-

Over the past two decades, outbreaks of global infectious diseases such as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)[1], H1N1 influenza[2], Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS)[3], and Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)[4], have caused significant economic and public health losses. These highly contagious pathogens spread through airborne micro-aerosol particles, raising concerns among global and national health organizations. Indoor microbial aerosols— comprising small biological particles such as bacteria, fungi, and viruses[5] —pose health risks, including infectious diseases, toxicity, allergies, and respiratory issues[6−8]. Collectively, understanding the distribution and behavior of indoor microbial aerosols is essential for effective disease prevention and safeguarding public health.

Air samplers are critical tools for collecting biological aerosols and providing foundational data for research and intervention. Researchers have developed a variety of microbial aerosol samplers based on different operational principles, including liquid impingers, impactors, filter-based samplers, cyclones, and centrifugal samplers[9]. In earlier research, Klaus Willeke et al.[10] proposed an aerosol collection method combining surface impaction with liquid collection. In this method, particles are injected into a rotating airflow and subsequently removed onto a collection surface. This enables efficient collection of minute particles, circumvents issues related to liquid evaporation, and reduces reaerosolization and particle bounce. Most studies primarily utilize a single sampling device, with relatively few investigations comparing the performance of multiple devices. For instance, Puthussery et al.[11] employed a wet-wall cyclone sampler, a liquid impinger, and a water-based condensation sampler to collect samples containing inactivated SARS-CoV-2 strains at different concentrations within an aerosol chamber, though this study excludes the commonly used membrane filtration samplers. Similarly, Abeykoon et al.[12] aerosolized Coxiella burnetii (0.2–0.4 μm) in an indoor environment and used three types of air samplers (membrane filtration, liquid impinger, and wet-wall cyclone) to measure its concentration. While this study primarily focused on the bacterial sampling efficiency of samplers, the sampling efficiency for viruses remains inadequately explored.

Beyond the choice of sampler, studies have revealed that both the sampling medium and the sampling flow rate significantly influence collection performance[12,13]. Abeykoon et al.[12] evaluated two liquid sampling media (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] and alkaline polyethylene glycol [Alk PEG]) and found that PBS exhibited a higher recovery efficiency. Chang et al.[13] assessed the sampling efficiency of two aerosol samplers— a liquid impinger and a cyclone sampler—for indoor fungal aerosols using PBS as the collection liquid. Despite these findings, comprehensive research on the performance of other commonly used liquid sampling media for bacterial and viral aerosols remains limited.

Microorganisms collected by the microbial sampler often require cultivation or amplification using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), which significantly prolongs the detection process and limits the feasibility of real-time evaluation. Additionally, inherent limitations of samplers in capturing all airborne microbial aerosols, coupled with variations in microorganism survival rates during cultivation or detection, can affect the accuracy of sampling efficiency assessments. In contrast, fluorescence-based technology eliminates the need for microbial cultivation or amplification, substantially reducing the detection time.

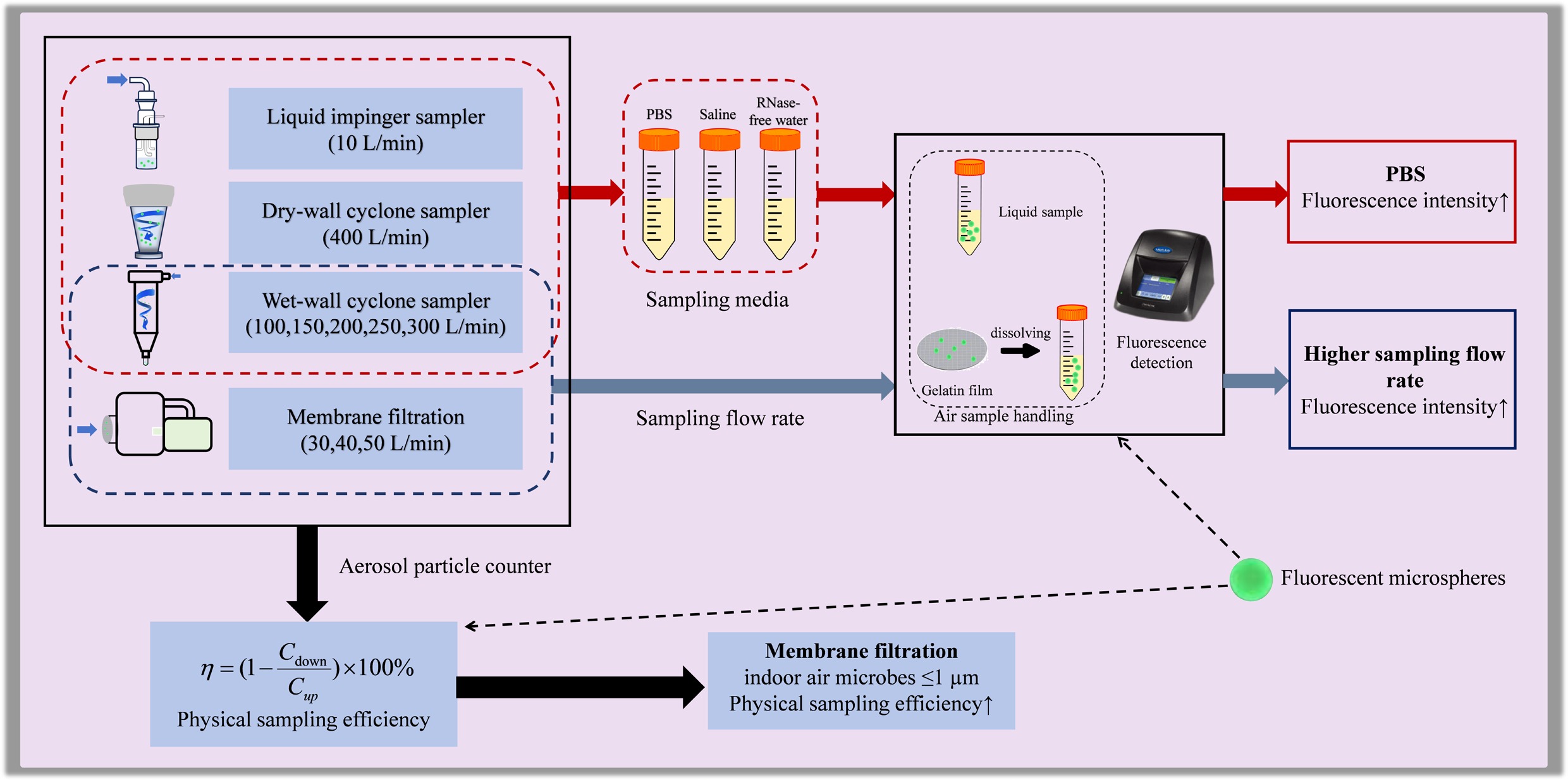

This study employed fluorescence technology to compare the sampling efficiency of four widely used air samplers, each based on distinct operational principles, for airborne microorganisms under varying sampling media. The efficiency of these samplers in capturing particles of different sizes, including bacteria and viruses, was also investigated. By estimating the capture efficiency of air samplers for airborne pathogens in indoor environments, the findings aim to provide technical references for future field sampling and research on airborne microorganisms.

-

This study conducts a simulated sampling analysis of bacteria and viruses associated with respiratory diseases. Common respiratory pathogens, such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, and Streptococcus haemolyticus, typically exhibit particle sizes of approximately 1 μm. For instance, Staphylococcus aureus, a prevalent opportunistic pathogen, has a cell diameter of approximately 1 μm[14]. Gu et al. reported that viruses associated with particles 100–200 nm in size have lower viability than those carried on particles 300–450 nm in size[15]. Notably, particles within the size range of 0.3–1 μm have extended suspension times and greater propagation distances in the air. These particles are easily transported by airflow and may penetrate deeply into the lungs through the respiratory tract. Due to their small size and aerodynamic properties, particles in this range are challenging to capture effectively with traditional sampling methods. While conventional samplers are often optimized for larger particles, specialized techniques and equipment are required to collect smaller particles efficiently.

