-

The environmental spread, clinical prevalence, and global burden of multidrug-resistant bacteria or "superbugs" have necessitated comprehensive surveillance and mitigation of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), the ability of microorganisms to survive and proliferate under inhibitory or lethal concentrations of antibiotics[1]. Since the large-scale use of antibiotics in the 1940s, these compounds have revolutionized modern medicine but have also inevitably driven the emergence and dissemination of resistant strains. The World Health Organization (WHO) has recognized AMR as one of the most severe global public health threats of the 21st century[2]. According to the O'Neill Report, AMR could cause an accumulated economic loss of up to USD

${\$} $ Global concern over AMR has now extended beyond clinical boundaries to encompass critical environmental dimensions. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) has emphasized that reducing environmental pollution is critical to slowing the spread of antimicrobial resistance[5]. In 2006, Pruden et al. first conceptualized antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) as emerging environmental contaminants, underscoring that AMR should be treated not only as a medical issue but also as an environmental one[6]. Since then, extensive research has demonstrated that resistance genes and resistant bacteria circulate widely across natural and engineered ecosystems, linking environmental contamination with public health risks through complex transmission pathways. AMR is not solely a product of human activity. Evidence suggests that resistance genes and resistant bacteria existed in the natural environment long before the discovery and clinical application of antibiotics[3]. Soil bacteria and fungi naturally produce many antimicrobial molecules, including antibiotics, and these producers possess self-resistance genes to prevent autotoxicity[7]. Nevertheless, the overuse of antibiotics in medicine, animal husbandry, and agriculture, coupled with environmental pollution from wastewater discharge, improper waste treatment, and other anthropogenic activities, has dramatically accelerated the accumulation and spread of AMR in the environment[8,9]. Consequently, the environment functions as both a reservoir and a conduit of resistance, posing threats to human, animal, and ecosystem health.

Bacterial resistance can be categorized into intrinsic and acquired resistance depending on the origin and mechanisms. Intrinsic resistance is chromosomally encoded and reflects inherent structural or functional traits, such as low membrane permeability or constitutive efflux pumps, which are inherited through vertical gene transfer (VGT)[10]. Acquired resistance is primarily acquired via horizontal gene transfer (HGT), mediated by mobile genetic elements such as plasmids, integrons, and transposons[11]. In environmental settings, resistant bacteria and resistance genes originate from both indigenous microbial communities and anthropogenic sources. Effluents from urban wastewater treatment systems, livestock production facilities, and pharmaceutical manufacturing operations typically contain elevated concentrations of both chemical and microbiological contaminants. These waste streams are increasingly recognized as significant sources of the dissemination of AMR and therefore warrant priority attention in surveillance and control efforts[1,12].

Guided by the WHO's Global Action Plan, combating AMR relies on comprehensive surveillance and effective mitigation measures[13]. Unlike the well-established surveillance methods in clinical and veterinary settings, where antibiotic susceptibility testing (AST) informs appropriate antibiotic selection, environmental AMR surveillance focuses primarily on characterizing the resistome's traits, specifically the types, abundance, mobility, and host associations of ARGs, through integrated detection of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) and ARGs[1,14]. With advances in molecular biology and metagenomics, detection and monitoring of AMR in the environment have expanded from traditional phenotype-based culture methods to include polymerase chain reaction (PCR), quantitative PCR (qPCR), metagenomic sequencing, and novel assays based on clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)–CRISPR-associated (Cas)[15−17]. Meanwhile, global efforts to control AMR have emerged, including the One Health framework, which integrates the human, animal, and environmental dimensions, alongside interventions such as source reduction and process controls in wastewater treatment and pollution remediation.

In this review, we systematically synthesize the current knowledge on the sources, surveillance, and mitigation of environmental AMR within the One Health framework. Although whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and bioinformatics have been extensively applied in clinical AMR surveillance and outbreak investigation[18], environmental resistomes present fundamentally different challenges. Distinguishing itself from existing literature that primarily focuses on clinical genomic surveillance[18], transmission dynamics in specific contexts[19], or general environmental roles in the evolution of resistance[1], this work advances the field through several key contributions. First, we provide a comprehensive integration of environmental resistomes within the One Health framework, with particular emphasis on critical traits, including ARGs' mobility (governing HGT), host pathogenicity (determining clinical relevance), and multi-resistance patterns (constraining therapeutic options), which collectively determine the health risks across the environmental, animal, and human domains. Second, we systematically compare phenotypic and genotypic surveillance approaches, highlighting their complementary strengths and the necessity of methodological integration for comprehensive characterization of the resistome in complex environmental matrices. Third, we critically examine both source control and process control mitigation strategies, emphasizing the need for standardized protocols that enable comparable global surveillance data. Finally, we offer forward-looking perspectives on emerging technologies and integrated analytical frameworks that may be essential for enhancing our capacity for AMR surveillance and developing evidence-based control policies in the post-pandemic era. By bridging fundamental mechanisms with practical applications, this synthesis aims to assist researchers, policymakers, and public health professionals in developing evidence-based strategies for combating the growing threat of environmental AMR (Fig. 1).

-

Antimicrobial resistance is generally classified into two forms: intrinsic resistance, which is an inherent trait encoded within the bacterial chromosome, and acquired resistance, which arises in previously susceptible bacteria through genetic adaptation. A comprehensive understanding of both forms is essential to elucidate the complexity and global scale of the AMR crisis.

Intrinsic resistance

-

Intrinsic resistance refers to the innate ability of a microorganism to withstand an antibiotic, a characteristic encoded in its chromosomal DNA and shaped by millions of years of evolution[20]. These natural resistance mechanisms predate the clinical use of antibiotics. For example, the β-lactamase gene, a common antibiotic resistance determinant, has an evolutionary history of approximately two billion years, long before humans discovered β-lactam antibiotics[21]. In their natural habitats, these genes often play roles in microbial signaling or metabolic detoxification, especially at antibiotic concentrations far below clinical levels, thereby enhancing microbial fitness. The ancient origins of AMR are further confirmed by paleogenomics. Analysis of 30,000-year-old DNA from permafrost revealed a diverse array of resistance genes, including those for β-lactams, tetracyclines, and glycopeptides, with the ancient vancomycin resistance protein showing high structural similarity to modern variants[22]. Similarly, bacteria isolated from remote, human-free caves have been found to carry macrolide kinases and exhibit resistance to multiple antibiotics, including semisynthetic drugs, reinforcing the notion that AMR is an ancient and widespread natural phenomenon[23].

Acquired resistance

-

In contrast to intrinsic resistance, which predates antibiotic exposure, acquired resistance emerges when previously susceptible bacteria obtain new genetic determinants that confer reduced susceptibility. This occurs primarily through HGT, which is mediated by plasmids, transposons, and integrons, or through spontaneous chromosomal mutations that modify antibiotic targets. Human activities have greatly accelerated the spread of acquired resistance, establishing extensive environmental reservoirs that facilitate rapid gene exchange among diverse bacterial communities.

