-

Drought is generally regarded as a complex periodic climate phenomenon that has significant ramifications for agriculture, water resources, the environment, and human worldwide. Drought is one of the major abiotic stress factors that limit plant growth and development. It obstructs plant respiration and photosynthesis, thus affecting growth, development, and physiological metabolism[1]. Drought has a significant impact on the biosynthesis of plants at different growth stages, resulting in a reduction in dry matter, accelerated abnormal yellowing of leaves, and detrimental effects on ornamental quality. These effects can lead to substantial economic losses[2]. The process of seed germination represents a pivotal phase in the life cycle of a plant, marking the commencement of its growth and development. This stage is of paramount importance because of the subsequent growth of the seedling and the formation of its root system. Additionally, drought stress adversely affects metabolic processes at the cellular level, resulting in the disruption of cell division and elongation as well as the water status of tissues and the retardation of seed germination[3]. Therefore, appropriate treatment strategies are essential to alleviate abiotic stresses during the process of seed germination.

Seed treatment can increase plant resistance by improving defence mechanisms and retaining induction memory and also ensures rapid and uniform germination of seeds, accompanied by a minimal incidence of abnormal seedlings[4,5]. Seed treatment can be used as a solution to overcome the problems of low-level germination and seedling establishment under soil drought conditions. Its main advantages are simplicity, low cost, and the absence of expensive equipment[6]. Common methods for promoting seed germination can include treatment with KNO3, microwaves, and GA3, among others. K+ in KNO3 is an essential nutrient for plant growth and development, and NO3- is one of the nitrogen sources. KNO3 treatment improves the germination indices of yarrow seeds[7] and has also been observed to be beneficial for the restoration of the germination vigour of seeds of Oryza sativa L. seeds[8] and Solanum lycopersicum L.[9] seeds under drought stress. KNO3 treatment can also effectively protect Amygdalus L. plants from abiotic stresses and can be applied as a stress reliever[10]. Microwave treatment provides a nonpolluting, efficient and low-energy consumption seed treatment method, which actively promotes seed germination and plant growth[11,12]. The effects of microwave radiation on Abelmoschus esculentus (L.) Moench (okra) seeds resulted in an increase in their germination indices[13] and on castor and lupin seeds, that have been subjected to analogous treatments[14,15]. Muhammad et al.'s study on spinach indicated that microwaves promote seed germination and reverse the adverse effects produced by abiotic stresses[16]. Microwave can alleviate the adverse effects of drought on wheat seed germination[17,18]. GA3 is a plant hormone that plays a pivotal role in regulating diverse aspects of plant growth and development through a complex biosynthetic pathway. GA3 is able to release seed dormancy in Syagrus coronata seeds and alleviate the damage caused by drought stress to seedlings[19]. Furthermore, GA3 treatment has been demonstrated to increase the emergence of seedlings and the vitality of seeds in species such as Cicer arietinum L. and Cannabis sativa L., even under conditions of drought stress[2].

Irises represent a particularly rewarding genus of garden perennials. They have long been considered fundamental to the success of any flower garden. Iris typhifolia is a perennial herbaceous plant of the Iris L. in the Iridaceae Juss. I. typhifolia has strong stress resistance, shows no signs of aging after growing for many years, and has high ornamental value. It is a valuable ecological restoration material for basic planting in arid regions. I. typhifolia is cultivated extensively in areas of China including Jilin, Inner Mongolia and other regions, in wetlands and grasslands. I. typhifolia is considered to be an excellent garden flower in the northern region of China. The market demand is also increasing, indicating the potential for large-scale popularisation and application, as well as high commercial promotion value[20]. Although Iris L. is drought tolerant, its growth and development are often affected by drought conditions[21]. Elucidating the regulatory mechanism of drought tolerance during the germination period of I. typhifolia could be instrumental in facilitating cultivation and molecular breeding. Consequently, the need to increase the seed germination rate under drought conditions and enhance plant cultivation techniques has become an urgent problem.

In arid regions, ornamental plants are mostly groundcovers and foliage plants with relatively homogeneous landscape effects with poor urban landscape quality. Therefore, research on drought tolerance of ornamental plants holds significant value. In addition to Iris L. other than I. typhifolia are also highly resilient to stress. Iris japonica is also resistant to significant drought stress (up to 63 d) through various physiological responses[22]. Current research on drought tolerance in Iris germanica L. focuses on physiological changes and regulatory processes at the molecular level[23]. I. germanica L. has intense drought resistance and can effectively resist drought stress by retaining water. Several important metabolic pathways were regulated by Iris tectorum Maxim. under drought stress and key genes that may be involved in short-term drought response have been identified[24]. Iris lactea Pall. is a perennial herbaceous plant that is tolerant to salt and drought. The gene expression of I. lactea Pall. under abiotic stress was obtained through transcriptional studies, laying the foundation for further research on response mechanisms[25]. Yang et al. (2018) revealed salt tolerance, Na+ and K+ accumulation, and partial tolerance mechanisms in Iris halophila Pall.[26]. Subsequent studies explored the expression patterns of differentially expressed genes and related molecular regulatory mechanisms under salt stress in I. halophila Pall.[27]. It has been demonstrated that Iris L. plants exhibit unique properties and mechanisms in response to drought and other abiotic stresses. The present study contributes to the existing body of knowledge on the subject of Iris L. through the provision of new insights into the plant's resistance physiology of plants. In addition, this study provides a theoretical basis for the rational selection of ornamental plants and improvement of landscape quality in arid areas. Therefore, it is necessary to further strengthen the comprehensive research on the resistance mechanisms of Iris and promote the application.

In this study, KNO3, microwaves, and GA3 were used for treatment. The optimal treatment programme for the seeds of I. typhifolia was determined based on the specific requirements of its seed germination. This programme has been shown to improve the germination rate, alleviate the impact of drought on seed germination, and enhance stress resistance.

-

Mature seeds of I. typhifolia were harvested from the Ornamental Plant Resource Nursery of Jilin Agricultural University (43.49'1.283″ N, 125.240'33.964″ E). The seeds were subjected to a sterilisation process involving the application of sodium hypochlorite (NaClO, 10%) for a duration of 10 min. Afterwards, the seeds were thoroughly washed with running water for a period of 5 min. Next, they were allowed to air-dry at room temperature. The seeds were then divided into four groups for the experiments: untreated seeds, GA3-treated seeds, KNO3-treated seeds, and microwave-treated seeds (Table 1). After treatment, the seeds were transferred to sterilised and filter paper-lined Petri dishes. A volume of 3 mL distilled water was added to each Petri dish. The Petri dishes were subsequently placed in an artificial climate incubator under the following light conditions: 16 h (light)/8 h (darkness) and 24 h (darkness), a light intensity of 2,600 lx and a temperature of 25/15 °C (alternating between 16 and 8 h) for cultivation for 21 d (chamber: RDN-300B, Yanghui, Ningbo, China). The radicle protruding 1−2 mm from the seed coat was used as the germination standard, observe and record the germination status of the seeds was observed and recorded at 9:00 AM on a daily basis, with the relevant germination indices calculated accordingly.

