-

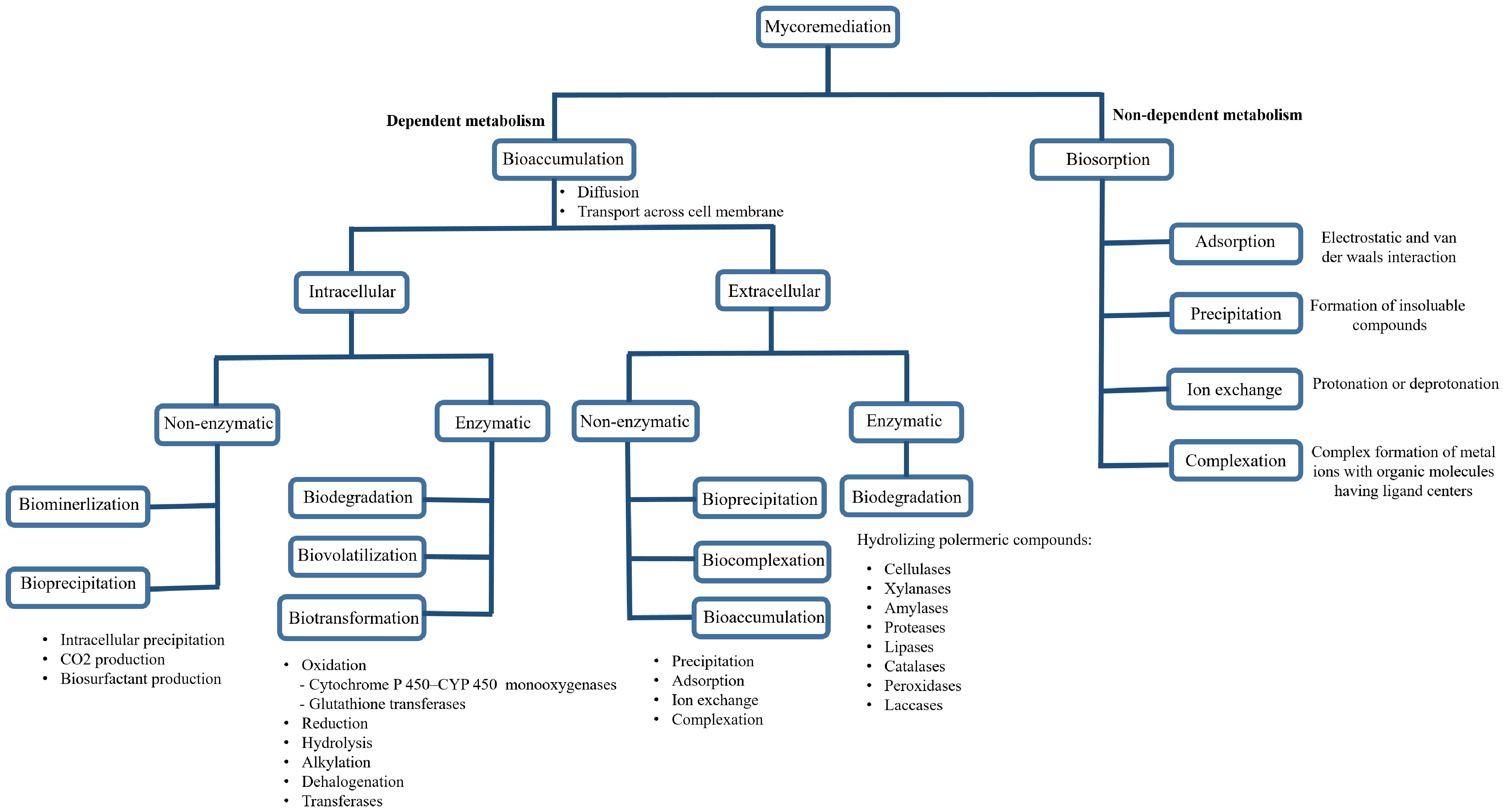

Environmental contamination by recalcitrant pollutants poses a global challenge due to their prolonged persistence in soil and other ecosystems. The recalcitrance of these substances indicates that current remediation methods are often insufficient or ineffective at breaking them down[1]. Consequently, there is an urgent need to develop novel strategies and technologies that can more effectively target and degrade these pollutants. Mycoremediation, a highly promising branch of bioremediation, employs fungi to degrade and detoxify environmental contaminants. Fungi have demonstrated a significant capacity to address environmental pollution through a diverse range of remediation approaches[2]. Numerous studies have reported the efficiency of fungi in reducing, transforming, or removing a wide array of pollutants, including heavy metals, metalloids, petrochemicals, polymers, pesticides, textile dyes, explosives, and radionuclides[3−6]. Fungi possess considerable potential for the biodegradation and biotransformation of various organic pollutants, whether they are in soluble or insoluble forms[7]. They utilize contaminants as substrates for growth by partially transforming or breaking them down into simpler and less toxic forms. The primary mechanisms employed in mycoremediation are biosorption and bioaccumulation[2]. Biosorption is a non-metabolism-dependent process that utilizes inactive fungal biomass to bind and sequester pollutants. In contrast, bioaccumulation is a metabolism-dependent process that involves the sequestration of pollutants through both chelation to the cell wall and subsequent active transportation into the fungal cell. Pollutant removal through this process is achieved via both enzymatic and non-enzymatic pathways and can occur either extracellularly or intracellularly[2,8].

Fungal remediation is facilitated by several key biological processes, including extracellular and intracellular enzymatic activities, bio-adsorption, biosurfactant production, biomineralization, and bioprecipitation. Specifically, filamentous fungi produce a diverse array of extracellular, non-specific enzymes such as laccases, peroxidases, cellulases, xylanases, amylases, proteases, lipases, and catalases that hydrolyze polymeric compounds and transform a wide range of organic pollutants. Similarly, intracellular enzymes catalyze diverse reactions that lead to the biotransformation of harmful substances. For example, the cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzyme system plays a key role in the elimination and degradation of organic pollutants by white-rot fungi[9]. These reactions encompass a variety of chemical processes, including oxidation (e.g., hydroxylation), reduction, hydrolysis, alkylation, dehalogenation, and transferase reactions[10]. A detailed overview of these mycoremediation techniques is presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

A detailed chart summarizing the mycoremediation techniques (adapted from Geris et al.[2]).

White rot fungi (WRF) are a group of fungi that are classified physiologically rather than taxonomically and are utilized in at least 30% of mycoremediation procedures[11,12]. These fungi are characterized by their ability to extensively degrade lignin, hemicellulose, and cellulose. The transformation and mineralization of soil pollutants structurally similar to lignin have been successfully linked to several white-rot genera, including Bjerkandera, Irpex, Lentinula, Phanerochaete, Pleurotus, and Trametes[12−14]. In addition to WRF, several other fungal groups, such as Aspergillus, Cryptococcus, Curvularia, Drechslera, Fusarium, Lasiodiplodia, Mucor, Penicillium, Rhizopus, and Trichoderma, have been examined for their pollutant remediation capabilities[6]. Despite the extensive research on these and other fungal groups, the potential of coprophilous fungi (CF) (fungi that naturally grow in the dung of herbivores) for environmental remediation has not been extensively explored. Although CF are taxonomically diverse, spanning various phyla, they share certain ecological and physiological characteristics. Existing research on the environmental role of coprophilous fungi has primarily focused on their capacity to degrade plant remains. For example, the coprophilous fungus Podospora anserina has been studied for its lignocellulose-degrading capabilities[15]. However, the broader environmental role of CF beyond the breakdown of plant matter remains largely unexplored. Further investigations are needed to expand our understanding of coprophilous fungal diversity and their potential applications in environmental remediation. This review aims to shed light on coprophilous fungi and their potential role in soil mycoremediation.