The large-scale production and use of antibiotics exert intense selective pressure, favoring the emergence of resistant strains[24]. A substantial fraction of antibiotics administered to humans and animals is excreted unmetabolized, enriching ARGs in the host microbiota and subsequently introducing both antibiotic residues and resistant bacteria into the environment via waste streams[25,26]. These inputs drive the amplification and dissemination of resistance genes across environmental compartments. Beyond direct antibiotic selection, recent large-scale genomic studies reveal that the evolution of AMR is also shaped by broader anthropogenic and environmental conditions, including agricultural practices, rural development, climate change, urbanization, and socioeconomic factors. For example, global analyses of Salmonella populations show that antibiotic consumption in humans and animals, together with these contextual drivers, jointly influence regional and global patterns of AMR's spread[27,28].

Key reservoirs of environmental AMR

-

Environmental systems impacted by antibiotics and resistant bacteria often become key reservoirs where selection, microbial interactions, and HGT amplify AMR. Among these reservoirs, wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), livestock production environments, and pharmaceutical manufacturing effluents play crucial roles in sustaining and disseminating resistance across ecosystems.

Hospital and urban WWTPs

-

Wastewater treatment plants are critical hotspots where ARGs from medical and domestic sources converge[29]. Hospital effluents are among the most significant and concentrated upstream contributors to WWTPs, carrying high concentrations of antimicrobial residues, resistant pathogens, and mobile genetic elements[30]. A recent large-scale analysis of 166 hospital effluents in Shanghai confirmed the prevalence of high-risk ARGs and plasmid-borne resistance genes in pathogenic bacteria, underscoring the role of hospital wastewater as a key reservoir for clinically relevant determinants of resistance[31]. These wastewater streams, originating from clinical and residential sources, are reservoirs laden with antibiotic-resistant bacteria and ARGs[32].

Conventional treatment processes are often ineffective at eliminating these contaminants, allowing resistant bacteria and ARGs to persist throughout the treatment chain. The study by Ju et al. showed that ARGs remain actively expressed from the influent to the sludge and effluent stages, with ongoing gene exchange between environmental bacteria and human pathogens[33]. WWTPs disseminate AMR through two primary pathways: effluent discharge, which can increase ARGs' abundance in receiving rivers by one or two orders of magnitude[34], and the land application of biosolids (sludge). Notably, sludge composting may, in some cases, increase the abundance of certain ARGs rather than reduce it, thereby elevating the risk of soil contamination and the propagation of environmental resistance[35].

Livestock and aquaculture

-

The livestock industry is a primary contributor to environmental AMR. Globally, about 70% of antibiotics are used in food animals, leading to the enrichment of ARGs in animals' gut microbiota and manure[36]. The application of manure as fertilizer represents the main route through which these animal-derived ARGs are introduced into agricultural soil. Recent metagenomic analyses revealed that this practice introduces a complex cocktail of biological risks. For instance, a comprehensive study detected 157 potential human bacterial pathogens in manure-amended soils, where they co-occurred with abundant virulence factor genes and diverse ARGs, with pig manure identified as posing the highest microbiological risk[37].

Similarly, in aquaculture systems, antibiotic misuse drives the proliferation and dissemination of resistance. A large-scale investigation of mariculture environments in China identified 262 distinct ARGs, many of which were classified as high-risk, and crucially linked them to 25 genera of zoonotic pathogens, such as Vibrio, which serve as potential reservoirs and vectors for the environmental persistence and spread of these determinants of resistance[38].

Pharmaceutical manufacturing effluents

-

Waste from antibiotic production facilities is another primary source of high concentrations of environmental AMR. An investigation of a spiramycin production plant revealed that the abundance of macrolide resistance genes in its activated sludge was over 100 times higher than that in municipal WWTP sludge. These resistance genes were frequently linked to integrons and other mobile genetic elements that facilitate HGT, underscoring the elevated risk of dissemination from these industrial sources[39].

Further supporting this, Qiao et al.[40] demonstrated that wastewater discharged from a sulfonamide-producing plant substantially increased both the abundance and diversity of ARGs in the receiving soils and riverine environments. Resistome levels in surface waters and sediments exceeded global medians, and the soils exhibited substantial enrichment in total and sulfonamide ARGs. The detection of high-risk ARGs and multidrug-resistant pathogens highlighted the significant ecological impacts of pharmaceutical wastewater and its key role in shaping downstream environmental resistomes.

-

Within the One Health framework, environmental surveillance of AMR represents a critical pillar for understanding the dynamics of resistance across human, animal, and environmental interfaces. As emerging global contaminants, ARB and ARGs exhibit widespread prevalence across nearly all habitats, including soil, water, and air[19]. Unlike abiotic chemical pollutants, ARGs are mobile and can replicate within viable bacterial hosts, complicating efforts to monitor both the current burden and the ongoing evolution of AMR. Environmental AMR surveillance aims to characterize the traits of resistomes (basic traits such as the types, abundance, and distribution of ARGs; key traits such as the mobility of resistance, host pathogenicity, and multi-resistance), thereby providing essential evidence for health risk assessments. This characterization can be achieved through integrated detection of ARB and ARGs using two complementary approaches: Phenotypic characterization of ARB and genotypic profiling of ARGs[33]. When focusing on ARGs, identifying their bacterial hosts and analyzing their functional characteristics constitute the critical next steps. Beyond cataloging the types of ARGs and quantifying their abundance, surveillance must prioritize the key traits. This trait-based framework, as proposed and practiced by Ju and collaborators[33,41], facilitates targeted risk assessment and informs mitigation strategies to block ARGs' transmission within and across engineered compartments and natural habitats. Although both phenotypic and genotypic approaches are indispensable for detecting ARB and profiling resistome traits, each faces inherent limitations when applied to complex environmental matrices (Fig. 2). Integrating these approaches into combined analytical workflows significantly enhances targeted surveillance of clinically and environmentally relevant ARB and enables comprehensive profiling of critical resistome traits that pose risks across the complete extent of One Health[41,42].

Phenotypic methods

Culture-based methods

-

Classic culture-based methods are widely used for AMR surveillance by isolating and analyzing target bacteria from complex samples[15]. On the one hand, the number of cultivable ARB can be directly counted by phenotypic screening using antibiotic-amended selective agar plates. On the other hand, isolated bacterial strains of significant clinical concern, such as Escherichia coli[43], Enterococci[15], and Aeromonas spp.[44], can be further analyzed regarding their phenotypic characteristics, indicating resistance to the tested antibiotic stress (e.g., metabolic ability, optimal growth conditions, motility, and environmental tolerance). In environmental applications, culture-based approaches have been extensively deployed for monitoring ARB in WWTPs, surface waters, agricultural soils, and hospital effluents, enabling comprehensive resistance profiling and tracking of resistance patterns from environmental reservoirs to animal or human populations. The cultivation approach not only provides direct phenotypic evidence of bacterial resistance but also serves as the basis for subsequent strain isolation and further identification or testing.

The primary strengths of culture-based methods lie in their ability to provide direct phenotypic evidence of bacterial resistance while yielding viable isolates for subsequent molecular analysis. Standardized protocols ensure reproducible results across laboratories, making this approach particularly valuable for regulatory compliance and inter-laboratory comparisons. However, these methods face significant limitations in environmental surveillance, particularly cultivation bias, as only 1%–10% of environmental bacteria are cultivable under standard laboratory conditions, potentially leading to substantial underestimation of the true extent of environmental AMR. Additionally, the time-intensive nature (24–48 h) limits real-time detection capabilities, and the method may miss viable but nonculturable (VBNC) bacteria that could harbor resistance genes, representing a critical gap in comprehensive environmental AMR assessments (Table 1).