Table 1. Treatments with different solution concentrations, power levels, and treatment durations.

Number Designation Treatment 1 Control water 2 K1 1.0 g·L−1 KNO3, for 1 d 3 K2 3.0 g·L−1 KNO3, for 1 d 4 K3 5.0 g·L−1 KNO3, for 1 d 5 K4 1.0 g·L−1 KNO3, for 2 d 6 K5 3.0 g·L−1 KNO3, for 2 d 7 K6 5.0 g·L−1 KNO3, for 2 d 8 K7 1.0 g·L−1 KNO3, for 4 d 9 K8 3.0 g·L−1 KNO3, for 4 d 10 K9 5.0 g·L−1 KNO3, for 4 d 11 M1 Microwave 450 W, for 5 s 12 M2 Microwave 450 W, for 10 s 13 M3 Microwave 450 W, for 15 s 14 M4 Microwave 450 W, for 20 s 15 M5 Microwave 700 W, for 5 s 16 M6 Microwave 700 W, for 10 s 17 M7 Microwave 700 W, for 15 s 18 M8 Microwave 700 W, for 20 s 19 G1 0.1 g·L−1 GA3, for 1 d 20 G2 0.2 g·L−1 GA3, for 1 d 21 G3 0.3 g·L−1 GA3, for 1 d 22 G4 0.4 g·L−1 GA3, for 1 d 23 G5 0.5 g·L−1 GA3, for 1 d 24 G6 0.1 g·L−1 GA3, for 2 d 25 G7 0.2 g·L−1 GA3, for 2 d 26 G8 0.3 g·L−1 GA3, for 2 d 27 G9 0.4 g·L−1 GA3, for 2 d 28 G10 0.5 g·L−1 GA3, for 2 d 29 P1 Control followed by 5% PEG-6000 30 P2 Control followed by 10% PEG-6000 31 P3 Control followed by 15% PEG-6000 32 P4 Control followed by 20% PEG-6000 33 PG1 G3 followed by 5% PEG-6000 34 PG2 G3 followed by 10% PEG-6000 35 PG3 G3 followed by 15% PEG-6000 36 PG4 G3 followed by 20% PEG-6000 37 PK1 K4 followed by 5% PEG-6000 38 PK2 K4 followed by 10% PEG-6000 39 PK3 K4 followed by 15% PEG-6000 40 PK4 K4 followed by 20% PEG-6000 41 PMR1 M6 followed by 5% PEG-6000 42 PMR2 M6 followed by 10% PEG-6000 43 PMR3 M6 followed by 15% PEG-6000 44 PMR4 M6 followed by 20% PEG-6000 Drought treatment

-

Following treatment of the three groups, the seeds were germinated under drought conditions simulated by 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% PEG-6000. The experiment involved a design of 15 treatments in total (Table 1). Each group of treatments was replicated five times. The untreated seeds were used as the control group. The lost water was replenished on a daily basis by means of weighing. The filter paper was replaced on a 4 d cycle to ensure the stability of the osmotic potential. The cultivation environment and the germination standard were identical to those previously described.

Data statistics and analysis

-

The data were statistically analysed using SPSS (version 26.0) and Excel (version 2023). This study used Duncan's method for significance analysis, the membership function analysis method for comprehensive analysis, and Origin (version 2024) for the graphical representation of data.

Germination rate (%) = (Number of germinated seeds / Total number of seeds) × 100%

Germination potential (%) = (The number of germinated seeds at the peak of germination / The total number of seeds) × 100%

Germination index (GI) = ∑Gt / Dt

Membership function value: R(Xi) = (Xi − Xmin) / (Xmax − Xmin)

In the formula, Dt represents the number of days of germination, Gt represents the number of germinated seeds per day corresponding to Dt, Xi represents the measured value of the germination index, and Xmin and Xmax represent the minimum and maximum values of a certain index among all treatments, respectively.

