-

Rice (Oryza sativa L.) is among the world's most important staple crops, serving as the primary food source for nearly half of the global population[1]. To meet increasing food demands driven by global population growth, nitrogen fertilizer application has become a typical practice in modern rice agriculture to boost productivity[2]. However, continuous increases in nitrogen inputs have not resulted in proportional improvements in crop yield[3,4]. Instead, the low nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) of paddy fields has rendered them a significant anthropogenic source of reactive nitrogen (Nr) gas emissions[5], contributing to a suite of adverse environmental impacts, including soil acidification[6], eutrophication[7], ozone depletion[8], and global climate change[9]. Among these emitted gases, ammonia (NH3) and nitrous oxide (N2O) are the dominant Nr emission forms from rice paddies[10]. Between 1980 and 2018, NH3 emissions from agricultural systems increased by 128%, with rice cultivation accounting for nearly one-quarter of total farmland NH3 emissions[11]. Additionally, the annual average N2O emissions from rice paddies reach 1.7 kg·ha−1, and this figure is projected to rise further[12]. While research remains limited, recent studies suggest that agricultural soils may also represent important and previously underestimated sources of atmospheric HONO and NOx[13,14].

Nr gas emissions from paddy soils are primarily governed by microbial processes, including ammonification, nitrification, and denitrification. NH3 volatilization is driven by physicochemical changes at the soil–water–air interfaces: NH4+ adsorbed onto soil colloids is first transformed into soluble NH4+ in soil solution, which subsequently undergoes conversion to NH3 and emits as a gas[15]. N2O production occurs via two pathways: (1) incomplete oxidation of hydroxylamine (NH2OH), a nitrification intermediate catalyzed by hydroxylamine oxidoreductase (HAO)[16]; and (2) denitrification, wherein NO3− and NO2− undergo stepwise reduction through nitrate reductase (NAR), nitrite reductase (NIR), and nitric oxide reductase (NOR)[17]. Similarly, NOx emissions originate from microbial nitrification, denitrification, and abiotic reactions in the soil[17−19], with NO as the dominant form. Once emitted, NO is rapidly oxidized to NO2 in the atmosphere, and the reduction of NO2− to NO by NIR represents a rate-limiting step in NO formation[20,21]. Under flooded conditions, soil HONO emissions are largely attributed to denitrification, with ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB) playing a key role[22,23]. Given that Nr emissions are regulated by complex microbial and physicochemical factors, variables such as soil pH, oxygen content, and NO2−/NO3− concentrations exert significant impacts on emission fluxes[22,24−26].

A range of strategies have been proposed to mitigate nitrogen losses from paddy fields, which include improving irrigation methods (e.g., alternate wetting and drying[27], aerated irrigation[28]), optimizing fertilization[29,30], and applying slow-release fertilizers[31,32], nitrification inhibitors[33], and urease inhibitors[34]. While these approaches have been widely adopted, their performance evaluation has predominantly focused on sustaining or improving rice yields and NUE. In contrast, relatively little attention has been paid to their effectiveness in directly reducing Nr gas emissions. This research gap highlights the need for complementary approaches that explicitly target Nr losses alongside agronomic performance. Duckweed (Lemna minor L.) is a small, floating monocotyledon adapted to static or slow-moving waters, which can be regarded as an alternative for nitrogen management, with additional ecological co-benefits. Owing to its high nitrogen uptake capacity and exceptional phytoremediation potential, duckweed has been successfully integrated into rice–aquatic farming systems, contributing to both yield improvement and water quality enhancement[35,36]. Notably, under nutrient-deficient conditions, duckweed exhibits phenotypic plasticity by expanding frond surface area and lengthening root structures to maximize nitrogen uptake, thereby making it an effective biological sink for Nr[36−38].

Previous research has largely examined duckweed's capacity to mitigate NH3 volatilization from rice paddies[39,40]. Specifically, duckweed has been shown to reduce NH3 emissions by up to 53.7% when co-applied with urea, achieved through lowering surface-water pH and depleting NH4+[39,41]. However, the soil nitrogen cycle operates as an interconnected network where multiple Nr are linked through interdependent pathways. This complexity means that a sole focus on NH3 overlooks potential shifts in emissions of NOx, HONO, and N2O induced by duckweed. A comprehensive evaluation across all major Nr species is therefore essential to developing truly effective mitigation strategies in paddy systems.

In this study, a dynamic chamber system was employed to quantify the effects of duckweed on fluxes of HONO, NO, NO2, N2O, and NH3 from paddy soils. This technique was validated by a previous study for reliable stimulation of reactive gas fluxes observed under field conditions[42]. Peak gas release rates were then correlated with soil physicochemical properties and abundances of key microbial functional genes. Finally, partial least squares path modeling (PLS-PM) was employed to disentangle the direct and indirect mechanistic routes through which duckweed modulates Nr emissions. These findings will provide a foundation for developing integrated strategies that improve NUE, protect ecological health, and promote the long-term sustainability of rice cultivation.

-

The experimental soil was collected from the 0–20 cm surface layer of a rice paddy located in Qingpu Modern Agricultural Park, Shanghai, China. Based on the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Soil Taxonomy, the collected soil was classified as an Orthic Entisol. After collection, the soil was air-dried and sieved through a 60-mesh sieve. Detailed physical and chemical properties of the soil are presented in Supplementary Table S1. The duckweed species used in this study was Lemna minor L. (hereafter referred to as 'Qingping'), which was cultivated in the laboratory using Hoagland nutrient solution. Following the formulation specified in Supplementary Table S2, the nutrient solution was prepared from stock solutions and diluted with deionized water, and adjusted to a pH of 6.5–7.5 using NaOH. Cultivation was carried out at 23 °C under continuous illumination. The total phosphorus (TP) and total nitrogen (TN) contents of duckweed were measured to be 1.8% and 6.1% of fresh weight, respectively.

Experimental design

-

Three treatments were designed based on the presence or absence of duckweed and nitrogen fertilizer: (1) a control with untreated paddy soil (CK); (2) a nitrogen-fertilized control (CKN); and (3) a nitrogen-fertilized treatment with duckweed addition (FS). Each treatment was conducted in triplicate. Detailed treatment information is provided in Supplementary Table S3.

For each replicate, 40 g of air-dried soil (sieved through a 2 mm mesh) was evenly spread into a 90 mm-diameter glass Petri dish. The CK group received 50 mL of ultrapure water (w:w = 1:1.25); the CKN group supplied with 50 mL of urea solution (0.040 g urea dissolved in 50 mL ultrapure water, equivalent to 180 mg·N·kg−1 soil); and the FS group was added 4 g of duckweed to the CKN treatment, ensuring full coverage of the water surface. All treatments were adjusted to reach maximum water-holding capacity (WHC). WHC was defined as the mass of water in soil at field capacity normalized by the dry soil mass, calculated as:

$ WHC=\dfrac{m_{\text{sat(water)}}}{m_{\text{dry soil}}}\text{%} $ where, msat(water) is the water mass at field capacity (kg) and mdry soil is the oven-dry soil mass (kg).

A dynamic chamber system was used to stimulate Nr gas emissions (NH3, N2O, and NOy species, including HONO, NO2, and NO) under alternating wetting–drying soil conditions with and without duckweed. In this study, NOy refers to the sum of gaseous reactive nitrogen oxides (HONO, NO2, and NO), which are key intermediates in nitrogen cycling and atmospheric deposition. The observed emission patterns (Supplementary Fig. S1) showed overlapping flux trends in NO and NOx, and synchronized peaks of HONO with NOx. Petri dishes were placed in the chambers and incubated at 25 ± 0.5 °C. The system was continuously flushed with dry zero air (free of H2O, HONO, NOx, and hydrocarbons) at a flow rate of ~6 L·min−1 until complete soil desiccation. Gas concentrations in the chamber headspace were continuously measured at a flow rate of ~1 L·min−1. During measurements, a full wetting-drying cycle was defined as the process from wetted soil to the absence of detectable water vapor in the chamber, in which the drying phase required 6–12 h.

