-

With the increasing utilization of biomass as a low-carbon fuel, biomass combustion becomes a major anthropogenic source of oxygenated aromatics (e.g., cresol isomers)[1−3]. Lignin degradation[4] and wildfire[5] are two other biogenic sources. The oxygenated aromatics possess higher danger compared to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH). They may quickly convert to secondary organic aerosol via photochemical reactions with OH radicals, NO3, and O3, and they are precursors for oxygenated PAHs and soot with higher toxicity[6,7]. Unravelling cresol formation chemistry may help understand how oxygenated aromatics are produced in the combustion process, and develop reaction control strategies to minimize emissions.

The molecular structures of lignin from various sources are large and complicated. Based on the observation of abundant benzyloxy functional groups in the molecular structures of lignin, anisole was proposed and widely used as a surrogate to represent the combustion characteristics[8]. Many previous studies have focused on the fundamental pyrolysis/combustion chemistry of anisole in various reactors and reaction conditions for different measurement targets: shock tube[9−11] and rapid compression machine[9] for ignition delay time; Bunsen burner[12], heat flux burner[8], combustion vessel[13], and laminar flame burner[14] for laminar burning velocity; flow reactor[15−21], jet stirred reactor[14,22,23], premixed[24−27] and diffusion[28] flames for speciation data. Kinetic models[8,20,23,29−34] were also proposed to describe the combustion/pyrolysis chemistry of anisole. However, all kinetic models treat cresol isomers as one lumped species with roughly estimated rate constants, while the molecular structure of cresol isomers might be vital for oxygenated PAHs (OPAHs) growth[22]. Considering that the substituent site of methyl and hydroxyl groups in cresol may have a significant effect on their tendency to produce OPAHs, cresols need to be de-lumped with detailed reaction pathways with more accurate rate constants.

In this work, a systematic investigation of cresol formation from anisole is performed. Reaction pathways were proposed based on high-level quantum chemistry calculations, followed by product yield and kinetic analyses to evaluate the competition of cresol formation with other by-products. The proposed reaction pathways were then implemented into the LLNL model[8], and examined against measured speciation data of cresols. Instead of developing a new anisole kinetic model, the purpose of this work is to de-lump cresol isomers, investigate, and examine the proposed cresol formation pathways.

-

The local minimum and transition state structures in all explored reaction pathways were optimized at the DFT/B3LYP/6-311 G+(d,p) level, and the M06-2X/6-311 G+(d,p) method was used to describe the minimum energy pathway (MEP). The frequencies used for reaction rate calculations were obtained using the same methods with a correction factor of 0.967[35]. To improve the energy accuracy, single-point energies of each structure were further refined using the G4 method with geometry optimized at the DFT/B3LYP/6-311/G+(d,p) level. Bond scans were conducted to efficiently locate the correct transition state, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S1. All transition states were carefully examined by the intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) calculations to ensure that the transition state connects the reactants and products. A 1D hindered rotor was applied for thermal correction. The real frequencies below 100 cm−1 were carefully examined. In this treatment, the rotational constants and torsional potential energies are required as inputs. To obtain these parameters, relaxed potential energy surface (PES) scans were performed with a dihedral angle increment of 20° employing the DFT/B3LYP/6-311G+(d,p) method. Instead of considering conformer search, the transition states were found following the minimum energy principle. All quantum chemistry calculations were performed using Gaussian 09 software package (version D.01)[36].

Most of the reactions in cresol formation are bimolecular reactions. The pressure-dependence of reaction rate coefficients in bimolecular reactions is expected to be ignorable according to previous studies[37]. For the unimolecular reaction like phenoxy + CH3 → o-cresol, the pressure dependence is found to be marginal (Supplementary Fig. S2). In this work, all reaction rate coefficients were initially evaluated at the high-pressure limit. Then, the pressure dependence of important reactions was examined using the RRKM theory by solving the master equation (RRKM-ME) method. High-pressure limit rate coefficients for reactions with tight transition states were evaluated by transition state theory (TST) based on the frequencies, energy barriers, and molecular information from quantum chemistry calculations. It was visually confirmed that each point contains a frequency with vibration corresponding to motion along the MEP.

The pressure-dependent reaction rate coefficients were calculated in the pressure range of 0.1−100 atm, and temperature range of 700−2,500 K via RRKM-ME using the MultiWell program suite[38]. The maximum energy was set as 300,000 cm−1. The translational and vibrational temperatures were treated as the same in simulations. To accurately describe the sums and densities of states, an energy grain size of 10 cm−1 was used. The collisional energy transfer was described by the temperature-independent exponential-down model (ΔEdown = 260 cm−1). It is noteworthy that the reaction rate coefficients are not very sensitive to the choice of the collisional energy transfer model, as indicated in our previous study[39] where both temperature-independent exponential-down model (ΔEdown = 260 cm−1), and temperature-dependent exponential-down model (ΔEdown = 200 × (T/300 K)0.85 cm−1)[40] were examined. Argon was the bath gas collider with Lennard-Jones parameters σ and ԑ/kB of 3.47 Å and 114 K. The Lennard-Jones parameters of other species were assumed to be the same as those of anisole, with σ and ε/kB equaling 5.68 Å and 495.3 K, respectively. The product yield was calculated by initiating the reactions with chemical activation energy distribution at different temperatures and pressures. The calculation time was long enough for the bimolecular reaction to reach equilibrium. These branching fractions were then multiplied by the overall high-pressure limit rate constants to yield the individual formation rates for each product at different temperatures. The resulting rate constants for each elementary step were subsequently regressed to the modified Arrhenius equation to acquire the kinetic parameter. The uncertainties of calculated rate constants of multiwall and multichannel reactions are expected to be within a factor of three[41,42].

The enthalpies of formation at 0 K were calculated by the atomization method using the G4 method[43] for new species. The temperature-dependent formation enthalpies, entropies, and heat capacities were evaluated by statistical thermodynamics in the MultiWell suite[38].

Kinetic modelling

-

The base anisole model is proposed by Wagnon et al.[8], in which anisole decomposition is already well established. This model has been widely validated against ignition delay time, laminar burning velocity, and speciation data in a jet stirred reactor, and it can reproduce most of the experimental measurements, while other models[20,23,30] have larger prediction discrepancies in general. A detailed description of the LLNL model can be found in previous literature[8]. However, cresol isomers were lumped in the LLNL model, and the reaction rate constants to produce cresols (methyl radical addition on phenol or phenoxy, O-atom insertion of toluene, and OH ipso-substitition of toluene and xylene) are roughly estimated by analogy. To de-lump cresol isomers, the investigated cresol formation pathways with more accurate reaction rate coefficients, and thermodynamics for new species were implemented into the LLNL model. Meanwhile, the reaction pathway implementation should not influence the good prediction capability of other targets, e.g., ignition delay time, flame speed, and speciation data for reactants, main products, and important intermediates. The kinetic model files are provided in Supplementary File 1.

The LLNL model with and without implementing cresol formation pathways was used for model comparison to indicate the difference. Numerical simulations were performed by ANSYS Chemkin 19.1 software[44]. For the counterflow diffusion flame, the boundary conditions were the same as reported in the literature[28]. The strain rate is 80 s−1. The inlet composition of the fuel side is anisole 0.05, CH4 0.1, Ar 0.65, and CO2 0.2. The composition of the oxidizer side is O2 0.5 and Ar 0.5. Momentum balance was achieved, and the distance between the fuel side nozzle and the oxidizer side nozzle is 10 mm. For jet stirred reactor simulation, a transient solver was used with identical boundary conditions as experiments reported in the literature[8,23].

