-

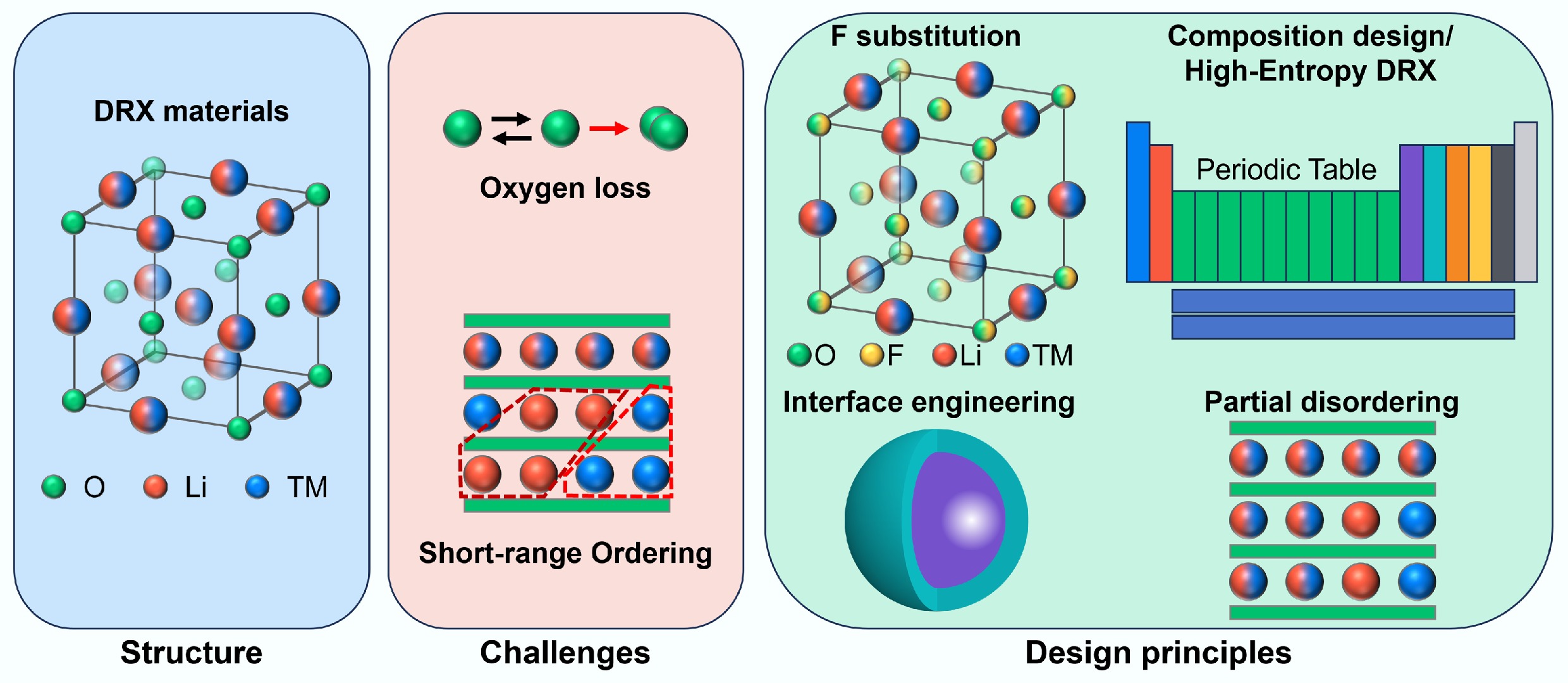

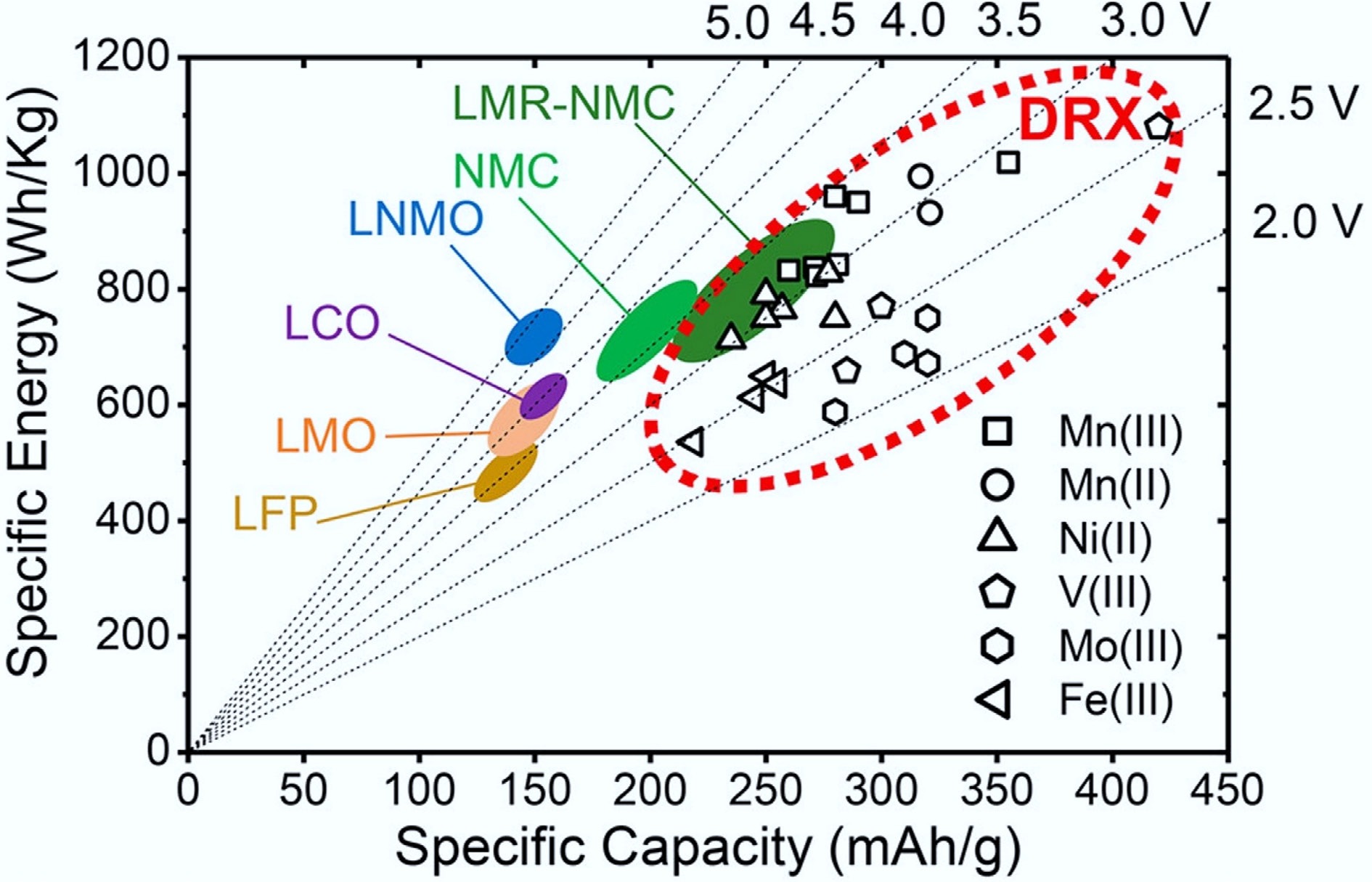

Global energy transitions toward renewable sources and electric vehicles (EVs) demand lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) with higher energy density, enhanced safety, and sustainable material profiles. While commercial layered oxides (e.g., LiCoO2, NMCs) dominate current markets, their capacity limitations (< 250 mAh g−1), and reliance on scarce elements like cobalt constrain further advancements[1−5]. Cation-disordered rock-salt (DRX) cathodes have recently gained attention as a promising class of materials to replace conventional layered oxide cathodes due to their potential for high capacity (> 300 mAh g−1), high energy density (300–1,000 Wh kg−1) (Fig. 1a)[6], excellent rate performance (even at fast charging/discharging rates of 5C or higher), diverse transition-metal chemistries tolerance, and high theoretical structural stability[7].

Figure 1.

Comparison of DRX and other cathode materials in specific capacity and energy. Reproduced with permission, Copyright © 2021, American Chemical Society[6].

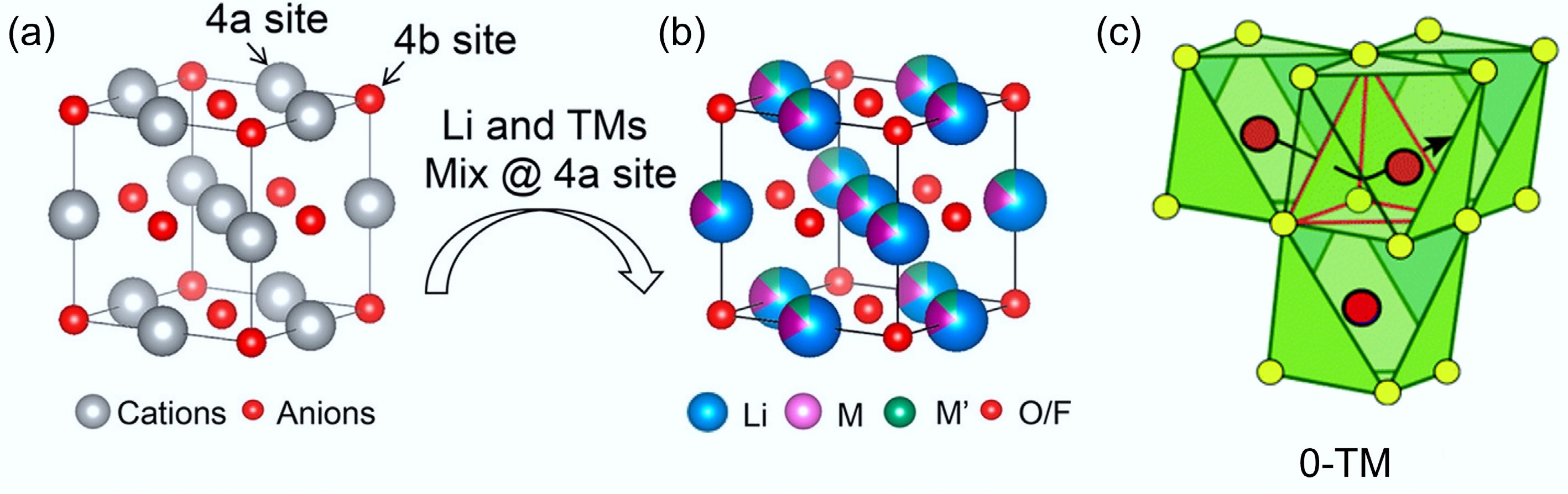

DRXs gain their name because Li and transition-metal cations randomly occupy the 4a octahedral sites of the interpenetrating face-centered cubic lattice, and thus they do not exhibit long-range atomic ordering. Owning to this structure, DRXs prossess distinctive Li-ion transport pathways via three-dimensional octahedral-tetrahedral-octahedral (o-t-o) networks, which are also known as '0-TM' channels. Such Li-ion hopping can avoid face-sharing between Li and transition metals (TMs) in the octahedra, hence reducing migration barriers and supporting higher rate capability[8,9]. As this structure can accommodate a diverse range of transition metals, and is thermodynamically stable without experiencing large Li-diffusion channel volume change, DRXs can exhibit excellent structural resilience[10,11]. In addition, DRXs usually contain a large amount of Li-O-Li linkages and promote anionic redox, hence supporting significantly higher capacity than that of traditional cathode materials[12−14].

Challenges such as oxygen loss and short-range ordering (SRO) significantly influence the electrochemical performance and long-term stability of DRXs, and hinder the translation of their theoretical advantages into practical applications. Firstly, the same Li-excess and Li-O-Li environments that activate high-capacity oxygen redox also predispose DRXs to irreversible oxygen loss at high voltage, triggering surface densification, impedance growth, voltage hysteresis, and rapid capacity fade[1,15−18]. Secondly, SRO that persists in the local structure can fragment the 0-TM percolation network, limiting the Li-ion mobility[19−23].

To gain insight into these challenges, this review integrates mechanistic understanding with actionable design strategies. After outlining structural fundamentals and composition of DRXs, oxygen-redox behaviour and O-loss pathways are dissected, and then how SRO originates and how it disrupts Li percolation is examined. Building on these foundations, strategies that have proven effective for high-performance DRX design, including composition adjustment, fluorine substitution, interface engineering, and construction of a partially disordered structure are critically evaluated. Finally, the potential ways to address these challenges and improve the performance of DRX materials are also proposed. Specifically: (1) a suitable Li-excess extent is recommended (just above the percolation threshold to allow efficient Li transport, but not too high to induce irreversible oxygen redox); (2) deploy moderate, composition-specific fluorination to stabilize oxygen without blocking Li percolation; (3) engineer interfaces to suppress irreversible oxygen loss; (4) suppress SRO via introducing high-entropy cation mixture; and (5) constructing nucleate size-limited partially disordered domains to introduce low-barrier diffusion channels without sacrificing global disorder. It is hoped this review can provide guidance from mechanistic understanding to the design of manufacturable DRX cathodes towards high-energy lithium-ion batteries.