The dynamic chamber system, which has been widely used for quantifying soil HONO emissions[23,43], consists of four subsystems: zero air generation, sample processing, gas analysis, and data acquisition. Instruments used include: a zero-air generator (Thermo, Model 1150-111); two LOPAP analyzers (QUMA Elektronik & Analytik GmbH, Germany) for HONO and NO2; a NOx analyzer (Thermo, 42i-TL, USA) for NO; a CO2/H2O analyzer (LI-COR 840A, USA); a quantum cascade laser absorption spectrometer (UMAQS) for N2O; and a cavity ring-down spectrometer (Picarro G2103, USA) for NH3. The schematic diagram of the dynamic chamber measurement system is shown in Supplementary Fig. S2.

Preliminary incubation experiments were also conducted under the same soil and treatment conditions as the main experiment to determine the appropriate sampling time for soil physicochemical and microbial analyses.

Soil physicochemical analyses

-

Soil samples were collected at five critical stages: before the onset of wetting–drying cycles (start), at peak emission times for NOy, N2O, and NH3, and at the end when soil moisture was fully depleted. These stages are abbreviated as: start, NOy, N2O, NH3, and end. The following soil properties were analyzed: (1) pH: measured in a 1:5 (w:v) soil–ultrapure water suspension. After stirring for 2 min and settling for 30 min, the pH was determined using a pH meter (PHS-3E, INESA Scientific Instrument Co., Shanghai, China); (2) Electrical conductivity (EC): measured using the same suspension and procedure as pH, with a conductivity meter (DDS-307A, INESA, China); (3) TN: measured via the Kjeldahl method. A 1.0000-g soil sample was digested with 5 mL of concentrated sulfuric acid and catalysts for 3 h, followed by distillation and titration with 2% boric acid containing a mixed indicator (methylene blue–methyl red). Instruments used included a digestion furnace (SKD-20S2) and a Kjeldahl analyzer (SKD-200, PEIO Analytical Instruments, China); (4) Inorganic nitrogen (NH4+, NO3−, NO2−): NH4+ and NO3− were extracted with 2 M KCl (2 g soil : 10 mL solution), while NO2− was extracted with deionized water. All extracts were analyzed using a continuous flow analyzer (Smart Chem 450, AMS, Italy); (5) Microbial biomass nitrogen and carbon (MBN, MBC): determined by the chloroform fumigation–extraction method and measured using a TOC/TN analyzer (Multi N/C 3000, Analytik Jena AG, Germany). All concentrations were calculated on a dry weight basis.

Quantification of nitrogen-cycling functional genes

-

Total soil DNA was extracted using the Fast DNA Spin Kit (MP Biomedicals LLC, USA). DNA quality and concentration were assessed with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, USA), and DNA integrity was verified by 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis. Gene abundance was quantified using fluorescence-based real-time PCR, with results converted to gene copy numbers per gram of dry soil. Primer sequences for each gene are listed in Supplementary Table S4. The amplification efficiency of this experiment's results exceeded 99.51%, and the standard curve slope was approximately –3.

Data processing and statistical analysis

-

The emission fluxes of Nr gases (HONO, NOx, N2O, and NH3) were calculated using the following equation[44]:

$ \mathrm{F}=\dfrac{\mathrm{Q}}{\mathrm{A}}\times \dfrac{14}{{\mathrm{V}}_{0}}\times ({\mathrm{\chi }}_{\mathrm{o}\mathrm{u}\mathrm{t}}-{\mathrm{\chi }}_{\mathrm{i}\mathrm{n}})\times \dfrac{{\mathrm{T}}_{0}}{{\mathrm{P}}_{0}}\times \dfrac{{\mathrm{P}}_{\mathrm{m}}}{{\mathrm{T}}_{\mathrm{m}}} $ where, F is the gas flux (ng·N·m−2·s−1); Q is the airflow rate (m3·s−1); A is the surface area of the soil (m2); V0 is the molar volume of air under standard conditions (m3·mol−1); χout and χin are the outlet and inlet mixing ratios of the gas (ppb), with χin = 0; Tm, Pm are the measured temperature (K) and pressure (Pa), respectively; T0, P0 are the standard temperature and pressure (273.15 K and 101,325 Pa).

The cumulative emissions of nitrogen gases during a single wetting–drying cycle were calculated as:

$ \mathrm{E}={\int }_{\mathrm{t}\mathrm{ }=\mathrm{ }0}^{\mathrm{t}\mathrm{ }=\mathrm{ }\mathrm{m}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{x}}\mathrm{F}\left(\mathrm{t}\right) \times \mathrm{d}\mathrm{t}/{10}^{6} $ where, E is the total nitrogen emission (mg·N·m−2), and F(t) is the flux at time t. Data processing was performed using Microsoft Excel (Office 2019). Figures were generated using Origin 2022 and R (version 4.1.3). One-way ANOVA and Duncan's multiple range tests were conducted using the 'agricolae' package in R (α = 0.05). PLS-PM was constructed using the 'Plspm' package to evaluate potential pathways through which duckweed influences gas emissions. The latent variables were defined as: Duckweed (treatment factor); Soil (composite of soil physicochemical indicators); Gene (composite of functional genes involved in nitrogen cycling); and Gas emissions (HONO, NOx, N2O, or NH3, depending on the model). A Mantel test was conducted using the 'ggcor' package to explore correlations between soil physiochemical properties and nitrogen gas emissions.

-

The incorporation of duckweed into paddy soil significantly reduced the emissions of NOy, particularly HONO and NOx (Fig. 1). Over the entire experimental period, duckweed intervention mitigated the accumulative emissions of HONO and NOx by 72.4% and 52.9%, respectively, compared to the CKN. As shown in Supplementary Table S5, NO emissions were consistently higher than NO2 across all treatments, with NO/NO2 ratios of 6.0 (CK), 9.0 (CKN), and 15.5 (FS). This observation aligns with previous studies, which confirm that NO is the dominant nitrogen oxide emitted from paddy soils[45−49]. The predominance of NO is likely attributed to two factors: (1) denitrification produces more NO than nitrification produces NO2 under flooded conditions[50]; and (2) NO2 may be prone to transformation into HNO3 or other nitrogen species in moist soils, while its strong adsorption affinity limits its release as a gas[51]. Although both NO and NO2 emissions were significantly lower in the FS treatment, with a reduction of 50.8% and 71.2%, respectively, compared to CKN (Supplementary Table S5), the NO/NO2 ratio increased. This suggests that duckweed may reduce oxygen diffusion and inhibit oxidation of NO to NO2, thereby suppressing NO2 formation in soil[52,53].

Figure 1.

Soil Nr fluxes change as a function of soil water content (% WHC). Soil (a) HONO, (b) NOx, (c) N2O, and (d) NH3 emissions from CK (green lines and bars), CKN (red lines and bars), and FS (blue lines and bars), respectively. The lines indicate the average results during incubation, and the shadow areas represent the standard deviations (n = 3). The right part of (a)–(d) shows the cumulative integrated Nr gas emissions from CK, CKN, and FS, respectively. Error bars represent standard errors of the means (n = 3). CK: control group; CKN: nitrogen-fertilized control; FS: nitrogen-fertilized treatments with duckweed addition. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences according to the LSD test for one-way ANOVA at p < 0.05 (n = 3).

Figure 1 shows the fluxes and peak values of gaseous emissions. For HONO, duckweed reduced the emission peak to a level comparable to that of the CK treatment (39.7% lower than CKN), with a similar timing of the emission peak. While total NOx flux and peak value were comparable between the FS and CKN treatments, the NOx emission peak occurred earlier in the CKN treatment. These results confirm that HONO and NOx emissions are coupled. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S1, the emission curves of NO and NOx overlapped completely, and HONO and NOx peaks occurred simultaneously, consistent with previous reports of their co-emission from soil[22,23,52].