To address this challenge, fluorescent polystyrene microspheres (modified with -COOH groups) with particle sizes of 300 nm, 500 nm, and 1 μm (Zhongke Leiming, Beijing, China) were selected to simulate airborne bacterial and viral particles. These microspheres were chosen because their particle size range closely corresponds to that of many respiratory viruses and bacteria. Bacteria and viruses typically carry negative charges on their surfaces. The negative charges on viral surfaces may arise from modifications to capsid proteins or envelope glycoproteins[16]. Carboxyl groups (-COOH) can dissociate hydrogen ions (H+) in aqueous solutions, thereby imparting a negative charge to the surface of microspheres. In addition, polystyrene itself is a hydrophobic material, and the surfaces of bacteria and viruses also exhibit some hydrophobicity[17,18]. Therefore, polystyrene microspheres modified with -COOH groups serve as effective proxies for bioaerosols of comparable sizes. The use of fluorescent microspheres offers several advantages, including ease of detection, high stability, and no interference with biological activity, making them ideal for experimental purposes.

The polystyrene fluorescent microspheres have a 1% solid content (w/v) at 10 mg/mL, corresponding to a fluorescent particle concentration of 1.8 × 1010 particles/mL. These microspheres have an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and an emission wavelength of 525 nm. For experimentation, the original polystyrene fluorescent microsphere solution was diluted 1,000-fold to achieve a final suspension concentration of 1 × 10−2 mg/mL, corresponding to a fluorescent particle concentration of 1.8 × 107 particles/mL. To ensure measurement precision, the standard deviation of the fluorescence signal intensity for the 1,000-fold diluted microsphere suspension, as detected with the GloMax Multi Jr fluorescence detector (Promega, USA), was maintained below 10%. The prepared suspension was aliquoted, protected from light, and stored at 2–8 °C to maintain stability for subsequent use.

Aerosols generation system and sampling apparatus

-

The human respiratory tract inherently functions as an aerosol generator. During breathing—especially when coughing, sneezing, or speaking—the liquid in the respiratory tract is atomized into minute droplets, forming an aerosol[19]. The generation of such aerosols resembles the operating principles of certain aerosol generators, such as nebulizers or sprayers, which disperse liquids into tiny particles through mechanical force or airflow[20].

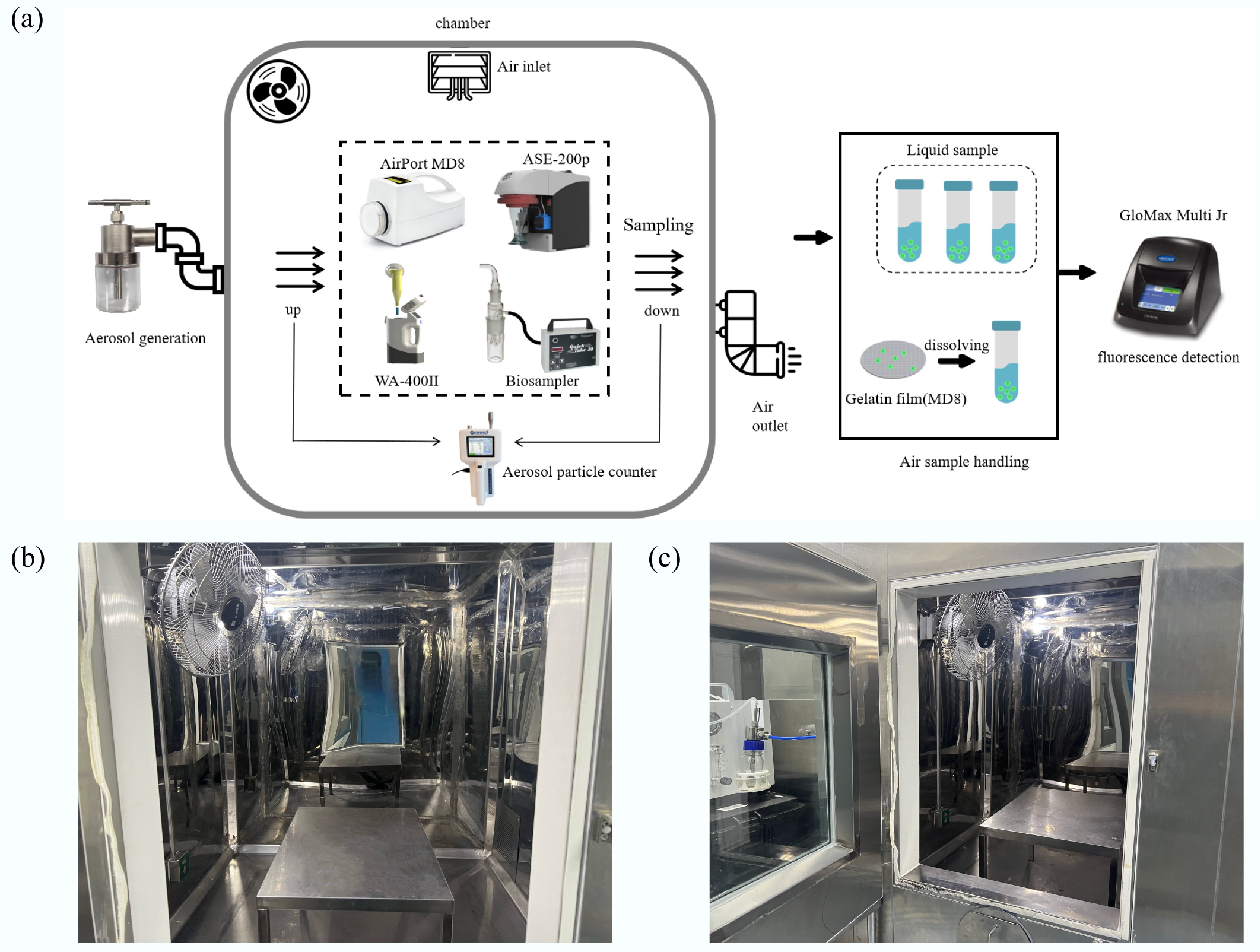

The aerosol generation device employed the NSF-6A liquid aerosol generator (Tawang Technology, Shanghai, China), which operates on the principle of collision, as shown in Fig. 1a. The device applies the Bernoulli principle, causing the liquid suspension to strike the interior of the tank and generate small-sized aerosols[21]. This device is equipped with an integrated miniature air compressor and an external oil-water separator. To ensure the use of dry gas for aerosolization, air is first passed through the oil-water separator before reaching the nozzle of the sample bottle. The aerosol spray rate was controlled by adjusting the flowmeter and pressure relief valve, with real-time monitoring via a pressure gauge. For the generation process, 20 mL of prepared fluorescent microsphere suspension was introduced into the sample bottle of the aerosol generator. The aerosol concentration was maintained at 20 L/min, with the air source pressure ranging from 0.1 to 0.5 MPa. Atomization of the liquid was performed for 10 min.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study and structural configuration of the environmental chamber. (a) Operational workflow for the experimental chamber and following fluorescence detection. (b) Internal structural layout of the environmental chamber. (c) Connection schematic linking the environmental chamber to the aerosol generator.

As shown in Fig. 1b, c, a 3 m3 environmental chamber constructed from stainless steel plates and tempered glass was used as the test environment. Gaps between the steel plates were sealed with polyurethane foam to ensure airtightness. The fresh air system's supply vent was located on the left side of the chamber's ceiling, while the exhaust vent was positioned on the lower-right chamber wall. A fan at the top of the chamber circulated air for 1 min after atomization to achieve a uniform aerosol distribution. The atomizer nozzle was connected to the environmental chamber via a rubber tube, forming the aerosol generation chamber. Exhaust during testing was managed through both individual sampler collection systems and the mechanical exhaust from the fresh air system.