-

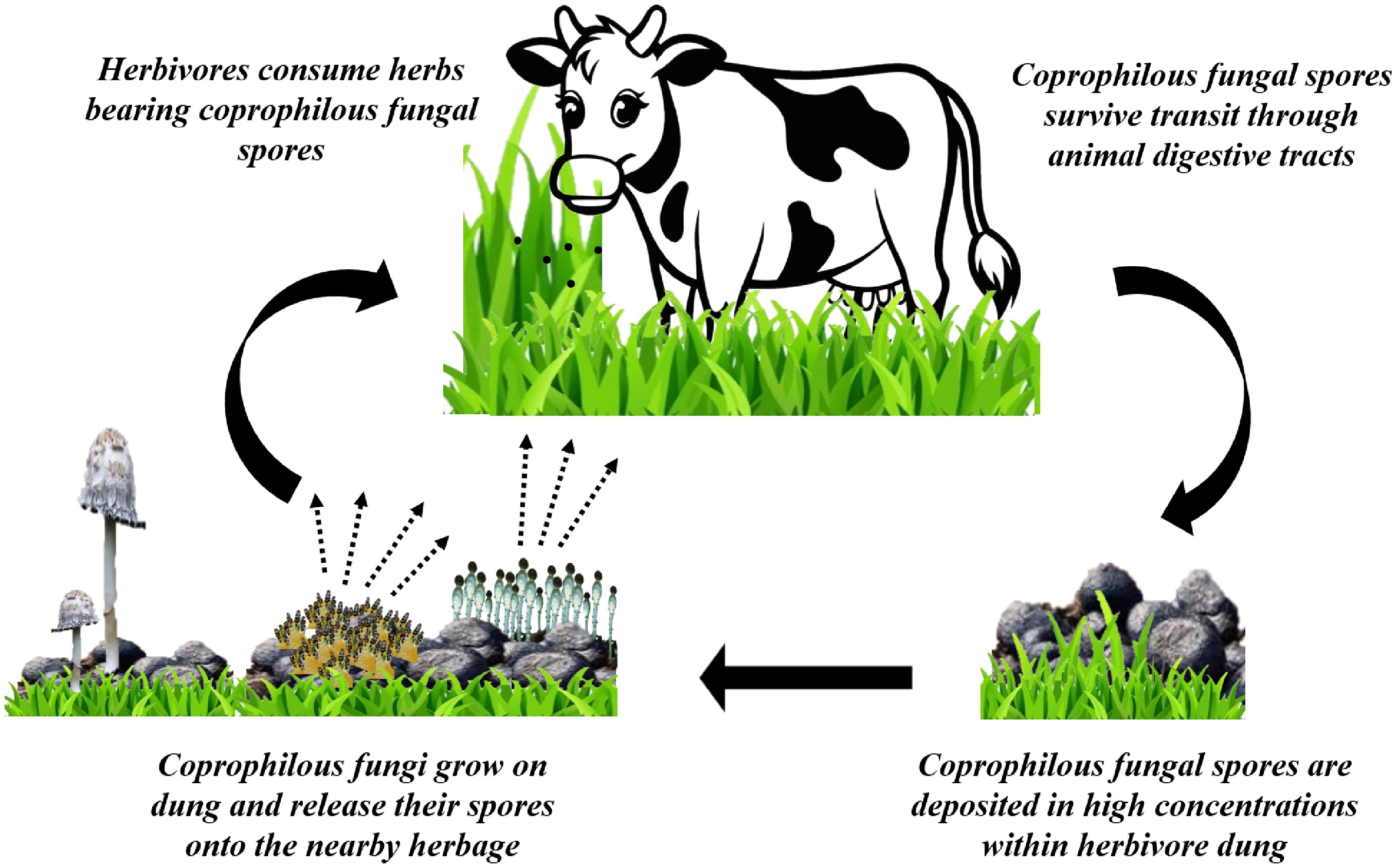

Coprophilous fungi (CF) are cosmopolitan saprophytic fungi that grow on the dung of herbivores (Fig. 2). They are divided into two types. Obligate CF must have their spores consumed by herbivores and passed through the digestive system to break their dormancy and germinate. In contrast, facultative CF can germinate without needing to pass through a herbivore's digestive tract[16,17]. Most CF belong to the obligate category[18,19]. These fungi are found in four phyla: mainly Ascomycota and Basidiomycota, as well as some Mucoromycota and Kickxellomycota[19−22]. CF diversity varies depending on the animal and geographical region, but they all play a crucial role in breaking down plant remnants in dung[23].

Figure 2.

Two CF developing on cow dung. (a) Young apothecia of Ascobolus scatigenus. (b) Young basidiocarps of Parasola misera. Photograph provided by Dr. Francisco Calaça.

Dung is an ideal, nutrient-rich substrate for various microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, and archaea. It contains the undigested remains of woody plants, grass, and herbs, making polysaccharides like cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin major constituents. The pH of dung is generally greater than 6.5, and it is rich in nitrogen, phosphorus, carbon, potassium, and other minerals, along with vitamins and growth factors. While dung can hold a significant amount of water, this capacity decreases over time[23,24].

The number of CF genera is influenced by both the animal and the ecosystem. Their spores can be dispersed by air, animals, or even through long-distance ejection[25,26]. Despite these dispersal mechanisms, the diversity of coprophilous genera is limited compared to other saprophytic fungi that grow on different organic substrates. Environmental factors, such as temperature and light periods, can significantly affect the growth and diversity of CF[21].

What distinguishes CF from other ecological groups are their specific characters and adaptations. The spores of most CF are characterized by their dark color, which is due to heavy melanin pigments that protect them from UV radiation[18,27]. However, some CF do have hyaline (clear) spores. Many CF spores also have a thick wall and a gelatinous coat, which prevents germination until these layers are softened by the animal's digestive juices[16,23].

Life cycle of CF

-

The life cycle of CF is uniquely adapted to its substrate, a process known as endocoprophilous[28]. The cycle is initiated when herbivores consume spores that are attached to the plants they eat. These spores are remarkably resilient; their thick, melanized walls provide crucial protection against the aggressive chemical and microbial environment of the digestive tract. This defense mechanism ensures their survival as they pass through the animal's gut. Upon being voided in dung, which serves as a perfect substrate, the fungi germinate and begin to grow. They rapidly produce fruiting bodies that then eject new spores onto the surrounding vegetation. The life cycle is completed when these spores are ingested by another herbivore[23,27] (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Life cycle of CF. Cow vector[94].

Interestingly, recent research has revealed a more complex picture of the CF life cycle. Some strains have demonstrated endophytism, meaning they can live harmlessly inside plants, a discovery that showcases their remarkable adaptability to different ecological niches[29−31]. Specific strains have been identified as root endophytes in grass species across various biomes, suggesting a potential ecological role in enhancing plant health and resilience. This dual existence was highlighted by Miranda and co-workers[31], who stated that two CF from the order Sordariales (Zopfiella erostrata and Cercophora caudata) can independently complete their life cycle in two distinct habitats: within the coprophilous environment and in association with the roots of a host plant. This finding challenges the traditional view of their life cycle and opens new avenues for research into their ecological functions.