Table 1. Classic and emerging methods for quantitative and qualitative surveillance of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and genes

Principles Advantages Limits Target Quantitative/ qualitative Ref. Phenotypic methods Culture-based Bacterial growth Standardized process; quantification Time-consuming; low throughout Isolator Quantitative [15,43,44] Flow cytometry Fluorescence counting Rapid; portable; single cell Small scale and volume Cell Quantitative [16] Raman spectroscopy Inelastic scattering or Raman scattering Rapid; label-free; single cell Limited bacterial species; low resolution Cell Qualitative [49−51] MALDI-TOF/MS Mass-to-charge ratio Rapid; label-free; high throughput High instrumental cost; culture-dependent Protein Qualitative [62−64] Genotypic methods PCR ARGs' conserved primer region High sensitivity; culture-free Unavailable information on resistome (ARG host, pathogenicity); restricted detection of unknown ARGs DNA Quantitative [68,69,72] CRISPR-Cas Cas protein cleavage High sensitivity/accuracy; Culture-free Limit bacterial species DNA/RNA Quantitative [17,83] Metagenomics ARG sequences High-throughput; information on the resistome (ARG host, pathogenicity); detection of new ARGs Requirement for expertise in bioinformatics; lack of standard protocol DNA Relative abundance [87,90] Integrated methods Phenotypic screening and genomics Comprehensive detection; enhanced accuracy; targeted surveillance Complex workflow; higher cost; technical expertise required Cell and DNA Quantitative/

qualitative[41,109,

111−113]Optical techniques

-

Optical techniques have emerged as transformative tools for environmental AMR surveillance, offering rapid, real-time detection capabilities that address the key limitations of traditional culture-based approaches. These methods leverage the transduction of bacterial growth and metabolic signals into quantifiable optical outputs, reducing detection times from 1–2 d to within hours and enabling timely guidance for antibiotic stewardship[45]. The primary optical techniques employed in environmental AMR surveillance include flow cytometry, which utilizes fluorescent signals for bacterial enumeration and HGT monitoring, and Raman spectroscopy, which provides label-free biochemical fingerprinting at a single-cell resolution. Together, these complementary approaches enable comprehensive characterization of environmental resistomes while overcoming the cultivation bias inherent in traditional methods.

Flow cytometry has established itself as a versatile platform for environmental AMR surveillance, using differential fluorescent labeling to assess bacterial abundance, viability, and antibiotic resistance across diverse environmental matrices[16,46]. The methodology involves suspending bacteria in culture solutions containing antibiotics followed by fluorescent staining to distinguish viable from nonviable cells[47]. This approach provides quantitative resistance profiles while maintaining compatibility with complex environmental samples. Beyond detecting conventional resistance, flow cytometry excels in monitoring HGT events, a critical mechanism driving the dissemination of AMR in environmental settings. The technique enables simultaneous detection and quantification of donor, recipient, and transconjugant populations through differential fluorescent labeling, facilitating real-time assessment of HGT's efficiency under varying environmental conditions, including temperature gradients, nutrient availability, and microbial community dynamics[48]. Advanced applications incorporating cell-sorting capabilities allow direct isolation of transconjugant cells from environmental samples, facilitating downstream molecular characterization of the transferred resistance genes. Additionally, metabolic activity-based approaches, such as biorthogonal noncanonical amino acid tagging, have demonstrated particular efficacy in determining bacterial resistance in aquatic environments[16].

Complementing flow cytometry's capabilities, Raman spectroscopy offers a fundamentally different approach to AMR surveillance by providing label-free biochemical fingerprinting of environmental bacteria[49−51]. As a nondestructive analytical technique, Raman spectroscopy delivers intrinsic phenotypic information at a single-cell resolution, profiling physiological and biochemical states including metabolic activity and gene expression patterns[52]. This capability enables direct identification of metabolically active resistant cells through spectral analysis of antibiotic-exposed bacteria. The technique's discriminatory power is enhanced through stable isotope labeling (SIP), which directly links functional activity to microbial identity in complex environmental samples. In Raman-SIP applications, Raman spectral shifts occur when biomolecules incorporate heavy isotopes (e.g., 13C, 15N, or 2H) during active metabolism, enabling precise identification of metabolically active ARG hosts at the single-cell level[53,54]. Such integrated Raman-SIP approaches have demonstrated remarkable versatility across environmental applications, from identifying active antibiotic-degrading populations in wastewater systems to characterizing phenotypic AMR profiles in soil microbial communities and simultaneously revealing the taxonomic identity of resistant bacteria that remain unculturable by traditional methods[55−57]. These combined methodologies enable the tracking of metabolic activity, antibiotic uptake, and ARG transfer in environmental bacteria, providing mechanistic insights into the processes of resistance and host–pathogen dynamics at an unprecedented resolution.

These optical techniques collectively offer substantial advantages for environmental AMR surveillance, including rapid detection and in situ analysis without requiring bacterial cultivation. Flow cytometry enables direct quantification of ARB's prevalence and comprehensive HGT monitoring in natural microbial communities, whereas Raman spectroscopy provides single-cell resolution for analyzing metabolically active resistant cells, including previously unculturable populations. Both approaches can process complex environmental samples with minimal preparation, representing significant advances in real-time environmental monitoring capabilities. However, these promising methodologies face inherent limitations that must be considered for comprehensive environmental surveillance strategies. Flow cytometry requires fluorescent labeling that may not accurately reflect natural bacterial states and its HGT monitoring applications require careful optimization of labeling strategies that may be influenced by environmental factors affecting the efficiency of conjugation. Raman spectroscopy encounters challenges in species-level bacterial identification resulting from the complexity of spectral interpretation and requires specialized data analysis expertise to distinguish resistance-related spectral features from environmental interference. Additionally, both techniques require sophisticated equipment and trained personnel, potentially limiting their widespread adoption for routine environmental monitoring, despite their promising applications for comprehensive environmental AMR surveillance, including detecting resistance, monitoring gene transfer, and analysis of unculturable bacterial populations.

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight biotyping

-

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF/MS) has emerged as a transformative technology for precise and rapid microbial identification, significantly enhancing the capacity to biotype bacterial pathogens across diverse sectors including clinical diagnostics, food safety monitoring, and pharmaceutical quality control[58,59]. This proteomics-based approach has gained prominence in food industry applications, where rapid identification of foodborne pathogens and spoilage organisms is critical for ensuring product safety and extending shelf life. Similarly, in clinical settings, MALDI-TOF/MS enables the rapid diagnosis of bacterial infections, facilitating timely antimicrobial therapy decisions.