-

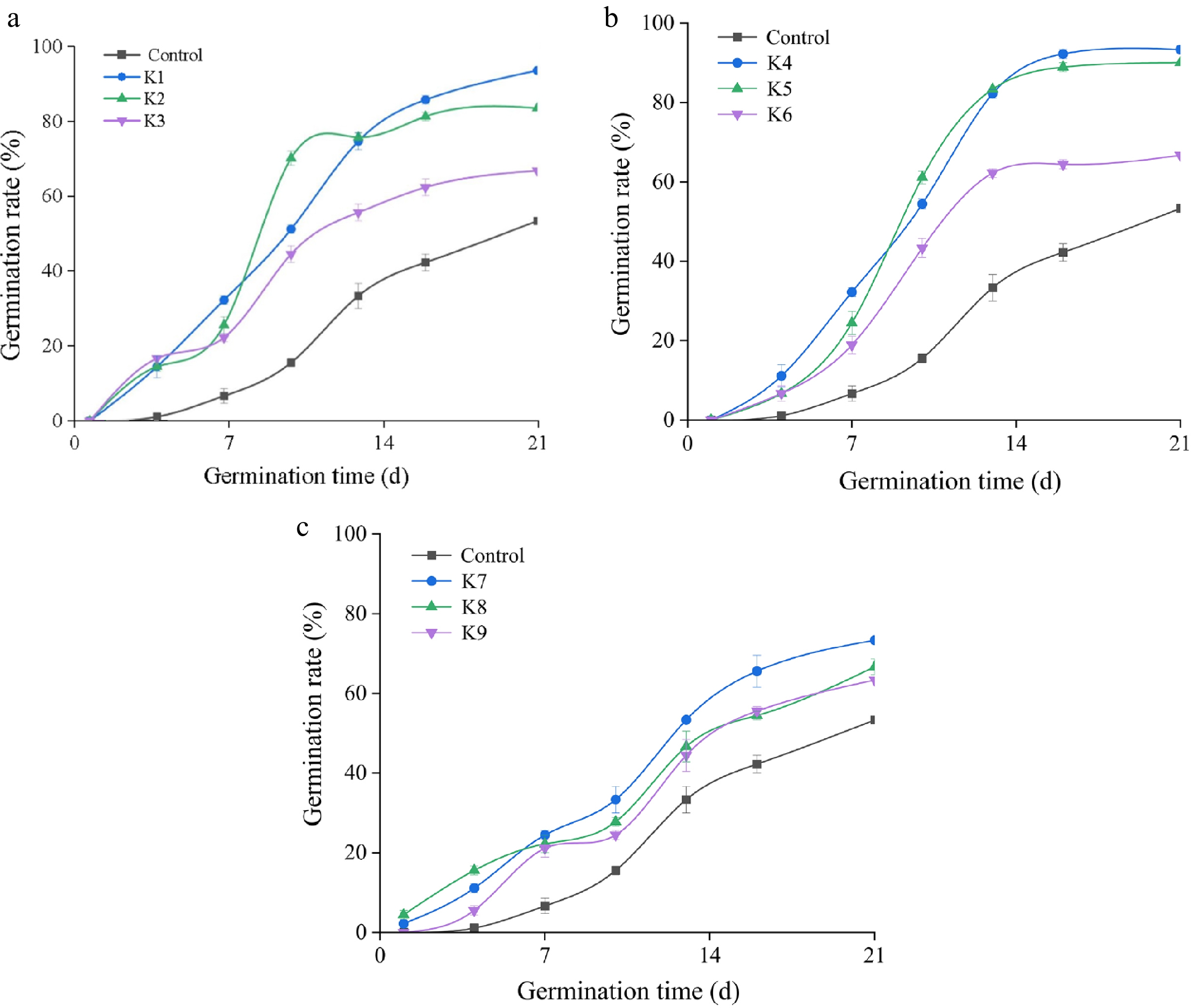

The germination rate of I. typhifolia seeds had been significantly increased after KNO3 solution treatment. Compared with those under the 1 and 2 d treatments, the seed germination dynamics under the 4 d treatment were more consistent, and the average germination time was reduced (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Germination dynamics of I. typhifolia seeds treated with different KNO3 concentrations. (a) Seeds treated with KNO3 solution for 1 d. (b) Seeds treated with KNO3 solution for 2 d. (c) Seeds treated with KNO3 solution for 4 d. Note: Different vertical bar heights ( ± SE) within the same column indicate a significant difference at p < 0.05.

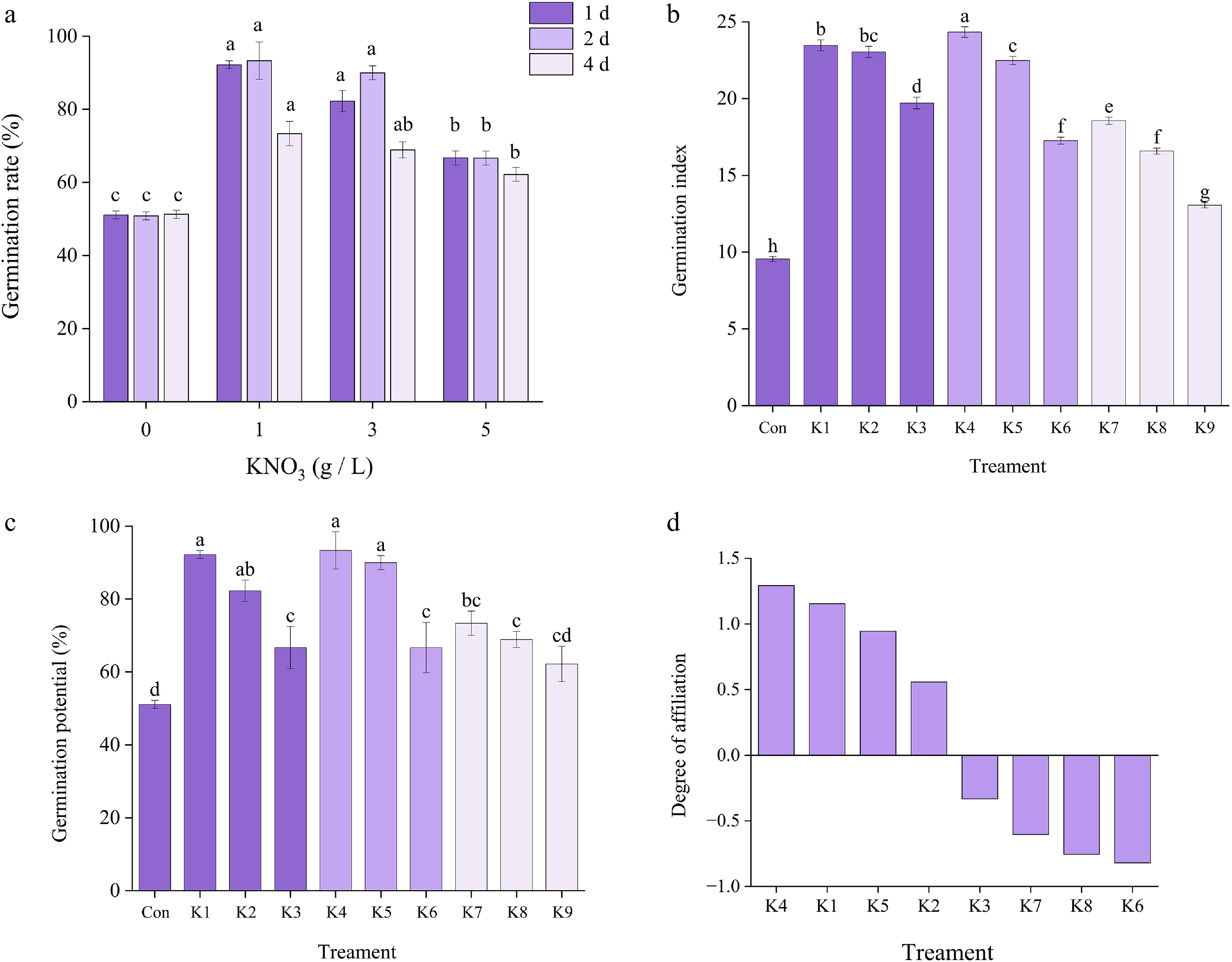

Under normal light and moisture conditions, compared with those in the control group, the germination rate and index of I. typhifolia seeds in the KNO3 treatment group significantly increased (Fig. 2a−c) (p < 0.05). The germination rate and potential reached their maximum values with 2 d of treatment time. Moreover, the highest germination rate was observed in the treatment group that received a solution concentration of 1.0 g·L−1. The findings of this study demonstrated a clear trend of the germination index and the potential for decrease in response to an increase in solution concentration. The values under 1, 2, and 4 d of light and darkness were 93.3%, 92.2%, 86.7%, 81.1%, 73.4%, and 70% respectively. In conclusion, under light conditions, treatment of the seeds with a 1.0 g·L−1 KNO3 solution for 2 d resulted in a significant increase in seed germination.

Figure 2.

Germination indexes of I. typhifolia seeds treated with KNO3 solution for 1, 2, and 4 d. (a) Germination rate. (b) Germination index. (c) Germination potential. (d) Comprehensive analysis of the membership function of seed germination of I. typhifolia seeds after KNO3 treatment. Note: Different letters within the same column indicate a significant difference at p < 0.05 according to ANOVA and Duncan's test.

Comprehensive analysis of the membership function of the seed germination of I. typhifolia seeds after KNO3 treatment

-

A comprehensive evaluation using the membership function was carried out for the three germination indices, namely the germination rate, germination potential and germination index, of I. typhifolia seeds treated with KNO3. The response effects of seed germination to KNO3 were K4 > K1 > K5 > K2 > K3 > K7 > K8 > K6 > K9 (Fig. 2d). Therefore, the KNO3 treatment with the best treatment effect on I. typhifolia seeds was K4. Furthermore, the germination indices of the treated I. typhifolia seeds under light conditions were consistently greater than those under completely dark conditions. Consequently, all subsequent experiments were conducted under light conditions.

