-

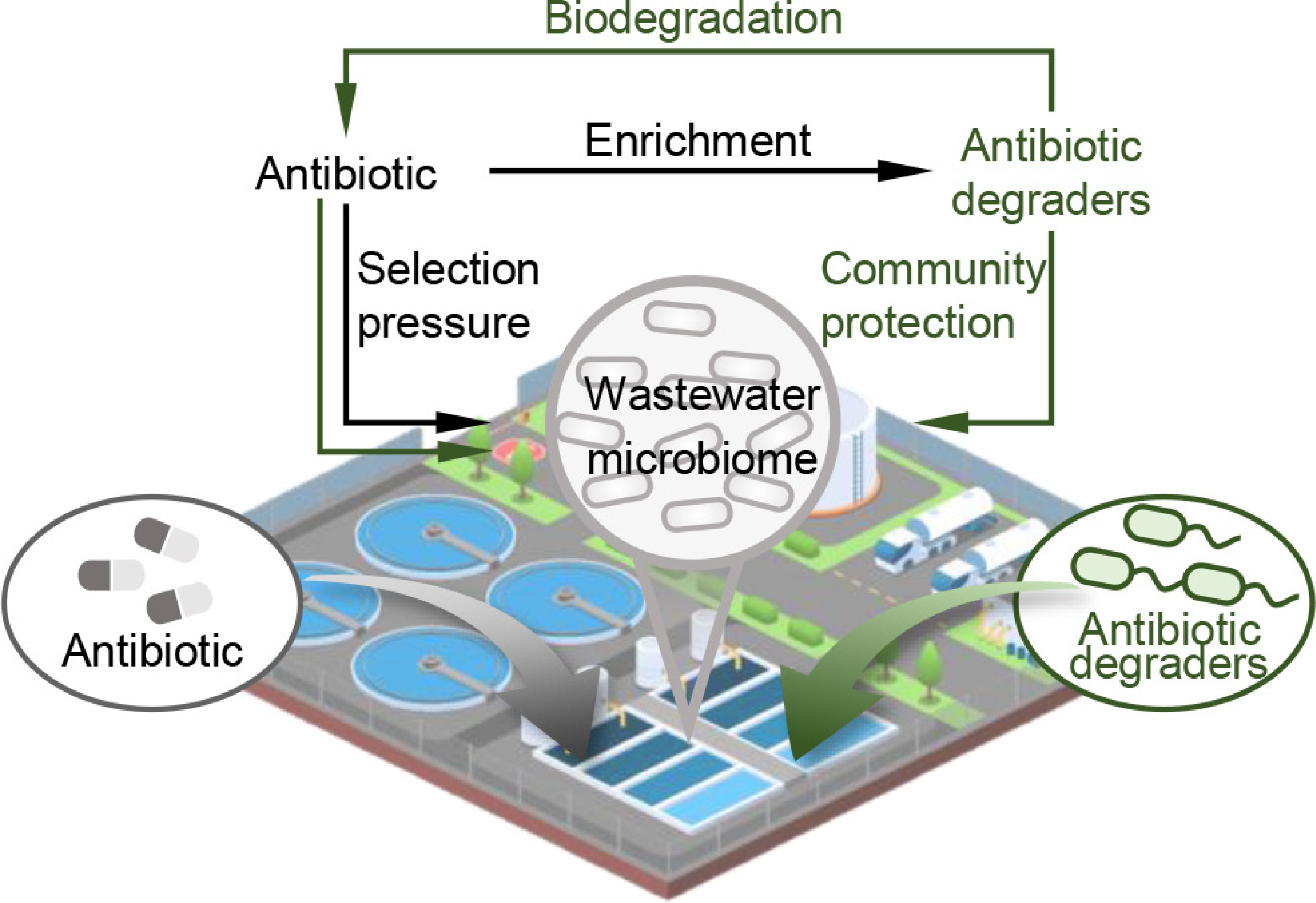

Current environmental risk assessment frameworks for emerging organic contaminants increasingly recognize that uniform vulnerability assumptions across recipient ecosystems may be inadequate, as microbial communities function not merely as passive targets but as dynamic mediators of contaminant fate and toxicity[1,2]. This contaminant-centric paradigm overlooks a critical reality that identical pollutants can pose significantly different environmental risks depending on the intrinsic characteristics of recipient microbial communities, particularly their capacity for contaminant biodegradation[3]. Among emerging contaminants, antibiotics represent a paradigmatic case in which this oversight becomes particularly problematic[4−6], as their environmental impacts are not solely determined by concentration and intrinsic toxicity, but are critically modulated by the presence and activity of antibiotic-degrading microorganisms within recipient communities[7].

Antibiotics enter wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) through multiple pathways, including the use of human and veterinary pharmaceuticals and hospital effluents[8−10]. Despite partial removal during treatment processes, residual concentrations of antibiotics persist in activated sludge systems, typically ranging from ng/L to mg/L levels[11−14]. A comprehensive risk assessment of 3,466 compounds, across 83 studies, identified sulfamethoxazole (SMX) as a top-priority emerging contaminant for removal[14]. SMX typically occurs in aquatic environments at ng/L−μg/L levels; however, upper-bound concentrations have been reported in pharmaceutical wastewater (1.43 mg/L)[15] and, on rare occasions, in municipal wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) effluents (up to 2 mg/L)[16]. These persistent environmental concentrations impose continuous selection pressure that favors resistant microorganisms while suppressing sensitive taxa, ultimately reshaping community structure and compromising functional stability[17−20]. This pressure can disrupt critical biological processes, including nitrification, denitrification, and phosphorus removal, ultimately affecting wastewater effluent quality and ecosystem stability[21−24].

The heterogeneous distribution of antibiotic biodegradation capacity across ecosystems poses a fundamental challenge for current risk assessment protocols. Antibiotic degraders, though often representing minor fractions of total community abundance, can influence ecosystem-level responses to antibiotic stress through their capacity to alleviate selection pressure and maintain community stability[25−28]. This biodegradation capacity is frequently mediated by specialized inactivating antibiotic resistance genes (inactivating ARGs), such as sadA, which encodes a flavin-dependent monooxygenase that catalyzes sulfonamide degradation via ipso-hydroxylation reactions[29−31]. The sadA gene has been detected extensively in Microbacterium, Arthrobacter, and Paenarthrobacter, with its distribution strictly limited to the Micrococcaceae family[30,32]. Critically, the enzymes encoded by these genes function as 'public goods', creating antibiotic-depleted microenvironments that benefit entire communities, including antibiotic-susceptible populations[33−35].

This community-protective function of antibiotic degraders reveals a critical gap in existing risk assessment approaches that is the failure to account for recipient community heterogeneity as a primary determinant of environmental risk. Conventional assessments focus exclusively on contaminant characteristics while overlooking the fact that microbiomes with different degrader compositions may experience vastly different selection pressures and ecological impacts from identical antibiotic exposures[35−37]. Recent studies demonstrate that bioaugmentation with antibiotic-degrading bacteria can preserve community diversity and mitigate the evolution of antimicrobial resistance[38,39]. However, the mechanistic understanding of how antibiotic degraders modulate community-level stress responses remains limited. The critical knowledge gap lies in understanding how variations in the presence of antibiotic degraders (whether through natural adaptation or artificial enhancement) translate into differential community protection and stability under antibiotic stress[36]. This understanding is essential for further developing an environmental risk assessment paradigm that recognizes environmental risk as an emergent property of contaminant-microbiome interactions, where degradation capacity acts as a dynamic determinant of the ecological impact realized in recipient communities. Such a framework necessitates moving beyond static, contaminant-centric evaluations toward dynamic assessments that integrate both pollutant characteristics and recipient community degradative capabilities, acknowledging that identical contaminants can pose different risks across ecosystems with varying microbiome compositions.