In contrast, duckweed significantly increased the total emissions of N2O and NH3 (Fig. 1). Compared to the CKN treatment, the FS treatment exhibited 2.6-fold higher N2O emissions and a 143.2-fold increase in NH3 emissions. Ma et al. similarly found that duckweed reduced CH4 but elevated N2O emissions in rice paddies[54], highlighting potential ecological risks associated with enhanced greenhouse gas emissions. The likely mechanisms include: (1) the secretion of root exudates under nitrogen fertilization, which provides labile carbon to stimulate denitrification and thereby promote N2O production; and (2) abundant NH4+ in FS (Fig. 2) found in this study, which may supply substrate for nitrification and lead to N2O production[41,55].

Figure 2.

Dynamic of physical and chemical properties of the soil, including (a) pH, (b) EC, (c) TN, (d) NH4+, (e) NO2−, (f) NO3−, (g) MBN, and (h) MBC at the emission peaks of NOy, N2O, and NH3, respectively, and at the end of the measurement. Different letters denote significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05).

Notably, this finding contrasts with prior findings that duckweed suppresses NH3 volatilization[39,41,56]. This discrepancy may stem from the low initial soil pH in this study (Supplementary Table S1), where baseline NH3 emissions in CK and CKN were minimal and statistically indistinguishable. Duckweed addition increased soil pH, which is positively correlated with NH3 emissions[57,58]. During the early experimental stages (Start and NOy stages), NH4+ concentrations in FS were higher than in CKN, suggesting duckweed may directly enhance NH4+ availability and thereby promote NH3 volatilization[40,59,60]. Previous long-term studies documenting NH3 suppression by duckweed likely benefit from its sustained metabolism and interactions with extracellular enzymes and microbes[61,62]. In this short-term study, duckweed experienced desiccation and potential degradation, releasing high-nitrogen biomass that could rapidly emit NH3 under microbial activity[63,64]. This conclusion is based on indirect evidence, as no incubation experiment was conducted to isolate NH3 release from duckweed biomass alone. Future work should therefore include direct decomposition studies to quantify the contribution of duckweed residues to NH3 emissions more explicitly.

As shown in Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. S1, N2O emissions in CK and CKN treatments exhibited no distinct peaks but maintained a relatively high plateau at 100%–150% WHC. In contrast, the FS treatment displayed a sharp N2O peak within this moisture range, with a peak value 2.8-fold higher than CKN. This may result from increased bioavailable carbon and nitrogen, enhancing denitrification[65]. Similarly, the NH3 emission peak in FS was 209.2 times higher than in CKN (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Effects of duckweed on the physicochemical properties of paddy soils

-

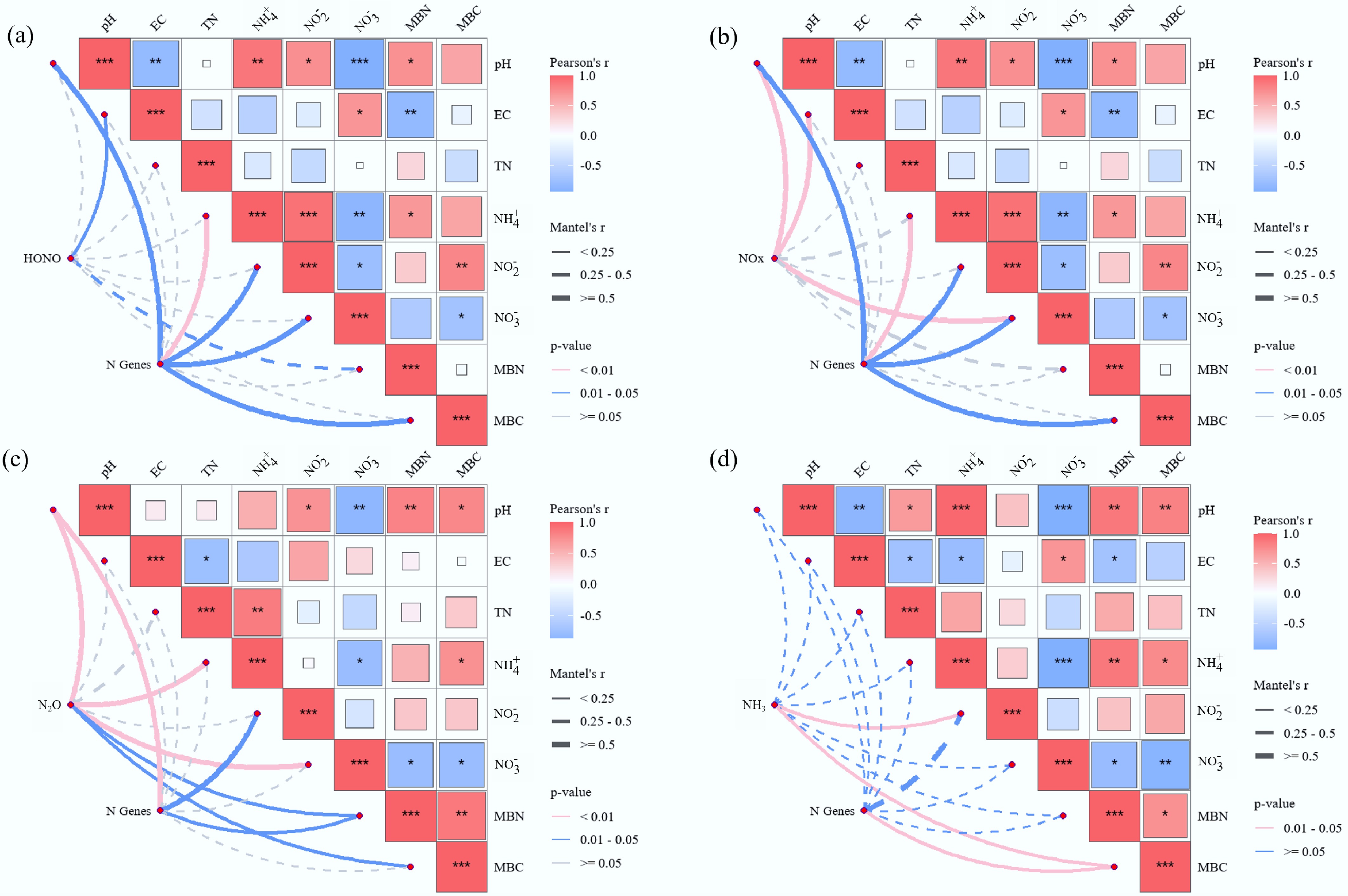

At the NOy emission peak (Fig. 2), soil pH, EC, NO2−, and MBC in the duckweed treatment (FS) were significantly higher than those in the nitrogen-only treatment (CKN). The experimental soil had an initial pH < 7; thus, duckweed introduction led to a significant pH increase and followed a significant reduction in HONO emissions. This aligns with findings by Su et al.[66], who reported that lower pH enhances NO2− protonation, thereby facilitating HONO formation. Despite the higher NO2− concentration in the FS treatment, as NO2− being a key precursor to HONO[67,68], the observed decrease in HONO emissions suggests that pH elevation had a stronger suppressive effect on HONO production than the enhancing effect of increased NO2− availability. No significant difference in EC between FS and CKN at the experiment initiation. However, during gas emission peaks and at the experiment end, EC in FS remained consistently higher than CKN, indicating that duckweed introduction increased soil EC over the experimental period. Both HONO and NOx peak fluxes showed negative correlations with EC (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. S3). Given that EC often covaries with pH[69,70], the observed EC increase may have indirectly influenced pH or affected NO2− stability in soil[22]. Additionally, high EC can induce salt stress on soil microorganisms, potentially reducing their activity and suppressing nitrogen gas emissions[71]. At the NOy emission peak, MBC in FS was significantly higher than in CKN, whereas MBN showed no significant difference. This may be attributed to increased mineral nitrogen content and a higher C:N ratio, which can reduce NUE and consequently decrease NOy emissions[72].