The analytical workflow involves placing microbial colonies onto MALDI target plates, followed by co-crystallization with organic matrices, enabling identification by detecting peptides' and small proteins' molecular weights on the basis of mass-to-charge ratios[60]. This label-free approach delivers species identification and resistance profiling within minutes, representing substantial time savings compared with traditional culture-based methods and offering advantages over optical sensor technologies in terms of specificity and throughput. Beyond conventional identification, MALDI-TOF/MS demonstrates significant capabilities for AMR detection through rapid, reliable microbial screening[61]. For instance, β-lactamase activity can be determined by monitoring mass spectral changes in β-lactamase-producing bacteria following exposure to β-lactam antibiotics[62]. The flexible sample preparation process accommodates both direct bacterial cell transfer and protein extraction protocols, with the latter exemplified by protein extraction from extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing E. coli for determining resistance[63]. The discriminatory power of the method extends to complex resistance phenotypes, facilitating the accurate categorization of multidrug-resistant pathogens, such as carbapenem- and colistin-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates, based on characteristic mass spectral signatures[63,64].

Despite its advanced capabilities and promising potential for environmental AMR surveillance, MALDI-TOF/MS faces several implementation challenges. The substantial initial instrument cost represents a significant barrier to its widespread adoption, particularly for smaller laboratories and routine environmental monitoring programs. More critically, the current reference databases lack the taxonomic diversity needed to identify the broad spectrum of environmental bacterial species present in natural ecosystems[65]. This limitation is compounded by frequent low identification scores, which necessitate additional sequencing-based confirmation, thereby reducing the method's efficiency advantages. Moving forward, expanding MALDI databases represents an essential priority for realizing the full potential of this technology in environmental applications. Comprehensive database development, particularly for previously unanalyzed environmental habitats, would enable the rapid identification of environmental bacterial isolates and support the broader implementation of MALDI-TOF/MS in environmental AMR surveillance programs. Such expansion would bridge the current gap between the method's demonstrated capabilities in clinical and food industry applications and its potential contributions to environmental resistome monitoring.

Genotypic methods

Polymerase chain reaction

-

PCR has been widely applied for the detection of target DNA using specific primers[66]. Hence, PCR is widely employed for the identification of target ARGs in environmental DNA samples, with the advantages of speed and high sensitivity[67]. Furthermore, with the increasing need for detecting multiple targets and time efficiency, multiplex PCR has emerged as an application. Multiplex PCR allows the simultaneous detection of multiple ARGs by incorporating multiple primers within a single reaction[68,69]. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) enables quantitative analyses of specific ARGs in environmental DNA samples. Furthermore, absolute quantification of ARGs can be achieved by comparing the results with standard curves generated from standard DNA sequences of known concentrations[70,71]. However, the presence of numerous ARG variants in the environment necessitates multiple qPCR assays for comprehensive detection, thereby increasing both the analytical time and costs. To address this limitation and facilitate simultaneous quantification of diverse ARGs, researchers have developed high-throughput qPCR (HT-qPCR) technology[72]. This methodology offers several advantages, including time efficiency, operational simplicity, and reduced requirements for bioinformatic expertise, thereby leading to its widespread application for the simultaneous quantification of tens to hundreds of target ARGs across diverse environmental habitats such as soil[73], wastewater[74], and air[75]. Environmental applications have shown that multiplex PCR can effectively screen for up to 229 different resistance genes simultaneously, with studies in wastewater revealing the presence of carbapenemase genes (blaOXA) alongside extended-spectrum β-lactamase genes in over 70% the of samples tested[76]. Digital PCR (dPCR) technology employs emulsion-based partitioning of nucleic acids and probes into oil-encapsulated droplets, effectively mitigating primer bias during PCR amplification[77]. Recent applications of dPCR in environmental monitoring have demonstrated superior sensitivity and precision compared with conventional qPCR. For example, dPCR has been used to quantify sul1 and qnrB genes in environmental samples at concentrations as low as 5 copies/mL, providing more accurate risk assessment data for drinking water sources[78].

Although PCR-based methods are widely applied for rapid and sensitive detection of single or multiple target ARGs in routine environmental monitoring, they also suffer from false negative or false positive amplifications, primer selection and amplification-related bias, and relatively high per-gene costs. Even HT-qPCR, which is typically applied, usually detects no more than 300 ARGs, covering only ~10% of the currently known ARG repertoire. Furthermore, PCR-based methods are unable to elucidate the critical characteristics that determine the dissemination and health risks of ARGs, such as host identity, pathogenicity, and multi-resistance. Additionally, these PCR-based techniques cannot support core environmental resistome research tasks, including investigating the emergence, fate, evolution, activity, and transmission of environmental ARGs. Consequently, these limitations constrain comprehensive assessments of the ecological and health risks of environmental ARGs and necessitate quantitative meta-omics (e.g., metagenomics and metatranscriptomics) analyses of antibiotic resistomes, as discussed later.

CRISPR-Cas-based methods

-

As a next-generation diagnostic methods, CRISPR-based tools and approaches with Cas-9, Cas-13, and Cas-12 proteins have revolutionized nucleic acid detection and disease diagnosis[79]. CRISPR/Cas systems are naturally found in prokaryotic organisms and encode Cas proteins to defend against viral invasion. This disruptive technology was first applied for detecting viruses using CRISPR-Cas-9, which was subsequently combined with isothermal amplification to further improve detection sensitivity[80,81]. Among the Cas family members, Cas-12, Cas-13, and Cas-14 can cut the target nucleic gene in single-strand DNA (ssDNA), double-strand DNA (dsDNA), and single-strand RNA (ssRNA), respectively. More importantly, cleavage of irrelevant nontarget nucleic acids, such as ssDNA or ssRNA, can also be triggered. According to this principle, the CRISPR-Cas system has been used to detect infectious viruses and pathogens in food, clinical, and environmental samples with high sensitivity, specificity, and stability[82].

Similarly, CRISPR-Cas-based methods can be used for detecting ARGs using designed primers. For example, Curti et al. reported a CRISPR-based platform for tracking carbapenem resistance (carbapenemase) genes and viral RNA sequences, with a detection limit of 1 amol using Cas-12a[17]. Moreover, Cheng et al. demonstrated the application of a convenient one-step approach for the rapid detection of several ARG markers (sul1, qnrA-1, mcr-1, and intl1) in urban water by integrating CRISPR-Cas-12 and recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA) with optimized suboptimal protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) groups[83]. In summary, CRISPR-Cas systems exhibit commendable performance in their preliminary applications, and their broader application for monitoring ARGs is emerging, especially for environmental samples that have far greater compositional complexity than clinical samples. The high sensitivity of this innovative method represents a distinct advantage for identifying the target ARB or ARG in complex environmental microbiota samples. However, challenges remain because of interference from nontargets and heavy metal ions, which need to be addressed.

Metagenomic sequencing

-

Compared with classic PCR or the emerging CRISPR-Cas-based methods, metagenomic sequencing offers notable advantages beyond decoding microbial community DNA, including the ability to overcome primer constraints, reduce amplification bias, and eliminate false negative results caused by environmental enzyme inhibitors. In particular, a metagenomic approach equipped with a structured database of ARGs and a Python bioinformatics pipeline was developed to realize the simultaneous and unprecedentedly high-throughput detection of ARGs in environmental samples[84,85]. This approach supported the subsequent establishment of the online server ARG-OAP[86] and motivated the later development of quantitative metatranscriptomic[33] and phenotypic metagenomic approaches for analyzing the expression patterns and bacterial hosts of environmental ARGs, respectively. The wide application of these approaches has dramatically enhanced our understanding of environmental and human resistomes in the last decade[30,87,88].