Prior to each aerosol generation experiment, the chamber's internal temperature and humidity were adjusted to 25 ± 5 °C and 50 ± 5%, respectively. To prevent uncontrolled aerosol dispersion outside the chamber, the internal fresh air system and temperature-humidity control system were turned off before aerosolization. Additionally, to address residual clean air in the chamber's pipes after fan operation, measures were taken to prevent its escape into the testing chamber during sampling, thereby maintaining consistent indoor and outdoor air pressure.

After every experimental run, the chamber was flushed with high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA)-filtered air at a flow rate of 300 L/min for at least 10 min to remove any remaining fluorescent microspheres. The chamber background was then monitored by collecting blank samples under identical conditions. The background level of air fluorescence microspheres in the chamber was maintained at 2.34–19.87 FSU, with an average of 10.40 FSU. The fluorescence standard unit (FSU) values obtained from these pre-sampling chamber flushes were consistently less than 10% of the corresponding sample fluorescence values, confirming minimal carryover.

If initial removal attempts were unsuccessful, the ventilation system of the environmental chamber was activated, and the volume of fresh air intake increased to enhance internal air circulation. Continuous ventilation was maintained for 2–3 h to purge fluorescent microsphere-containing air from the chamber. Following ventilation, chamber humidity was adjusted to 80% to promote hygroscopic moisture absorption by microspheres, increasing their mass and accelerating sedimentation to the chamber floor. Finally, the chamber bottom was gently cleaned using soft, lint-free wipes moistened with deionized water to remove any remaining microspheres.

Microbial aerosol samplers

-

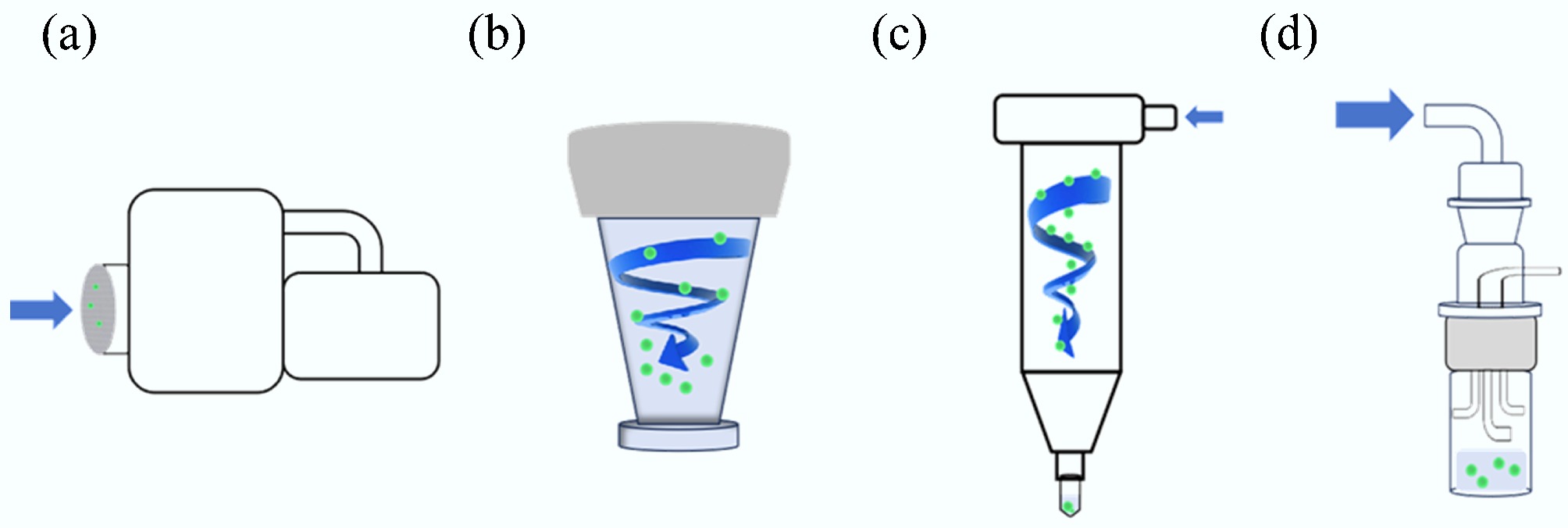

Different aerosol collection methods employ distinct physical principles to separate aerosol particles from the air. Similarly, the human respiratory system can collect aerosol particles. Inhaled aerosol particles can deposit in various regions of the respiratory tract through mechanisms such as inertial impaction, diffusion, and gravitational sedimentation[22].

This study evaluated the performance of four microbial aerosol samplers: the liquid impinger sampler (Biosampler, SKC, USA), the membrane filtration sampler (AirPort MD8, Sartorius, Germany), the dry-wall cyclone sampler (WA-400II, Dinglan Technology, Beijing, China), and the wet-wall cyclone sampler (ASE-200p, Langsi Medical Technology, Shenzhen, China). The liquid impinger sampler, known for its distinctive functionality and efficacy in capturing bioaerosols containing RNA viruses such as SARS-CoV-2[23], was included in the evaluation. The membrane filtration sampler was selected for its ease of use and widespread application in microbial aerosol research[24,25].

Given challenges associated with long-duration sampling, including potential biological degradation, short-duration sampling of large air volumes has gained prominence in field research[26−28]. Hence, the dry-wall cyclone sampler (WA-400II) and the wet-wall cyclone sampler (ASE-200p) were chosen for evaluation. These high-flow cyclone aerosol samplers use fans to generate high-speed cyclones that centrifuge biological particles into a liquid medium. The wet-wall cyclone sampler is well-suited for qualitative studies of low-concentration bioaerosols, such as coronaviruses, in potentially contaminated environments[29].

To investigate the impact of sampling media and sampling flow rates on the sampling efficiency of liquid aerosol samplers, three liquid sampling media were selected: RNase-free water (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), and Langsi collection fluid (irradiated physiological saline, Langsi Medical Technology, Shenzhen, China).

Twenty milliliters of each sampling medium were added separately to the liquid impinger sampler's sampling bottle. The sampler was connected to the QuickTake-30 air sampling (SKC, USA) using silicone tubing. The aspirator pump operated at a fixed sampling flow rate of 10 L/min, causing the air to rotate as it was drawn into the collection bottle. Aerosols were subsequently separated under centrifugal force and impacted the inner wall of the bottle. Due to rotational motion, aerosol particles adhering to the inner wall were efficiently washed into the liquid medium[30].

For the wet-wall cyclone sampler, 15 mL of each sampling liquid was placed in Langsi polyethylene sampling cups and loaded onto the device. The wet-wall cyclone sampler, at five different sampling flow rates (100, 150, 200, 250, and 300 L/min), used the inertia generated by the high-speed rotation of airflow in the cylindrical or conical section of the cyclone to separate bioaerosol particles from the airflow. The particles were collected by the sampling medium via the continuous wash along the inner wall of the cyclone[31].

A sampling tube containing 3 mL of collection liquid was connected to the lower end of the dry-wall cyclone sampler's sampling cylinder, ensuring a tight seal between the fan and the sampling cylinder. The dry-wall cyclone sampler uses a negative-pressure design with a fan for air extraction. At a fixed flow rate (400 L/min), the cyclone's centrifugal force directs the airflow to form a centrifugal vortex within the sampling cylinder, concentrating particles at the bottom to achieve solid-gas separation. The concentrated air sample, using a centrifugal sampling principle, was forced to impact the sampling liquid within the tube[32].

The membrane filtration sampler was equipped with a 3 μm pore-size gelatin membrane (Sartorius, Germany) supported by a stainless-steel mesh holder to prevent deformation during high-flow sampling. The system was operated in constant-flow mode at 30–50 L min−1, and the pressure differential across the membrane was continuously monitored to ensure stable operation. The air was drawn in through the porous sampling head, impacting the gelatin membrane. The aerosol particles in the air were captured on the surface of the membrane[33].