-

DRXs are developed from the conventional ordered rocksalt framework with the

$\rm Fm{\overline 3}m $ $\rm R{\overline 3}m $ $\rm Fd{\overline 3}m $ Although DRXs have no long-range cation order, they still support Li transport via octahedral–tetrahedral–octahedral hops that traverse '0-TM' tetrahedral sites (those that do not face-share with any TM octahedra) with a low energy barrier[24]. When Li is in excess, these 0-TM hops statistically connect into a three-dimensional percolating network that enables high practical capacities (Fig. 2c)[11]. As such Li+ migration pathways do not involve direct face-sharing with transition metal cations; they can significantly reduce the repulsive electrostatic interactions and minimise migration energy barriers, thus leading to enhanced Li-ion mobility, long-range diffusion, and improved electrochemical performance. More importantly, due to the three-dimensional Li diffusion pathway and random cation distribution in DRXs, the interlayer-spacing-change-induced interlayer collapse during deep delithiation can be prevented. Therefore, DRXs theoretically have superior structural stability compared with layered oxides, especially under high-voltage cycling[26,27].

Despite the fact that DRXs have a random occupation of cation sites without long-range cation ordering, problematic short-range ordering (SRO) can still exist within this framework[20]. In fact, the formation and stability of the disordered structure depend significantly on the presence of redox-inactive d0 transition metals and Li/TM ratio, which minimise the crystal field stabilisation energy and allow greater flexibility in local coordination environments. The impact of these factors will be discussed in detail in the following sections.

Critical composition of DRXs

The role of d0 transition metal elements

-

DRXs are typically formulated as Li1+x(MM')1−xO2, where M represents redox-active transition metals and M′ denotes redox-inactive d0 transition metals. The d0 TMs are transition metals without valence d electrons (such as Ti4+, Nb5+, and Mo6+); they are key components in stabilising the DRX phase due to their distinct electronic and structural behaviour. The ability of a rock-salt structure to accommodate cation disorder depends heavily on the electronic configuration of the TMs. Urban et al.[28] proposed that the occupancy of d-orbitals significantly affects the energetic cost of octahedral distortions in the face-centred cubic rocksalt lattice. Since DRXs consist of edge-sharing MO6 octahedra, local distortions from ionic size or charge mismatch must be compensated by neighbouring sites. Therefore, the total energy of the structure depends on how easily different cations can tolerate or accommodate these distortions.

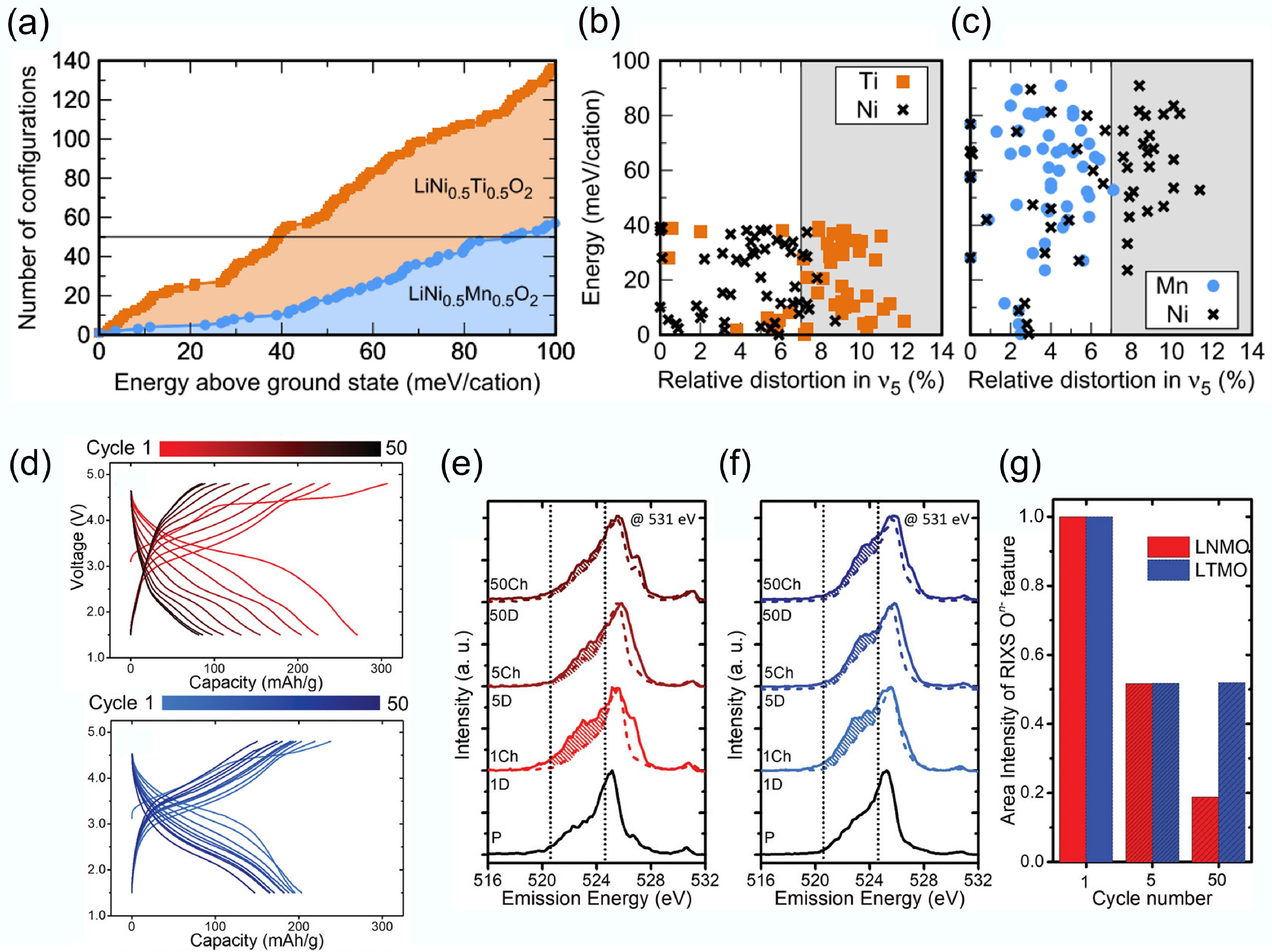

Since Li+ ions lack d-orbital electrons and crystal field stabilisation energy, they do not exhibit a particular preference for octahedral shapes. Consequently, the disorder in LiMO2 can be predicted solely based on the filling of d orbitals in the TMs. Each filled orbital imposes a specific preferred mode of octahedral distortion. Utilising DFT, Urban et al.[28] calculated the distribution of distortion energies for different LiMO2 compositions. They found LiNi0.5Ti0.5O2 has a significantly higher number of configurations within a specific energy range compared to LiNi0.5Mn0.5O2 (Fig. 3a). This indicates that, under the same synthesis conditions, more atomic orderings are thermally accessible for the Ti-containing composition. Figure 3b and c depict the displacement distortions of TM ions in the 50 most stable configurations for both materials. It can be observed that in LiNi0.5Ti0.5O2, the d0 Ti4+ cations can accommodate larger distortions in their sites while helping Ni2+ sites to maintain the preferred geometry.

Figure 3.

(a) Atomic configuration number of DRX materials. Energy per cation and TM site distortion of the stable (b) LiNi0.5Ti0.5O2 and (c) LiNi0.5Mn0.5O2 materials. Reproduced with permission, Copyright 2017, American Physical Society[28]. (d) Voltage profiles of LNMO and LTMO. (b)–(d) RIXS cut spectra of LNMO and LTMO. Reproduced with permission, Copyright © 2020 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim[29].

The structural benefits of d0 TMs arise from their low-lying, oxygen-dominated band structure and lack of crystal field stabilisation. On one hand, these cations can occupy highly distorted sites with minimal energy penalty. On the other hand, their flexibility to undergo distortion plays a vital role in minimising the distortions of other TM cations. As a result, d0 TMs are better suited for stabilising disordered rock salt phases, even when there are significant differences in ionic radii between the cation species. Therefore, the majority of reported DRX compositions incorporate at least one redox-inactive d0 TM to promote structural disorder and lattice stability, such as Ti4+, V5+, Nb5+, and Mo6+.

Although redox inactive d0 metals are inert in DRXs and do not directly relate to the cathode capacity, they play a critical role in tuning oxygen redox activity and capacity retention. Urban et al. suggested that the electronic configuration of d0 TM determines the formation and stability of the disordered rock-salt phase. In Fig. 3a–d, Chen et al. systematically compared Mn-based DRX cathodes with two different d0 elements: Li1.2Ti0.4Mn0.4O2 (LTMO) and Li1.3Nb0.3Mn0.4O2 (LNMO), ensuring the Mn content remained the same. Here, d0 TM cations Nb5+ and Ti4+ serve as 'redox modulator'[29]. Figure 3a illustrates an interesting comparison between cathode materials with the same Mn content but different d0 metals. When Nb5+ is utilised as the d0 metal, the cathode material exhibits a higher initial specific capacity, indicating a more pronounced O oxidation process. Conversely, when Ti4+ is employed as the d0 cations, the cathode material demonstrates improved cycling stability, which correlates with lower oxygen loss. According to RIXS analysis (Fig. 3b–d), Chen et al. compared the intensity retention of the oxidised oxygen features. They found the LTMO showed relatively reversible O redox activity upon charge and discharge cycling. Commonly, Nb5+ promotes overall O redox participation, while Ti4+ can stabilise the O redox process better. Therefore, even though the two d0 TMs are redox-inactive, they play distinct and complementary roles in DRXs' performance. This provides guidance to optimise the DRX's design via screening the suitable d0 TMs to balance the O redox and O loss.

Ratio of Li and d0 TMs

-

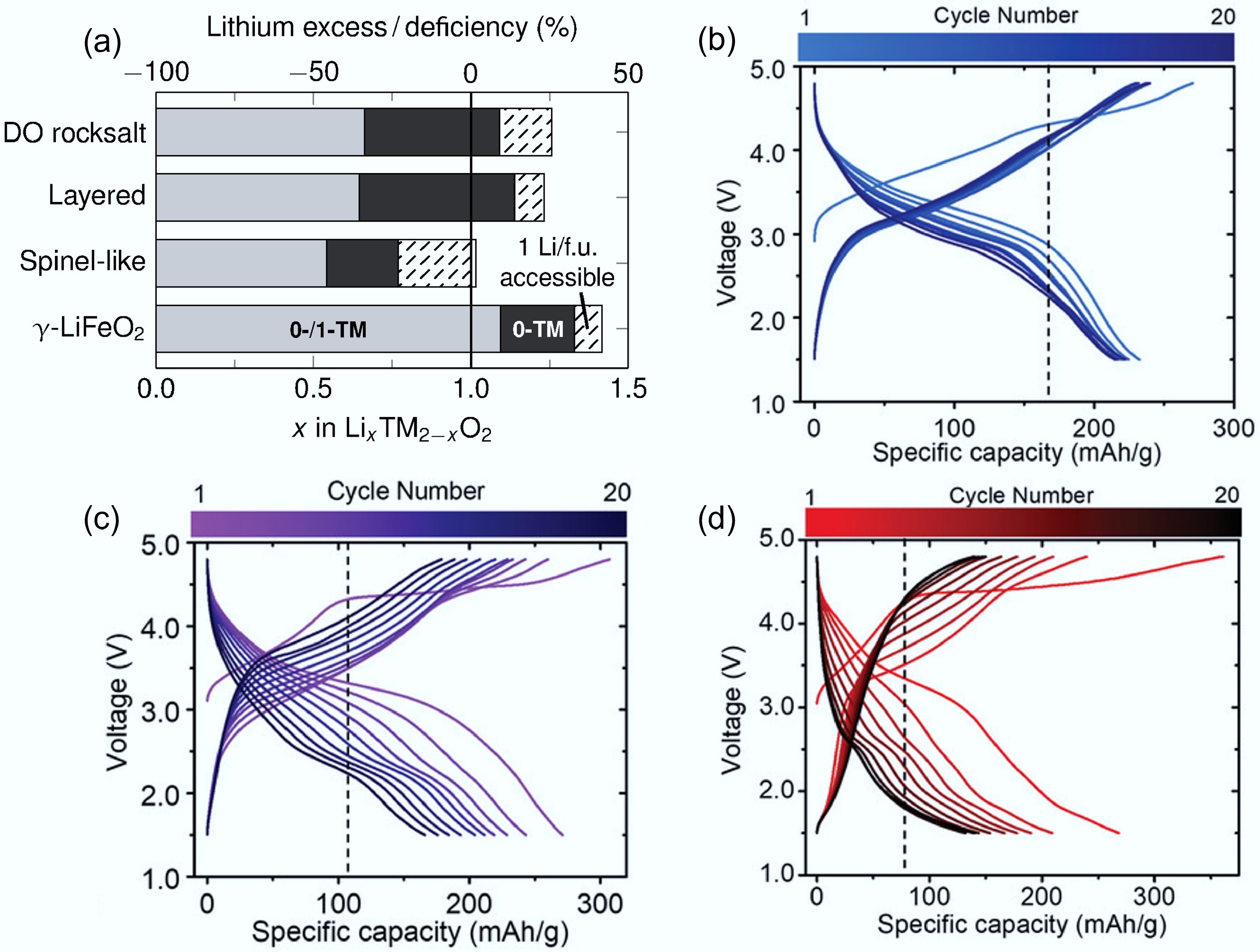

In addition to d0 TMs, the amount of Li excess and synthesis methods play significant roles in governing the cation-disordered rock-salt structure. As discussed above, 0-TM channels and Li percolation are the dominant features of DRXs, while a sufficient excess of Li is the key to forming a 0-TM tetrahedra percolating network. As shown in Fig. 4a[30], previous research demonstrated that a Li-excess of 10% (x > 1.1 in LixTM2−xO2) is a critical threshold to enable 3D-connected 0-TM pathways and bulk-percolative Li-ion transport, and is therefore required for high-performance DRXs[24,30,31]. Increasing Li content above this threshold increases the population and connectivity of 0-TM hops, but delivers diminishing returns as the network saturates[32]. For example, Urban et al. demonstrated that a rock-salt-type LiMO2 framework can support continuous Li diffusion through 0-TM channels even under full cation disorder when the Li/M ratio exceeds 1[33]. In addition to 0-TM channels, a suitable Li excess can also help maintain the disordered structure. The excess lithium ions can occupy interstitial sites or substitute for other cations, causing disruptions in the regular cation arrangement and promoting disorder.

