-

Nuclear energy is a clean and low-carbon source of energy, contributing 17% to the global power generation on average[1]. The rapid expansion of nuclear energy has led to a growing demand for uranium resources, which are essential to ensure sustainable power generation and a secure nuclear fuel supply[2]. As the main fuel in nuclear fission, uranium is consistently found in both oceanic and terrestrial environments[3]. Global terrestrial uranium deposits are limited to approximately 4.5 million tons, whereas the oceans hold an enormous inventory exceeding 4.5 billion tons—three orders of magnitude greater[4]. The limited availability of uranium in terrestrial ores necessitates the exploration of alternative sources, such as seawater and uranium-rich wastewater, to ensure energy security and environmental sustainability[5].

Liquid radioactive waste is generated from uranium ore mining, nuclear power plant (NPP) operations[6], decommissioned tailings ponds[7], and spent fuel reprocessing, which pose a huge threat to environmental safety and human health[8]. As a toxic and highly mobile radioactive element, uranium can readily migrate through subsurface geological media. Excessive human ingestion of uranium leads to severe health risks such as neurotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, reproductive toxicity, ototoxicity, nephrotoxicity, and pulmonary toxicity[9]. Therefore, developing various methods for the removal and extraction of uranium from uranium-containing wastewater and seawater is highly urgent.

In the natural environment, uranium primarily exists in two oxidation states: the hexavalent uranyl ions (U(VI), UO22+), which are highly soluble and mobile, and the tetravalent form (U(IV)), which is generally insoluble and immobile[10]. According to the standard reduction potentials (E0U(VI)/U(V) = −0.135 V, E0U(VI)/U(IV) = 0.070 V)[11], the reduction of U(VI) to U(IV) by two electrons is thermodynamically more favorable than its reduction to U(V) by one electron. The reduction of U(VI) to insoluble U(IV) is widely recognized as an environmentally friendly and sustainable strategy for uranyl recovery. Building on this principle, various technologies, including adsorption[12], photocatalysis[13], and electrochemical[14] approaches, have been developed to extract uranyl from uranium-containing wastewater and seawater, many of which rely on the reductive conversion of U(VI) to U(IV). Among various approaches, electrochemical methods have garnered significant attention, resulting in a growing body of literature focused on diverse electrochemical approaches for uranyl extraction. For instance, Wang et al.[15] provided a comprehensive overview of electrocatalytic, photocatalytic, and piezocatalytic processes for the removal of organic pollutants and metal/radionuclide ions from environmental media. Tauk et al.[16] reviewed the selective removal of various ions, including lithium, copper, arsenic, uranium, phosphate, nitrate, and sulfate from mixed salt solutions via the electro-sorption method, providing valuable insights into the underlying mechanisms and key operational parameters.

However, to date, no comprehensive review has systematically examined the electrode materials, fundamental principles, and mechanisms involved in the electrochemical removal of uranyl from aqueous systems. In this review, an in-depth summary of recent advances in the development of various types of electrode materials for the selective extraction and removal of uranyl from fluoride-rich nuclear wastewater, mine wastewater, and seawater via electro-adsorption, electrocatalysis, and photo-electrocatalysis technologies are provided. We first outline commonly used electrode materials and discuss the advantages, limitations, and fabrication strategies of both powder-based and self-supporting electrodes. Subsequently, the fundamental principles, experimental configurations, prevalent electrode materials, and mechanisms underlying uranyl extraction via electro-adsorption, electrocatalysis, and photo-electro-catalysis method are systematically analyzed. Furthermore, the sources, characteristics, and challenges associated with fluoride-rich wastewater, mining wastewater, and seawater are discussed, along with the application potential of electrochemical techniques for their remediation. Finally, common characterization methods for uranium-containing products are summarized to provide a reference for future research and technological development in this field.

