confer flame retardancy, chemical resistance, and high mechanical strength. Owing to its high chlorine content (56.8 wt%), industrial products typically contain thermal stabilizers (e.g., calcium stearate) to inhibit dehydrochlorination. Rigid PVC has a density of 1.3–1.45 g/cm3, a heat deflection temperature of 70–85 °C, and an impact strength of 5–10 kJ/m2, and is mainly used in building materials such as pipes and window frames. Flexible PVC incorporates 30–40 wt% plasticizers (e.g., phthalates), reducing its density to 1.1–1.3 g/cm3 and enabling elongation at break of 200%–400%. It is widely applied in cable sheaths, hoses, and related products.

PVC pyrolysis typically proceeds in two stages. In the first stage (200–360 °C), dehydrochlorination occurs (yield > 50 wt%), leaving polyene chains. In the second stage (> 360 °C), hydrocarbon chain cracking generates benzene derivatives, which account for ~60% of the tar. The residual char contains chlorinated aromatic hydrocarbons—precursors of dioxins—necessitating treatment via chlorine fixation with Ca(OH)2 or catalytic hydrodechlorination.

Polyethylene terephthalate (PET)

-

Polyethylene terephthalate (PET), with the molecular formula (C10H8O4)n, is a high-molecular-weight semi-aromatic polyester synthesized by the polycondensation of terephthalic acid (TPA), or its dimethyl ester (DMT) with ethylene glycol (EG)[29]. It has a density of 1.38–1.41 g/cm3, a melting point of 240–260 °C, and is classified as a high-strength, high-modulus engineering plastic (tensile strength 55–75 MPa). Its excellent oxygen barrier property (oxygen transmission coefficient < 1 cm3/(m2·day)) makes it widely used in beverage bottles (~70% of production), textile fibers, and optical films.

During recycling, PET undergoes hydrolytic degradation, reducing its intrinsic viscosity from ~0.8 dL/g to ~0.6 dL/g. Thermal decomposition begins at ~425 °C and is dominated by ester bond cleavage. The main liquid products are terephthalic acid (30–45 wt%) and acetaldehyde (15–20 wt%), while gaseous products include CO and CO2. The char residue contains abundant oxygen-containing functional groups (15–25 at% O) and can be directly converted into surface-active porous carbon.

Polystyrene (PS)

-

Polystyrene (PS) is a transparent, rigid thermoplastic produced by free-radical or ionic polymerization of styrene monomers. Commercial PS is classified into general-purpose (GPPS, transparent, and rigid), and expanded (EPS) grades, the latter incorporating a pentane blowing agent to create a closed-cell structure. GPPS has a density of 1.04–1.07 g/cm3, a glass transition temperature of ~100 °C, and optical transparency up to 90%. It is brittle (elongation at break < 3%) but exhibits excellent electrical insulation properties (dielectric strength ~20 kV/mm). EPS has a very low density (0.01–0.04 g/cm3) and outstanding thermal insulation performance (thermal conductivity < 0.03 W/m·K), making it widely used in building insulation panels and cushioning packaging.

Pyrolysis begins at ~364 °C, where the conjugated benzene rings delay chain scission. The main product is styrene monomer (yield > 50 wt%), accompanied by benzene, toluene, and ethylbenzene (20–30 wt% combined). The carbon residue contains fused-ring aromatic hydrocarbons (e.g., acenaphthene, anthracene), with an aromatic carbon content exceeding 90%, providing inherent advantages for conversion into graphene or porous carbon.

-

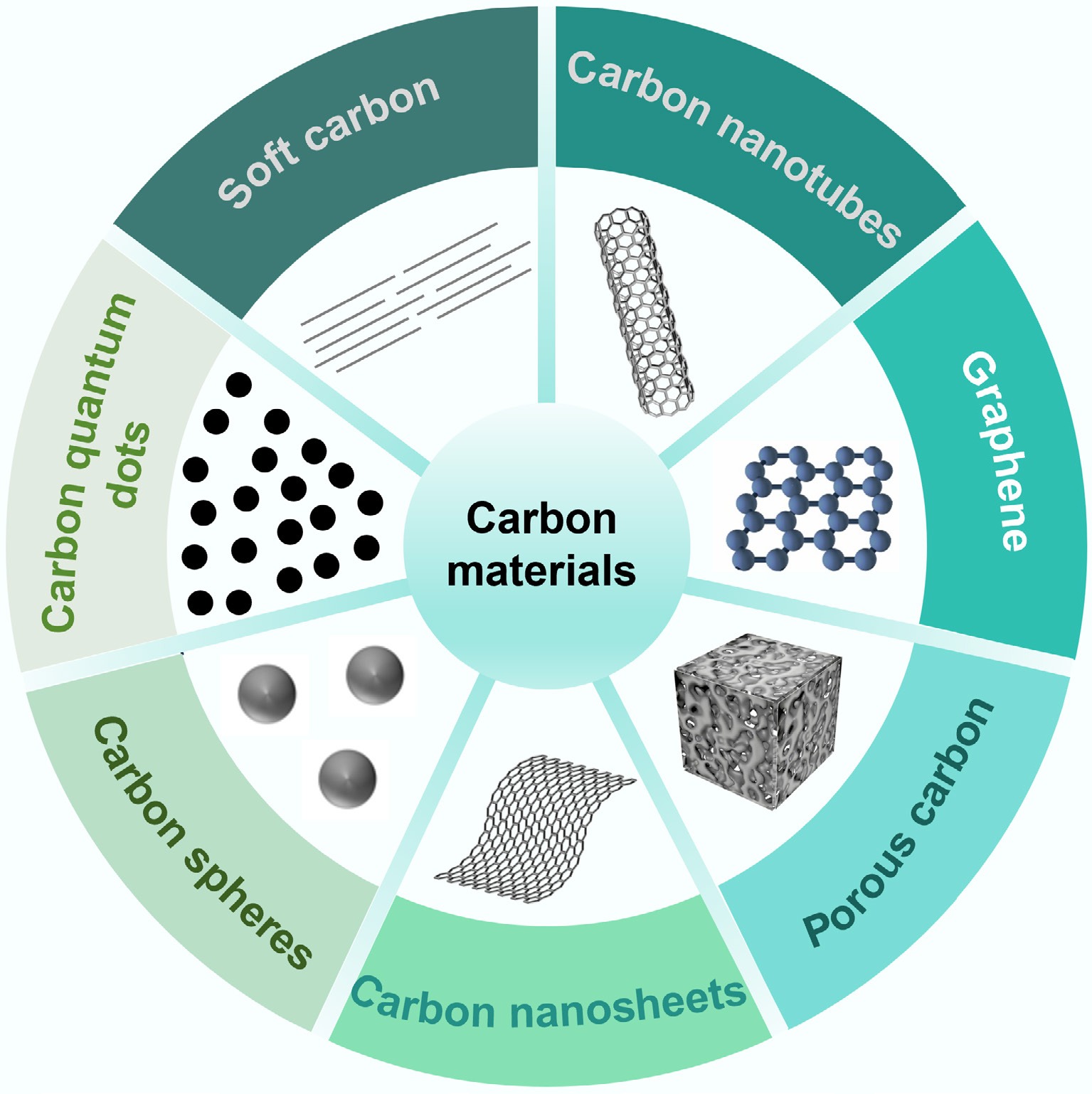

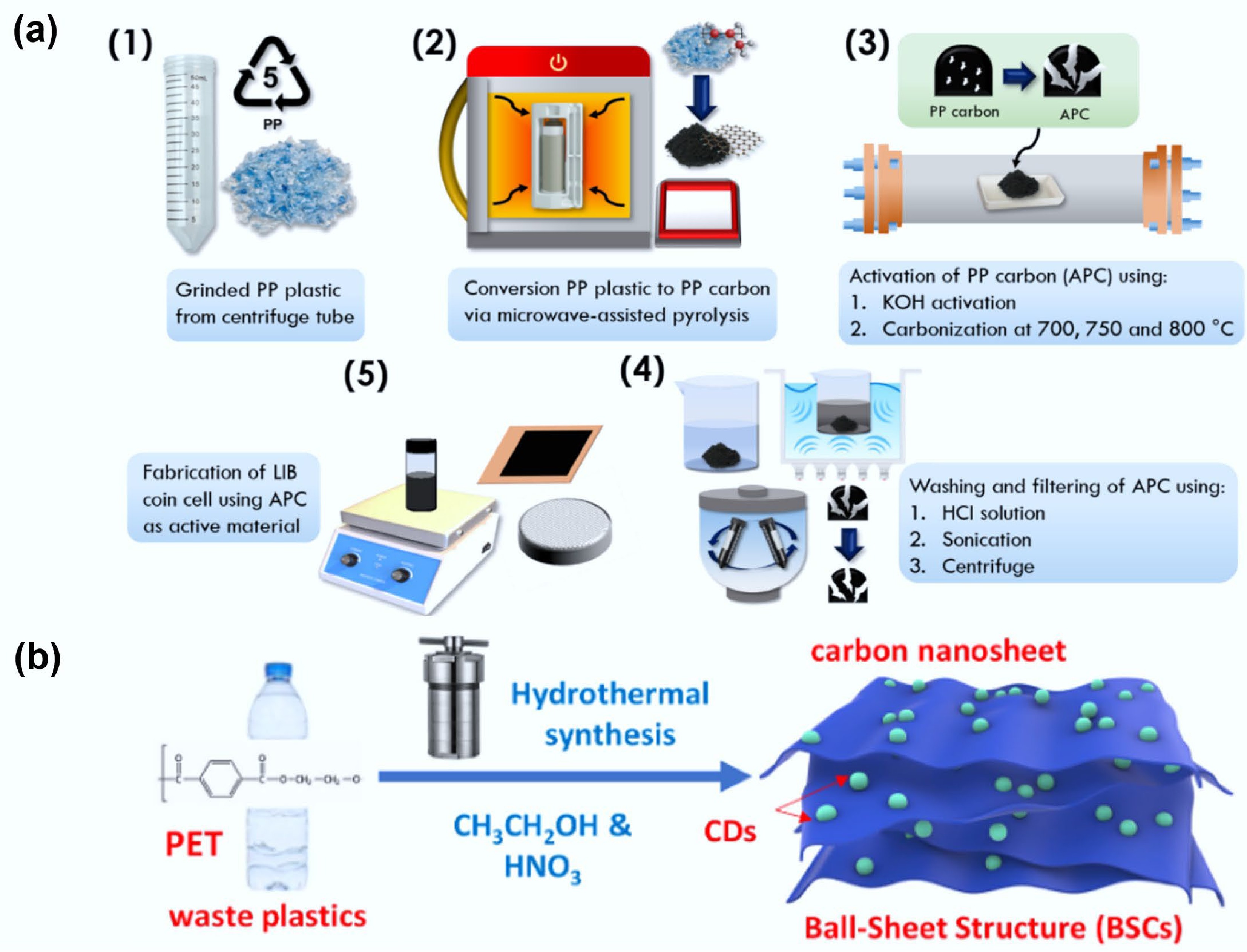

To realize high-value recycling of waste plastics, researchers have developed various conversion pathways that reconfigure them into functional carbon materials. The diversity of the resulting products arises mainly from differences in synthesis methods, and process parameters (e.g., temperature, catalysts, activating agents), which strongly influence dimensionality, pore topology, and surface chemistry. The mainstream products can be grouped into seven categories: carbon nanotubes (CNTs), graphene, porous carbon, carbon spheres, carbon nanosheets, carbon quantum dots, and soft carbon (Fig. 2). This section systematically analyzes the intrinsic structures and functional properties of these materials, providing a theoretical basis for later discussion of their synthesis processes and application scenarios. The characteristics of selected functional carbon materials derived from different waste plastics are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Seven types of functional carbon materials derived from the carbonization of plastic waste.