Figure 3.

Pearson's correlation analysis of soil environmental drivers on Nr gas emissions, (a) HONO, (b) NOx, (c) N2O, and (d) NH3. Pairwise comparisons of environmental factors are shown in squareness, with a color gradient denoting Pearson's correlation coefficient. Microbial functional genes and Nr gas emissions were related to each soil environmental factor by partial Mantel tests. Line thickness corresponds to correlation strength; color scale indicates coefficient value (blue = negative, red = positive). The asterisks indicate the statistical significance (* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001).

At the N2O emission peak, the FS exhibited significantly higher pH, EC, and NO2− levels, whereas TN and NH4+ concentrations were lower compared to CKN. MBN in FS was slightly elevated but not significantly different. The decrease in TN suggests that duckweed incorporation enhanced microbial nitrogen turnover. During this phase, as soil moisture declined, duckweed likely settled onto the soil surface and began decomposing, stimulating microbial activity. The increased bioavailable carbon and nitrogen subsequently enhanced denitrification, resulting in elevated N2O emissions[73]. The N2O peak showed a significant positive correlation with soil NO2− (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. S3). NO2− levels increased substantially at the N2O peak, concurrent with NH4+ decreased, indicating that duckweed may have promoted nitrification, accelerating NH4+ consumption and NO2− accumulation. Given that NO2− is both a nitrification product and a denitrification substrate, its accumulation supports increased N2O generation[74]. The FS treatment exhibited significantly higher N2O fluxes and peak values than CKN, together with the observed NO2− accumulation and enhanced abundance of nitrification-related functional genes (e.g., amoA) (Fig. 3). These results suggest that duckweed introduction stimulated nitrification processes, thereby contributing to elevated N2O production. The N2O peak also correlated significantly with MBN (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. S3), indicating that microbial nitrogen pools may further contribute to N2O release—consistent with prior findings[75−78].

At the NH3 emission peak, FS showed significantly lower NH4+ levels than CKN, and despite a slight elevation in soil pH, the difference was not statistically significant. The reduced NH4+ and pH in FS contrasts with the extremely high NH3 emissions, suggesting that excess NH3 volatilization may originate from duckweed itself rather than the soil during rapid wetting–drying cycling. Previous studies have reported NH3 release from duckweed tissues or residues[79]. Furthermore, duckweed is highly sensitive to NH4+ toxicity and may release large amounts of nitrogen upon rapid death and decomposition under high-nitrogen conditions[80]. Thus, despite lower soil pH and NH4+ levels, NH3 released during this phase likely derived from the duckweed biomass rather than the soil matrix.

Expression of the dynamics of nitrogen-cycling functional genes

-

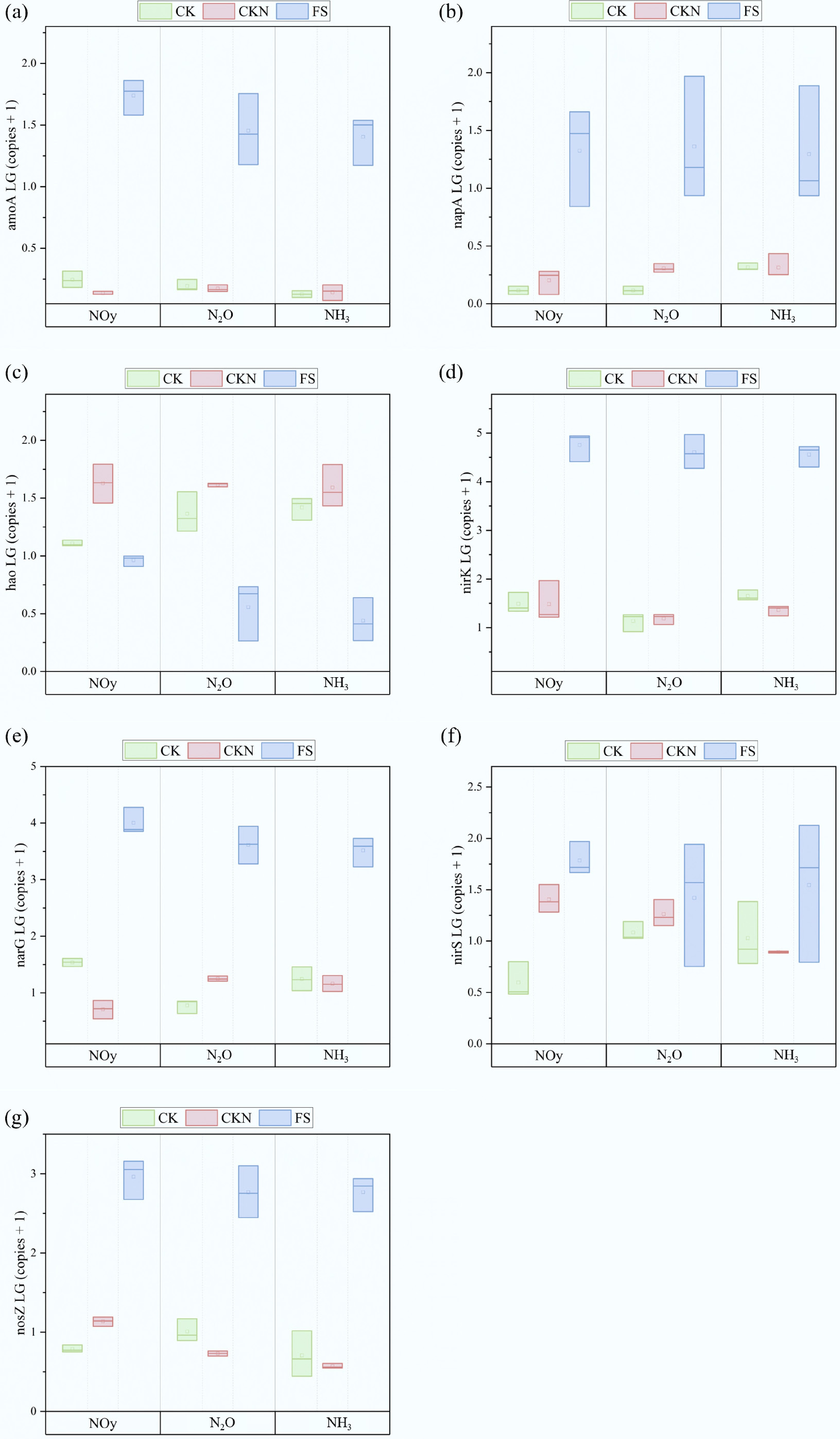

At the NO emission peak, duckweed intervention strongly stimulated the transcription of key denitrification genes. Compared with both CK and CKN treatments, FS exhibited significant upregulation of napA, nirK, narG, nirS, and nosZ, accelerating reduction of NO3− and NO2− to gaseous intermediates (Fig. 4). This phenomenon aligns with the preference of denitrifying bacteria for low-oxygen, high-moisture environments, typical of flooded paddy soils[81,82]. Additionally, elevated nirS and nosZ enhanced the conversion of NO to N2O, effectively limiting NO accumulation under the low-oxygen, high-moisture conditions characteristic of flooded paddies. This confirms duckweed's role in promoting NO-to-N2O conversion. The mechanisms by which duckweed enhanced soil N2O emissions were similar under both CK and CKN treatments. Under high soil moisture, an anaerobic environment predominated, favoring activation of NO-reducing genes such as nirK and nirS[81,82]. Furthermore, duckweed treatment significantly increased MBC, which provided heterotrophic denitrifiers with sufficient carbon sources. This further stimulated nirK and nosZ expression and enhanced the N2O production pathways[83,84].