-

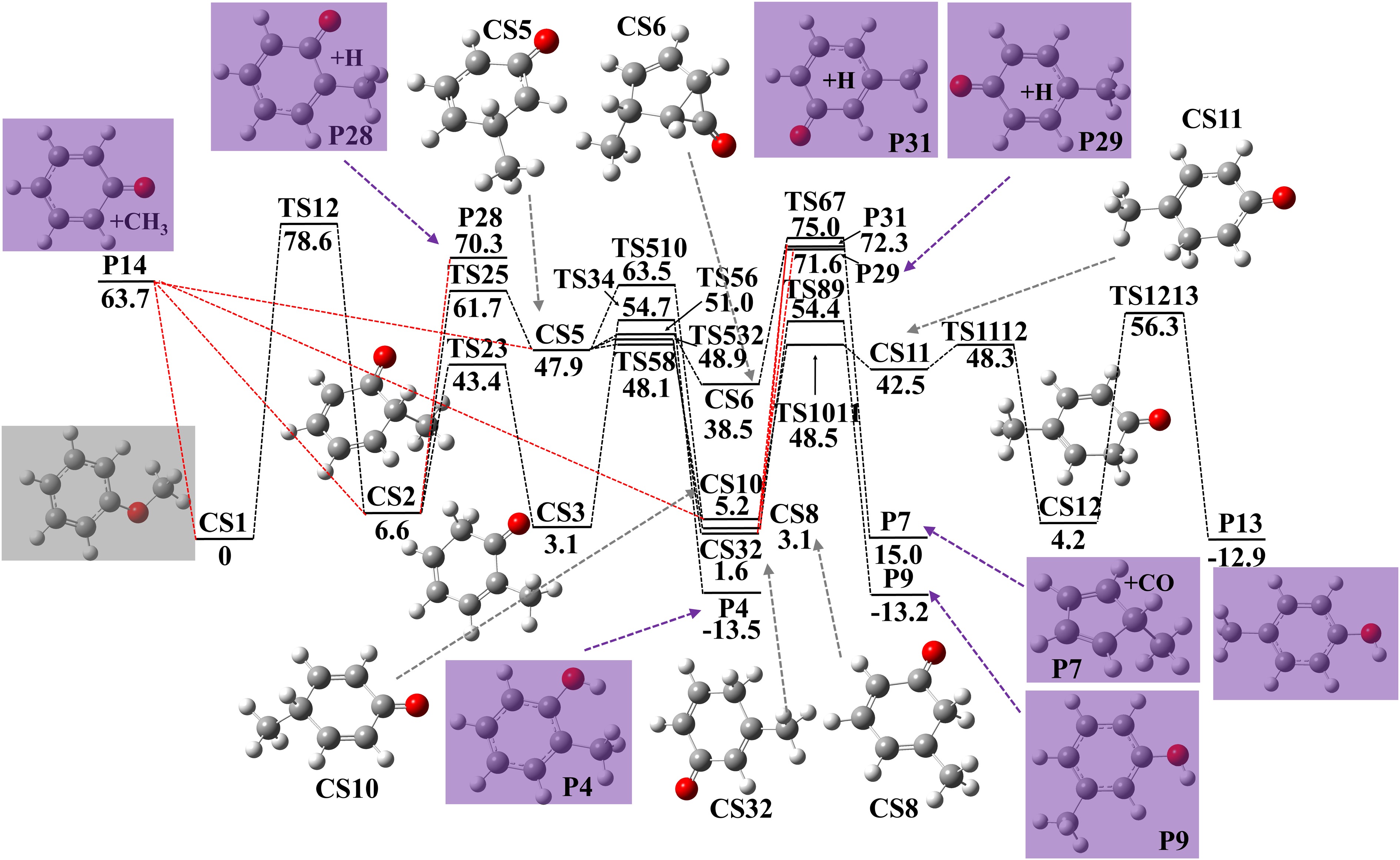

The proposed direct reaction pathways of cresol formation from anisole are presented in Fig. 1. There are two initiation reactions, unimolecular decomposition (CS1 → P14, E = 63.7 kcal·mol−1) and intermolecular CH3 migration (CS1 → CS2, E = 78.6 kcal·mol−1). The lower energy barrier of unimolecular decomposition makes it the favored one to produce phenoxy radical and methyl radical. Barrierless recombination of these two radicals yields CS2, CS5, and CS10. H-atom elimination of CS2 produces P28 with a high energy barrier of 63.7 kcal·mol−1. Alternatively, CS2 could react through internal H-atom migration (CS2 → CS3, E = 36.8 kcal·mol−1), or CH3 migration (CS2 → CS5, E = 55.1 kcal·mol−1) with low energy barriers. The low energy barrier of CS2 → CS3 results from a six-membered ring cyclic transition state. CS5 can also be produced through the recombination of methyl radical and phenoxy radical (P14). H-atom loss of CS3 produces o-cresol (CS3 → P4, E = 51.6 kcal·mol−1). For CS5, it has four pathways: CH3 migration to CS10 (CS5 → CS10, E = 15.6 kcal·mol−1), internal H-atom migration to CS8 (CS5 → CS8, E = 0.2 kcal·mol−1), internal H-atom migration to CS32 (CS5 → CS32, E = 1.0 kcal·mol−1), and cyclization to CS6 (CS5 → CS6, E = 3.1 kkcal·mol−1). CS10 undergoes three steps of internal H-atom migration (CS10 → CS11, E = 43.3 kcal·mol−1, CS11 → CS12, E = 5.8 kcal·mol−1, CS12 → P13, E = 52.1 kcal·mol−1) to produce p-cresol. H-atom migration of CS8 produces m-cresol (CS8 → P9, E = 51.3 kcal·mol−1), and H-atom elimination of CS8 and CS32 produces m-methylphenoxy and H radical (CS8 → P31 + H, E = 69.2 kcal·mol−1, CS32 → P31 + H, E = 70.7 kcal·mol−1). CO elimination of CS6 produces methylcyclopentadiene (CS6 → P7, E = 36.5 kcal·mol−1).

Figure 1.

Potential energy surface of anisole decomposition and following reactions to produce cresols. Energies with units of kcal·mol−1 were calculated using G4 theory. Zero point energy corrections are included at 0 K.