Succession of CF

-

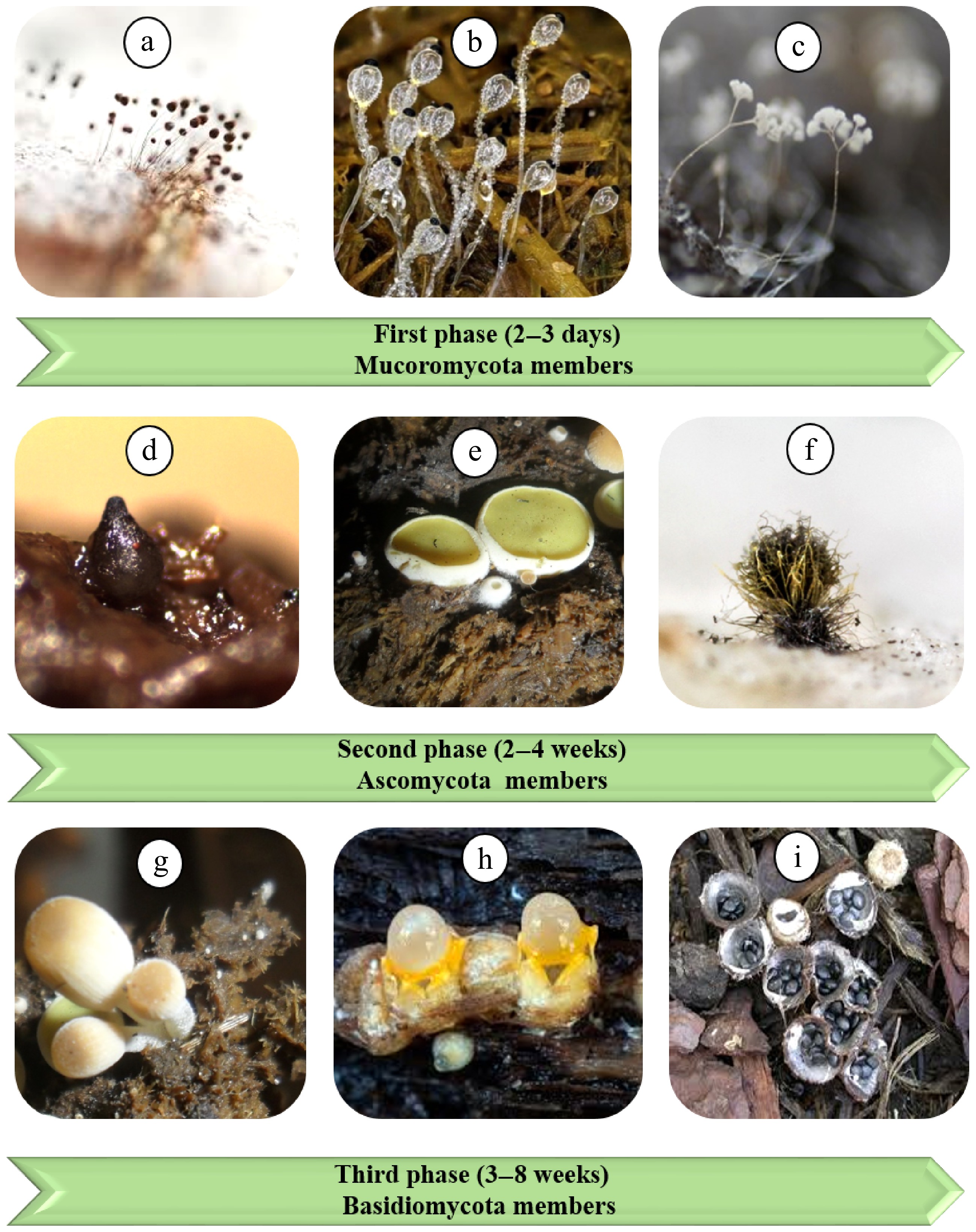

CF exhibit a consistent successional pattern on dung, regardless of the herbivore species. This process is driven by the diverse life cycles of the four fungal phyla found in this environment: Mucoromycota, Kickxellomycota, Ascomycota, and Basidiomycota (Table 1 and Fig. 4). The distinct appearances of their fruiting bodies visually represent these successional dynamics. The initial phase of succession begins rapidly. A recent survey reported the growth of yeasts and yeast-like fungi within the first 24 h, including Cryptococcus, Trichosporon, Candida, and Aureobasidium[32]. These yeasts were not previously highlighted in succession studies because they do not produce the visible fruiting bodies characteristic of filamentous fungi. Among the first filamentous fungi to produce fruiting bodies are representatives from Mucoromycota, Kickxellomycota, and Ascomycota. For example, species of Mucor, Phycomyces, and Pilobolus are known for rapidly producing abundant sporangia within two to three days, after which their output ceases. In contrast, the conidiophores of some Ascomycota, such as Aspergillus and Penicillium[16], remain active and continue to produce spores for an extended period of three to four weeks. In certain cases, fungi like Piptocephalis may emerge during the initial week of growth to parasitize members of the Mucoromycota. Additionally, if the dung is excessively wet, Arthrobotrys may arise during the first week to prey on nematode worms present in the substrate[16,21].

Table 1. Diversity of key coprophilous fungi and their taxonomic classification by successional phase.

Phase* Phylum Class CF genus Ref. Pre first phase 24 h Basidiomycota (yeasts) Tremellomycetes Cryptococcus, Trichosporon [32] Ascomycota (yeasts) Pichiomycetes Candida Dothideomycetes Aureobasidium First phase

(2−3 d)Mucoromycota Chaetocladium, Mucor, Phycomyces, Pilaira, Pilobolus, Utharomyces [16,19,21,23] Kickxellomycota Kickxella Second phase

(3−4 weeks)Ascomycota Pezizomycetes Ascobolus, Cheilymenia, Coprotus, Iodophanus, Lasiobolus, Saccobolus [16,19−23] Leotiomycetes Thelebolus Sordariomycetes Chaetomium, Cercophora, Coniochaeta, Hypocopra, Cladorrhinum, Phomatospora, Podospora, Poronia, Selinia Sordaria, Stilbella, Zygopleurage Eurotiomycetes Aspergillus, Gymnoascus, Hamigera; Paecilomyces, Talaromyces Dothideomycete Delitschia, Trichodelitschia, Sporormiella Orbiliomycetes Arthrobotrys Final phase

(3−8 weeks)Basidiomycota Agaricomycetes Bolbitius, Clitopilus, Conocybe, Coprinellus, Coprinus, Coprinopsis, Cyathus, Deconica, Panaeolus, Psathyrella, Psilocybe, Stropharia, Sphaerobolus [16,26,33,34] * Some fungal fruiting bodies could appear few days earlier or later then the mentioned time.

Figure 4.

A chronological template illustrating the sequential emergence of fruiting bodies of various coprophilous fungal genera over 8 weeks. (a) Mucor sp.[95], (b) Pilobolus roridus[96], (c) Piptocephalis sp.[97], (d) Podospra sp.*, (e) Ascobolus scatigenus*, (f) Chaetomium globosum[98], (g) Parasola misera* (h) Sphaerobolus stellatus[99], (i) Cyathus stercoreus[100]. * Photos provided by Dr. Francisco Calaça.