Table 1. Comparative characteristics of waste plastics as precursors for different functional carbon materials

Carbon functional materials Types of plastics Method Specific surface area (m2/g) Characteristic

parameterID/IG Carbon

yield (%)Application Ref. Carbon

nanotubesMixed plastic Catalytic pyrolysis − − 0.30−0.34 − − [30] PP Catalytic pyrolysis 1.37–46.51 10–30 nm

(outside diameter)0.45−0.81 93 − [31] HDPE/LDPE/PS Catalytic pyrolysis − 16–19 nm (outside diameter) 0.9−1.5 37 ± 7 − [32] Graphene PET Chemical vapor deposition − − 0.38 (IG/I2D) − − [33] Porous

carbonMixed plastic Direct pyrolysis 596.01–2,328.2 − 0.806−0.942 − Lithium selenium batteries and zinc ion hybrid supercapacitors [34] PS Catalytic pyrolysis 1,033.58 − 0.95−1.12 − Palm oil hydroprocessing [35] HDPE Self-pressurized pyrolysis 2,785–2,913 − 0.79−0.94 67.49 Supercapacitor [36] Carbon

spheresPP One-pot synthesis − 1–8 μm (diameter) 0.57 42.4 Synthesis of nanocrystalline copper oxide [37] HDPE − 0.6 35.6 PVC − 0.55 33.6 Carbon nanosheets PP One-pot synthesis 3,200 4–4.5 nm (thickness) 0.53–0.80 62.8 Supercapacitor [38] PE Direct pyrolysis 1,043.4 − 0.92 4.2 Organic pollutant degradation [39] PP 765.1 0.89 0.9 PVC 703.7 1.03 28.6 Carbon

quantum

dotsPE One-pot synthesis − 5–30 nm (size) − 64 Determination of biocompatibility activity [40] PE/PP One-pot synthesis − − − − Determination of the concentrations of three iron ions in aqueous solution [41] Soft carbon PE One-pot synthesis − − − − Lithium ion battery [42] Carbon nanotubes (CNTs)

-

Carbon nanotubes (CNTs), with their unique one-dimensional tubular structure, exhibit ultrahigh electrical conductivity (> 106 S/m), excellent thermal conductivity (≈3,000 W/m/K), and outstanding mechanical strength (50–200 GPa). These properties make CNTs a primary target for the high-value conversion of waste plastics[43].

CNTs consist of single or multiple graphene sheets rolled into hollow tubes, with carbon atoms bonded through sp2 hybridization in a hexagonal lattice. Depending on the number of walls, they are classified as single-walled CNTs (SWCNTs, diameter 0.4–2 nm) or multi-walled CNTs (MWCNTs, diameter 2–100 nm). Their lengths can reach the millimeter scale, with aspect ratios exceeding 1,000.

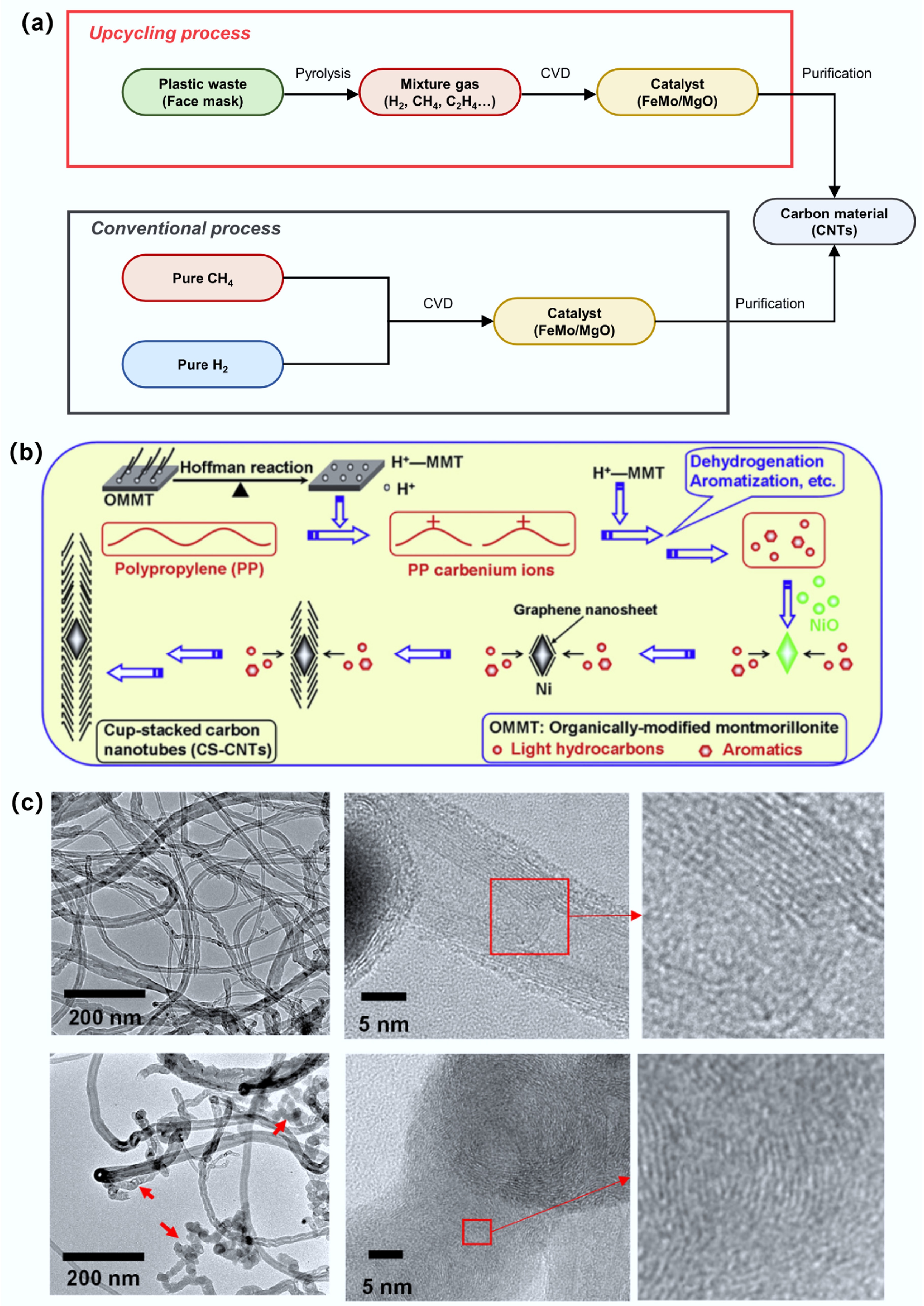

Mainstream preparation techniques include arc discharge[44], plasma methods[45], and chemical vapor deposition (CVD)[30]. Among these, CVD is the preferred industrial method because of its simplicity, high yield (> 90%), and low cost. Kim et al.[30] applied a coupled pyrolysis–CVD process and found that CNTs derived from waste mask plastics had comparable average diameters and graphitization degrees to those synthesized from methane. Moreover, they exhibited fewer structural defects and a higher proportion of few-walled CNTs, highlighting the structural advantages of plastic-derived CNTs (Fig. 3a).

Figure 3.

(a) Comparison of progress between upcycling and conventional process for CNTs synthesis. Reproduced with permission[30] (Copyright 2024 Elsevier). (b) Schematic diagram of high-quality cup stacked carbon nanotubes (CS-CNTs) synthesized using polypropylene as raw material and organic modified montmorillonite (OMMT)/NiO as catalyst. Reproduced with permission[46] (Copyright 2013 Elsevier). (c) TEM images of MWCNTs from polyolefin alone and MWCNTs from polyolefin and sludge (9.1 wt%). Reproduced with permission[32] (Copyright 2024 Elsevier).

Transition metal catalysts (Fe/Ni/Co) significantly enhance CNT quality by regulating carbon dissolution-precipitation kinetics. For instance, Wang et al.[31] reported that using polypropylene as the carbon source, and a Ni/cordierite catalyst in a fixed-bed reactor produced fibrous carbon with a yield of 93 wt%. The optimal morphology was obtained at 1.0 MPa; at higher pressures (> 1.0 MPa), tube diameters increased (30–50 nm) and the proportion of CNTs decreased markedly.

Catalyst design is critical for morphology-specific control. Gong et al.[46] developed an organically modified montmorillonite (OMMT)/NiO composite catalyst (Fig. 3b). The protonic acid sites on the OMMT surface promoted the dehydrogenation and aromatization of polypropylene, enabling efficient conversion into cup-stacked CNTs (CS-CNTs). Song et al.[47] used poly(ionic liquid) (PIL-I) to regulate the formation of a Ni/CS-CNT composite, achieving an evaporation rate of 1.67 kg/m2/h and a solar-to-vapor conversion efficiency of 94.9% in photothermal applications. Liu et al.[48] employed acid-washed stainless-steel mesh—where removal of the surface chromium oxide layer exposed Fe/Ni active sites—to catalyze waste plastic pyrolysis. This achieved 86% carbon recovery and 70% hydrogen recovery, confirming that the catalyst efficiently converted aromatics into MWCNTs via a vapor–solid mechanism.

Feedstock composition also strongly influences product characteristics. Chen et al.[49] used a mixed carbon source of polyurethane (PU) and ethylene–vinyl acetate (EVA), finding that PU favored the formation of small-diameter few-walled nanotubes (FWNTs), whereas EVA tended to produce MWCNTs. Tube diameters could be tuned by adjusting the blend ratio. Conversely, Veksha et al.[32] observed that biomass impurities (e.g., 9.1 wt% coconut coir) significantly inhibited polyolefin conversion, reducing MWCNT yields from 33 ± 7% in pure systems to 16%–20% because of catalyst deactivation (Co–Mo system) by impurities (Fig. 3c). However, the intrinsic parameters of the successfully formed CNTs remained largely unchanged.

Graphene

-

Graphene is a two-dimensional honeycomb crystal composed of a single layer of carbon atoms bonded via sp2 hybridization. Its unique structure gives rise to exceptional properties: a Young's modulus of ≈1 TPa (approaching the theoretical limit), an intrinsic tensile strength of 130 GPa (about 100 times that of steel), a current-carrying capacity of 108 A/cm2 (roughly 100 times that of copper), and a room-temperature thermal conductivity of 3,000–5,000 W/m/K (surpassing that of diamond).

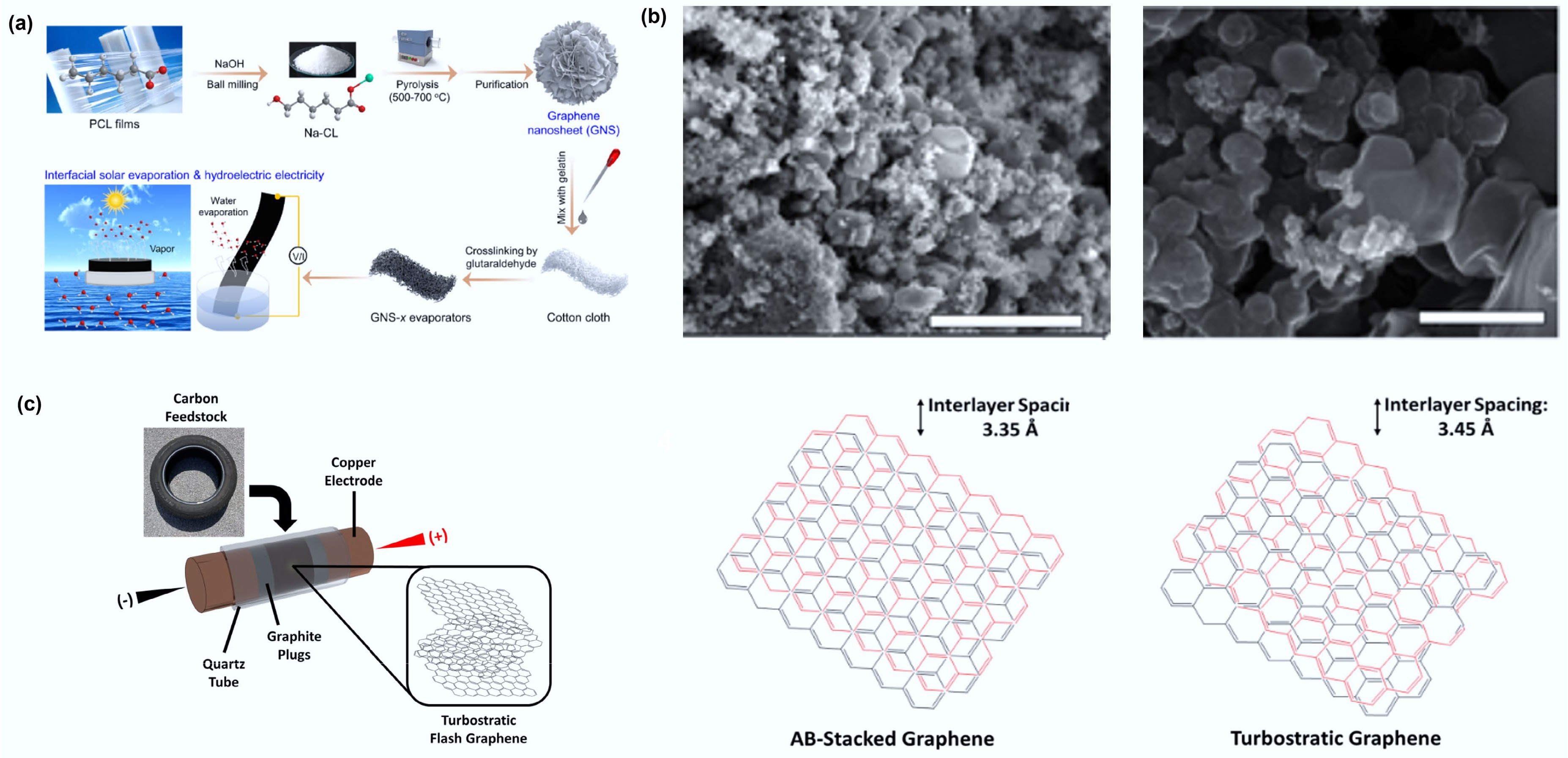

Based on the number of layers, graphene can be classified as monolayer or few-layer, although preparing monolayer graphene remains a significant challenge. In a notable advance, You et al. employed a green chemical vapor deposition (CVD) method to convert PET plastic into monolayer graphene, providing a novel approach for plastic valorization[33]. Meanwhile, the Hu team developed a salt-assisted carbonization process that successfully transformed waste poly(ε-caprolactone) into few-layer wrinkled graphene (7–8 layers) (Fig. 4a) . The material's curved-edge structure and abundant oxygen-containing functional groups further enhanced its surface activity[50].