Effects of microwave treatment on the germination of I. typhifolia seeds

-

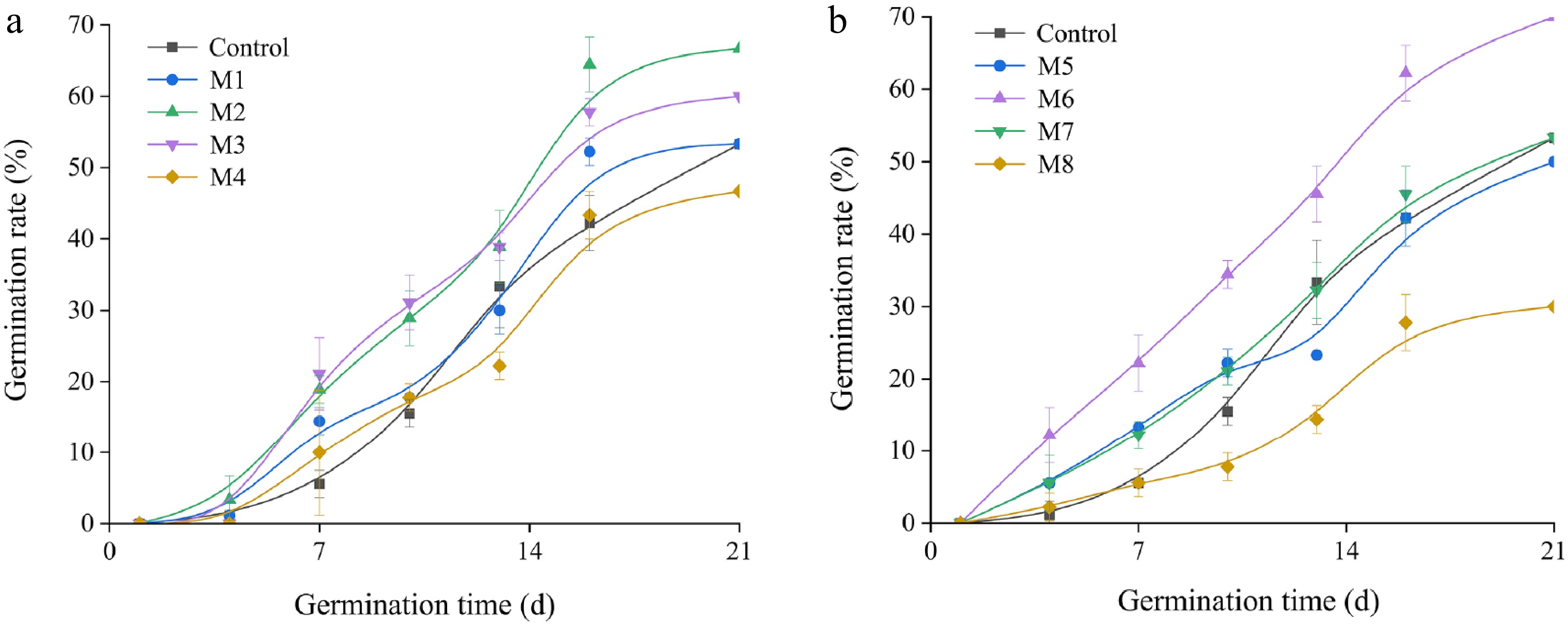

As shown in Fig. 3, the microwave treatment can improved the seed germination rate. Compared with treatment at 700 W, the germination time of the seeds in the treatment at 450 W was greater.

Figure 3.

Germination dynamics of I. typhifolia seeds under microwave treatment. (a) 450 W. (b) 700 W. Different vertical bar heights (± SE) within the same column indicate a significant difference at p < 0.05.