-

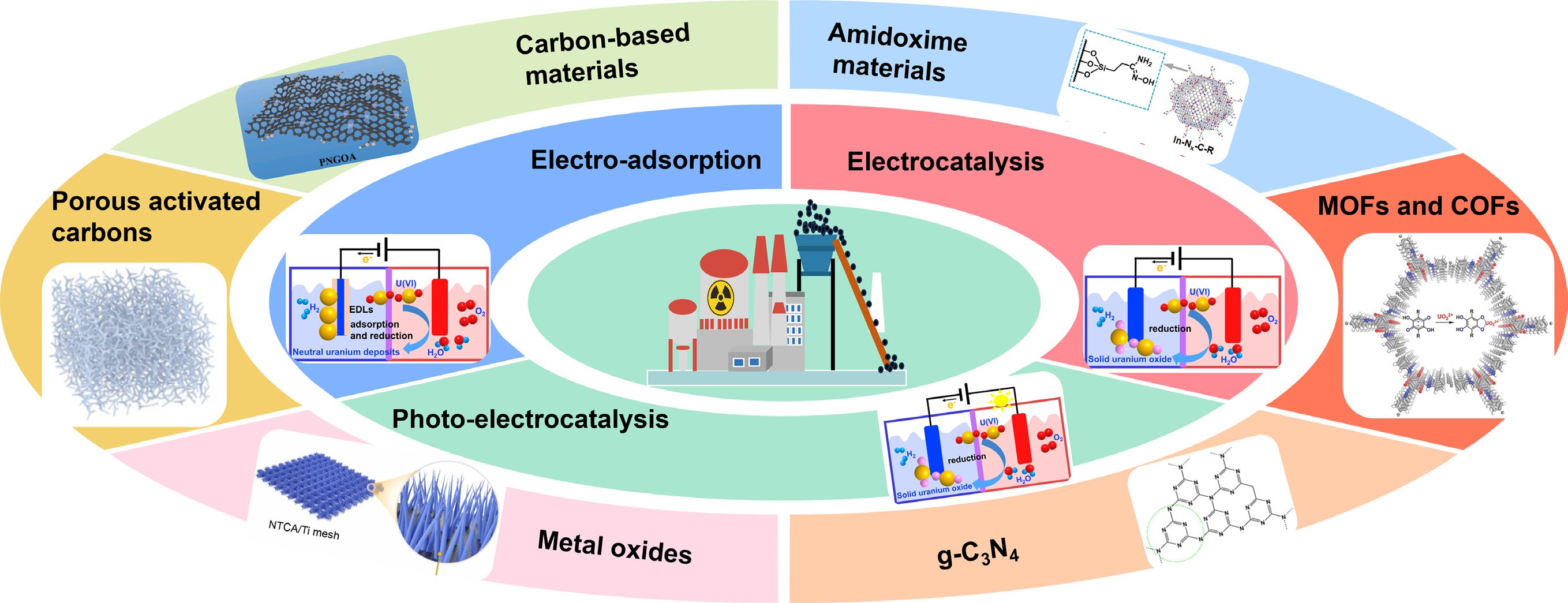

The performance of electrochemical uranyl removal may be affected by the applied voltage, pore size, and surface area of the electrode material, the ionic strength and pH value of the solution, and competing ions, reaction flow rate, and contact time[17]. The effectiveness of uranyl extraction using electrochemical methods is fundamentally determined by the characteristics of the designed electrode materials. The electrode materials employed for uranyl removal primarily comprise inorganic materials such as metal oxides/sulfides/hydroxides[18], transition metal carbides and carbonitrides (MXenes)[19], along with organic polymers, including metal organic frameworks (MOFs) and covalent organic frameworks (COFs)[20], supramolecular organic framework (SOF)[21], and various carbon-based materials[22,23] (Fig. 1). The molybdenum disulfide/graphene oxide (MoS2/GO) heterojunction achieved a removal efficiency of 97.1% at pH 5.0, at an applied potential of 1.2 V, which is significantly higher than that of MoS2 (73.6%), and GO (41.4%), respectively[18]. The WO3/C composite electrodes, fabricated by the integration of WO3 and carbon, exhibited an impressive uranyl electro-sorption capacity of 449.9 mg/g under an applied potential of 1.2 V[24]. Inorganic materials typically have high catalytic activity and tunable metal valence, but are hampered by limited conductivity and stability. By contrast, carbon-based materials offer excellent electron transport, high surface area, and high stability, yet their intrinsic catalytic activity and selectivity are insufficient without heteroatom doping or hybridization with inorganic components.

Zhang et al.[19] designed amidoxime-functionalized Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets by diazonium salt grafting, achieving the uranyl absorption capacity of 626 mg/g. However, the performance of MXenes in uranyl extraction from aqueous systems is often constrained by their limited selectivity, propensity to agglomerate, and low specific surface area. Therefore, enhancing the extraction capacity of MXenes requires their integration with porous materials or organic ligands to improve structural stability and active site accessibility.