Figure 4.

(a) Design for the preparation of GNS-x evaporators from waste plastic for interfacial solar-driven evaporation and hydrovoltaic power generation. Reproduced with permission[50] (Copyright 2024 Elsevier). (b) SEM images of wrinkled graphene (left) and tFG crystals (right). The scale bars on the left and right are 3 μm and 500 nm, respectively. Reproduced with permission[51] (Copyright 2021 Elsevier). (c) Schematic depicting the sample setup of the FJH system for conversion of rubber waste into tFG. Reproduced with permission[52] (Copyright 2021 Elsevier).

Flash Joule heating (FJH) technology has attracted significant research attention due to its high efficiency and energy-saving characteristics. The Pacchioni team converted mixed plastic waste into flash graphene (FG) via rapid discharge (> 106 K/s)[53]. This FG exhibited superior dispersibility compared to commercial graphene and was used as an additive in polyurethane foam for automotive sound management. Experimental results demonstrated that incorporating FG significantly enhanced both the mechanical properties and sound insulation performance of the polyurethane foam.

Wyss et al. obtained high-purity turbostratic graphene (tFG) through FJH (Fig. 4b)[51]. When incorporated into a polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) matrix at concentrations of 0.1–1 wt%, the fracture strain of the composite material increased markedly, while its water adsorption capacity decreased significantly. The Luong team further confirmed that FJH-produced FG possesses the lowest defect concentration, with its turbostratic stacking structure enabling excellent exfoliation properties[54]. Research by Advincula et al. (Fig. 4c) also validated the versatility of the FJH technique[52,55]. By optimizing the FJH process, researchers obtained turbostratic graphene with larger interlayer spacing than traditionally AB-stacked graphene. This enhanced spacing effectively preserves the ideal physicochemical properties of monolayer graphene.

Alternative processes can also effectively produce graphene materials. Gu et al. employed a mechanochemical exfoliation-microwave graphitization synergistic strategy to convert PE plastic bags into few-layer graphene, achieving a specific surface area of 1,521.3 m2/g and an electrical conductivity of 4,618 S/m (measured by the four-point probe method), making it suitable for high-power supercapacitors[56]. The Cui team developed a solid-state CVD process to convert everyday plastic waste into graphene foil (GF), which exhibited high electrical conductivity (3,824 S/cm) and good flexibility, demonstrating potential in flexible electronics[57]. These advancements collectively demonstrate the technical feasibility of converting waste plastics into graphene. Among these, FJH shows the greatest potential for scale-up due to its millisecond reaction time and low energy consumption (< 0.1 kWh/kg).

Alternative methods can also efficiently produce graphene materials. Gu et al. employed a synergistic mechanochemical exfoliation–microwave graphitization strategy to convert PE plastic bags into few-layer graphene, achieving a specific surface area of 1,521.3 m2/g and an electrical conductivity of 4,618 S/m (measured by the four-point probe method), making it suitable for high-power supercapacitors[56]. The Cui team developed a solid-state CVD process to convert everyday plastic waste into graphene foil (GF), which exhibited high electrical conductivity (3,824 S/cm) and good flexibility, demonstrating potential for flexible electronics[57]. Collectively, these advancements demonstrate the technical feasibility of converting waste plastics into graphene. Among these approaches, FJH shows the greatest potential for scale-up due to its millisecond reaction time and low energy consumption (< 0.1 kWh/kg).

Porous carbon

-

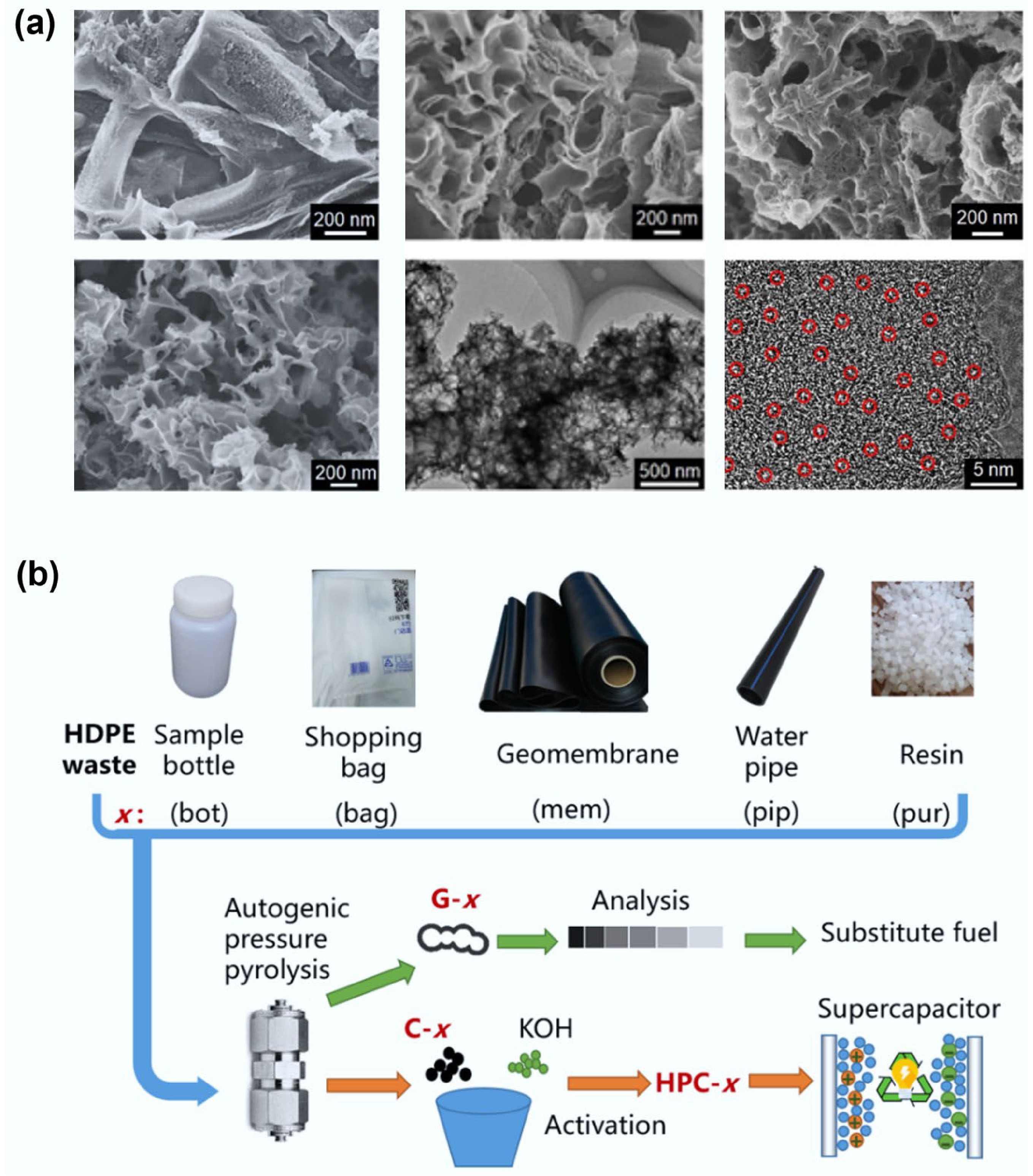

Porous carbon materials have attracted significant research attention in the field of functional materials due to their tunable pore structures and rich surface chemistry (Fig. 5a)[58]. Their physical characteristics include a hierarchical pore system—comprising micropores, mesopores, and macropores—which endows them with a high specific surface area (up to 3,000–5,000 m2/g) and well-developed pore volume (up to 5 cm3/g). These features directly determine their outstanding adsorption capacity and mass transfer efficiency. In addition, the sp2/sp3 hybridized structures within the carbon skeleton provide adjustable electrical conductivity (ranging from 10 to 103 S/m) and good mechanical stability[15].

Figure 5.

(a) Researchers adjusted the ratio of ZnO/PET in the raw materials to prepare porous carbon materials with different pore structures. Reproduced with permission[58] (Copyright 2022 John Wiley and Sons). (b) Schematic diagram of preparing porous carbon from mixed plastics and using it for carbon dioxide capture. Reproduced with permission[36] (Copyright 2023 Elsevier).

KOH chemical activation is an effective means to prepare high-performance porous carbon. Hoseini and colleagues used mixed plastic waste as the feedstock[34]. After pyrolysis at 400 °C under a nitrogen atmosphere, they activated the resulting char with KOH at 600 °C to obtain porous carbon (PWC600). PWC600 was subsequently employed as a cathode material in lithium-selenium (Li-Se) batteries. It maintained a stable specific capacity of 655.2 mAh/g after 150 cycles at a 0.1 C rate, reaching 97% of the theoretical capacity of selenium. This performance was attributed to the material's low charge-transfer impedance and the effective confinement of selenium by the highly microporous structure of PWC600.

In a similar manner, Ligero and colleagues developed a process for the targeted activation of char derived from the pyrolysis of waste plastics[59]. The research revealed significant differences in material structural properties between physical activation (N2/CO2 atmosphere) and chemical activation (KOH/NaOH). The results of the study demonstrated that chemical activation at 760 °C (for KOH) or 800 °C (for NaOH) resulted in the formation of a well-developed microporous structure (specific surface area up to 487 m2/g), whose performance significantly surpassed that of products from physical activation at a peak temperature of 720 °C. Further investigation revealed that when the char-to-KOH mass ratio was optimized at 2:1, the activated carbon demonstrated a CO2 adsorption capacity of 62.0 mg/g under low-temperature conditions (15 °C).

Kaewtrakulchai et al.[35] employed a co-hydrothermal carbonization-activation synergistic strategy to treat polystyrene packaging waste, thus making an innovative contribution to the field. The material was subjected to a reaction with corn stover at 350 °C for a duration of 5 h, utilizing a blend ratio of 30% polystyrene. This process resulted in the conversion of the material into a nanoporous carbon support (PMPC) with a specific surface area of 1,033.58 m2/g and a pore volume of 0.45 cm3/g. The polystyrene contributed an aromatic hydrocarbon skeleton while the cellulose carbon, derived from the corn stover, constructed a three-dimensional network support. Following the loading of nickel phosphide (NiP-PMPC), it showed excellent green diesel selectivity in the context of palm oil hydroprocessing.

Addressing the issue of real-world plastic waste (PWs) containing additives, Zhou and colleagues utilized actual high-density polyethylene (HDPE) plastic waste containing calcium carbonate (CaCO3), and carbon black additives[36]. The conversion of PWs into methane and hierarchical porous carbon (HPC) material was achieved through a self-pressurized pyrolysis process coupled with KOH activation. The resultant methane exhibited a purity level of > 93%, while the HPC material demonstrated a high specific surface area (2,785 to 2,913 m2/g) (Fig. 5b). The resulting HPC exhibited remarkable electrochemical performance when employed in supercapacitors, exhibiting a specific capacitance of 301 F/g at a current density of 1 A/g, commendable rate capability (89.1% capacitance retention at 20 A/g), and exceptional cycling stability (82% capacity retention after 5,000 charge-discharge cycles). The study found that although additives had minimal impact on the product distribution and methane content, they significantly altered the structural morphology and performance characteristics of the HPC. The HPC prepared from the additive-containing system showed an increased proportion of mesopores and macropores and richer surface functional groups, but a reduced degree of graphitization. These structural changes consequently affected the capacitive performance of the HPC.