To address these knowledge gaps, this study hypothesizes that antibiotic biodegradation capacity, mediated by antibiotic degraders carrying inactivating ARGs, can substantially mitigate antibiotic-induced selection pressure and enhance microbial community stability. Furthermore, we propose that different pathways for acquiring biodegradation capacity (natural adaptation versus pre-adaptation/bioaugmentation) will result in distinct outcomes in community stability and stress response. To validate these hypotheses, a controlled bioreactor system was employed to investigate the effects of antibiotic biodegradation on community succession and stability. SMX was selected as a model sulfonamide antibiotic due to its widespread occurrence in wastewater systems and well-characterized biodegradation pathway mediated by specific SMX-degrading genes and degraders. Through comprehensive analysis of community structure and diversity dynamics, this study aims to illuminate the protective and regulatory roles of antibiotic biodegradation in maintaining community stability and provide insights for optimizing antibiotic environmental risk assessment and management.

-

Community evolution experiments were conducted in laboratory-scale sequencing batch reactors (SBRs), with a working volume of 180 mL, and an aspect ratio of 0.5, inoculated with wastewater-activated sludge. These reactors were operated at room temperature (25 ± 1 °C). The pH was maintained at 7.2 ± 0.2, and the dissolved oxygen (DO) concentration was kept between 2.0 and 3.0 mg/L during the aeration phase. The experimental design included four treatment groups with four replicates per group, aiming to compare evolutionary trajectories under SMX selection pressure: natural adaptation and pre-adaptation. In natural-adaptation communities, reactors were inoculated solely with the original activated-sludge microbiome, without exogenous SMX-degrading bacteria, to observe the spontaneous development of endogenous SMX-degradation capacity and associated community succession under antibiotic stress. For pre-adapted communities, Paenarthrobacter sp. strain M5 (an SMX-degrading strain isolated from activated sludge) was inoculated at an initial cell density of 9.89 × 106 colony-forming units (CFU). Groups were designated using a two-letter code: the first letter denotes SMX treatment status (S represents SMX addition, N represents no SMX addition), and the second indicates bioaugmentation status (M means strain M5 inoculation, N means no inoculation).

The bioreactors were operated aerobically in the following sequential phases: Phases T1–T4 (Acclimation): The natural adaptation (SN) and pre-adaptation (SM) groups were exposed to progressively increasing SMX concentrations (2, 5, 10, and 20 mg/L) to establish SMX-degradation capacity. The concentration steps were justified by the highest SMX levels reported in WWTP effluents (up to 2 mg/L), ensuring that reactors were challenged above environmental maxima and enabling evaluation under realistic-to-worst-case exposures. The progressive escalation of concentrations was designed to simulate a scenario of steadily worsening contamination. Phase T5 (Recovery): No SMX was added to any group to monitor microbial community recovery. Phase T6 (Re-exposure): all groups were re-exposed to 20 mg/L SMX to evaluate the degradation performance and community successional dynamics during secondary antibiotic contamination. Each experimental phase (T1−T6) lasted for 14 d, consisting of 28 operational cycles of 12 h each. The total operation time for the reactors was 84 d. Every reactor was supplied with synthetic wastewater containing glucose (350 mg/L), NH4Cl (30 mg/L, calculated as NH4+-N), NaNO3 (10 mg/L, calculated as NO3−-N), KH2PO4 (10 mg/L, calculated as PO43−-P), and NaHCO3 (20 mg/L). The medium was supplemented with Wolf's trace element solution at a dosage of 10 mL/L.

In situ and ex situ SMX degradation analysis

In situ monitoring of SMX degradation

-

SMX degradation was assessed using a two-tier analytical framework that combined operational monitoring and standardized biodegradation assays. Operational monitoring: SMX concentrations were tracked throughout reactor cycles by sampling at feed introduction and cycle completion, providing real-time degradation performance data.

Ex situ biodegradation potential assays

-

At each phase endpoint, 2 mL of mixed liquor samples underwent standardized processing: centrifugation for biomass recovery, washing for substrate removal, and resuspension in 1 mL of synthetic wastewater. The concentrated biomass was subsequently exposed to 50 mg/L SMX in 4 mL of fresh synthetic wastewater under standardized incubation conditions (30 °C, 8-h duration).

Analytical methodology

-

Immediately after collection, samples were filtered through 0.22-μm membrane filters prior to analysis. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC, Agilent 1260 Infinity) quantified SMX concentration equipped with a ZORBAX SB-C18 column (4.6 mm × 150 mm, 5 μm). Isocratic elution at 1.0 mL/min was used with a binary mobile phase of 85% ultrapure water (0.1% formic acid), and 15% acetonitrile. The column was maintained at 30 °C, and the injection volume was 10 μL. The detection wavelength was 275 nm, and the SMX retention time was approximately 12 min under these conditions. SMX degradation efficiency (%) was calculated as (C0 − Ct)/C0 × 100%, where C0 and Ct denote the initial and final SMX concentrations, respectively[40].

DNA extraction and 16S rRNA gene analysis

-

Community DNA for 16S rRNA gene sequencing was obtained through standardized sampling at experimental phase boundaries (initiation and termination). The collection methodology involved harvesting 2 mL of homogenized activated sludge, 2 h after medium replenishment, centrifuging the biomass (12,000 rpm, 5 min), and collecting the pellet. Genomic DNA was isolated using previously described methods[41]. DNA quality metrics were evaluated using UV-visible spectrophotometry (A260/A280) and electrophoresis.

Genomic DNA was used as a template for PCR amplification targeting the V4 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene to identify bacterial diversity. PCR amplification was performed using barcoded primers and PremixTaq (TaKaRa) according to the selected sequencing region. Following purification, PCR products were subjected to library construction and subsequently sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform. Detailed protocols are provided in the Supplementary Text S1[40].

Statistical analysis

-

All experiments were performed in quadruplicate. α diversity, β diversity, and community similarity analyses were performed using the vegan package in R Studio (v4.0.3). For α-diversity analysis, nonparametric statistical tests were employed because the diversity indices were not normally distributed. Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to evaluate overall group differences at each experimental phase, with subsequent Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for pairwise comparisons when the omnibus test was significant (p < 0.05). The Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) procedure was applied to adjust p-values for multiple testing.

Community structural differences among treatments were evaluated using three complementary methods: Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance (Adonis), Analysis of Similarities (ANOSIM), and Multi-Response Permutation Procedures (MRPP). Adonis quantifies the proportion of variance explained by treatment effects; ANOSIM evaluates the significance of differences using R statistics; MRPP tests whether within-group similarities exceed those expected by chance. To characterize community succession dynamics, evolutionary trajectory analyses were used to calculate inter-sample distance matrices and visualize temporal trajectories[42,43].