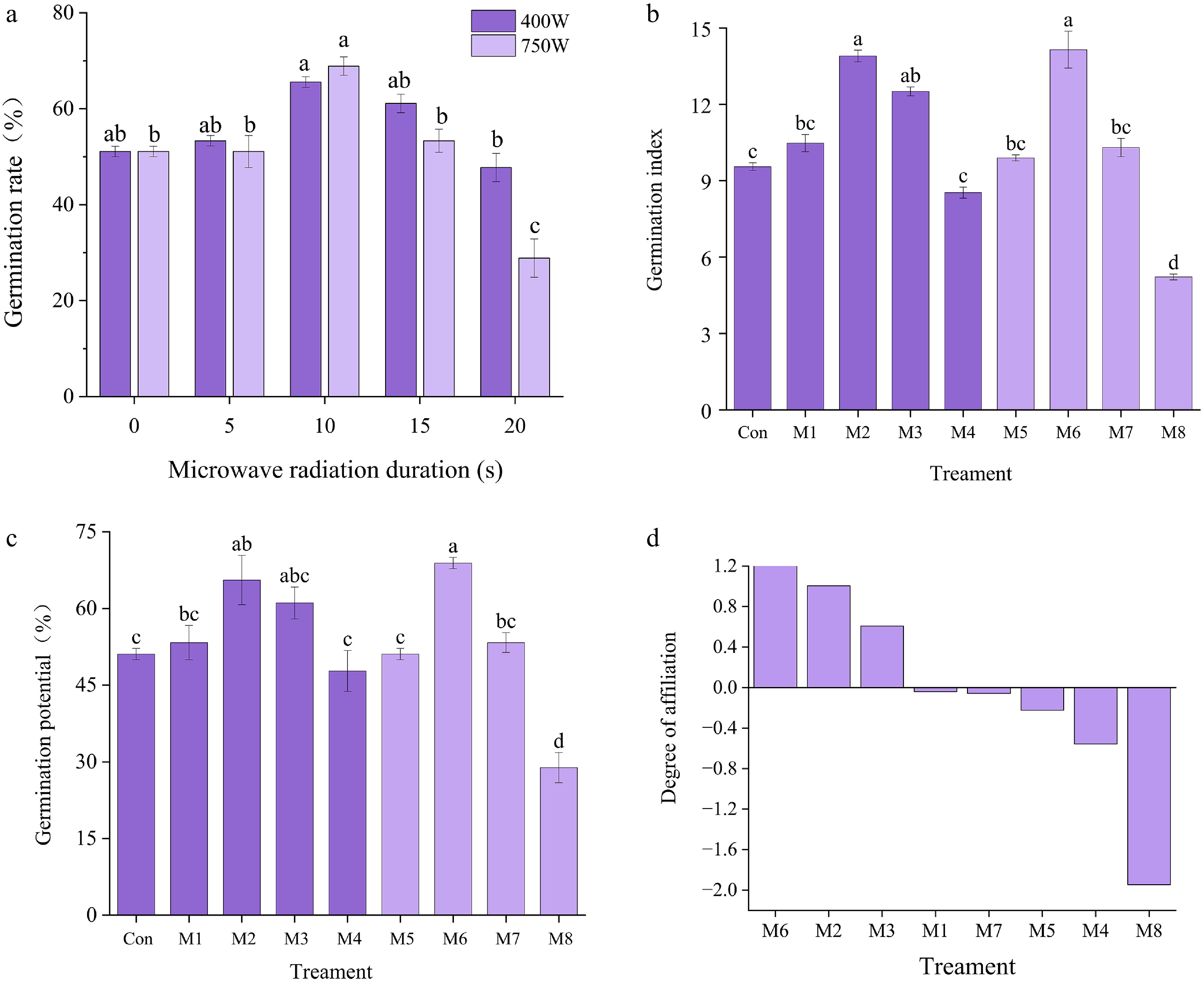

After microwave treatment, the germination index of I. typhifolia seeds first increased, but then decreased with increasing treatment time (Fig. 4a−c). The germination rates peaked at 10 s at 450 W and 700 W (65.6% and 68.9%, respectively). When the treatment time was 20 s, the germination rates decreased to their lowest values (47.8% and 28.9%, respectively). These values were significantly greater than those of the control group (p < 0.05). When treated at a power of 450 W for 5, 10, or 15 s, the seed germination index increased by 9.97%, 45.86%, and 31.27% respectively. When treated for 20 s, it decreased by 10.5%. The inhibitory effect of the treatment at a power of 700 W was more significant than that of the control group. In summary, the promoting effect of microwave treatment on seed germination is proportional to the treatment duration and power. Excessively protracted treatment duration or elevated power levels can clearly impede the efficacy of microwave treatment in promoting seed germination. The degree of inhibition is positively correlated with the radiation intensity.

Figure 4.

Germination indexes of I. typhifolia seeds under microwave treatment for 450 W and 700 W. (a) Germination rate. (b) Germination index. (c) Germination potential. (d) Comprehensive analysis of the membership function of seed germination of I. typhifolia seeds after microwave treatment. Note: The results are means of three replicates (n = 3) ± standard error. Different letters within the same column indicate a significant difference at p < 0.05 according to ANOVA and Duncan's test.

Comprehensive analysis of the membership function of I. Typhifolia seed germination after microwave treatment

-

A thorough evaluation was conducted utilising membership function was carried out for the three germination indices, namely the germination rate, germination potential and germination index, of I. typhifolia seeds following microwave treatment. The response effects of seed germination to microwaves were M6 > M2 > M3 > M1 > M7 > M5 > M4 > M8 (Fig. 4d). Therefore, the microwave treatment with the best treatment effect on I. typhifolia seeds was M6.

Effects of GA3 treatment on seed germination

-

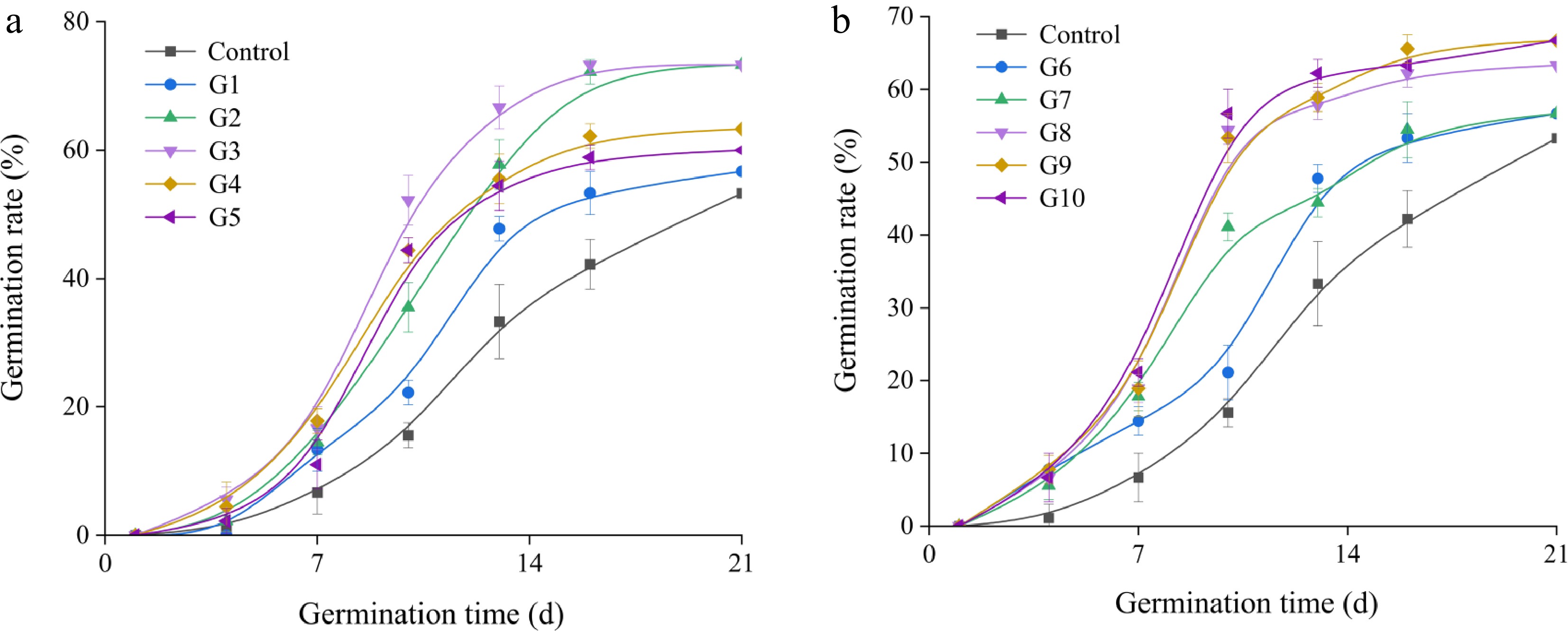

Treatment with GA3 can reduce the time required for I. typhifolia seeds to germinate (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Germination dynamics of I. typhifolia seeds under GA3 treatment for (a) 1 d, and (b) 2 d. Different vertical bars height ( ± SE) within the same column indicate a significant difference at p < 0.05.