Porous organic polymers (POPs) are a class of porous materials constructed from functional organic linkers, featuring exceptional chemical stability, structural tunability, diverse functionalities, and large surface areas[25]. MOFs possess abundant active sites and tunable pore structures, making them promising candidate materials for the selective capture of uranyl ions[26]. The carbonized MOF-199@polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP)/carbon nanotube (CNT) electrode exhibited an electro-adsorption capacity of 410.3 mg/g and an extraction efficiency of 95.2%[27]. At present, most reported COFs with intrinsic porosity and ordered framework for uranyl extraction are primarily constructed from two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) building units[14]. For the simultaneous electro-adsorption removal of uranyl and rhenium (ReO4−), an asymmetric electrode system was constructed using carboxyl-functionalized COF (COF-1) as the cathode and cationic-functionalized COF (COF-2) as the anode. Under an applied voltage of 1.2 V, COF-1 exhibited a uranyl adsorption capacity of 411 mg/g, and COF-2 achieved a ReO4− adsorption capacity of 984 mg/g[28]. Yang et al. prepared carbonized wood-supported COF electrodes (CW@COFs) using a solvothermal method. The CW@COFs achieved the uranyl adsorption capacity of 2,510.7 mg/g under an applied potential of −2.4 V[29]. Noncovalent organic building blocks self-assemble to form SOFs that exhibit highly tunable structures and pores[21]. Research on the electrochemical extraction of uranyl using SOFs remains limited, as most existing studies have focused primarily on uranyl adsorption. For example, a phenanthroline-based supramolecular organic framework (MPSOF) demonstrated a remarkable electrochemical extraction capacity of 7,311 mg/g for uranyl ions at an applied potential of −3.5 V, which was attributed to the selective capture of uranyl ions by 1,10-phenanthroline-2,9-dicarboxylic acid (PDA) and the framework's efficient electron transfer capability[21]. Nitrogen- and oxygen-rich organic ligands have been utilized as building units to construct self-assembled SOFs for the adsorption of uranyl from radioactive wastewater. The MSONs synthesized from melamine (MA) and trimesic acid (TMA) exhibited a high U(VI) adsorption capacity of 526.6 mg/g, attributed to the strong coordination interactions between the carboxyl and amino groups within the framework and uranyl ions[30]. Furthermore, a flower-like superstructure assembled from carbamoyl acid (CA) and MA demonstrated a rapid and remarkable U(VI) adsorption capacity of 950.52 mg/g, arising from the synergistic interaction between phosphate and amino groups, which enhances uranyl affinity and uptake efficiency[31]. While POPs offer adjustable porosity and large surface area, and SOFs provide flexible, self-assembled frameworks with selective binding sites; both require improved electrical conductivity for practical electrode materials.

