-

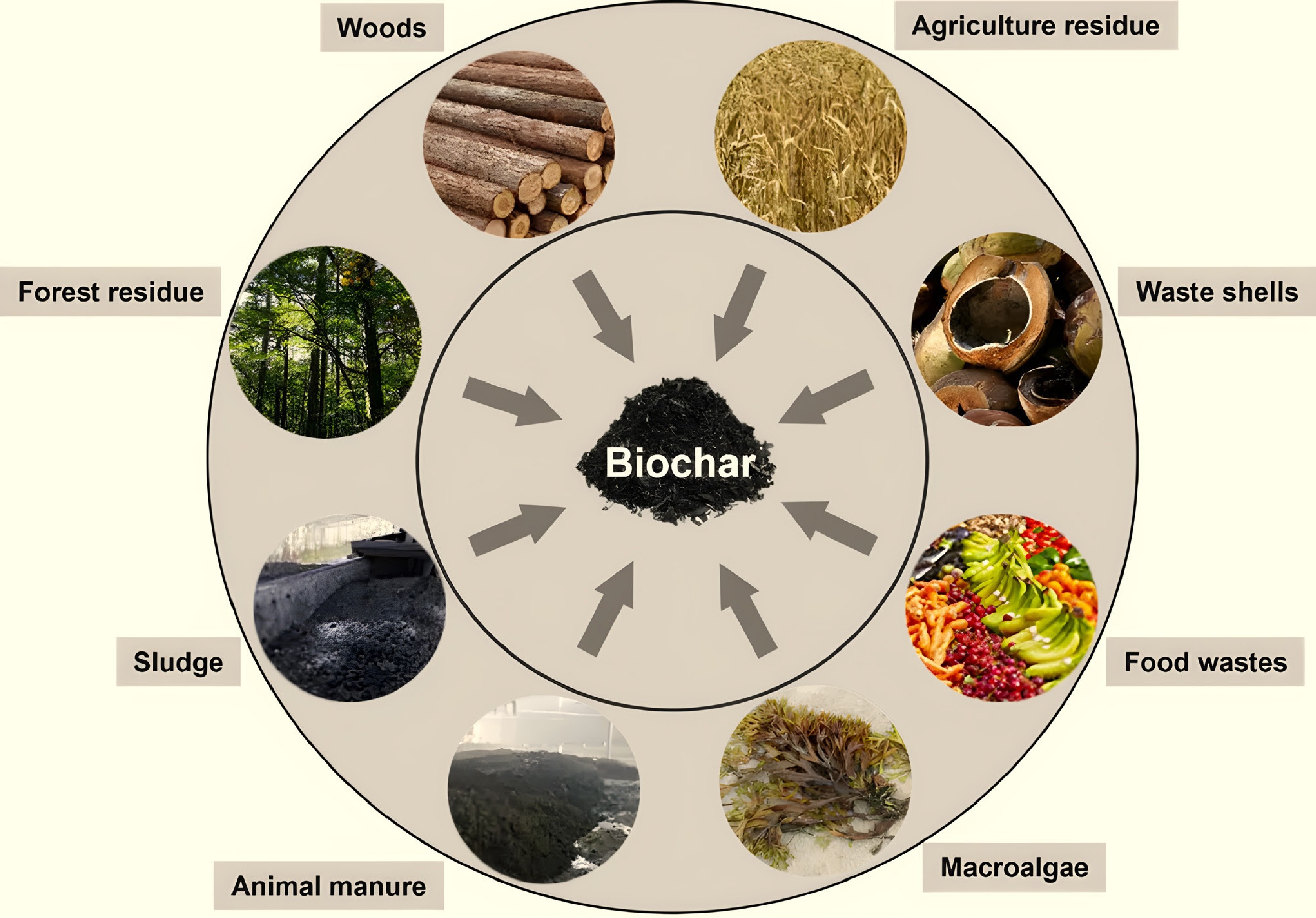

Biochar is a carbonaceous material produced by pyrolyzing biomass in an oxygen-limited atmosphere[1]. Typical feedstocks for biochar production include agricultural waste, forestry residues, municipal sludge, and animal manure (Fig. 1)[2]. Biochar is gaining increasing attention in environmental remediation due to its advantages of a large specific surface area, high adsorption performance, and low cost[3]. As a multifunctional material, biochar has become an increasingly prominent research focus in various disciplines due to its low-cost advantage and beneficial carbon sequestration and environmental applications[4]. Biochar is utilized extensively for its benefits, including reducing nutrient leaching from the soil, improving soil conditions, and facilitating carbon sequestration. It is also used to remove organic pollutants, such as fungicides, herbicides, and other pesticides, from the soil[5]. Various agricultural residues can be utilized as feedstocks for biochar production, including crop residues (e.g., straw, husks, shells), wood products, animal manure, and dairy byproducts[6−10]. The type of feedstocks used and the pyrolysis conditions play essential roles in determining the physical and chemical properties of the produced biochar[11]. Biochar exhibits sorption properties, making it an alternative medium for immobilizing organic pollutants and heavy metals from wastewater, sewage, and aqueous media[12]. However, the physico-chemical characteristics of pristine biochar are heterogeneous, including surface area, porosity, chemical functionality, and surface charge, and vary with feedstock and pyrolysis conditions. Consequently, the adsorption capacity of pristine biochar for pollutants is relatively low. In this regard, various methods are employed to modify biochar, thereby improving its physicochemical properties, such as surface area, functionality, and pore structure, and enhancing its ability to remove contaminants efficiently[13]. Therefore, the development of low-cost, high-efficiency, and environmentally friendly functionalized biochar is of great importance for improving pollution control, with recent attention focusing on increasing sorption sites and functional groups through functionalization.

Biochar modification involving various methods such as acid treatment, alkali treatment, amination, surfactant modification, mineral adsorbent impregnation, steam activation, and magnetic modification has been extensively studied[14]. These methods can be categorized into three main groups: chemical modification, physical modification, and biological modification[15]. Iron mineral-loaded biochar has emerged as a popular modification in recent years. Iron-modified biochar enhances contaminant adsorption by increasing surface charge, introducing hydroxyl groups, and providing active sites from iron oxides (e.g., hematite, goethite), while also imparting magnetic properties that facilitate reuse and recycling[16,17]. According to Diao et al.[18], when peroxymonosulfate (PMS) was activated to remove atrazine from soil using a novel biochar-supported zero-valent iron (BC-nZVI), about 96% of atrazine was removed. Another study found that Fe-phenol-modified biochar removed 94% of atrazine in 30 min at pH 8[19]. In conclusion, the advancement of biochar modification techniques, particularly iron-modified biochar, demonstrates significant potential for environmental remediation. Continued research and development in biochar modifications could lead to broader water and soil treatment applications, supporting environmental sustainability efforts.

This review significantly advances the discussion on iron-modified biochar by systematically exploring iron–carbon (Fe–C) interactions across environmental and energy applications, moving beyond conventional biochar reviews. It delves into iron functionalization methods—including in situ pyrolysis, post-treatment impregnation, and emerging techniques—and elucidates the synergistic roles of Fe species and carbon matrices in enhancing adsorption, redox reactivity, and electron transfer. Critically, the review highlights persistent research gaps such as the insufficient mechanistic understanding of contaminant interactions, the lack of standardized evaluation protocols, and limited field-scale validation. It further identifies future priorities, including lifecycle assessments, multifunctional hybrid composites, circular bioeconomy integration, and novel 'smart' biochar applications for sensing and controlled remediation. By addressing these understudied areas, this work provides a comprehensive and forward-looking perspective that distinguishes it from earlier reviews and guides future research toward scalable, sustainable, and mechanism-driven applications of Fe-biochar.

