-

Staircase evacuation is the most traditional method employed in most buildings. However, as urbanization progresses and the economy and population of cities grow, the number and scale of high-rise buildings are expanding. In emergencies, depending solely on staircases for evacuation may lead to significant fatigue among evacuees, particularly in tall buildings; they could also slow down the flow of people by becoming bottlenecks[1]. Additionally, there is a high risk of crowding on staircases, which can further hinder evacuation. Staircase evacuation is particularly inefficient for vulnerable groups such as the elderly and individuals with illnesses, disabilities, or limited mobility. Therefore, it is reasonable to consider using elevators as a supplementary evacuation method to enhance overall evacuation efficiency.

In recent years, high-rise building fires have become frequent globally, resulting in severe casualties. For instance, on November 15, 2010, a major fire broke out in a 28-story apartment building in the Jing'an District of Shanghai, rapidly engulfing the entire structure in flames. The incident resulted in 70 injuries and 58 fatalities. Similarly, on June 14, 2017, a fire consumed the 24-story Grenfell Tower in London, UK, leading to 79 deaths due to delayed evacuation efforts. A tragic fire occurred on December 21, 2017[2], at an eight-story sports complex in Jecheon, Chungcheongbuk-do, South Korea, killing 29 people and injuring many others. On October 14, 2021[3], a fire in the 'City in a City' building in Kaohsiung City, Taiwan, China, caused a 12-story structure to burn down, resulting in 46 deaths and 41 injuries[4]. Given such incidents, there is a growing interest in developing strategies for safely and effectively evacuating many people from high-rise buildings. In emergencies, the primary objective is to evacuate occupants to a safe location swiftly and efficiently using the most appropriate evacuation techniques.

Elevator-assisted evacuation (EAE) refers to elevators as an additional means of egress during fire emergencies[5−7]. Several experts have advocated for using elevators to help evacuate individuals with mobility impairments during high-rise building fires, aiming to enhance overall evacuation efficiency[8,9]. This approach can assist occupants who struggle with stair evacuation by providing a nearby elevator as a viable alternative. Over the past few decades, numerous studies have examined the advantages of incorporating elevators into evacuation plans[10−12]. With advancements in modern technology, both domestic and international scholars have investigated various challenges associated with high-rise building evacuation. A significant portion of this research has focused on fire scenarios in high-rise buildings, assessing the feasibility and safety of using elevator-assisted evacuation amidst fire and smoke spread[13−18].

The International Code Council's Building and Fire Codes[19] and the National Fire Protection Association's Building and Fire Codes[20] already allow evacuees to use elevators for evacuation in case of fire and other emergencies. Nevertheless, elevators are rarely used for evacuation in high-rise structures. However, elevators have been used in several documented occurrences[21−23]. This demonstrates that elevators are feasible to aid in evacuation in tall buildings.

However, concerning elevator-assisted evacuation in high-rise buildings beyond the fire safety concerns mentioned earlier, evacuation efficiency is an equally challenging issue that demands careful consideration[24]. Scholars have developed various evacuation models to enhance the efficiency of elevator-assisted evacuation in such scenarios. For example, Yan et al.[25] used Pathfinder software and found that effective use of stairs, elevators, and refuge floors, based on the distribution of people can significantly improve the efficiency of evacuation. Yan et al.[26] also found that a combination of time staggering and rational allocation of evacuation routes can significantly improve evacuation efficiency. Fang et al.[24] proposed an intelligent elevator-assisted fire evacuation scheme that identifies safer evacuation strategies based on real-time fire information and evacuation progress. Aleksandrov et al.[27] introduced a mathematical model using the Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) method to determine the optimal evacuation strategy for high-rise buildings. Ma[28] developed a model for elevator-assisted evacuation in super-high-rise buildings, demonstrating that using elevators to evacuate a suitable proportion of occupants can significantly improve overall evacuation efficiency. Kinsey et al.[29] described an intelligent body-based elevator evacuation model, analyzing the comparative advantages of using an elevator scheduling strategy involving 32 elevators and multiple exits for evacuating all building occupants. Mossberg et al.[30] proposed a design strategy, based on the theory of human behavior and availability theory, that allows designers to consider the information needs of evacuees when designing information and guidance measures for evacuation elevators. Huang et al.[31] proposed an improved cellular automata (CA) model that accounts for the effects of evacuees' rest on refuge floors and preference for taking evacuation elevators. Gao et al.[32] proposed a double-triangular access design for the coordinated use of elevators and staircases, which solves the key problem of evacuation in high-rise buildings and minimizes the economic losses associated with the use of space for evacuation routes. The findings from these studies confirm that with well-planned evacuation strategies, elevator-assisted evacuation is a viable option. Existing high-rise building evacuation strategies remain overly reliant on traditional stair-based methods. Stairs serve as the dominant evacuation path, with elevators typically reserved for the disabled and elderly, or treated merely as a backup option. This approach overlooks the potential value of elevators and inadequately quantifies their role in upward/downward evacuation. Furthermore, existing elevator evacuation strategies often lack clear allocation rules, such as defining building-wide availability. Crucially, if occupants on every floor are permitted to use elevators simultaneously, evacuation efficiency may be reduced and elevator waiting times increased[33,34]. Additionally, in cases where accidents occur in underground sections or lower levels of above-ground buildings requiring upward evacuation, the impact of physical fatigue on evacuees can be significant. Thus, the effects of staircase-only evacuation are likely to be more pronounced in upward evacuation scenarios compared to downward evacuation[35]. However, previous elevator-assisted studies have focused on a single evacuation direction and lacked a systematic comparative analysis of upward and downward evacuation efficiency. Therefore, determining the optimal elevator-assisted evacuation strategy based on specific conditions is crucial.

In light of the above issues, this study integrates the design of refuge floors in high-rise buildings with computer modeling and simulation to investigate the coordinated evacuation dynamics of staircases and elevators during fires and other emergencies. The research examines the impact of elevator-assisted evacuation strategies under different accident scenarios on personnel evacuation efficiency. It compares upward and downward evacuation efficiency using varying elevator-assisted strategies and proposes an optimized design method for elevator-assisted evacuation strategies. The goal is to identify the synergistic effects of different elevator-assisted evacuation strategies on personnel evacuation efficiency and to develop targeted evacuation plans accordingly. The results of this study aim to provide a theoretical reference for the future application of elevator-assisted evacuation in high-rise buildings.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. The research method details the methodology and defines the relevant model parameters. Subsequently, results and discussion analyzes the effects of using elevators on upward and downward evacuation across different floors and varying proportions of evacuees. Following this, the practical application of elevator-assisted evacuation in high-rise buildings is explored, offering new insights into the cooperative strategy involving both elevators and staircases. Finally, the conclusion summarizes the key findings of this study.

-

The social force model is a mathematical framework used to simulate and analyze crowd evacuation behavior. It aims to explain the mechanical mechanisms of interactions between individuals in a group, particularly in densely populated environments such as building evacuations and subway stations. Helbing et al.[36] proposed the social force model in 1995, which abstracts pedestrians as particles that satisfy the laws of mechanical motion and are subjected to the self-driven force

$f_i^0(t)$ ${f_{ij}}$ $ {f_{iw}} $ $\varepsilon $ $ {m_i}(d{v_i}/dt) = {m_i}[v_i^0(t)e_t^0(t) - {v_i}(t)/{\tau _i}] + \sum {_{j \ne i}} {f_{ij}} + \sum {_w} {f_{iw}} + \varepsilon $ (1) Equation (1)

${m_i}$ ${v_i}$ $v_i^0(t)$ $e_t^0(t)$ ${v_i}(t)$ $i$ $t$ ${\tau _i}$ ${f_{ij}}$ $ {f_i}_j = {A_i}exp[(|{r_i}_j - {d_i}_j|)/{B_i}]{n_i}_j + kg({r_i}_j - {d_i}_j){n_i}_j + \kappa g({r_i}_j - {d_i}_j)\Delta v_{ji}^t{t_{ij}} $ (2) Where,

$ {A_i}exp[(|{r_i}_j - {d_i}_j|)/{B_i} $ $i$ $j$ ${d_{ij}}$ $i$ $j$ ${r_{ij}}$ $ kg({r_i}_j - {d_i}_j){n_i}_j $ $ \kappa g({r_i}_j - {d_i}_j)\Delta v_{ji}^t{t_{ij}} $ ${A_i}$ ${B_i}$ $k$ $\kappa $ ${f_{iw}}$ ${f_i}_j$ $ {f_{iw}} = {A_i}\exp \left[ {\left( {\left| {{r_{ij}} - {d_{ij}}} \right|} \right)/{B_i}} \right]{n_i}_j + kg({r_i}_{} - {d_i}_w){n_i}_w + \kappa g({r_i}_j - {d_i}_w)\left( {{v_i} \cdot {t_{iw}}} \right){t_{iw}} $ (3) $\varepsilon $ MassMotion is a simulation software developed based on the social force model. The reliability of MassMotion for evacuation simulations has been validated by researchers such as Marzouk et al., and Cuesta et al.[37−39], providing robust support for its application in evacuation studies. The software utilizes the social force model algorithm to simulate the dynamic interactions of individuals, allowing for the accurate tracking of their trajectories during evacuation scenarios. Scholars have previously utilized MassMotion to investigate crowd evacuation behaviors and patterns in various settings. For instance, Zhou[40] conducted experiments and simulations of staircase evacuation using MassMotion to examine the behavioral characteristics and evacuation efficiency of individuals under two distinct evacuation modes: queued evacuation and random evacuation in unidirectional staircases. Similarly, Yang et al.[41] applied the social force model as the theoretical basis for their simulations in MassMotion, studying crowd flow in commercial spaces to identify and quantify issues affecting evacuation in these environments. Additionally, Jia et al.[42] used MassMotion to construct an evacuation model that simulated the distribution of children in staircases of different sizes. They explored the relationship between staircase dimensions in kindergartens and children's evacuation efficiency through orthogonal experimental methods. In high-rise building evacuation scenarios, Zhai[43] employed MassMotion to investigate the distinction between total evacuation and phased evacuation strategies in high-rise office buildings, providing decision-makers with guidance on determining permissible occupant evacuation strategies. Yang et al.[44] utilised MassMotion and PyroSim to simulate evacuation conditions during high-rise dormitory fires, assessing fire hazards within buildings and formulating evacuation recommendations. Li et al.[45] employed MassMotion to investigate how varying proportions of incapacitated elderly residents distributed across high-rise nursing homes impact evacuation efficiency. Given the demonstrated efficacy of MassMotion in these prior studies, to facilitate the modeling process and ensure the generalizability of this study, the widely recognized software MassMotion was employed to develop a dynamic evolution model for evacuating high-rise buildings.