At the same time, a higher ratio of Li/TM can increase the density of Li–O–Li linkages and promote anionic redox, which can boost capacity but exacerbate voltage hysteresis and instability if not carefully managed, underscoring a trade-off between transport and redox chemistry as Li content rises[22]. As Li and TMs mix with each other and share the same sites in DRX, higher Li content corresponds to lower TM content. While d0 TMs themselves do not contribute directly to capacity, a higher Li/TM ratio tends to favour oxygen redox by shifting the charge compensation away from the TM redox centres. This often results in a higher initial capacity but can also lead to increased structural instability and oxygen loss, ultimately reducing cycling life[6,34]. By comparing the performance of Nb-based DRXs with different Li/Mn ratios, Chen et al. found Li/Mn ratio of 1.3/0.4 in Li1.3Nb0.3Mn0.4O2 offered the best trade-off between capacity and cycling stability, indicating that optimising the Li/M ratio is essential for balancing energy density and durability in DRX cathodes (Fig. 4b−d)[34]. All these trends suggest that the Li-excess level should be balanced, in which the Li amount exceeds the percolation threshold, but not so high as to cause voltage hysteresis and instability.

Figure 4.

(a) Critical Li concentrations in different LIB materials. The grey (both 0-TM and 1-TM), and black (only 0-TM) regions represent the lithium content required for percolation. Reproduced with permission, Copyright © 2014 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim[30]. Charge/discharge curves of (b) Li1.2Nb0.2Mn0.6O2, (c) Li1.3Nb0.3Mn0.4O2, and (d) Li1.4Nb0.4Mn0.2O2. Reproduced with permission, Copyright © 2019 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim[34].

Structure-driven electrochemical properties of DRXs

-

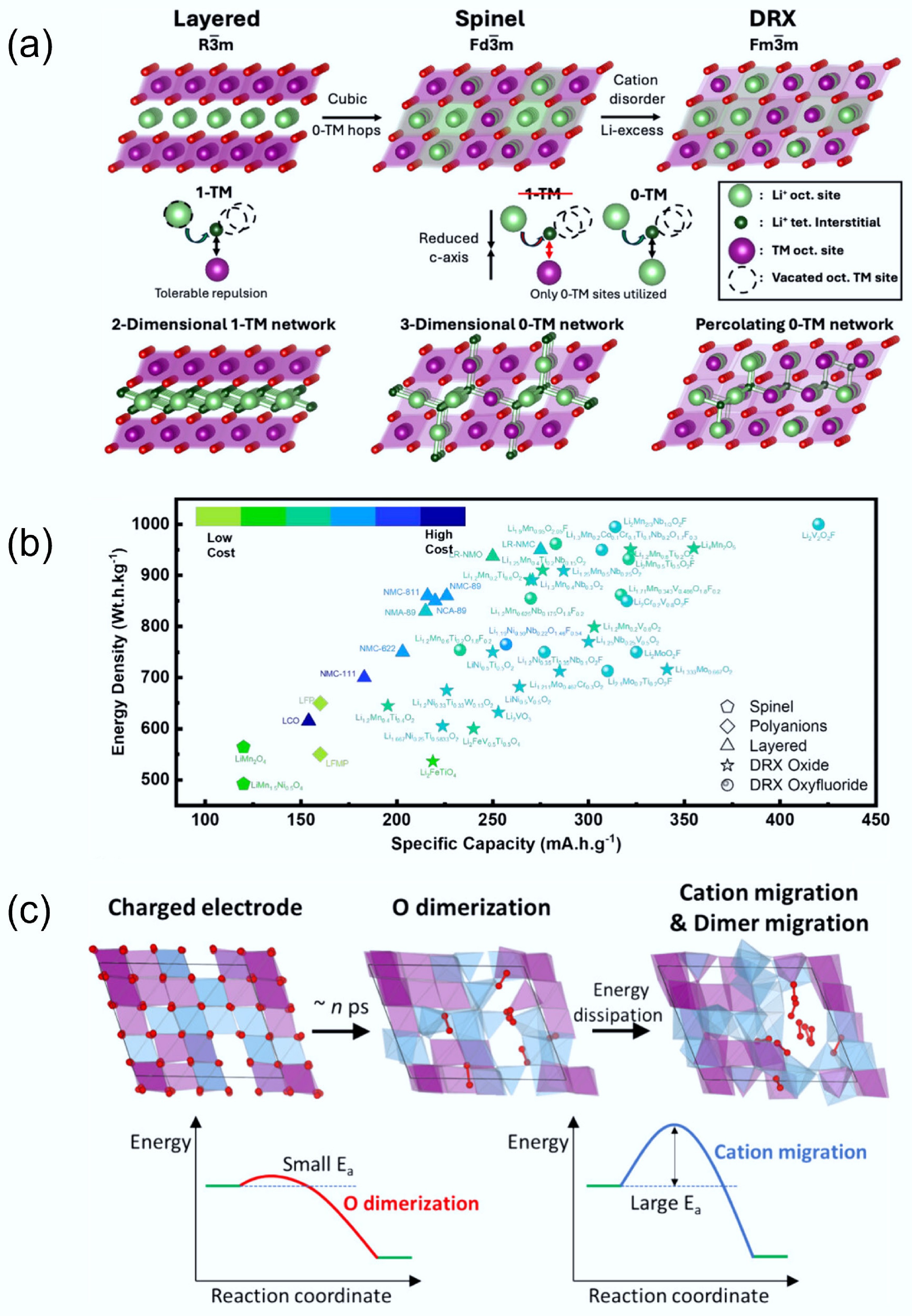

DRX cathodes exhibit electrochemical behaviour that is fundamentally governed by their unique structural characteristics. Figure 5a shows the different Li-transport behaviour of layered, spinel, and DRX materials. In layered cathodes (

$\rm R{\overline 3}m $ $\rm Fd{\overline 3}m $ $\rm Fm{\overline 3}m $

Figure 5.

(a) Li transport behaviour in different crystal structures. Reproduced with permission, Copyright © 2025 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim[9]. (b) Comparison of specific capacity and energy density between DRXs and traditional cathodes. Reproduced with permission, Copyright © 2024, American Chemical Society[8]. (c) Structure changes of DRX during the charging and discharging process. Reproduced with permission, Copyright © 2025, American Chemical Society[36].

As discussed previously, unlike conventional layered materials, the DRX lattice admits 0-TM channels in which Li+ migrates between octahedral sites through o-t-o that do not face-share with transition-metal (TM) octahedra[6]. The o-t-o migration barrier in 0-TM environments is substantially lower than that in 1-TM environments, enabling nearest-neighbour octahedral hops that accumulate into fast rate capability and long-range percolation when such environments are sufficiently connected[24]. This connectivity strongly depends on composition, as modest Li excess statistically raises the fraction and continuity of 0-TM tetrahedra, creating a 3D percolating network that supports macroscopic Li transport and underpins the high-capacity regime of DRXs[24,32]. Because these pathways are embedded in a robust rocksalt framework, DRXs can achieve specific capacities exceeding 300 mAh g–1 (Fig. 5b) without lattice collapse, surpassing layered counterparts while retaining broad compositional freedom[8,24].

However, the same structural disorder that enables high ionic conductivity in DRXs also leads to complex redox dynamics and structural rearrangements during cycling. Kim et al.[36] demonstrated in Li1.2Mn0.4Ti0.4O2 that deep delithiation at high voltage activates lattice oxygen redox, leading to the transient formation of peroxo-like O–O dimers. As illustrated in Fig. 5c, these dimers form and disappear rapidly during cycling but induce local bond weakening that facilitates irreversible TM migration[36]. Such migration can result in alternating TM-rich and dimer-rich domains, which finally cause voltage hysteresis between charge and discharge profiles. This directly links rapid anionic redox to slower cationic rearrangements, establishing a structure-property relationship between oxygen activity and electrochemical hysteresis. The voltage hysteresis issue was also studied by computational analysis. Reitano et al.[37] used DFT and Monte Carlo simulations to analyse Li2yTiyNi2−3yO2 compounds, and found that voltage hysteresis is intrinsic to the DRX lattice and arises from kinetically trapped TM migration, which is exacerbated by disordered local environments. These findings emphasise that structure-driven redox behaviour cannot be decoupled from lattice dynamics, and that the cation framework must be properly designed to enable stable oxygen redox. Therefore, optimising the electrochemical performance of DRXs requires careful structural control, including the balancing of lithium excess, cation disorder, and redox-inactive d0 TMs. These design levers influence not only Li-ion transport but also the reversibility of redox reactions and the structural reversibility during cycling. Thus, the electrochemical properties of DRX cathodes are intimately rooted in their atomic-scale structural motifs, highlighting the importance of a structure-driven design strategy. Therefore, to achieve high performance, an effectively balanced design is required. For example, Li excess (to secure percolation) with the identity/amount of redox-inactive d0 cations (to stabilise disorder and moderate O-redox), and suitable oxygen reactivity without compromising transport can give the promising results[38]. In practice, this balance governs not only ionic conductivity and rate but also redox reversibility and structural reversibility over cycling, thereby tying observed voltage hysteresis, impedance growth, and capacity retention directly to atomic-scale motifs (0-TM fraction, Li–O–Li frequency, and local TM coordination)[24,32,36,38,39].

-

Despite their potential for high capacity and compositional flexibility, irreversible oxygen loss and short-range ordering (SRO) are the major barriers hindering the high-rate capability and long-term cycling stability of DRX cathodes. Firstly, DRXs commonly suffer from oxygen loss, particularly during high-voltage charging when lattice oxygen participates in redox reactions. This will cause 0-TM channels to collapse, introducing kinetic barriers that significantly reduce capacity and stability[40]. Secondly, the SRO disrupts the ideal randomness needed for a fully percolating 0-TM Li-ion diffusion network. As a result, both rate performance and capacity utilisation are limited[41,42]. These factors will be discussed in detail in the following sections.

O redox and O loss in the DRXs

-

O redox is the key contributor to the high capacity of DRX cathodes, particularly those with excess lithium. As previously discussed, lithium excess is essential for stabilising the cation-disordered structure, but it also alters the redox chemistry and structural dynamics of DRXs. On one hand, excess lithium is necessary to stabilise the disordered structure and to create sufficient 0-TM percolation pathways. However, lithium excess also reduces the proportion of transition metals (TMs), thereby limiting the total TM redox capacity. On the other hand, Li-excess DRXs exhibit unique linear Li–O–Li configurations that are not present in conventional layered oxides[11,43]. These structural configurations play a critical role in activating oxygen redox. In DRXs, the lack of strong hybridisation between TM 3d and O 2p orbitals means that oxygen 2p states can lie at higher energy than the unoccupied TM d states, especially in Li-rich compositions[40,44]. As a result, during charging, oxidation can occur at the oxygen sites rather than the TM sites. This mechanism is known as non-bonding O redox and is particularly active in Li–O–Li configurations. As the lithium content increases, the number of such configurations rises, making the O redox more dominant. In some DRX systems, oxygen redox enables capacities that exceed the limit of TM redox alone[44].