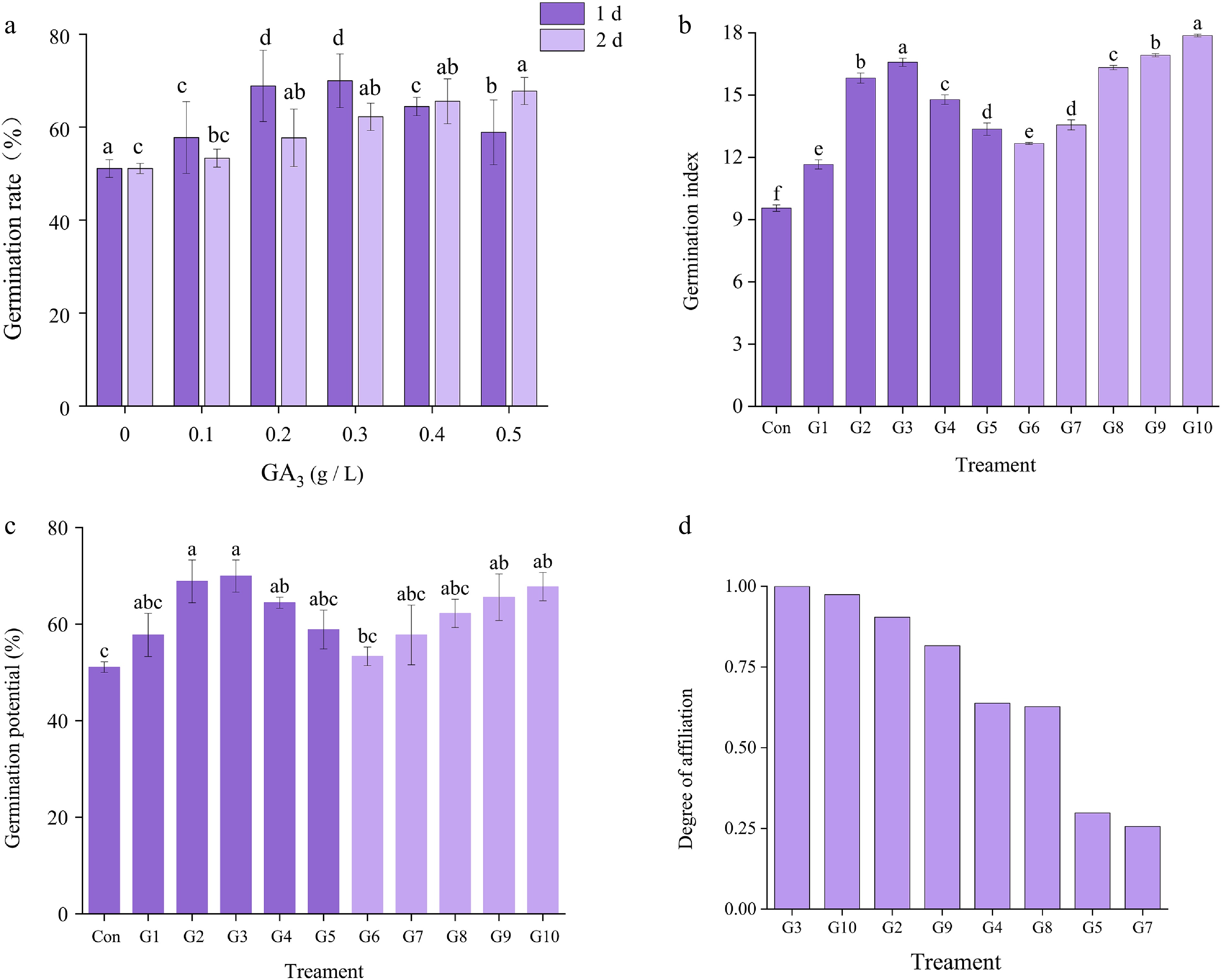

After treatment with GA3 for 1 d, the germination rate of I. typhifolia seeds increased sharply with the increasing of the GA3 concentration (Fig. 6a). The promoting effect was the strongest (69.97%) when the concentration was 0.3 g·L−1, after which promoting effect decreased. As the treatment time increased from 1 to 2 d and as the concentration increased, the germination rate tended to increase. The maximum value of 67.77% was attained at a concentration of 0.5 g·L−1. Compared with the control group, all the treatment groups except the 0.1 g·L−1 showed significant improvement compared to the control group (p < 0.05). When the treatment time was 1 d, the seed germination index and germination potential of I. typhifolia seeds tended to increase in response to increasing solution concentration. The maximum value occurred at a concentration of 0.3 g·L−1, after which a decrease was observed (Fig. 6b, c). As the treatment time increased to 2 d, the germination index and the germination potential tended to increase. The maximum value attained was 67.8% at a concentration of 0.5 g·L−1 (p < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Germination indexes of I. typhifolia seeds under GA3 treatment for 1 and 2 d. (a) Germination rate. (b) Germination index. (c) Germination potential. (d) Comprehensive analysis of the membership function of seed germination of I. typhifolia seeds after GA3 treatment. Note: The results are means of three replicates (n = 3) ± standard error. Different letters within the same column indicate a significant difference at p < 0.05 according to ANOVA and Duncan's test.

Comprehensive analysis of the membership function of I. typhifolia seed germination after GA3 treatment

-

A comprehensive evaluation was conducted utilising the membership function for the three germination indices, namely, the germination rate, germination potential and germination index, of I. typhifolia seeds following GA3 treatment. The response effects of seed germination to GA3 were G3 > G10 > G2 > G9 > G4 > G8 > G5 > G7 > G1 > G6 (Fig. 6d). Therefore, GA3 treatment with the best treatment effect on I. typhifolia seeds was G3.

Effects of different treatments on the germination characteristics of I. typhifolia seeds under drought stress