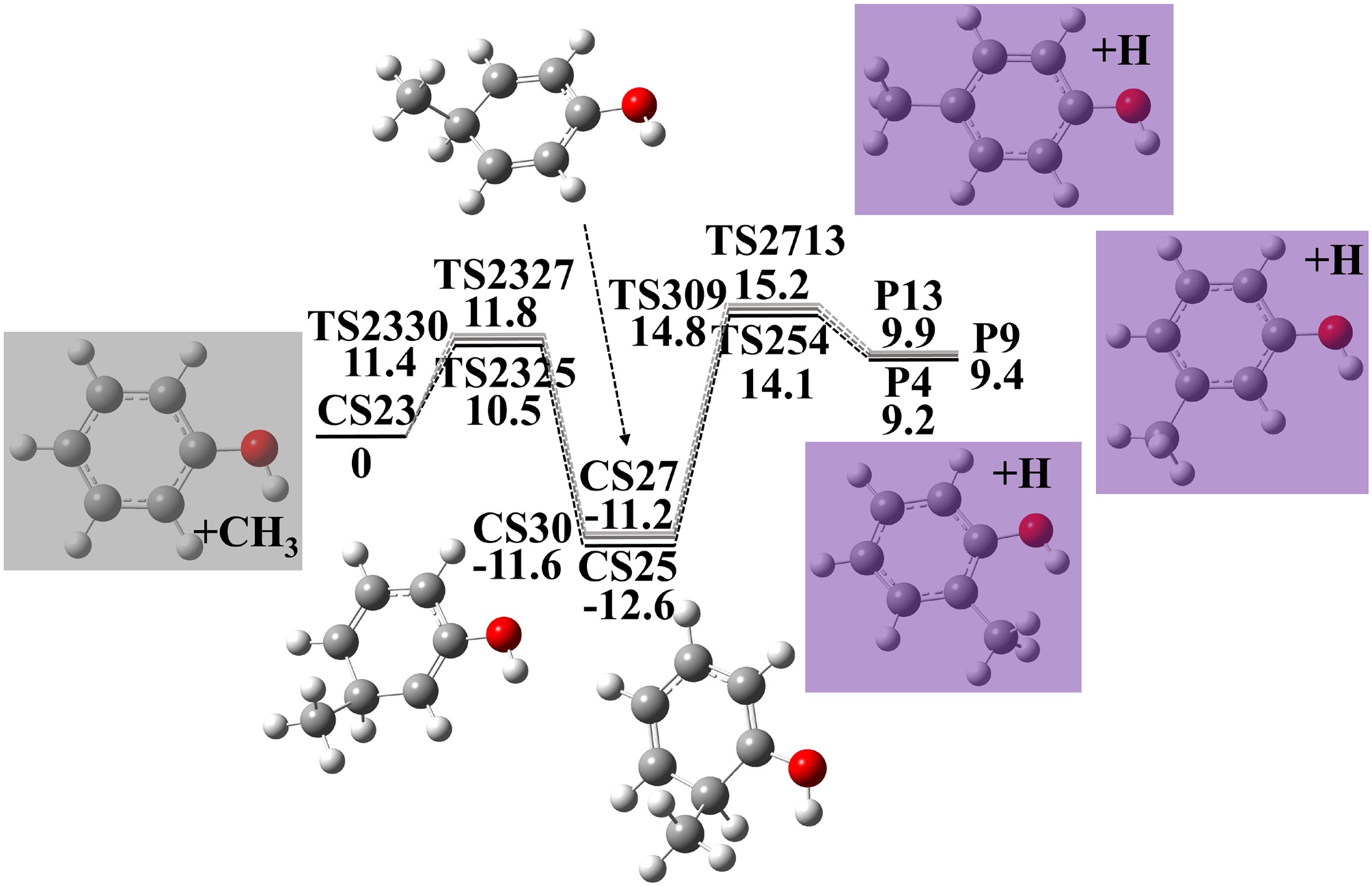

Another cresol formation pathway starts from methyl radical addition to phenol, as illustrated in Fig. 2. The methyl radical 'attacks' the ortho, meta, or para site of phenol to yield CS25, CS27, and CS30 (CS23 → CS25, E = 10.5 kcal·mol−1 CS23 → CS27, E = 11.8 kcal·mol−1, CS23 → CS30, E = 11.4 kcal·mol−1). H-atom loss of CS25, CS27, and CS30 forms o-cresol (CS25 → P4, E = 26.7 kcal·mol−1), p-cresol (CS27 → P13, E = 26.4 kcal·mol−1), and m-cresol (CS30 → P9, E = 21.0 kcal·mol−1) respectively.

Figure 2.

Potential energy surface of phenol + CH3 reactions to produce cresols. Energies with units of kcal·mol−1 were calculated using G4 theory. Zero point energy corrections are included at 0 K.