While this O redox behaviour enables remarkable capacity, it is often coupled with irreversible oxygen loss, particularly at high voltages. During deep delithiation, lattice oxygen can be oxidised to O2 and released from the surface, resulting in TM-rich, densified surface layers[45,46]. This densification reduces the effective Li content and disrupts 0-TM percolation pathways, hindering long-range lithium transport. Consequently, the cathode experiences voltage hysteresis, increased polarisation, and rapid capacity degradation. Furthermore, the released oxygen can react with electrolyte species, leading to the formation of resistive interphases that increase cell impedance and accelerate performance fade.

As O redox and O loss are key in DRX's electrochemical behaviour, understanding and controlling them become critically important. Traditionally, oxygen loss in Li-rich cathodes has been considered irreversible. However, recent studies revealed a more complex picture: oxygen ions on the DRX surface and in the bulk have different behaviours[47]. Oxygen release is primarily localised at the surface, while in the bulk, oxidised oxygen species (molecular O2 and peroxo-like dimers) can remain trapped within the lattice and participate in reversible redox reactions. This emerging model offers a new perspective that oxygen redox may be partially reversible if oxygen species are confined to the bulk and their local environment is stabilised via proper structural design.

Short-range ordering (SRO)

-

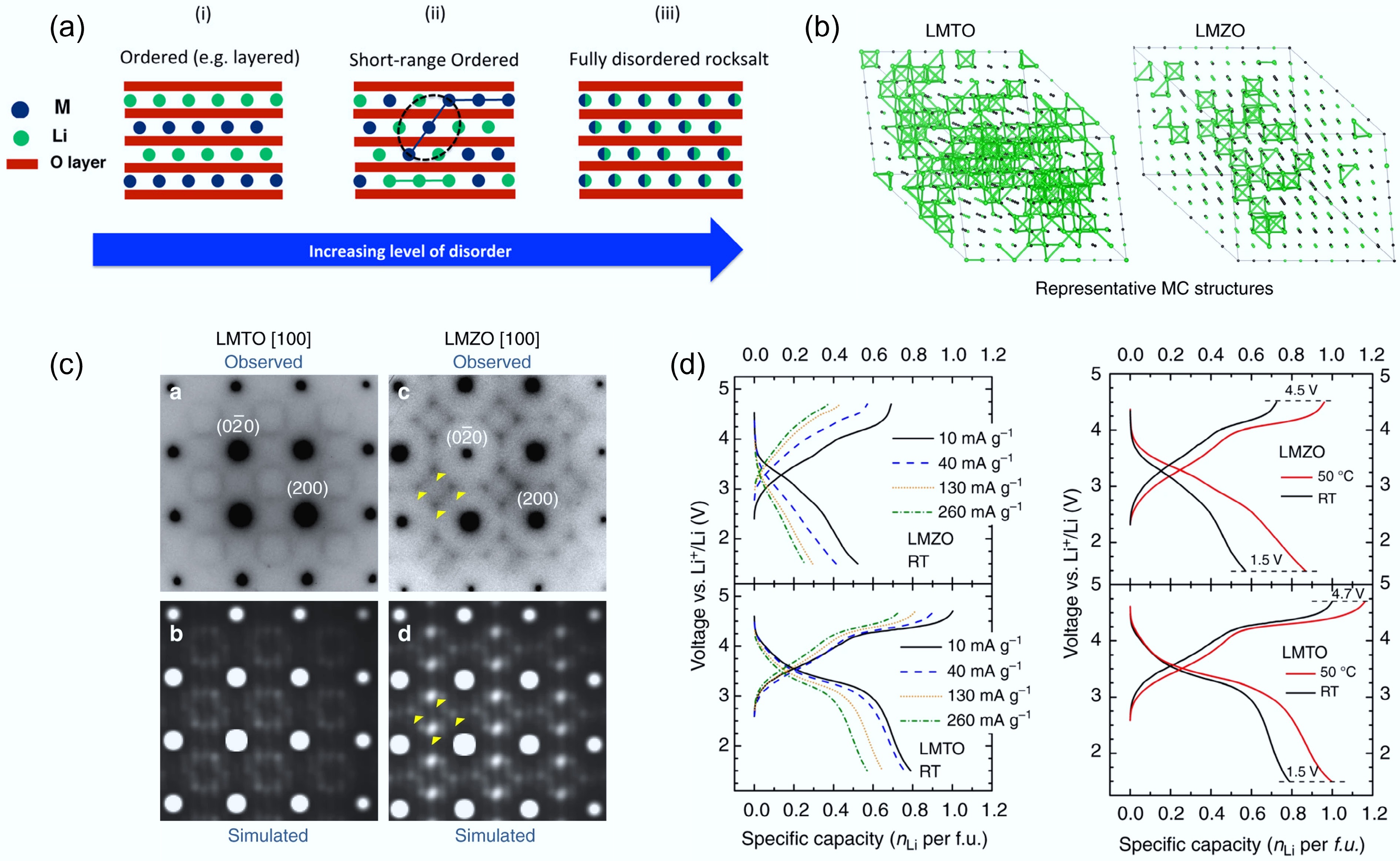

In addition to oxygen loss, short-range order (SRO) is another critical factor limiting the electrochemical performance of disordered rocksalt (DRX) cathodes. SRO is correlated with cation arrangements over only a few interatomic spacings. Although DRXs are nominally defined by a random distribution of Li+ and transition-metal ions on the cation sublattice, recent studies have revealed that local SRO can persist even within a globally disordered structure. As shown in Fig. 6a, SRO typically spans only a few atomic distances or nanometers. It is therefore invisible to conventional X-ray diffraction but can be directly observed using advanced electron diffraction techniques[48,49]. For instance, Kan et al.[42] investigated Li1.3Nb0.3Mn0.4O2 single crystals by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), where characteristic superlattice-like diffraction patterns along the [110] zone axis were observed across the entire particle. Such patterns are typical signatures of SRO and are reminiscent of those reported in non-stoichiometric transition-metal carbides and nitrides that also adopt rocksalt-type frameworks.

Figure 6.

(a) Illustration of the SRO structure. Reproduced with permission, Copyright © 2016 American Chemical Society[49]. (b) TEM images of LMTO and LMZO that visualise SRO. (c) Representative 0-TM channels in LMTO and LMZO. (d) Rate capability tests of LMTO and LMZO. Reproduced with permission, Copyright © 2024, Springer Nature[31].

As discussed before, Li transport in DRX structures relies on a percolating network of 0-TM tetrahedral hops that avoid TM neighbours, while SRO can influence both the population and connectivity of this network. Kan et al. computationally simulated three typical Li-ion percolation network models with different levels of local SRO. The yellow isosurfaces mark conduction paths through empty tetrahedral (8c) sites. Due to strong Li-TM electrostatic repulsion, MnO6 and NbO6 octahedra do not allow low-energy Li diffusion pathways. According to the simulations in different lattice planes, cation clustering or segregation (i.e., SRO) in the local structure can disrupt the continuous Li percolation network within each plane, while the fully random atomic arrangement can enable a more uniformly connected Li percolation network. Therefore, a small amount of SRO in DRX structures can significantly impact the local Li-ion diffusion kinetics[42].

To experimentally understand the impact of SRO on Li-ion kinetics, Ji et al. systematically investigated two DRXs: Li1.2Ti0.4Mn0.4O2 (LTMO) and Li1.2Ti0.4Zr0.4O2 (LTZO) by a combination of TEM and Monte Carlo simulation[31]. The square-like diffuse scattering pattern in Fig. 6b marked by the yellow arrow, represents the presence of the SRO. Compared to the LTMO, the SRO pattern intensity of LTZO is more pronounced. The Monte Carlo simulations (Fig. 6c) further reveal that LTMO maintains a well-connected network of 0-TM Li diffusion pathways (green lines), while LTZO shows a fragmented percolation network due to stronger cation correlations. This disruption of the Li-ion percolation network can dramatically reduce ionic conductivity and lead to sluggish Li kinetics of DRX. Thus, LTMO shows higher capacity and rate performance compared to LMZO (Fig. 6d), aligning well with its more uniform 0-TM network and weaker SRO. These results demonstrate a direct correlation between SRO intensity and Li+ transport efficiency in DRXs, which is also supported by many other studies[50−52].

Table 1 summarises the capacity, capacity retention, and degradation rates of classic LIB cathode materials compared with typical DRXs exhibiting different extents of short-range order (SRO). It is clear that DRXs deliver significantly higher initial capacities than conventional layered or olivine materials, demonstrating their strong potential for high-performance LIB applications. However, DRXs still faces challenges in cycling stability. Among the key factors, SRO plays a critical role. SRO hinders Li-ion transport pathways in DRXs, thereby limiting long-term performance, while strategies that suppress SRO have been shown to enhance Li-ion mobility, enabling both higher capacity and improved cycling stability. The detailed review of these strategies will be discussed in the following sections.

Table 1. Comparison of capacity, capacity retention, and degradation rates over extended cycling between classic LIB materials and typical DRXs with different extents of SRO

Materials Initial capacity

(mAh g−1)Capacity retention

upon cycling (%)Degradation rate

per cycle (%)Ref. LiCoO2 180 97 (500th) 0.006 [19] LiNi0.8Mn0.1Co0.1O2 202 75.3 (200th) 0.1235 [53] Li1.2Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 257 92 (200th) 0.04 [54] Li1.2Mn0.54Ni0.13Co0.13O2 282.1 97.6 (100th) 0.024 [55] LiFePO4 159.2 97 (100th) 0.03 [56] Li1.2Mn0.4Ti0.4O2 (lower SRO) ~260 ~88.6 (10th) ~1.1 [31] Li1.2Mn0.4Zr0.4O2 (higher SRO) ~170 ~53.8 (10th) ~4.6 [31] Li1.2Mn0.55Ti0.25O1.85F0.15 (lower SRO) 313 ~90 (5th) ~2 [52] Li1.2Mn0.55Ti0.25O1.85F0.15 (higher SRO) 273 ~90 (5th) ~2 [52] Li1.2Ti0.4Mn0.4O2.0 (octahedron-type SRO) ~175 − − [50] Li1.2Ti0.2Mn0.6O1.8F0.2 (cube-type SRO) ~150 − − [50] Li1.3Mn3+0.4Ti0.3O1.7F0.3 (higher SRO) 220 ~90 (5th) ~2 [51] Li1.3Mn2+0.2Mn3+0.2Ti0.1Nb0.2O1.7F0.3 (medium SRO) 269 ~90 (5th) ~2 [51] Li1.3Mn2+0.1Co2+0.1Mn3+0.1Cr3+0.1Ti0.1Nb0.2O1.7F0.3 (lower SRO) 307 ~90 (5th) ~2 [51] -

Compared with conventional layered cathodes, the composition design of DRX is markedly more flexible because the disordered rocksalt lattice can tolerate a wide range of cationic and anionic substitutions. As discussed earlier, the relative fractions of lithium, redox-active transition metals, redox-inactive d0 cations, and anions (O/F) jointly determine the transport pathways, redox partitioning, and structural stability of DRXs.

One of the key design factors is the Li/TM ratio, which affects both capacity and stability. Increasing lithium content enhances the formation of Li–O–Li environments and 0-TM channels for lithium-ion transport, but simultaneously reduces the proportion of redox-active TMs. This shift enhances oxygen redox contributions but also increases the risk of irreversible oxygen loss. In contrast, TM-based redox is generally more reversible and structurally stable. Therefore, careful tuning of the Li/TM ratio is essential to balance TM and oxygen redox contributions for optimal performance.