Basic parameter setting

-

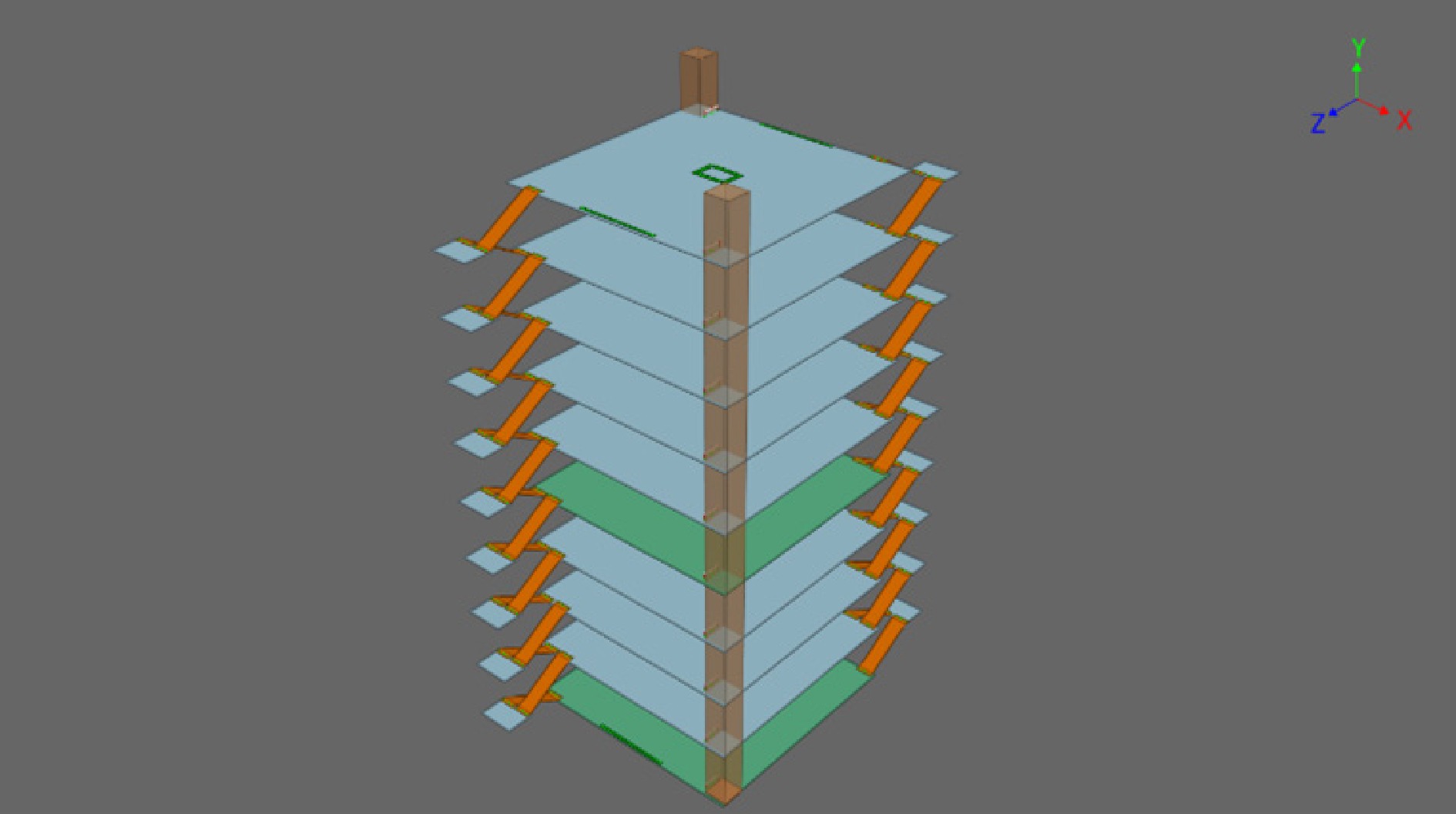

High-rise buildings face significant challenges during emergency evacuations due to their multiple floors and large vertical distances. In this study, a 10-story building with a moderate vertical height and number of floors is modeled as a standard unit for analysis. Additionally, two fire elevators and two fire staircases are incorporated to help share the evacuation load, aiming to alleviate congestion and chaos during evacuation. To simplify the research variables and more accurately explore the characteristics of cooperative evacuation efficiency in both upward and downward directions, the evacuation population is assumed to consist of young and middle-aged pedestrians.

In the model, staircase related parameters are set according to GB 50016-2014 Code for Fire Protection Design of Buildings, with a staircase width of 1.8 m and height of 2.5 m. Referring to T/CEA 0067-2024 Elevators for Assisted Evacuation of Personnel in Fires, the rated load capacity of the evacuation elevator must not be less than 800 kg. Based on this requirement and existing elevator models, the elevator is configured to carry 12 persons per trip. The remaining elevator parameters follow GB/T 7588.1-2020 Safety Rules for the Construction and Installation of Elevators, with a door width of 1.5 m, a maximum car speed of 5 m/s, and an acceleration of 2 m/s2. The floor height of the building is about 5 m, and the total height is about 50 m. The floor plan of the building is shown in Fig. 1. The speed distribution of the people follows a normal distribution: the minimum speed is 0.65 m/s, the maximum is 2.05 m/s, and the default pedestrians tend to lean to the right in the movement. The definitional properties of elevator kinematics and physical characteristics are based on the guidelines for Using Elevators in Fires[20].

During the evacuation of a high-rise building, pedestrians on different floors face varying challenges and risks. In particular, pedestrians on floors farther from the safety exits are at greater risk and encounter more difficulties during an emergency evacuation. These individuals must travel longer vertical distances to reach a safe area, which increases the likelihood of panic, anxiety, and fatigue, ultimately reducing evacuation efficiency and safety. Moreover, according to Ding et al.[46], when pedestrians evacuate to the safety exit on the ground floor, the total evacuation time saved by evacuating from higher floors to lower floors in a priority sequence is less than the time saved by evacuating from lower floors to higher floors in the same sequence. Based on these observations, this study focuses on using elevator-assisted evacuation, beginning from the floor farthest from the safety exit. The evacuation of all personnel across different floors using elevators is modeled. By varying the number of floors served by elevators, this study examines the relationship between evacuation time and elevator use, providing insights into its impact on upward and downward evacuation efficiency.

-

The efficiency of upward evacuation for pedestrians from floors 1 to 10 using stairs and elevators in concert was initially explored. In this scenario, the safety exit was set on the 10th floor, with 100 individuals assigned to each floor from the 1st to the 10th floor (corresponding to scenario u1). Subsequently, the efficiency of coordinated evacuation using stairs and elevators for downward evacuation from the 10th floor to the 1st floor was analyzed, with the evacuation exit set on the 1st floor and 100 occupants placed on each floor from the 1st to the 10th floor (corresponding to scenario d1).

At the same time, using the number of people in the building as a variable, 80 and 60 people were set on each floor from the 1st to the 10th floors, corresponding to scenarios u2–u3 and d2–d3, respectively. By adjusting the number of evacuees on each floor, the effect of the change in the number of people on the study results was compared. To show the working condition settings for the upward and downward evacuation tests more clearly, they are listed in Table 1, respectively. Lowercase u and d denote the different scenarios corresponding to changes in the number of people, and uppercase U and D represent the scenarios corresponding to the use of elevators on different floors.

Table 1. Simulation scenarios for the use of elevators on different floors during upward and downward evacuation.

No. Upward scenario (Un) Downward scenario (Dn) Staircase evacuation floor Elevator evacuation floor Staircase evacuation floor Elevator evacuation floor 1 1–9 floor − 2–10 floor − 2 2–9 floor 1 floor 2–9 floor 10 floor 3 3–9 floor 1–2 floor 2–8 floor 9–10 floor 4 4–9 floor 1–3 floor 2–7 floor 8–10 floor 5 5–9 floor 1–4 floor 2–6 floor 7–10 floor 6 6–9 floor 1–5 floor 2–5 floor 6–10 floor 7 7–9 floor 1–6 floor 2–4 floor 5–10 floor 8 8–9 floor 1–7 floor 2–3 floor 4–10 floor 9 9 floor 1–8 floor 2 floor 3–10 floor 10 − 1–9 floor − 2–10 floor To ensure the accuracy and reliability of the results, each set of scenarios was simulated ten times, incorporating various random patterns wherever possible. It is essential to highlight that this study focuses on the cooperative evacuation of stairs and elevators. Consequently, the building model has been appropriately simplified to emphasize the setup and layout of stairs and elevators, excluding accidental hazardous conditions. Based on this simplification, elevator-assisted evacuation is considered successful if the coordinated evacuation time for stairs and elevators under identical working conditions is shorter than the evacuation time using stairs alone. The simulation results, including evacuation times for each scenario, are summarized in Table 2, while the comparative analyses of upward and downward evacuation times are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Table 2. Statistics on the results of assisted evacuation using elevators for upward and downward movement.