Powder-based electrode materials

-

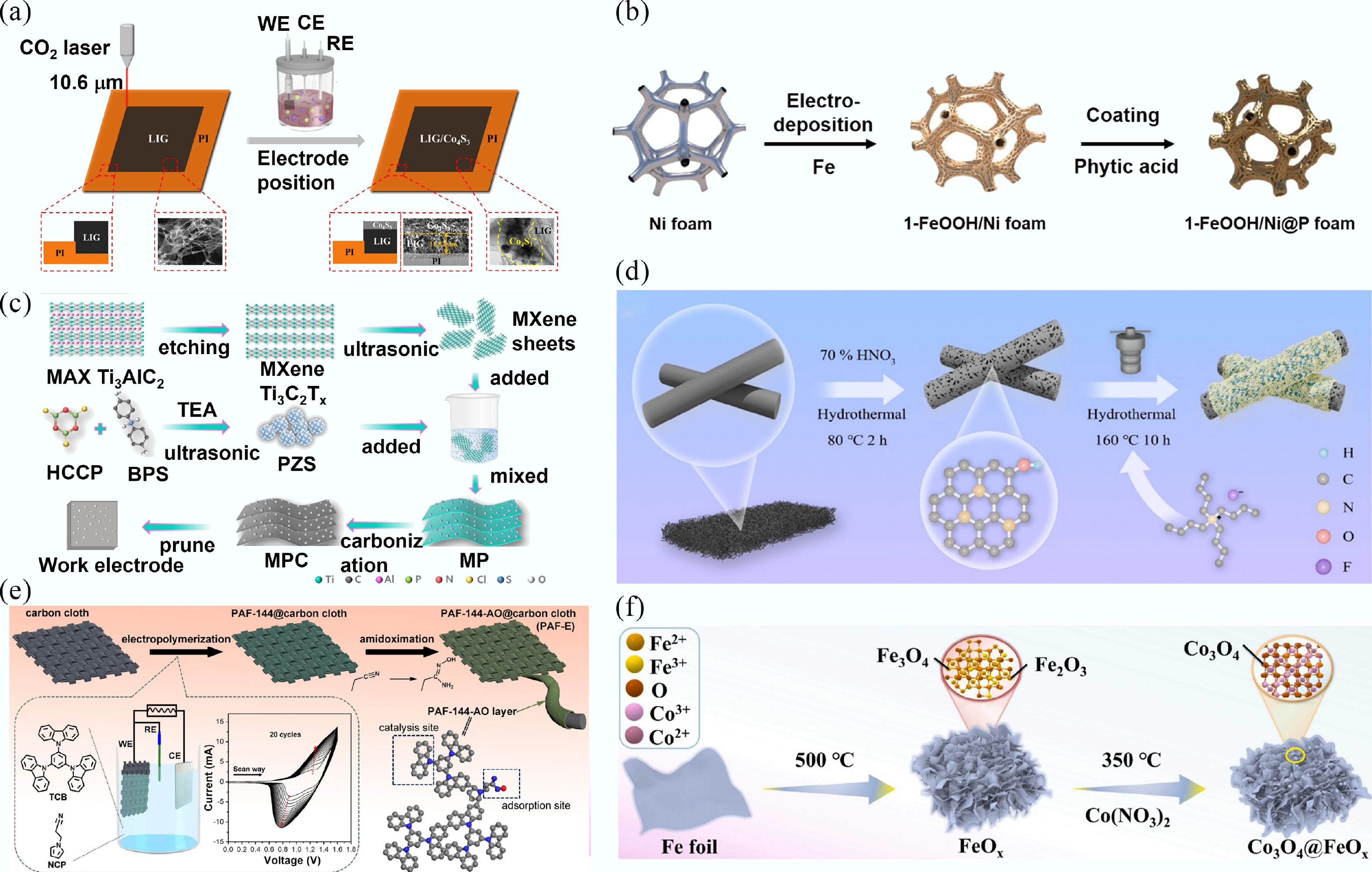

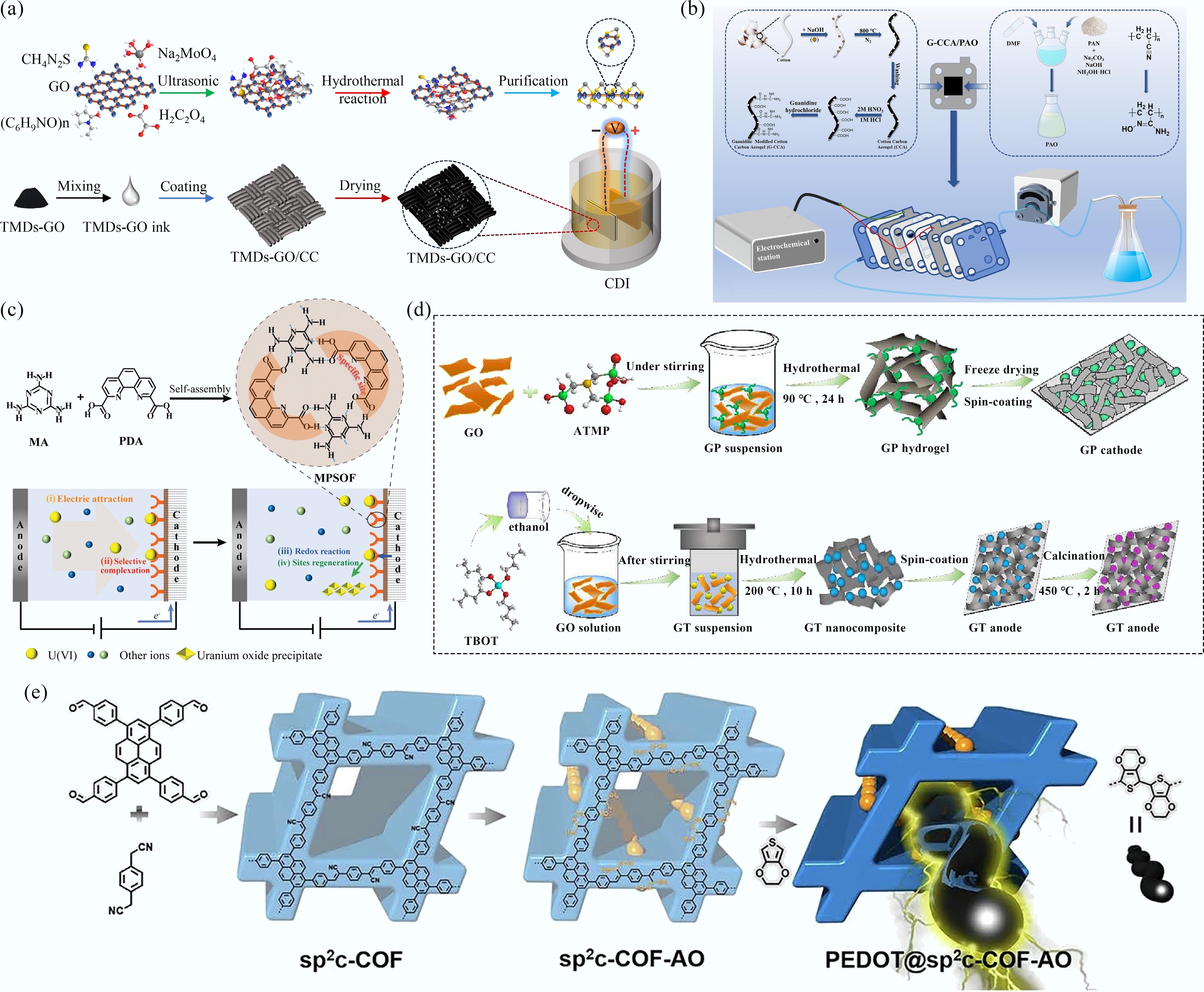

To date, most studies on electrochemical uranyl extraction have primarily employed powder-based electrocatalysts. These catalysts are typically synthesized via hydrothermal or self-assembly routes driven by non-covalent interactions[21], among other facile methods, and subsequently coated onto conductive substrates such as carbon cloth (CC)[32], titanium plate[33], Pt foil[34], graphite plates, and fluorine-doped SnO2 glass substrate (FTO)[35]. As shown in Fig. 2a, Wang et al.[32] synthesized a series of transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs)-GO composites (MoS2-GO, TiS2-GO, and WS2-GO) via a hydrothermal method for uranyl extraction from wastewater. The corresponding electrodes were prepared by coating a homogeneous slurry of TMDs-GO, carbon black (CB), and poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) binder (mass ratio 8:1:1, w/w) onto CC substrate, followed by drying at 80 °C for 3 h. A homogeneous catalyst slurry was obtained by mixing 1 mL of the polyamidoxime (PAO) solution with 30 mg of cotton-derived carbon aerogels (CCA) under vigorous stirring. The working electrode was prepared by coating the catalyst slurry onto a 2 cm × 2 cm titanium plate and then vacuum drying it for electrochemical extraction of uranyl ions (Fig. 2b)[36]. MPSOF powders were obtained through the hydrogen-bond-driven self-assembly of PDA and MA, enabling their application in the electrochemical extraction of uranyl ions (Fig. 2c). Specifically, 5 mg of conductive carbon black and 20 mg of MPSOF powders were dispersed in a 0.05 mL Nafion