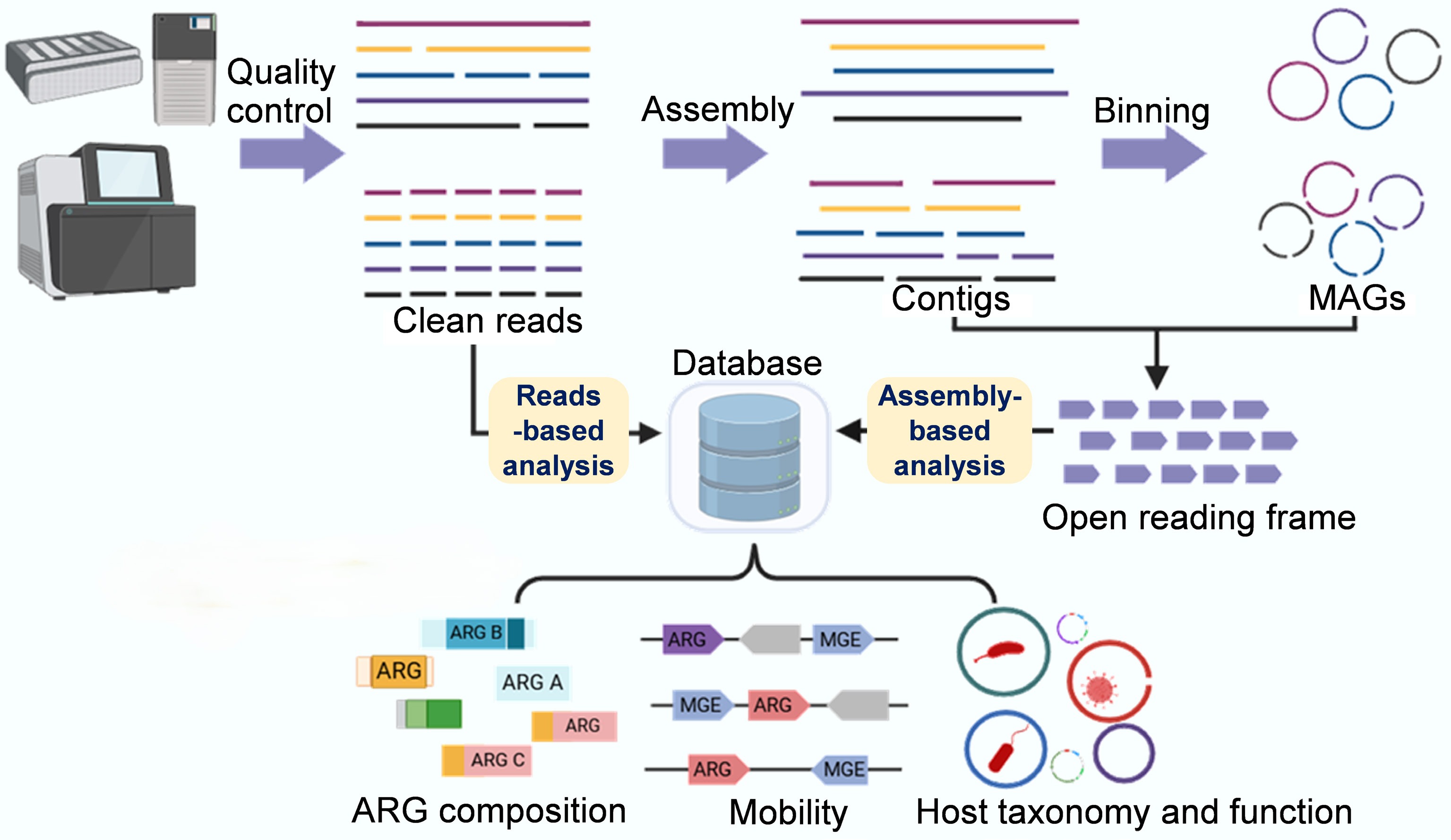

Metagenomic analysis of environmental ARGs and other functional genes involves a series of complex bioinformatics procedures, from data preprocessing to statistical analysis and visualization[89]. The process typically begins with obtaining raw short reads, followed by initial quality control to produce clean reads. These reads are then subjected to de novo assembly and binning to generate high-quality microbial genomes. The two main bioinformatics strategies in metagenomic analysis are read-based and assembly-based, both relying on database searches (Fig. 3)[89,90]. The main reference databases commonly used for identifying ARGs from (meta)genomic assemblies include the Antibiotic Resistance Genes Database (ARDB)[91], the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD)[92], and the Structured Antibiotic Resistance Gene database (SARG)[93]. Read-based approaches directly align short reads to the reference databases, offering computational efficiency for profiling ARGs' diversity, composition, and abundance across environmental, animal, and human reservoirs[94−96]. However, this method is susceptible to false positives arising from the mis-assignment of short reads (typically 150–300 bp) to homologous sequences in nonresistance genes, incomplete or redundant database entries, and variations in the alignment algorithms and threshold parameters across bioinformatics tools (e.g., BLAST, DIAMOND, BWA)[97,98]. The choice of software and database significantly impacts the detection outcomes, as stringent thresholds (≥ 95% identity, ≥ 80% coverage) reduce false positives but may miss divergent variants. In contrast, relaxed thresholds increase sensitivity at the cost of specificity, leading to ARG abundance estimates that can vary by orders of magnitude across tool–database combinations. To address these limitations, best practices include using multiple complementary databases with cross-validation, employing conservative thresholds appropriate to the research objectives, manual curation of high-priority genes, and experimental validation of novel resistance determinants. In contrast, assembly-based analysis substantially mitigates false positives by providing extended sequence contexts that enable more confident discrimination between genuine ARGs and homologous nonresistance genes. However, the assembly's quality remains dependent on the sequencing depth, the community's complexity, and the choice of assembler (e.g., MEGAHIT, metaSPAdes, IDBA-UD), with variable contig completeness affecting the accuracy of downstream detection. Recent applications of assembly-based approaches have successfully elucidated ARGs' diversity in municipal and hospital WWTPs while decoding their mobility potential and host characteristics, thereby offering critical insights for assessments of wastewater-associated resistance risk[30,87,99].

Figure 3.

Metagenomic sequencing-based analysis workflow of ARGs and resistomes. The basic traits of the resistome, including the diversity, abundance, and composition of ARGs, can be comprehensively analyzed using a short-read-based approach (which sensitively detects rare or hard-to-assemble species and genes). Key traits of the resistome, such as mobility, host pathogenicity, and multi-resistance, can be qualitatively analyzed using an assembly-based approach that produces metagenome-assembled genomes and longer contigs, thereby achieving refined taxonomic and phylogenetic resolution and improved functional insights.