-

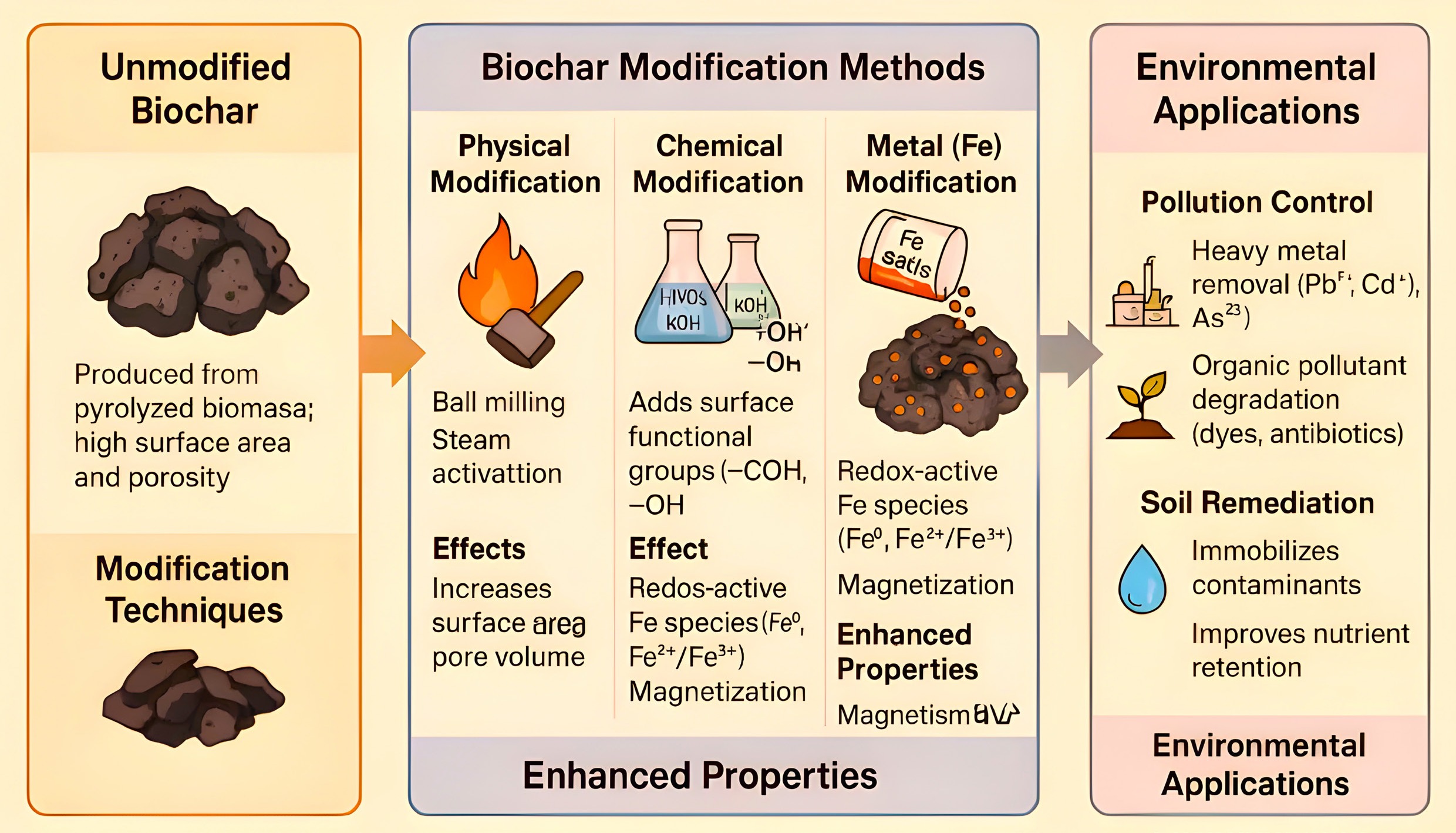

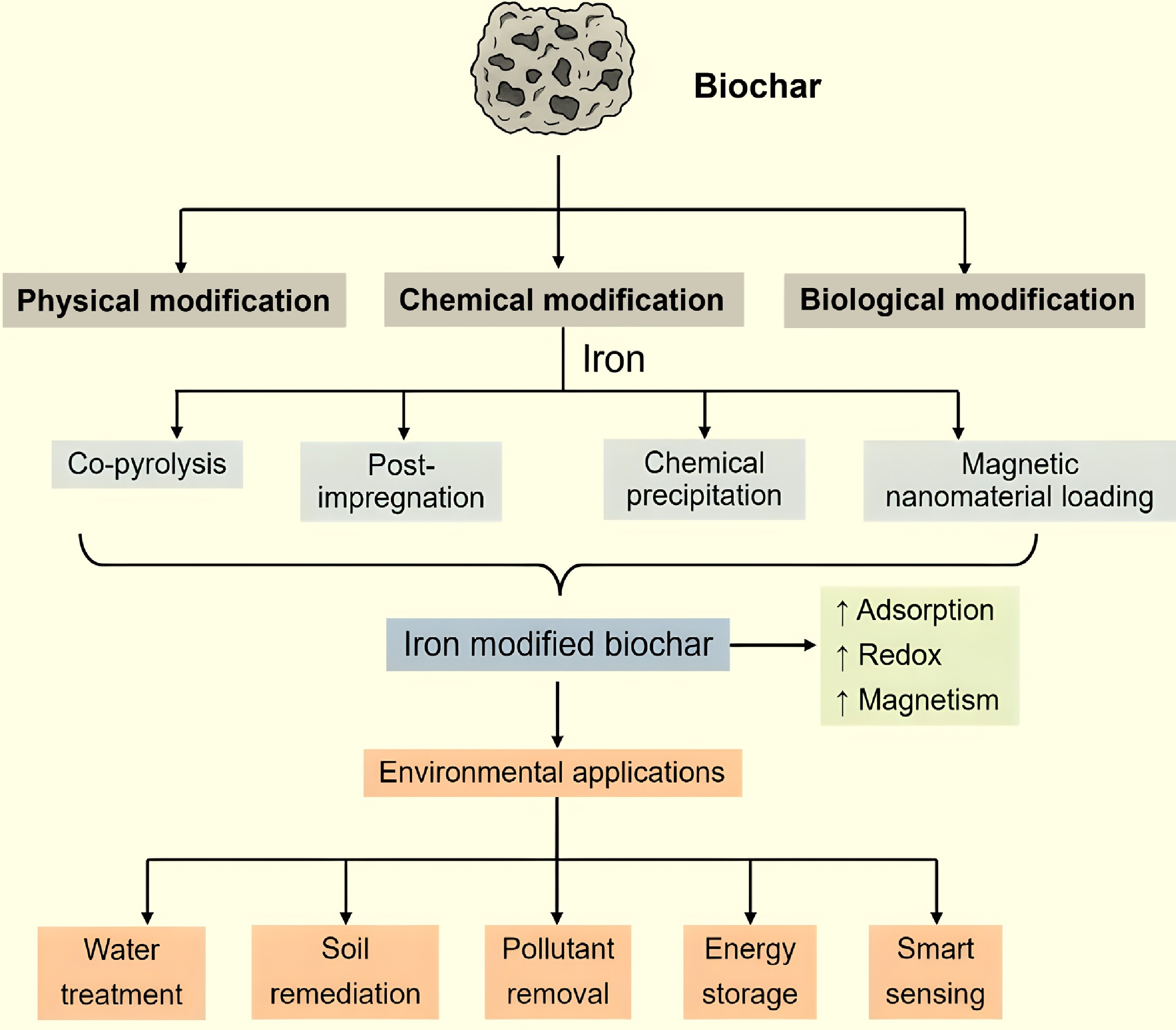

Biochar modification methods have garnered significant attention in recent years due to their potential to enhance the physicochemical properties of biochar for various environmental and agricultural applications. Unmodified biochar often has limitations such as low surface area, limited porosity, and inadequate active functional groups, which can restrict its effectiveness in adsorption, nutrient retention, or catalysis. Several modification techniques have been developed to address these issues, broadly categorized into physical, chemical, and biological methods. Physical modifications include steam activation, heat treatment, and ball milling to increase porosity and surface area[20]. Chemical modifications involve the use of acids (e.g., HNO3, H2SO4), bases (e.g., NaOH, KOH), oxidizing agents (e.g., H2O2), or metal impregnation (e.g., Fe, Mn, Zn) to enhance surface functionality and ion exchange capacity[21,22]. Biological methods utilize microbial treatments to introduce specific functional groups or biofilm layers that can aid in biodegradation or nutrient transformation[23]. These tailored modifications significantly improve the biochar's adsorption capacity for heavy metals, nutrients, and organic pollutants, making it a versatile material for soil remediation, water treatment, and carbon sequestration. Overall, the choice of modification method depends on the intended application and the source material used for biochar production. A comprehensive summary of biochar modification methods and iron-functionalized biochar is provided in Fig. 2 and Table 1.