Scheme 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 u1/s 480 424 472 801 1,055 1,531 1,947 2,307 2,915 3,344 Optimization rate − 11.7% 1.7% − − − − − − − u2/s 431 370 386 634 858 1,149 1,573 1,856 2,257 2,685 Optimization rate − 14.2% 10.4% − − − − − − − u3/s 417 316 373 499 684 876 1,115 1,422 1,705 2,027 Optimization rate − 24.2% 10.6% − − − − − − − d1/s 426 390 425 761 1,130 1,409 1,844 2,211 2,805 3,331 Optimization rate − 8.4% 0.2% − − − − − − − d2/s 385 332 363 597 875 1,131 1,487 1,806 2,255 2,680 Optimization rate − 13.8% 5.7% − − − − − − − d3/s 346 286 311 484 662 885 1,109 1,396 1,700 2,003 Optimization rate − 17.3% 10.1% − − − − − − −

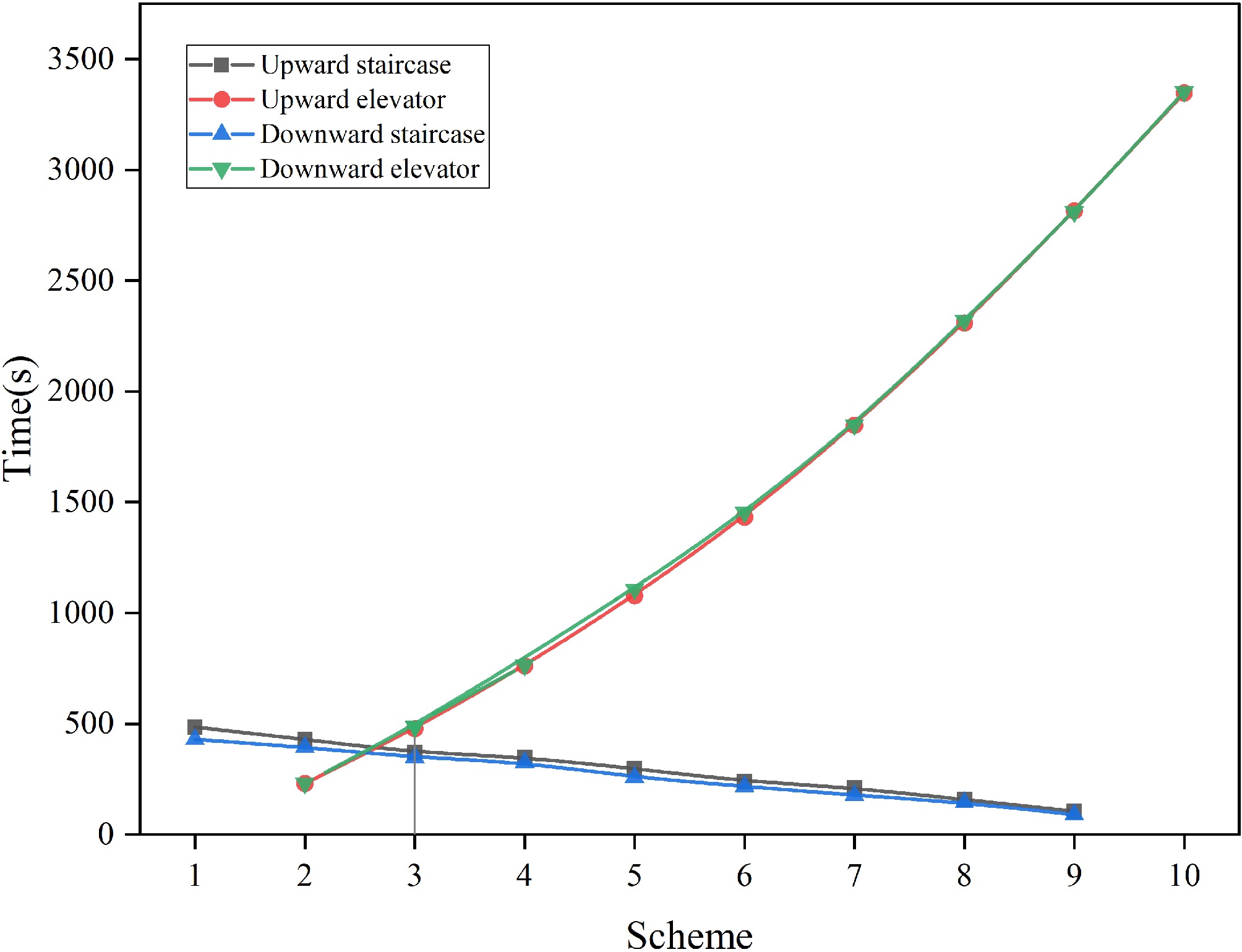

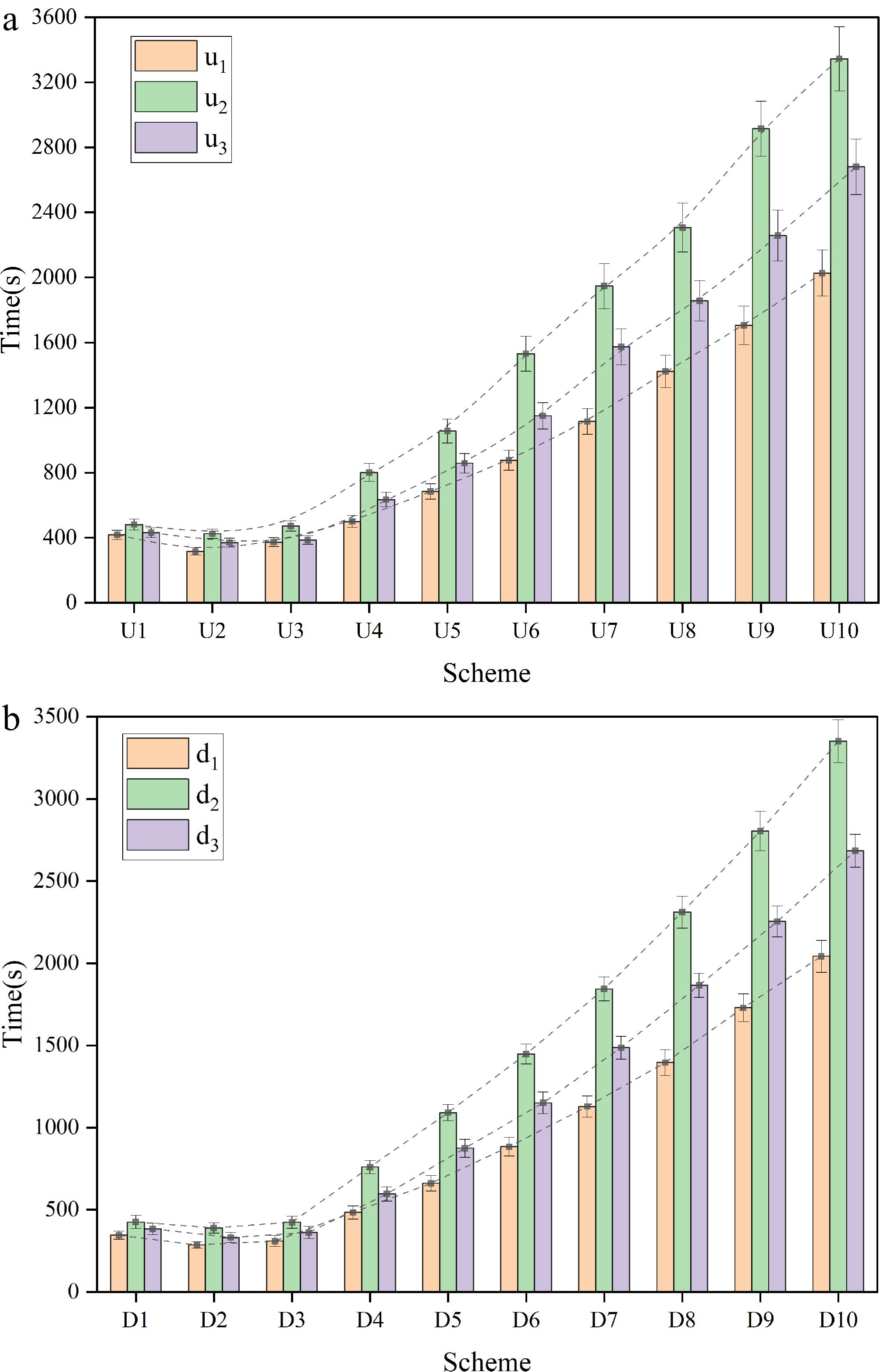

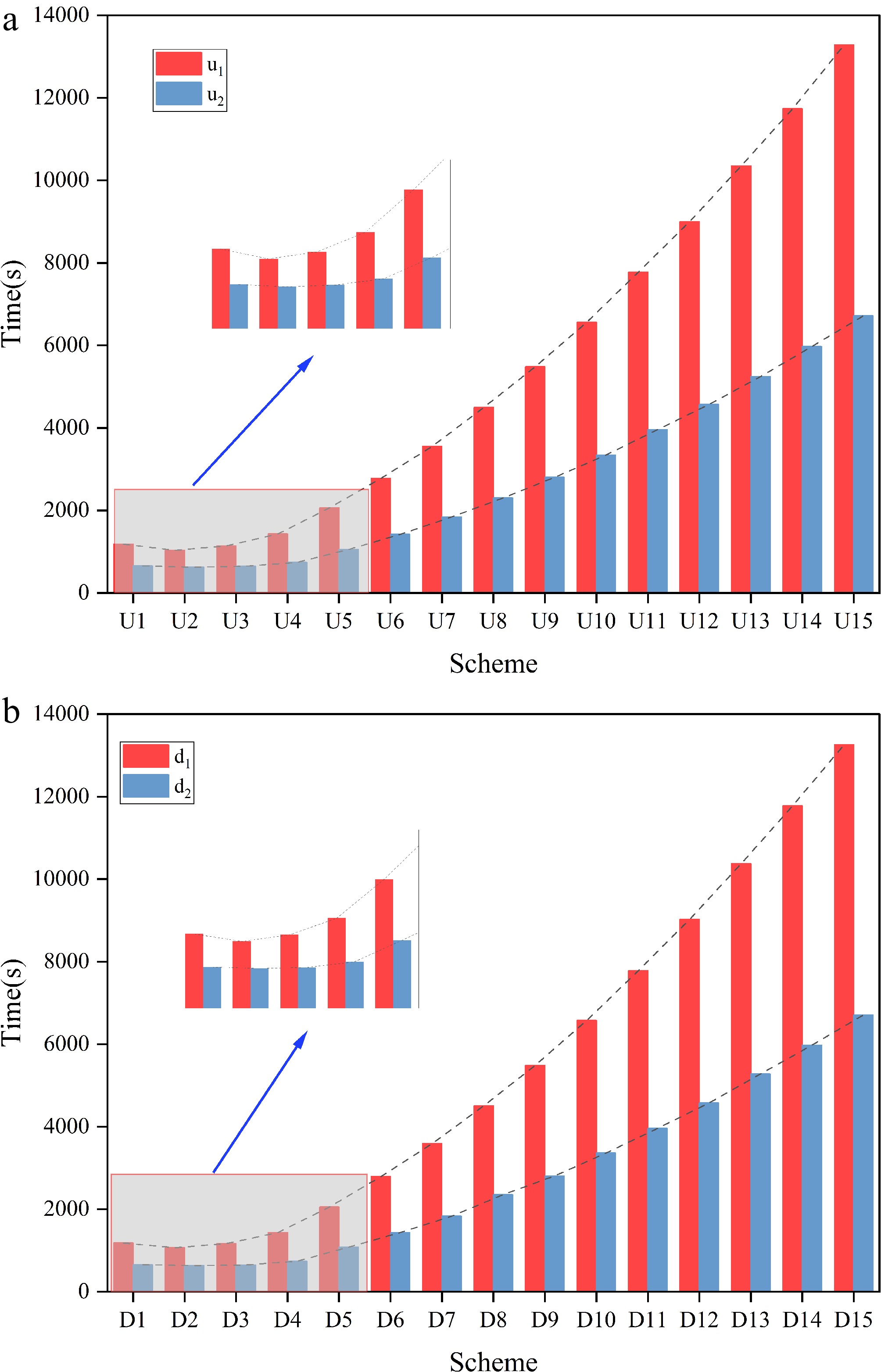

Figure 2.

Evacuation time results for different elevator floors for upward and downward movement. (a) Upward evacuation. (b) Downward evacuation.

Comparison of overall evacuation time

-

The comparison of upward and downward evacuation times under different scenarios involving the use of elevators on varying floors is presented in Fig. 2. Error bars are added to the figure, and the data errors stem from the stochastic nature of the simulation, which range from 6% to 8%, indicating good model stability. Figure 2 shows that the evacuation results of different scenarios for upward and downward movement exhibit a similar trend. This is mainly due to the fact that increasing the number of elevator service floors prolongs waiting time, causing congestion; this congestion further extends evacuation time and reduces evacuation efficiency, resulting in increased evacuation time across both modes. However, the specific evacuation time for each scenario differs. Scenarios U1 and D1 represent evacuation using only stairs, serving as baseline comparisons. For upward evacuation, it was observed that utilizing elevators on the 1st floor while employing stairs on all other floors (Scenario U2), and using elevators on the 1st and 2nd floors while utilizing stairs on the remaining floors (Scenario U3), significantly reduced evacuation times compared to other scenarios. Among these, Scenario U2 demonstrated the highest effectiveness in minimizing evacuation time.

For downward evacuation, the scenarios where elevators were used on the 10th floor only (Scenario D2) or on the 9th and 10th floors, with stairs utilized for the remaining floors (Scenario D3), markedly improved overall evacuation efficiency. Of these, Scenario D2 achieved the best evacuation performance. Notably, this trend remained consistent regardless of variations in the number of evacuees in the building. However, as the number of individuals using elevators increased, crowding at elevator entrances intensified, leading to prolonged waiting times and congestion, ultimately diminishing evacuation efficiency.