Figure 4.

The copy numbers of functional genes, including (a) amoA, (b) napA, (c) hao, (d) nirK, (e) narG, (f) nirS, and (g) nosZ at the peak of Nr fluxes in CK, CKN, and FS groups.

Moreover, amoA expression in FS was significantly higher than in other treatments (Fig. 4), indicating that duckweed may have stimulated AOB activity and NH2OH production at this stage[85]. Conversely, hao expression was significantly downregulated, inhibiting conversion of NH2OH to N2O and NO2−[86]. The elevated pH observed in FS under alkaline conditions may have further promoted the decomposition of NH2OH and the conversion of NH4+ to NH3, contributing to increased NH3 volatilization[87]. Notably, napA expression also increased markedly in the duckweed treatment, suggesting that some microbes may have enhanced nitrate reduction through dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonia (DNRA), thus contributing to elevated NH3 emissions[88]. Furthermore, duckweed also upregulated nirK, nirS, and nosZ, indicating that N2O likely remained high during this period.

Collectively, these results indicate that duckweed intensified NO-to-N2O conversion by modulating the soil redox environment, enhancing microbial carbon supply, and promoting denitrification gene expression, leading to increased N2O emissions and underscoring potential environmental risks associated with duckweed-induced elevations in both NH3 and N2O emissions.

Multivariate path analysis and trade-offs in Nr emissions

-

To unravel the complex mechanisms by which duckweed modulates Nr emissions, multivariate statistical methods, including stepwise regression, PCA, and PLS-PM, were applied. These analyses elucidate how duckweed influences Nr emissions through direct effects and indirect pathways mediated by soil physicochemical properties and microbial functional genes. Detailed outer model loadings for latent variables in PLS-PM are provided in Supplementary Table S6.