After each sampling run, the gelatin membranes were visually inspected for rupture, detachment, or surface irregularities; no physical damage was observed across all experiments. The effective sampling area of the membrane was 4.9 cm2, as specified by the manufacturer. To verify membrane integrity, condensate collected from the downstream exhaust line was periodically analyzed by fluorescence spectrophotometry, and no detectable fluorescence was observed, confirming that no particle breakthrough occurred. Although the nominal pore size of the gelatin membrane (3 μm) exceeds the diameter of the 0.3 μm fluorescent microspheres, fine particles were effectively captured through Brownian diffusion, inertial impaction, and interception. The viscoelastic and hygroscopic characteristics of hydrated gelatin contribute significantly to improved particle adhesion and reduced bounce rates. This optimization facilitates the efficient collection of submicron aerosols, as has been documented in prior research[34−36].

The distance between the aerosol generator's emission nozzle and the inlet of each sampler was maintained at 0.5–1 m during aerosol sampling. In this experiment, the four instruments were set to sample under a predetermined gas volume of 2,000 L, with the sampling parameters as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Sampling conditions for four samplers with a sampling volume of 2 m3

Sampler type Flow (L/min) Time (min) Medium Membrane filtration 30, 40, 50 66, 50, 40 Sartorius gelatin membrane Liquid impinger 10 200 RNase-free water Wet-wall cyclone 100, 150, 200, 250, 300 20, 13.3, 10, 8, 6.7 Irradiated physiological saline Dry-wall cyclone 400 5 PBS Additionally, to avoid bias in testing the performance of the air samplers in a specific order, each sampler type was tested randomly and repeatedly, with three tests per sampler for each experiment. Before sample detection, a gradient-diluted standard concentration of fluorescent suspension was used to calibrate the fluorescence detector.

Air sample processing and statistical analysis

-

After air sampling with the membrane filtration sampler, the filter membrane was immersed in 30 mL of 0.01M PBS and stirred at room temperature for 10 min until the gelatin membrane was completely dissolved. The fluorescence intensity of the liquid samples collected from the four samplers was then measured using the GloMax Multi Jr. Fluorescence standard units (FSU) were used to report the results. In addition, fluorescence was measured promptly after sampling to avoid signal attenuation, and no significant decline in fluorescence intensity was observed during the experiments.

Data analysis was performed using SPSS 26.0 (IBM Software). The fluorescence intensity results for 0.3 and 1 μm fluorescent microspheres collected by different samplers were statistically analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) to evaluate differences across three or more data sets. All pairwise comparisons were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni method. Differences were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

Evaluation of the sampling efficiency for microspheres of different particle sizes

-

In this experiment, monodisperse polystyrene fluorescent microspheres with particle sizes of 0.3, 0.5, and 1 µm were selected. The fluorescent microspheres were suspended in PBS, then introduced into the NSF-6A aerosol generator. Fluorescent microsphere aerosols of individual particle sizes were generated in the simulated chamber at a flow rate of 20 L/min. To ensure uniform dispersion of the microspheres, the fan above the chamber was activated, producing a homogeneous aerosol. Once the aerosols were stably dispersed, four samplers with different sampling flow rates were used to collect aerosols within the simulated chamber. Aerosol concentration upstream (Cup) and downstream (Cdown) of the sampler were measured using the PC3016 particle counter (Graywolf, USA) at a flow rate of 2.83 L/min for 1 min each. This process was repeated three times, and the standard deviation was calculated to ensure it remained below 10%. If the standard deviation was above 10%, the measurement was repeated. Sampling efficiency for different particle sizes was calculated using the Eq. (1)[37] to determine the physical sampling efficiency (η).

$ \eta =\left(1-\dfrac{{{C}}_{\text{down}}}{{{C}}_{\text{up}}}\right)\times 100{\text{%}} $ (1) -

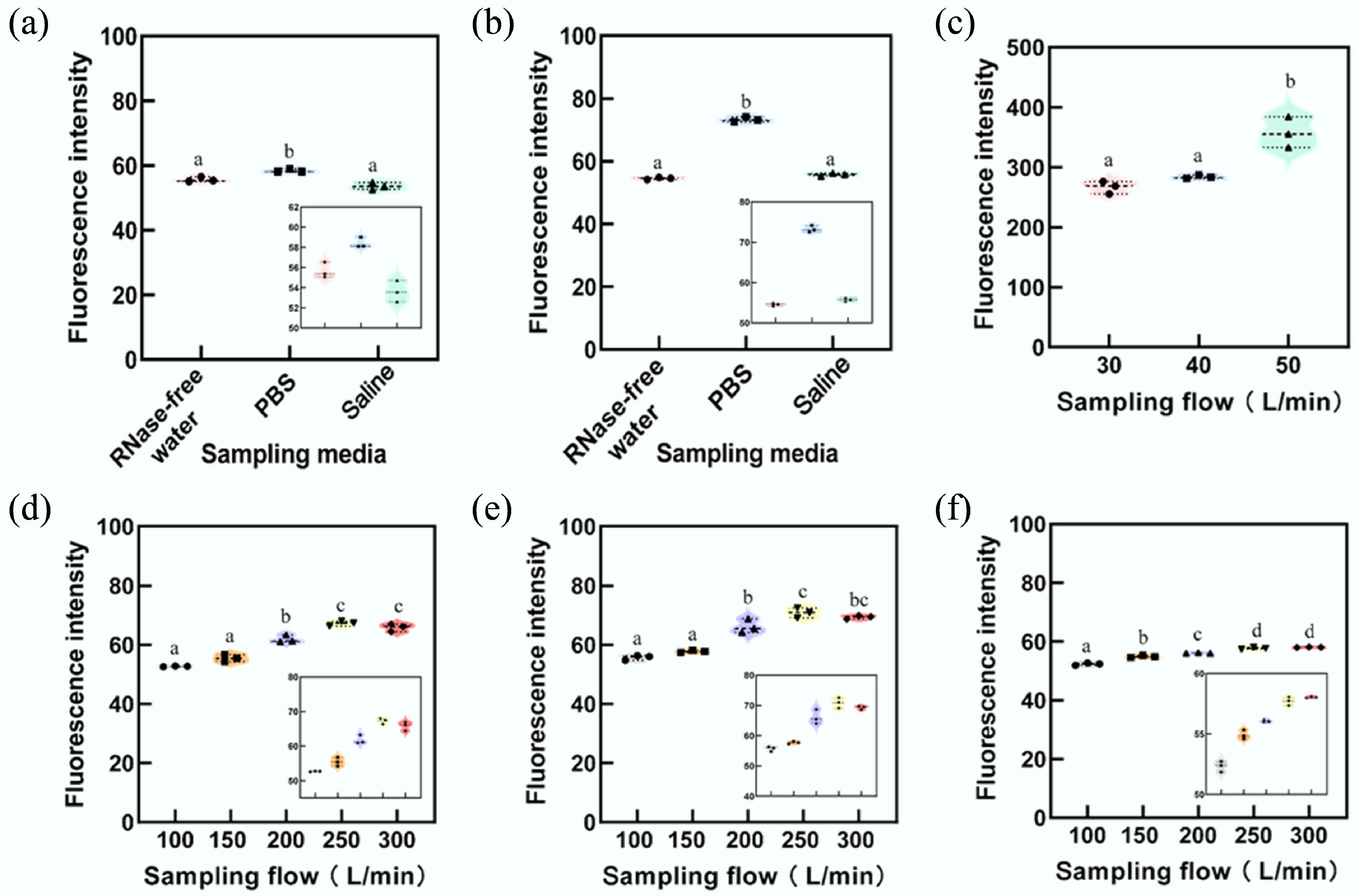

The fluorescence intensity of 0.3 and 1 μm polystyrene fluorescent microspheres used as simplified surrogates to represent the lower bound of particle sizes associated with virus- and bacteria-bearing aerosols is illustrated in Figs 2 and 3 for each sampler. The results indicate that the membrane filtration sampler demonstrates a sampling efficiency that is four to six times greater for 0.3 µm microspheres and five to ten times greater for 1 µm microspheres compared to the liquid impinger sampler, the dry-wall cyclone sampler, and the wet-wall cyclone sampler (Figs 2 and 3). Furthermore, the fluorescence intensity of samples collected by the membrane filtration sampler is significantly higher than that obtained with the other three samplers (Figs 3 and 4).