Figure 2.

Preparation, modification methods, and environmental applications of iron-modified biochar.

Table 1. Biochar modification methods and iron-modified biochar

Modification method Description Key feature Target contaminant/

applicationRef. Physical activation Steam, CO2, N2, or air at high temperatures activate biochar Increases surface area and porosity Adsorption of dyes, heavy metals [24] Ball milling Utilizes the kinetic energy of moving balls to alter particle morphology Improves specific surface area, pore volume, and functional groups Heavy metals, PFAS removal [25,26] Gas filling Introduces oxidizing gases to react with carbon in biochar Increases surface area, micropore area, micropore capacity, and formation of surface oxides Heavy metals removal [27] Steam Thermal treatment without oxygen, reacts with carbon to form CO and H2 Enhances mesopore structures at higher temperatures, while reducing micropore structure Heavy metals, tetracycline, sulfamethazine removal [13,28] Chemical activation Uses activating agents like KOH, H3PO4, or ZnCl2 Enhances functional groups and pore structure Pollutant removal, energy storage [29] Acid Treatment with hydrochloric, sulfuric, nitric, phosphoric, oxalic, or citric acid effectively removes metallic impurities while introducing acidic functional groups Increases the acidic functional groups and improving the pore structure to provide more cation exchange active sites Heavy metals removal, prepare biochar-based fertilizers, improvement of saline-alkali soil [30−33] Alkali Common alkaline agents include potassium hydroxide and sodium hydroxide. Increases the number of functional groups, improve the specific surface area and pore volume, provide better anion attachment sites Heavy metals, antibiotics, VOCs removal [34,35] Oxidizer Use oxidizing-agents like H2O2 or KMnO4 Provides additional redox potential by increasing the number of oxygen-containing functional groups Soil amendment, heavy metals, organic pollutants removal [29,36,37] Metal salts Pyrolyzed together with the feedstock, or treating pre-formed biochar under specific conditions. Form the porous structure, oxygen-containing functional groups, catalytic capacity, recycled biochar Heavy metals, dyes, antibiotics removal [30,38−40] Iron impregnation Post-pyrolysis treatment with FeCl3, Fe(NO3)3, or FeSO4 solutions Introduction of Fe species for redox activity Heavy metals, phosphate, arsenic [41,42] Co-pyrolysis with iron Biomass and iron precursors are pyrolyzed together Strong interaction between Fe and the carbon matrix Enhanced stability and adsorption [43] Precipitation method Iron salts precipitated onto the biochar surface Uniform Fe distribution, nano-Fe formation Nitrate, antibiotics, organics [44] Magnetic modification Embeds magnetite or maghemite (Fe3O4/γ-Fe2O3) nanoparticles Magnetic recovery, reusable sorbents Magnetic separation, water treatment [45] Hybrid composite Blending Fe-biochar with zeolite, silica, graphene, or polymers Multifunctionality and synergistic remediation effects Emerging pollutants, multi-contaminant sites [46,47] Nano-iron functionalization Biochar functionalized with zero-valent iron (nZVI) Enhanced reactivity, Fenton-like activity Organic pollutants, Cr(VI), pesticides [16,48] Red mud incorporation Utilizes industrial waste (iron-rich red mud) as Fe source Sustainable, cost-effective approach Soil remediation, acid mine drainage [49] Smart biochar sensor systems Iron-biochar integrated with sensing agents or responsive materials Environmental sensing and contaminant detection Real-time monitoring, innovative remediation [14] Chemical modification

-

Currently, chemical techniques are one of the most used modification methods. They usually include modification with acids, bases, oxidizing agents, metal salts or metal oxides, and organic reagents. Acid modification can enhance adsorption efficiency by increasing acidic functional groups and improving the pore structure, thereby providing more active sites for cation exchange. However, the use of strong acids may adversely affect the pore structure. Additionally, acid modification can alter the specific surface area of biochar, with the extent of this alteration depending on the type and concentration of the acid used[30,50,51]. Alkali modification can enhance the number of functional groups on the surface of biochar, increase its specific surface area and pore volume, and provide more attachment sites for anions, thereby enhancing the adsorption of pollutants[52−54]. Oxidant modification can increase the quantity of oxygen-containing functional groups on biochar. Biochar modified with H2O2 or KMnO4 exhibits higher contaminant adsorption capacity than pristine biochar[55,56].

Modification with metal salts or metal oxides can change biochar's adsorption, catalytic, and magnetic properties. The biochar surface is typically negatively charged and exhibits low adsorption capacity for anionic contaminants. Metal modification can alter the surface properties of biochar, thereby increasing its adsorption capacity for anionic pollutants. Additionally, metal salt modification can load metals onto biochar, enhancing its adsorption capacity and imparting catalytic properties. Moreover, due to the small particle size of biochar, recovering it from water used for pollutant removal is challenging. Modification with iron salts or iron oxides can enhance the magnetic properties of biochar, facilitating its recovery and recycling. For instance, combining biochar with magnetic adsorbents, such as magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles or zero-valent iron, imparts magnetic properties to the biochar. This modification facilitates the recycling of biochar and enhances its adsorption capacity for heavy metals[57,58].

Two methods were employed to modify biochar using metal salts or metal oxides. The first method involves mixing metal salts or metal oxides with the feedstock, followed by pyrolysis to produce biochar. The second method entails first pyrolyzing the feedstock to prepare biochar, which is then impregnated with metal ions or metal oxides under specific conditions[41,59−61]. Common metals used include iron, manganese, magnesium, and aluminum. Several studies have indicated that iron-modified biochar exhibits the highest efficiency in contaminant degradation. The superior performance of iron-modified biochar can be attributed to the presence of iron particles on the biochar surface, as demonstrated by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) analysis[62]. Jiang et al.[47] reported a contaminant degradation efficiency of 73.47% when using a composite of zero-valent iron and biochar (ZVI/BC) for activation. The enhanced catalytic reactivity of Fe-loaded biochar is likely due to the increased density of active sites available for activation, which facilitates more efficient electron transfer[63].

Physical modification

-

Physical biochar modification methods generally include ball milling modification, steam activation, and gasification. The primary aim of these methods is to change the surface properties and porous structure of biochar.

Lately, ball milling has received increasing attention as an approach to manufacturing advanced nano-materials due to its high efficiency and eco-friendly features[48]. The high-speed moving spheres in the ball mill mechanically reduce the particle size of biochar to the micro- or nano-range, thus increasing the surface area and homogeneity of biochar. Ball milling application technology is favored by researchers for its affordability and reproducibility[64]. It is recognized that ball milling can improve biochar's functional characteristics and specific surface area, thus improving its sorption ability to various pollutants.

Modification with gases such as steam, oxygen, or carbon dioxide has proven effective in increasing the surface area and pore volume of biochar, while also forming active sites on its surface. The gas modification process typically occurs at temperatures above 700 °C and requires small amounts of steam and oxygen; however, biochar yield is lower than that from conventional pyrolysis. The advantages of gas modification include its environmental friendliness and the absence of secondary pollution. However, the method's high temperature and energy requirements, along with a relatively low carbon yield, limit its widespread application[65−67].