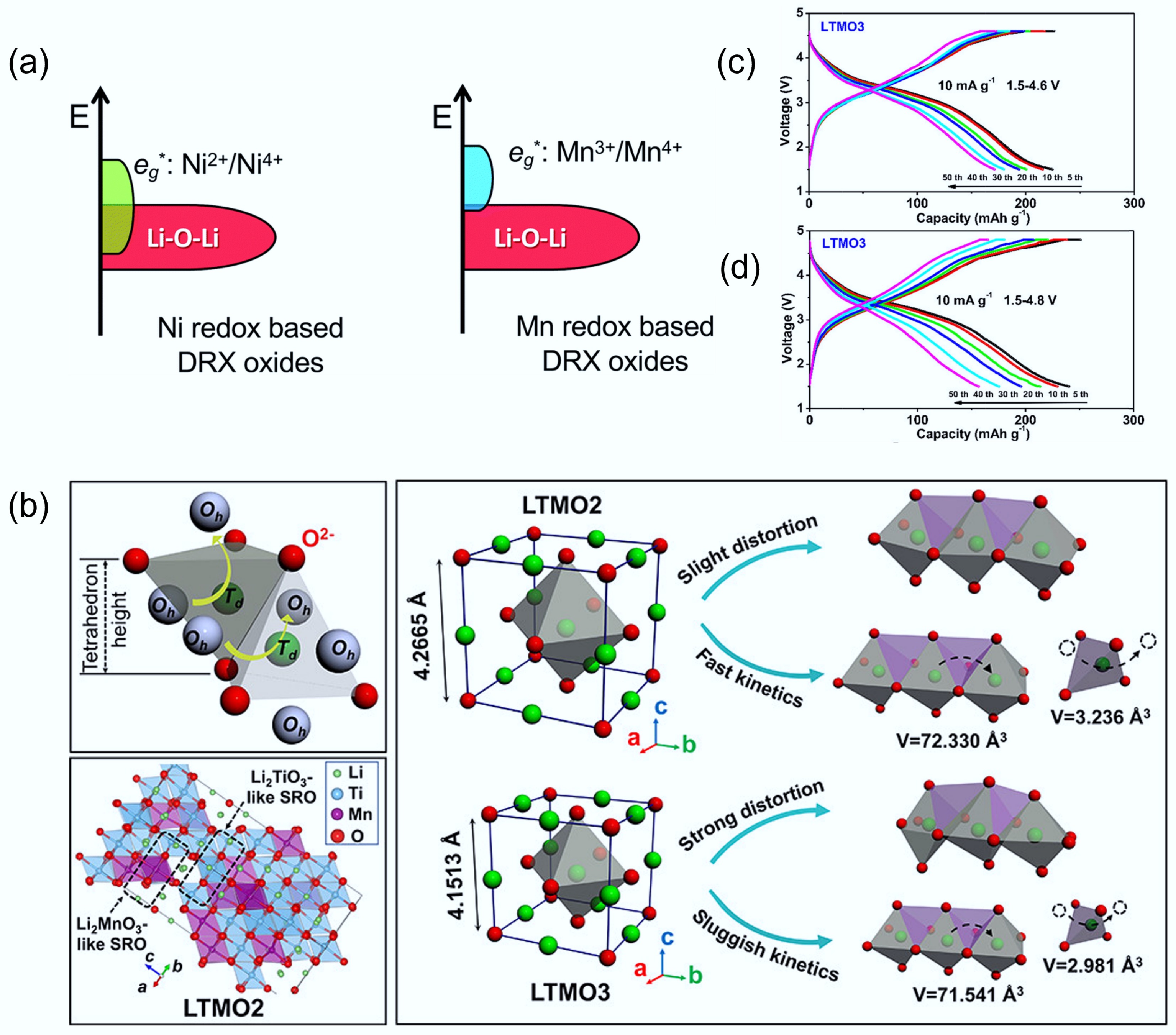

As for the selection of TMs, firstly, to boost capacity while retaining stability, multi-electron redox-active TMs such as Mn2+/Mn4+, Ni2+/Ni4+, and Mo3+/Mo6+ are commonly employed[8]. Secondly, the selection of d0 ions is also critically important for DRXs. However, the selection of TM can fundamentally influence the redox and performance of DRXs. For example, Fig. 7a shows the electronic energy level diagrams for Ni-based and Mn-based DRXs, in which Ni and Mn orbitals have different overlapping extent with Li-O-Li unhybridized orbitals. As Ni eg* orbitals and Li–O–Li orbitals are significantly overlapped, Ni-based DRX will promote oxygen redox and cause irreversible O2 release from the lattice[11]. Tang et al. used stoichiometry d0 ions to lower the redox-active TMs ratio, then added the two-electron redox Mn2+/Mn4+ to balance the electronic environment[57]. They compared the crystal structure, Li diffusion, and specific capacity of Li1.2Ti0.6Mn0.2O2 (LTMO2, Mn2+/Mn4+), and Li1.2Ti0.4Mn0.4O2 (LTMO3, Mn3+/Mn4+), respectively. DFT calculations revealed that LTMO2 has a significantly lower Li+ migration barrier (0.81 eV) than LTMO3 (1.27 eV), correlating with larger local O4 tetrahedral volumes and weaker Mn–O bonding in LTMO2. Indeed, the O4 tetrahedron volume of LTMO3 is smaller than that of LTMO2. In addition, the higher ratio of Ti4+ cations of LTMO2 leads to stronger Ti−O bonds, resulting in a more stable structure. Figure 7b illustrates that compared to LTMO3, LTMO2 shows a slight distortion, which corresponds to the fast kinetics. Indeed, the capacity and cycling stability of LTMO2 are better than those of LTMO3 (Fig. 7c & d), further highlighting the importance of oxidation state control in DRX design. In addition to adjusting the ratio of redox-inactive d0 cations, selecting suitable d0 redox-inactive cations also plays a crucial role. These cations do not directly contribute to capacity, but act as 'redox modulators' by stabilising the disordered lattice, suppressing oxygen loss, and tuning the local electronic environment[29].

Figure 7.

(a) Electronic energy level diagrams of Ni-based and Mn-based DRX materials. Reproduced with permission. Copyright © 2020, Royal Society of Chemistry[11]. (b) Schematic diagram of the structural distortion and Li+ diffusion process in LTMO2 and LTMO3. Voltage profiles of (c) LTMO2 and (d) LTMO3, respectively. Reproduced with permission, Copyright © 2022 American Chemical Society[57].

A further advantage of DRX materials over layered oxides is their tolerance to both cationic and anionic substitution due to inherent local chemical inhomogeneity. Disordered environments naturally generate Li-rich and TM-poor regions, which can accommodate high levels of anion doping, such as fluorine substitution into the oxygen sublattice. In contrast to layered materials, which can dope limited fluorine (F−), DRXs can support bulk-level F− incorporation, enabling enhanced structural and interfacial stability. In addition, to improve conductivity, stabilise the cation disorder structure and control SRO and O loss in DRXs, researchers try to introduce dopants like metal cations (Mg2+, Mo6+, Nb5+, etc.)[58−60] and anions like F−, Cl−, etc. to DRX structures[38,61]. Table 2 summarises the performance of DRXs with different compositions, showing their excellent elemental tolerance.

Table 2. Summary of representative DRXs with various d0 transition metals

Materials Capacity

(mAh g−1) (1st cycle charge/

discharge)Retention

compared to

the first

dischargeVoltage

range

(V)Ref. Li1.2Mn0.4Ti0.4O2 ~260/~240 67% (50th) 1.5–4.8 [57] Li1.3Nb0.3Mn0.4O2 350/~300 54% (20th) 1.5–4.8 [15] Li1.3Ta0.3Mn0.4O2 315/250 30% (30th) 1.5–4.8 [62] Li1.2Ti0.4Mo0.4O2 136/275 85% (30th) 1.0–4.0 [63] Li1.08Fe0.76Ti0.16O2 ~60/~35 − 2.2−4.5 [64] Li1.2Cr0.4Mn0.4O2 −/387 − 1.5–4.8 [65] LiNi0.5Ti0.5O2 161.1/118.6 67% (50th) 1.5–4.5 [66] Li1.25Fe0.5Nb0.25O2 ~290/250 [67] Li1.2Nb0.2Mn0.6O2 310/269 84% (30th) 1.5–4.8 [61] LiNi0.5V0.5O2 −/264 57% (50th) 1.3–4.5 [68] Li1.9Mn0.95O2.05F0.95 291/283 57% (50th) 2.0–4.8 [69] Li1.2Mn0.45Ti0.35O1.95F0.05 −/255 75.65% (20th) 1.5–4.8 [70] Li2Ti0.5V0.5O2F −/285 81% (25th) 1.3–4.1 [71] Overall, the most reliable composition is to keep Li only modestly above the percolation threshold with a suitable fraction of d0 cations, thereby stabilising disorder and lowering migration barriers without interrupting TM redox. For TM selection, Mn-rich, Ti-assisted chemistries are attractive due to their earth abundance and robust crystal structure. In contrast, Ni or Mo can be added to adjust rate capability, stability, and capacity. For the anion, a moderate and composition-specific F is preferred to temper oxygen activity and improve interfaces. As the composition of DRX is very diverse, a standardised study and reporting is suggested. To achieve this goal, reporting of a data package containing cycling performance, percolating Li fraction, voltage-hysteresis area, gas evolution, and interfacial resistance growth is highly recommended.

O loss control

F substitution to prevent oxygen oxidation and oxygen release

-

Although oxygen redox enables the high specific capacity of DRX cathodes, it also introduces problematic irreversible oxygen loss during cycling. Upon deep delithiation at high voltage, lattice oxygen is oxidised and can escape the structure as molecular O2 or react with the electrolyte. This oxygen loss leads to local chemical instability, surface densification, and structural collapse, which together cause rapid voltage fade, poor reversibility, and loss of capacity. To suppress O loss, one promising strategy is the partial substitution of oxygen with F− in the anion sublattice. Fluorination has been shown to improve the cycling stability of DRX materials by reducing the oxidative driving force on oxygen anions, stabilising the lattice, and suppressing irreversible O2 release[40,72,73].

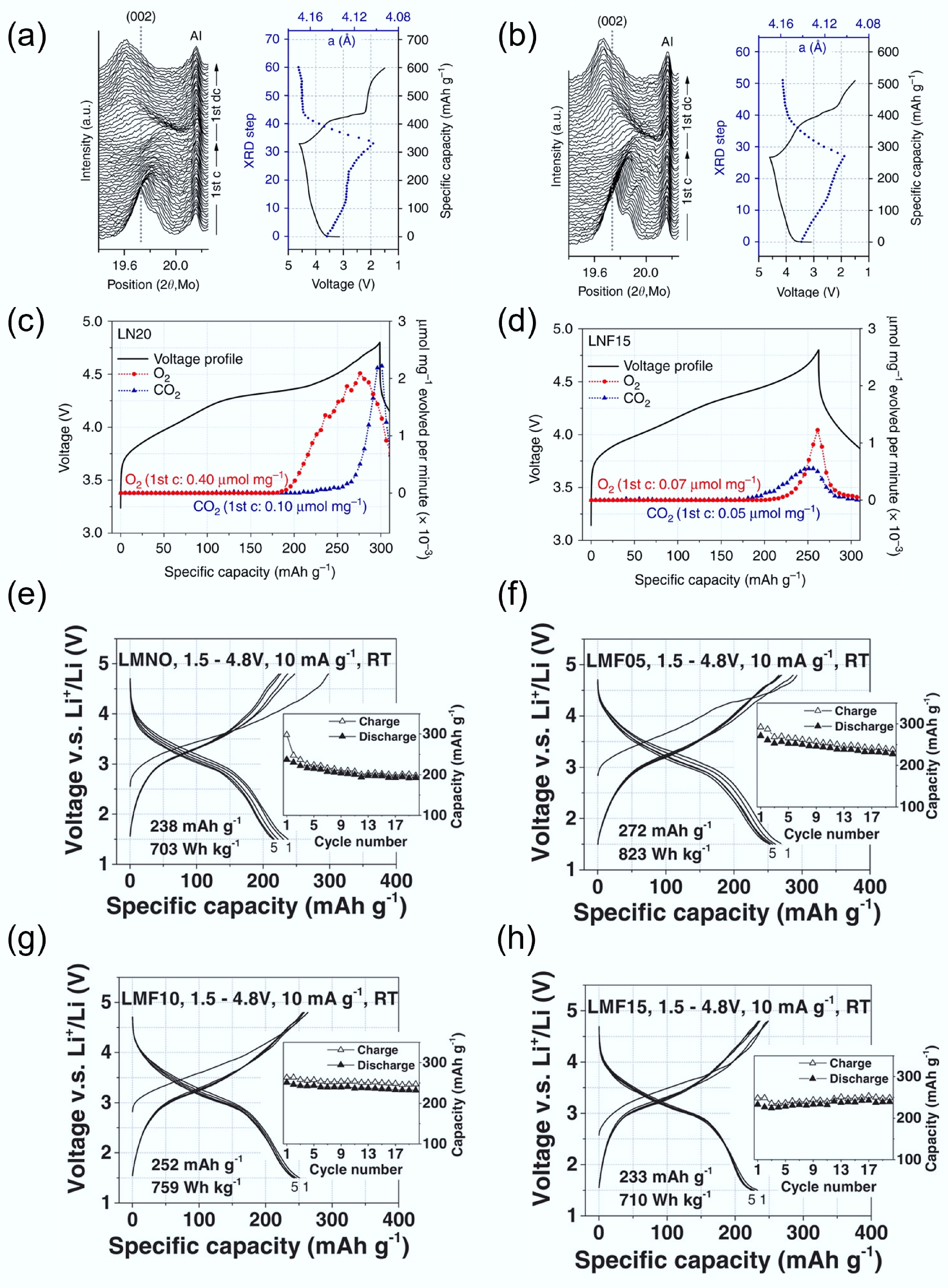

Lee et al. investigated the electrochemical properties of a non-fluorinated Li1.2Ni0.333Ti0.333Mo0.133O2 (LN20), and a fluorinated counterpart Li1.15Ni0.45Ti0.3Mo0.1O1.85F0.15 (LNF15)[40]. In the in situ XRD patterns (Fig. 8a & b), both materials showed a shift of the (002) diffraction peak to higher angles during charging, indicating lattice contraction due to delithiation. However, the degree of lattice change was smaller in LNF15. After the first full cycle, the net increase in lattice parameter was +1.24% for LNF15, compared to +1.87% for LN20. This difference suggests that LNF15 undergoes less structural reorganisation, confirming improved reversibility and lower oxygen loss. To further support this, differential electrochemical mass spectrometry (DEMS) results in Fig. 8c & d reveal significant O2 evolution from LN20 after ~185 mAh g−1 of charge, whereas LNF15 released significantly less O2. The timing of gas evolution matched the plateau in XRD peak movement, indicating that oxygen loss is tied to structural stagnation and lattice instability. The initial O2 release may occur via intermediate reactions forming Li2O or Li2O2 before full oxygen gas evolution, highlighting the importance of structural suppression strategies like fluorination.