Carbon spheres

-

Carbon spheres have emerged as a focal point in functional materials due to their perfect geometric symmetry and controllable hierarchical structure. Their physical characteristics include a strictly spherical morphology (diameter 0.1–100 μm) and designable surface chemistry, imparting ultrahigh fluidity resulting from an ultra-low angle of repose (< 15°) and tunable wettability (contact angle 0–170°). Furthermore, precise control over the core-shell structure (solid, hollow, or porous cavity) provides unique mechanical properties (compressive strength > 1.5 GPa) and optimized mass transfer pathways (radial diffusion efficiency enhanced 3–5 times compared to bulk carbon)[60].

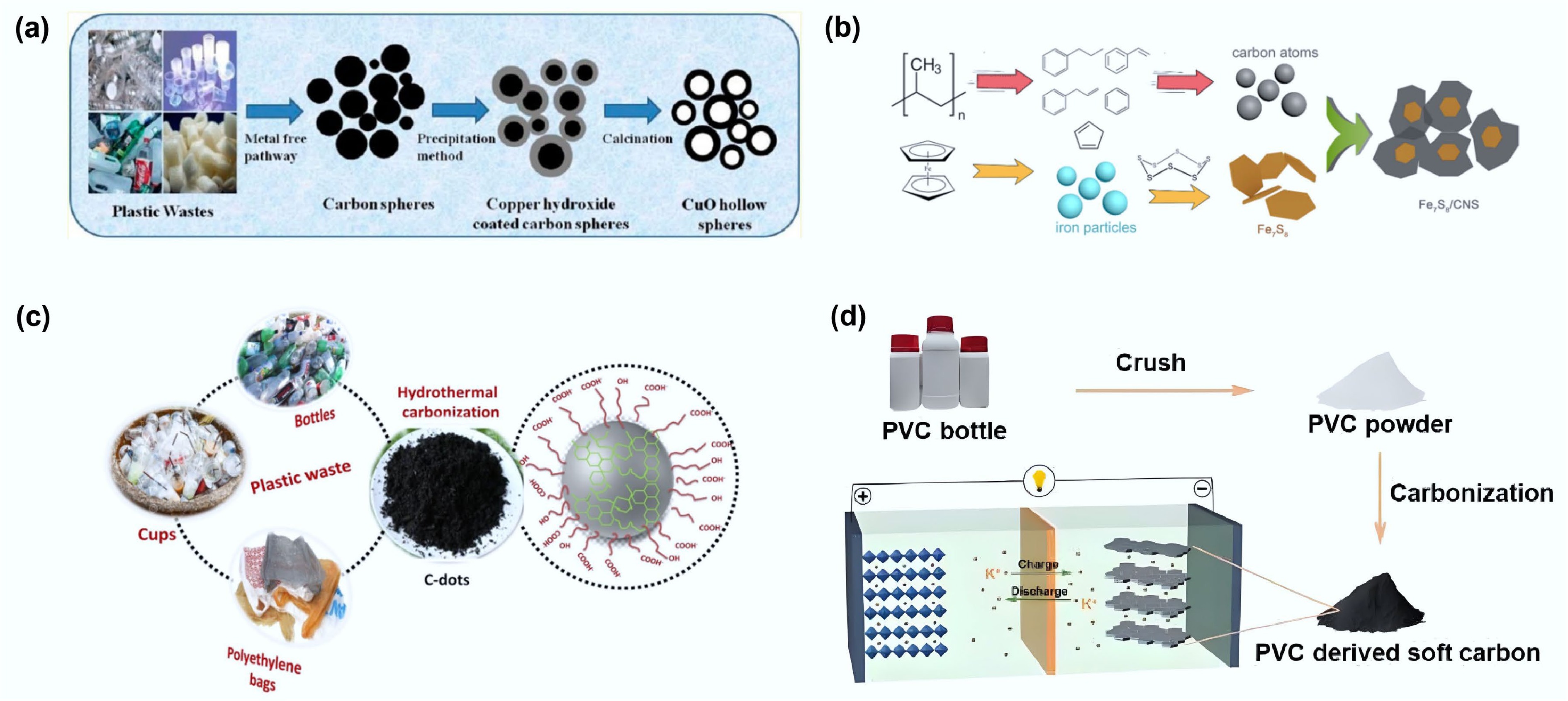

Sawant and colleagues utilized waste plastic as the carbon source to synthesize carbon microspheres with diameters of 1–8 μm via a one-step method under self-generated pressure at 700 °C (Fig. 6a)[37]. The resulting spheres exhibited a high degree of hydrophobicity, being free from metal impurities, and requiring no purification. The results demonstrated that only polyethylene (LDPE/HDPE), polypropylene (PP), and polycarbonate (PC) could be completely converted (100%) into carbon microspheres within this diameter range, while other plastics concurrently generated amorphous carbon.

Figure 6.

(a) Schematic diagram of preparing carbon spheres from waste plastics and using them as templates to produce hollow copper oxide spheres. Reproduced with permission[37] (Copyright 2013 American Chemical Society). (b) Schematic drawing of the formation process of Fe7S8/CNS composite from waste PP. Reproduced with permission[38] (Copyright 2021 Elsevier). (c) Schematic illustration showing the formation of C-dots from different types of plastic waste. Reproduced with permission[40] (Copyright 2021 Elsevier). (d) PVC-derived soft carbon anodes for potassium-ion batteries. Reproduced with permission[61] (Copyright 2023 John Wiley and Sons).

In addition to conventional synthesis methods, novel techniques are also applied. Fathi and colleagues efficiently converted polypropylene (PP) and carbon dioxide (CO2) into syngas and structurally ordered nanocarbon particles using a DC steam plasma torch[62]. The measured wall temperature within the reactor ranged from 1,150 to 1,350 °C, while the core steam plasma temperature reached approximately 10,000 °C. By introducing the gasifying agent (CO2) at sub-stoichiometric or above-stoichiometric ratios, a CO2 conversion rate of 98.5% was achieved. The experimental results confirmed the complete conversion of PP, with no relevant residues detected, and the majority of carbon nanoparticles manifested as carbon nanospheres.

Carbon nanosheets

-

Carbon nanosheets are key components in functional carbon material systems due to their two-dimensional extensibility and atomic thickness. Their physical properties include an ultra-thin planar structure (lateral dimensions 1–100 μm, thickness 0.5–10 nm) and tunable interlayer stacking modes (AA/AB/disordered stacking), conferring ultrahigh specific surface area and in-plane anisotropic conductivity.

Liu and colleagues efficiently converted polypropylene (PP) waste into ultrathin carbon nanosheets (CNS, thickness 4–4.5 nm) with an ultrahigh carbon conversion rate of 62.8% using a ferrocene/sulfur molecular-level catalytic synergistic system in a confined reaction environment (Fig. 6b)[38]. After activation treatment, the hierarchical porous activated carbon nanosheets (ACNS) exhibited exceptional structural characteristics—an ultrahigh specific surface area of 3,200 m2/g and a hierarchical pore volume of 3.71 cm3/g (mesopore fraction 78%)—which endowed them with superior electrochemical performance.

Hou and colleagues transformed waste plastics into high-performance metal-free carbon-based catalysts via a template strategy[39]. Employing g-C3N4 as a template agent for co-pyrolysis with plastic waste, they successfully prepared nitrogen-doped carbon materials (NGXs) with a graphene-like nanosheet structure. The NGXs exhibited an enhanced specific surface area of 1,043.4 m2/g and a high nitrogen doping level of 17.53 at%. This unique structure demonstrated ultrafast kinetics in the peroxydisulfate activation degradation of sulfadiazine, achieving complete pollutant removal within 180 s.

Carbon quantum dots

-

Carbon quantum dots (CQDs) represent a groundbreaking material in nano-optoelectronics, leveraging quantum confinement effects and surface state-dominated luminescent properties. Their physical characteristics include an ultrasmall size (particle size 1–10 nm) and a core-shell structure, which confer precisely tunable fluorescence emission spectra and ultrahigh fluorescence quantum yield.

Chaudhary et al.[40] converted three types of waste plastics—polyethylene plastic bags (P-CDs), plastic cups (C-CDs), and polyester bottles (B-CDs)—into fluorescent carbon quantum dots (C-dots) via pyrolysis (Fig. 6c). Spectral analysis indicated that differences in precursor molecular structure significantly influenced the optical properties of the C-dots. Carboxyl/hydroxyl surface functionalization endowed the materials with excellent water dispersibility, a size distribution of 5–30 nm, and a characteristic absorption band at 260 nm.

Takahashi et al.[41] further achieved directional conversion of waste polyolefins (PE, PP) into multifunctional carbon dots (PCDs) using a phenylenediamine-assisted hydrothermal method. Initially, the polyolefins underwent thermal oxidative degradation to form oxygen-containing functional group precursors. Subsequently, these precursors underwent dehydration, condensation, and amination reactions with phenylenediamine isomers, resulting in PCDs emitting blue/green/yellow light with significantly enhanced quantum yields. This technique overcomes the chemical inertness limitation of polyolefins, enabling the creation of zero-dimensional nanomaterials through the construction of active structural units. Compared to traditional organic solvent methods, this eco-friendly process utilizing hydrogen peroxide solvent offers greater environmental advantages. The resulting PCDs exhibited ppm-level sensitivity for detecting Fe3+ ions in aqueous solutions.

Soft carbon

-

Soft carbon, characterized by its graphitizable liquid-crystalline mesophase transformation behavior, serves as a critical component in energy storage material systems. Its structural features involve thermally driven layered ordering, which imparts gradient-tunable electronic conductivity and unique ion intercalation behavior.

Hong et al. recovered two typical waste plastics, HDPE and LDPE, and synthesized soft carbon via a two-step sulfuration and carbonization process[42]. Their findings indicate that soft carbon synthesized this way holds significant promise for application as an anode in lithium-ion batteries. Furthermore, experimental results demonstrated that electrodes derived from HDPE exhibited more stable capacity retention compared to those derived from LDPE.

He et al. synthesized soft carbon from polyvinyl chloride via a one-step method and investigated the effect of carbonization temperature on product quality. The results demonstrated that soft carbon prepared at 800 °C exhibited abundant carbon defects, delivering a high capacity of 302 mAh/g when applied in potassium-ion batteries[61] (Fig. 6d).