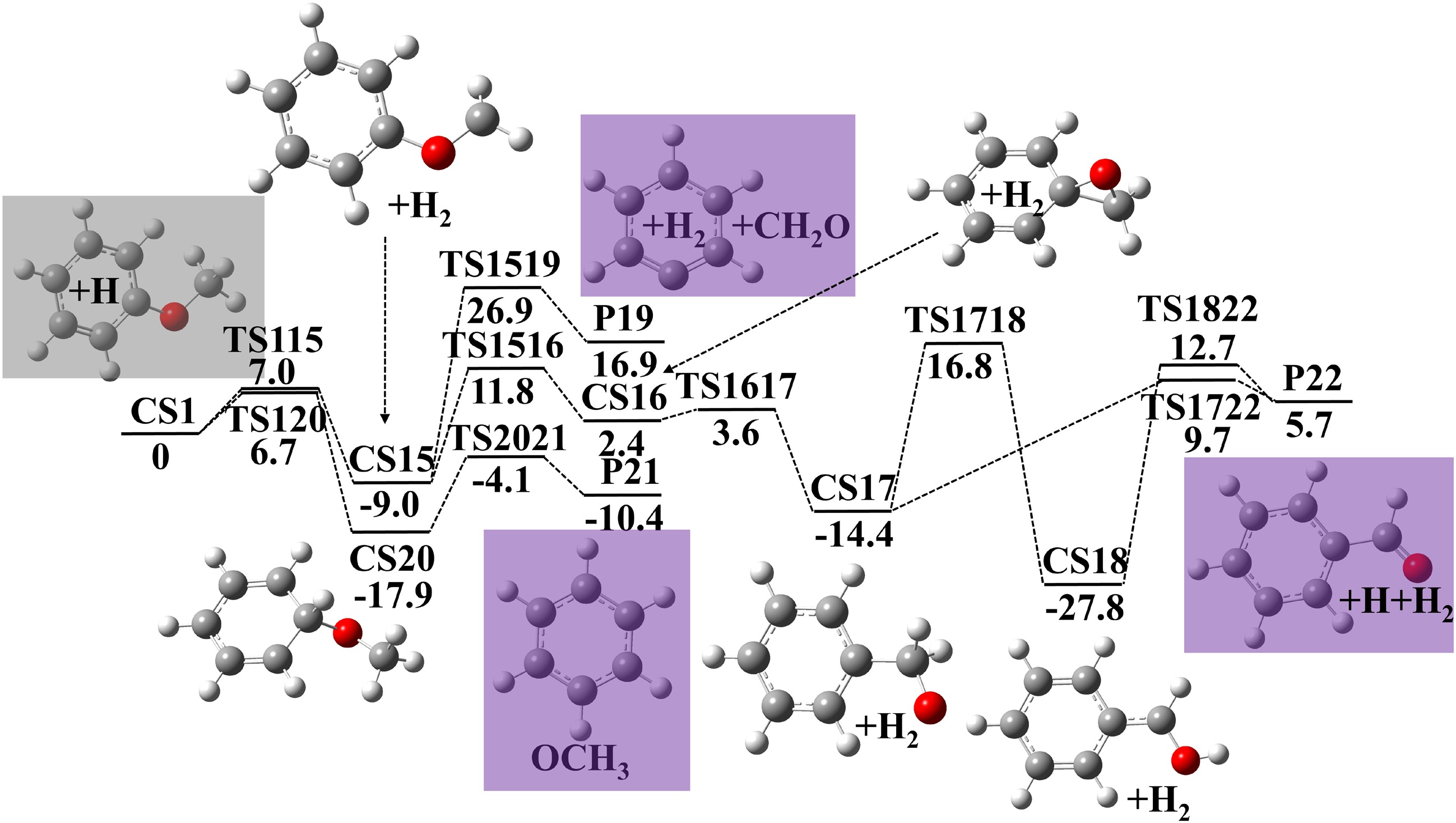

Besides the two PES, another pathway produces benzaldehyde to compete with cresol formation. The reaction pathway (presented in Fig. 3) starts from H-atom abstraction of anisole (CS1 → CS15, E = 7.0 kcal·mol−1) or H-atom addition (CS1 → CS20, E = 6.7 kcal·mol−1). CS15 have two consumption routes: CH2O elimination to produce phenyl radical (CS15 → P19, E = 35.9 kcal·mol−1), and cyclization to produce CS16 (CS15 → CS16, E = 20.8 kcal·mol−1). CS16 then undergoes three-membered ring opening (CS16 → CS17, E = 1.2 kcal·mol−1), internal H-atom migration (CS17 → CS18, E = 31.2 kcal·mol−1), and H-atom elimination to produce benzaldehyde (CS18 → P22, E = 40.5 kcal·mol−1). CS17 can also directly produce benzaldehyde (CS17 → P22 + H, E = 24.1 kcal·mol−1). For CS20, its OCH3 elimination produces benzene (CS20 → P21, E = 13.8 kcal·mol−1). The calculated rate constants of anisole + H = benzene + OCH3 in Table 1 agree with the results by Nowakowska et al.[23] within a factor of 1.5.

Figure 3.

Potential energy surface of anisole decomposition reactions initiated by H-atom abstraction and H-atom addition. Energies with units of kcal·mol−1 were calculated using G4 theory. Zero point energy corrections are included at 0 K.

Table 1. Reaction rate coefficients in the form of k = A·Tn·exp(−E/RT). The units are s−1 (k), cm3·mol−1·s−1 for bimolecular reactions and s−1 for unimolecular reactions (A) and kcal·mol−1 (E).

Reactions A n E P (atm) CS1 → P14 +CH3 1.21 × 1019 −1.452 59.48 H-P CS1 + H → P21 (benzene) + OCH3 1.05 × 108 1.511 4.984 0.1−100 P21 + OCH3 → CS1 + H 1.82 × 10−1 3.535 15.13 0.1−100 CS1 + CH3 → P24 (toluene) + OCH3 5.22 × 101 2.78 11.58 0.1−100 P24 + OCH3 → CS1 + CH3 2.52 × 10−1 3.028 4.73 0.1−100 CS1 + H → CS15 + H2 7.75 × 105 2.313 4.26 H-P CS15 + H2 → CS1 + H 3.06 × 102 2.926 11.28 H-P CS15 → P19 + CH2O 1.17 × 1056 −11.71 88.18 0.1 CS15 → P19 + CH2O 8.12 × 1033 −5.842 63.38 1 CS15 → P19 + CH2O 5.20 × 1024 −3.479 49.0 10 CS15 → P19 + CH2O 7.64 × 1018 −2.0 37.3 100 CS15 → P22 + H 1.05 × 1019 −2.024 40.52 0.1 CS15 → P22 + H 8.73 × 1032 −6.061 45.36 1 CS15 → P22 + H 3.62 × 1028 −4.999 35.82 10 CS15 → P22 + H 1.74 × 1022 −3.268 27.82 100 P14 + CH3→ P4 (through CS2) 1.90 × 1042 −8.572 14.52 H-P P14 + CH3→ P9 (through CS2) 9.81 × 1045 −10.08 21.54 H-P P14 + CH3→ P28 + H (through CS2) 4.75 × 1016 −1.704 4.56 H-P P14 + CH3→ CS3 (through CS2) 6.99 × 1099 −26.18 31.68 H-P P14 + CH3 → P13 (through CS10) 1.59 × 1053 −11.46 31.62 H-P P14 + CH3 → P7 (through CS10) 2.29 × 1031 −6.054 26.6 H-P P14 + CH3 → P9 (through CS10) 5.17 × 1061 −14.22 42.62 H-P P14 + CH3→ P29 + H (through CS10) 5.99 × 1015 −1.369 9.83 H-P P14 + CH3 → CS12 (through CS10) 1.98 × 1084 −21.68 28.74 H-P CS23 + CH3 → P4 + H 3.93 × 100 3.193 11.5 0.1−100 P4 + H → CS23 + CH3 4.05 × 108 1.343 3.52 0.1−100 CS23 + CH3 → P13 + H 1.00 × 101 3.092 13.93 0.1-100 P13 + H → CS23 + CH3 7.48 × 107 1.357 3.69 0.1−100 CS23 + CH3 → P9 + H 2.78 × 101 2.964 13.05 0.1−100 P9 + H → CS23 + CH3 3.19 × 108 1.271 4.33 0.1−100 CS8 → P31 +H 5.78 × 1014 −1.026 53.50 H-P CS32→ P31 + H 2.01 × 1016 −0.937 45.34 H-P Based on the calculated potential energy surface and species properties (energy, vibration frequencies, momentum inertia, etc.), reaction rate coefficients for each reaction in the proposed pathways are calculated and listed in Table 1. Thermodynamics for species that are not included in the LLNL model are listed in Table 2. The explored reactions, rate coefficients, thermodynamic, and transport properties of new species were implemented into the base LLNL model[8].

Table 2. Thermochemistry data of new species.

Species Formula H (298K)

(kcal·mol−1)S (298K)

(cal·K−1·mol−1)Cp

(cal·K−1·mol−1)298 K 1,000 K 2,500 K CS3 C7H8O −13.15 86.64 30.46 68.84 85.99 CS12 C7H8O −12.22 84.74 29.24 66.46 86.81 CS5 C7H8O 31.66 84.07 31.15 69.51 86.13 CS2 C7H8O −9.88 84.71 29.85 68.74 85.94 CS10 C7H8O −11.20 82.89 29.98 68.80 85.98 P4 C7H8O −29.94 82.56 30.67 68.83 85.81 P9 C7H8O −29.63 83.21 30.69 68.84 85.81 P13 C7H8O −29.13 84.83 30.82 68.85 85.81 P28 C7H7O 2.43 82.50 29.18 65.28 81.98 P29 C7H7O 3.46 84.59 29.24 65.27 80.60 Product yield analysis