Biological modification

-

Biological modification primarily involves utilizing biological resources, such as microorganisms or plants, to modify biochar. For instance, microorganisms can be introduced and cultivated on the surface of biochar. Typically, microbial residual biomass, including bacteria, algae, fungi, and yeasts, can effectively accumulate heavy metals. Additionally, these microorganisms can enhance the adsorption and biodegradation of both organic and inorganic materials[68−70]. Currently, the use of this type of method is relatively low compared to other modification methods. The main reason for this is the complexity and duration of the modification process using microorganisms or plants.

-

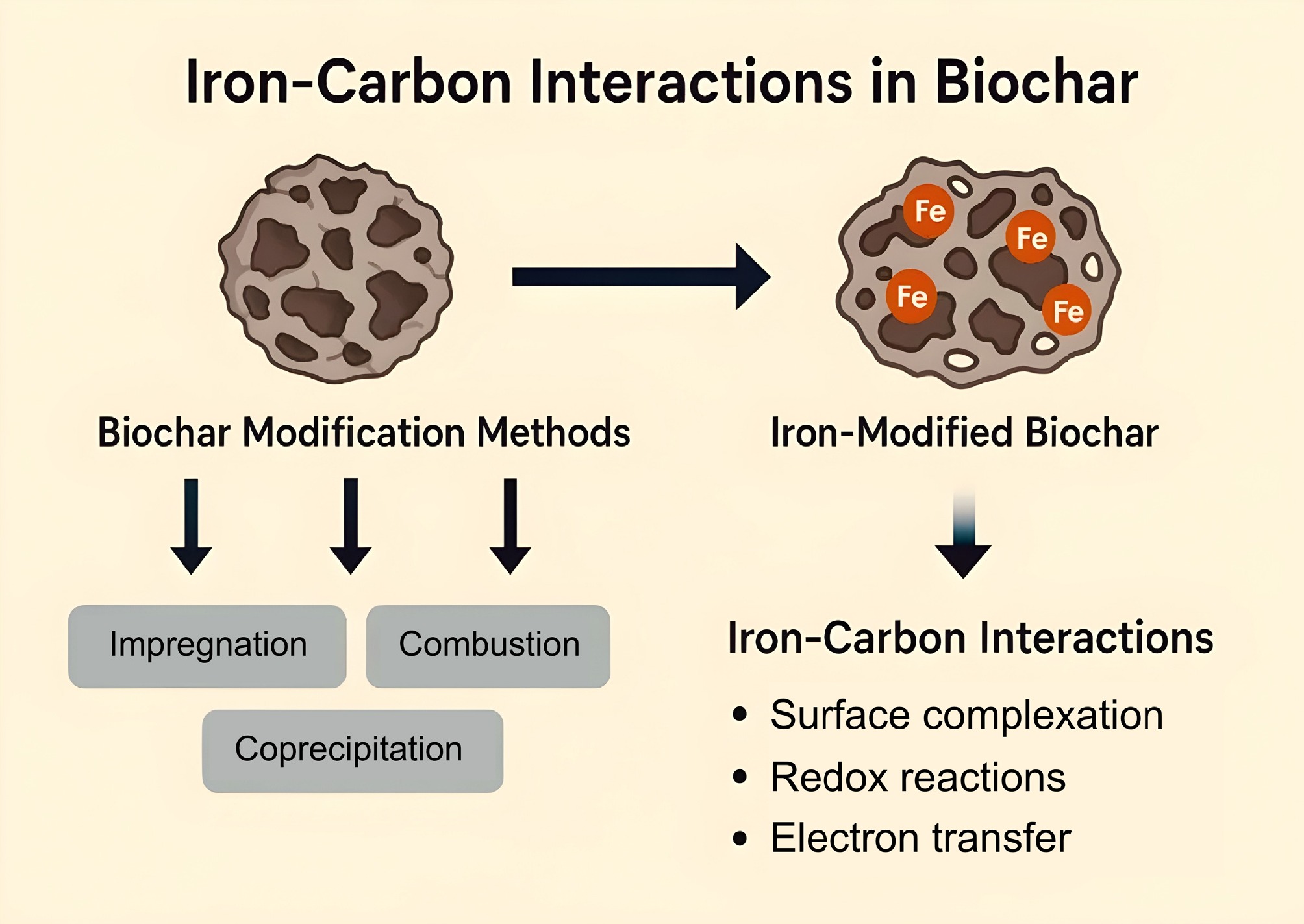

The modification of biochar with iron (Fe) represents a crucial research frontier in environmental remediation, carbon sequestration, and nutrient recovery. Biochar, a carbon-rich material produced through the pyrolysis of biomass, is highly valued for its porous structure, high surface area, and diverse functional groups. However, pristine biochar often exhibits limited reactivity toward specific contaminants. To enhance its physicochemical performance, especially for applications such as heavy metal adsorption, phosphate immobilization, and redox-based pollutant degradation, researchers have increasingly focused on iron modification strategies. Iron-carbon (Fe–C) interactions within modified biochar systems are critical in driving sorption, catalytic, and electron transfer mechanisms (Table 1, Fig. 3).

Biochar modification methods for iron functionalization

-

Iron-loaded biochar composites are typically synthesized using four primary methods: hybrid pyrolysis of precursors, chemical precipitation, the hydrothermal process, and ball milling[42]. The precursor-mixing pyrolysis method primarily involves the incorporation of metal ions into the biomass before pyrolysis. In this process, the biomass feedstock is impregnated with a solution of divalent or trivalent iron salts, allowing Fe ions to be introduced onto the surface or into the interior of the biomass precursor. In the in situ method, iron salts such as FeCl3, Fe(NO3)3, or FeSO4 are mixed with biomass feedstocks (e.g., sawdust, rice husk, sewage sludge) before pyrolysis, enabling the formation of Fe3O4, Fe2O3, or Fe0 nanoparticles within the biochar matrix during thermal treatment[71]. During pyrolysis, these Fe ions are subsequently converted in situ to iron oxides through interactions with reducing agents produced during the thermal decomposition of the biomass[72]. Post-pyrolysis modification involves impregnating pre-formed biochar with iron solutions, followed by thermal or chemical treatment, which facilitates the deposition of iron oxide or zero-valent iron (ZVI) on the biochar surface[20].

Furthermore, the process of immersing biochar in a solution containing metal ions and introducing a chemical reagent to induce the precipitation of metal ions onto the biochar surface is referred to as chemical precipitation[73]. In addition, the hydrothermal method involves the crystallization and uniform dispersion of iron oxides on the surface or within the biochar under high temperature and pressure, using water or other solvents as the reaction medium[74]. The ball milling method enhances the adsorption properties of biochar and iron oxides by applying mechanical external forces. This process induces structural defects, reduces the size of solid particles to the nanoscale, generates accelerated bond-breaking energy, and facilitates the formation of free radicals through various mechanisms[75,76]. Emerging modification techniques include hydrothermal synthesis, sol–gel processes, and microwave-assisted impregnation, which allow for better control over nanoparticle distribution and oxidation states of iron. These methods can tailor the pore size distribution, surface charge, and redox activity of biochar, enhancing its environmental functionality[77]. Table 2 provides a comparative overview of biochar modification techniques, highlighting iron-based modification's enhanced efficacy and benefits.