-

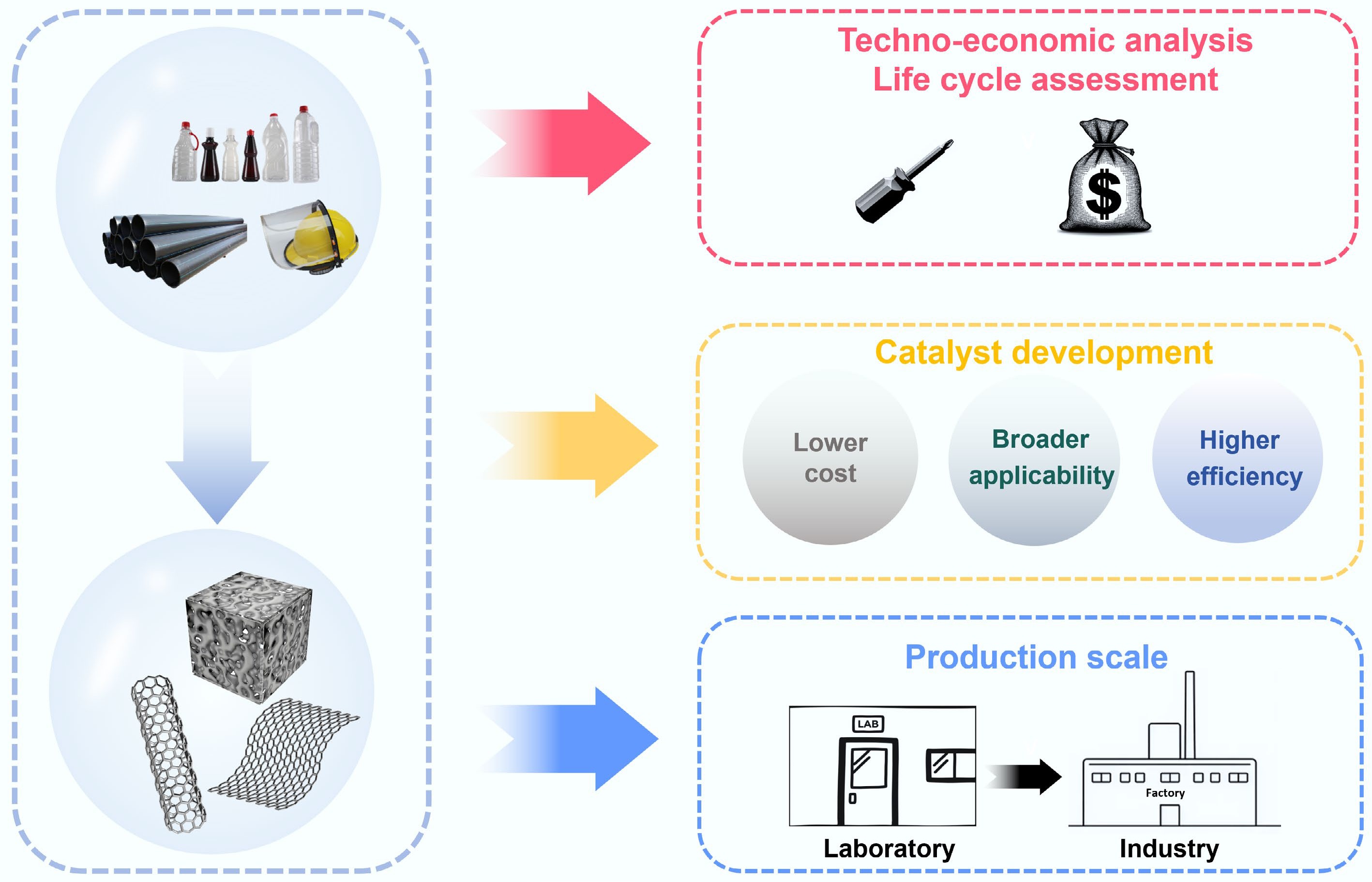

Having clarified the unique properties of waste plastics (PE, PS, PP, PET, PVC) as feedstocks and the structural and performance requirements of the target functional carbon materials (carbon nanotubes, graphene, porous carbon, carbon nanospheres, carbon nanosheets), the core bridge lies in efficient and controllable conversion processes. This section will systematically analyze the key technological routes currently employed to achieve this 'waste-to-wealth' transformation. The choice of conversion process directly determines the type of the target carbon material (e.g., whether carbon nanotubes grow or porous carbon forms), the microstructure (such as tube diameter, sheet thickness, pore size distribution), surface chemistry (functional groups, doping state), and ultimately the performance characteristics. These, in turn, affect the material's efficacy in subsequent environmental and energy applications[63]. The following sections will focus on discussing the principles, characteristics, applicable plastic ranges, and regulatory mechanisms on product structure for several representative processes, including: High-Temperature Pyrolysis, Catalytic Pyrolysis, One-Pot Synthesis, Template Method, Microwave assisted pyrolysis technology, Flash Joule Heating, and some emerging technologies. This aims to elucidate the intrinsic relationship between process-structure-performance.

Some representative methods for preparing functional carbon materials from waste plastics are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Comparison of different methods for preparing functional carbon materials using waste plastics

Method Types of plastics Reaction conditions Reaction

timeSpecific surface area (m2/g) Main carbon products Carbon recovery (%) Application Ref. Direct pyrolysis PET 5 °C/min to 600 °C 1 h 637 Porous carbon 21.7 CF4 adsorption [64] PE 5 °C/min to 700 °C 3 h 157 Porous carbon 80 Sodium-ion batteries [65] Catalytic pyrolysis HDPE 500 °C

(pyrolysis section)

800 °C

(catalytic section)− − Carbon nanotubes 27 − [66] LDPE − − Carbon nanotubes 28 − PP − − Amorphous carbon 39.5 − PS − − Amorphous carbon 2 − PET − − Amorphous carbon 1.92 − LDPE 15 °C/min to 500 °C 50 min − Carbon nanotubes 32 − [67] PP 15 °C/min to 500 °C 50 min − Carbon nanotubes 30 − PS 15 °C/min to 500 °C 50 min − Carbon nanotubes 38.26 − PET 15 °C/min to 500 °C 50 min − Amorphous carbon 3.01 − PVC 15 °C/min to 500 °C − − Carbon nanotubes 36.5 − [68] One-pot synthesis PET 600 °C 1 h 1,263 Porous carbon − Carbon dioxide adsorption [69] PVC 5 °C/min to 700 °C 30 min 1,922 Carbon nanotubes/

porous carbon89.68 − [70] Template method PS 700 °C 1 h 2,100 Porous carbon − Supercapacitor [71] PET 850 °C 2 h 421 Porous carbon − Reductive alkylation reaction [72] Microwave-assisted pyrolysis PP 800 °C − − Carbon nanotubes − − [73] Mix plastic 1,000 W 3−5 min − Carbon nanotubes − − [74] Flash joule heating HDPE − 1−3 s − Carbon nanotubes − − [75] HDPE 208 V (current increases

from 0.1 to 25 A)50 s 874 Graphene − Hydrogen evolution reaction catalyst [76] High-temperature pyrolysis

-

High-temperature pyrolysis serves as a fundamental plastic treatment technology. It involves inducing the breakdown and reorganization of plastic macromolecular chains under an inert or oxygen-deficient atmosphere at elevated temperatures (typically > 400 °C). Key parameters include the plastic type, pyrolysis conditions (temperature/ramp rate/residence time, etc.), and reactor configuration. These factors collectively determine the morphology (e.g., porous carbon, carbon nanotubes), and key characteristics (specific surface area, pore structure, surface chemistry) of the carbon materials in the product[77,78].

Direct pyrolysis

-

Direct high-temperature pyrolysis of waste plastics is a thermochemical conversion technique conducted in an oxygen-free or oxygen-deficient environment. By applying high temperatures, it causes the cleavage and decomposition of plastic macromolecules, ultimately generating gaseous hydrocarbons, liquid oil (pyrolysis oil), and solid residue (pyrolysis char/coke). The core of this process lies in excluding oxygen to prevent combustion, thereby promoting macromolecular cracking and recombination.

Yuan and colleagues recovered mineral water bottles (PET) as feedstock[64]. Direct pyrolysis at 600 °C for 1 h under a nitrogen atmosphere yielded a porous carbon, which, after activation treatment, exhibited good selectivity and regenerability in carbon tetrafluoride (CF4) adsorption.

During pyrolysis, researchers have explored incorporating auxiliary agents to enhance the quality of the resulting carbon materials. For example, Belo and colleagues mixed PET and polyacrylonitrile (PAN) and carbonized the mixture at 800 °C under a helium atmosphere. They found that the addition of PAN increased the yield of porous carbon and simultaneously enhanced its chemical properties[79].

Tang and colleagues developed a sulfur-assisted pyrolysis technique[65]. By utilizing sulfur atoms to form in-situ covalent crosslinks with polymer chains, creating thermally stable intermediates, they effectively suppressed volatile cracking. This achieved an 85% carbon recovery rate. The resulting sulfur-doped carbon material exhibited uniformly distributed sulfur, which expanded the interlayer spacing, endowing it with excellent sodium ion storage performance. This method also allows for the direct treatment of mixed plastic waste.

In recent years, machine learning has been widely applied in predicting material properties, providing important guidance for experimental design[80]. Many researchers have used machine learning to assist in optimizing various parameters of plastic pyrolysis[81]. For instance, Dai et al. combined typical experiments with machine learning to study the characteristics of regenerated carbon fiber (rCF) obtained from the pyrolysis of carbon fiber reinforced plastic (CFRP). They have developed a random forest machine learning model optimized using a particle swarm optimization algorithm based on 336 data points, and applied it to determine the structural parameters of carbon fiber reinforced plastics under various pyrolysis and oxidation conditions, effectively predicting the recycling conditions of various rCFs[82].

In addition to direct pyrolysis of plastics alone, researchers have also discovered that co-pyrolysis of waste plastics with biomass materials can influence carbon material characteristics[83]. Li et al.[84] conducted sequential pyrolysis experiments on cellulose and polyethylene terephthalate (PET). They found that the hydrocarbon-rich molecules generated from PET enhanced the crystallinity of amorphous carbon on the surface of cellulose-derived char. Concurrently, these hydrocarbon-rich molecules are deposited onto the surface of the cellulose char, improving the thermal stability of the biocarbon and enhancing its hydrophilicity.

Catalytic pyrolysis

-

Although direct high-temperature pyrolysis provides a foundational pathway for converting waste plastics into carbon-based materials, its pyrolysis process typically relies on high-temperature driving, demanding high energy efficiency. The resulting char solid-phase product often possesses a relatively disordered internal structure (primarily amorphous carbon), with limited tunability over specific surface area and pore structure. It usually requires post-activation treatment to meet the high surface area demands for adsorption or energy storage applications. More critically, its selectivity towards specific target products is weak, making it challenging to efficiently guide the pyrolysis products of plastic macromolecules towards specific, high-value ordered carbon nanostructures (such as carbon nanotubes or nanosheets) under conventional pyrolysis conditions. To overcome these challenges and significantly enhance the conversion efficiency of plastics into high-functional carbon materials, catalytic pyrolysis technology—which introduces efficient catalysts to regulate reaction pathways—has emerged and rapidly become a focal point of industry research.

The core of catalytic pyrolysis lies in the ability of specific catalysts to intervene in the microscopic processes of plastic cracking and reorganization. By altering the thermodynamics and kinetics of reaction intermediates, the product distribution is optimized and the quality of the target carbon materials is elevated.

The type of plastic significantly influences the product characteristics. Dai and colleagues used five plastics—high-density polyethylene (HDPE), low-density polyethylene (LDPE), polypropylene (PP), polystyrene (PS), and polyethylene terephthalate (PET)—as carbon precursors[66]. Employing a tandem catalytic pyrolysis-chemical vapor deposition (CVD) process, they grew carbon materials onto nickel foam substrates. Results showed that polyolefin plastics (HDPE/LDPE/PP), due to their single-stage decomposition behavior and high alkane content, yielded highly crystalline carbon nanomaterials on the Ni foam, simultaneously achieving high hydrogen selectivity and low-impurity liquid oil production. In contrast, PS, dominated by aromatic hydrocarbons in its pyrolysis products, generated 84 wt% high-value aromatic oil. PET, however, led to 42% amorphous carbon deposition and suppressed hydrogen yield due to oxygen-containing COx byproducts. Similar patterns were observed in the research conducted by Yao et al[67].

Borsodi et al.[85] conducted a comparative analysis of the conversion of six plastic types (PE/PP/PS/PA/PVC/MPW) under the influence of Fe/Co catalysts, thereby confirming that municipal mixed plastics yielded the highest gas production, while polypropylene (PP) yielded the optimal amount of oil.

Cai et al.[86] conducted a study to ascertain the disparities in catalytic pyrolysis product distributions from disparate waste plastics utilizing an Fe/Al2O3 catalyst. The experimental results indicated that polyolefin plastics, including PP, HDPE, and LDPE, were responsible for the generation of over 40 wt% of gaseous products. In contrast, high-impact polystyrene (HIPS) and general-purpose polystyrene (GPPS) produced 49.4 wt% and 48.7 wt% solid deposits, respectively, with their gaseous products containing up to 74.1 vol% hydrogen. With regard to liquid products, all plastics yielded approximately 20 wt% oil, primarily composed of aromatic hydrocarbons within the C8–C16 carbon number range. A thorough analysis of the solid deposits was conducted, which confirmed the presence of carbon nanotubes (CNTs), with those from polyolefin systems exhibiting higher crystallinity. The selectivity differences stem from the intrinsic plastic structure: the aromatic ring structure of polystyrene promotes dehydrogenation and inhibits graphitic carbon deposition, while the linear alkane nature of polyolefins favors the formation of highly crystalline CNTs.