In summary, pedestrians on floors farther from the designated safe area face more significant challenges when evacuating via stairs. In such cases, prioritizing elevators' use for evacuation allows them to reach the safe zone more efficiently. This approach mitigates the decline in evacuation efficiency caused by fatigue and panic. It prevents congestion and potential conflicts with evacuees from other floors in the stairwells, thereby reducing overall evacuation pressure within the building more effectively. Consequently, the optimal strategy for upward evacuation is to prioritize using elevators for pedestrians on the lowest floors. Conversely, the most effective approach for downward evacuation is to utilize elevators for pedestrians on the highest floors.

The statistical results of upward and downward coordinated evacuations using stairs and elevators are presented in detail in Table 2. The table shows that the variation significantly influences the efficiency of coordinated evacuation in the number of evacuees. In this paper, R is defined as the optimization rate,

$R = \frac{{{T_{stairs}} - {T_i}}}{{{T_{stairs}}}}$ Additionally, it is essential to note that the efficiency of coordinated evacuation, for both upward and downward scenarios, demonstrates a clear improvement trend as the total number of evacuees decreases. Specifically, the shortest evacuation duration for stair and elevator coordinated evacuations occurs when there are 60 people per floor. Furthermore, comparing the evacuation results of upward and downward scenarios, reveals that when pedestrians evacuate solely by using stairs, the evacuation time for downward evacuation is shorter, while the efficiency of cooperative evacuation using stairs and elevators is considerably higher for upward evacuation than for downward evacuation. This phenomenon is mainly due to the fact that pedestrians need to overcome gravity to do work upwards to walk up the stairs, thus requiring approximately twice the heart rate, oxygen consumption, and physical exertion as walking down stairs[47]. Physical exertion affects the evacuation process, and walking speed is reduced when walking long distances on stairs. As a result, the staircase-only evacuation is faster when evacuating downward compared to evacuating upward. Reduced speed due to fatigue is universal, especially in mid- and high-rise floors, which leads to congestion at the rear and can seriously affect the evacuation speed. The EAE strategy solves the crowd evacuation process, which is susceptible to physiological factors, long evacuation paths, and prone to congestion, by using the elevator, and significantly improves the evacuation speed, compared to downward evacuation where the average speed is inherently higher, although EAE can also lead to an efficiency gains, their effect is not as significant as in the upward evacuation intervention process.

Comparative analysis of the cumulative flow of people

-

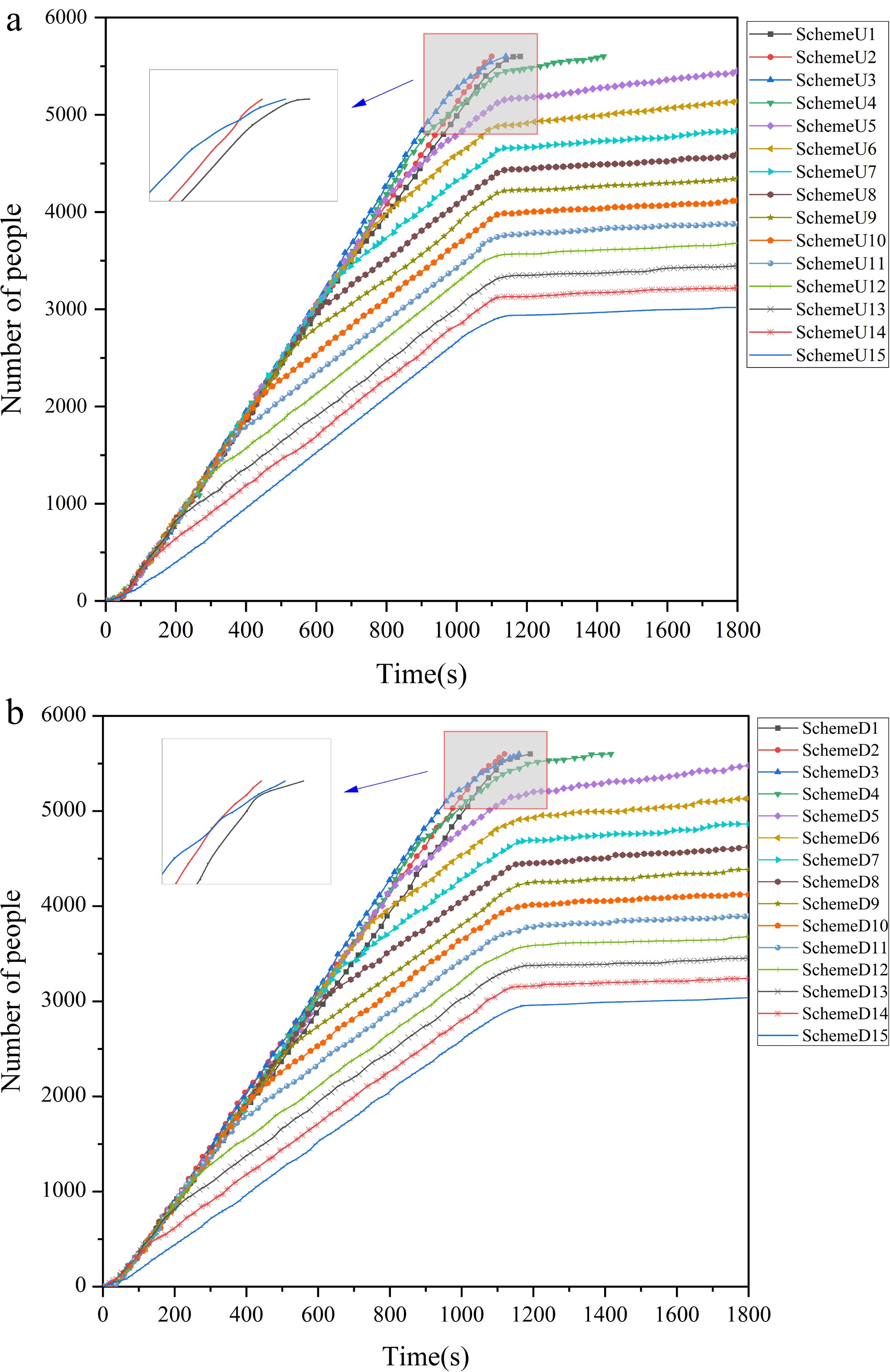

To further assess the findings, this section compares the cumulative flow of evacuees to the designated floors during upward and downward evacuation, respectively, to evaluate the efficiency of different evacuation strategies. Figure 3 presents the cumulative crowd flow data for upward and downward evacuation.