The second successional phase begins around the second week, following the collapse of Mucoromycota sporangiophores. This phase is marked by the appearance of Ascomycota ascocarps. It typically starts with apothecia from genera like Ascobolus and Saccobolus, followed by perithecia from genera such as Sordaria, Podospora, and Chaetomium, this pattern of succession sometimes overlap at phyla level. Ascomycota fungi have more complex fruiting bodies than Mucoromycota, which require a longer time to mature and release their spores. This phase can last from two to four weeks[22,33].

The final successional period is characterized by the development of basidiocarps from genera including Coprinus, Cyathus, Deconica, and Panaeolus[34]. However, Basidiomycota do not exclusively constitute the terminal stage of this process. It is important to note that ascomycete genera such as Coprotus and Podospora may also be present, and some members of the Gymnoascaceae can take 35–40 d to fruit[16,20,26].

Significance of dung and CF

-

Dung has been used as a readily available and economical fertilizer for centuries. It provides essential nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, which make it a highly effective and sustainable manure in agriculture. Due to its high organic matter content, dung also improves soil structure by increasing its water-holding capacity, aeration, and drainage. Additionally, the microbiota present in dung, including fungi, can help suppress plant diseases and pests[35].

CF are primarily recognized as key microorganisms in ecosystem management, as they directly facilitate fecal decomposition and contribute to the biogeochemical cycles of carbon, nitrogen, and energy[31,36]. Beyond their ecological role, CF have been highlighted as a promising source of bioactive compounds with notable antimicrobial properties[37,38]. The significant potential for antibiotic discovery from coprophilous fungi (CF) is evidenced by two key findings: the yield of antifungal antibiotics and bioactive secondary metabolites from limited previous efforts, and the mapping of numerous biosynthetic pathways in the genomes of the coprophilous fungi Podospora anserina and Sordaria macrospora[37]. CF produce a diverse array of bioactive secondary metabolites and possess a potent enzymatic arsenal capable of utilizing complex molecules[39,40]. These metabolites are actively involved in inhibiting the growth of other organisms, thereby enhancing the ecological fitness of the producer strains. For instance, petroleum ether extracts from several CF genera, such as Aspergillus spp., Chaetomium sp., Sordaria sp., and Podospora sp., have shown significant inhibitory activity against pathogenic bacteria like Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus enterobacter, Proteus mirabilis, and E. coli[38]. Furthermore, the ability of some CF to complete their life cycle as root endophytes[30,31] underscores their potential as a source of bioactive compounds, a known characteristic of endophytic fungi[41].

In paleontological and archaeological studies, dung fungal ascospores have frequently served as indicators of past herbivore populations[18,42]. Their characteristic thick, melanized walls protect them from UV light and harsh environmental conditions, allowing them to persist for thousands of years. For example, a recent study successfully extracted CF spores from sediments to identify the presence of herbivores in former ecosystems[17].

The biotechnological potential of coprophilous fungi is also significant, particularly in the production of biofuel[32,43]. A pioneering proteomic analysis of the secretome of the coprophilous fungus Doratomyces stemonitis C8 identified a broad range of enzymes involved in the degradation of cellulose, hemicellulose, pectin, lignin, and protein. The secretome of D. stemonitis C8 showed a high degree of specialization for pectin degradation, which distinguishes it from other saprophytic fungi, such as the industrially exploited Trichoderma reesei. These findings suggest a potential for increasing the efficiency of plant biomass degradation in future industrial processes like biofuel production[43]. In a related study, Makhuvele and co-workers reported that six yeast isolates from the dung of wild herbivores were capable of producing ethanol during growth on xylose[32].

-

This section explores successful investigations into the degradation capabilities of various fungal groups, including soil fungi, white-rot fungi, and coprophilous (dung) fungi. These organisms have demonstrated a promising capacity to degrade and reduce a wide range of environmental pollutants, such as toxic metals and metalloids, petrochemicals, polymers, pesticides, textile dyes, explosives, and radionuclides.

Degradation of heavy metals

-

Heavy metal pollution poses a serious global threat to human health and the environment. Metals such as copper (Cu), chromium (Cr), cadmium (Cd), mercury (Hg), iron (Fe), zinc (Zn), lead (Pb), manganese (Mn), and nickel (Ni) present significant environmental risks when they contaminate soil, water, and the atmosphere. The primary sources of this pollution are mining, smelting, processing, and other industrial activities[44]. The ability of fungi to degrade or remove certain heavy metals has been well-documented. Genera such as Mucor, Emericellopsis (= Stilbella), Coprinus, Panaeolus, and Sphaerobolus have been successfully utilized in the bioremediation of heavy metals from contaminated soil.

The genus Mucor (Mucoraceae, Mucorales, Mucoromycetes) is a cosmopolitan, fast-growing soil saprotroph with 110 documented species[45]. While most are found in soil, their ecological roles are still poorly understood[46]. For instance, a Mucor strain isolated from mine tailings, identified as M. circinelloides, demonstrated high tolerance and resistance to high concentrations of heavy metals, including Pb(II), Zn(II), Fe(III), Mn(II), and Cu(II). This strain also exhibited potent absorption, with minimum inhibitory concentrations resulting in the uptake of 79.5% of Fe(III), 44.1% of Mn(II), 62.5% of Cu(II), 56.5% of Zn(II), and 85.5% of Pb(II) from an initial concentration of 20 mg/L[47]. A synergistic microbial remediation study further showed that M. circinelloides, alongside Actinomucor sp. and Mortierella sp., effectively reduced heavy metal immobilization by up to 74.98% (Zn), 85.29% (Pb), and 79.41% (Mn). This combined approach also significantly shortened the remediation period and improved the poor habitat of the mine tailings[44].

Emericellopsis (= Stilbella), a cosmopolitan genus that can grow on dung, has been placed within the family Bionectriaceae (Hypocreales) and includes 50 described species[45]. Its bioremediation potential has been demonstrated through the non-enzymatic bio-oxidation of superoxide. Manganese (Mn) oxides are highly reactive minerals in the environment that control the bioavailability of various metals, carbon, and nutrients. Emericellopsis aciculosa (= Stilbella aciculosa), a filamentous fungus isolated from a water remediation system at a coal mine, was studied for its ability to remove manganese from soil. E. aciculosa was found to oxidize manganese by producing extracellular superoxide during its cell development[48].