Transition metal catalysts (Fe/Ni/Co) are crucial for the directional synthesis of carbon materials. In a pioneering study, Wu and colleagues employed a novel catalyst system comprising MgO-supported monometallic Fe[87]. Using a two-stage pyrolysis-catalysis reactor, they successfully achieved the efficient conversion of five plastic polymers—PP, LDPE, HDPE, PS, and polycarbonate (PC)—into high-quality single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs). Catalytic characterization confirmed that Fe species were highly dispersed on the MgO support surface, and their reducibility provided active sites for CNT growth. The catalyst's unique strong metal-support interaction (SMSI), synergizing with high carbon solubility, effectively maintained the high carbon flux demand from polymer cracking, enabling continuous SWNT growth. Cai et al.[88] utilized an Al2O3-supported Fe catalyst for the catalytic pyrolysis of waste plastics, producing iron-doped carbon nanotubes (Fe-CNTs) that exhibited excellent performance in the oxygen reduction reaction. Abbas et al. used zeolite-supported iron oxide to convert soft plastic packaging waste into multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs)[89]. After functionalization with nitric acid to introduce surface oxygen-containing functional groups, this material demonstrated significantly superior capacitive properties compared to commercial MWCNTs in electrochemical tests, attributed to its higher electrochemical activity and faster charge transfer rate.

Yao et al.[90] synthesized Fe-Ni bimetallic catalysts by sol-gel and impregnation methods for the catalytic pyrolysis of PP to generate CNTs. They further investigated the effect of different catalytic temperatures, identifying 700 °C as the critical threshold for CNT growth; below this temperature, inferior products dominated by amorphous carbon were formed. Within the temperature range of 700–800 °C, directional CNT growth was observed. However, increasing the temperature beyond this range produced only a marginal increase in yield without substantially altering the degree of graphitization.

In addition to the metal elements in the catalyst, the catalyst support also plays a critical role in the CNT formation process. Yao and colleagues investigated the effect of catalyst support on CNT synthesis from waste plastics[91]. They prepared four different bimetallic catalysts by loading Ni–Fe onto four distinct porous materials. The results showed that the Ni–Fe/MCM-41 system achieved a record carbon conversion rate of 55.60 wt%, benefiting from the advantages of its hierarchical mesopores. Its performance significantly surpassed that of supports dominated by micropores, such as ZSM-5, Beta, and NKF-5. This superiority is attributed to the high specific surface area of MCM-41, which ensures good dispersion of Ni–Fe alloy particles and provides more active sites. Meanwhile, the mesoporous channels in Ni–Fe/MCM-41 enhance the diffusion efficiency of pyrolysis volatiles, whereas the large metal particles on Beta promote irregular carbon deposition. Characterization confirmed that CNTs produced using the MCM-41 support exhibit the highest degree of graphitization.

Biogenic catalysts exhibit dual effects in catalytic pyrolysis experiments. Wang et al. investigated the carbon deposition mechanism during plastic catalytic pyrolysis using woodchip-derived biochar as the catalyst[92]. Catalyzing pyrolysis gases from PS and PE under atmospheric pressure without added metals, they observed the differentiated growth of three types of carbon nanomaterials for the first time: ring-rich PS pyrolysis gases (900 °C) induced the formation of bulky amorphous carbon (BAC), monolayer amorphous carbon (MAC), and carbon nanofibers (CNFs), while chain-rich PE pyrolysis gases formed only BAC and CNFs. The carbonophilic surface of the biochar, by forming stable C-C bonds, promoted significant carbon deposition (up to 164 mg/g in the PS system). In-depth mechanistic studies revealed that MAC formation depended on the synergistic effect of undecomposed aromatic rings in PS pyrolysis gas and the high-temperature environment. CNF growth was directly related to the sp2 hybridized carbon content on the biochar surface, but the limited sp2 content resulted in lower CNF yields. Veksha et al. studied the inhibitory effect of biogenic impurities on the catalytic conversion of polyolefins into MWCNTs and hydrogen. Experiments showed that three types of biomass impurities—coconut coir, sewage sludge, and shellfish (9.1 wt%)—significantly reduced MWCNT yield (pure polyolefin system: 33% ± 7%, impurity systems: 16%–20%)[32]. Gas composition analysis confirmed decreased hydrogen concentration accompanied by methane and ethylene accumulation, attributed to gas-phase byproducts from the biomass interfering with metal active sites. Transmission electron microscopy confirmed that all three impurities altered the carbon growth pathway, leading to carbon nanofiber contamination, but the intrinsic properties and surface chemistry of the formed CNTs remained largely unchanged.

Addressing chlorine-containing plastics, Ma and colleagues developed a low-temperature aerobic pretreatment technology. Operating in the low-temperature range of 260–340 °C with controlled oxygen concentration (optimum 20%), this process achieved > 99% chlorine removal via selective dechlorination reactions[68]. Simultaneously, it facilitated the directional conversion of chlorine-containing functional groups (C-Cl, -CH2-CHCl-) in the solid product to oxygen-containing groups (C=O, RCHO). Subsequent catalytic pyrolysis of this oxygen-enriched carbon intermediate over an FeAl2O4 catalyst achieved over 60% selectivity towards carbon nanotubes (CNTs). The graphitization degree of these CNTs surpassed that of CNTs derived from traditional PP and HIPS.

One-pot synthesis

-

While pyrolysis and catalytic pyrolysis provide the crucial foundation for converting waste plastics into functional carbon materials, significantly expanding the range and performance ceiling of target products, the multi-step operations involved—whether the activation step required after conventional pyrolysis, or the catalyst separation and recovery often needed after catalytic pyrolysis (including pretreatment, pyrolysis/catalytic pyrolysis, product separation, and post-activation)—inevitably increase process complexity, energy consumption, time costs, and may introduce additional material consumption (e.g., chemical activators used in separate steps) or material loss (e.g., catalyst entrainment or carbon powder loss during separation).

Facing this challenge, researchers strive to seek more efficient and intensified solutions that integrate multiple key steps into a single reactor for a 'one-step' process. This pursuit of process simplification and intensification has directly led to the emergence and development of the 'One-Pot Synthesis' strategy in the field of waste plastic valorization. One-pot synthesis cleverly combines the key components like plastic feedstock, catalyst, activator/templating agent/dopant into one reaction system. Through a coherent operational sequence (often including melting, mixing, pyrolysis, and activation steps), it accomplishes the direct preparation of functional carbon materials from precursors, maximizing operational simplification, reducing energy consumption and costs, and potentially enabling unique structural control over the final material.

Yuan and colleagues employed a one-pot synthesis strategy, simultaneously achieving KOH activation and urea nitrogen doping at 700 °C to convert waste PET plastic into nitrogen-doped microporous carbon, which exhibited good adsorption performance in CO2 capture applications[69]. Material analysis indicated that the synthesized microporous carbon possessed a large specific surface area, facilitating synergistic enhancement of adsorption by surface nitrogen/oxygen functional groups.

Zhou and colleagues adopted a one-pot dechlorination-carbonization process to efficiently convert polyvinyl chloride (PVC) into porous carbon. They first used ZnO or KOH as chlorine fixatives to convert organic chlorine into Zn2OCl2·2H2O or KCl crystals, significantly reducing residual chlorine[70]. The dechlorinated polyolefin-like intermediate was then carbonized, yielding 80.80 wt% solid product, of which the carbon material constituted 83.13%. The choice of chlorine fixative allowed tuning of the carbon material's morphology and structure: the ZnO system produced millimeter-sized highly graphitized carbon spheres, whereas the KOH system formed porous carbon with a specific surface area of 1,922 m2/g rich in oxygen-containing functional groups.

Template method

-

The one-pot synthesis strategy significantly simplifies the conversion of waste plastics into functional carbon materials by integrating multiple reaction steps and functional components, offering comprehensive advantages in efficiency, cost, and potential structural control. However, its primary objective is directed more toward process-level intensification and efficiency.

When the goal shifts to the precise design and customization of the carbon material's microstructure—such as achieving a highly ordered mesoporous structure, specific pore-size distribution, uniform spherical morphology, or controllable layer thickness—relying solely on the inherent pyrolysis characteristics of the plastic and the effects of thermal or chemical fields is often insufficient. To enable precise control and programmable construction of carbon morphology and pore arrangement at the nano- to microscale, a more 'design-oriented' strategy—the template method—has been introduced into the synthesis of waste-plastic-derived carbon materials[93].

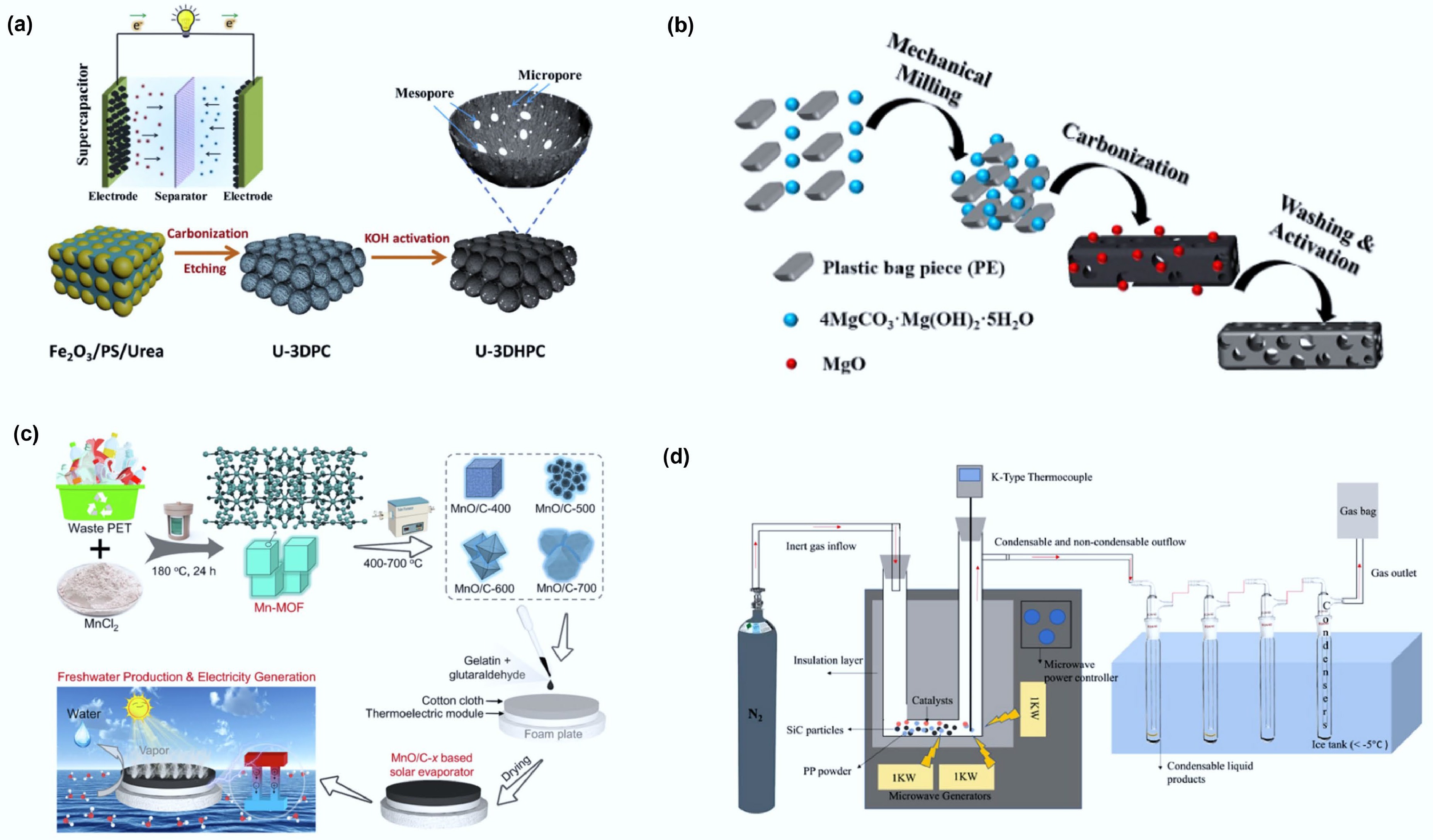

The template method can be categorized into hard templating and soft templating. Hard templating typically employs solid materials with rigid structures as templates (e.g., silica, iron oxide, zeolites). For example, Ma and colleagues used iron oxide simultaneously as both catalyst and template, combined with KOH activation, to convert polystyrene waste into three-dimensional hierarchical porous carbon (3DHPC) (Fig. 7a)[71]. Employing a urea-based nitrogen-doping strategy further enhanced the porosity, yielding a high-performance material (U-3DHPC). Yu and colleagues used magnesium oxide as a template to convert PET into nanoporous carbon (NPC)[72]. Their experiments showed that when the NPC pore size was below 14 nm, the catalytic activity increased markedly with increasing pore size.