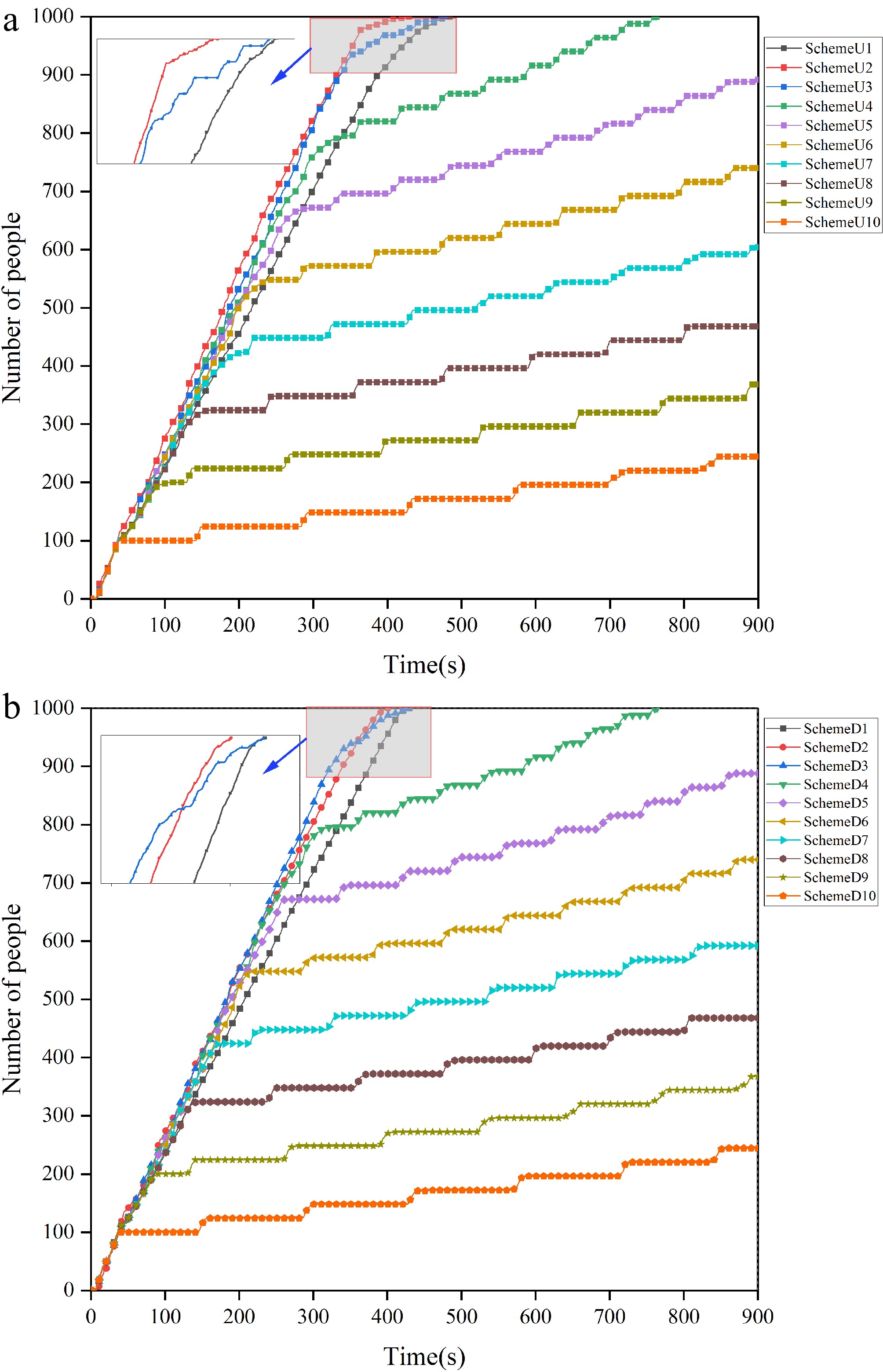

Figure 3.

Comparison of cumulative pedestrian flow for upward and downward evacuation. (a) Upward evacuation. (b) Downward evacuation.

As shown in Fig. 3a, during the same evacuation time for upward movement, the two scenarios—using the elevator on the 1st floor and stairs for pedestrians on the remaining floors (Scenario U2), and using the elevator on the 1st to 2nd floors with stairs for the rest of the floors (Scenario U3)—are the first to complete the accumulation of evacuees compared to the stair-only evacuation scenario (Scenario U1). Similarly, in Fig. 3b, the downward evacuation results reveal the accumulation of pedestrian flow in the scenarios where the elevator is used on the 10th floor with stairs for the remaining floors (Scenario D2), and on the 9th to 10th floors with stairs on the other floors (Scenario D3), was completed more quickly than the evacuation using stairs alone (Scenario D1).

In the remaining cases, at the onset of the evacuation, the time taken for coordinated evacuation using stairs and elevators was shorter than for evacuation using stairs alone. However, as the number of floors served by the elevators increased, the efficiency of elevator-assisted evacuation gradually decreased at different time points. Furthermore, the time required to reach these points increased with the number of floors utilizing elevators.

It is important to note that in the illustrations for Scenarios U3–U10 and D3–D10, there are several periods where the flow of pedestrians remains constant. This indicates that evacuees are waiting for the elevators during these times, which prolongs the evacuation duration. Moreover, as the number of floors served by the elevators increases, the frequency of such periods with constant flow also increases, suggesting a gradual decrease in evacuation efficiency. A comparison of the cumulative pedestrian flow diagrams, for both upward and downward evacuation shows that, for the same evacuation time, downward evacuation completes the accumulation of all evacuees earlier than upward evacuation. When both stairs and elevators are used to reduce evacuation time, upward evacuation benefits more significantly, reducing the time to accumulate evacuees more effectively than stair-only evacuation.

Comparison of evacuation times for stairs and elevators

-

Based on the above findings, further comparative analysis was conducted on the evacuation times for stairs and elevators during upward and downward evacuations. The results are shown in Fig. 4. The comparison reveals that, in the upward evacuation scenario, where only pedestrians on the lowest floor use the elevator while the others use the stairs, the elevator evacuees complete the evacuation first. A similar pattern is observed in the downward evacuation scenario, where only pedestrians on the top floor use the elevator; they are the first to complete their evacuation. In all other scenarios, pedestrians using the stairs evacuate more quickly.

Furthermore, as the number of floors served by the elevators increases, the evacuation time for the stairs gradually decreases, while the evacuation time for the elevators increases significantly. This is primarily because when too many people opt to evacuate via the elevator, congestion within the elevator occurs, leading to increased waiting times and, ultimately, a prolonged evacuation. This reduces the efficiency of elevator-assisted evacuation and may result in the under-utilization of stairs, negatively impacting the overall evacuation efficiency. Therefore, for upward and downward evacuations in buildings, it is critical to balance the proportion of people evacuating via stairs and elevators to optimize evacuation efficiency.

Impact of different proportions of people using elevators on upward and downward evacuation

Setting of different proportions of people using elevators

-

In the previous section, all pedestrians on different building floors were assumed to evacuate using elevators. The relationship between evacuation time and the number of floors using elevators was established by varying the number of floors where elevators were utilized. The findings indicated that for upward evacuation, the scenarios where elevators are used on the 1st floor only, or on the 1st and 2nd floors while the remaining floors use stairs, are the most effective in reducing evacuation time. For downward evacuation, the scenarios where elevators are used on the 10th floor only, or on the 9th and 10th floors while the rest of the floors use stairs, achieve the highest overall evacuation efficiency. Building on these conclusions, this section further examines the impact of varying the proportions of people using elevators on evacuation efficiency.

In the study of upward evacuation, the safety exit was set on the 10th floor. Firstly, only the 1st floor was set to be evacuated using elevators at the rate of 10%, 20%, 30%, ..., and 100% of pedestrians, respectively, and the rest of the pedestrians were evacuated using staircases (Scenario A), corresponding to the scenarios Um1–Um10. Then 10%–100% of pedestrians on floors 1 to 2 are evacuated using elevators, and the rest are evacuated using stairs (Scenario B), corresponding to scenarios Uk1–Uk10. For the study of downward evacuation, the safety exit is set on the 1st floor. Firstly, only 10%, 20%, 30%, ..., and 100% of pedestrians on the 10th floor are set to use the elevator to evacuate, and the rest of the pedestrians use the staircase to evacuate, which corresponds to the scenarios Dm1–Dm10. Then, 10%–100% of pedestrians on floors 9 to 10 are evacuated using elevators, and the rest are evacuated using stairs, corresponding to scenarios Dk1–Dk10. In the simulations, each building floor was populated with 100 individuals, randomly distributed. Table 3 provides a detailed overview of the simulation scenarios, illustrating the effects of varying the proportions of elevator users during upward and downward evacuation.

Table 3. Simulation scenarios for different proportions of people using elevators during upward and downward evacuation in scenarios A and B.

No. Scenarios A Scenarios B Upward scenario description Um Downward scenario description Dm Upward scenario description Uk Downward scenario description Dk 1 10% by elevator on the 1st floor 10% by elevator on the 10th floor 10% by elevator on floors 1–2 10% by elevator on floors 9–10 2 20% by elevator on the 1st floor 20% by elevator on the 10th floor 20% by elevator on floors 1–2 20% by elevator on floors 9–10 3 30% by elevator on the 1st floor 30% by elevator on the 10th floor 30% by elevator on floors 1–2 30% by elevator on floors 9–10 4 40% by elevator on the 1st floor 40% by elevator on the 10th floor 40% by elevator on floors 1–2 40% by elevator on floors 9–10 5 50% by elevator on the 1st floor 50% by elevator on the 10th floor 50% by elevator on floors 1–2 50% by elevator on floors 9–10 6 60% by elevator on the 1st floor 60% by elevator on the 10th floor 60% by elevator on floors 1–2 60% by elevator on floors 9–10 7 70% by elevator on the 1st floor 70% by elevator on the 10th floor 70% by elevator on floors 1–2 70% by elevator on floors 9–10 8 80% by elevator on the 1st floor 80% by elevator on the 10th floor 80% by elevator on floors 1–2 80% by elevator on floors 9–10 9 90% by elevator on the 1st floor 90% by elevator on the 10th floor 90% by elevator on floors 1–2 90% by elevator on floors 9–10 10 100% by elevator on the 1st floor 100% by elevator on the 10th floor 100% by elevator on floors 1–2 100% by elevator on floors 9–10 The change of evacuation efficiency under different pedestrian distribution

-

When only pedestrians on floor 1 (or the 10th floor) evacuate using the elevator, while pedestrians on other floors evacuate via stairs, the simulation results for varying proportions of elevator users are shown in Fig. 5a. Similarly, when pedestrians on floors 1–2 (or floors 9–10) evacuate using the elevator, and the rest use stairs, the results are presented in Fig. 5b.