Table 2. The advantages of iron modification compared with other modification methods

Feature Iron-modified biochar Acid/alkali-modified biochar Physical modification Other metal modifications (e.g., Mg, Al, Zn) Magnetic separation Excellent, enables easy recovery None None Usually none (unless with magnetic metals) Adsorption of anions (e.g., As, Cr, F) Very strong (specific adsorption + reduction for Cr) Alkali-modification improves it, but weaker and non-specific Moderate (mainly physisorption) Strong (e.g., Al-modified for As, Mg-modified for P) Adsorption of cations (e.g., Pb2+, Cd2+) Good Excellent (acid-modification increases surface O-groups) Good Excellent (e.g., Mg-modified

for Cd)Treatment of organic pollutants Adsorption + catalytic degradation Adsorption (may be enhanced

via porosity)Adsorption (high surface area) Adsorption (some may have catalytic properties) Primary function Adsorption, reduction, catalysis, magnetism Enhancement of ion exchange/

electrostatic adsorptionCreation of porous structure Enhancement of specific adsorption/complexation Application cost Low Low to moderate Moderate (high temperature

& energy)Moderate to high

(depends on metal salt)Key application field Wastewater (As/Cr removal, organic degradation), soil remediation Adjustment of adsorption for cations/anions General-purpose adsorbent, energy storage Targeted pollutant removal (e.g., P, F) Ref. [78−81] [82−85] [86−89] [90−92] Mechanistic role of iron–carbon interactions

-

Iron-modified biochar (Fe–BC) demonstrates distinctive Fe–C synergisms that extend its role from a passive sorbent to an active redox mediator. The incorporated iron species serve as electron donors or acceptors, thereby enhancing the transformation of contaminants such as Cr(VI), As(III), and various organic pollutants through Fenton-like reactions[93]. In the case of Cr(VI) removal, multiple synergistic mechanisms operate concurrently. Initially, electrostatic attraction between negatively charged Cr(VI) species (e.g., CrO42−, HCrO4−) and the positively charged surface of Fe–BC promotes adsorption. Reduction then becomes the dominant pathway, whereby Fe(II) in FeO and redox-active functional groups (e.g., hydroxyl and carbonyl moieties) donate electrons to convert toxic Cr(VI) into the less harmful Cr(III). The resulting Cr(III) is subsequently stabilized through complexation with oxygen-containing functional groups on the biochar surface or through co-precipitation with iron species, forming insoluble compounds such as FeCr2O4 and Cr2O3. Collectively, these processes—adsorption, reduction, complexation, and precipitation—act in concert to ensure effective immobilization and detoxification of Cr(VI)[94]. Simultaneously, the carbon matrix provides structural stability, retards iron leaching, and facilitates electron shuttling via π-conjugated systems and redox-active quinone groups[95,96].

Beyond chromium remediation, Fe–C interactions enhance the sorption capacity of modified biochar for phosphate and heavy metals. Iron hydroxides and oxides furnish abundant binding sites for anionic species, while the biochar matrix maintains high dispersion and mechanical stability[97,98]. The incorporation of zero-valent iron (ZVI) further strengthens reductive immobilization processes, enabling detoxification of contaminants such as Cr(VI) and U(VI), thereby improving the environmental safety of contaminated systems[99]. More broadly, Fe–BC removes pollutants through a synergistic integration of adsorption, catalytic oxidation, reduction, and electron transfer. The introduction of iron species increases surface area, porosity, and the abundance of functional groups, thereby enhancing adsorption efficiency and ensuring close contact between pollutants and reactive sites. Crucially, Fe–BC also serves as an effective catalyst in advanced oxidation processes (AOPs), where Fe2+/Fe3+ cycling and embedded iron oxides or ZVI activate oxidants such as H2O2, peroxymonosulfate (PMS), and peroxydisulfate (PDS), generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) including •OH, SO4•−, O2•−, 1O2, and high-valent Fe(IV)/Fe(V) species. These intermediates drive the oxidative degradation of a wide range of organic pollutants, often operating in parallel with direct reduction pathways such as the conversion of Cr(VI) to Cr(III). Furthermore, the graphitic domains and structural defects within the carbon matrix facilitate electron transfer, sustain redox cycling, and prolong catalytic activity. By coupling pre-adsorption with catalytic degradation, Fe–BC not only concentrates contaminants at its surface but also decomposes them into less harmful products, thereby achieving more efficient and sustainable remediation compared with unmodified biochar[100].

Research priorities

-

Despite significant advances, several critical research areas remain to be addressed to harness the potential of Fe-modified biochar systems fully: (1) Redox stability and aging behavior—Long-term field performance of iron-modified biochar under varying pH, redox, and microbial conditions remains poorly understood. Studies must assess how Fe–C interactions evolve and influence the retention and release of contaminants; (2) Structural characterization at the nanoscale—Advanced tools such as X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS), Mössbauer spectroscopy, and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) are essential for elucidating the oxidation states, bonding environments, and spatial distribution of Fe species within the biochar matrix[101]; (3) Controlled synthesis for target—specific applications. Future research should develop standardized, scalable, and cost-effective iron-loading methods optimized for specific pollutants (e.g., nitrate, arsenic, PFAS). The nature of the biomass precursor and the type of iron salt must be tailored to achieve the desirable surface chemistry; (4) Environmental trade-offs and life-cycle analysis. Studies must evaluate the potential risks associated with Fe leaching, nanoparticle toxicity, and greenhouse gas emissions. A systems-level life-cycle assessment of Fe-modified biochar will guide its sustainable implementation[102]; (5) Integration in treatment systems—There is growing interest in deploying Fe-modified biochar in constructed wetlands, bioreactors, and permeable reactive barriers. Field-scale studies assessing regeneration potential, hydraulic behavior, and pollutant removal kinetics are urgently needed[100]. Thus, iron-modified biochar represents a promising multifunctional material at the interface of carbon and iron chemistry. A deeper mechanistic understanding of Fe–C interactions and the development of targeted modification strategies will significantly advance its application in pollution control, nutrient cycling, and climate-smart agriculture.

-

Some research confirms that modified biochar costs almost half that of activated carbon (Table 3). However, its adsorption capacity is comparable to that of activated carbon[103]. At the same time, the adsorption capacity of modified biochar for contaminants is much higher than that of other inexpensive adsorbents. Currently, the feedstock used in biochar production is primarily solid waste from agricultural, forestry, or sewage sludge sources, enabling the resource-oriented utilization of solid waste. Furthermore, the by-products generated during the preparation and modification of biochar can be utilized for energy recovery, further contributing to cost reduction[104].

Most types of modified biochar, including acid- and alkali-modified biochar and magnetic-modified biochar, exhibit excellent regeneration capabilities. Typically, modified biochar can maintain a stable and high adsorption capacity over three to five cycles[45,105,106]. Although the production of modified biochar, which involves the use of various modifying reagents or techniques, is more expensive than that of pristine biochar, its application cost in actual remediation processes is lower. This is attributed to the higher adsorption capacity of modified biochar and its greater potential for reuse.

Table 3. Cost-benefit comparative analysis table of modified biochars for pollutant removal

Modified biochar Target pollutant Modification method Key cost advantage Cost efficiency

(USD/g pollutant)Ref. Na2S-BC Hg(II) One-step pyrolysis with Na2S Use of industrial byproduct Na2S; Simplified one-step process. 1.74 [107] K2FeO4-BC Heavy metals Pyrolysis + K2FeO4 impregnation High regeneration capability; Biomass oil/gas byproducts offset energy cost. Becomes cheaper

after three cycles[108] Fe-BC P Chemisorption with Fe3+ Feedstock is waste with gate fee; modifiers from scrap metal/waste. ~2.00 [109] Ca-BC P Chemisorption with Ca2+ Feedstock is waste with gate fee; modifiers from scrap metal/waste. ~1.50 [109] Struvite precipitation P Chemical precipitation Benchmark for P recovery ~17.29 [109] Ca/Mg-BC P One-step co-modification with CaCl2/MgCl2 Very low-cost waste feedstock; high capacity. 0.66 [110] Amine-modified BC Dimethyl sulfide HNO3/NH3 ammoxidation Free feedstock; modification cost is low. 2.28 [111] Commercial AC Dimethyl sulfide — Benchmark for comparison 2.62 [111] -