Figure 2.

Particle capture mechanisms for four samplers. (a) Airport MD8. (b) ASE-200p. (c) WA-400II. (d) Biosampler.

Figure 3.

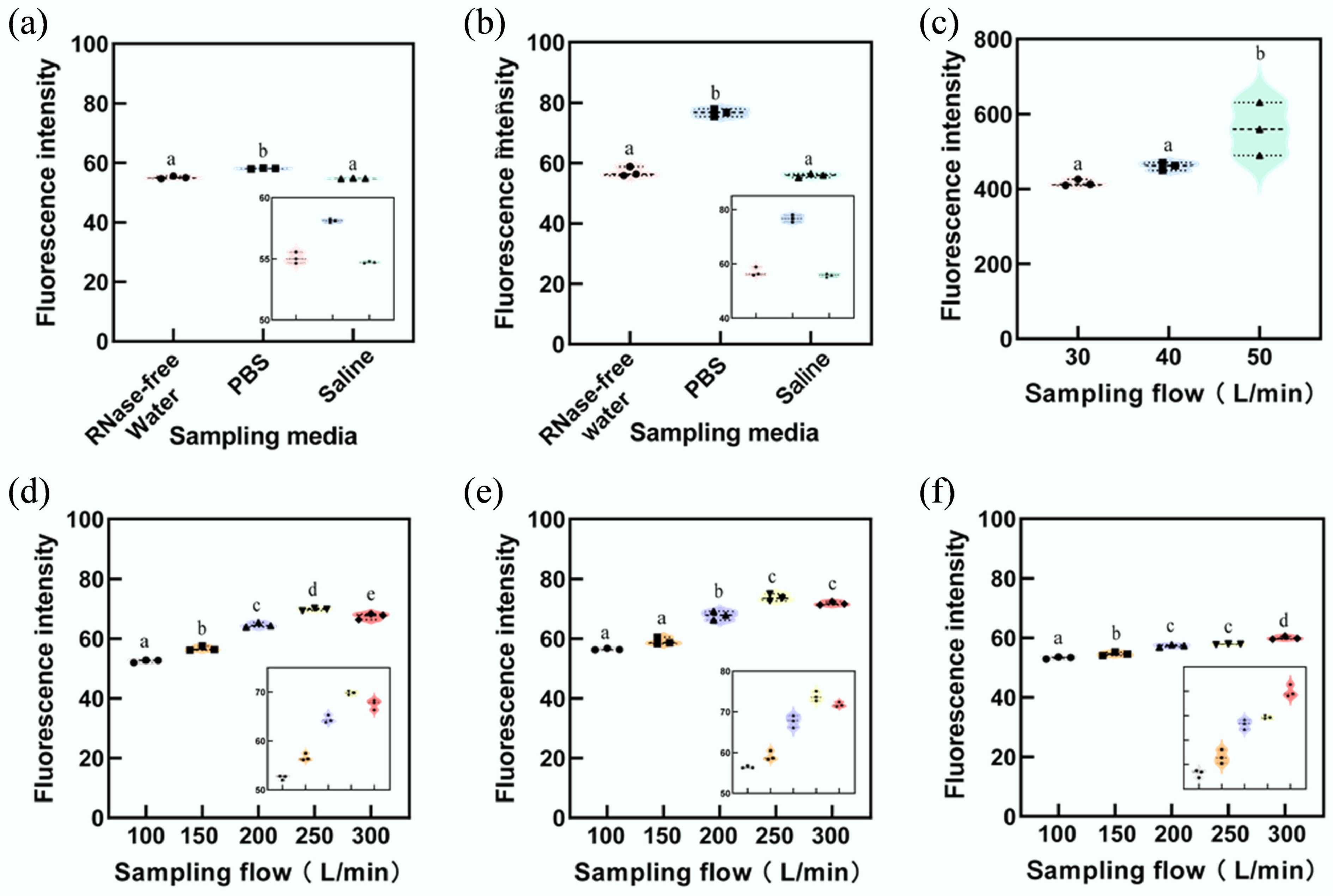

Fluorescence intensity of sampled microspheres with a diameter of 0.3 μm. The membrane filtration sampler demonstrated superior performance in collecting 0.3 μm particles compared to other samplers. Among the liquid sampling media tested, PBS showed the highest efficiency. To enhance clarity and emphasize the differences in results, specific stacked plots have been enlarged. Subfigures illustrate results for: (a) Liquid impinger sampler. (b) Dry-wall cyclone sampler. (c) Membrane filtration sampler. (d) Wet-wall cyclone sampler using RNase-free water. (e) Wet-wall cyclone sampler using PBS. (f) Wet-wall cyclone sampler using irradiated physiological saline. Statistically significant differences are denoted by lowercase letters (a, b, c, and d), where the same letter indicates no statistical difference, and different letters represent statistically significant differences (ANOVA, p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Fluorescence intensity of sampled microspheres with a diameter of 1 μm. The membrane filtration sampler exhibited the highest performance in collecting 1 μm particles. Among liquid sampling media, PBS proved to be the most effective. For clarity, some stacked plots have been enlarged to emphasize differences in results. (a) Liquid impinger sampler. (b) Dry-wall cyclone sampler. (c) Membrane filtration sampler. (d) Wet-wall cyclone sampler with RNase-free water. (e) Wet-wall cyclone sampler with PBS. (f) Wet-wall cyclone sampler with irradiated physiological saline. Lowercase letters (a, b, c, d, and e) indicate statistically significant differences. Identical letters represent no statistical significance, while different letters denote statistically significant differences (ANOVA, p < 0.05).

Influence of sampling medium on sampler collection effectiveness

-

Figures 3a and 4a indicate that, when PBS was used as the sampling medium, the fluorescence intensity of collected samples was higher than that of samples collected using RNase-free water or irradiated physiological saline (Supplementary Table S1). Although samples collected with RNase-free water showed higher fluorescence intensity than those collected with irradiated physiological saline, the difference was not statistically significant.

In the experiment involving virus substitutes (0.3 μm microspheres), the liquid impinger sampler using PBS exhibited a fluorescence intensity approximately 4.94% higher than that of RNase-free water and 8.91% higher than irradiated physiological saline (F = 25.86, p = 0.001). For the dry-wall cyclone sampler, the fluorescence intensity of samples collected with PBS was 34.38% and 31.34% higher than RNase-free water and irradiated physiological saline, respectively (F = 1,015, p < 0.001).

For the wet-wall cyclone sampler, across five flow rates (100, 150, 200, 250, and 300 L/min), the fluorescence intensity of samples collected using PBS exceeded that of RNase-free water by 5.69%, 4.04%, 6.95%, 5.38%, and 5.32%, respectively. Similarly, compared with irradiated physiological saline, samples collected using PBS showed fluorescence intensities that were 6.44%, 5.04%, 17.96%, 22.71%, and 19.42% higher, respectively, under the same flow conditions.

In the collection of bacterial substitutes (1 μm microspheres), the liquid impinger sampler with PBS as the medium exhibited fluorescence intensities 5.54% and 6.19% higher than RNase-free water and irradiated physiological saline, respectively (F = 131.9, p < 0.001). For the dry-wall cyclone sampler, the corresponding increases were 34.56% and 37.31% higher for PBS compared to RNase-free water and irradiated physiological saline, respectively (F = 265.7, p < 0.001).

The wet-wall cyclone sample demonstrated similar trends. Across five flow rates (100, 150, 200, 250, and 300 L/min), PBS yielded fluorescence intensities higher than RNase-free water by 7.48%, 4.43%, 4.96%, 5.68%, and 6.33%, respectively. Against irradiated physiological saline, the intensities were higher by 5.93%, 8.29%, 18.17%, 27.43%, and 19.66%, respectively.