-

A SMX-degrading bacterial strain, designated as Paenarbrobacter sp. M5 was successfully isolated from activated sludge by continuous subculture using SMX as the sole carbon source. It exhibited 100% 16S rRNA gene similarity to Paenarthrobacter ureafaciens. Strain M5 completely degraded 30 mg/L SMX within 10 h, producing an equimolar amount of 3-amino-5-methylisoxazole (3A5MI) as the primary end-product and harboring the key degradation gene sadA (Supplementary Fig. S1a). The degradation pathway involves ipso-hydroxylation, generating non-antibacterial intermediates p-aminophenol and 3A5MI. The p-aminophenol can be further metabolized and utilized by strain M5 for growth[40]. This process relied on a two-component enzyme system comprising the flavin-dependent monooxygenase SadA and the FMN flavin reductase SadC, which mediated SMX hydroxylation and cleavage of the -C-S-N- bond[29].

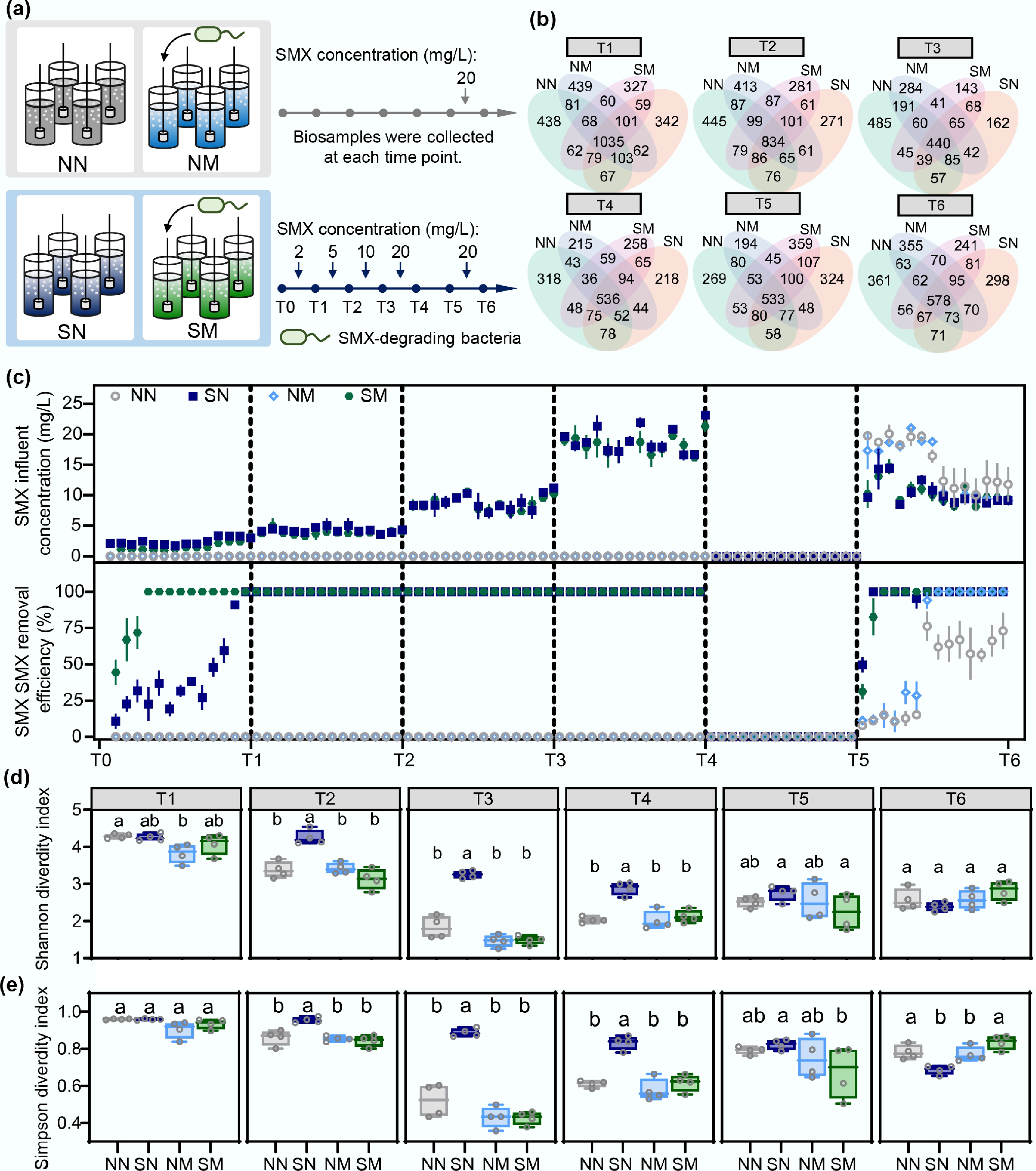

To ensure controlled experimental conditions, strain M5 was inoculated under defined antibiotic stress to investigate how differences in antibiotic degradation capacity influence microbial community succession, as shown in the experimental design (Fig. 1a). Four treatment groups were established: NN (control, without SMX), SN (natural adaptation upon SMX stress), NM (M5 inoculation without SMX), and SM (pre-adaptation with M5 inoculation upon SMX stress). Inoculation of SMX-degrading bacterium strain M5 shaped differential SMX degradation profiles among microbial communities (Fig. 1b). During the initial phase (T1, 2 mg/L SMX), naturally adapted communities (SN) progressively acquired SMX biodegradation capacity over 28 cycles. In contrast, pre-adapted communities (SM) exhibited immediate and efficient SMX degradation upon inoculation with strain M5. As SMX concentrations increased, both SMX-exposed communities ultimately achieved complete SMX removal, demonstrating that the inherent antibiotic biodegradation could be induced under sustained selection pressure regardless of bioaugmentation. To evaluate community resilience, SMX addition was temporarily halted (T5) to simulate intermittent exposure, followed by reintroduction of high SMX concentrations (T6). While the control community (NN) achieved approximately 70% SMX degradation, its performance varied considerably among replicates. In contrast, the other communities rapidly regained their degradation capacity with recovery efficiency following the order SN > SM > NM, highlighting how different evolutionary conditions influence functional stability and community resilience to antibiotic perturbation.

Figure 1.

SMX stress and degradation capacity jointly drive community α diversity change dynamics. (a) Experimental design: Two treatment strategies were established to compare community responses to SMX stress. Natural adaptation groups: no degrading bacteria added, observing autonomous evolution (NN: control without SMX; SN: SMX treatment); Pre-adaptation groups: degrading bacteria pre-inoculated, exploring effects of initial degradation capacity (NM: control without SMX; SM: SMX treatment). (b) Shared and unique OTU distribution among treatment groups. (c) SMX concentrations in influent and removal efficiencies during operation period. (d) Shannon and (e) Simpson diversity index variations and statistical differences between groups. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05).

Experiments were conducted ex situ to highlight the differences in antibiotic biodegradation capabilities among various groups, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S2. The degradation effectiveness of the natural adaptation (SN) group improved progressively over time, ultimately achieving removal efficiencies of 36.3%, 62.3%, and 100% at SMX concentrations of 2, 5, and 10 mg/L, respectively. This concentration-dependent enhancement is consistent with reports on sediment microbial communities, where sulfamethazine biodegradation increases at higher exposure concentrations[44]. Moreover, continuous SMX exposure reshapes community composition and transiently suppresses specific functions; upon acclimation, biodegradation performance recovers and may even be enhanced[45]. The pre-adaptation group (SM) demonstrated immediate and complete degradation efficiency throughout all testing phases, irrespective of SMX concentration. In contrast, the natural adaptation control (NN) exhibited limited degradation capacity (12.2%–16.6%), while the pre-adaptation control (NM) showed a declining trend from 30.5% to 13.4%. This indicates that antibiotic exposure is a critical driver for antibiotic degradation in natural communities, highlighting the substantial potential of indigenous microorganisms to mitigate contaminant stress. Concurrently, antibiotics represent the main factor promoting colonization by the bioaugmented strain M5, whereas they diminished and lost their environmental influence without selection pressure.