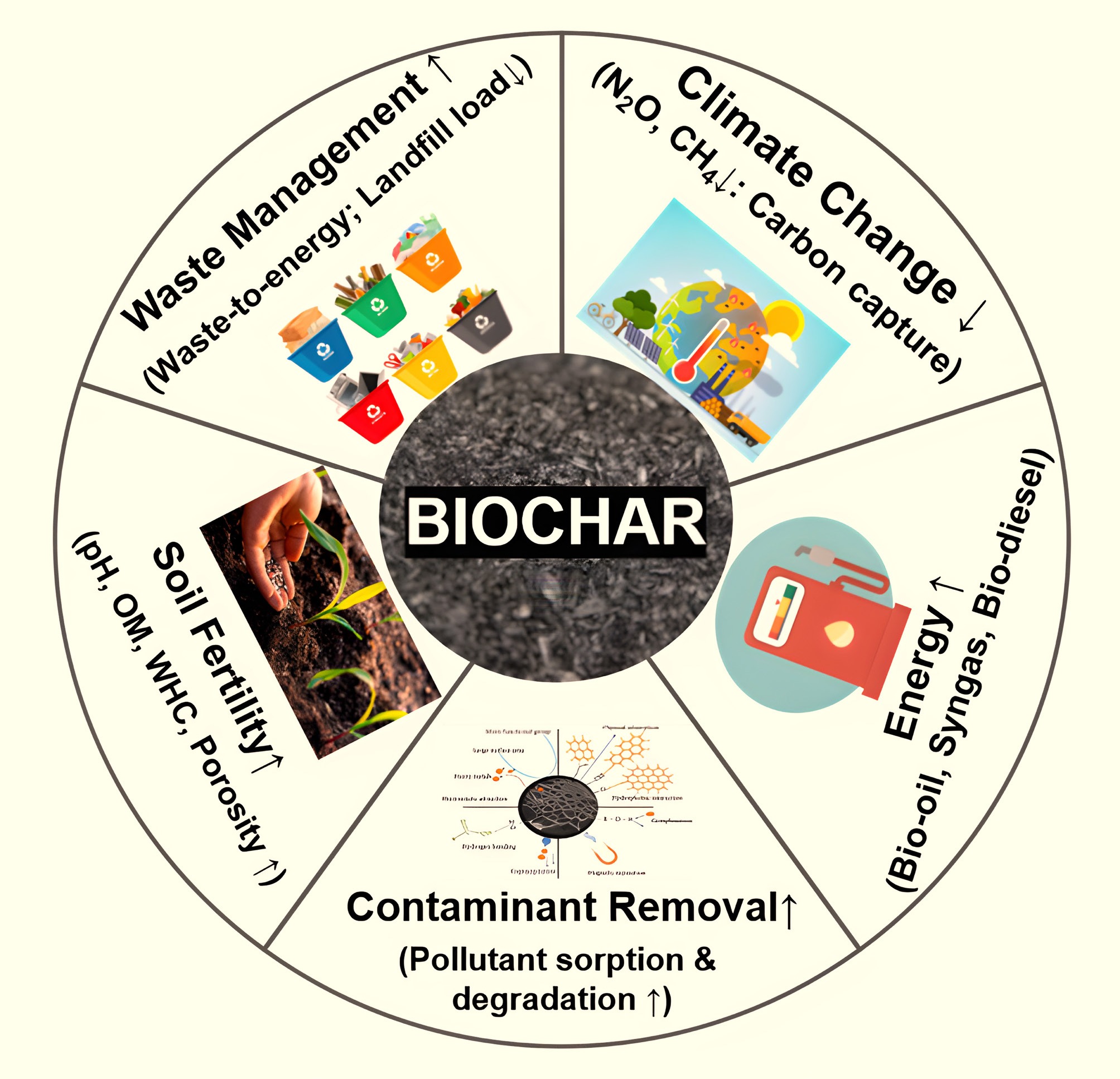

Modified biochar has exhibited excellent remediation capabilities for air, soil, and water pollution (Fig. 4). For instance, previous literature has shown that the adsorption capacity of modified biochar for SO2 surpasses that of unmodified biochar[112,113]. Additionally, modified biochar can influence soil microorganisms, reducing the denitrification pathway that converts nitrous oxide to nitrogen. This significantly lowers N2O emissions[114].

Modified biochar effectively remediates various types of soil, particularly saline or heavy metal-contaminated agricultural and forest soils[115,116]. The primary application methods for modified biochar in soil include topsoil incorporation, deep application, and follow-up fertilization. The remediation process mainly occurs through adsorption[117]. Furthermore, using modified biochar can enhance soil fertility and increase crop yields[118]. It can also be utilized to boost microbial activity and regulate plant abundance[117,119]. One of the primary applications of biochar is its role in enhancing the soil's physical and chemical properties. Numerous studies have reported that the incorporation of biochar into agricultural soils offers several benefits, including improved soil water availability, increased water-holding capacity, enhanced soil organic carbon content, and the stimulation of microbial activity[120]. Additionally, biochar amendments are widely utilized to mitigate the leaching of soil contaminants. The application of wheat straw biochar to soil resulted in the transport of 35% of the applied herbicide, 4-chloro-2-methylphenoxyacetic acid (MCPA), compared to 56% transport in non-amended soil[121]. In another study, Yavari et al.[122] reported that only 2.8% of the herbicide imazapyr was leached in soil amended with oil palm empty fruit bunch biochar, compared to 14.2% leaching in unamended soil. In contrast, soil containing oil palm empty fruit bunch biochar alone exhibited 4% leaching. Manna and Singh[123] reported that 78% of the herbicide pyrazosulfuron-ethyl (PYRAZO) leached from untreated sandy loam soil. However, when the soil was amended with rice straw biochar pyrolyzed at 400 °C, PYRAZO leaching was reduced by 25%–58%. In soil treated with rice straw biochar pyrolyzed at 600 °C, the reduction in leaching ranged from 55%–67%. These findings suggest that biochar can serve as an effective medium for mitigating the leaching of contaminants from soil into surface and groundwater systems.

Modified biochar has been demonstrated to be effective in adsorbing various pollutants in aquatic environments, including organic pollutants, inorganic pollutants, and emerging contaminants such as microplastics. Its adsorption efficiency is significantly higher than that of pristine biochar. Currently, the most effective method for removing heavy metal contaminants from aqueous solutions is adsorption using biochar. Biochar produced through various modification methods contains different functional groups, resulting in varying adsorption capacities for specific heavy metals[124]. Furthermore, recent studies indicate that modified biochar serves as a cost-effective and reusable adsorbent for the removal of antibiotics[125], dyes[56], PFAS[46], and microplastic contaminants[49].

Several large-scale field trials have confirmed the feasibility of applying modified biochar. A field study on pumpkin cultivation in Nepal demonstrated that the addition of a cow urine-biochar combination (0.75 tons/ha of biochar and 6.3 m3/ha of cow urine) increased yields by 300% compared to urine-only treatments and by 85% compared to biochar-only treatments[126]. A 4-year field trial on corn and soybean yields in the District of Columbia showed no increase in corn yields during the first year. However, yields increased by 20%, 30%, and 140% in the second, third, and fourth years, respectively[127]. This suggests that biochar requires a certain degree of aging in the soil before it has a positive impact on crop yields. As biochar ages in the composting medium, it gradually forms an organic coating on its surface, which enhances nutrient retention compared to fresh biochar[128].