HONO emissions

-

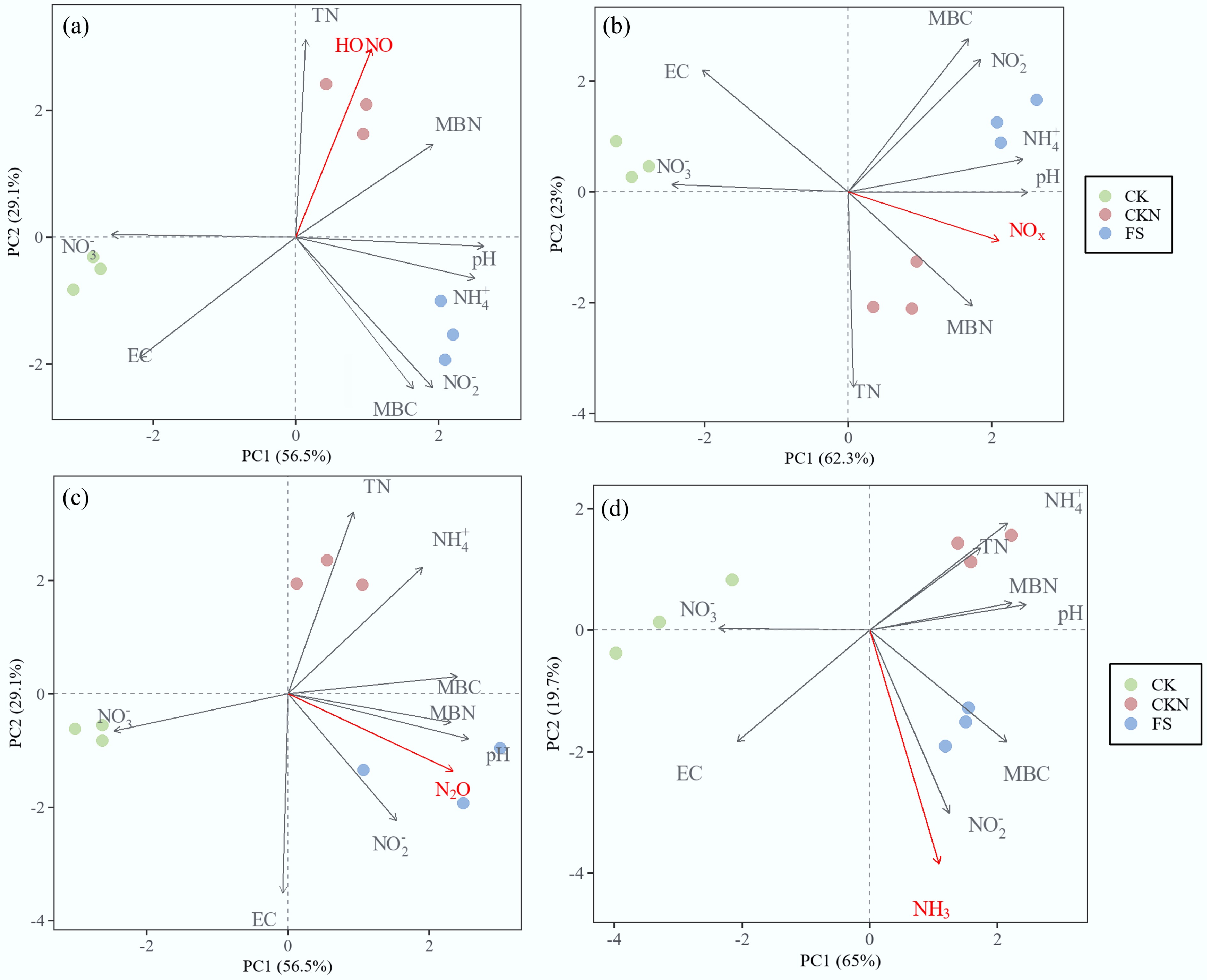

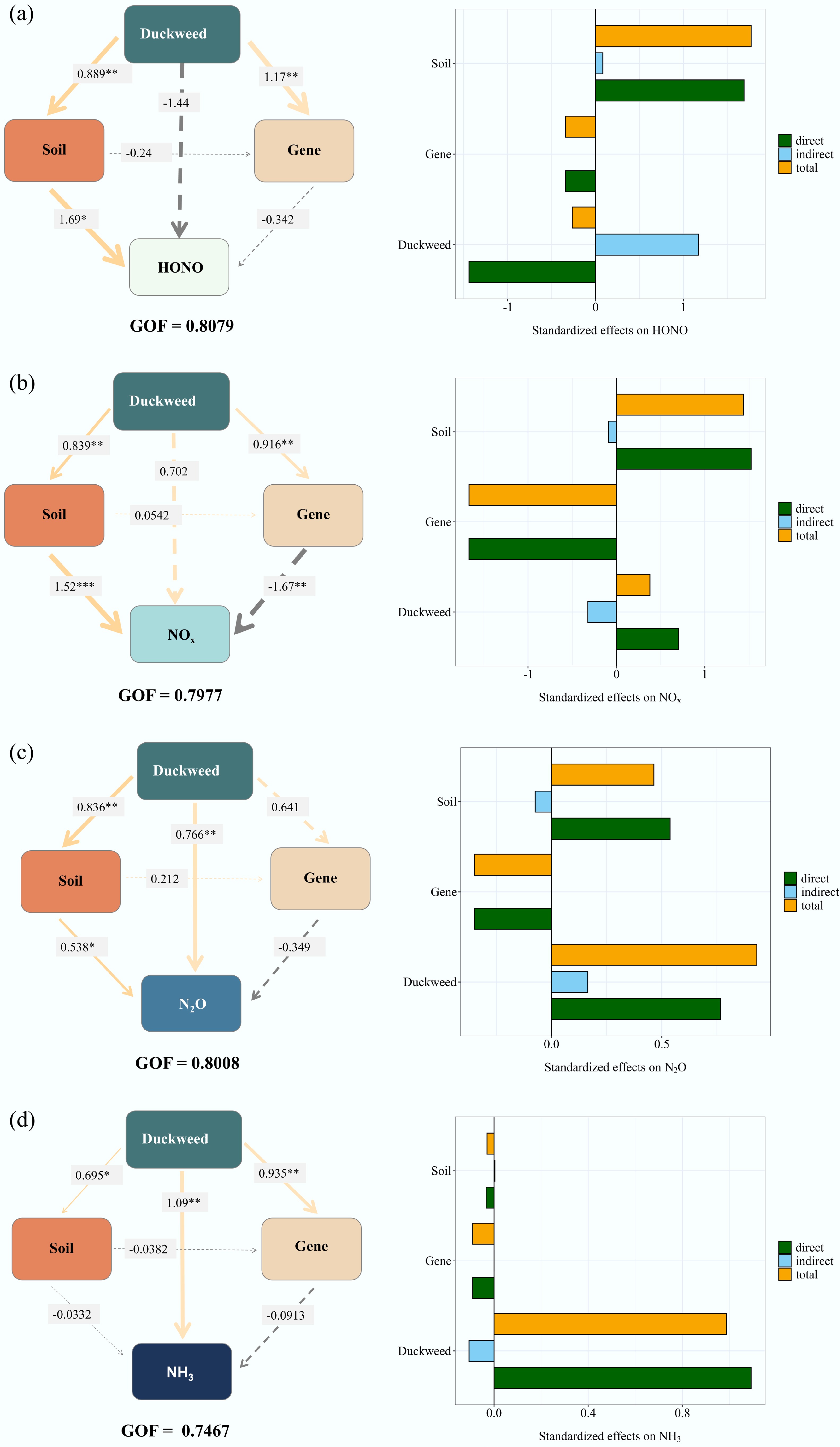

Stepwise regression identified five key soil variables—EC, NH4+, NO2−, NO3−, and MBN—as significant predictors of HONO emission peaks (Table 1). The overall model exhibited a strong robustness (R2 = 0.974), although only EC showed a statistically significant coefficient. PCA revealed that the HONO peaks were most strongly negatively correlated with EC and NO3−, while positively correlated with pH and MBN (Fig. 5a). The PLS-PM (Fig. 6a) provided a nuanced picture of duckweed's influence on HONO emissions, with a good model fit (R2 = 0.808). The model revealed a direct inhibitory effect of duckweed on HONO peaks, counterbalanced by a positive indirect effect via alterations in soil physicochemical properties. Additionally, soil nitrogen-cycling gene expression exerted a negative mediating effect on HONO emissions, which was influenced by changes in soil properties. Collectively, duckweed exhibits a direct coefficient of +1.173 on HONO emissions, offset by an indirect effect of –1.437, resulting in a net suppressive effect of –0.264 that was primarily driven by soil property modulation.

Table 1. Stepwise regression results of soil physical and chemical properties on emission peaks

Emission Predictor Estimate p-value HONO~ EC −1.21 0.0227 NH4+ −2.20 0.0982 MBN 0.317 0.441 NO2− 1.09 0.248 NO3− −0.313 0.336 NOx~ pH 3.175 0.2343 EC 1.359 0.4504 TN −0.325 0.502 NH4+ −3.156 0.2595 MBN 0.9231 0.4986 NO3− −0.8958 0.306 N2O~ pH 3.99 0.1793 EC 0.407 0.3504 NH4+ −0.801 0.2185 MBN −0.687 0.2376 NO2− −1.66 0.2347 NO3− 1.14 0.2868 TN 0.640 0.303 NH3~ pH 5.59 0.002042 EC 1.84 0.002723 NH4+ −3.48 0.005094 MBN −0.284 0.353 Model statistics are as follows. HONO ~ EC + NH4+ + MBN + NO2− + NO3−; AIC = 5.74; F(5, 3) = 22.22, p = 0.01414; R2 = 0.9737, adjusted R2 = 0.9299; NOx ~ pH + EC + TN + NH4+ + MBN + NO3−; AIC = 13.71; F(6, 2) = 6.197, p = 0.1454; R2 = 0.949, adjusted R2 = 0.7958; N2O ~ pH + EC + NH4+ + MBN + NO2− + NO3− + TN; AIC = −12.74; F(7, 1) = 65.84, p = 0.09462; R2 = 0.9978, adjusted R2 = 0.9827; NH3 ~ pH + EC + NH4+ + MBN; AIC = 11.37; F(4, 4) = 15.28, p = 0.01086; R2 = 0.9386, adjusted R2 = 0.8771.

Figure 5.

Principal component analysis (PCA) of the maximum flux of different treatments (CK, CKN, and FS) and their relationships with soil physiochemical properties at the emission peaks of: (a) HONO, (b) NOx, (c) N2O, and (d) NH3. Vector represent explanatory variables; treatment centroids show group positions in multivariate space.

Figure 6.

Partial least squares path model (PLS-PM) illustrating the direct and indirect effects of duckweed on Nr emissions, including (a) HONO, (b) NOx, (c) N2O, and (d) NH3. The goodness-of-fit (GOF) values were 0.8079, 0.7977, 0.8008, and 0.7467, respectively. The asterisks indicate the statistical significance (* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001).

NOx emissions

-

For NOx, stepwise regression selected six soil variables—pH, EC, TN, NH4+, MBN, and NO3−—with the model showing high significance (R2 = 0.949), despite the absence of statistical significance for individual predictors (Table 1). PCA showed that NOx emission peaks were most strongly negatively associated with EC, NO3−, while positively correlated with pH, NO2−, TN, MBN, and NH4+−N (Fig. 5b). The PLS-PM model (R2 = 0.798, Fig. 6b) revealed four major pathways: (1) a direct positive effect of duckweed on NOx peak emissions (+0.702); (2) a positive indirect effect mediated by soil physicochemical properties; (3) a negative indirect effect mediated via soil microbial nitrogen-cycling gene expression, which itself was modulated by soil properties; (4) a suppressive effect through duckweed-induced regulation of specific functional genes. The combined total effect of duckweed on NOx was modestly positive (+0.378), suggesting partial counterbalancing between duckweed's promotive influences and microbial regulation.

N2O emissions

-

At the peak of N2O, seven soil parameters—pH, EC, NH4+, MBN, NO2−, NO3−, and TN—were included in the stepwise regression model, which exhibited an excellent fit (R2 = 0.9978) despite the lack of significance for individual coefficients (Table 1). PCA indicated a strong negative association between N2O peaks with NO3−, with positive associations observed for pH, MBN, MBC, and NH4+−N (Fig. 5c). The PLS-PM (R2 = 0.801, Fig. 6c) demonstrated that duckweed exerted a direct enhancing effect on N2O emissions (+0.766), accompanied by a positive indirect effect through alterations in soil physicochemical properties (+0.165). A microbially mediated negative feedback was also identified, operating through changes in nitrogen-cycling gene abundance; however, this was outweighed by a positive regulatory effect on functional gene expression that promotes N2O production. The resulting net effect was strongly positive (+0.931), indicating that duckweed intensifies microbial nitrification and denitrification processes that drive N2O emissions.

NH3 emissions

-

For NH3, stepwise regression identified pH, EC, NH4+, and MBN as key predictors, with pH and EC exhibiting statistical significance (Table 1, R2 = 0.939). PCA revealed strong positive associations between NH3 emissions and EC, NO2−, MBC, and NH4+−N (Fig. 5d). The PLS-PM (R2 = 0.7467, Fig. 6d) demonstrated a dominant direct promoting effect of duckweed on NH3 emissions (+1.093), which was moderately tempered by negative indirect effects through soil physicochemical properties and microbial gene expression. The total effect remained strongly positive (+0.987), reflecting that duckweed substantially enhances NH3 volatilization, likely driven by increased soil pH and decomposition of duckweed biomass.