Furthermore, with the development of metagenomic sequencing technologies, third-generation long-read sequencing has addressed the limitations of short-read or shotgun sequencing in generating ultra-long reads. A critical challenge in resistome research has been the accurate characterization of mobile genetic elements (MGEs), such as plasmids, integrons, and transposons, which are typically characterized by repeat-rich sequences that confound short-read assembly methods. Long-read metagenomic sequencing technologies, such as Oxford Nanopore and PacBio HiFi, enable the assembly of complete or near-complete genomes of specific microbial species or even strains[100]. The key to this capability lies in the extended read length (10–100 kb or longer), which allows unambiguous resolution of repetitive regions and complete reconstruction of MGE structures. These features are routinely fragmented or misassembled in short-read approaches[100,101]. This technical advantage translates into critical downstream benefits: It enables accurate mapping of ARG contexts within MGEs, determination of their complete genetic architecture, and tracking of HGT events, which are tasks that are nearly impossible with short-read sequencing alone. Consequently, the improved detection of ARGs and comprehensive evaluation of host-related contextual information and functional potential enabled by long-read sequencing directly stem from its unique capacity to span entire mobile genetic elements in single reads, thereby preserving the complete genetic context of the determinants of resistance[102,103]. Beyond enhanced assembly quality, long-read sequencing also demonstrates superior sensitivity for detecting low-abundance resistance elements. A recent study reported the rapid in situ application of Nanopore sequencing to detect low-abundance plasmid-mediated resistance that was often undetectable by conventional methods, demonstrating how long-read technology can capture complete plasmid sequences and their ARG cargo with unprecedented clarity[104]. This combination of structural resolution and detection sensitivity positions long-read sequencing as an indispensable tool for comprehensive characterization of resistomes in environmental surveillance.

In summary, metagenomic sequencing has significantly enhanced our comprehensive understanding of the determinants of resistance (i.e., ARGs and ARB) within environmental settings. This culture-independent technology offers a more comprehensive and impartial approach for characterizing resistome profiles and the functional characteristics of resistant bacteria, compared with culture-dependent phenotypic AST and primer-dependent PCR detection methods. Moreover, the advent of third-generation long-read sequencing technologies has further revolutionized access to the important genomic data of uncultured environmental bacteria. Critically, long-read sequencing provides the only reliable means of completely resolving complex, repeat-rich mobile genetic elements, thereby enabling a more detailed exploration of crucial ARGs' resistance features, such as mobility, host specificity, pathogenicity, and multi-resistance[105]. Metagenomic sequencing of microbial communities, though powerful for its broad-spectrum, struggles to capture and accurately profile resistant bacteria and pathogens that are usually present with low abundance in complex environmental and nonclinical samples. This limitation arises from the trade-off between broad-spectrum coverage and sensitivity in bulk metagenomics and can be overcome by integrating it with complementary methods that select and prioritize the microbiota members of primary interest in downstream metagenomic sequencing.

Integrated methods

-

The complexity of environmental AMR necessitates integrating multiple surveillance approaches to overcome the inherent limitations of individual methods. As summarized in Table 1, phenotypic methods provide direct determination of resistance and bacterial identification based on cellular or protein responses, but fail to comprehensively characterize resistome profiles. Conversely, genotypic methods enable accurate detection of the target genes and characterization of the resistome, yet require expert analysis to interpret the functional significance of the detected genetic elements[106]. A critical challenge in AMR surveillance is the discrepancy between the phenotypic and genotypic results, highlighting significant gaps in our understanding of resistance mechanisms[106]. The relationship between genotype and phenotype is not always straightforward, as environmental conditions and genetic context significantly influence expression of ARGs[107]. This complexity is exemplified by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which exhibits high-level tobramycin resistance exclusively under biofilm conditions[108], demonstrating how environmental factors can modulate resistance phenotypes independently of the genetic determinants.

To address these challenges, several integrated workflows have been developed for comprehensive assessments of AMR. Traditional approaches combine antibiotic-amended selective culture media with WGS to analyze resistant isolates. This strategy provides functional insights into the resistome's spectra and the plasmid-encoded mobile resistance elements of clinically important bacterial strains. Additionally, sequence-based typing enables phylogenetic analysis to track the dissemination of resistance. An emerging approach that combines metagenomic sequencing of culture-enriched microbiota following phenotypic screening has proven particularly effective for monitoring rare but clinically significant ARGs, such as carbapenemases and extended-spectrum β-lactamases, in environmental and human microbiomes[41,109,110]. This approach is promising for standardized resistome surveillance because it can effectively assign the tested resistance phenotype of the microbiota's members to both known and novel genotypes, addressing the challenges of complex interference from environmental samples through comprehensive genetic profiling of key traits of the resistome, such as mobility, host pathogenicity, and multi-resistance. Building upon these phenotype–genotype integration strategies, culture-independent metagenomics and metatranscriptomics profiling have emerged to capture the full spectrum of resistance potential and its functional expression in complex microbiomes. Comparative studies have revealed differential expression of the resistome across human, chicken, and pig gut microbiomes, showing that ARG expression patterns vary significantly among hosts, even when similar resistance genes are present[111]. This transcriptomic dimension is particularly valuable for risk assessment at critical One Health interfaces; for example, investigations at live poultry markets demonstrated more diversified ARG profiles and expression patterns in chickens and occupationally exposed workers compared with the controls[112]. These findings underscore that comprehensive AMR surveillance requires understanding transcriptional dynamics and functional expression across the human–animal–environment continuum, not merely cataloging resistance genes. Recent technological advances are further expanding the possibilities for integrated AMR surveillance. Culture-free approaches, such as Raman spectroscopy sorting coupled with genotypic methods, enable in situ investigations of ARB in environmental settings[113]. These developments represent a paradigm shift toward real-time, noninvasive AMR monitoring capabilities.

The integration of phenotypic and genotypic methods represents the future direction of AMR surveillance, offering the potential for standardized resistome monitoring protocols. Despite the existing knowledge gaps, the complementary nature of these approaches provides a more complete understanding of environmental AMR dynamics. The continued development of multimodal integration strategies, combining traditional culture methods with advanced molecular techniques and emerging technologies, holds promise for achieving comprehensive, real-time AMR surveillance systems capable of addressing the complexity of environmental resistomes.

-

The escalating AMR crisis demands urgent, coordinated intervention strategies that extend beyond traditional clinical boundaries to encompass environmental, agricultural, and human health domains[2]. This multifaceted challenge necessitates coordinated global action plans leveraging the One Health approach to integrate surveillance, research, and management strategies for ARGs and ARB as emerging environmental contaminants[6]. Central to this comprehensive strategy is the recognition that AMR transcends traditional sectoral boundaries, creating persistent environmental reservoirs that can bypass conventional clinical containment measures. Therefore, successful mitigation requires integrated interventions across human, animal, and environmental health domains, implemented through two primary strategic approaches: source control measures that address the fundamental drivers of AMR emergence and dissemination, and process control technologies that intercept and neutralize elements of resistance during their transmission pathways. Together, these complementary strategies form a robust framework designed to break the transmission cycle of resistance and safeguard global health through evidence-based, technologically advanced, and ecologically sustainable solutions.