Figure 8.

In-situ XRD during initial cycling of (a) LN20 and (b) LNF15. In situ DEMS results on O2 and CO2. (c) LN20 and (d) LNF15. Reproduced with permission, Copyright © 2017, Springer Nature[40]. Charge/discharge curve of (e) LMNO, (f) LMF05, (g) LMF10, and (h) LMF15. Reproduced with permission, Copyright © 2018 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim[74].

Lun et al.[74] further investigated the effects of fluorine substitution by systematically varying the F content in a Mn3+-Nb5+-based DRX system. They prepared three fluorinated DRX materials: LMF05 (2.5% F), LMF10 (5%), and LMF15 (7.5%). As shown in Fig. 8e, the voltage profile of the unfluorinated LNMO displayed significant polarisation and a large gap between charge and discharge curves, indicative of poor reversibility. In contrast, F-substituted samples in Fig. 8f–h showed progressively smaller polarisation and better cycling retention with increasing F content. Moreover, they observed higher CO2 evolution in LNMO during high-voltage cycling, suggesting more severe electrolyte decomposition, likely triggered by reactive oxygen species. In contrast, the F-containing samples showed suppressed CO2 generation, further confirming that fluorination stabilises the oxygen redox process and suppresses parasitic reactions. However, they also noted that excessive fluorination can slightly reduce long-term capacity retention due to the reduced participation of oxygen redox. This highlights the need to optimise fluorine levels to balance structural stability and energy density.

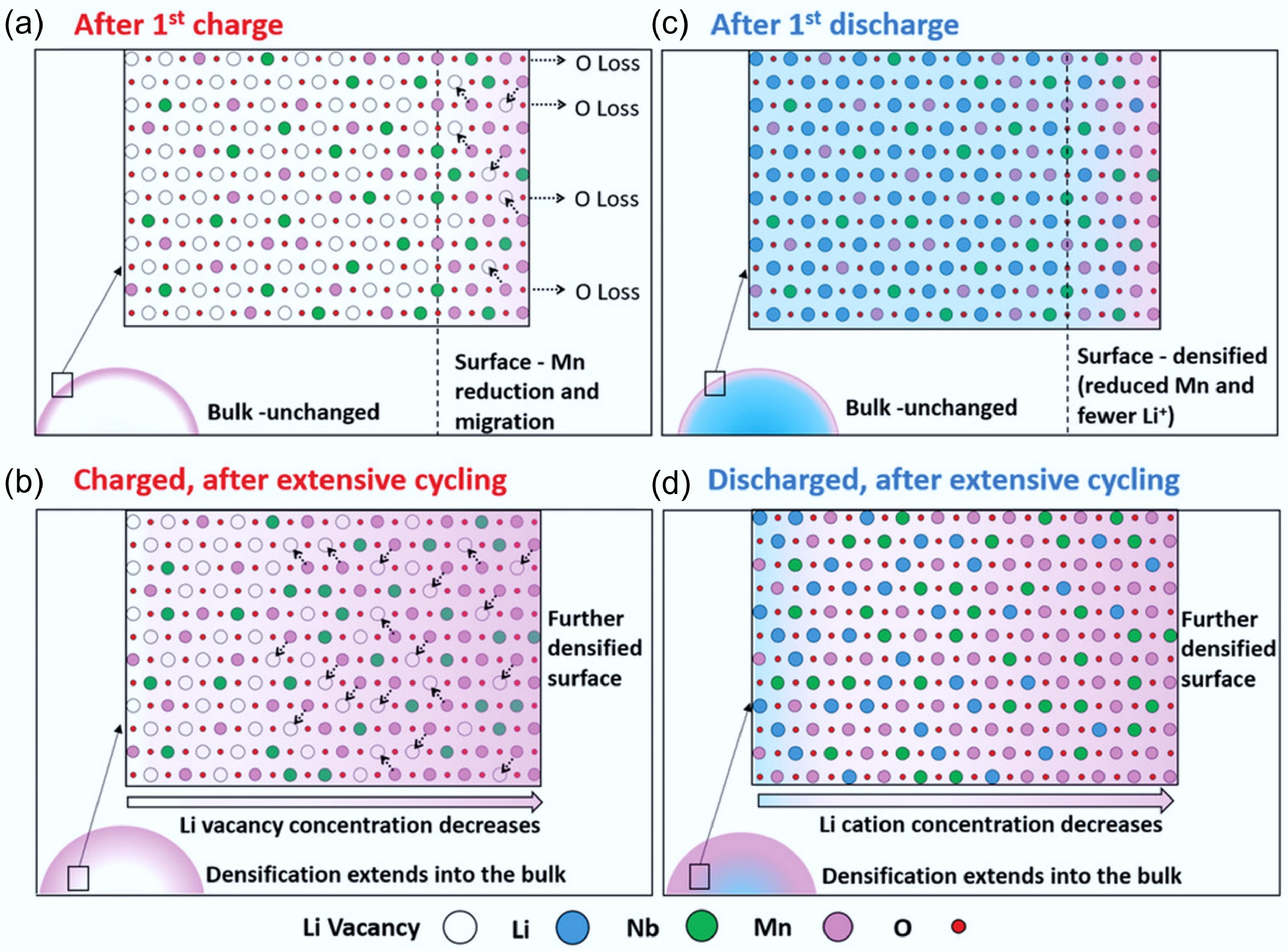

Despite the stabilising effects of F substitution, degradation still occurs in fluorinated DRX (F-DRX) cathodes due to coupled structural changes in both the cationic and anionic sublattices. Chen et al.[34] proposed a 'concerted-densification' degradation mechanism, wherein oxygen loss leads to Mn reduction and migration, followed by surface densification and Li-site loss. As shown in Fig. 9a–d, after the first charge, surface oxygen loss leads to the formation of oxygen vacancies, which in turn destabilise high-valent Mn4+ cations. These are reduced to Mn3+ and migrate into lithium sites, causing structural densification. During discharge, although Li+ is reinserted into the bulk, the surface remains Li-deficient, impairing lithium percolation and increasing resistance. This can result in a Li concentration gradient, with reduced Li content at the surface due to irreversible cation migration and structural distortion. Over successive cycles, this degrades the original 0-TM percolating network, impairing electrochemical performance[45,75]. Recent research presents the concerted-densification model, in which not only cationic migration (Mn, Nb, Ti) but also F-anion redistribution leads to densification[35]. Fluorine tends to enrich at the surface and can form LiF-like domains, contributing to anion sublattice stiffening and reduced Li-ion mobility near the interface. This dual densification process underscores that while fluorination mitigates oxygen loss, it introduces new degradation pathways if not properly managed.

Figure 9.

(a)–(d) The degradation process of Li1.3Nb0.3Mn0.4O2 cathodes at different stages. Reproduced with permission, Copyright © 2019 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim [34].

In summary, the evidence shows that partial fluorine substitution is one of the few promising strategies that can directly suppress irreversible oxygen activity in DRXs. It can reduce the thermodynamic driving force for lattice-oxygen oxidation, impede O2 and CO2 gas evolution during high-voltage charging, and reduce the magnitude of cycle-induced lattice reorganisation. Recent research suggests fluorination is especially effective in Mn-based DRX systems. However, fluorination should be balanced, as excessive F can also influence useful anion redox or cause structure rearrangement. It is most beneficial to add more F at the surface or near-surface to stabilize the reaction interfaces, while maintaining a moderately fluorinated F content in the bulk to retain reversible O-redox and high TM redox capacity.

Interface engineering to suppress O loss

-

Controlling interfacial degradation is essential for enhancing the long-term cycling stability and safety of DRX cathodes. Although bulk oxygen redox contributes to capacity; the release of lattice oxygen at high voltages often triggers undesired interfacial reactions and structural damage. As reported in prior studies[62], oxygen release leads to surface enrichment of transition metals (TMs), resulting in densification. In most DRX studies, LiPF6-based liquid electrolytes in organic carbonate solvents are used. At high voltages, these electrolytes decompose upon contact with reactive cathode surfaces, forming high-resistance interphases that block Li+ transport and degrade performance[76]. Therefore, interface engineering strategies, particularly surface coatings, are critical for suppressing oxygen loss and improving interfacial stability in DRXs.

Surface coatings have been extensively used in layered oxide cathodes and are now being applied to DRXs to minimise electrolyte decomposition, suppress surface oxygen release, and mitigate transition metal migration. An effective coating should inhibit parasitic reactions without significantly increasing charge-transfer resistance or impeding ionic transport[51,59,77,78]. The study by Huang et al.[79] applied nanometer-scale Al2O3 coatings via atomic layer deposition (ALD) on Li1.2Ti0.4Mn0.4O2 (LTMO). By comparing the CV curves of LTMO and LTMO/Al2O3, two notable differences can be observed. Firstly, In LTMO/Al2O3, the anodic peak at ~4.63 V persisted through subsequent cycles, whereas it diminished in uncoated LTMO, suggesting reduced oxygen loss in the coated sample. Secondly, the cathodic peak near 3.17 V remained more stable in LTMO/Al2O3, indicating that Mn maintained a reversible Mn4+/Mn3+ redox process. In contrast, pristine LTMO exhibited a shift to lower Mn valence states (below Mn3+), consistent with oxygen vacancy-driven densification in the first cycle. These results confirmed that the Al2O3 coating stabilizes the cathode surface, suppresses oxygen evolution, and improves redox reversibility, thereby enhancing cycling performance.

Yu et al. compared the performance of Li1.2Ni0.3Ti0.3Nb0.2O2 (LNTNO20) after carbon coating in different C ratios (5:1,6:1,7:1, and 8:1)[51]. The LNTNO20@C (C-coating) shows higher discharge specific capacity and better rate performance than LNTNO20. After one cycle, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) tests were conducted on cathodes, specifically LNTNO20 and LNTNO20@C, to investigate their kinetic performance under different calcination temperatures[51]. The EIS measurements and the chosen equivalent circuit reveal the kinetic performance of the cathodes and can help understand the effects of calcination temperature on their electrochemical behaviour. Compared to LNTNO20, the lower Rs and Rct values of LNTNO20@C relate to the higher ionic conductivity and reflect that the carbon coating effectively limited side reactions between the DRX surface and electrolyte, thereby forming a thinner and more stable solid electrolyte interphase (SEI). In addition, the CV curve suggests that after carbon coating, LNTNO20@C shows lower polarisation and less O loss.

Collectively, current evidence shows that interface engineering is the most direct strategy to mitigate oxygen-triggered surface damage and irreversible oxygen loss in DRX. The most promising interface engineering is to chemically passivate reactive surface oxygen/TMs and maintain efficient Li+ transport across the interface, while overly thick or poorly conducting coating films can reduce the effectiveness by deteriorating reaction kinetics. Thus, a moderate-reactivity, Li-permeable coating in the 1–5 nm range, applied with high conformality and paired with electrolyte/fluorine strategies, is recommended to ensure high capacity and stable cycling. However, further investigation is needed to explore additional coating methods and materials in greater detail. To enhance the stability of the interface, another approach is to explore alternative high-voltage electrolyte systems as alternatives to LiPF6-based solutions, which will not be detailed here.

Short-range ordering (SRO) control

-

In DRX cathodes, lithium segregation can locally create accessible voids near redox-inactive d0 transition metals, which are essential for forming 0-TM diffusion pathways. However, numerous theoretical and experimental studies have shown that the overall effectiveness of Li-ion transport in DRX materials depends heavily on the degree of cation randomness throughout the lattice[41]. A more random distribution of Li+ and transition metal (TM) cations facilitates the formation of a percolating lithium migration network, which enables long-range Li+ transport and efficient electrochemical performance. Conversely, the presence of SRO can disrupt this percolating network. When TM and Li ions exhibit spatial preference or clustering, the availability of continuous 0-TM pathways is reduced, which impedes Li-ion diffusion. This decrease in ionic mobility can limit charge transport and reduce the rate capability and energy density of the cathode material[80]. Therefore, minimising SRO is critical for unlocking the full transport potential of DRX cathodes. Developing universal synthesis strategies that enhance cation disorder, such as high-entropy mixing, optimised cooling rates, or mechanochemical synthesis, can help suppress SRO and promote a more homogeneous cation distribution. By tuning these parameters, researchers can improve lithium percolation, ionic conductivity, and ultimately, the electrochemical performance of DRX-based lithium-ion batteries.