Influence of sampling flow rate on sampler collection effectiveness

-

In experiments examining virus substitutes (0.3 μm microspheres) and bacterial substitutes (1 μm microspheres), the membrane filtration sampler's fluorescence intensity increased with higher flow rates. Figures 3c and 4c demonstrate that, at a sampling flow rate of 50 L/min, the fluorescence intensity of virus substitutes surpassed results obtained at 30 L/min and 40 L/min by 33.97% and 25.92%, respectively (F = 26.557, p < 0.01). Similarly, for bacterial substitutes, the intensities were 34.65% and 21.46% higher at 50 L/min compared to 30 L/min and 40 L/min, respectively (F = 9.388, p < 0.05) (Supplementary Table S2).

The wet-wall cyclone sampler also showed an overall increase in fluorescence intensity of collected virus and bacterial substitutes as flow rates rose from 100 to 250 L/min. However, at 300 L/min, fluorescence intensity for virus substitute samples collected with PBS and RNase-free water decreases by 1.48 FSU and 1.37 FSU, respectively, compared to the results collected at 250 L/min. Similarly, bacterial substitute fluorescence intensities decreased by 1.94 FSU and 2.27 FSU, respectively, when comparing 300 to 250 L/min flow rates (Supplementary Table S3).

Physical sampling efficiency of four samplers

-

The sampling efficiency of the four samplers was influenced by factors such as particle size, inertial impaction, and interactions with water molecules in the air. This study analyzed the efficiency of each sampler in collecting microspheres of varying particle sizes.

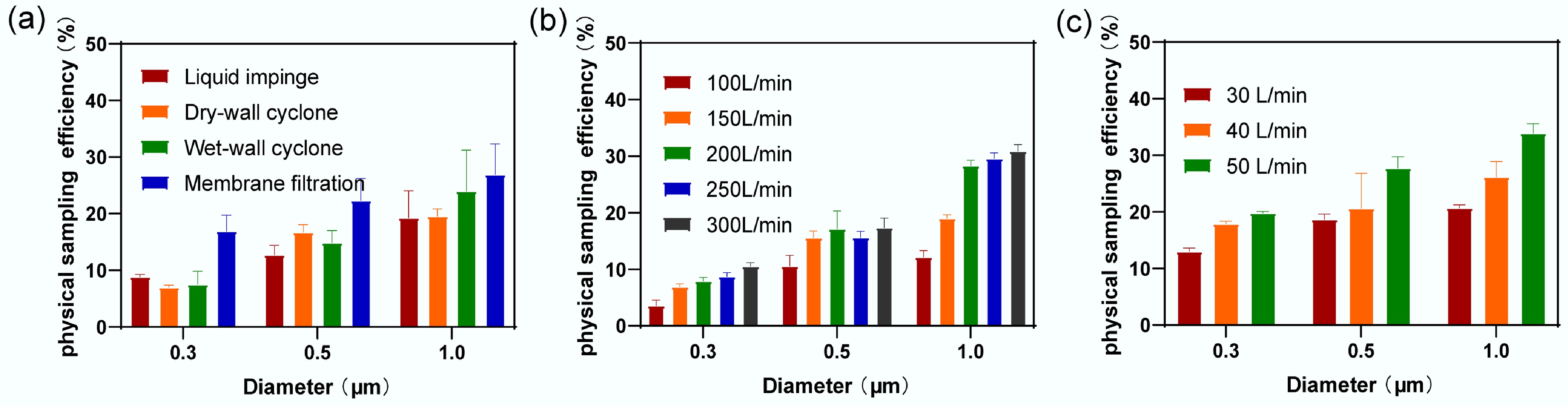

For the liquid impinger sampler, the sampling efficiency increased from (8.83 ± 0.58)% for 0.3 µm particles to (19.25 ± 5.91)% for 1 µm particles. Similarly, the dry-wall cyclone sampler exhibited an increase in sampling efficiency from (6.98 ± 0.47)% at 0.3 µm to (19.56 ± 1.57)% at 1 µm. As shown in Fig. 4, the sampling efficiency improved with increasing particle size. This trend was particularly pronounced for the dry-wall cyclone sampler, which showed a significant efficiency gain at 0.5 µm (Fig. 5a).

Figure 5.

Sampling efficiency of different principal samplers for three particle sizes of microspheres. (a) Sampling efficiency of four types of samplers. (b) Sampling efficiency of wet-wall cyclone sampler at five different flow rates. (c) Sampling efficiency of membrane filtration sampler at three different flow rates.

The liquid impinger sampler and the dry-wall cyclone sampler did not achieve a maximum sampling efficiency of 50% in this experiment, making it impossible to calculate their Da50 values. Da50 refers to the aerodynamic diameter of particles under specific sampling conditions at which the sampling efficiency reaches 50%. It represents the particle size at which half of the particles are collected while the other half remains uncollected. This parameter is essential for evaluating sampler performance, optimizing sampling processes, and understanding the distribution and behavior of atmospheric particles.

The wet-wall cyclone sampler's sampling efficiency at five flow rates is presented in Fig. 5b. For aerosol particles with a diameter of 0.3 µm, the sampling efficiencies at flow rates of 100, 150, 200, 250, and 300 L/min were (3.59 ± 1.22)%, (6.90 ± 0.61)%, (7.91 ± 0.82)%, (8.72 ± 0.86)%, and (10.53 ± 0.81) %, respectively. For particles with a diameter of 1 µm, the corresponding sampling efficiencies increased to (12.14 ± 1.43)%, (19.01 ± 0.79)%, (28.31 ± 1.17)%, (29.59 ± 1.20)%, and (30.90 ± 1.42)%, respectively. Despite these increases, the maximum sampling efficiency at the highest flow rate for particles of various sizes remained below 50%, preventing the calculation of Da50.

The sampling efficiency of the membrane filtration sampler at three flow rates (30, 40, 50 L/min) is shown in Fig. 5c. For aerosol particles with a diameter of 0.3 µm, the sampling efficiencies were (13.00 ± 0.72)%, (17.87 ± 0.60)%, and (19.80 ± 0.27)%, respectively. For particles with a diameter of 1 µm, the sampling efficiencies increased to (20.70 ± 0.90)%, (26.16 ± 3.35)%, and (33.91 ± 2.05)%, respectively. Similar to the wet-wall cyclone sampler, the membrane filtration sampler's sampling efficiency did not exceed 50% at the tested flow rates, thus precluding Da50 calculations.

-

The membrane filtration sampler demonstrates superior performance compared to liquid impinger and cyclone samplers for collecting indoor microbial air samples. It enhances both the efficiency and reliability of sampling while preventing material loss, making it particularly promising for indoor air collection experiments. Commonly used media for microbial collection in the literature include DMEM and PBS for liquid samplers, as well as gelatin membranes and PTFE for filtration-based samplers[33,38]. This study conducted a comparative analysis between liquid and membrane filtration samplers, revealing that under high concentrations of virus substitutes (0.3 μm) and bacterial substitutes (1 μm), the membrane filtration sampler exhibits superior collection capabilities. This finding aligns with the results of Abeykoon et al., who also observed that, under high-concentration bacterial aerosol conditions, membrane filtration samplers outperform liquid impaction samplers and wet-wall cyclone samplers, with higher recovery rates[12].

Abeykoon et al.[12] employed Coxiella burnetii, a biological agent with a size range of 0.2–0.4 μm, whereas this research utilized synthetic fluorescent microspheres. C. burnetii possesses distinct surface charge and biochemical properties that can influence its interactions with sampling media such as filters. Biological particles often exhibit electrostatic or hydrophobic affinities that differ from those of inert particles, potentially enhancing their adherence to filter surfaces. In contrast, microspheres are highly uniform in size and morphology, and their surface chemistry can be precisely controlled during manufacturing, allowing for a standardized assessment of the physical collection efficiency of sampling devices.