and 0.45 mL 1-methyl-2-pyrrolidone solution to form a uniform ink, which was subsequently coated onto CC, dried, and used to fabricate the SOF electrodes[21]. Similarly, phosphate-functionalized graphene (GP) powders were prepared via a hydrothermal reaction at 90 °C for 24 h. The GP electrodes were prepared by mixing GP powders, conductive carbon black, and PVDF binder in a mass ratio of 8:1:1 to form a homogeneous slurry, which was then spin-coated onto graphite plates and dried at 80 °C for 12 h. GO and tetrabutyl titanate solution were heated at 200 °C for 10 h, followed by centrifugation and washing to obtain the GO/TiO2 (GT) nanocomposites. The resulting GT powder was mixed with ethanol to form a paste, which was spin-coated onto cleaned FTO glass substrates and subsequently calcined at 450 °C in an argon atmosphere for 2 h to obtain the GT electrode (Fig. 2d)[35]. In another study, Song et al. synthesized sp2c-COF via the Knoevenagel condensation reaction, followed by treatment with NH2OH·HCl to yield sp2c-COF-AO. The subsequent incorporation of 3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene (PEDOT) molecules into the COF channels resulted in the formation of PEDOT@sp2c-COF-AO (Fig. 2e). The as-prepared powder was mixed with Nafion and ethanol to form a homogeneous paste, which was then coated onto the Pt foil and dried to obtain the electrode[34]. These examples collectively demonstrate that most reported powder-based electrodes rely on slurry-coating techniques to ensure intimate contact between the catalyst and the conductive substrate, thereby improving electron transfer efficiency and mechanical stability during electrochemical uranyl extraction.