Figure 7.

(a) Schematic illustration of the synthetic process for the preparation of 3D hierarchically porous carbon. Reproduced with permission[71] (Copyright 2020 Elsevier). (b) Schematic illustration of the fabrication process for PE-HPC900NH3. Reproduced with permission[94] (Copyright 2019 Elsevier). (c) Scheme of preparing flexible MnO/C-x membrane for integrated interfacial solar evaporation and thermoelectric power generation. Reproduced with permission[95] (Copyright 2023 Elsevier). (d) Schematic diagrams of the microwave pyrolysis reactor. Reprinted with permission[73] (Copyright 2024 American Chemical Society).

Soft templating uses dynamic soft aggregates formed through molecular self-assembly as templates. For example, Lian and colleagues employed basic magnesium carbonate pentahydrate as a soft template to synthesize porous carbon with a high specific surface area and a distinctive mesoporous structure from polypropylene (PP) as the carbon source (Fig. 7b)[94]. The resulting material exhibited excellent capacitive performance and cycling stability.

The template method shows exceptional ability to guide waste-plastic-derived carbon materials into precise, ordered structures by ingeniously introducing exogenous templating agents. However, its heavy dependence on artificially pre-synthesized templates presents significant challenges: the synthesis of the templates themselves (e.g., highly ordered mesoporous silica) is often complex and costly; achieving uniform infiltration of the carbon source into the template and its complete removal after carbonization poses technical difficulties and potential risks. These limitations restrict its scalability for large-scale applications.

To overcome the operational complexity and environmental concerns associated with conventional template methods—while retaining or even enhancing control over carbon structures—researchers have increasingly turned to metal–organic frameworks (MOFs). MOFs feature intrinsic nanoscale cavities and tunable chemical compositions. Their key advantage lies in integrating the template and carbon source at the molecular scale, providing a more unified pathway for converting plastics into carbon materials.

Al-Enizi and co-workers employed waste polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles as a carbon source to synthesize MOF-derived materials[96]. They successfully prepared composites of ZnO and Co3O4 nanoparticles embedded in mesoporous carbon (ZnO@MC and Co3O4@MC), both of which exhibited exceptionally high surface areas and outstanding electrochemical performance. Zhang et al. also used PET as a precursor to construct a lanthanide-based MOF (Tb-BDC) via controlled hydrolysis[97].

Similarly, Fan and colleagues utilized waste polyester (PET) to prepare a cubic Mn-MOF precursor (14−27 μm) through a solvothermal process (Fig. 7c)[95]. Controlled pyrolysis at 400−700 °C yielded MnO/C hybrid nanoparticles with tunable morphologies. When integrated into a thermoelectric device under three-sun illumination, the material delivered an output voltage of 330 mV, a power of 4.65 mW, and a power density of 2.9 W/m2, enabling efficient recovery of evaporation waste heat.

Microwave-assisted pyrolysis (MWP)

-

Although MOFs enable precise structural control and significantly simplify the conversion process, traditional pyrolysis, catalytic pyrolysis, and even MOF-derived carbonization—which rely on heat transfer via convection and conduction from thermal furnaces—are inherently limited by high energy consumption and slow processing rates. Moreover, the slow heating process can promote undesirable side reactions.

To address these limitations in energy efficiency and reaction kinetics, researchers have turned to advanced technologies that utilize electromagnetic field energy, such as microwave-assisted pyrolysis (MWP). The key innovation of MWP lies in its direct coupling of high-frequency electromagnetic waves with matter, inducing dielectric polarization and ionic conduction at the molecular scale. This mechanism enables rapid, selective internal heating of the reaction system, providing an efficient, energy-saving, and fast-reaction pathway for converting waste plastics into functional carbon materials with unique structures and properties[98].

The introduction of metal catalysts can significantly enhance conversion efficiency. Li and colleagues synthesized five different Fe-based catalysts (Co-Fe, Ni-Fe, Al-Fe, Co-Al-Fe, Ni-Al-Fe) and applied them in a microwave irradiation process for treating waste polypropylene plastic (Fig. 7d)[73]. Experimental results showed that the Al-Fe catalyst exhibited the best performance: compared to non-catalytic experiments, gas yield increased from 19.99 wt% to 94.21 wt%, and high-value carbon nanotubes were produced. Compared to conventional pyrolysis, microwave pyrolysis yielded four times more hydrogen and demonstrated higher economic feasibility. Shoukat and colleagues also conducted a series of studies on three different ferrite catalysts—nickel ferrite (NiFe2O4), zinc ferrite (ZnFe2O4), and magnesium ferrite (MgFe2O4)—during microwave pyrolysis of plastics[99]. The study indicated that MgFe2O4, with its moderate strong magnetic properties and catalytic activity, formed a synergistic effect. Compared to single-metal oxide catalysts, it could crack organic molecules at relatively lower temperatures, effectively suppressing tar and char formation.

Jiang et al. used waste PET as a raw material and converted it into a cobalt oxide/porous carbon composite catalyst rich in oxygen vacancies (S0.3-Co@P2C) via microwave-assisted pyrolysis[100]. This material demonstrated good performance in persulfate activation for carbamazepine degradation. Material characterization revealed that the material possessed a larger specific surface area, and more active sites after microwave treatment.

Xie et al. introduced a porous nanosheet catalyst on the basis of microwave-assisted plastic pyrolysis[101]. Experimental results indicated that this two-dimensional porous structure significantly improved the growth space for carbon nanotubes, yielding highly graphitized multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) with a production rate of 571 mg CNT per gram of LDPE. The performance enhancement was primarily attributed to the Fe2O3 particles on the composite promoting C-H bond cleavage, facilitating H2 production, and CNT growth.

Jie and colleagues utilized an Fe-based catalyst (FeAlOx) to efficiently convert shredded plastic waste into hydrogen and multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) within 30–90 s[74]. The technique achieved a hydrogen yield of 55.6 mmol/gplastic (reaching 97% of the theoretical hydrogen mass), with a hydrogen concentration of about 90 vol% in the effluent gas. Continuous feeding achieved a carbon production rate of 1,560 mg C/gplastic/gCatalyst, with MWCNT purity exceeding 92 wt%.

Differing from the single-layer microwave pyrolysis setups mentioned above, Wang and colleagues proposed a Double-Layer Microwave-assisted Pyrolysis (DLMP) process for the efficient conversion of waste polyethylene (PE) into hydrogen and carbon nanomaterials[102]. This method significantly enhanced hydrogen generation efficiency by covering the primary catalyst-PE mixture layer with a secondary catalyst layer. Experimental results showed that using DLMP, various catalyst systems achieved hydrogen yields exceeding 60 mmol/g PE. The FeAlOx catalytic system performed best, with a yield of 66.4 mmol/g PE, equivalent to 93% of PE's theoretical maximum hydrogen potential.

Zafar and colleagues further proposed an ambient-pressure microwave plasma process—a chemical synthesis technique utilizing microwave energy to generate plasma from gases at atmospheric pressure[20]. This method combines the advantages of efficient microwave energy transfer and the high reactivity of plasma. Using 500 W of power, the researchers efficiently converted crushed PE dropper bottles (polyethylene microplastics) into graphene.

Flash Joule Heating (FJH)

-

Microwave-assisted pyrolysis, with its unique molecular-level energy coupling mechanism, successfully enables directional control of plastic cracking pathways and significant process acceleration, offering an efficient and green route for plastic waste conversion. However, its physical upper limit for energy transfer is still constrained by the coupling depth of electromagnetic waves with matter and spatial field uniformity, limiting its application in ultrafast reactions requiring extreme energy flux (e.g., millisecond-scale complete reactions).

To overcome the limitations of conventional thermochemical methods (including microwave heating) in terms of temperature ramp rate and energy density, and to explore the instantaneous evolution behavior of matter under extreme non-equilibrium conditions, researchers have developed Flash Joule Heating (FJH). By applying an instantaneous ultrahigh current density (> 1,000 A/mm2) to conductive precursors (or composite systems), FJH induces an intense Joule heating effect within milliseconds to hundreds of milliseconds, creating an ultrafast high-temperature environment with temperature ramp rates reaching 105~106 K/s and peak temperatures exceeding 3,000 K[75].

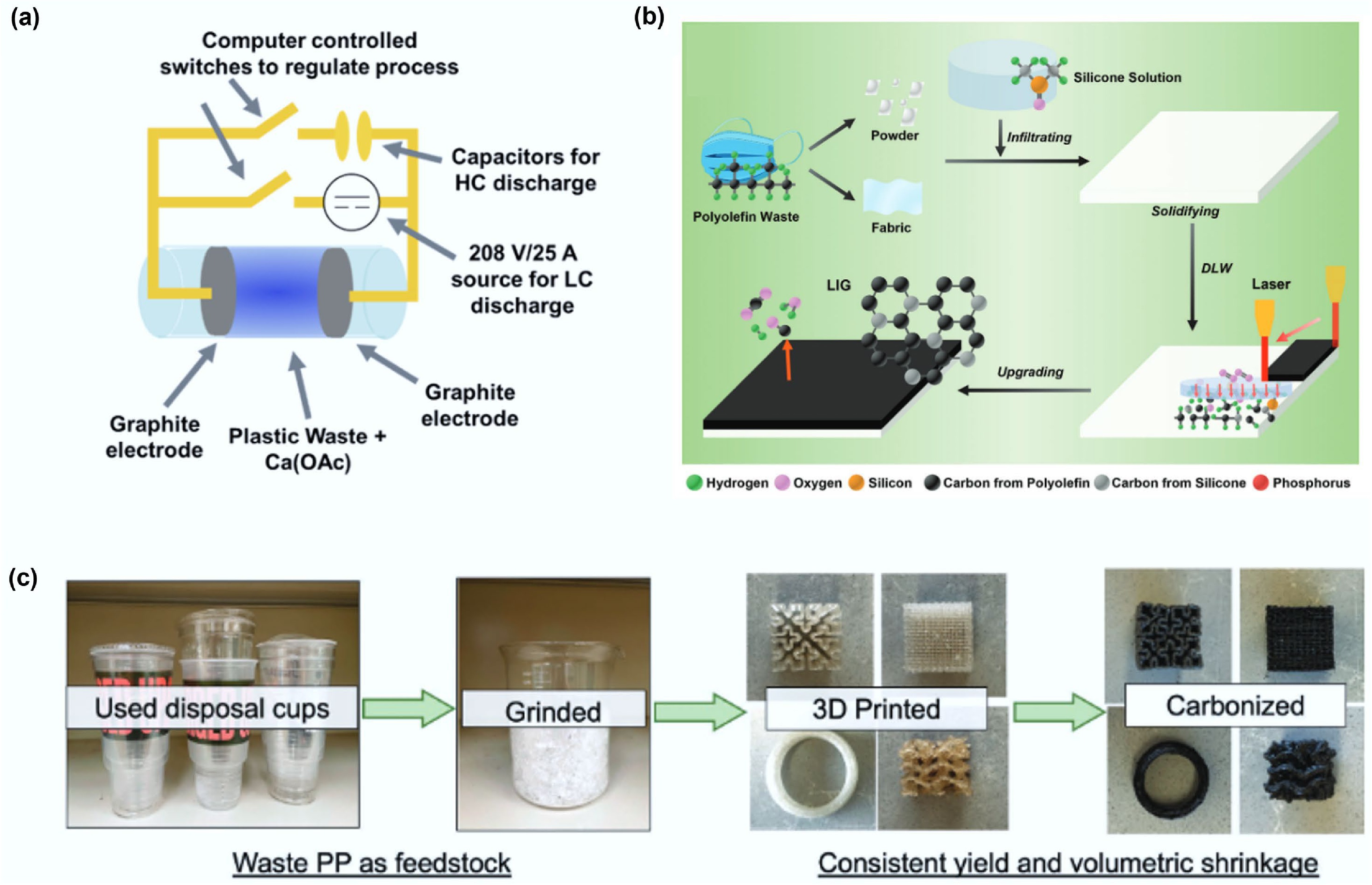

Wyss and colleagues utilized Flash Joule Heating (FJH) technology to achieve the directional conversion of mixed plastic waste into hierarchically wrinkled flash graphene (HWFG) (Fig. 8a)[76]. This technology simultaneously induces pore construction (coexistence of micro/meso/macropores) and surface wrinkling via an in-situ salt decomposition mechanism, resulting in a specific surface area as high as 874 m2/g. Spectroscopic characterization confirmed its high defect concentration and turbostratic graphene layer stacking characteristics.