-

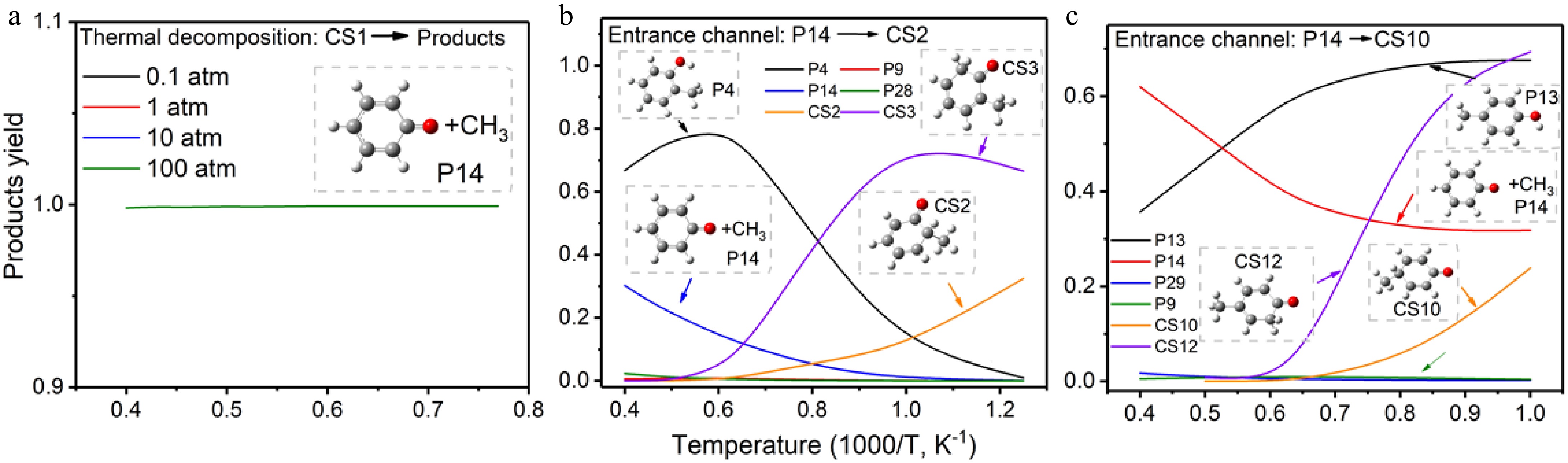

Based on potential energy surfaces and reaction rate coefficients, the reaction competition within the proposed pathway network was evaluated. As shown in Fig. 4a, almost 100% of anisole unimolecular decomposition products are phenoxy and methyl radicals (P14) under the temperature range of 700-2,500 K and pressure range of 0.1−100 atm. For reaction pathways starting from P14 → CS2, product yield analysis in Fig. 4b indicates CS3 as the favored product at temperatures below 1,200 K, while the dominant product changes to P4 at temperatures above 1,200 K. Here, P4 is o-cresol, while CS3 is the precursor of o-cresol, suggesting o-cresol as the dominant product of reaction pathways starting from CS2. Similarly, for reaction pathways starting from P14 → CS10, the product yield analysis in Fig. 4c suggests p-cresol (P13) and its precursor (CS12) as the dominant products at temperatures below 2,000 K.

Figure 4.

Product yield of (a) thermal decomposition of anisole, (b) recombination pathway with entrance reaction of CH3 + C6H5O → CS2, (c) recombination pathway with entrance reaction of CH3 + C6H5O → CS10.

Kinetic analysis

-

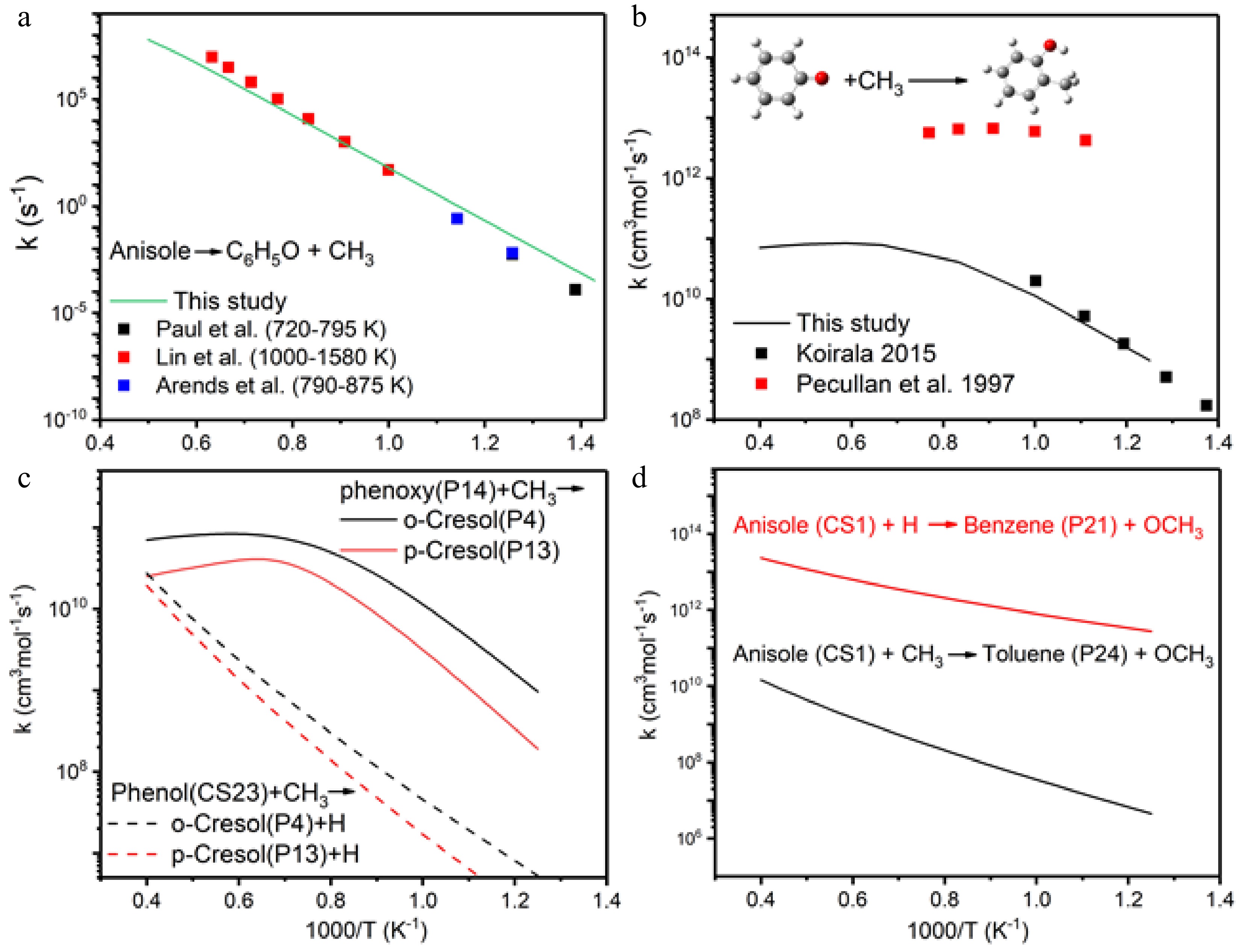

To further confirm the dominance of the aforementioned reactions and products, kinetic analysis was performed. First, the rate constants of unimolecular decomposition of anisole to phenoxy radical and methyl radical were compared with measurements in the literature, as shown in Fig. 5a. Good match between our calculations and measurements by Paul & Back[45], Lin & Lin[46], and Arends et al.[15] at different temperatures evidenced the accuracy of calculated rate constants. For methyl radical addition to phenoxy radicals, calculated rate constants match with the results from Koirala's PhD thesis[32], but with large discrepancies with the data by Pecullan et al.[17]. Considering the timeliness of reaction rate measurements, we believe the data from Koirala are more accurate.

Figure 5.

Reaction rate coefficients of (a) thermal decomposition of anisole, (b) o-cresol formation, (c) comparison of o-cresol and p-cresol formation, (d) OCH3 elimination followed by H/CH3 addition.