The white-rot genus Coprinus (Agaricaceae, Agaricales, Agaricomycetes) comprises 140 described species[45]. Coprinus comatus shows great potential for remediation due to its ability to release laccase. This fungus has proven effective at absorbing heavy metals such as Cu, Cd, Hg, and Ni[49−52]. Coprinus comatus also has the potential to serve as a mercury bioextractor and a bioindicator of soil contamination. A study showed that the mercury content in the caps and stipes of C. comatus from contaminated soils positively correlated with soil contamination levels, indicating its sensitivity and potential for both bioindication and bioremediation[49]. In 2018, Wang et al.[50] investigated the co-remediation potential of C. comatus and Pleurotus eryngii on soil co-contaminated with cadmium (Cd) and endosulfan. Their findings revealed that the mushroom fruiting bodies accumulated Cd at concentrations of 1.83–3.06 mg/kg, while the removal rates of endosulfan exceeded 87%. This study underscored the significance of co-remediation for multi-contaminated soil. Furthermore, an investigation into the effects of C. comatus on the biochemical properties and lettuce growth in soil co-contaminated with copper and naphthalene found that copper accumulation in the fungal body positively correlated with increased metal loading. The study also reported high naphthalene removal ratios, ranging from 96.00% to 97.16%, depending on contaminant levels[51]. The combined application of Coprinus comatus with Serratia sp. and/or Enterobacter sp. has also been investigated for the detoxification of nickel and fluoranthene from contaminated soil. The results demonstrated that co-inoculation with Serratia sp. and Enterobacter sp. was more effective than solitary inoculation in enhancing fungal biomass, Ni accumulation, and fluoranthene dissipation[52].

The majority of Panaeolus (Typhulaceae, Agaricales, Agaricomycetes) species are coprophilous, though some have been found in wood. The genus currently includes 80 legitimate species[45]. Panaeolus could play a significant environmental role in removing heavy metals. A recent study explored the use of P. papilionaceus biomass as a biosorbent to remove Pb2+ ions from an aquatic medium. The optimal operating conditions were identified as pH 4.5, a temperature of 25 °C, a contact time of 24 h, and an initial Pb2+ concentration. The Langmuir model indicated a maximum biosorption capacity of 31.2 mg/g. Thermodynamic studies confirmed that Pb2+ ion biosorption into the fungal biomass was a spontaneous and endothermic process[53].

Sphaerobolus is a white-rot fungus (Sphaerobolaceae, Geastrales, Agaricomycetes) with six documented species[45]. It is typically found in temperate climates on forest floors, dung, and wood mulches[54,55]. A study demonstrated that pre-treatment of contaminated soil with S. stellatus, followed by high-temperature combustion, was capable of removing lead while also degrading 10% of the soil's organic carbon over a 6-month period[56].

Degradation of petroleum hydrocarbons

-

The effective elimination of petroleum hydrocarbon products has been successfully demonstrated by several fungal genera, including Phycomyces, Mucor, Saccobolus, Coprinus, Stropharia, Sphaerobolus, and Coniochaeta.

Phycomyces belongs to the Phycomycetaceae (Mucorales, Mucoromycetes) and has three reported species[45]. As a saprophytic fungus, Phycomyces is globally distributed in humid climates, and its spores are occasionally found in animal feces from moist woodlands[57]. Studies have shown that both Phycomyces sp. and Mucor sp. can remove aromatic hydrocarbons from soil[58]. The lignocellulolytic potential recently demonstrated by Mucor circinelloides and Phycomyces blakesleeanus may explain their capacity to break down aromatic hydrocarbons[59].

Saccobolus (Ascobolaceae, Pezizales, Pezizomycetes) is a widely distributed coprophilous genus with 45 documented species[45]. The ability of Saccobolus saccoboloides to decompose various wastes, including filter paper, newspaper, cardboard, sawdust, and wood shavings, was examined. After 8 d of cultivation in agitated synthetic liquid media, all paper and cardboard samples showed significant weight loss and complete cellular separation. However, S. saccoboloides was unable to decompose wood waste[60].

Species of the genus Stropharia (Strophariaceae, Agaricales, Agaricomycetes) are commonly found in woods, grasslands, compost piles, and dung. The genus includes 65 accepted species[45], and can function as a biocontrol agent against nematodes[61]. A study on the pre-treatment of contaminated soils with Sphaerobolus stellatus and Stropharia rugosoannulata, followed by high-temperature combustion, was conducted. The results showed that S. stellatus degraded 20% of the soil organic carbon in 6 months, while S. rugosoannulata degraded 10%[56].

The genus Coniochaeta (Coniochaetaceae, Coniochaetales, Sordariomycetes) comprises 100 species. Coniochaeta spp. and their Lecythophora anamorphs are found in diverse habitats, including herbivore dung, wood pulp, tree bark, water, soil, and leaf litter, and are infrequently found on non-woody host plants like Gramineae[45,62]. A Coniochaeta sp. strain demonstrated a capacity to decompose total petroleum hydrocarbons (TPHs) in contaminated soil. In soil microcosm treatments, the fungus successfully degraded 84% of the TPHs after 60 d of inoculation[63]. Furthermore, Coprinus spp. have been shown to degrade and reduce fluoranthene and naphthalene from contaminated soil[51,52].

Degradation of explosive pollutants

-

Soil pollution from explosives, particularly TNT (2,4,6-trinitrotoluene), is a serious consequence of armed conflicts. TNT is the most common explosive contaminant, found in approximately 80% of soil samples contaminated with explosives. TNT is highly toxic to a wide range of organisms and severely disrupts the natural soil environment. Several fungal genera have demonstrated the capacity to remediate these pollutants, including Podospora, Mucor, Coprinus, Aspergillus, and Stropharia.

The genus Podospora is a cosmopolitan coprophilous fungus belonging to the Podosporaceae (Sordariales, Sordariomycetes). With 100 documented species, it is occasionally isolated from soil and plants as an endophyte[45,64]. As a relatively late-stage ascomycete degrader, P. anserina fructifies after the succession of many other coprophilous organisms, suggesting it is particularly adapted to exploiting the more resistant components of lignocellulose. In 2008, the sequencing of the P. anserina genome led to the discovery of a wide range of enzymes that target plant carbohydrates, especially lignin. A few years later, enzymes such as N-acetyltransferase were reported for their role in detoxifying certain environmental pollutants. Podospora anserina produces two N-acetyltransferase (NAT) enzymes that reduce the toxicity of various substances, including xenobiotic pollutants and explosives[65,66].

Studies have also unveiled the effectiveness of other fungi[67,68]. Mucor mucedo DSM810 and Coprinus comatus TM6 reduced the level of TNT by 95% and 82%, respectively, after only 6 d of incubation[67]. In another study, Mucor sp. T1-1 and Aspergillus niger N2-2, isolated from a polluted area near military grounds and industrial wastewater, were evaluated for TNT remediation under laboratory and field conditions. The findings revealed that both fungi could successfully degrade and reduce TNT levels in the tested soil[68].

A screening of 91 fungal strains by Scheibner et al.[69] aimed to verify the ability of selected fungi to metabolize and mineralize TNT. The results showed that within 64 d, Stropharia rugosoannulata DSM11372 mineralized 36% of the initial [14C] TNT (100 µM, corresponding to 4.75 µCi/L) to 14CO2.

Degradation of plastics and other polymers

-

The rapid growth in plastics manufacturing, including products like polycaprolactone (PCL), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), and polypropylene (PP), has led to significant global pollution. This is a major challenge because plastics are extremely resistant to environmental breakdown, persisting for decades[70]. Despite this, some studies have revealed the promising role of fungi in remediating polymers, with successful examples including Chaetomium, Coniochaeta, and Mucor.

The genus Chaetomium (Chaetomiaceae, Sordariales, Sordariomycetes) is a common fungal taxon with 359 described species[44]. Chaetomium has significant degradation potential by secreting numerous enzymes[71] that break down and absorb polymeric materials, such as plastics. Chaetomium globosum, the most prevalent and diverse species, frequently contributes to the breakdown of plant remnants, paper, and other cellulosic materials[72]. The biodegradation of PCL and PVC films by C. globosum (ATCC 16021) has been examined. A notable decrease in mass was observed in the PCL films. Microbial adherence, the initial stage of breakdown, was observed on both the hydrophilic PCL and hydrophobic PVC polymers[73].