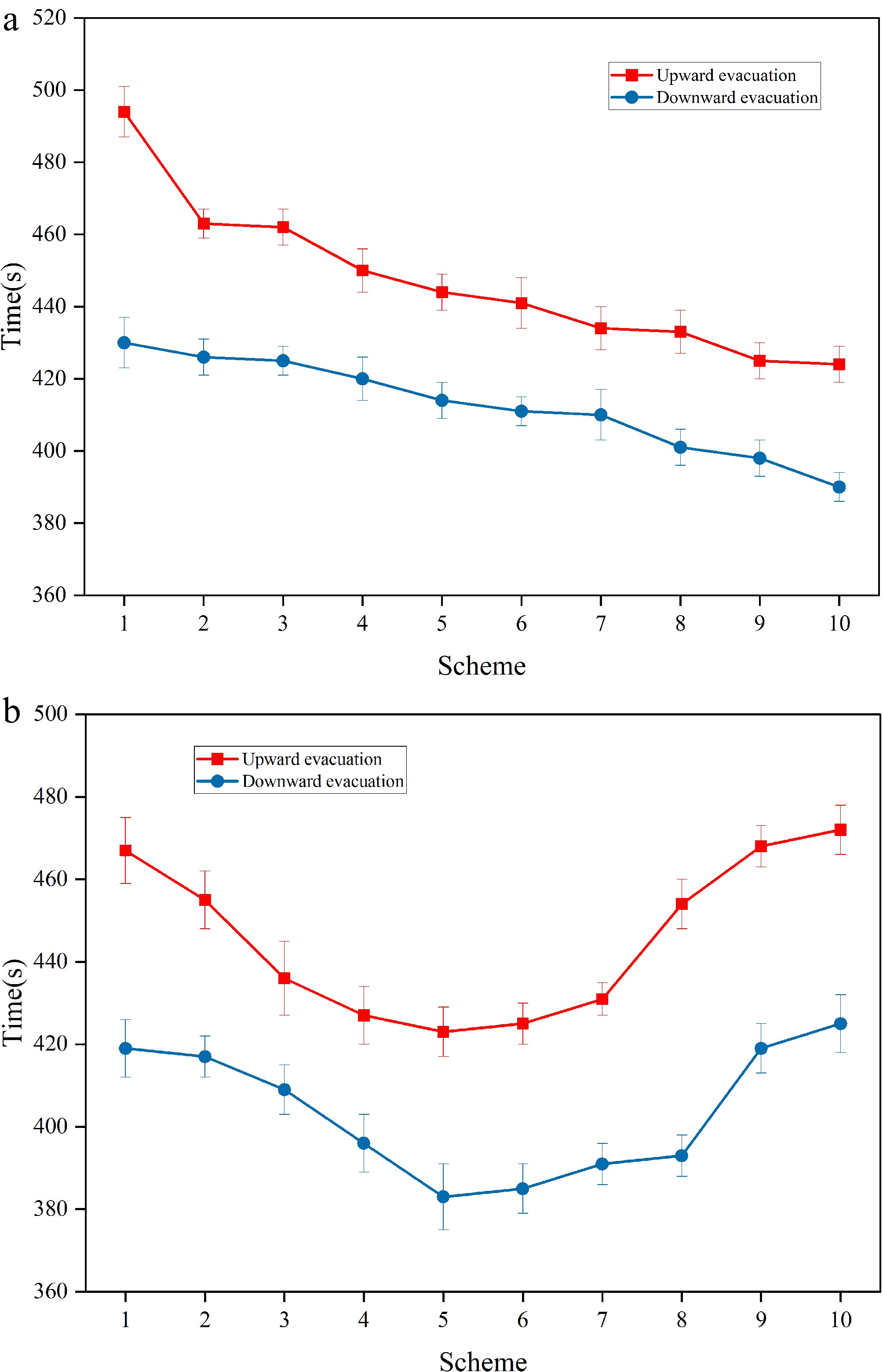

Figure 5.

Simulation results of the use of elevators by different proportions of people during upward and downward evacuations. (a) Scheme A. (b) Scheme B.

Figure 5a demonstrates that during upward evacuation, when only pedestrians on the bottom floor use the elevator, the evacuation time decreases as the proportion of elevator users increases. Based on the findings in the previous section, it was found that pedestrians using elevators were able to be the first to complete the evacuation when only the pedestrians on the bottom floor chose to use elevators to evacuate, and the rest of the people used stairs to evacuate. Therefore, increasing the proportion of bottom-floor pedestrians using the elevator results in progressively shorter evacuation times. The optimal strategy for upward evacuation is thus to have all pedestrians on the lowest floor evacuate via the elevator, while others use stairs. For downward evacuation, the shortest evacuation time is achieved when all pedestrians on the top floor evacuate using elevators, while the remaining floors use stairs.

As shown in Fig. 5b, the shortest evacuation time for upward evacuation is achieved when 50% of the pedestrians on floors 1 to 2 use the elevator, while the remaining 50% evacuate via stairs. In this case, the evacuation time decreases and then increases with the proportion of people using elevators. Similarly, for downward evacuation, the shortest evacuation time occurs when 50% of the pedestrians on floors 9 to 10 use the elevator, with the rest opting for the stairs. This is because the overall efficiency of the evacuation system hinges upon the dynamic matching of flow rates between stairwells and elevators. When elevator utilisation is excessively low, the advantage of rapid vertical transport remains underutilised, preventing the system from achieving optimal performance. Conversely, when utilisation is excessively high, it triggers congestion and queuing at elevator entrances while simultaneously leaving stairwell resources idle, resulting in a net decrease in the overall efficiency of both resources. Consequently, the optimal scenario—whether all occupants on the top (or bottom) floor using elevators, or 50% of occupants on the top and second-top (or bottom and second-bottom) floors using elevators—essentially represents the critical equilibrium point where the system balances the vertical transit time saved by elevators against the increased waiting time caused by congestion.

In summary, the optimal coordinated evacuation strategies for minimizing evacuation time are as follows: (1) upward evacuation: The shortest time is achieved either when 100% of pedestrians on the bottom floor use the elevator while others use stairs, or when 50% of the pedestrians on each of floors 1 to 2 use the elevator; (2) downward evacuation: the shortest time is attained when 100% of the pedestrians on the top floor use the elevator, or when 50% of those on each floor 9 to 10 evacuate using the elevator.

-

The super high-rise building in the example serves as a significant public space with a diverse and complex occupant composition, so conducting unannounced fire drills is impractical. Fire drills with prior notice often yield results that deviate significantly from real-life evacuation scenarios. Small-scale crowd evacuation experiments also fail to replicate the complexity and dynamics of emergency evacuations in large, high-rise structures. Consequently, this section employs simulation as a method to evaluate the impact of elevator-assisted evacuation on evacuation efficiency in actual super high-rise buildings.