Differential community diversity response during the SMX degradation process

-

To investigate microbial community succession under different evolutionary conditions, 16S rRNA gene sequences from samples collected at each reactor phase were analyzed. Community biodiversity was analyzed based on operational taxonomic units (OTUs), and shared vs unique OTU distributions were examined (Fig. 1c). All treatment groups maintained a core set of shared OTUs, regardless of SMX exposure or bioaugmentation, likely representing functionally essential microbial populations. These core communities presumably performed fundamental wastewater treatment functions (carbon/nitrogen metabolism) while maintaining system stability. During the initial start-up phase (T1), 1,035 OTUs were shared among all testing groups, indicating a highly similar initial microbial community structure. During T1 and T3, the number of shared OTUs dropped sharply to 440, reflecting substantial community restructuring. From T4 to T6, shared OTU numbers stabilized between 533 and 578, suggesting that the communities had reached a more stable, resilient state.

Further analysis of community α-diversity revealed distinct temporal dynamics among the groups (Fig. 1d). During T1, community diversity was relatively similar across groups. As SMX concentrations increased during T2–T4 phases, naturally adapted communities (SN) maintained significantly higher Shannon diversity indices (0.76−1.76) than pre-adapted communities (SM), with the difference ranging from 0.76 to 1.76 (p < 0.05). In the recovery phase (T5), differences in diversity narrowed (p > 0.5). Upon re-exposure to SMX (T6), α-diversity indices of all testing groups converged to comparable levels, with no significant differences observed. The trends in α-diversity, corroborated by both the Shannon and Simpson indices (Fig. 1e), revealed a consistent pattern: an overall decline from phase T2 to T4, with the SN group showing a significantly smaller decline than the other groups (p < 0.05). This temporal dynamic illustrates a coherent adaptive progression involving initial differentiation, major structural reorganization, and eventual attainment of a new equilibrium under antibiotic pressure.

Interestingly, introducing SMX degrader under antibiotic exposure seemed to reduce diversity in pre-adapted communities, creating profiles resembling those under no selection pressure (Supplementary Fig. S3). Conversely, limited SMX exposure preserved higher microbiome diversity in natural adaptation scenarios, with Shannon and Simpson indices significantly higher than those in pre-adapted communities. Although antibiotic stress typically reduces microbiome diversity[46−49], it is proposed that this counterintuitive pattern arises because diversity naturally declines during community succession. The slower antibiotic biodegradation in naturally adapting communities delays successional progression, thereby maintaining higher diversity. Subsequent analyses further supports this interpretation.

SMX stress and biodegradation synergistically determine community succession

-

To quantify structural variations in microbial communities, multiple statistical analyses were applied to compare community dynamics across treatment groups (Supplementary Table S1). Specifically, ADONIS was used to quantify the proportion of community variation explained by treatment factors (R2), while MRPP was employed to test whether differences between predefined groups were statistically significant. First, the effect of SMX stress was examined by comparing the naturally adapted (SN) and control (NN) groups. This revealed a significant, dose-dependent impact of SMX on community structure, with divergence intensifying during the initial exposure (T1–T4) (ADONIS, R2 = 0.438–0.607, p < 0.05). Although this divergence lessened during the recovery phase (T5), it remained significant (p < 0.05), suggesting persistent antibiotic effects. Upon secondary SMX exposure (T6), structural divergence increased again (ADONIS, R2 = 0.582, p < 0.05), demonstrating stable structure and rapid response capability in the naturally adapted group.

In contrast, the protective role of bioaugmentation was evident when comparing the pre-adapted (SM) and control (NN) communities. Throughout most of the experiment (T1–T5), no significant differences were observed between these groups (ADONIS, R2 = 0.122–0.339, p > 0.05). This unremarkable similarity demonstrates that inoculating SMX degraders effectively buffered the community from antibiotic-induced structural shifts. A significant difference emerged only in the final phase (T6; p < 0.05), suggesting that secondary exposure may have triggered subtle adaptive succession even in the protected community.

Taken together, these results indicate that community succession is jointly regulated by antibiotic pressure and enhanced biodegradation. The protective effect was most pronounced when comparing the pre-adapted (SM) and naturally adapted (SN) groups: the SM community remained structurally similar to the unstressed control (NN), whereas the SN community had diverged significantly. This offers clear mechanistic insight into the ecological role of antibiotic degraders and holds substantial implications for optimizing wastewater treatment and ensuring microbiome stability under antibiotic stress.

To elucidate the taxonomic basis of these shifts, we examined the temporal dynamics of relative abundance at the order level across treatment groups (Supplementary Fig. S4). During the initial phase (T0−T1), communities across all treatment groups shared a similar composition, dominated by Betaproteobacteriales (β-proteobacteria) and Anaerolineales, with minor Rhizobiales, reflecting the original microbial profile of the inoculated sludge. In T2, community compositions began to diverge significantly. Proportions for Saccharimonadales and Betaproteobacteriales increased markedly (p < 0.05) across all treatment groups, emerging as dominant taxa. However, these two orders showed significantly lower abundances in the SN group than in the other groups (p < 0.05). Concurrently, the abundances of Betaproteobacteriales and Anaerolineae began to decline. The inoculation of strain M5 enriched Micrococcales (the order containing the SMX degrader) by 0.0043 (proportion). This inoculation effect amplified during the T1 period, with Micrococcales reaching relative abundances of approximately 0.25 in both NM and SM groups. In contrast, due to SMX selection pressure, this taxon maintained a relative abundance of approximately 0.12 in the SN group. Throughout subsequent community succession, its abundance gradually stabilized.

At the genus level (Fig. 2a), microbial communities transitioned from generalist metabolizers to specialized functional taxa. During the initial phase (T0–T1), Hyphomicrobium dominated all treatment groups due to their broad metabolic capabilities and adaptability to diverse environmental conditions. In the strain M5 inoculated treatment groups (NM and SM), genera such as SM1A02 and Thauera were enriched. SM1A02 participates in nitrification processes, while Thauera degrades nitrogen-containing heterocyclic compounds (such as the isoxazole ring structure in SMX, which is detected during degradation and subsequently further degraded)[50]. Their enrichment likely stems from: (1) direct involvement in SMX degradation pathways (e.g., assisting antibiotic degraders in further transformation of intermediates); and (2) benefiting from the protective effect conferred by degraders reducing antibiotic stress.

Figure 2.

Dynamic changes in species composition during different microbial community succession processes. (a) Temporal changes in relative abundance of microbial communities at genus level across different treatment groups. (b) Abundance changes of key degrader genera during SMX degradation. 'P-Unassigned' and 'M-Unassigned' represent unassigned genera within the families Micrococcaceae and Microbacteriaceae, respectively. (c) Importance analysis of key genera in microbial communities based on random forest algorithm.