Polypropylene (PP), a thermoplastic polymer, is a significant component in the plastics industry, accounting for 16% of global plastic packaging materials[74]. The degradation of PP by Coniochaeta hoffmannii has also been reported. In a study where C. hoffmannii was grown on a commercial PP textile for 17 d and 2 months, the fungus showed extensive growth across the synthetic fibers, utilizing pure PP as its sole carbon source[75].

Additionally, a Mucor sp. isolated from soil contaminated with PVC resin was cultivated in a medium where PVC film was the sole carbon source. The fungus gained biomass from the PVC, and the films showed observable changes, which were further supported by infrared spectra[76].

Degradation of synthetic textile dyes

-

The successful removal of both natural and synthetic textile dyes has been achieved using several fungal genera, including Cyathus, Gymnoascus, Coprinus, and Chaetomium.

Cyathus species are white-rot fungi found on decomposing plant debris and dung. The genus contains 100 species and is classified in the Nidulariaceae (Agaricales, Agaricomycetes)[45]. A study on C. bulleri reported the production of high levels of laccase on solid wheat bran[77]. This fungus was effective at oxidizing veratryl alcohol, reactive blue 21, and textile effluent without the need for external mediators. When cultivated on wheat bran, the fungus produced eight laccase isozymes, which were more effective at decolorizing and degrading textile effluent than laccases from basal salt cultivation. These isoforms also reduced phytotoxicity by over 95%. Another study explored the biodegradation of 14C-labeled lignin in kenaf by 12 Cyathus species[78]. Three species (C. palliduis, C. africanus, and C. berkeleyanus) were identified as exhibiting the fastest delignification rates. Furthermore, an investigation into the decolorization of reactive azo and acid dyes using C. bulleri culture filtrate and purified laccase found that the enzyme showed high specific activity and was sequence-identical to laccases from various white-rot fungi. The highest catalytic efficiency was observed on guaiacol and ABTS, with 50% decolorization achieved in 0.5–5.4 d[79].

Gymnoascus is classified in the Gymnoascaceae (Onygenales, Eurotiomycetes), and 26 species have been documented[45]. While some Gymnoascus species originate from plant debris, dung, and soil, they can also be isolated from materials like nails, feathers, or hair[80]. A study reported the promising role of a Gymnoascus strain in the degradation of natural and synthetic dyes[81]. The study specifically examined the impact of Gymnoascus arxii on woolen textiles dyed with natural and synthetic dyes. The strain caused severe mechanical deterioration, with raw fabric being the most damaged. The only fabrics that survived on the enriched medium were yellow or weld-dyed textiles. The study concluded that enriching the culture medium with nutrients could prevent this deterioration.

Coprinus plicatilis was found to be 99% effective at decolorizing the textile dye reactive blue 19[82], a result linked to its laccase enzyme. Recently, C. comatus was shown to be 38.66% effective in the breakdown of lignin in maize stalks, with laccase, xylanase, and carboxymethyl cellulase all contributing to the process[83].

A new fungal laccase produced by a Chaetomium sp. isolated from arid soil was purified and characterized to determine its ability to remove dyes. This enzyme showed the capacity to decolorize various dyes, with or without 1-hydroxy-benzotriazole as a redox mediator, suggesting its potential for bioremediation and other industrial applications[84].

Degradation of plastics and other polymers

-

The potential for degrading herbicides and pesticides has been demonstrated by several fungal genera, including Pilobolus, Podospora, Sordaria, and Coprinus.

The genus Pilobolus (Pilobolaceae, Mucorales, Mucoromycetes) is an obligate dung fungus with only eight species[45,85]. Methyl parathion (MP), a commonly used pesticide, is a neurotoxic chemical classified by the WHO as an extremely hazardous insecticide due to its negative effects on both the environment and human health[86]. In microsystems containing corn crops contaminated with MP, a Pilobolus sp. inoculum showed an outstanding capacity to remove the pesticide, effectively eliminating it in 80% of the microsystems. Pilobolus sp. also positively influenced the physiological processes of 20% of the corn plants. Following inoculation, MP was almost completely absent from the corn plant leaves. Additionally, notable differences (9%) were observed in the concentrations of carotenes and chlorophyll (A and B) between the MP-exposed plants and the control group. The significant decrease of MP in the soil and corn plants is interpreted as a result of its degradation. This conclusion is supported by the low MP concentration found in samples extracted from the Pilobolus inoculum in the microsystems[87].

Podospora anserina was able to detoxify the extremely toxic pesticide residue 3,4-dichloroaniline (3,4-DCA) in experimentally contaminated soil samples through its arylamine N-acetyltransferase 2 (NAT2) enzyme[88]. The ability of Sordaria spp. to break down the two herbicides metribuzin and linuron was also explored, with some Sordaria species showing a reduction in herbicide levels[89]. Furthermore, while Coprinus comatus was shown to degrade the insecticide and acaricide endosulfan on its own, its degrading capacity was enhanced through co-cultivation with Pleurotus eryngii[50].