In this study, the membrane filtration efficiency for 0.3 μm microspheres was approximately 19.8%, markedly lower than the 90% bacterial recovery rate reported by Abeykoon et al.[12]. Several factors may account for this discrepancy. First, differences in filter materials, including pore size distribution, surface roughness, and chemical composition, can influence particle retention, even when nominal pore sizes are similar. More tortuous or irregular pore structures may hinder particle passage and reduce apparent efficiency. Second, variations in sampling conditions, such as airflow rate and relative humidity, can affect particle behavior. Elevated flow rates may increase particle bypass, while humidity fluctuations can alter particle size and electrostatic charge. Finally, differences in particle generation and delivery methods between studies could result in distinct initial concentrations or spatial distributions, further contributing to the observed efficiency variation.

Filters are commonly used for air sampling because they are simple and easy to use. However, during sampling and extraction, filter dehydration can significantly affect the bio-recovery rate. Additionally, filters can capture particles smaller than the nominal pore size through other capture mechanisms, such as diffusion and interception, which work alongside filtration[39]. Burton et al. observed that the capture efficiency of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) and gelatin filters for virus-like particles exceeded 93%[40]. In contrast, polycarbonate filters had lower capture efficiencies, ranging from 22% to 49%, though these values were still higher than the efficiency of impactors. While gelatin filters are highly effective, they allow for unrestricted sampling duration or flow rate. However, using filter membranes to study virus bioaerosols can potentially cause structural damage to virus particles, affecting their bioactivity[34]. For this reason, some researchers prefer to use gelatin filters, as they have minimal impact on infectivity. However, samples can only be collected at low flow rates for about 30 min[41].

Puthussery et al.[11] excluded membrane filtration samplers from their study, likely for several practical reasons. One primary concern is the potential for filter clogging, particularly in environments with high particle loads. Clogging can reduce airflow, lower sampling efficiency, and compromise measurement accuracy. Another limitation is the labor-intensive nature of filter handling and post-sampling analysis, as filters must be carefully removed, transported, and processed, increasing time requirements and the risk of handling errors.

However, the findings of the present study support the inclusion of membrane filtration samplers in future SARS-CoV-2 monitoring efforts. Although their efficiency for 0.3 μm microspheres was lower than some reported biological recovery rates, membrane filtration samplers effectively captured submicron particles and are well-suited for collecting larger, virus-containing droplets. These samplers are simple to operate, adaptable to both indoor and outdoor environments, and practical for large-scale surveillance. The study provides a performance baseline, and future work should focus on optimizing filter materials, refining sampling conditions, and improving post-sampling processing through enhanced filter design and automated analytical systems.

In practical aerosol sampling applications, the choice of sampling principle depends on various factors, including particle size, concentration, shape, and sampling environment[11,12,38,42−44]. Notably, different principles exhibit varying degrees of adaptability to these particle characteristics, resulting in differences in sampling efficiency. Therefore, when selecting an aerosol sampler, it is essential to consider the particle complexity in the target environment to ensure accurate and effective sampling.

Furthermore, aerosol samplers based on different principles can differ significantly in terms of cost and complexity, both in manufacturing and maintenance[12,45]. These differences influence the practicality and feasibility of the equipment for real-world applications. When choosing an appropriate aerosol sampler, it is crucial to assess not only its sampling performance but also the economic implications of manufacturing and maintenance. A comprehensive evaluation ensures the long-term stability and sustainability of the equipment.

Lastly, the choice of aerosol samplers is influenced by the target parameters of the study[45,46]. Different principles may prioritize different target parameters. For instance, some may emphasize sampling efficiency, while others focus on preserving particle characteristics[47,48]. Therefore, clearly defining the target parameters is essential for selecting the most appropriate aerosol sampler to meet the specific needs of research or monitoring.

Collectively, selecting an aerosol sampler requires a comprehensive assessment of application needs, environmental conditions, and target parameters. By thoroughly understanding the advantages and disadvantages of different principles, researchers can choose the most suitable sampler for their specific application, enhancing the reliability and comparability of the collected data.

Impact of sampling media on the sampling efficiency of samplers

-

In this study, a significant difference was observed between bacterial substitutes collected with PBS as the sampling liquid and those collected with RNase-free water or irradiated physiological saline. Interestingly, while the sampling liquid influenced both particle sizes, the enhancing effect of PBS on the collection of bacterial substitutes was more pronounced. For virus substitutes, however, the difference in sample fluorescence intensity between samples collected with PBS and those collected with RNase-free water or irradiated physiological saline was relatively small. These findings suggest that the larger size and slower settling velocity of bacterial substitutes may contribute to their enhanced capture by the air sampler.

In indoor microbial aerosol experiments using fluorescent microspheres, PBS was found to be the most effective sampling medium. Polystyrene fluorescent microspheres, commonly used as markers in air microbial aerosol sampling, were employed in this study[30]. Both PBS and physiological saline can serve as carriers for these microspheres, and RNase-free water can also serve as a sampling medium. The results indicate that PBS offers superior collection efficiency. This can be attributed to its ability to maintain solution pH stability and enhance the ionic conductivity of the electrolyte[31]. Fluorescent microspheres are highly sensitive to pH changes, and fluctuations can affect their structure and performance. PBS helps stabilize and preserve the fluorescence properties of polystyrene microspheres. Additionally, PBS has a degree of polarity that facilitates the dissolution of fluorescent dyes and the dispersion of the microspheres. While physiological saline demonstrated poorer collection efficiency in microbial sampling experiments, it offers advantages for preserving and handling microbial samples[32].

The comparable collection efficiencies of liquid impingers and cyclone separators reported by Chang et al.[13] can be attributed to the combined effects of particle size distribution and sampling medium conditions. Fungal aerosols cover a wide size range (0.5–50 μm); when most particles fall within 5–10 μm, both devices operate near their optimal ranges impingers capture smaller particles (0.5–5 μm) via inertial impaction, while cyclones efficiently separate larger particles (5–20 μm) through centrifugal force. The use of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) in impingers also prevents clogging and enhances recovery of fine particles (< 3 μm), whereas cyclones perform consistently under low humidity (< 60%). Additionally, design optimizations such as modified impinger water columns or electrostatic assistance in cyclones may further narrow performance gaps. Therefore, the convergence in efficiency between these two sampler types is reasonable when particle size and environmental conditions are aligned with their optimal operational ranges.

Impact of sampling flow rate on the sampling efficiency of samplers

-

Sampling flow rate is a critical factor affecting aerosol sampling, significantly impacting the total aerosol quantity and sampling efficiency[49,50]. As the sampling flow rate increases, the sampling efficiency of the wet-wall cyclone sampler also improves. For the membrane filtration sampler, optimal sampling efficiency was achieved at a sampling flow rate of 50 L/min. The sampling efficiency of the wet-wall cyclone exhibited a non-linear relationship with flow velocity. When phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and RNase-free water were used as collection media, a decline in sampling efficiency for both particle sizes was observed at a flow rate of 300 L/min compared with 250 L/min. During the experiments, increasing the flow rate led to noticeable evaporation of the collection liquid, likely reducing the adequate collection volume and particle retention. Consequently, the number of microorganisms captured did not increase proportionally with flow rate and, under certain high-flow conditions, even declined.

This result can be explained in several ways. As the flow rate of the cyclone sampler increases, the high-speed airflow can cause the aerosolized particles absorbed by the liquid to atomize and disperse[51]. Additionally, environmental factors such as temperature and humidity during long-term sampling can induce turbulence and bubble formation in the liquid. These factors can hinder the liquid and the target substances in the air, thereby reducing absorption efficiency. Furthermore, evaporation and re-aerosolization are more likely to occur over time, further affecting sampling efficiency[45]. Finally, as more sampling of liquid is lost, the risk of re-aerosolization of previously captured particles increases.