Fluorine (F) substitution

-

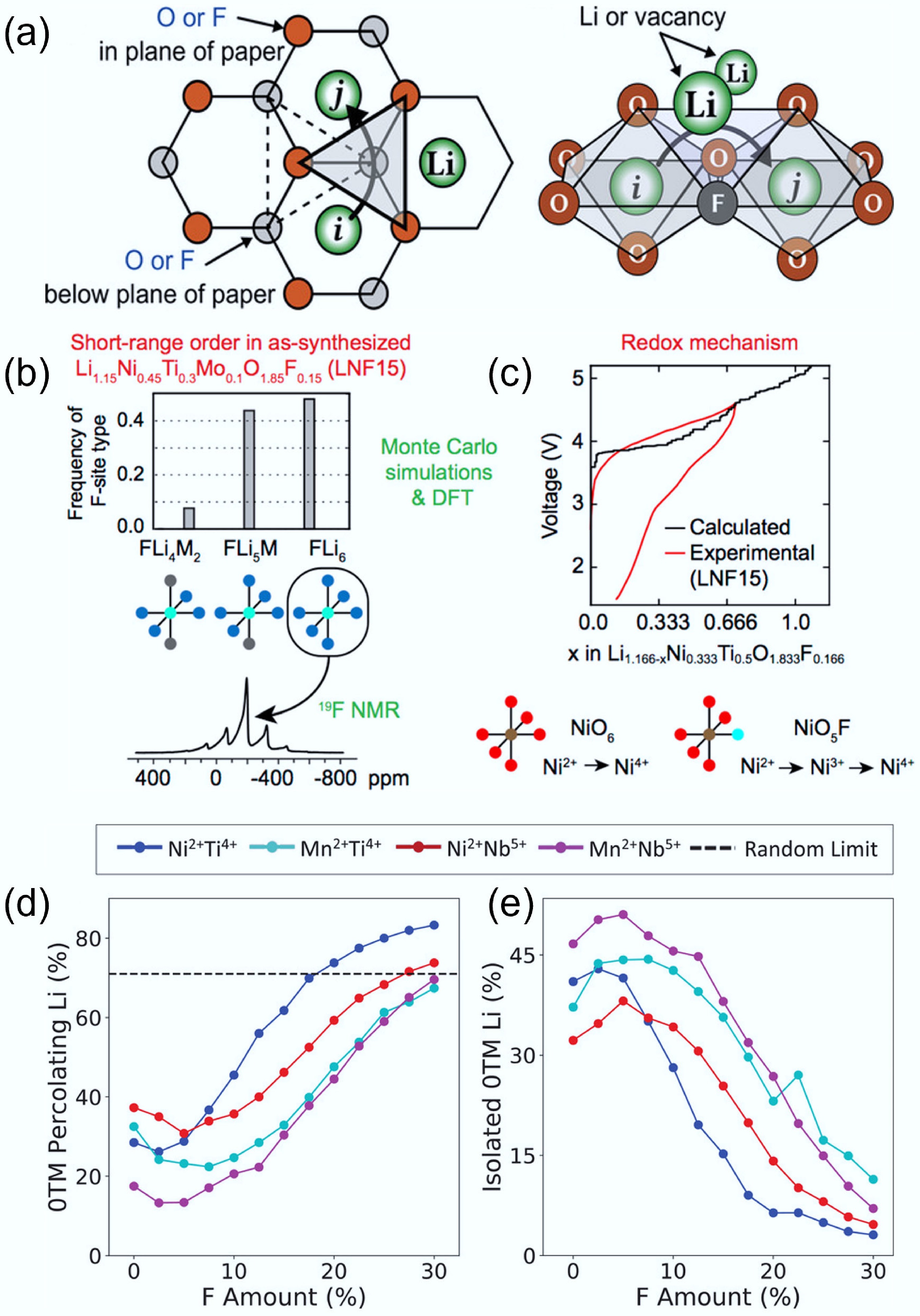

As previously discussed, substituting O2− with F− in DRXs can improve charge/discharge reversibility by lowering the driving force of anion-based charge compensation and suppressing irreversible O2 release, thereby reducing voltage hysteresis and surface densification[38]. In Ni-based oxyfluorides, operando and ex-situ spectroscopy further show simultaneous moderation of O-redox with preserved cationic redox, consistent with reduced gas evolution at high voltages[81]. Due to F's high electronegativity, F can form strong coordination with Li and reshape the SRO in the structure. Computation simulations on multiple DRX chemistries reveal that a sufficiently high F substitution content (≥ 15 at%) can increase 0-TM percolation regardless of composition, while the effect of low F levels is composition dependent and can either help or hinder percolation depending on the intrinsic properties of SRO[41]. These trends align with combined modelling–experiment studies showing that F reduces the share of anion-redox at high states of charge and stabilises the rock-salt lattice, aiding capacity retention[35]. As shown in Fig. 10a, substituting oxygen with fluorine leads to the formation of Li–F bonds that can modulate local cation environments and potentially reduce the activation energy for Li+ hopping[33]. With increasing fluorine content, the number of Li4 tetrahedra also increases (Fig. 10b & c), suggesting that fluorine can help suppress detrimental SRO and promote a more favourable Li+ migration network[20].

Figure 10.

(a) Influence of F substitution on 0-TM diffusion channel and o-t-o hopping mechanism. Reproduced with permission, Copyright © 2020 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim[33]. Evolution of local structure around (b) F and (c) Li. Reproduced with permission, Copyright © 2018 American Chemical Society [20]. Evolution of (d) 0-TM Li transport and (e) isolated 0-TM Li with the increasing content of F substitution. Reproduced with permission, Copyright © 2020 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim[41].

However, the influence of F substitution is not universally beneficial, as the Li accessibility can vary with the F substitution content (Fig. 10d & e)[41]. Owing to strong Li-F bonding, excessive fluorine can enrich Li to form local Li-rich clusters (such as Li6F or Li5MF structures), which will interrupt the well-connected 0-TM networks and degrade the Li transport, despite a higher local count of 0-TM environments[41]. High F content may also have solubility/segregation issues, causing F enrichment in the structure and consequences in performance deterioration[82−84]. For example, Monte Carlo simulations on the model structure Li1.166Ni0.333Ti0.5O1.833F0.166 showed that fluorine tends to segregate into regions with a high local concentration of Li. These F-enriched domains often have five to six Li+ ions as nearest neighbours, forming disconnected Li-rich clusters rather than an extended 0-TM percolation network. Such localisation undermines long-range lithium-ion transport and limits DRX's electrochemical performance[49]. In addition to bulk substitution, surface fluorination can stabilise the cathode/electrolyte interface without influencing the bulk Li percolation[11].

Therefore, F substitution is a potent but non-universal SRO controller for DRXs. Moderate F substitution can optimise SRO and enhance Li-ion mobility, while excessive fluorination may deteriorate the performance by inducing local inhomogeneity and percolation obstacles. To maximise the benefits of F doping, a moderate, composition-specific bulk F as a fine-tuner, and surface fluorination to stabilise the interface are recommended. In addition, it is worth noting that in Mn-rich DRX families, a careful F quantification is recommended, given the reported solubility and distribution limits. To achieve this goal, it is essential to systematically investigate its impact on SRO and Li distribution using both experimental characterisation and theoretical modelling. Identifying the material-specific optimal F content will be crucial for engineering DRX cathodes with both high stability and fast Li-ion kinetics.

Constructing high-entropy DRX structure

-

Beyond fluorination, high-entropy (HE) design by mixing multiple TMs in a single disordered rocksalt lattice has emerged as a powerful route to suppress SRO and thereby improve Li-ion transport and capacity in DRX cathodes. The HE concept was originally developed in metallurgy, which can stabilise a solid solution through high configurational entropy. As DRXs have high chemical flexibility, which allows for the incorporation of multiple TMs without compromising the rocksalt framework, the HE strategy is especially promising. Thus, this approach has been recently extended to DRX materials design, and increasing the number of TM species systematically weakens cation–cation correlations, reduces SRO signatures in electron diffraction, and correlates with higher energy density and rate capability at a fixed overall metal content[51].

In the experimentally constructed DRXs, the electron diffraction patterns of DRX samples containing two, four, and six TM species show square-like diffuse scattering features characteristic of SRO. As the number of TM species increases (higher entropy), the intensity of the diffuse scattering diminishes, indicating a progressive reduction in SRO. This confirms that increasing compositional complexity weakens the local cation–cation correlations, leading to a more disordered cation distribution and improved percolation pathways for Li+ ions. The electrochemical performance of these HE-DRX materials also supports this conclusion. Cathodes with higher entropy (more TM species) consistently exhibit higher discharge specific capacities. The enhanced performance is attributed to the more uniform cation distribution and better formation of 0-TM channels for Li+ diffusion. Thus, multi-element mixing is an effective strategy to suppress SRO, improve lithium transport kinetics, and enhance the capacity of DRX cathodes. Recent modelling studies further confirmed this finding and provided theoretical design principles. The simulation results suggest that modest changes to Li–F first-neighbour correlations slightly affect the amount of 0-TM motifs, whereas Li–Li second-neighbour correlations dominate the connectivity of those motifs and thus the percolation of Li pathways. Such simulation also indicates that higher configurational entropy (TM6 compared to TM4 and TM2) can lead to lower octahedral distortion, smaller charge-induced volume change, and a favourable distribution of redox participation, providing a structural rationale for improved cycling stability in HE-DRX (Fig. 11)[21].

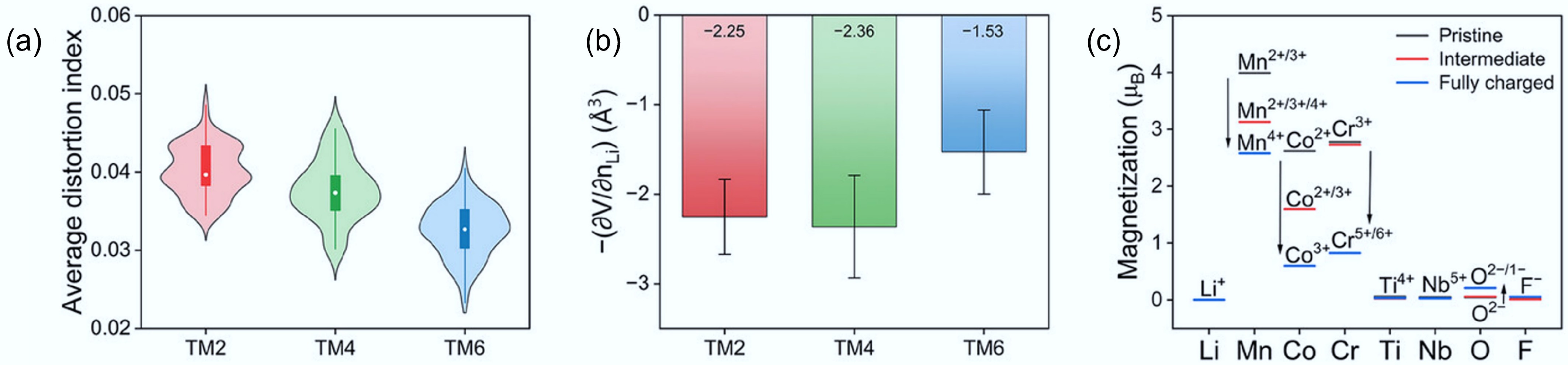

Figure 11.

(a) The average octahedral distortion index for DRXs with different entropy. (b) Partial molar Li-extraction volume during the first charge of these DRXs. (c) Element-resolved average magnetisations of these DRXs. Reproduced with permission, Copyright © 2025 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim[21].

However, simply increasing entropy without a suitable design cannot guarantee good performance. Recent cluster-expansion/Monte-Carlo studies indicate that the effectiveness of HE on SRO suppression depends sensitively on Li excess and F content. The entropy-driven SRO suppression is strongest when the base composition already supports 0-TM formation (near or above the percolation threshold) and is aided by moderate fluorination. But when this prerequisite is not achieved, simply 'adding more elements' can give diminishing or non-monotonic returns, or even fragment percolation if Li–Li correlations are pushed away from a favourable energy region. These results suggest a synergic co-design of HE-DRX and Li/F[23].

Building on the above threads, constructing a High-Entropy DRX structure is an effective way to improve performance, given it is properly controlled. Multi-element mixing is most effective when used as a fine-tuner alongside Li-excess and anion chemistry. Firstly, HE can suppress SRO, promote the percolating 0-TM network, and increase reversible capacity, while well-chosen d0 cations can help stabilise the lattice structure and oxygen redox. When coupled with moderate F and careful control of Li–Li correlations, this strategy can lead to HE-DRX compositions with lower effective migration barriers, reduced lattice breathing, and improved capacity retention.