Global threats and the One Health response to environmental AMR

-

Antimicrobial resistance extends far beyond clinical settings, as AMR exemplifies a truly interconnected threat where resistant strains and ARGs circulate freely across the human, animal, and environmental domains, creating complex resistance networks that span multiple ecosystems[114]. Environmental reservoirs play a particularly critical role in this global resistance web, serving as both recipients and sources of AMR. Under antibiotic selection pressure, ARB can dominate microbial communities, dramatically reducing biodiversity and compromising essential ecosystem functions such as nutrient cycling and organic matter decomposition[8]. More critically, ARGs propagate through multiple interconnected routes, from soil bacteria to plant endophytic communities[115,116], along food chains via predator–prey interactions[117], and ultimately to human populations through food consumption[118]. This environmental circulation creates persistent reservoirs of resistance that can bypass traditional clinical containment strategies.

The One Health framework emerges as the most viable approach to address these multifaceted challenges by integrating surveillance and intervention strategies across all health domains[4]. Current global initiatives, including the International Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring (InFARM) platform and the Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS), have established effective monitoring in clinical and agricultural settings[119]. Despite these advances, a critical gap in environmental surveillance remains, where the absence of internationally standardized methodologies fundamentally limits our ability to implement truly comprehensive One Health approaches.

To address this surveillance gap and effectively prioritize mitigation strategies, systematic risk assessments and tools for the stratification of AMR are essential. Risk levels of AMR should be evaluated across four interconnected dimensions: (1) Clinical risk, determined by the prevalence of resistance in priority pathogens and therapeutic alternative availability; (2) transmission risk, based on ARGs' mobility, host range, and cross-compartmental dissemination potential; (3) evolutionary risk, considering capacity for HGT and co-selection mechanisms; and (4) ecological risk, assessing environmental persistence and re-entry potential into human and animal populations. Risk-ranking frameworks integrating these dimensions would enable the prioritization of monitoring efforts and targeted interventions[120,121]. High-risk scenarios, such as carbapenemase genes (blaNDM, blaKPC) in urban wastewater or mobile colistin resistance (mcr) in agricultural settings, warrant immediate intensive responses, whereas chromosomally encoded resistance with limited mobility requires less urgent action. Importantly, NGS technologies have expanded this risk landscape by revealing previously undetected microbes harboring clinically relevant ARGs in environmental reservoirs. Risk stratification of these newly identified organisms requires us to evaluate their phylogenetic proximity to known pathogens, their carriage of mobile genetic elements, and their potential for zoonotic transmission[36]. This comprehensive risk assessment framework, encompassing both established resistance determinants and NGS-discovered microbes, would allow systematic identification of priority resistance threats and inform evidence-based monitoring and mitigation strategies that effectively bridge the human, animal, and environmental health sectors. Moving forward, integrating standardized risk assessment protocols with environmental surveillance networks represents the crucial next step toward achieving comprehensive global AMR management under the One Health paradigm.

Mitigation strategies and approaches for AMR

Source control

-

Source control represents the most fundamental and cost-effective strategy to mitigate the development and spread of ARB and ARGs in environmental reservoirs by addressing the root causes of AMR contamination. Promoting the rational use of antibiotics is the most direct and effective measure for mitigating AMR by decreasing the export of antibiotics, ARGs, and ARBs into the environment[122]. ARB will decrease as selection pressure declines and antibiotic loads diminish over time[123]. Restricting antibiotic use will reduce residues in hotspots such as livestock farms, medical facilities, WWPTs, and human communities, effectively mitigating AMR's emergence, selection, and environmental transformation. However, significant global disparities exist in antibiotic use management, with low-income countries showing poorly regulated antibiotic use and limited AMR surveillance data[124]. Complementing regulatory approaches, pollution-reduction strategies are equally crucial, as environmental pollution promotes ARB's proliferation through the evolutionary processes of selection, co-selection, and cross-selection[125]. Therefore, decreasing pollution can also reduce co-selection pressure and the abundance of bacteria carrying ARGs.

Beyond policy interventions, innovative biological and technological approaches offer promising solutions for source control. Biological degradation approaches, including enhanced biodegradation of antimicrobials, can significantly reduce the selective pressure that drives the conjugative transfer of ARGs through both natural biodegradation processes and engineered bioaugmentation systems using specific bacterial strains capable of efficiently degrading antimicrobial compounds in environmental matrices[126]. Moreover, antimicrobial biodegradation has been demonstrated to diminish the transcription of key genes involved in conjugation and thereby curb ARGs' transfer, underscoring its crucial role in lowering the abundance of high-risk pathogenic microorganisms in microbial communities[127]. Green chemistry and sustainable design strategies focus on developing environmentally benign antimicrobials with improved biodegradability and reduced environmental persistence, including designing antibiotics that degrade more readily under environmental conditions and developing alternative antimicrobial strategies such as antimicrobial peptides and bacteriophages[128]. Agricultural and industrial stewardship involves precision dosing systems, improved animal husbandry practices, cleaner production technologies in pharmaceutical manufacturing, and point-of-use treatment systems that capture antibiotics and ARB before environmental release.

Process control

-

Process control focuses on intercepting and treating AMR elements during their transmission pathways, particularly in wastewater treatment and waste management systems, serving as critical barriers when source control measures are insufficient. Conventional treatment technologies in WWTPs depend on both biological treatment processes and disinfection methods including chlorination, ultraviolet (UV), and ozonation[129]. Chlorination is the most widely used disinfectant in global wastewater treatment processes, as it is capable of removing approximately 90% of ARGs through bacterial inactivation and ARG damage[130]. However, its effectiveness is limited to liquid effluent, with ARGs in solid streams remaining largely unaddressed, and some waterborne ARB are tolerant to chlorine, indicating incomplete removal of the AMR risk[131]. UV disinfection (200–260 nm) targets bacterial DNA to inactivate microorganisms[132], whereas UV treatment can substantially reduce ARB populations; however, ARGs may remain active and capable of disseminating AMR in ecosystems[133]. Advanced oxidation and membrane technologies, including ozonation and membrane-based systems, can effectively reduce bacterial loads, but their high costs limit their widespread application[134].

Advanced and emerging treatment technologies offer enhanced AMR removal capabilities with greater specificity. Hyperthermophilic composting demonstrates remarkable elimination of ARGs (~90%) compared with conventional composting, particularly effective against aminoglycoside and macrolide resistance, as arapid temperature increase to ~90 °C negatively affects the bacterial community's stability and ARGs' persistence[135,136]. Optimizing the composting conditions, including the temperature, bulking agents, and C/N ratio, can improve treatment safety and efficiency[137]. Nonetheless, the mechanisms by which microorganisms drive the humification of organic matter and mediate pollutant migration still need to be explored for this technology.