Physical sampling efficiency of the four samplers

-

Among the four samplers tested, the membrane filtration sampler had the highest overall sampling efficiency for particles ≤ 1 µm in diameter. The sampling efficiency of the membrane filtration sampler increased with the sampling flow rate. However, neither the liquid impinger nor the dry-wall cyclone samplers achieved a sampling efficiency of 50% for microspheres with a diameter ≤ 1 µm, consistent with findings from previous studies[52]. The wet-wall cyclone sampler shows improved sampling efficiency at higher flow rates, consistent with the results of Cho et al.[53]. However, the sampling efficiency of the wet-wall cyclone sampler for microspheres with diameters ≤1 µm remained below 50%.

A comprehensive analysis of results from two experiments revealed minimal differences in sampling efficiency across the four samplers when evaluated using particle counters. In contrast, fluorescence intensity measurements from the fluorescence detector indicated that, under three different sampling flow rates, the membrane filtration sampler exhibited significantly higher fluorescence intensity than the other samplers. When using a particle counter, the sampling efficiency of the membrane filtration sampler for 0.3 µm particles was found to be 2.47% to 16.21% higher than the other samplers across three flow rates. Specifically, at the membrane filtration sampler's sampling flow rate of 30 L/min, the wet-wall cyclone sampler at flow rates of 200, 250, and 300 L/min showed higher sampling efficiency for 1 µm particles by 7.61%, 8.89%, and 10.2%, respectively.

At a sampling flow rate of 40 L/min, the wet-wall cyclone sampler at 200, 250, and 300 L/min exhibited higher sampling efficiency for 1 µm particles by 2.15%, 3.43%, and 4.74%, respectively. These results, however, differed from the fluorescence detector measurements.

During the experimental process, careful calibration of both the fluorescence detector (Supplementary Figs S1–S3) and particle counter was ensured. The membrane treatment procedure in the membrane filtration sampler was also designed to prevent fluorescence contamination. The discrepancies observed in the two experiments may be attributed to differences in the performance and measurement principles of the two instruments. Particle counters typically detect particles using sensors such as light-scattering or laser-scattering sensors, and their efficiency can be reduced when detecting small or irregularly shaped particles[54]. Particle counters are influenced by particle size and shape, and detection efficiency may decrease when testing small, irregularly shaped particles[55,56]. Furthermore, when particle concentrations are low, it may take longer to collect enough particles, potentially affecting sampling efficiency. On the other hand, fluorescence detectors are often more accurate in identifying and measuring target substances.

Although this study primarily evaluates the physical sampling efficiency of the samplers, it should be noted that physical and biological collection efficiencies are not always correlated. Physical sampling efficiency reflects a sampler's capacity to capture airborne particles based on size, shape, and density, whereas biological collection efficiency also depends on microbial viability after sampling. Airborne microorganisms can lose viability due to desiccation, UV exposure, or chemical stress, resulting in lower biological recovery despite high physical capture rates.

This discrepancy arises because non-biological test particles are uniform and inert, while microorganisms vary in morphology and surface properties, such as capsules or flagella, that influence adhesion and retention. Environmental factors further contribute: high humidity supports microbial survival, whereas low humidity promotes desiccation and inactivation—conditions that have minimal effect on inert particles. In this study, an optical particle counter was employed to quantify physical sampling efficiency, as electron microscopy and flow cytometry require complex preparation or are less suitable for airborne particle analysis. The optical approach provides direct, real-time assessment of particle capture performance.

It is important to note that there is a disparity between the environmental conditions within the experimental chamber and those in real-world settings. Therefore, conducting on-site experiments is recommended to further validate the reliability and generalizability of the findings. This highlights the importance of considering environmental factors when applying experimental results to practical scenarios and advocating for more field validations to ensure the robustness of the conclusions.

Study limitations

-

This study used fluorescent microspheres (0.3, 0.5, and 1 μm) as model aerosols; however, they cannot fully represent the diversity and complexity of real bioaerosols, which differ in size, shape, surface properties, and biological activity—all factors influencing airborne behavior and sampler capture efficiency. Future work should include biologically relevant materials to simulate real microbial aerosols better.

Zeta potential measurements were not performed for microspheres in the three collection media, limiting the ability to verify whether their surface charge characteristics accurately mimic those of bacteria and viruses. Because surface charge strongly affects sampler–particle interactions, this omission introduces uncertainty in the generalizability of the results. Incorporating Zeta potential analysis in future studies would improve the validity of microsphere-based models.

The experiment assumed consistent aerosol losses during atomization, though in practice, particles may adhere to chamber walls or sampler surfaces. Environmental parameters such as temperature, humidity, and airflow were not fully controlled, which may affect efficiency. While particle counters provide quantitative, real-time data, they cannot distinguish viable from non-viable particles, may misclassify aggregates, and have limited sensitivity at low concentrations.

Finally, this chamber-based study used high aerosol concentrations in a confined space. Real-world factors such as UV exposure, ventilation, and human activity can substantially influence sampling outcomes[57]. Field validation is therefore essential to assess practical sampler performance.

-

Among the four tested devices, the membrane filtration sampler proved most effective for capturing indoor airborne particles ≤1 μm. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was identified as the optimal medium for liquid-based samplers. Sampling flow rate strongly influenced performance: higher rates improved efficiency for wet-wall cyclone and membrane samplers but reduced it for liquid impingers due to aerosol atomization. These results provide practical guidance for indoor air quality and microbial aerosol monitoring. For long-term or large-scale applications, high-flow samplers may be more practical. Further field validation is recommended to confirm these findings under real-world conditions.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/biocontam-0025-0011.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization, formal analysis, writing − original draft: Zhu Y; methodology: Zhu Y; Peng S; investigation: Peng S; writing − review & editing: Peng S, Ma K, Yang H, Ding Z; resources, data curation: Xu B; validation: Ma K, Yang H; funding acquisition, supervision: Ding Z. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets used or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

This work was supported by the Medical Science and Research Project funded by the Jiangsu Commission of Health (Grant Nos ZD2021021 and M2022069).

-

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

-

Explore the sampling efficiency of four samplers under different sampling conditions.

Membrane filtration sampler is recommended for capturing indoor particulate (≤ 1 µm).

Liquid sampler performs well in collecting particles when using PBS.

Provide technical guidelines for field sampling of airborne microorganisms.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Yuanyuan Zhu, Shifu Peng

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article. - The supplementary files can be downloaded from here.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu Y, Peng S, Xu B, Ma K, Yang H, et al. 2025. Efficiency and performance of microbial aerosol samplers: insights from a controlled chamber study. Biocontaminant 1: e012 doi: 10.48130/biocontam-0025-0011

Efficiency and performance of microbial aerosol samplers: insights from a controlled chamber study

- Received: 25 September 2025

- Revised: 01 November 2025

- Accepted: 14 November 2025

- Published online: 28 November 2025

Abstract: Indoor airborne microorganisms significantly influence human health and indoor environmental quality. This study investigates the performance of four types of microbial aerosol samplers under controlled chamber conditions. Fluorescent microspheres with diameters of 0.3 and 1 μm were used as surrogates for microbial aerosols, and their concentrations were measured by fluorescence detection. Four widely used sampler types were assessed: liquid impinger (10 L/min), dry-wall cyclone (400 L/min), membrane filtration (30, 40, and 50 L/min), and wet-wall cyclone (100, 150, 200, 250, and 300 L/min). Additionally, three liquid media—phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), irradiated physiological saline, and RNase-free water—were evaluated for samplers that utilize liquid collection, excluding membrane filtration. Results demonstrated that the membrane filtration sampler achieved significantly higher fluorescence intensity (390.80 fluorescence standard units) compared to the other samplers (60.31 fluorescence standard units), indicating superior sampling efficiency. Among the liquid-based samplers (liquid impinger, dry-wall cyclone, and wet-wall cyclone), PBS yielded the highest fluorescence intensities. Overall, these findings highlight membrane filtration as the most efficient method for mechanical collection of submicron surrogate particles under controlled conditions, though further studies are required to evaluate biological recovery.