In natural adaptation, Lysobacter demonstrated a clear competitive advantage as an ordinary member of activated sludge[51]. Simultaneously, Nitrospira, a typical nitrifying bacterium (involved in nitrite oxidation), was significantly enriched in the SN group compared to others (p < 0.05). During prolonged operation (T5–T6), Rudaea and Kineosphaera showed enrichment trends across different treatment groups. Both genera exhibit strong environmental resilience, including tolerance to antibiotic residues and adaptation to glucose-based growth conditions over extended periods.

Microorganisms capable of degrading SMX primarily include members of Paenarthrobacter (Micrococcaceae) and Microbacterium (Microbacteriaceae)[52]. The abundances of these important genera are shown in Fig. 2b. At the initial stage (T0), Paenarthrobacter abundance was significantly higher in pre-adapted communities than in naturally adapted communities, confirming successful colonization of the inoculated strain M5. Concurrently, low initial abundances of indigenous degraders in naturally adapted communities indicated an intrinsic potential for SMX degradation. In T1, SMX degrader abundance increased across the treatment groups, with more pronounced increases in the SN and SM groups (under SMX stress), where Paenarthrobacter reached relative abundances of 24% and 19%, respectively, compared to 7% and 8% in the NN and NM groups. This apparent difference demonstrates that SMX selection pressure is the key driver of enrichment of specific degrader genera (particularly Paenarthrobacter).

Throughout T2−T4, as SMX concentrations increased, Paenarthrobacter maintained high abundance (4%–5%) in the naturally adapted group (SN), far exceeding the control group NN (0.1%–0.5%), indicating stable degrader niches under sustained selection. In the pre-adapted group (SM), Paenarthrobacter abundance was 1%–2%, lower than in the SN group but higher than in the NN and NM groups. This suggests potential competition between exogenous and indigenous degraders, though SMX selection pressure remained the primary driver of degrader enrichment. In later stages (T5–T6), Paenarthrobacter abundance differences among treatment groups gradually diminished. Additionally, while overall abundances of Microbacterium and Leucobacter (potential SMX degraders) were low across treatment groups; they increased under SMX pressure-free conditions, further confirming Paenarthrobacter as the core functional genus in SMX degradation. During the secondary antibiotic exposure (T6), all four groups experienced selection pressure, with rapid increases in degrader abundance in SMX-adapted groups (SN and SM). At the same time, even the control group (NN) exhibited degrader enrichment, consistent with initial adaptation patterns. This demonstrates that communities possess inducible antibiotic-degrading capacity, with even short-term SMX pressure activating latent degraders.

To accurately identify the key genera involved in the regulation of SMX degradation and the differentiation of communities throughout the process of succession, a Random Forest classifier was utilized to evaluate the significance of each genus. The algorithm constructs multiple decision trees, using genus abundance contributions to treatment group classification accuracy as the core metric, efficiently screening taxa most sensitive to different treatment conditions. Figure 2c presents genus importance rankings based on Mean Decrease Gini. The Gini coefficient reflects how a genus's abundance changes contribute to distinguishing between communities, with higher coefficients indicating stronger discriminatory power for distinguishing between treatment groups. Among the top 20 most important genera, Paenarthrobacter exhibited the highest importance score, reaffirming its central role in SMX degradation and community succession (Supplementary Fig. S5). Other high-ranking taxa, such as Saccharimonadales and Caldilineaceae, showed significant differences in abundance between treatment groups (p < 0.05) and served as key indicator taxa for distinguishing treatment effects. Mean accuracy decrease, which measures genus importance by the reduction in model classification accuracy after removing a specific genus, yielded results highly consistent with Gini coefficient rankings.