-

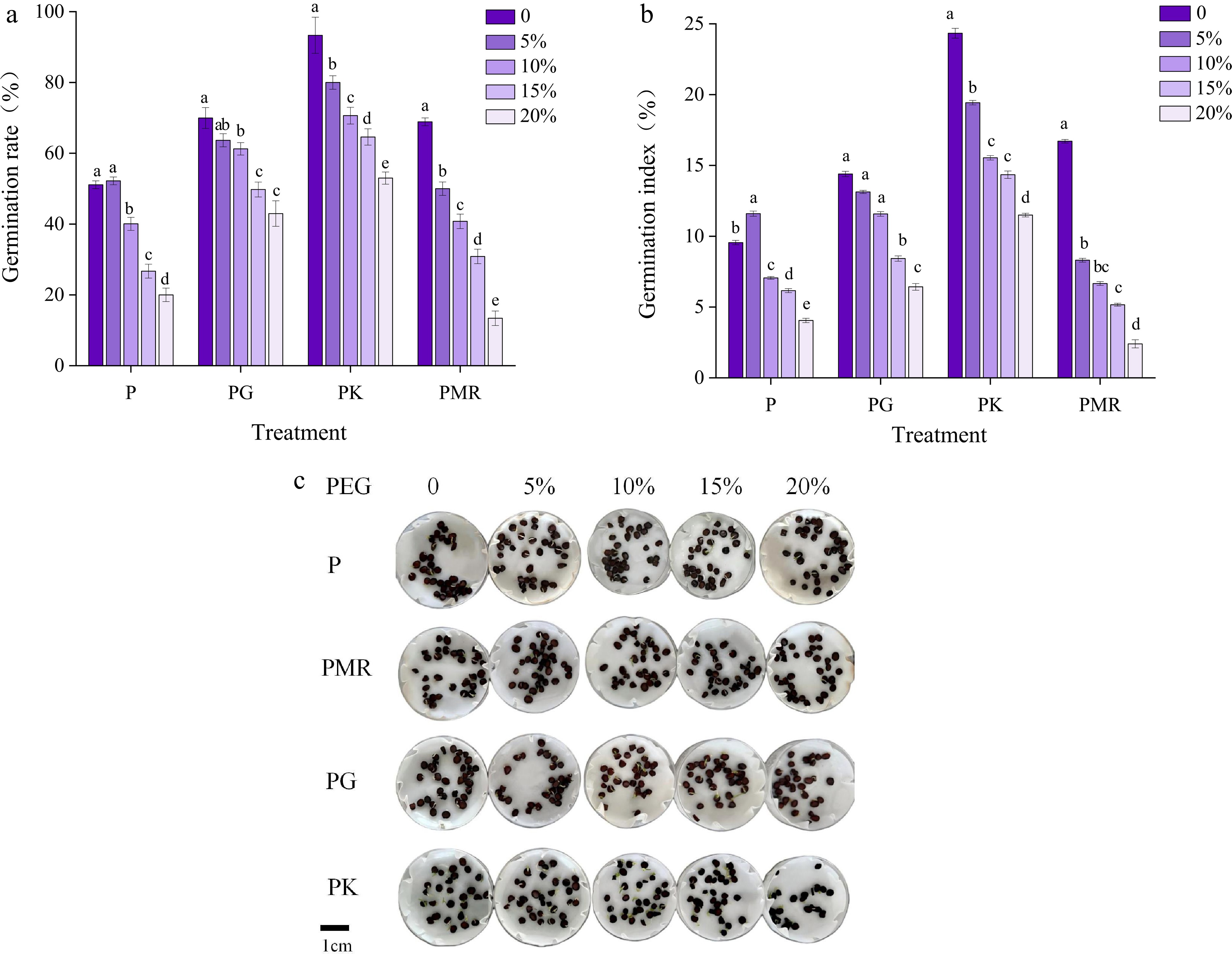

The application of 5% PEG-6000 to induce mild drought conditions resulted in the promotion of seed germination, with an observed germination rate of 52.2% (Fig. 7a, b). Under the treatments with 10%, 15%, and 20% PEG-6000, the germination rates of the seeds were 40.07%, 26.7%, and 20% respectively. In comparison with those of the control group, the germination rate and index of the seeds subjected to treatment with 20% PEG-6000 were significantly lower, with decreases of 60.78% and 57.9%, respectively. Compared with those in group P, the germination rates of I. typhifolia seeds subjected to treatment with KNO3 under drought stress at various concentrations increased. Specifically, the KNO3-treated groups exhibited 53.8%, 75.0%, 141.0%, and 165.0% increases in the germination rate, with corresponding increases in the germination index elevations of 67.2%, 118%, 130.6% and 180.5% respectively. For the seeds in the PG treatment group, the germination rates increased by 23.1%, 52.2%, 81.5%, and 110%, and the germination index increased by 12.9%, 63.4%, 35.5%, and 56.1%, respectively. After microwave treatment, there was no obvious promoting effect in the treatment groups of PMR1, PMR2, and PMR3 treatment groups compared with the P group. The PMR4 treatment group showed an inhibitory effect under high-concentration drought stress. In summary, the application of KNO3 and GA3 significantly mitigated the inhibitory effect of drought stress on I. typhifolia seed germination. Compared with GA3 treatment, KNO3 treatment is more efficacious at facilitating seed germination under drought stress in comparison with GA3 treatment.

Figure 7.

Alleviation effects of different treatments on the germination of I. typhifolia seeds under drought stress. (a) Germination rate. (b) Germination index. (c) Status of seeds germinated under drought stress for 21 d after different treatments. Note: The results are means of three replicates (n = 3) ± standard error. Different letters within the same column indicate a significant difference at p < 0.05 according to ANOVA and Duncan's test.

-

Chemical treatment is advantageous for improving the speed, efficiency, and control of seed germination[28]. The judicious selection and application of appropriate chemicals is of paramount importance. In this study, the germination rate and germination index of I. typhifolia seeds subjected to KNO3 treatment were found to be considerably greater than those of the control group. KNO3 treatment also promotes the germination of seeds of Oriental Lily[29], Eremurus spectabilis[30], and sweet granadilla[31]. This may be due to the positive roles played by both K+ and N+ in enhancing the membrane stability[32,33] and in promoting the initiation of the internal metabolic processes in seeds[34]. K+ and N+ have been demonstrated to reduce the cell osmotic potential by altering water absorption, thereby stabilising the water absorption of cells[35], and shortening the germination time without affecting uniformity or synchronicity[36−39]. However, the efficacy of KNO3 is contingent upon factors such as on the plant species, the concentration of the solution, and the duration of the treatment. Extending the treatment time to more than 2 d will reduce the germination-promoting effect of KNO3[40], which was also confirmed in the present study. The germination indexes decreased when the treatment duration was 4 d. However, the most effective treatment duration for promoting the germination of I. typhifolia seeds was observed to be 2 d.

The study of the accelerated germination of I. typhifolia seeds after microwave treatment indicated that microwave treatment has a positive impact on seed germination under certain treatment conditions. Similar results were obtained in studies on Solanum melongena L. seeds[41]. Microwave treatment under appropriate power and treatment duration can increase the seed germination rate. However, it should be noted that excessive power and extended treatment times can impede seed germination. There is clearly a discrepancy in the tolerance ranges exhibited by diverse plant species with respect to microwave radiation. In comparison with the results of a germination study of Daucus carota L. seeds under microwave treatment conducted by Dorota et al., it can also be concluded that I. typhifolia seeds demonstrate a reduced tolerance range to microwave radiation in comparison with carrot seeds[42]. The increase in the germination rate after microwave treatment may be related to the accelerated activation of metabolic enzyme activity and alterations in the internal component structure after microwave treatment[43]. However, microwave treatment for an extended duration and at elevated power levels can result in the inactivation of enzymes within the seeds[44], thereby reducing the germination rate.

The results of this study indicate that the treatment with GA3 promotes the germination of I. typhifolia seeds. GA3 also significantly affects has a significant impact on the germination rates of plants such as Mini-watermelon[45], and Penstemon digitalis cv. Husker Red.[46], Tamarindus indica L.[47], and Elaeocarpus prunifolius Wall. Ex Müll. Berol.[48]. This may be because GA3 promotes seed germination by enhancing growth-hormone synthesis, increasing the content of endogenous cytokinins, increasing enzyme activity within the seeds, and accelerating the metabolic processes[49,50]. Mahak Rani further clarified the mode of action of GA3 in the study of Carica papaya L. 'Red Lady'[51]. Treatment with GA3 has an inflection point. When the concentration of GA3 is lower than this point, the germination rate of the seeds increases with the increasing concentration. However, when the concentration exceeds this inflection point, the germination rate decreases as the concentration increases[51]. A similar trend is evident in this experiment. When the seeds were treated with GA3 for 1 d, all the germination indices peaked values at a concentration of 0.3 g·L−1. After this concentration was exceeded, these indices tended to decrease as the concentration increased. This phenomenon may be due to anaerobic fermentation caused by the high concentration of the solution soaking. This results in the production of acid within the seed, thereby hindering the process of germination.