Iron-modified biochar applications

-

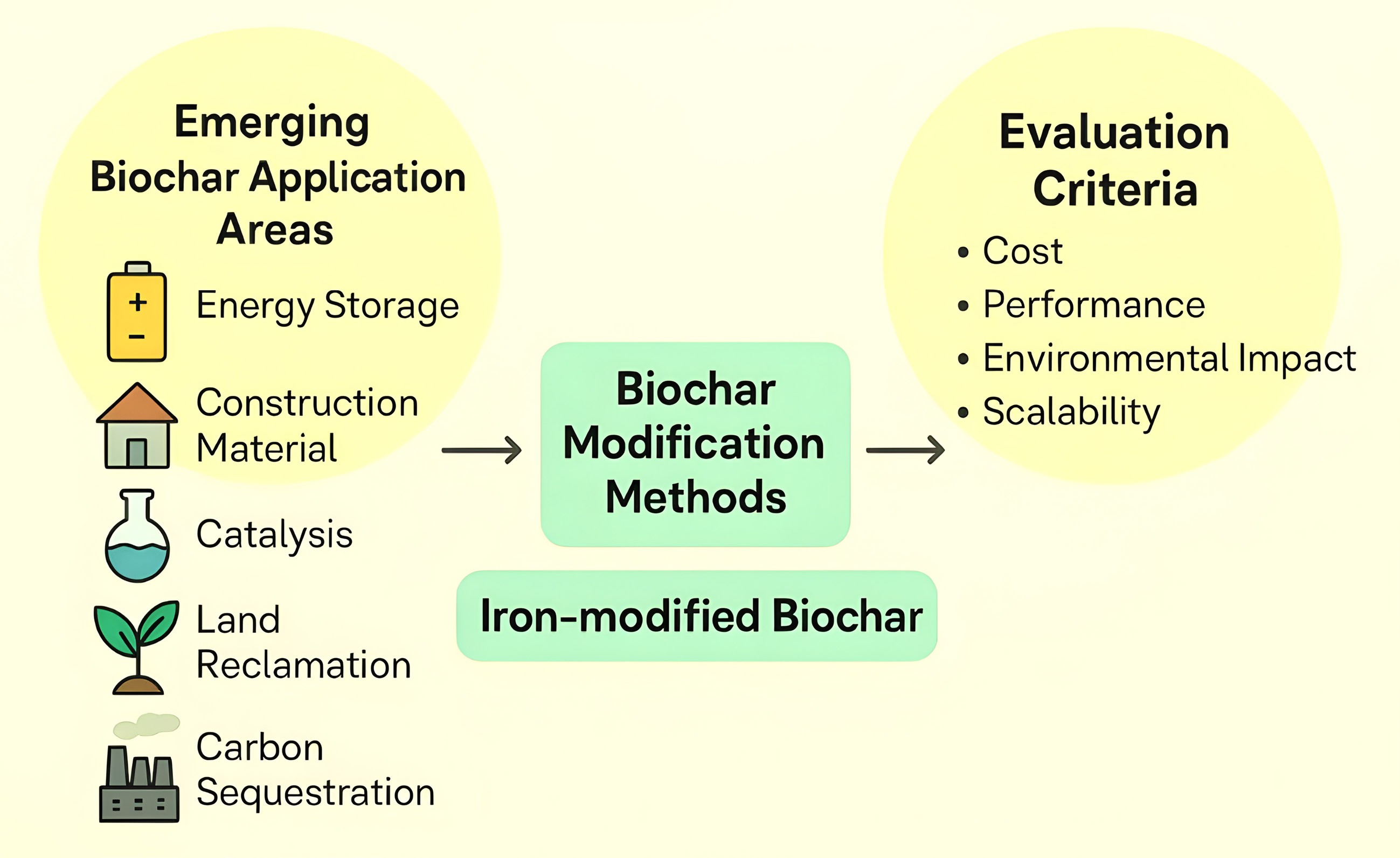

Biochar has garnered global attention for its multifaceted roles in environmental sustainability, including carbon sequestration, enhancing soil fertility, pollution remediation, and energy applications. Recent years have witnessed an expansion of biochar utilization beyond traditional soil amendments to advanced fields, including wastewater treatment, composite materials, energy storage, and climate change mitigation. These emerging application areas, while promising, have introduced a critical need for robust evaluation frameworks to assess performance, stability, and environmental impact. However, a significant gap persists in the depth and consistency of research related to biochar modification methods, particularly the use of iron-modified biochar (Fe-biochar) in these evolving domains (Fig. 5).

The rapid diversification of biochar applications has introduced new opportunities and complexities. In wastewater treatment, biochar is increasingly employed for removing heavy metals, nutrients, dyes, and organic pollutants due to its porosity and surface chemistry[20]. Iron-functionalized biochar has demonstrated an enhanced affinity for anions, such as phosphate and arsenate, as well as for redox-active pollutants like Cr(VI) and nitroaromatic compounds[129]. In catalysis and advanced oxidation processes (AOPs), Fe-modified biochar acts as a catalyst in Fenton-like reactions, generating reactive oxygen species to degrade persistent organic pollutants[130]. In energy applications, iron-modified biochar is also being explored for use in supercapacitors, batteries, and as a support material for electrocatalysts, owing to its conductivity and redox potential[131]. Despite these advances, the underlying structure-function relationships, especially those involving Fe–C interactions, are often insufficiently studied or reported. Studies tend to focus on performance metrics (e.g., adsorption capacity or degradation rate) without deeply characterizing the physicochemical transformations and reaction mechanisms of iron within the biochar matrix under environmental or operational conditions.

Evaluation criteria: toward standardization

-

A recurring concern in the literature is the insufficient mechanistic understanding of how iron species are distributed, interact with the carbon matrix, and behave under operational conditions. For example, while numerous papers report enhanced phosphate or arsenic removal by Fe-modified biochar, only a subset investigates whether adsorption occurs via ligand exchange, electrostatic attraction, or surface precipitation, and even fewer distinguish between contributions from Fe(II), Fe(III), and ZVI (zero-valent iron) phases[97]. Similarly, while pyrolysis temperature and biomass feedstock type are known to affect the dispersion of iron nanoparticles and the porosity of biochar, comprehensive investigations of these parameters are scarce. Most existing work does not systematically explore how modification variables (e.g., iron precursor type, loading concentration, activation method) impact surface chemistry and reactivity across different functional applications. Moreover, scaling up the synthesis of Fe-modified biochar remains a challenge due to concerns over cost, consistency, and environmental safety. Research typically remains confined to lab-scale studies with limited field validation or techno-economic analysis. Without detailed pilot studies, policy and commercial adoption will remain restricted.

The lack of standardized, universally accepted evaluation criteria for modified biochar further impedes scientific progress. Researchers often employ diverse units, batch adsorption protocols, and characterization techniques, which make comparative analysis challenging. There is an urgent need for harmonized criteria based on the following aspects: (1) Structural and chemical characterization—including detailed analysis of pore distribution, iron oxidation states, and surface functional groups using XPS, BET, FTIR, and Mössbauer spectroscopy[101]; (2) Environmental stability and leaching behavior—evaluating Fe leachability and structural integrity under field-relevant pH, redox, and microbial conditions to predict long-term performance; (3) Reusability and regeneration—systematically assessing the ability of Fe-biochar to maintain its sorption or catalytic capacity over multiple cycles, particularly in water treatment applications; (4) Life cycle assessment (LCA)—expanding cradle-to-grave evaluations of Fe-modified biochar to including energy input during synthesis, environmental benefits, and potential ecotoxicity[41]. In the absence of these standardized protocols, many research efforts remain case-specific and exploratory rather than contributing to cumulative knowledge or practical scalability.

-

Biochar modification, particularly with iron, has shown significant potential in enhancing the physicochemical properties of raw biochar, enabling its application in soil remediation, wastewater treatment, and energy storage. Despite the growing body of literature on this topic, several knowledge gaps and future research avenues remain unexplored or inadequately addressed. This section outlines critical future research directions necessary to optimize biochar modification strategies and expand the practical applications of iron-modified biochar (Fe-modified biochar).

Standardization of modification protocols

-

One of the primary challenges in biochar research is the lack of standardized methods for modifying biochar, particularly when incorporating metal ions such as iron. The properties of Fe-modified biochar vary significantly depending on the biomass feedstock, pyrolysis conditions, iron precursor used, and the modification technique (e.g., co-pyrolysis, post-pyrolysis impregnation, or precipitation methods). Comparative studies using consistent protocols and controlled variables are needed to determine the most efficient and reproducible methods for modifying biochar with iron across diverse feedstocks. Establishing universal guidelines for Fe-modified biochar synthesis will facilitate comparative assessments and scalability across various industrial and environmental applications[29,132].

Mechanistic understanding of pollutant interactions

-

Although many studies demonstrate improved adsorption capacities of Fe-modified biochar for heavy metals (e.g., Pb, Cd, As) and anions (e.g., phosphate, nitrate), the precise mechanisms of interaction—particularly at the molecular level—are not fully understood. Advanced analytical techniques such as X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES), Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), and synchrotron-based imaging should be employed more systematically to explore the binding pathways, redox transformations, and surface complexation processes of contaminants with Fe-modified biochar[133]. Moreover, computational modeling and density functional theory (DFT) simulations can complement experimental data to elucidate the energetics and kinetics of sorption mechanisms.