-

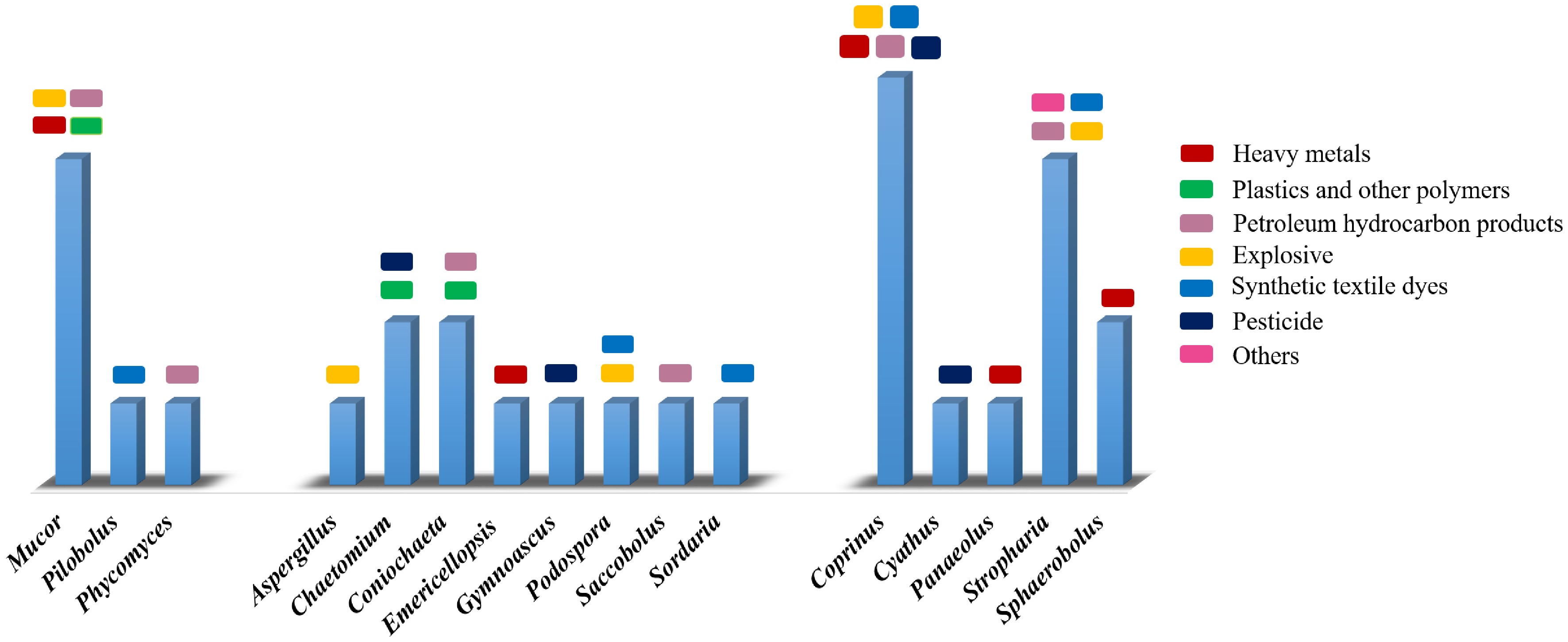

Sixteen fungal genera across three phyla have emerged as promising candidates for mycoremediation, revealing considerable potential for degrading a wide range of environmental contaminants. These include: Mucor, Pilobolus, and Phycomyces (Mucoromycota); Aspergillus, Chaetomium, Coniochaeta, Emericellopsis (= Stilbella), Gymnoascus, Podospora, Saccobolus, and Sordaria (Ascomycota); Coprinus, Cyathus, Panaeolus, Sphaerobolus, and Stropharia (Basidiomycota). The remediation capacities of these fungi are further detailed in Table 2. The contribution of these three fungal phyla to the degradation of plant remains has been documented[59]. Recent genome analyses have further shown that Mucoromycota are significantly involved in plant biomass degradation, a role previously attributed primarily to the Ascomycota and Basidiomycota.

Table 2. An overview of the 16 fungal genera and their roles in mycoremediation of recalcitrant pollutants.

Fungal genera Pollutants Ref. Mucor mucedo DSM810 TNT [44,47,67,68,76] Mucor circinelloides Heavy metals: Pb (II), Zn (II), Fe (III), Mn (II), and Cu (II) Mucor sp. Thermoplastic Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) Pilobolus sp. Parathion methyl [87] Phycomyces sp. Petroleum hydrocarbons or other organic chemicals [58,59] Saccobolus saccoboloides Organic solid wastes [60] Chaetomium globosum ATCC16021 PCL and PVC (Polycaprolactone); Cellulosic materials and dyes [73,84] Coniochaeta hoffmannii Polypropylene [63,75] Coniochaeta sp. Petroleum hydrocarbons Podospora anserine Explosives and xenobiotic pollutants [65,66] Sordaria superba, Herbicides [89] Emericellopsis aciculosa Oxidize Mn [48] Gymnoascus arxii Natural and synthetic textiles dyes [81] Aspergillus niger 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT) [68] Coprinus comatus Heavy metals such as Cu, Cd, Ni, Hg, and Pb [49−52,67,82] Organic pollutants: naphthalene, fluoranthene, and endosulfan Coprinus plicatilis The textile dye remazol reactive blue 19 Cyathus bulleri Textile effluent [78,79] Panaeolus papilionaceus Remove Pb2+ ions from aquatic medium. [53] Stropharia rugosoannulata TNT, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), carbamazepine, chlorinated phenols, dibenzo-p-dioxins, furans and other organic matters. [56,69,90−92] Sphaerobolus stellatus Organic matters [56] Members of the Mucoromycota, such as Mucor, Pilobolus, and Phycomyces, are among the first to appear in coprophilous fungal succession, typically within two to three days. Notably, Mucor has demonstrated a broad spectrum of degrading activities, effectively remediating a diverse range of contaminants, including the explosive TNT[68], the plastic PVC[76], heavy metals like Pb, Zn, Fe, Mn, Cu[44,47], various petroleum hydrocarbons, and other organic chemicals[58,59]. Similarly, a Pilobolus sp. inoculum successfully degraded the pesticide methyl parathion in a corn plantation and enhanced the physiological processes of the corn plants[87]. Phycomyces sp. has also shown the ability to remove aromatic hydrocarbons from soil[58,59].

Ascomycota members, which fruit in the second phase of fungal succession on dung, have demonstrated significant degrading capabilities. Eight genera, including Saccobolus, Chaetomium, Coniochaeta, Podospora, Sordaria, Emericellopsis, Gymnoascus, and Aspergillus, have been studied for their ability to degrade various contaminants. Saccobolus has effectively degraded various paper wastes[60]. Chaetomium has shown potential for remediating a wide range of pollutants, including cellulosic materials, polymers like PCL and PVC[73], and dyes[84]. Petroleum hydrocarbon products and polypropylene have been successfully broken down by Coniochaeta spp.[63,75]. Podospora was able to detoxify the highly toxic pesticide residue 3,4-dichloroaniline (3,4-DCA)[88] and has also been found to degrade explosive compounds[65,66]. A Sordaria sp. degraded the herbicides metribuzin and linuron[89], while Emericellopsis displayed its remediation potential by oxidizing manganese in soil[48]. Finally, Aspergillus was successfully used to reduce TNT levels in a contaminated area[68].

Basidiomycota members appear in the third and final stage of fungal succession. Certain macrofungi from this phylum are known to successfully absorb various metallic elements and metalloids from the soil and store them in their fruiting bodies. Five genera: Coprinus, Cyathus, Panaeolus, Stropharia, and Sphaerobolus have shown potent remediation abilities for a variety of contaminants. Coprinus, in particular, exhibits a broad range of degrading and detoxifying abilities due to its production of laccase. It has proven effective at absorbing heavy metals such as Cu, Cd, Ni, Hg, and Pb[49−52], and at breaking down organic pollutants like endosulfan, fluoranthene, naphthalene[51,52], and the explosive TNT[67]. Coprinus also effectively decolorized the textile dye reactive blue 19[82]. Cyathus has revealed the ability to oxidize veratryl alcohol, reactive blue 21, and textile effluent[78], as well as the capacity to decolorize guaiacol and ABTS[79]. The potential of Panaeolus for removing lead has also been documented[53]. Furthermore, some Stropharia species have shown promising efficacy for remediating several contaminants, including TNT[69], polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)[56], carbamazepine, chlorinated phenols, dibenzo-p-dioxins, and furans[90−92]. Sphaerobolus has been shown to break down various soil organic carbons, including heavy metals (Pb) and PAHs[56].

The comprehensive analysis of these fungi reveals that three genera: Coprinus and Stropharia (both from Basidiomycota), and Mucor (from Mucoromycota) exhibit a broad capacity for remediating a wide range of recalcitrant pollutants (Fig. 5). Coprinus demonstrated the highest remediation capacity, effectively removing five distinct types of contaminants: heavy metals, insecticides, PAHs, TNT, and synthetic textile dyes. Stropharia successfully detoxified four types of contaminants: TNT, PAHs, pesticides, and other industrial effluents. Similarly, Mucor remediated four categories of contaminants: TNT, heavy metals, plastics/polymers, and petroleum hydrocarbon products.

Figure 5.