Trade-offs in Nr emissions

-

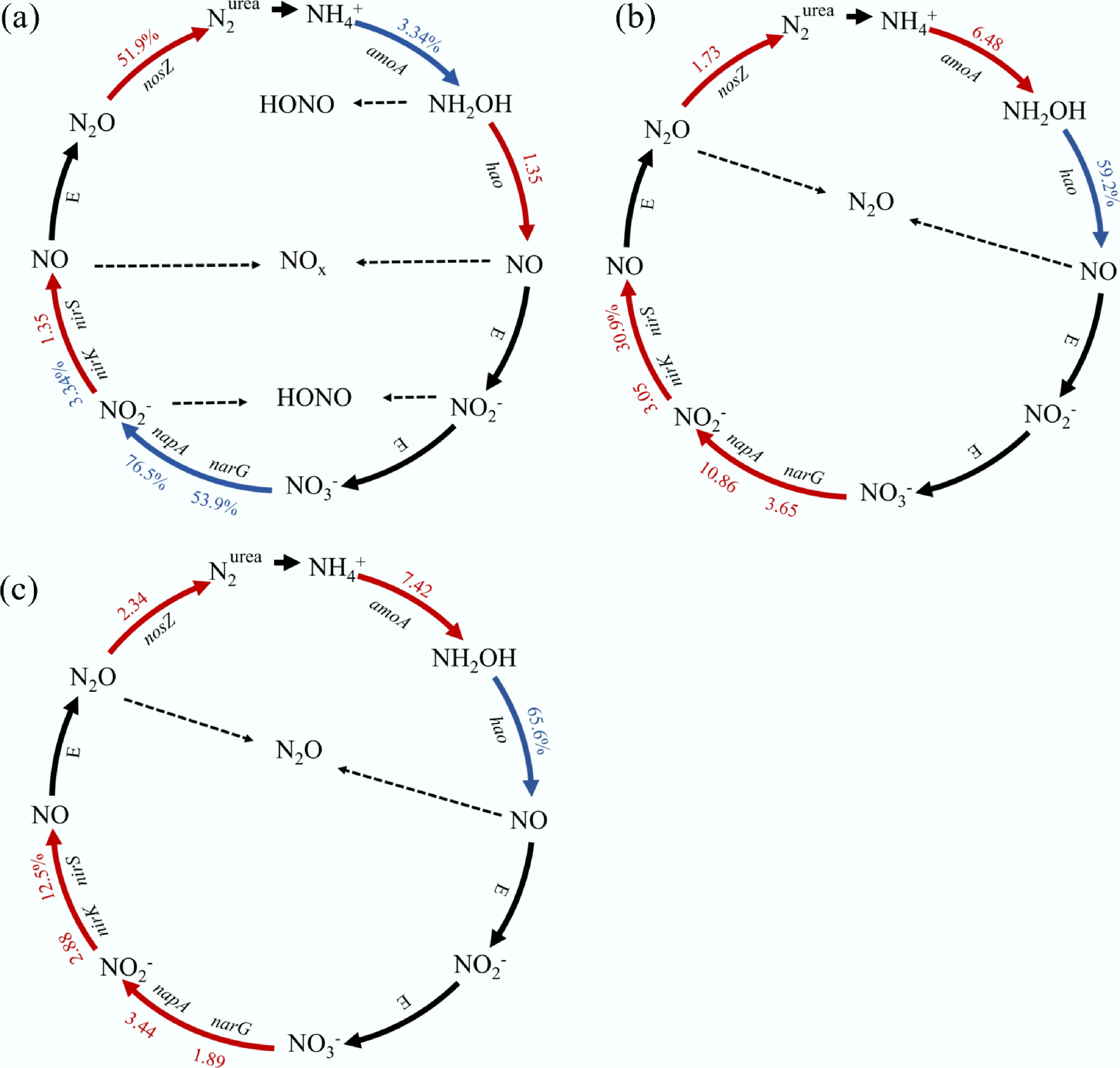

Nitrogen metabolic pathways were analyzed to clarify the differences in nitrogen cycle-related microbial gene expression between duckweed-treated and unamended soils (Fig. 7). At the HONO and NOx emission peaks (Fig. 7a), the comparison of CK and CKN revealed that nitrogen fertilizer suppressed amoA expression by 3.34%, indicating inhibition of ammonia oxidation. In contrast, hao and nirS transcripts increased by 135%, suggesting enhanced NH2OH oxidation and NO2− reduction, possesses that likely contributed to increased NOy formation. At the N2O emission peak, duckweed exerted a pronounced effect on denitrification gene expression. Compared with CK (Fig. 7b), the FS treatment significantly upregulated amoA (648%), nirS (30.9%), and nosZ (173%), indicating that duckweed stimulated the complete denitrification pathway. This trend persisted in the comparison between FS and CKN (Fig. 7c), where nirK and nosZ were significantly elevated by 288.0% and 234.0%, respectively, suggesting that duckweed promoted both NO2− reduction and N2O production. Despite the increased nosZ expression, elevated N2O emissions under FS treatment suggested incomplete denitrification due to excessive labile carbon released from decomposing duckweed biomass.

Figure 7.

The differences of N cycle functional gene transcripts between duckweed and unamended soil, including (a) differences between CK and CKN at the HONO and NOx peak, (b) differences between CK and FS at the N2O peak, and (c) differences between CKN and FS at the N2O peak.

Collectively, duckweed reshaped nitrogen metabolic pathways by modulating key microbial functional gene expression and soil physicochemical properties. This multivariate path analysis reveals a complex trade-off driven by duckweed: while effectively suppressing HONO and NOx emissions (thereby potentially reducing nitrogen oxide pollution), it simultaneously promotes N2O and NH3 emissions. These latter gases have significant implications for greenhouse gas effects (N2O)[89] and atmospheric nitrogen deposition (NH3)[90]. Duckweed's dual role was reflected in its capacity to suppress HONO and NOx emissions while increasing N2O and NH3 release driven by residue decomposition and associated shifts in soil physicochemical properties and microbial activity. These contrasting effects highlight that simple duckweed introduction is insufficient; rather, balanced management strategies are required to maximize its benefits for NOy mitigation while minimizing unintended risks of elevated greenhouse gas and ammonia emissions. For example, periodic duckweed harvesting has been shown to effectively remove nitrogen and phosphorus biomass before decomposition, thereby reducing secondary NH3 emission risk while enabling utilization as animal feed or bioenergy feedstock[91,92]. In addition, combining duckweed application with soil amendments (e.g., biochar or nitrification inhibitors) may mitigate N2O and NH3 losses by improving soil pH buffering, enhancing sorption capacity, and suppressing nitrification[91,93,94].

Agricultural and environmental implications

-

From an agricultural perspective, duckweed's capacity to significantly reduce emissions of NOy—particularly HONO and NOx—holds substantial promise. These gases are primary contributors to atmospheric Nr deposition, which can induce ecosystem eutrophication and air quality deterioration[95,96]. By suppressing NOy emissions by over 50%, duckweed may help mitigate downstream consequences such as soil acidification[97], nutrient imbalances[98], and deleterious nitrogen deposition in adjacent terrestrial and aquatic systems[99,100]. Duckweed's surface coverage modifies soil redox conditions and oxygen diffusion, creating a microenvironment less conductive to NO and HONO production. This effect aligns with sustainable agricultural objectives by potentially reducing the environmental footprint of rice production without compromising soil health.