Now we compare the reaction rate constants of methyl radical addition to phenoxy radical or phenol, where both pathways lead to o-cresol and p-cresol formation. From Fig. 5c, the rate constants of methyl radical and phenoxy radical recombination are much higher than those of methyl radical addition to phenol at temperatures below 2,500 K, which is not surprising due to the rapid radical-radical recombination. Rate constant comparison also indicates o-cresol formation is faster than that of p-cresol, which is further evidenced by experiments in the following section. The ipso-substitution of H-atom with OCH3 elimination is much faster than CH3 ipso-substitution, as shown in Fig. 5d.

-

Here, the proposed cresol formation chemistry is examined by comparing experiments and kinetic model simulations. Since the target is to examine predictions for cresol isomers without influencing the good prediction capability for reactants, main products, and other important intermediate species, only speciation data that include cresol (lumped or de-lumped) are chosen as validation targets[8,23,28]. The changes caused by reaction pathway implementation are compared and highlighted. In Figs 6−9, the scatter points indicate measured data with shaded areas as experimental uncertainty, which was reported in the literature[8,23,28]. The solid lines refer to simulations using the model after pathway implementation, while the dashed lines are those using the base LLNL model.

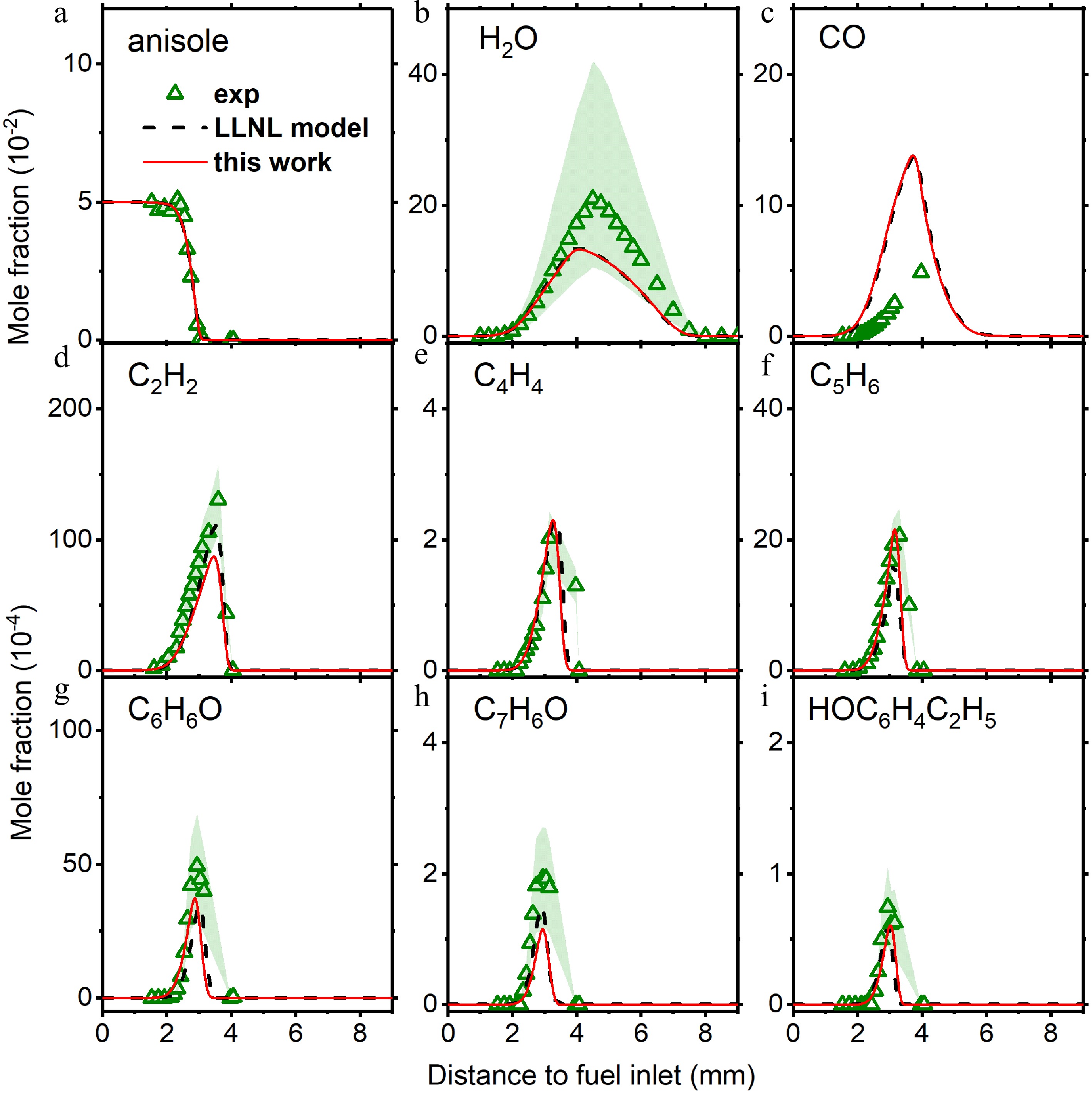

Figure 7.

Mole fraction profiles of reactants, main products, and important intermediate species in anisole counterflow diffusion flame. Experimental data are taken from Chen et al.[28]. The solid lines are simulation using the model with the isomer-specific cresol formation pathways, compare to the dashed lines using the LLNL model[8].