Enhanced biodegradation mitigates SMX stress on community succession

-

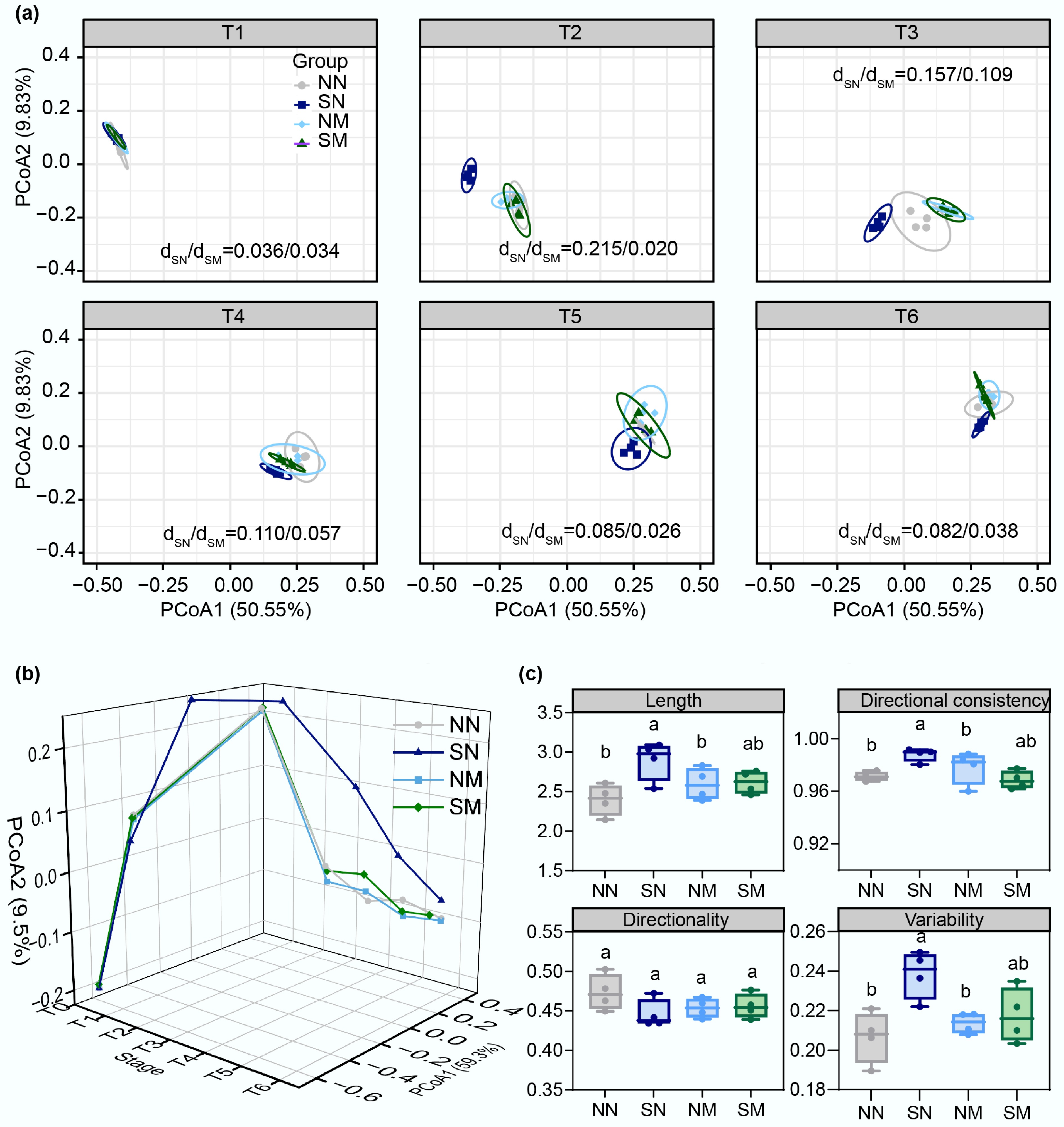

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) at the OTU level revealed dynamic structural shifts across four treatment groups (Fig. 3a). The first principal coordinate (PCoA1) explained 50.55% of community variation, serving as the primary dimension separating treatment groups. Succession proceeded in three distinct phases, reflecting progressive differentiation. Initially, at phase T1, all communities showed high similarity (dSN/dSM = 0.036/0.034), consistent with identical activated sludge inocula and negligible selection pressure from SMX or its degraders. However, early differentiation emerged at phase T2, where the natural adaptation group (SN) rapidly diverged from controls, and the pre-adapted group, with dSN/dSM values increasing to 0.215/0.020. This demonstrated that 5 mg/L SMX significantly altered community structure in SN, while SM maintained proximity to controls due to rapid SMX degradation by strain M5, highlighting the degraders' stabilizing effect. Subsequently, during the stabilization phases (T3−T6), treatment groups formed distinct clusters with reduced differentiation, which persisted even under secondary antibiotic exposure (dSN/dSM values: T5 = 0.085/0.026, T6 = 0.082/0.038). These results demonstrated that antibiotic pressure and degrader inoculation collectively drove community succession, with enhanced degradation capacity explaining the observed structural dynamics.

Figure 3.

Changes in structural composition and trajectory analysis during microbial community succession. (a) Temporal variation of microbial community structure across treatment groups (analyzed at OTU level using Bray-Curtis distance). Ellipses represent 95% confidence intervals, with dSN/dSM values indicating the ratio of distances between SN and SM group centroids relative to the control (NN) group centroid, quantifying their respective divergence from the control. (b) Community evolution trajectories, and (c) index analysis based on Bray-Curtis distance.

Evolutionary trajectories based on Bray-Curtis distance revealed distinct phase-specific succession patterns (Fig. 3b). All experimental groups exhibited similar upward trends during phases T0−T2. Subsequently, naturally adapted communities diverged markedly from the others, peaking at phase T2 before declining and eventually stabilizing. In contrast, the other groups (NN, NM, SM) maintained similar patterns with minimal variation through phases T3−T6, highlighting the long-term stabilizing effect of antibiotic degraders on community structure under antibiotic stress. Quantitative analysis of Bray-Curtis trajectory parameters revealed that naturally adapted communities (SN) exhibited significantly higher trajectory length, direction consistency, and variability compared to the control (NN) (Fig. 3c). During spontaneous antibiotic degradation evolution, community succession complexity and instability increased substantially, requiring more severe structural reorganization to adapt to antibiotic stress. In contrast, key parameters of pre-adapted communities showed no significant differences from the control (NN and NM), demonstrating that enhanced biodegradation effectively counteracted SMX perturbation on community succession. Euclidean distance trajectory analysis showed no significant differences in trajectory length across groups (Supplementary Fig. S6). However, directional consistency and directionality were significantly higher in naturally adapted communities than in the other three groups (p < 0.05), indicating that limited antibiotic biodegradation altered the direction of succession under SMX selection pressure.

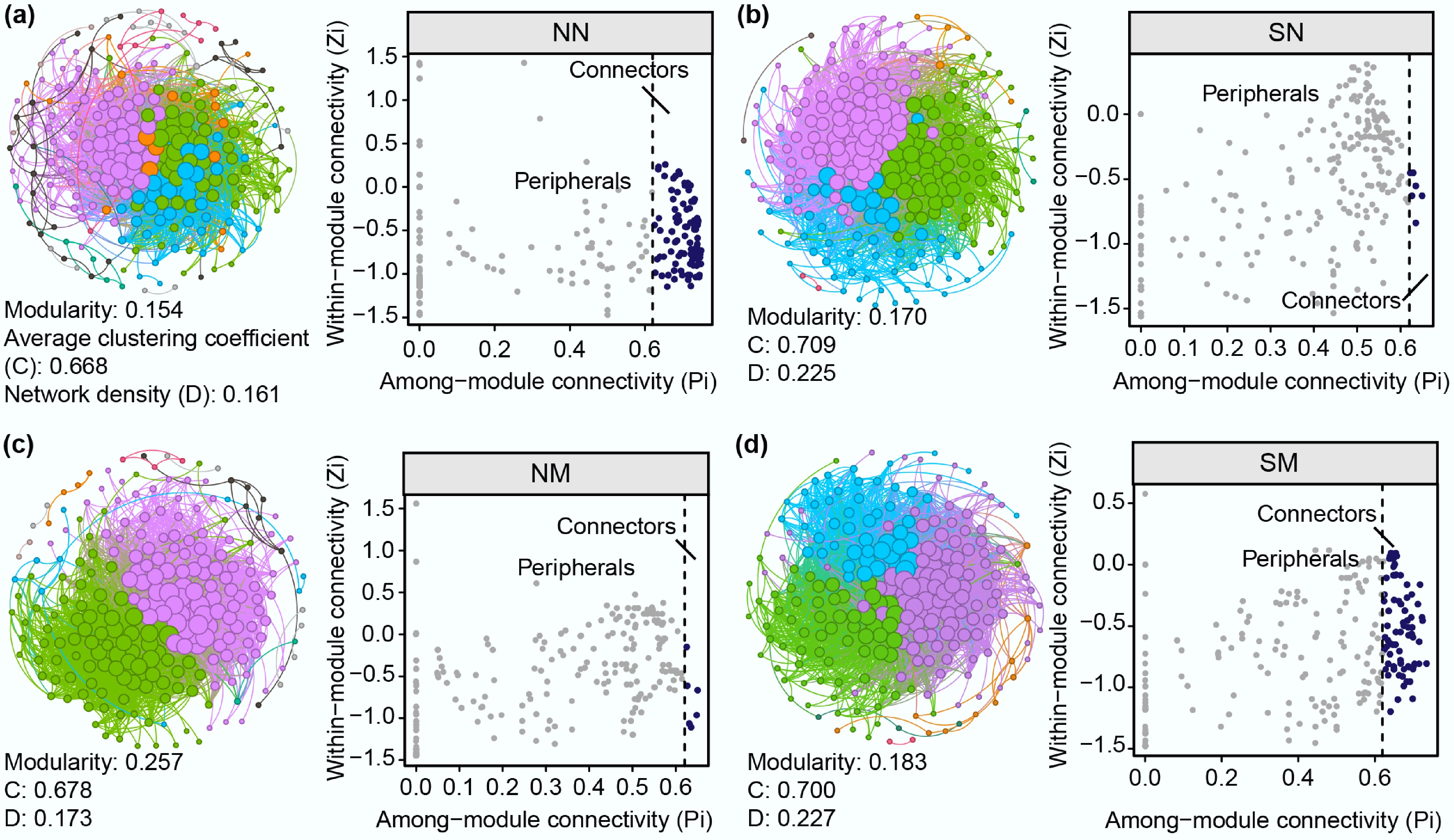

Microbial co-occurrence networks were constructed based on Spearman correlations (|r| > 0.8, p < 0.001) among species (Fig. 4). Despite similar node counts (233−245) across the tested groups, antibiotic-exposed communities (SN and SM) developed more complex network structures with substantially increased edge numbers (SN: 6,081, SM: 6,462) compared to non-antibiotic groups (NN: 4,824, NM: 4,927). This indicates intensified species interactions under selection pressure. Meanwhile, antibiotic exposure enhanced the network integration metrics of naturally adapted and pre-adapted communities, including average degree (SN: 52.2, SM: 54.1), network density (SN: 0.225, SM: 0.227), and clustering coefficients with shorter path lengths (SN: 2.085, SM: 2.208) compared to controls. The proportion of positive correlations decreased in the inoculated groups (SN: 76.4%, SM: 80.8% vs NN: 86.6%, NM: 82.8%), suggesting that degrader introduction increased competitive interactions within the communities.