However, this benefit is counterbalanced by the observed increases in N2O and NH3 emissions. The elevated N2O emissions, more than doubling in the presence of duckweed, raise concerns given N2O's status as a potent greenhouse gas with a global warming potential approximately 300 times that of CO2[8,101]. This suggests that duckweed incorporation, while reducing certain Nr losses, may inadvertently exacerbate greenhouse gas emissions from paddy fields. The underlying mechanism appears linked to enhanced microbial nitrification and denitrification processes fueled by labile carbon released from duckweed biomass decomposition[102,103]. This indicates that nitrogen management in duckweed-covered systems must carefully regulate carbon inputs and soil moisture dynamics to prevent unintended environmental impacts.

The drastic increase in NH3 emissions also carries significant implications, as NH3 contributes to atmospheric nitrogen deposition and can indirectly induce soil acidification and eutrophication[104,105]. The results suggest that a substantial portion of this NH3 may originate from the rapid degradation of duckweed biomass under alternating wet–dry conditions, which releases nitrogen-rich compounds into the atmosphere. This highlights the importance of accounting for the temporal dynamics of duckweed growth, decay, and nitrogen release when designing rice–aquatic integrated systems. As indicated in prior studies[57,98,106], long-term or continuous duckweed coverage with steady biomass turnover might moderate this effect; however, rapid biomass cycling appears to pose risks of elevated NH3 losses.

For agricultural management, these findings underscore the necessity of a balanced approach when incorporating duckweed into rice paddies. While duckweed provides a natural, cost-effective means to suppress NOy emissions and improve NUE through its high nitrogen uptake capacity, its potential to increase N2O and NH3 emissions necessitates complementary strategies. These could include optimizing irrigation or rotation regimes[32,107], regulating soil pH and EC[98,108], and integrating nitrification inhibitors or biochar amendments to mitigate greenhouse gas production[32,109]. Monitoring soil microbial communities and functional gene expression may also provide indicators for adaptive management. However, these experiments were conducted under controlled laboratory incubation conditions, which cannot fully capture the dynamic processes and environmental variability of field rice paddies. Therefore, these findings should be interpreted primarily as mechanistic insights into how duckweed modulates Nr emissions. Future work should focus on long-term field trials to validate these results under realistic agronomic conditions and to develop optimized duckweed-based management strategies.

From an environmental perspective, duckweed's dual role highlights the complexity of biological mitigation strategies in agroecosystems. Its capacity to simultaneously modulate multiple nitrogen pathways emphasizes the need for integrated, system-level assessments rather than a narrow focus on individual gas emissions. Future research should prioritize long-term field-scale studies and explore how combined mitigation approaches can maximize environmental benefits while minimizing trade-offs. For policymakers and practitioners, implementing duckweed-based interventions for nitrogen management in paddy agriculture requires a thorough evaluation of these trade-offs and consideration of site-specific conditions.

-

This study reveals that duckweed significantly modulates nitrogen cycling in paddy soils by reducing emissions of NOy gases (HONO and NOx) through modifications to soil redox conditions and microbial processes. However, duckweed enhances N2O and NH3 emissions, driven by intensified microbial nitrification and denitrification processes fueled by duckweed biomass decomposition. PLS-PM modeling showed that duckweed influences Nr emissions through both direct effects and indirect pathways mediated by soil properties and microbial gene expression, highlighting the complex plant-soil-microbe interactions regulating N transformations. While duckweed presents a promising strategy for mitigating NOy emissions and improving nitrogen retention, the concurrent increase in N2O and NH3 emissions underscores the necessity of integrated management to balance these trade-offs. Optimizing duckweed utilization could enhance sustainable nitrogen cycling and reduce environmental impacts in rice production systems.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/nc-0025-0008.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Lan Y, Xu S, Sha Z; data collection: Lan Y, Xu S; analysis and interpretation of results: Liu X, Li D; draft manuscript preparation: Lan Y, Chu Q; methodology: Wu D, Xu Y; figure visualization: Liu X, Li D; supervision and funding acquisition: Sha Z; writing – review and editing: He P, Chen C. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The data supporting the findings of this study are not publicly available due to institutional or regulatory restrictions.

-

This work was supported by the Agricultural Research System of Shanghai, China (Grant No. 202203) and 2025 Shanghai Municipal Grassroots Science Popularization Action Plan Project (JCKP2025-29), Shanghai Qingpu Regenerative Agriculture Science and Technology Field Station.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Duckweed reduced harmful nitrogen oxide (NOy) emissions in paddy soils by over 50%.

Duckweed increased N2O and NH3 by more than two fold and 100-fold, respectively.

Duckweed changed soil conditions like pH and moisture to limit nitrogen oxide production.

Results reveal a trade-off: applying duckweed may reduce nitrogen oxide pollution but lead to higher climate and ammonia risks.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Supplementary Table S1 Physical and chemical properties of the soil in Qingpu Modern Agricultural Park.

- Supplementary Table S2 Preparation for Hoagland stock solutions and culture media.

- Supplementary Table S3 Dynamic chamber system experiment design.

- Supplementary Table S4 The primers used in the PCR amplifications.

- Supplementary Table S5 The integrated Nr gas emissions (mg·m−2) from soil in CK, CKN and FS treatments.

- Supplementary Table S6 Outer model loadings of latent variables in partial least squares path model (PLS-PM), including (a) HONO, (b) NOx, (c) N2O, and (d) NH3.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Soil Nr (HONO, NOx, NO, NO2) fluxes in the FS treatment group.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 The schematic diagram of the dynamic chamber measurement system. The diagram was adapted from Deng[1].

- Supplementary Fig. S3 The correlation of soil Nr fluxes and corresponding physical and chemical properties of the soil at the peak of (a) HONO; (b) NOx; (c) N2O and (d) NH3.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Lan Y, Xu S, Liu X, Li D, Chu Q, et al. 2025. Mechanistic evaluation of duckweed intervention on reactive nitrogen gas fluxes from paddy soils. Nitrogen Cycling 1: e008 doi: 10.48130/nc-0025-0008

Mechanistic evaluation of duckweed intervention on reactive nitrogen gas fluxes from paddy soils

- Received: 29 July 2025

- Revised: 15 September 2025

- Accepted: 25 September 2025

- Published online: 28 October 2025

Abstract: Paddy soils represent significant sources of reactive nitrogen (Nr) gases, which exert a critical impact on environmental sustainability and the global nitrogen cycle. To explore nature-based alternatives for nitrogen management, this study assessed the effects of duckweed (Lemna minor L.) introduction on emissions of HONO, NO, NO2, N2O, and NH3 from paddy soils. Using a dynamic chamber system, Nr gas fluxes were continuously monitored under three treatments—control (CK), nitrogen-fertilized soil (CKN), and fertilized soil with duckweed (FS)—throughout a complete wetting–drying cycle, from maximum water-holding capacity (WHC) to full desiccation. Duckweed notably suppressed cumulative HONO and NOx emissions by 72.4% and 52.9%, respectively, primarily through alterations in soil redox status, elevated pH and electrical conductivity, and increased expression of microbial denitrification genes. However, duckweed incorporation significantly elevated emissions of N2O by 2.6-fold and NH3 by 143.2-fold compared to CKN. This enhancement resulted from duckweed residue decomposition, which provided unstable carbon sources, enhanced accumulation of nitrification and denitrification intermediates, and promoted conversion of NH4+ to NH3 under elevated pH conditions. Partial least squares path modeling (PLS-PM) clarified that duckweed affects Nr gas emissions through both direct actions and indirect influences mediated by soil physicochemical characteristics and microbial functional gene expression. This study provides a comprehensive mechanistic evaluation of duckweed's dual role in rice paddy ecosystems: mitigating nitrogen oxides emissions while exacerbating ammonia and greenhouse gas releases. The findings highlight critical trade-offs in applying duckweed for sustainable nitrogen management, emphasizing the need for a cautious, integrated approach to optimize ecological benefits and minimize environmental risks. Future work will focus on long-term field-scale studies to develop refined duckweed management strategies that balance these trade-offs and enhance sustainable nitrogen cycling in rice-paddy agroecosystems.