Figure 2.

(a), (b) Schematic illustrations for the synthesis of TMDs-GO and fabrication of TMDs-GO/CC electrodes[32], and G-CCA/PAO electrode[36]. (c) Schematic illustration for the synthesis of SOF and electrochemical uranyl extraction[21]. (d), (e) Schematic illustrations of the synthesis of GP and GT materials[35], COF-based materials[34].

Self-supported electrode materials

-

Currently, most reported catalysts for electrochemical uranyl extraction are powder-based materials, which typically require incorporation into inks with conductive additives or polymer binders before being coated onto electrode substrates. However, the use of non-conductive polymer binders can hinder electron transfer between catalyst particles, thereby increasing electrode resistance and diminishing electrocatalytic efficiency. In addition, the binders may partially block the active sites on the catalyst surface, resulting in decreased electrode stability and reduced active site utilization[37]. To address these limitations, researchers have been actively developing self-supported electrode materials and advanced fabrication strategies aimed at enhancing the electrocatalytic efficiency and stability of electrochemical uranyl extraction systems.

Selection of self-supported substrates

-

Self-supporting electrodes are typically fabricated by directly growing electrocatalysts on conductive or non-conductive substrates. Common conductive substrates include FTO, indium tin oxide (ITO) glass, carbon-based materials such as CC and carbon felt (CF), as well as metal-based substrates including stainless steel, molybdenum foil, titanium foil, iron foils, copper foam, nickel foam, and iron foam[37]. In contrast, frequently used non-conductive substrates comprise textiles, paper, sponges, and other porous flexible materials[38].