Figure 4.

Microbial community co-occurrence networks and distribution of topological roles of network nodes across different treatment groups during succession. (a) NN, (b) SN, (c) NM, (d) SM group. Spearman correlation among species with |r| > 0.8 and p < 0.001. Topological role analysis, based on within-module connectivity (Zi), and among-module connectivity (Pi) parameters, classified nodes as peripheral (Pi < 0.60), or connector (Pi ≥ 0.60) nodes.

The control (NN) exhibited the most balanced network structure, characterized by the fewest peripheral nodes (146), and the highest number of connector nodes (99), demonstrating that undisturbed communities maintain efficient inter-module interactions without requiring strong internal connections. Single-disturbance groups (SN and NM) showed significant increases in peripheral nodes (223 and 233, respectively), and sharp reductions in connector nodes (10 and 6, respectively), indicating functional module separation under antibiotic stress or biological disturbance. This likely represents a self-protective mechanism to limit the propagation of adverse impacts. Notably, the SM communities exhibited network characteristics intermediate between the control and single-disturbance groups, with 205 peripheral nodes and 34 connector nodes (significantly higher than in the single-disturbance groups). This reveals that degraders enhance community stability not only by direct SMX degradation but also by fostering inter-module connectivity via connector nodes.

Overall, microbial co-occurrence network analysis revealed how adaptation to antibiotic stress and the development of degradation capacity reshape microbial interactions. Both naturally adapted and pre-adapted communities formed denser, more complex networks characterized by intensified interactions, higher connectivity and density, and more efficient local clustering. These structural enhancements promote community resilience and functional stability in the face of environmental stress. While antibiotic stress disrupts modular interactions, enhanced biodegradation capacity can reconstruct network synergy by modulating connector node abundance. This mechanism represents the structural foundation enabling pre-adapted communities to achieve both efficient antibiotic degradation and structural stability.

Community protection mediated by antibiotic-degrading bacteria

-

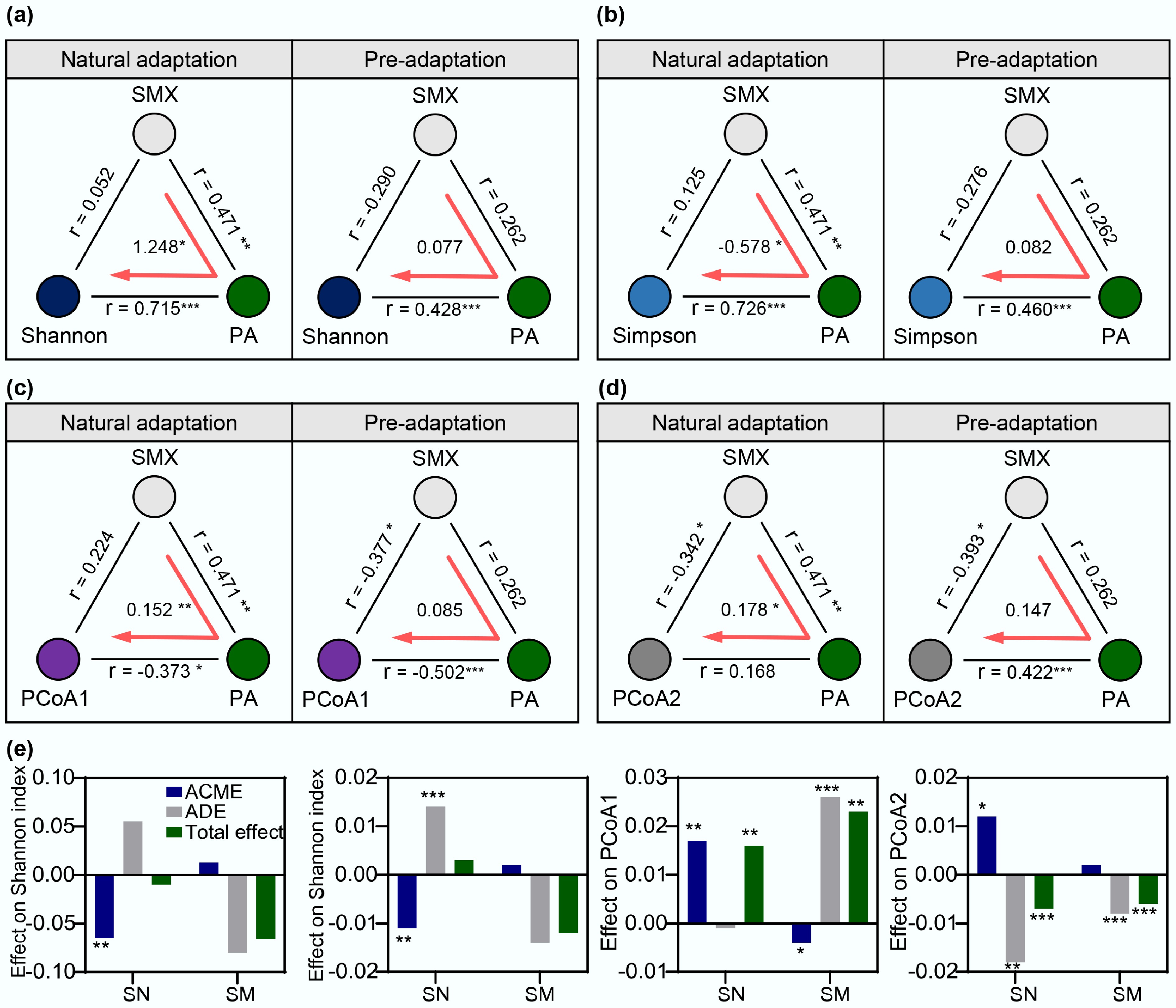

Causal mediation analysis, a classical statistical approach for quantifying how mediator variables transmit effects from independent to dependent variables[53], was employed to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the relationship between SMX degradation and community stability. This approach decomposes total effects into Average Direct Effects (ADE) and Average Causal Mediation Effects (ACME), allowing precise quantification of the relationships among SMX stress, degrader abundance, and community stability. The analysis revealed distinct mediation patterns across community evolution modes (Fig. 5). In natural adaptation (SN), antibiotic degraders exhibited significant mediation effects on Shannon diversity, with an ACME 1.25-fold greater than the total effect (p < 0.01), indicating that the regulatory influence of degraders surpassed the direct antibiotic effects. This finding was corroborated by a strong positive correlation between degrader abundance, and Shannon diversity (rspearman = 0.715, p < 0.001). These degraders harboring inactivating ARGs acted as dynamic regulators that responded to fluctuations in antibiotics while maintaining community diversity under stress, thereby enhancing ecological resilience. In contrast, the pre-adapted communities (SM) exhibited significantly weaker correlation (rspearman = 0.428, p < 0.001), accompanied by non-significant direct and total effects. This indicates a more stable community state characterized by decreased environmental sensitivity. The Simpson index, focused on dominant species, exhibited weaker mediation (−0.578), suggesting limited influence on the structure of dominant taxa. For β-diversity metrics (PCoA1 and PCoA2), degrader-mediated effects were significant but proportionally small, indicating that direct antibiotic effects primarily drove community compositional shifts.