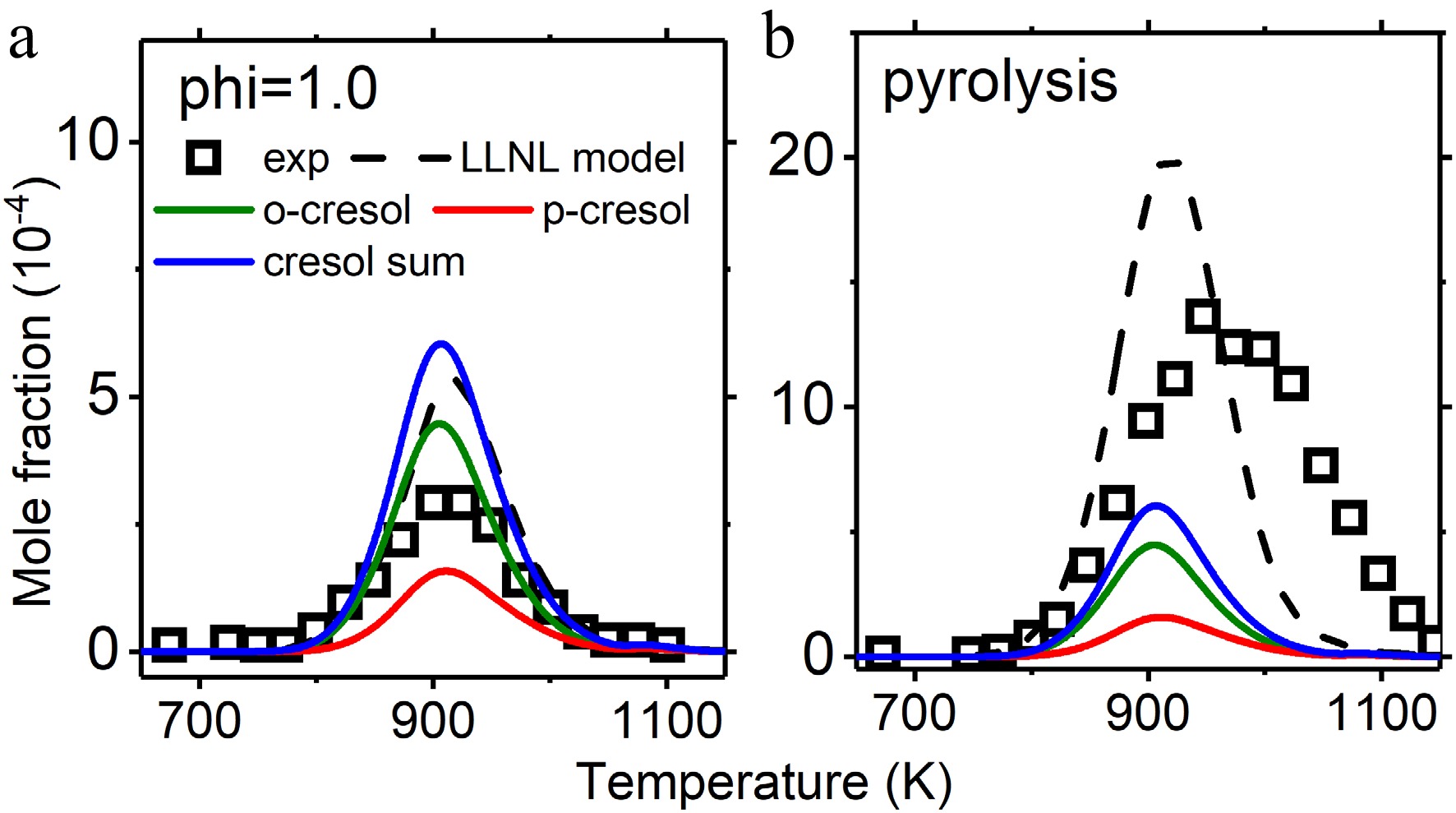

Figure 8.

Mole fraction profiles of cresol in jet stirred reactor oxidation and pyrolysis. Experimental data are taken from Nowakowska et al.[23]. The solid lines are simulations using the model with the isomer-specific cresol formation pathways, compared to the dashed lines using the LLNL model[8].

Speciation in counterflow diffusion flame

-

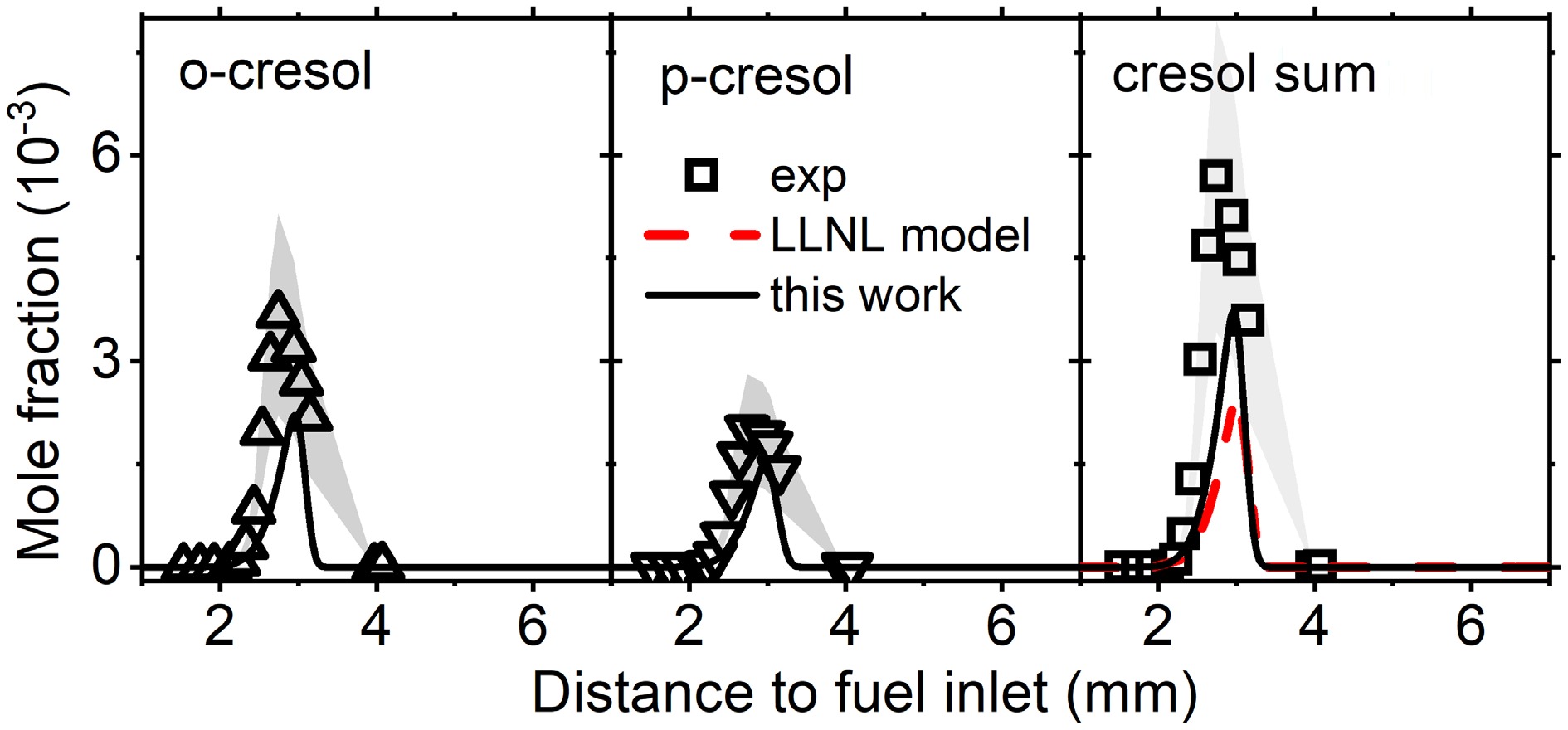

Cresol formation is first examined in the anisole counterflow diffusion flame, where two cresol isomers, o-cresol and p-cresol, were separated and measured, while m-cresol was not detected[28]. Figure 6 presents the mole fractions of cresol isomers vs distance to fuel inlet. It can be observed that the cresol formation pathways accurately captured the measured mole fractions of o-cresol and p-cresol, while cresol isomers were lumped and underpredicted by the LLNL model. Another finding is that the maximum mole fractions of o-cresol are higher than those of p-cresol from both experiments and simulations. This supports the observation in kinetic analysis that the rate constants of o-cresol formation are higher than those of p-cresol.

The reaction pathway implementation does not influence the predictions of other species. Figure 7 compares the species mole fractions using both models. It can be found that for reactants (anisole and oxygen), main products (water and carbon monoxide), small intermediates (acetylene, vinylacetylene, and cyclopentadiene), and large aromatic intermediates (phenol, benzaldehyde, and ethyl-phenol), their calculated mole fractions do not change much after reaction pathway implementation.