Figure 8.

(a) An FJH schematic composed of a 30 A, 208 V rectified power supply and a 128 mF capacitor allowing for LC and HC heating to be used in tandem. Reprinted with permission[76] (Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society). (b) Schematic illustrations of the processes and applications of upgrading polyolefin plastic waste into LIG using SA-DLW. Reproduced with permission[103] (Copyright 2024 John Wiley and Sons). (c) Upcycling scheme of PP waste to carbons, demonstrating feedstock, printed parts and final structured carbon materials. Reproduced with permission[104] (Copyright 2023 John Wiley and Sons).

Other emerging processes

-

Beyond mainstream technological pathways, emerging processes continuously expand the boundaries for the valorization of waste plastics.

Laser-Induced Graphene (LIG) Conversion: Qu and colleagues developed a silicone-assisted direct laser writing (SA-DLW) technique to achieve efficient conversion of polyolefin waste plastics into porous laser-induced graphene (LIG), with conversion rates ranging from 33.1% to 55.8%[103]. By infiltrating silicone into the polyolefin, this technique effectively delays the laser ablation process and provides an additional carbon source, a mechanism validated by molecular dynamics simulations and experiments. The resulting LIG possesses a porous structure and excellent conductivity, making it suitable for constructing high-performance energy storage and sensing devices (Fig. 8b). This is a universal technology that can be used to treat various forms of plastic waste, providing an effective path for high-value conversion of plastic waste.

3D Printing-Derived Structured Carbon: Smith and colleagues developed a simple and scalable method to produce complex structured carbon from commodity PP (Fig. 8c)[104]. Researchers first fabricated a PP plastic matrix via 3D printing. Subsequent sulfonation introduced fine cracks into the matrix. After carbonization, a high carbon recovery rate of up to 62 wt% was achieved. Performance characterization demonstrated that this honeycomb-like carbon structure, despite containing crack defects, exhibits exceptional mechanical strength, with a load-bearing capacity per unit density exceeding that of the precursor by over 5,300-fold. It also possesses rapid joule response characteristics. This method can be applied to the production of various carbon materials with complex structures.

While the aforementioned two emerging technologies enable more precise control over the functional carbon materials, they continue to face significant challenges in achieving industrial-scale production.

The conversion technology of waste plastics into functional carbon materials has broken through from high-throughput conversion of basic pyrolysis/catalytic pyrolysis to intensive one pot process; from precise structural design using template method to molecular level template carbon source fusion of MOFs; from the energy field driven innovation of microwave/Joule flash to the emergence of new technologies such as laser direct writing and 3D printing. It can be seen that the current technology is showing the characteristics of continuous deepening of process integration, continuous improvement of structural control accuracy, and continuous improvement of energy efficiency. However, large-scale applications still face challenges such as catalyst cycling, compatibility with complex plastic components, and development of continuous equipment.

-

Converting waste plastics into various high-value carbon functional materials presents an effective, low-cost pathway for producing valuable products, offering greater economic and environmental benefits compared to traditional carbon material preparation methods. Furthermore, waste plastic-derived functional carbon materials typically possess tunable pore topology, modifiable surface chemistry, and excellent charge transport capabilities, making them exceptionally suitable for applications in environmental and energy fields.

In the environmental domain, they serve as efficient adsorbents and catalysts for targeted remediation of multi-media environmental risks, including gaseous pollutants (e.g., CO2), organic micropollutants (e.g., tetracycline antibiotics), electromagnetic radiation, and heavy metal ions. In the energy domain, leveraging their three-dimensional conductive networks and rapid ion channels, they significantly enhance the energy-power density balance of lithium-ion batteries and supercapacitors.

Applications in the environmental field

Carbon dioxide (CO2) adsorption and capture

-

The escalating greenhouse effect has made CO2 adsorption and capture technologies a critical research focus[105]. Studies demonstrate that during the conversion of waste plastics into functional carbon materials, the use of activating agents can significantly increase the material's specific surface area, thereby optimizing its CO2 adsorption performance.

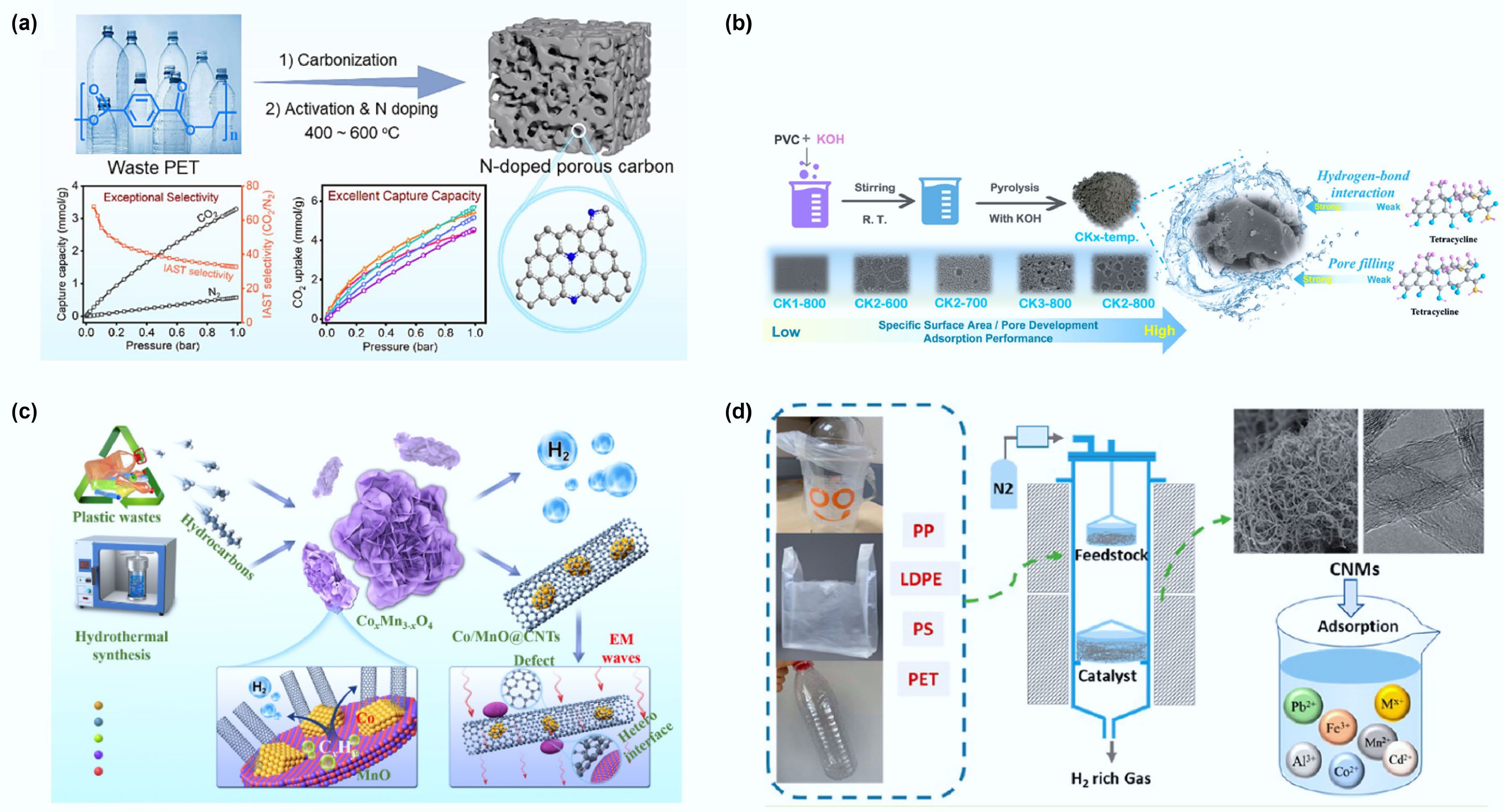

Among activating agents, KOH has proven highly effective. Yuan et al. used PET plastic bottles as raw material, successfully preparing porous carbon materials for CO2 capture via carbonization followed by KOH activation[106]. This material exhibited excellent CO2 adsorption performance under 298 K and 101.3 kPa, with a maximum uptake of 4.42 mol/kg. Additionally, the PET-derived porous carbon showed good selectivity towards N2 and CO, along with excellent cycling stability.

Moving beyond single plastics, Zhou et al. focused on converting mixed plastic waste (MPW). Researchers first treated MPW via autogenous pressure carbonization (APC), achieving a char yield of 56%[107]. Subsequently, the char was converted into high-performance porous carbon using KOH chemical activation. The study found that the KOH dosage is a key parameter for tuning the material's structure and performance.

The choice of activating agent significantly impacts porous carbon performance. Algozeeb et al. compared the effects of three activating agents (potassium hydroxide, sodium acetate, potassium acetate): while KOH effectively creates pores, it can cause excessive plastic decomposition, reducing porous carbon yield; sodium acetate and lithium acetate have limited impact on yield; potassium acetate (KOAc) demonstrated the best performance for porous carbon generation[108].

Optimizing the activation strategy is another route to enhance performance. Zhou et al. employed sodium amide (NaNH2) simultaneously as a nitrogen dopant and a low-temperature activating agent to prepare porous carbon via high-temperature pyrolysis of PET[109]. The introduction of NaNH2 effectively optimized the pore structure, significantly boosting the material's CO2 adsorption capacity (Fig. 9a). Characterization revealed that the resulting porous carbon possessed an ultrahigh specific surface area (> 2,200 m2/g), significant micropore volume (0.755 cm3/g), and was rich in nitrogen (1.39 wt%) and oxygen (19.19 wt%) functional groups. Under 1 bar adsorption conditions, the material exhibited outstanding CO2 capture performance, attributed to the synergistic effect of narrow micropore confinement and surface polar sites. The adsorption kinetics followed a pseudo-second-order model, and the material combined excellent cycling stability (no capacity decay after five cycles), high CO2/N2 selectivity, and moderate isosteric heat of adsorption.

Figure 9.

(a) Synthesis of nitrogen doped hierarchical porous carbon from polyethylene terephthalate and its adsorption performance for carbon dioxide. Reproduced with permission[109] (Copyright 2024 Elsevier). (b) Schematic diagram of the adsorption process of tetracycline using carbonization activation method to prepare PVC into porous carbon material. Reproduced with permission[110] (Copyright 2023 Elsevier). (c) Schematic fabrication procedure of the Co/MnO@CNTs nanocomposites and the working mechanism on electromagnetic waves. Reproduced with permission[111] (Copyright 2023 Elsevier). (d) Schematic diagram of carbon nanomaterials produced by pyrolysis and catalytic reforming of waste plastics for metal ion adsorption. Reprinted with permission[67] (Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society).

The choice of activation method is also crucial. Perez-Huertas et al. noted that while chemical activation (e.g., KOH/H3PO4) can achieve higher specific surface areas and larger micropore volumes, the chemical reagents used pose potential environmental pollution risks; physical activation excels in process simplicity and cost advantages. The study also found that the development of narrow micropores (< 1 nm) is a key factor determining CO2 adsorption performance[112].

Dan et al. compared the impact of microwave-assisted activation vs conventional thermal activation on porous carbon derived from pyrolyzed plastic waste[113]. Microwave assisted activation uses lower temperatures, less time, and lower energy consumption, but its activated carbon or yield (78%) is higher than traditional activated carbon (71%). Thermogravimetric analysis showed that the total weight loss of conventional samples and microwave samples was 10.0 wt% and 8.3 wt%, respectively, within the temperature range of 25–1,000 °C. Both activation pathways produced AC with typical Type I nitrogen adsorption isotherms. Thermogravimetric analysis indicated total weight losses of 10.0 wt% and 8.3 wt% for conventional and microwave samples, respectively, over 25–1,000 °C. Both activation pathways produced AC exhibiting typical Type I nitrogen adsorption isotherms. Dynamic CO2 adsorption tests (25 °C, 1 bar) showed a CO2 uptake of 1.53 mmol/g for conventional AC; equilibrium adsorption experiments under 0–50 °C and 1 bar yielded a maximum CO2 adsorption capacity ranging from 1.32 to 2.39 mmol/g. Under the same conditions, microwave-activated AC demonstrated superior adsorption performance: a dynamic uptake of 1.62 mmol/g and an equilibrium capacity range of 1.58–2.88 mmol/g.