A histogram illustrating the number of distinct recalcitrant pollutants degraded by each of the 16 fungal genera reported. Data sources Mucor[47,58,67,76], Pilobolus[87], Phycomyces[58], Saccobolus[60], Chaetomium[73,84], Coniochaeta[63,75], Podospora[65,66], Sordaria[89], Emericellopsis[48], Gymnoascus[81], Aspergillus[68], Coprinus[49,50,52,67,82], Cyathus[78], Panaeolus[53], Stropharia[56,69,90–92], and Sphaerobolus[56].

The composition of the dung microbiome is uniquely shaped by both the animal species and their dietary intake. A recent study[24] screened the dung of five different herbivores and identified Ascomycota as the most prevalent fungal phylum, while Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes were the most common bacterial phyla. This highlights dung as a unique substrate that naturally contains a diverse consortium of microbial life, including fungi and bacteria. The natural co-existence of these microbial groups in dung suggests a potential for synergistic remediation effects, a concept supported by numerous studies on co-cultivation. For instance, Tang and co-workers investigated a sustainable technique for detoxifying nickel-fluoranthene co-contaminated soil by co-cultivating Coprinus comatus with Serratia sp. FFC5 and/or Enterobacter sp. E2. Their findings showed that the bacterial inoculation significantly enhanced the detoxification effects of C. comatus in the co-contaminated soil[52]. Similarly, the absorption of various heavy metals by C. comatus from contaminated soil was increased when the fungus was co-inoculated with bacteria[93]. The remediation efficacy of C. comatus on soil co-contaminated with endosulfan and cadmium was also accelerated when the fungus was co-cultivated with Pleurotus eryngii[50].

This natural and effective approach to remediating persistent pollutants is promising. Dung provides an ideal substrate for several fungal genera, such as Coprinus, Stropharia, and Mucor, all of which have demonstrated significant degradation capabilities. The remarkable fungal diversity within dung, however, is specific to the host animal. Recent research has shown that horse dung is rich in Mucoromycota and Verrucomicrobiota, whereas rabbit dung is characterized by a high concentration of Proteobacteria[24]. Conversely, donkey dung exhibits a significant presence of Basidiomycota[21]. This natural prevalence of specific species within different dungs suggests a targeted role in pollutant remediation. For example, the dominance of macrofungi like Coprinus spp. in donkey dung may indicate its specific potential for remediating heavy metals from soil.

The environmental significance of dung and CF

-

CF, which naturally appear on herbivore dung, have been identified as playing a significant environmental role. The present comprehensive research has highlighted 16 fungal genera that demonstrate a remarkable ability to degrade pollutants in contaminated soil. Since dung is deposited directly onto the soil, these fungi inherently contribute to the natural degradation and cleanup of plant biomass. Moreover, they may also silently assist in the remediation of various contaminants. This discovery underscores the promising role of CF in large-scale mycoremediation efforts. Because these fungi naturally grow and produce fruiting bodies on dung, they represent an excellent and readily available source for bioremediation agents.

Certain genera, such as Mucor, Coprinus, and Stropharia, have notably exhibited a broad spectrum of activity in remediating various recalcitrant contaminants. Given the documented variation in coprophilous fungal diversity based on host animal and geographical region, the isolation of novel species from different dungs is highly probable. To fully understand this potential, several critical questions require further investigation: Do other coprophilous fungal strains possess decomposing potential similar to that of white-rot fungi? Does the fungal community within a dung pellet provide a synergistic effect in contaminant degradation? What is the overall remediation potential of these fungi in a natural setting? Therefore, continued research into coprophilous fungi and their capacity to remove contaminants from soil is imperative.

Rethinking dung's role: beyond traditional manure

-

The conventional use of dung as a natural manure deserves to be re-evaluated in light of recent findings. The discovery that some coprophilous fungi can continue their life cycle as endophytic fungi opens a new avenue for developing novel biofertilizers. This dual capacity suggests that CF could be an ideal source for biofertilizers in addition to their effective degrading capabilities. Given their profound ecological role in pollutant remediation and their potential to enhance plant physiological processes, these fungi deserve more attention and further investigation.

-

CF are a unique group of saprophytes that thrive on herbivore dung, where they develop their characteristic fruiting bodies. These fungi emerge from four phyla: primarily Ascomycota and Basidiomycota, along with some Mucoromycota and Kickxellomycota. This review has demonstrated the significant mycoremediation potential of these fungi, with 16 genera documented to have potent abilities to degrade various persistent contaminants, including toxic metals, metalloids, petrochemicals, polymers, pesticides, textile dyes, explosives, and radionuclides. Notably, Mucor, Coprinus, and Stropharia have revealed an exceptionally broad remediation spectrum. This review sheds light on the promising environmental capabilities of CF and suggests their potential as elite candidates for novel biofertilizers. Their ability to serve as root endophytes and their natural co-existence with a diverse microbiome in dung further enhances their appeal. Clearly, CF deserve more extensive investigation to fully unlock their profound environmental and agricultural benefits.

-

Khairalla A confirms sole responsibility for the following: study conception and design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of results, and manuscript preparation.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

The author is grateful to Dr. Francisco Calaça for his generous supply of some photos of coprophilous fungi. Dedicated to: Dr. Awad Hassan Mohamed Ahmed (1938–2024), a Sudanese mycologist (PhD-Cambridge 1977).

-

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Khairalla A. 2025. Promising role of coprophilous fungi in mycoremediation. Studies in Fungi 10: e033 doi: 10.48130/sif-0025-0030

Promising role of coprophilous fungi in mycoremediation

- Received: 11 July 2025

- Revised: 24 October 2025

- Accepted: 28 October 2025

- Published online: 31 December 2025

Abstract: Environmental pollution from recalcitrant pollutants is a growing global concern, and mycoremediation offers a promising, sustainable solution. This review introduces coprophilous fungi (CF) as a new area of potential. These saprophytic fungi, which grow on herbivore dung, primarily belong to the Ascomycota and Basidiomycota, with some representatives from Mucoromycota and Kickxellomycota. Although their capacity to produce antimicrobial compounds has recently been highlighted, the recognized environmental importance of CF has traditionally been confined to the deterioration of plant residues. However, this review demonstrates that the remediation potential of these fungi is far broader. Herein, 16 fungal genera: Aspergillus, Chaetomium, Coniochaeta, Coprinus, Cyathus, Emericellopsis, Gymnoascus, Mucor, Panaeolus, Phycomyces, Pilobolus, Podospora, Saccobolus, Sordaria, Sphaerobolus, and Stropharia have been documented to possess potent abilities to degrade a wide range of persistent contaminants, including toxic metals, petrochemicals, polymers, pesticides, textile dyes, and explosives. Notably, three genera, Mucor, Coprinus, and Stropharia, exhibited a particularly wide remediation spectrum. This research suggests that the environmental significance of coprophilous fungi extends far beyond simple plant decomposition. Given their natural diversity and presence in dung, these fungi represent an invaluable, untapped resource for bioremediation, biocontrol, and biofertilizer applications. Therefore, further investigation into coprophilous fungi is recommended to fully explore their promising roles in both the environmental and agricultural sectors.

-

Key words:

- Bioremediation /

- Coprinus /

- Dung fungi /

- Mucor /

- Recalcitrant pollutants /

- Stropharia /

- Heavy metals /

- Polymers /

- Pesticides /

- Explosives.