Speciation in a jet stirred reactor

-

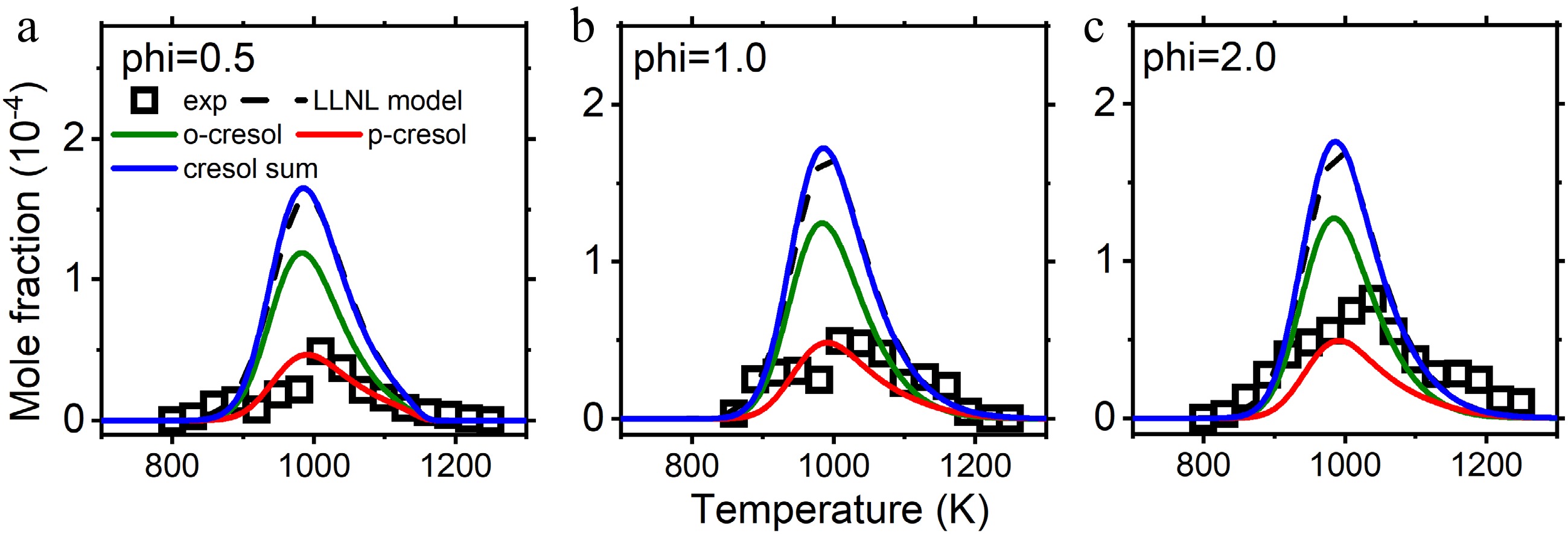

Further model validation is performed for anisole pyrolysis and oxidation in a jet stirred reactor. Figures 8 and 9 compare the mole fractions of cresol isomers by experiments and kinetic model simulation. Since the simulated mole fractions of m-cresol are much lower, they are not included and discussed. The experimental data were taken from Nowakowska et al.[23] and Wagnon et al.[8]. The explored cresol formation chemistry in this work separated p-cresol and o-cresol, while experiments and the LLNL model lumped the cresol isomers. It can be observed that implementation of cresol formation pathways can capture the measured cresol mole fractions, with some overpredictions in stoichiometric oxidation and underpredictions in pyrolysis. Good predictions for reactants, main products, and other important intermediate species are not interfered with by cresol formation pathway implementation, as shown in Supplementary Figs S3−S7.

-

As important secondary organic aerosol precursors, the formation chemistry of cresol isomers from anisole are systematically investigated. Quantum chemistry using the high-level G4 method was used for reaction pathway exploration. Two cresol formation pathways, methyl radical addition to phenoxy radical, and methyl radical addition to phenol, are proposed with unimolecular decomposition of anisole as initiation reactions. Product yield analysis indicates that recombination of methyl radical and phenoxy radical is the dominant pathway for o-cresol, m-cresol, and p-cresol formation. Rate constant comparison highlights the higher rate constants of o-cresol formation than those of p-cresol. The proposed reaction pathways were validated by model development and experiments, proven by their capability to best capture the measured mole fractions of cresol isomers, reactants, main products, and important intermediate species in both counterflow diffusion flame and jet stirred reactor. The unraveled cresol formation chemistry may help develop a reaction control strategy for clean and efficient biomass combustion process.

This work was supported by the financial support of National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFC3701500), and the National Natural Science Foundation (52406160, 22503055).

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Chen B, Liu P; data collection: Chen B, Liu P, Zhang X; analysis and interpretation of results: Chen B, Wu Z, Lyu H; draft manuscript preparation: Chen B, Liu P. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The calculated potential energy surface, reaction rate coefficients, and species thermodynamics are available within the article. The model files (kinetic, thermodynamic, transport) are provided in the Supplementary Information files. The experimental data are collected in published papers and their supplementary files[8,23,28].

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary File 1 The kineticmodel files.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Bond scan to ensure the correct transition state.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Pressure dependence of o-cresol formation from methyl radical addition to phenoxy radical.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 Mole fraction profiles of reactants, main products, and important intermediate species of anisole pyrolysis in jet stirred reactor.

- Supplementary Fig. S4 Mole fraction profiles of reactants, main products, and important intermediate species of anisole oxidation (phi = 1.0) in jet stirred reactor.

- Supplementary Fig. S5 Mole fraction profiles of reactants, main products, and important intermediate species of anisole oxidation (phi = 0.5) in jet stirred reactor.

- Supplementary Fig. S6 Mole fraction profiles of reactants, main products, and important intermediate species of anisole oxidation (phi = 1.0) in jet stirred reactor.

- Supplementary Fig. S7 Mole fraction profiles of reactants, main products, and important intermediate species of anisole oxidation (phi = 2.0) in jet stirred reactor.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Chen B, Wu Z, Zhang X, Lyu H, Liu P. 2025. Cresol formation chemistry in anisole pyrolysis and combustion. Progress in Reaction Kinetics and Mechanism 50: e021 doi: 10.48130/prkm-0025-0021

Cresol formation chemistry in anisole pyrolysis and combustion

- Received: 15 April 2025

- Revised: 01 September 2025

- Accepted: 15 September 2025

- Published online: 03 November 2025

Abstract: Biomass combustion is a promising energy source with a low carbon footprint. However, the large number of benzyloxy functional groups in the biomass molecular structure may increase cresol emission as oxygenated aromatic precursors for secondary organic aerosol and oxygenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Understanding the formation chemistry of cresols can aid in developing effective emission control strategies. In this work, the reaction pathways to produce cresol isomers (o-cresol, m-cresol, and p-cresol) from anisole, a representative surrogate for lignin were investigated. Important potential energy surfaces, reaction rate coefficients, and species thermodynamics were calculated by quantum chemistry using the G4 method. Results indicate that cresol isomers are mainly produced by the recombination of methyl radicals with phenoxy radicals or phenol. Alternatively, isomerization of anisyl radical from H-atom abstraction of anisole produces benzaldehyde as a competing pathway. The explored reaction pathways were then implemented into the LLNL model to examine the prediction of cresol isomer yields with experimental data in various reactors. Instead of developing a new kinetic model, this work aims to provide insights into cresol formation chemistry to support the development of reaction control strategies for clean and efficient biomass utilization.

-

Key words:

- Cresols /

- Anisole /

- Pollutant formation chemistry /

- Biomass /

- Oxygenated aromatics