Figure 5.

Mediation effect analysis of degrading bacteria on SMX-induced changes in community structure under two evolutionary modes. Causal mediation effects of SMX concentration and degraders on (a) Shannon diversity index, (b) Simpson diversity index, (c) PCoA1, and (d) PCoA2. r represents the Spearman correlation coefficient. (e) Analysis of ACME, ADE, and total effect of SMX degrader Paenarthrobacter (PA) on each variable. Significance levels are indicated by asterisks: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001.

A single SMX-degrading species, Paenarthrobacter, was sufficient to induce different community responses to antibiotic stress. While these specialized microorganisms typically constitute only a minor fraction of total community abundance, their metabolic capacity for antibiotic degradation provides keystone stability that extends far beyond their numerical representation. By effectively removing antibiotic selection pressure, antibiotic degraders (whether spontaneously enriched or bioaugmented) modulate community-wide evolutionary trajectories and preserve ecosystem-level diversity. Furthermore, the presence of antibiotic-degrading species reshapes microbial community dynamics, preventing antibiotic-induced community collapse and maintaining network connectivity across taxa. Overall, the community protection mediated by antibiotic degraders represents a critical ecological mechanism in which single-species functionality cascades to influence the entire microbiome, highlighting the regulatory role of specialized metabolic capabilities in determining community fate under antibiotic stress.

These findings indicate that controlled pre-adaptation or targeted bioaugmentation with SMX-degrading taxa (e.g., Paenarthrobacter sp. M5) can: (1) rapidly remove SMX to lower antibiotic selection pressure; (2) stabilize essential treatment functions and network connectivity under antibiotic stress; and (3) potentially narrow the window of antibiotic-induced perturbation in WWTPs (e.g., proliferation and dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes). These insights inform WWTP operational strategies (e.g., assessing community biodegradation capacity by detecting antibiotic degraders) to reduce selection pressure and stabilize community succession. Beyond the infrastructure level, they can also support antibiotic risk assessment by explicitly considering biodegradation-mediated attenuation and community resilience.

-

Community protection mediated by antibiotic-degrading bacteria represents a critical ecological strategy for maintaining ecosystem stability under antibiotic stress. Although demonstrated under laboratory-scale conditions using SMX as the model antibiotic, our findings reveal that antibiotic degraders function as biological shields, creating protective microenvironments that buffer the entire microbial community from antibiotic toxicity. This protection extends beyond simple detoxification, encompassing the preservation of functional diversity, maintenance of ecological network integrity, and stabilization of community succession trajectories. The enhanced network connectivity observed in the pre-adapted communities suggests that degraders facilitate interspecies cooperation and resource sharing, thereby fostering a more resilient ecological framework. Furthermore, the reduced environmental sensitivity observed in bioaugmented systems indicates that degrader-mediated protection provides lasting stability, enabling communities to maintain consistent performance even under fluctuating antibiotic concentrations. These protective effects are particularly crucial in engineered biological systems, such as wastewater treatment, where maintaining stable microbial communities is essential for reliable pollutant removal. The ability of degraders to simultaneously neutralize antibiotic stressors and preserve community structure represents a paradigm shift from viewing individual species as isolated functional entities to recognizing them as integral components of community-wide protection networks. This mechanistic understanding provides a theoretical foundation for developing targeted bioaugmentation strategies that enhance both treatment performance and system resilience in antibiotic-contaminated environments. However, as these conclusions were drawn from a lab-scale system using a single model antibiotic, future large-scale investigations are needed to validate these protective effects in real-world scenarios and to elucidate further the quantitative relationship between degrader abundance and the resulting degree of community protection.

These findings have important implications for antibiotic environmental risk assessment and management. Traditional risk evaluation frameworks primarily emphasize antibiotic characteristics and direct toxicological effects, overlooking the critical role of antibiotic degraders in modulating community-level stress responses. The present results highlight that the presence and abundance of antibiotic degraders within stressed communities can substantially modify the magnitude of antibiotic impact, suggesting that microbial degradation potential should be incorporated as a key parameter in environmental risk assessments. Because degrader populations vary across environmental matrices, identical antibiotic concentrations may elicit different ecological consequences depending on the indigenous or bioaugmented degradation capacity of recipient communities. This paradigm shift calls for the development of community-based risk assessment models that integrate both chemical exposure and biological mitigation capacity. Incorporating these elements will enable more accurate predictions of antibiotic impacts on microbial ecosystems and support the design of more effective, biologically informed remediation strategies.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/biocontam-0025-0016.

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study design, data analysis and interpretation of results, and writing original draft: Li-Ying Zhang; analytical testing and manuscript review: Qian Li, Gen-Ping Yi; analysis and interpretation of results: Han-Lin Cui, Yaru Liu, Ke Shi, Bo Wang; study conception and draft manuscript preparation: Bin Liang, Ai-Jie Wang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The 16S rRNA gene sequencing data for all biological samples here are available in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Data can be accessed using BioProject Accession No. PRJNA1304699, with individual sample Accession Nos SAMN50560203 and SAMN50554012–SAMN50554114.

-

The study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52322007), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (Grant No. 2023B1515020077), and Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (Grant No. JCYJ20240813105125034).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Antibiotic stress and biodegradation jointly drive the succession of the wastewater microbiome.

Antibiotic degraders provided community protection 1.25-fold stronger than direct antibiotic effects.

Pre-adapted communities achieve rapid antibiotic degradation and superior resilience.

Bioaugmentation strategy effectively safeguarded the microbiome under antibiotic stress.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- The supplementary files can be downloaded from here.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang LY, Li Q, Yi GP, Cui HL, Liu Y, et al. 2025. Community protection of antibiotic biodegradation modulates microbiome succession and stability. Biocontaminant 1: e019 doi: 10.48130/biocontam-0025-0016

Community protection of antibiotic biodegradation modulates microbiome succession and stability

- Received: 11 October 2025

- Revised: 10 November 2025

- Accepted: 19 November 2025

- Published online: 12 December 2025

Abstract: Antibiotic residues exert persistent and intense stress on environmental microbiomes, thereby impacting community stability. However, the association between the establishment of antibiotic degradation and community succession remains poorly understood, hindering environmental risk assessment of antibiotic disturbance. Here, the role of antibiotic biodegradation is investigated in community protection by comparing two strategies (natural adaptation and pre-adaptation via antibiotic degrader bioaugmentation) under sulfamethoxazole (SMX) stress in sequencing batch reactors. Pre-adapted communities exhibited higher degrader abundance and improved SMX degradation compared to naturally adapted communities. SMX stress retarded succession in naturally adapted communities while maintaining significantly higher species diversity; whereas more efficient biodegradation in pre-adapted communities alleviated antibiotic stress and restored regular community succession. SMX degraders stabilized microbial interactions by maintaining connectivity under stress, with antibiotic stress and degradation capacity jointly shaping microbiome succession. Naturally enriched SMX degraders exhibited average causal mediation effects that were 1.25-fold higher than the total antibiotic effects, whereas bioaugmented communities exhibited diminished antibiotic sensitivity. These findings highlight the critical role of key degraders in protecting communities and maintaining ecosystem stability under antibiotic stress, providing fundamental insights for developing resilience-based strategies to manage antibiotic risks and conserve ecosystems.