Emerging selective removal technologies target specific ARG and ARB populations using nanotechnology, CRISPR-Cas systems, bacteriophage therapy, and engineered bacterial systems[138]. Among these, nanomaterials can be used as antimicrobial agents to induce and damage the membrane of ARB because of their nano-size-related properties[139]. However, the toxicity, performance, and cost-effectiveness of nanomaterials in real treatment processes require further research and careful management[140]. CRISPR-Cas technology has significant potential to combat AMR by selectively targeting the genes responsible for antibiotic resistance, biofilm formation, and virulence the pathogens prioritized by the WHO[141]. However, clinical translation faces key challenges, including optimizing delivery systems (plasmids, bacteriophages, nanoparticles), preventing the development of resistance, and addressing the regulatory barriers[142]. Despite its revolutionary potential, the technology requires further optimization before its widespread clinical application[143]. Bacteriophage therapy plays a dual role, as bacteriophages function both as potential vectors and targeted weapons against the transmission of antibiotic resistance in hospital wastewater systems[144]. Lytic phages have been reported to specifically eliminate ARB populations in WWTPs while minimizing their impact on beneficial microbial communities, whereas conventional disinfectants show reduced efficacy[145]. Engineered bacterial systems represent an innovative approach using DNA scavengers to capture and degrade free-floating ARGs in wastewater environments[146]. Complementing this technological approach, recent ecological studies have identified specialized organisms and environmental factors that naturally combat the dissemination of antibiotic resistance by restricting the growth, metabolism, adaptation, and HGT mechanisms of ARB[147]. These precision-based technologies offer targeted specificity in AMR control. The integration of engineered systems with natural ecological processes provides a comprehensive framework for combating the proliferation of antibiotic resistance. However, several critical challenges must be addressed before their widespread implementation, including the potential emergence of anti-CRISPR resistance mechanisms. These off-target effects may disrupt beneficial microbial communities, impede the development of appropriate regulatory frameworks for genetically modified organisms in environmental applications, and necessitate comprehensive safety assessments to evaluate the long-term ecological impacts. Addressing these challenges through rigorous research and regulatory oversight will be essential for optimizing the practical applications of engineered bacterial systems in mitigating environmental AMR.

-

This comprehensive review underscores that environmental AMR constitutes a critical component within the One Health framework, requiring integrated surveillance and mitigation strategies that reflect its complex role across the environmental, animal, and human health domains[18,124]. Our analysis consolidates three overarching insights that are essential for future environmental AMR management: the necessity of methodological integration in surveillance, the urgency of establishing global standards, and the importance of focusing mitigation on key risk-defining resistome traits.

First, environmental AMR surveillance demands robust methodological integration rather than reliance on isolated approaches, given its high complexity and dimensionality. Although phenotypic methods, including culture-based approaches, optical techniques, and MALDI-TOF biotyping, provide essential capabilities for detecting viable pathogens and characterizing resistance, they are constrained by cultivation bias, time limitations, and incomplete databases for environmental taxa. In contrast, genotypic tools such as PCR-based detection, CRISPR-Cas systems, and metagenomic sequencing enable broad resistome profiling and rapid detection, though they may overlook expressed resistance and be subject to matrix-related interference. An integrated strategy, combining culture-enhanced phenotypic screening with high-resolution genotyping[41], offers a synergistic solution, enabling the detection of both cultivable and uncultivable resistant populations while clarifying the genetic mechanisms and dissemination pathways of resistance.

Second, a significant obstacle to coherent global surveillance remains the lack of standardized protocols and procedures. Environmental samples' diversity, from wastewater and soil to agricultural and aquatic systems, necessitates tailored treatments (e.g., sample-specific pretreatment) and analytical workflows, complicating the establishment of universal standards. However, standardization is indispensable for generating comparable, reproducible data across laboratories, monitoring programs, and regions. Future efforts should prioritize the development of adaptable yet consistent frameworks that accommodate environmental variability while ensuring the data's interoperability, particularly for metagenomic applications, where harmonized bioinformatic pipelines and curated reference databases are urgently needed to enable improved global surveillance networks[148,149].

Third, effective mitigation of environmental AMR should prioritize key resistome traits over exhaustive gene cataloguing. Our assessment highlights three traits as central to public health: ARGs' mobility (governing HGT), host pathogenicity (indicating clinical relevance), and multi-resistance profiles (constraining treatment options)[30,33]. These key traits collectively influence the outcomes of human exposure (including risks) and should inform both surveillance design and intervention planning. Accordingly, source control measures, such as optimized wastewater treatment, antibiotic stewardship in agriculture, and enhanced controls on pharmaceutical emissions, should be implemented alongside process-oriented interventions that disrupt the transmission routes of resistance within environmental compartments.

Looking forward, several technological and strategic advances will strengthen environmental AMR governance from the perspectives of surveillance and mitigation. The convergence of high-throughput metagenomics with machine learning promises the enhanced detection and prioritization of resistance determinants in complex environmental samples, whereas expanded MALDI-TOF databases and portable genomic tools will enhance rapid, field-deployable identification. Equally importantly, integrating surveillance outputs with predictive ecological and epidemiological models will enable proactive risk mapping and targeted intervention. Achieving these goals, however, requires coordinated global efforts to establish standardized practices, expand the monitoring infrastructure, and advance evidence-based mitigation policies fully aligned with the One Health perspective. Ultimately, addressing environmental AMR requires acknowledging that the environment acts not only as a reservoir of ARGs but also as a dynamic arena for their emergence, evolution, and cross-domain spread. Success in managing this escalating threat will depend on sustained commitment to integrated surveillance, standardized methods, and trait-focused mitigation that ensure the environmental dimensions of AMR are adequately addressed within global health security agendas.

The authors would like to thank Xiaoxing Lin for assisting with the literature search.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception, design, and supervision: Feng Ju, Xinyu Zhu; data collection: Huilin Zhang, Yuqiu Luo; draft manuscript preparation: Huilin Zhang, Yuqiu Luo. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

This work was supported by the Muyuan Laboratory under Grant No.1136022401, Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. LR22D010001, and National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 51908467.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

ARG mobility, pathogenic hosts, and multi-resistance are key risk determinants.

Integrated phenotypic–genotypic surveillance is vital for accurate detection of antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

Standardized protocols are crucial for ensuring the comparability of global AMR data.

Targeted mitigation and technological advances strengthen AMR control via the One Health approach.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Huilin Zhang, Yuqiu Luo

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article. - Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang H, Luo Y, Zhu X, Ju F. 2025. Environmental antimicrobial resistance: key reservoirs, surveillance and mitigation under One Health. Biocontaminant 1: e022 doi: 10.48130/biocontam-0025-0023

Environmental antimicrobial resistance: key reservoirs, surveillance and mitigation under One Health

- Received: 11 October 2025

- Revised: 21 November 2025

- Accepted: 24 November 2025

- Published online: 18 December 2025

Abstract: Environmental antimicrobial resistance (AMR) represents a critical yet understudied dimension within the One Health framework, which emphasizes the interconnections of human, animal, and environmental health. This review systematically examines the sources and key reservoirs of environmental AMR, as well as surveillance and mitigation strategies for environmental resistomes. It begins by discussing the sources of AMR and identifying the primary reservoirs that sustain and disseminate resistance in the environment. Next, it summarizes both phenotypic and genotypic approaches for AMR surveillance and compares their advantages and limitations. This analysis underscores the need for integrated methods that combine phenotypic profiling of resistance capacity with genotypic characterization of antibiotic resistance genes, particularly their mobility and pathogenicity, to enable more accurate monitoring of clinically relevant resistome risks. Furthermore, the review summarizes global source and process control strategies to mitigate environmental AMR. Finally, it offers perspectives on future technological developments to enhance AMR surveillance capacity within complex environmental systems.