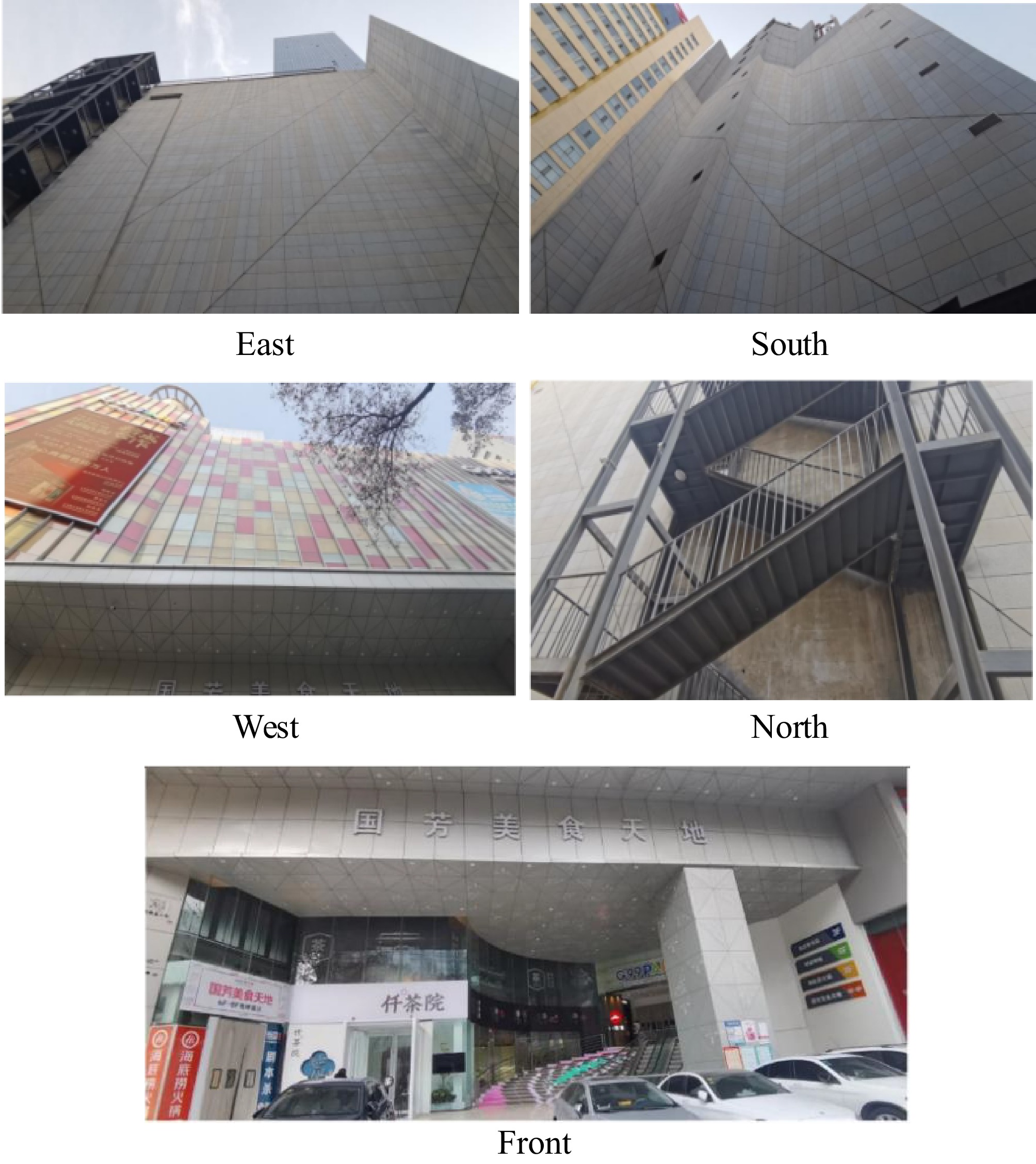

Evacuation example model building

-

The Guofang Parkson building, a substantial mixed-use structure, consists of 40 floors with a total height of 146 m. It is primarily an office and commercial building. According to the architectural drawings and building details, floors 1 to 10 are designated as commercial areas, with a floor height of approximately 5.1 m; floors 11 to 24, and 26 to 39 serve as business office areas; the 25th floor is a refuge floor, after arriving at the refuge floor, personnel are spread evenly throughout the safe area for temporary assembly without becoming stranded or congested, and the 40th-floor houses equipment, with a height of 3 m. Each floor has a single-floor area of 1,022.94 m2. The building's total area is 31,998 m2, and the average office floor accommodates approximately 200 occupants per floor. The fire safety infrastructure includes a fire control room located in the northwest corner of the 1st floor, two fire water tanks situated on the roof of the 40th floor, and two fire pools with a combined capacity of 768 m3. The elevation and panoramic view of the building is presented in Fig. 6, while the evacuation scene plan used for simulation is shown in Fig. 7. This paper selects the Guofang Parkson super high-rise building as the simulation object to analyze evacuation scenarios and strategies effectively.

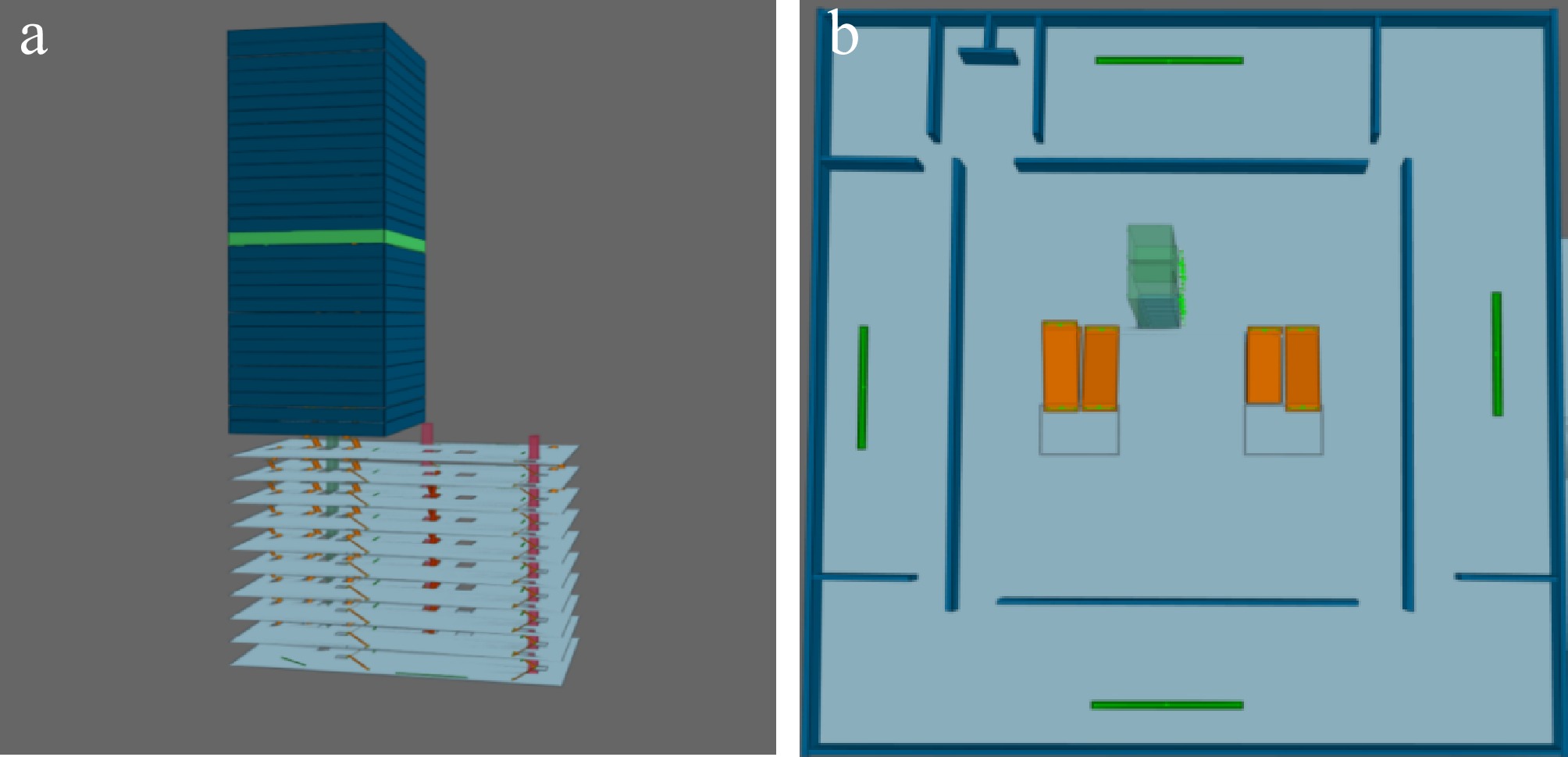

Figure 7.

Simplified structural diagrams of super high-rise buildings. (a) Perspective view. (b) Top view.

Based on the actual scenarios, this chapter establishes disaster scenario assumptions. The super high-rise building includes business offices on floors 11 to 24, and 26 to 39, with the 25th floor designated as a refuge floor. In the assumed scenario, a fire occurs on the 10th floor of the building, preventing occupants above the 10th floor from safely evacuating to the ground floor exits. These occupants must urgently evacuate to the 25th refuge floor to avoid danger. This chapter examines the efficiency of coordinated evacuation strategies using stairs and elevators in high-rise buildings, focusing on the efficiency differences between upward elevator evacuation from floors 11 to 24 and downward elevator-assisted evacuation from floors 26 to 39 during simultaneous upward and downward evacuation operations.

The architectural CAD drawings of the building were imported into the MassMotion software. Based on these drawings, a scaled evacuation model of the building was constructed with necessary simplifications, as shown in Fig. 7. During the simulation process, the actual number of people in the building was considered, with 200 pedestrians assigned to each floor, resulting in a total of 5,600 people requiring evacuation. A control group was set with 100 pedestrians per floor to provide a more comprehensive evaluation of evacuation efficiency, allowing for comparison with the previous model. The relevant elevator parameters used in the simulation are consistent with the settings described in the last section, ensuring uniform experimental conditions. The specific simulation conditions are detailed in Table 4, the number of upward evacuation scenarios are labeled u1–u2, and the corresponding number of downward evacuation scenarios are labeled d1–d2.

Table 4. Simulation scenarios for the use of elevators on different floors during upward and downward evacuation.

No. Upward scenario description Un Downward scenario description Dn 1 11–39 floors by stairs only 11–39 floors by stairs only 2 11 floors by elevator, the rest by stairs 39 floors by elevator, the rest by stairs 3 11–12 floors by elevator, the rest by stairs 38–39 floors by elevator, the rest by stairs 4 11–13 floors by elevator, the rest by stairs 37–39 floors by elevator, the rest by stairs 5 11–14 floors by elevator, the rest by stairs 36–39 floors by elevator, the rest by stairs 6 11–15 floors by elevator, the rest by stairs 35–39 floors by elevator, the rest by stairs 7 11–16 floors by elevator, the rest by stairs 34–39 floors by elevator, the rest by stairs 8 11–17 floors by elevator, the rest by stairs 33–39 floors by elevator, the rest by stairs 9 11–18 floors by elevator, the rest by stairs 32–39 floors by elevator, the rest by stairs 10 11–19 floors by elevator, the rest by stairs 31–39 floors by elevator, the rest by stairs 11 11–20 floors by elevator, the rest by stairs 30–39 floors by elevator, the rest by stairs 12 11–21 floors by elevator, the rest by stairs 29–39 floors by elevator, the rest by stairs 13 11–22 floors by elevator, the rest by stairs 28–39 floors by elevator, the rest by stairs 14 11–23 floors by elevator, the rest by stairs 27–39 floors by elevator, the rest by stairs 15 11–24 floors by elevator, the rest by stairs 26–39 floors by elevator, the rest by stairs Analysis of evacuation time under different evacuation strategies

-

Figure 8 compares upward and downward selected elevator-assisted evacuation times for different evacuation strategies. As shown in Fig. 8, when pedestrians in the building are evacuated, the time for coordinated evacuation by stairs and elevators increases with the number of floors evacuated using elevators. After an in-depth study, it was found that upward evacuees using elevator-assisted evacuation, the evacuation time is less than the other scenarios when the 11th floor is selected for elevator evacuation, the rest of the floors are chosen for stair evacuation, and when the 11th–12th use elevators evacuate, the rest of the floors are chosen for stair evacuation. In the case of downward evacuation, it was found that downward evacuees using elevator-assisted evacuation, the evacuation time is less than the other scenarios when the 39th floor is selected for elevator evacuation, the rest of the floors are chosen for stair evacuation, and when the 38th–39th floors are evacuated by elevator, the rest are evacuated by stair evacuation. The scenario with the shortest evacuation time obtained by using elevators for upward evacuation was the 11th floor choosing to evacuate by elevators and the rest of the floors evacuating by stairs (Scenario U2), while the scenario with the shortest evacuation time obtained by using elevators for downward evacuation was the 39th-floor using elevators and the rest of the floors still using stairs (Scenario D2). Significantly, neither of the scenarios corresponding to these two shortest evacuation times is affected by changes in the number of evacuees in the building, which is consistent with the results of the previous study. Specifically, when the number of evacuees is 200, the shortest evacuation time obtained for scenario U2 in the upward evacuation is reduced by 12.4% compared to the staircase-only evacuation. In comparison, the shortest evacuation time for scenario D2 in the downward evacuation is reduced by 9.8%. This result suggests that the use of elevator-assisted evacuation is more favorable for both upward and downward pedestrian evacuation of high-rise buildings than for downward evacuation, and this pattern is consistent with the results of the previous study.