Lifecycle and environmental risk assessments

-

A critical limitation in current Fe-modified biochar research is the lack of comprehensive life-cycle assessments (LCAs) and environmental risk analyses. While Fe-modification enhances biochar's functional performance, it may introduce potential risks, including iron leaching, ecotoxicity, and disruption of soil microbial ecology over the long term. Future research should include detailed studies evaluating the fate and transport of iron species in Fe-modified biochar-amended soils and aquatic systems. Additionally, LCAs comparing the environmental footprint of modified versus unmodified biochar (from synthesis to end-of-life) will help determine these materials' sustainability and commercial viability[16,45].

Multifunctional and hybrid biochar composites

-

Emerging research suggests that combining iron with other functional materials such as graphene, nanosilica, zeolites, or layered double hydroxides can lead to the development of multifunctional Fe-modified biochar composites with enhanced sorption, catalytic, and redox capabilities[43]. These hybrid systems show promise for the remediation of complex contaminants, such as the simultaneous removal of heavy metals and antibiotics, as well as emerging contaminants. However, more interdisciplinary work is needed to optimize the composition, structure, and stability of such composites under real-world environmental conditions. Further investigation into their reusability, regeneration methods, and scalability is also essential.

Field-scale validation and pilot studies

-

Most studies on Fe-modified biochar have been confined to laboratory-scale batch experiments, limiting their applicability in real-world settings. Future research should focus on field-scale pilot trials across varied agroecosystems, polluted water bodies, and industrial effluent treatment plants to validate the performance of modified biochar under diverse environmental stresses. These studies should assess long-term performance metrics, including degradation rates, improvements in soil fertility, contaminant immobilization, and carbon sequestration efficiency[24]. Collaborations with local industries, farmers, and environmental agencies will facilitate the integration of Fe-modified biochar into broader ecological management frameworks.

Integration with circular bioeconomy models

-

To fully realize the potential of biochar technologies, especially Fe-modified biochar, research must also focus on their role within a circular bioeconomy framework. Future work should investigate how waste biomass and industrial byproducts (e.g., iron-rich sludges, mining waste, red mud) can serve as sustainable sources for Fe-modified biochar production, thereby closing resource loops and reducing environmental burdens. Moreover, economic analyses and techno-economic assessments (TEAs) must be conducted to evaluate the profitability of Fe-modified biochar applications at industrial scales[48,125]. Integrating bioenergy production (e.g., syngas, bio-oil) through co-pyrolysis can also improve system efficiency and cost-effectiveness.

Application in climate resilience and soil carbon sequestration

-

There is growing interest in using biochar for climate resilience, particularly through soil carbon sequestration and drought mitigation. While standard biochar has shown promise in this area, Fe-modified biochar may offer additional benefits due to its role in redox cycling, which improves soil structure and enhances nutrient retention. Future studies should investigate the comparative efficacy of Fe-modified biochar in enhancing carbon storage and mitigating greenhouse gas emissions (especially N2O and CH4) under different land use conditions. Long-term agronomic trials will be crucial in determining its impact on crop yield, shifts in microbial communities, and ecosystem health[134].

Smart biochar and sensor applications

-

A novel but underexplored direction is the development of 'smart biochar' systems incorporating iron-based nanomaterials for environmental sensing and controlled release applications. Fe-modified biochar can be engineered to function as a redox-responsive material capable of sensing changes in pH, heavy metal concentration, or redox potential in soils and water. Integrating biosensors or optical markers into biochar frameworks could lead to real-time monitoring tools for environmental remediation systems, offering a dual role as both remediation agent and analytical platform[44].

-

Iron-functionalized biochar represents a compelling intersection of materials science, environmental engineering, and sustainable agriculture. While current research has laid a robust foundation, advancing the field requires a more integrated, interdisciplinary approach. Future studies should focus on uncovering mechanistic insights, implementing long-term field trials, conducting comprehensive risk assessments, and aligning applications with the principles of the circular economy. These steps are crucial for bridging the gap between experimental findings and large-scale, real-world implementation. This review has examined current biochar modification strategies, highlighted their practical advantages, and evaluated their readiness for field applications. Through chemical and physical tailoring, biochar can be engineered to exhibit high surface activity, enhancing its capabilities in pollutant removal. Notably, modified biochar has gained attention as an effective adsorbent, catalyst, and catalyst support for environmental remediation. Its ability to transform organic and inorganic waste into functional materials underscores its value as a sustainable, cost-effective solution for pollution control. Among various modifications, iron-functionalized biochar shows exceptional promise for multifunctional environmental applications, including water treatment, redox catalysis, and nutrient recovery. However, critical challenges remain. Research must move beyond general feasibility toward standardized methodologies, consistent evaluation criteria, and deeper investigation into iron-carbon interactions. Addressing these gaps is crucial to realizing the full potential of iron-modified biochar in emerging domains. To catalyze progress, future research should emphasize advanced material characterization, environmental impact analysis, and scalability assessments. Strong interdisciplinary collaboration among chemists, engineers, environmental scientists, and policymakers will be crucial to developing reliable, eco-friendly, and commercially viable biochar technologies that can effectively address complex environmental challenges.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: methodology, formal analysis, investigation, and writing: Zhang Y; review and editing: Chen H; resources, conceptualization, visualization, writing, review and editing, supervision, project PI: Islam S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

This work is supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, United States Department of Agriculture (USDA-NIFA) (Grant No. GR 019129 entitled 'Iron Biochar for Agri-pollution control').

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Comprehensive review of biochar modification methods, with an emphasis on iron-modified biochar (Fe–biochar).

Clarifies Fe–C interactions driving adsorption, redox activity, and electron transfer mechanisms.

Explores emerging Fe–biochar applications in remediation, energy storage, and smart sensing.

Proposes future directions linking Fe–biochar with circular bioeconomy and climate-resilient agriculture.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang Y, Chen H, Islam S. 2025. Advances in biochar modification for environmental remediation with emphasis on iron functionalization. Biochar X 1: e009 doi: 10.48130/bchax-0025-0010

Advances in biochar modification for environmental remediation with emphasis on iron functionalization

- Received: 22 July 2025

- Revised: 23 September 2025

- Accepted: 17 October 2025

- Published online: 05 November 2025

Abstract: Biochar, a porous carbonaceous material produced from biomass pyrolysis under limited oxygen, has emerged as a promising material for environmental remediation due to its stability, adsorption capacity, and potential for carbon sequestration. Though raw or unmodified biochar often exhibits limited surface functionality, low surface area, and poor affinity for specific contaminants, its effectiveness in practical applications is restricted. Various modification techniques have been developed to address these limitations, including physical activation, chemical functionalization, and surface doping with metals. Among these, iron-modified biochar (Fe-BC) has attracted considerable attention due to the unique redox properties of iron and its strong binding affinity for anions and organic pollutants. Fe-BC is typically synthesized through impregnation, co-pyrolysis with iron salts, or post-pyrolysis treatment. These modifications enhance the surface area and porosity and introduce reactive sites that significantly improve the sorption of phosphate, arsenic, heavy metals, and dyes from wastewater, as well as facilitate catalytic reactions such as Fenton-like oxidation. Recent studies have demonstrated the multifunctionality of Fe-BC in wastewater treatment and soil remediation, as well as in agriculture as a slow-release nutrient carrier. Moreover, novel synthesis approaches using green chemistry principles and low-cost iron precursors have made Fe-BC more sustainable and scalable. Despite its potential, challenges remain regarding the long-term stability of leaching iron, regeneration, and environmental risks. This review provides a comprehensive analysis of current modification strategies for biochar with a focused evaluation of Fe-BC, including synthesis methods, physicochemical properties, contaminant removal mechanisms, and practical applications. Future perspectives are discussed to guide research toward optimizing Fe-BC for the circular economy and sustainable environmental technologies.