Effects of different treatments on the germination of I. typhifolia seeds under drought stress

-

In order to combat damage to plants from various adverse living environments, such as drought, plants have evolved a series of complex defence response mechanisms over a long period of evolution. The findings of this study show that the treatment with 5% PEG-6000 can increase the process of I. typhifolia seeds. Conversely, the germination rate of the seeds substantially decreased at concentrations of 15% and 20%. This may be attributed to the stimulation of self-protective mechanisms in seeds, triggered by the presence of a low concentration of PEG-6000 solution. The seeds can regulate the internal moisture content and prevent water absorption expansion, thereby preventing damage to the membrane[52]. When the stress exceeds a certain concentration, it breaks through the self-protection mechanism of the seeds. Osmotic adjustment substances are no longer capable of regulating the internal water balance of the seeds. This can result in a severe shortage of water, which leads to the seeds being unable to absorb sufficient water immediately. Consequently, the vitality of the seeds decreased, and their germination was impeded[4].

Duermeyer et al. reported that KNO3 treatment affects the antioxidant metabolism of plant seeds and promotes the accumulation of antioxidants. KNO3 helps to counteract the generation of reactive oxygen species and improve the stress resistance of seeds[53]. For instance, a study by Kaya et al. demonstrated that the application of KNO3 can increase the germination of Helianthus annuus L. seeds under conditions of drought stress[5]. The results of the present study similarly corroborated the finding that KNO3 treatment alleviated the germination of I. typhifolia seeds under drought stress, and the effect became more significant with increasing the stress levels.

In this study, the seed germination rate of I. typhifolia increased under PG treatment, which effectively alleviated the effects of drought injury on seed germination. These results are consistent with the conclusions of previous studies. In a research on industrial Cannabis sativa L. seeds, revealed that treatment with GA3 can increase the drought tolerance of Cannabis sativa L. seeds[2]. Therefore, soaking seeds with an appropriate concentration of GA3 can also significantly increase the germination rates of seeds such as Ammopiptanthus mongolicus, Linum usitatissimum L., Sesamum indicum L., Allium cepa L., and Cucumis melo L. under drought stress[54,55]. As a pivotal plant hormone that regulates plant growth, development, and stress resistance, GA3 plays a pivotal role in mitigating the impact of abiotic stress on plants[56]. This may be attributable to the capacity of GA3 to curtail the minimum effective contact time of various germination inhibitors or to stimulate the enzyme activity within the seeds, therebyincreasing the germination index.

Some scholars have hypothesised that microwave treatment can significantly inhibit the infection of pathogenic bacteria during the seed germination period, reduce the germination time, and increase the germination rate[57]. However, the results of this study demonstrate that the alleviating effect of microwave treatment on the seeds of I. typhifolia under drought stress is not evident. Furthermore, when the seeds are subjected to high-concentration drought stress, the inhibitory effect of microwave treatment on seed germination intensifies. This discrepancy may be attributed to the varying degrees of sensitivity exhibited by different plant species to microwave treatment.

-

Following treatment with KNO3, GA3, and microwaves, the seed germination index of I. typhifolia increased, with a reduction in germination time and an increase in germination rate. The seeds of I. typhifolia exhibited optimal germination parameters after treatment with 1.0 g·L−1 KNO3 solution for 2 d. Furthermore, the application of KNO3 and GA3 treatments resulted in a positive regulatory effect on the seed germination of I. typhifolia under drought stress. An increase in the concentration of PEG above 10% resulted in a substantial inhibition of germination. KNO3 was found to be the most efficacious at reducing this effect. Under drought stress with 20% PEG, the application of KNO3 increased the germination rate of I. typhifolia seeds from 20% to 53%, representing a 165% increase.

Treatments with KNO3 and GA3 can improve the drought resistance of I. typhifolia seeds to promote their use in landscaping. KNO3 and GA3 are commonly used chemical reagents that are inexpensive, stable, and readily available. The effective pretreatment solution obtained in this study can be mechanically coated onto the seed surface as a seed coating agent, or the seeds can be dipped in the solution before sowing or sprayed after sowing, thus achieving precise, efficient, and automated large-scale treatment. Furthermore, it can also be amalgamated with other technical measures, such as the incorporation of water-retaining agents or covering with plastic film. This study will also optimise irrigation schemes for natural seeding of I. typhifolia to reduce labour costs and economic and resource losses during cultivation and production. The provision of a theoretical basis and technical support for the breeding of more resistant ornamental plant varieties in the future is highly important.

This paper was sponsored by The Key Research and Development Project of Changchun Science and Technology Bureau (Grant No. 21ZGN08), and Jilin Province College Student Innovation Training Program (Grant No. 202510193089).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Chen L, Sun Y, Lu X, Yu J; analysis and interpretation of results: Yu J, Cao Q, Zhao M, Yuan Y, Wang X, Wang S; draft manuscript preparation: Chen L, Sun Y, Lu X, Yu J, Wang Q, Wu S; All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Yu J, Cao Q, Wang X, Wu S, Zhao M, et al. 2025. Enhancing seed germination and drought stress resistance in Iris typhifolia Kitag. through pretreatment techniques. Technology in Horticulture 5: e041 doi: 10.48130/tihort-0025-0037

Enhancing seed germination and drought stress resistance in Iris typhifolia Kitag. through pretreatment techniques

- Received: 02 April 2025

- Revised: 05 September 2025

- Accepted: 15 September 2025

- Published online: 17 December 2025

Abstract: Drought stress severely limits seed propagation in Iris. This study aimed to improve the seed germination of Iris typhifolia Kitag. and mitigate the effects of drought stress on seed germination. The mitigating effects of potassium nitrate (KNO3) solution dipping, microwave irradiation, and gibberellin (GA3) treatment on seed germination under polyethylene glycol (PEG) to simulate drought conditions were systematically evaluated. The results showed that all three treatments significantly improved seed germination rate, germination index, and germination potential. In terms of mitigating the drought stress inhibition on seed germination, dipping the seeds in KNO3 solution was the most effective treatment. The optimum treatment for KNO3 was 2 d of dipping at a concentration of 1.0 g·L−1. Compared with the control treatment, the KNO3 treatment increased the germination rate of I. typhifolia seeds by 165% under 20% PEG-simulated drought stress conditions. These findings provide important insights for the development of effective seed treatment programs and water management strategies, and provide technical support for the application of I. typhifolia in drought areas.

-

Key words:

- Iris typhifolia Kitag. /

- Seed germination /

- Drought stress /

- KNO3 /

- GA3 /

- Microwave irradiation