Figure 8.

Evacuation time results for different floors used by upward and downward elevators. (a) Upward evacuation. (b) Downward evacuation.

Comparison of pedestrian flow on refuge floors

-

Figure 9 provides a detailed comparison of people flow during upward and downward evacuations to the refuge floor. The figure illustrates that the cumulative people flow trends for both upward and downward evacuations are similar. Over time, the flow of evacuees reaching the refuge floor increases gradually in both scenarios. When comparing the different evacuation scenarios, when the time for combined stair and elevator evacuation is less than for stair-only evacuation, the time to reach the maximum flow rate is lower than for stair-only evacuation. However, when the time for stair and elevator co-evacuation is higher than the time for stair-only evacuation, although an initial increase in the number of people evacuating using the elevator leads to a higher evacuation rate than stair-only evacuation, the evacuation rate then decreases gradually at different time points due to an increase in the number of people waiting for the elevator, the turning point in Fig. 9. As the proportion of evacuees relying on elevators increases, the waiting time for elevators grows correspondingly. This increase leads to pedestrian congestion at elevator entrances, reducing the use of stairs, and negatively impacting evacuation efficiency. Consequently, this congestion results in longer overall evacuation times, underscoring the need for careful coordination between elevator and stair usage to optimize evacuation strategies.

Figure 9.

Cumulative flow of people at the upward and downward evacuation levels. (a) Upward evacuation. (b) Downward evacuation.

Comparing and analyzing the evacuation time and efficiency results from the above simulation with previous conclusions, it is evident that the evacuation simulation outcomes for this super high-rise building align with those of the earlier simplified model. Despite differences in evacuation scenarios, the principles governing the coordination of stairs and elevators in evacuation efficiency remain consistent. Specifically, evacuation efficiency in high-rise buildings decreases as the number of floors relying on elevators for evacuation increases. When elevator-assisted evacuation reduces the overall evacuation duration, the efficiency of upward evacuation using elevators is notably higher than that of downward evacuation. Furthermore, this trend remains unaffected by variations in the number of evacuees within the building. These findings provide a crucial theoretical foundation for optimizing evacuation strategies in high-rise buildings, ensuring more efficient and effective emergency responses.

Stair and elevator cooperative evacuation strategy summary

-

The above analysis highlights the crucial role of synergy between stairs and elevators in improving evacuation efficiency during both upward and downward evacuations in high-rise buildings. Based on these insights, this section summarizes the critical synergistic evacuation strategies for stairs and elevators derived from the research in this paper:

(1) Prioritizing elevator use for upward evacuation: stairs and elevators are the primary evacuation tools in high-rise buildings. While stairs are more efficient for downward evacuation, their use in upward evacuation is less effective due to the physical exertion required from pedestrians. However, incorporating elevators as a supplementary evacuation method significantly enhances the efficiency of upward evacuation. Therefore, in an emergency in the building, if upward evacuation is required, it is beneficial to prioritize using elevators to assist with evacuation;

(2) Reasonable allocation of pedestrians using elevators: the analysis revealed that if too many people opt for elevator evacuation, it can lead to congestion within the elevators and reduce the efficiency of the stairs. Pedestrians farther from the safe floor may find it difficult to evacuate via stairs, making elevators more suitable for these individuals. Prioritizing elevator use for those farther from the safe floor can accelerate evacuation to the secure area, reducing fatigue, panic, and stairwell congestion. This strategy also helps to alleviate evacuation pressure throughout the building. Specifically, for upward evacuations, it is recommended to prioritize all pedestrians on the lowest floor for elevator use, with the rest of the building's occupants using the stairs. For downward evacuation, priority can be given to evacuating all pedestrians from the top floor using elevators, with the remaining floors evacuating by stairs, achieving optimal evacuation efficiency.

It should be particularly noted that the 'bottom-up priority and top-down priority' strategy proposed by this research institute constitutes fundamental guidelines and quantitative benchmarks established under the idealised premise that fire sources have not obstructed stairwell access routes. It is not intended as a definitive solution applicable to all scenarios. This strategy aims to provide the core logic for future development of more sophisticated adaptive evacuation systems, thereby laying a robust theoretical foundation for optimising evacuation plans in high-rise buildings and enhancing overall emergency evacuation efficiency.

-

This study primarily investigates the impact mechanism of stair and elevator-assisted evacuation strategies on evacuation efficiency in high-rise buildings during emergencies. A simulation model for high-rise buildings was developed, and the influence of different stair and elevator-assisted evacuation strategies for both upward and downward evacuation needs was examined under various conditions.

The main findings are as follows:

(1) An increase in the number of evacuees leads to longer evacuation times, with upward evacuation generally requiring more time than downward evacuation when only stairs are used. However, when elevator assistance is incorporated, the evacuation optimization rate for upward evacuation exceeds that for downward evacuation, regardless of the number of evacuees. This suggests that in the event of an incident in a high-rise building, priority should be given to utilizing elevators for upward evacuation when both upward and downward evacuations are required simultaneously;

(2) Coordinated evacuation by stairs and elevators does not always improve evacuation efficiency. The improvement of evacuation efficiency is concentrated when the lowest or second-lowest floor (highest or second-highest floor) personnel use the elevator, regardless of the number of evacuees. This finding emphasizes that in the case of an emergency in a high-rise building, for upward evacuation, priority should be given to allowing the lowest floors to use elevators, while for downward evacuation, the highest floors should be prioritized;

(3) The proportion of people using elevators can influence evacuation times notably. The optimal evacuation strategy for minimizing evacuation time is to have all evacuees from the most critical floors use elevators, with the rest using stairs. Alternatively, having 50% of evacuees from the lowest and second-lowest floors, or 50% from the highest and second-highest floors, use elevators, and the rest use stairs, also yields an efficient evacuation outcome.

An actual application scenario of a super high-rise building with the design of refuge floors was used to deeply analyzes the application effect of the cooperative evacuation strategy of stairs and elevators. The simulation results for the super high-rise building aligned with those from the simplified model, demonstrating the feasibility of applying the coordinated evacuation strategy in real-world scenarios. We hope to apply the simulation results in practice. For future applications, when evacuating upwards, priority will be given to occupants on the lowest floor or 50% of occupants on each of the two lowest floors to use elevators. When evacuating downwards, priority will be given to occupants on the highest floor or 50% of occupants on each of the two highest floors. It is recommended that at least two elevators be assigned to serve priority floors to ensure adequate capacity.

However, this study has certain limitations. Firstly, the evacuation simulation is based on the assumption of random distribution of personnel characteristics and does not sufficiently account for the complex behavioural impacts of psychological factors such as panic, which differs from real-world scenarios. Moreover, while the proposed strategy of 'bottom-up priority and top-down priority' provides a valuable foundational framework, its effectiveness could be enhanced by incorporating dynamic elements to adapt to unpredictable fire locations. Consequently, a key evolutionary direction involves upgrading the current static principles into a dynamic intelligent system. Future research could focus on constructing a comprehensive simulation framework that integrates fire physics with human psychology, and developing a complete intelligent evacuation system based on this foundation. This system should incorporate the following components: a fire perception module for real-time detection of fire sources and smoke; a path evaluation module for dynamically assessing route feasibility; and a dynamic decision-making module capable of adjusting elevator priority in real time. This would enable autonomous optimisation of evacuation strategies and robust adaptability to complex scenarios.

This research was sponsored by the Jiangsu Provincial Basic Research Program for Outstanding Youth Fund Project (BK20250135),the National Natural Science Foundations of China (No. 52374208), the Major Natural Science Research Projects in Colleges and Universities of Jiangsu Province (No. 23KJA620002), Excellent Engineer Training Program of Nanjing Tech University (No. ZYXM202402), and a project funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Zhang X, Shao X; data collection: Shao X; analysis and interpretation of results: Zhang X, Wang J, Li J, Wu J; draft manuscript preparation: Shao X. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Tech University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang X, Shao X, Wang J, Li J, Wu J. 2025. Research on the rules and strategies of coordinated evacuation of stairways and elevators in high-rise buildings. Emergency Management Science and Technology 5: e018 doi: 10.48130/emst-0025-0017

Research on the rules and strategies of coordinated evacuation of stairways and elevators in high-rise buildings

- Received: 13 June 2025

- Revised: 30 September 2025

- Accepted: 11 October 2025

- Published online: 28 October 2025

Abstract: In high-rise emergencies, relying solely on stairs for evacuation may hinder timely escape. Therefore, elevator-assisted stair evacuation should be considered to improve efficiency. Limited research exists on coordinated stair-elevator evacuation, particularly for upward and downward movements involving refuge floors. A 10-story case study was constructed using MassMotion software, based on the Social Forces Model, to explore the effects of elevator-served floor, building population, and percentage of the population using the elevator on evacuation. Findings were applied to a real building. Results indicate that evacuation time increases with the number of elevator-served floors. Upward stair-elevator coordination outperformed downward evacuation, unaffected by building population. For upward evacuation, deploying elevators on floors 1 or 1–2 reduced evacuation times compared to stairs alone. Downward evacuation achieved time savings using elevators on floors 10 or 9–10. Allocating elevators to 100% of occupants on the lowest or highest floors, or 50% on floors 1–2 for upward, or 9–10 for downward evacuation, minimized evacuation duration. Elevator-assisted evacuation reduced evacuation times by 11.7% for upward evacuation, and 8.4% for downward evacuation, suggesting prioritization of elevators for upward evacuees. This research provides theoretical insights for optimizing the coordination of stairs and elevators in high-rise building evacuations.