Phase control and partial disordered structure construction

The advantages of the partial disordered phase in DRXs

-

Before 2014, high-performance Li-ion cathodes relied on ordered oxides—layered LiMO2 and spinel cathode materials. Researchers believed that distinct Li and transition-metal (TM) sublattices were required for fast diffusion and stable cycling. In 2014, Urban et al. challenged this view[30]. They showed that Li-excess cation-disordered rock-salt (DRX) oxides also deliver high capacity and rate capability. Their density-functional and percolation studies revealed that a network of Li-only (0-TM) tetrahedral pathways forms when Li : TM ≈ 1.09. This network enables efficient Li transport in Li1+xTM1−xO2 (x ≈ 0.09). Experimentally, Li1.21Mo0.467Cr0.3O2 achieved ≈300 mAh g-1, confirming the promising future of DRXs. After this, DRXs cathodes have emerged as a particularly promising class of Li-ion battery materials, owing to their combination of high theoretical capacity, earth-abundant constituents, and intrinsic structural flexibility. However, achieving both high capacity and rapid Li-ion transport in DRX oxides typically requires engineering of the cation sublattice to balance disorder (for Li-excess percolation) against local order (for low-barrier migration pathways).

A breakthrough insight from the Ceder's group introduced the concept of in situ formation of a partially ordered spinel-like phase ('δ phase') within the DRX matrix, demonstrating that even nanoscale spinel domains can dramatically enhance electrochemical performance by increasing the density of zero-transition-metal (0-TM) channels for Li transport[85,86]. Atomic-resolution STEM and nanodiffraction showed that mild delithiation and low-temperature annealing produce ~3–7 nm partially ordered spinel regions separated by antiphase boundaries. These domains boost performance by increasing 0-TM pathways and converting two-phase spinel reactions into solid-solution behaviour. The result is smoother voltage profiles, higher rate capability, and reduced voltage fade over hundreds of cycles. Together, these findings highlight a dual approach: long-range disorder in DRX provides abundant percolation channels, while local spinel order offers low-barrier diffusion and continuous lithiation. The δ-phase concept extends the original DRX idea by creating coherent spinel clusters without full phase separation. This synergy delivers high capacity, excellent rate performance, and stable cycling in earth-abundant oxide cathodes.

Synthesis routes to engineer partial disordered phase control

-

Although the δ phase forms spontaneously under thermal or electrochemical driving forces, deliberate control over its nucleation and distribution requires a thoughtful choice of synthesis methods[86]. Synthesis is the foundation of materials development, yet tailoring the microstructure of multiphase systems remains difficult, especially when the desired phases are metastable. Achieving precise phase control demands both thermodynamic insight and mastery of kinetic pathways. Recent progress in real-time synthesis monitoring and first-principles modelling has clarified how processing conditions affect reaction routes, enabling access to non-equilibrium phases and finer control over local structure and properties.

Traditional DRX synthesis involves mixing oxide precursors (such as Li2CO3, MnO2, TiO2) via mechanical milling, followed by annealing at 800–1,000 °C. Patil et al. demonstrated that sol-gel-derived stoichiometric mixing can be adapted to solid-state DRX, yielding Mn-rich DRX compositions with short-range cation order[87]. However, in purely solid-state routes, promoting δ-phase formation often requires post-annealing under carefully controlled cooling rates: rapid quenching can kinetically trap spinel domains, whereas slow cooling tends to favour fully randomised cation arrangements. Careful tuning of annealing temperature, dwell time, and cooling profile thus enables partial spinel ordering without extensive phase segregation.

High-energy ball milling can induce metastable phases at relatively low temperatures, including oxyfluoride DRX materials. Blumenhofer et al. showed that[88] mechanochemical synthesis yields Li2Mn1–xVxO2F (0 ≤ x ≤ 0.5) with embedded spinel-like clusters that can enhance Li-ion transport. However, large defect concentrations and poor crystallinity often necessitate subsequent annealing to develop coherent δ domains. Recent advances in mechanochemical protocols aim to achieve milder milling conditions paired with brief thermal treatments to nucleate spinel phases while preserving nanoscale particle sizes, striking a balance between kinetic activation and structural coherence. Sol-gel synthesis provides atomic-scale precursor mixing and offers greater control over morphology and defect distributions. Chen et al. demonstrated that selective carboxylate chelation in a sol-gel route enables precise phase control in Li-excess cation-disordered rocksalt cathodes[89]. By tuning chelator strength, the approach directs defect distributions during precursor gelation, which in turn governs the in situ formation and coherence of spinel-like domains within the disordered matrix. The result is a controlled balance of disorder and local ordering that optimises 0-TM Li-percolation networks and significantly improves electrochemical performance. Similarly, Patil et al. reported[87] that sol-gel–derived Mn-rich DRX materials form cation-ordered clusters at moderate temperatures (≈800 °C), leading to enhanced capacities (~275 mAh g−1), and improved cycling stability compared to solid-state analogues. Solution methods also allow incorporation of fluorine or other dopants to further stabilise spinel domains and tune redox chemistry. Moreover, proton-exchange activation offers an alternative phase-control route[90]. Mild acid treatment followed by annealing at 350 °C induces H+–Li+ exchange in Mn-rich DRX, nucleating ~7 nm spinel-like domains without pulverizing the particles. This scalable method embeds local spinel order within the disordered matrix, substantially enhancing Li-ion mobility and overall cathode performance.

According to these reported synthesis routes, partial ordering is most effective when it exists as nanoscale, spatially controlled, and easily reversible nano-domains, rather than growing into large, rigid phases. Specifically, δ-like spinel motifs that remain coherent, are ~3–7 nm in size, well dispersed, and reversible under operating conditions are a promising combination.

To achieve this condition, the synthesis should start with highly mixed precursors (such as sol-gel or carefully controlled solid state), then apply brief sub-eutectic anneals with controlled cooling for δ-domain nucleation without coarsening, followed by short and low-temperature defect-healing treatments to develop a coherent phase. Materials featuring a δ-enriched surface and a DRX-enriched core may have higher interfacial kinetics with bulk percolation. Altogether, these synthesis strategies demonstrate that careful manipulation of thermodynamics and kinetics can reliably produce DRX-spinel composites with enhanced Li-transport networks, paving the way for earth-abundant cathodes that deliver both high capacity and stable, high-rate performance. To fully understand the synthesis-performance relationships, computational simulations of viable nucleation windows and in-situ/operando monitoring of phase evolution, together with crystal and electrochemical characterisation, are recommended for future research. With these guidelines, partially ordered DRX can evolve into a designable microstructure that delivers high battery performance.

-

DRX cathode materials have emerged as one of the most promising directions for high-energy lithium-ion batteries due to their high theoretical capacity, lack of dependence on expensive transition metals, and broad compositional tolerance. However, their practical application is still hindered by irreversible oxygen loss that drives TM migration, voltage decay, and surface densification under deep delithiation, and short-range cation ordering that impedes the 0-TM percolation needed for fast, long-range Li transport. These bottlenecks are closely related to several critical factors, including Li excess, d0 TM selection/content, and anion chemistry, underscoring that the rational structure and composition design are keys to high-performance DRXs. From this perspective, several promising strategies emerge. Firstly, adjusting the fractions of lithium and the selection of active/inactive TMs can fundamentally tune the lithium-ion transport and oxygen redox of DRXs. Secondly, moderate fluorine substitution can reduce the driving force for O loss and help stabilise the disordered lattice without sacrificing the 0-TM network. Thirdly, interface engineering, such as coatings, can suppress side reactions at high voltage and reduce the irreversible oxygen loss. Fourthly, high-entropy construction can prevent local cation–cation correlations to limit SRO. Finally, phase-engineering that provides nanoscale δ-phase motifs can enable low-barrier Li diffusion pathways while retaining high-quality 0-TM percolating channels. Together, these approaches provide a coherent guideline towards both oxygen stability and Li-ion kinetics in DRXs.

Building upon the above approaches, we believe that the most reliable strategy for high-performance DRX is a synergetic co-design rather than a single-knob optimisation. Promising design principles involve: (1) adding suitable Li content just above the percolation threshold to enable efficient Li diffusion without triggering irreversible oxygen redox; (2) introducing moderate F with suitable TM chemistry so that oxygen is stabilised without inducing Li-F clustering or influencing Li percolation; (3) engineering interfaces that are co-design with electrolyte and composition to suppress side reactions and irreversible oxygen loss; (4) constructing a restrained and compositionally efficient high-entropy structure to disturb SRO without impacting TM/oxygen redox; and (5) designing coherent, nanosized, well-dispersed, and reversible δ-like domains that match the overall DRX structure to form partial disordering. This 'just-enough order' strategy preserves the capacity advantage of disordered structure while leveraging the kinetics and stability of ordered structure.

To further understand the structure-performance relationship in future research, a closed-loop development workflow is recommended: (1) using simulations to build a computation-guided maps of 0-TM connectivity vs order parameter, and identify viable nucleation windows during DRXs synthesis; (2) developing in-situ/operando probes to track phase evolution and lattice breathing during the synthesis and electrochemical cycling of DRXs; (3) utilising nanoscale validation such as ED, 4D-STEM, or PDF to quantify δ-domain size, spacing and antiphase boundaries; and (4) analysing the electrochemical behaviour of DRXs to reveal the Li transport and TM/oxygen redox via GITT, EIS/DRT with gas analysis to confirm reaction kinetic and stability. These measurements can provide information on percolating-Li fraction, crystal structure evolution models, δ-domain size dispersion, and interfacial resistance growth, providing a common evaluation metric across DRXs with different compositions, entropy levels, fluorination, or processing routes. For synthesis methods, we believe the most promising path is a thermodynamically shallow and kinetically controlled process that is 'just enough' to allow nucleation but not favourable for crystal overgrowth. To achieve this condition, a combination of highly mixed precursors (such as sol–gel or carefully controlled solid-state), brief sub-eutectic anneals with well-designed cooling to seed δ-domains, and a short low-temperature defect-healing treatment to build coherence without long-range separation is recommended.

In summary, the development of DRXs should follow a clear structure-driven design principle that can control oxygen activity, limit SRO, and engineer local structure within a percolating disordered matrix. At the same time, quantitative evaluation metrics to reveal the structure-performance relationship are also important. Together with scalable and eco-efficient synthesis methods, we believe DRX cathodes can move from laboratory demonstrations to a potential commercialisation pathway towards robust, cobalt-free, high-rate, and high-energy LIB devices.

The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Shanshan Ding for the assistance in obtaining copyright permission for the figures reproduced from the referenced literature.

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Lin T, Wang Y, Dargusch M, Wang L; data collection, analysis and interpretation of results, first draft manuscript preparation: Lin T, Yuan F; manuscript revision: Lin T; Lin T and Yuan F contributed equally to this review paper. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

This review article does not report new experimental data. All data discussed in this work are available from the cited literature and publicly accessible databases referenced within the article.

-

This study is supported by Advance Queensland Industry Research Fellowships funding AQIRF064-2024RD7, and Australian Research Council Australian Laureate Fellowship (FL190100139).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Reviewed advances and challenges in cation-disordered rocksalt (DRX) cathodes for high-energy Li-ion cells.

Summarized structure, composition, lithium transport, and degradation pathways that shape DRX operation.

Clarified how structure and chemistry govern Li-transport pathways, interfacial stability, and performance.

Outlined a co-design toolkit linking composition and interfaces to safer, longer-lasting, low-hysteresis DRX.

Provided practical metrics to accelerate translation laboratory demonstrations to a potential commercialisation.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Tongen Lin, Fangfang Yuan

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article. - Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Lin T, Yuan F, Wang Y, Dargusch M, Wang L. 2025. Cation disordered rocksalt cathode materials for high-energy lithium-ion batteries. Energy & Environment Nexus 1: e012 doi: 10.48130/een-0025-0011

Cation disordered rocksalt cathode materials for high-energy lithium-ion batteries

- Received: 16 July 2025

- Revised: 25 August 2025

- Accepted: 17 September 2025

- Published online: 21 November 2025

Abstract: Cation-disordered rocksalt (DRX) materials have emerged as promising high-energy-density cathodes for next-generation lithium-ion batteries due to their compositional flexibility, high theoretical capacity, Li-excess-enabled 3D transport, and the potential to reduce or eliminate Co/Ni dependence. However, their practical applications are impeded by rapid capacity degradation, irreversible oxygen loss, and cation short-range ordering (SRO) that fragments 0-TM percolation networks. In this review, these challenges are connected to their structural origins and a co-design toolkit framed that has emerged across the literature and our analysis. The present study initially outlines how Li and d0 transition metals can synergistically balance performance and stability, then analyses oxygen-redox pathways and the origin of O loss. It is shown how SRO persists in globally disordered lattices and directly degrades Li-ion mobility and redox utilisation. Building upon these mechanisms, five effective ways to improve the performance of DRXs are evaluated: (1) balanced composition design to enable suitable Li percolation and stable anionic redox; (2) moderate, composition-specific fluorination to stabilize lattice oxygen and suppress SRO; (3) interface engineering to prevent oxygen loss; (4) introducing compositionally efficient high-entropy mixing to eliminate SRO; and (5) controlled partial ordering design to add low-barrier diffusion channels without sacrificing global disorder. Actionable guidance is also proposed for durable, high-performance DRX materials. These insights are expected to lay a foundation for the rational design of next-generation DRX cathodes, supporting their future commercialisation in sustainable energy storage technologies.