Preparation method of self-supported electrocatalyst

-

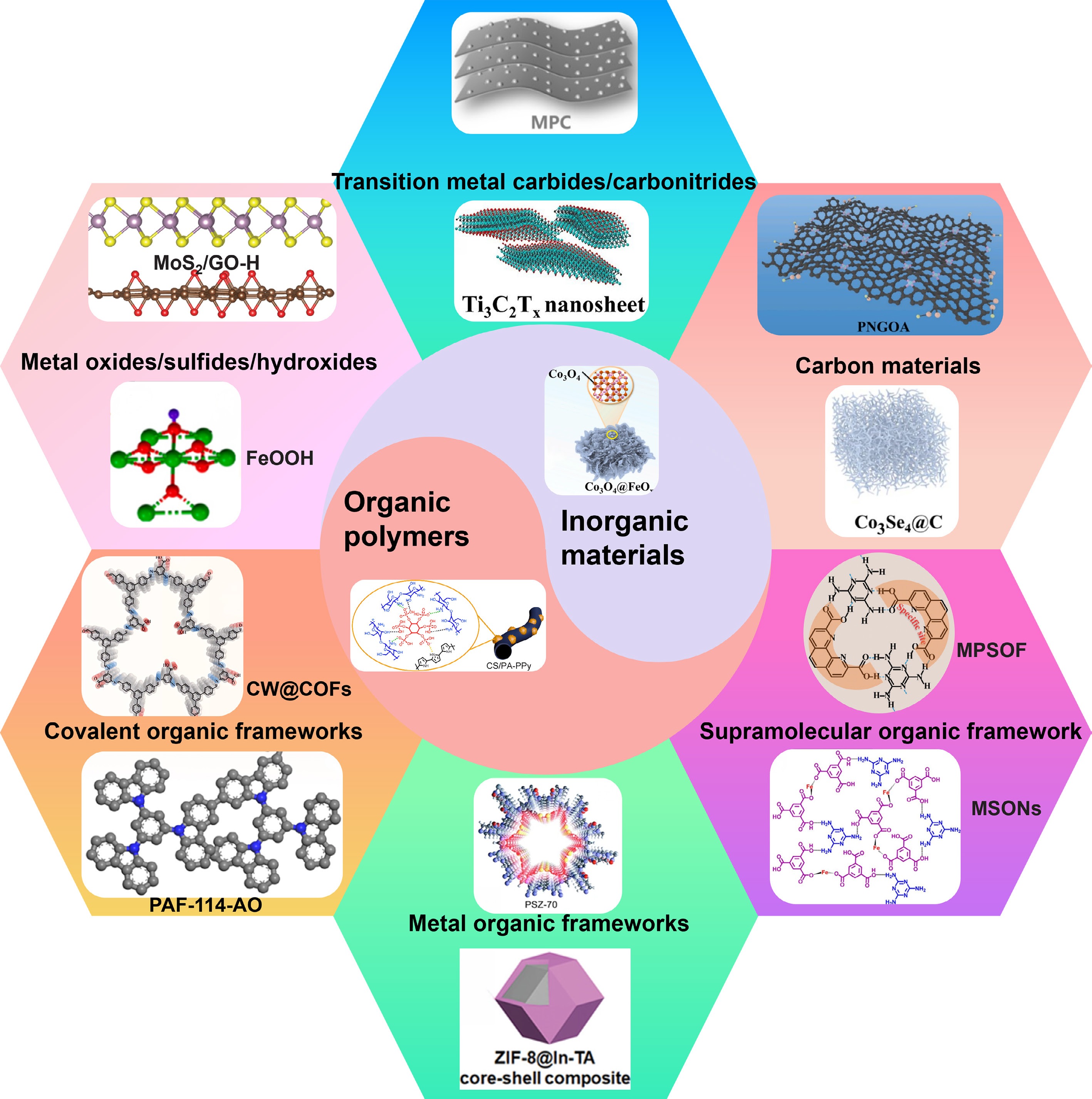

Self-supporting electrocatalysts are primarily fabricated through several established techniques, including laser-induced graphene (LIG)[39], electrochemical deposition[40], hydrothermal or solvothermal methods[41], electro-polymerization[20], electrochemical anodizing[42], and thermal treatment methods[43]. Electrodeposition is a widely utilized technique for fabricating electrocatalysts on conductive substrates due to its operational simplicity and short processing time[44]. For instance, Gao et al.[39] prepared LIG/Co4S3 electrodes using laser-induced graphene (LIG) and electrodeposition techniques. The LIG square electrodes were fabricated on polyimide films using CO2 laser system under varying laser powers. The electrodeposition of Co4S3 onto the LIG surface was conducted via cyclic voltammetry (CV) in a three-electrode electrochemical system, using LIG as the working electrode, a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) as the reference electrode, and a platinum sheet as the counter electrode, with 0.5 M CH4N2S and 5 mM Co (NO3)2 as the electrolyte (Fig. 3a). Li et al.[45] synthesized FeOOH/Ni@P foam on NF via a combination of electrodeposition and subsequent phytic acid coating (Fig. 3b). The electrostatic assembly method can be used to prepare membrane electrodes, as illustrated in Fig. 3c[46]. Ti3C2Tx powder and etching prepared polyphosphazene (PZS) was mixed in a 5:3 mass ratio, freeze-dried to obtain MXene/PZS (MP), and then calcined under nitrogen to yield a self-supporting electrode (MPC) membrane electrode. Meanwhile, the modified CF (MCF) electrode was fabricated via a two-step hydrothermal method. The CF was pretreated in HNO3 at 80 °C for 2 h, followed by hydrothermal reaction in tetrabutylammonium fluoride at 160 °C for 10 h to obtain the MCF electrode (Fig. 3d)[41]. The porous aromatic framework (PAF)-114 electrodes were synthesized via electro-polymerization using N-(2-cyanoethyl)pyrrole (NCP) and 1,3,5-tri(N-carbazoyl)benzene (TCB) as monomers, with CC serving as the substrate (Fig. 3e)[20]. Wang et al.[42] prepared TiO2 electrode using the anodic oxidation method. Their experimental setup involved an electrophoresis apparatus with a Ti sheet configured as the anode and a Pt sheet as the cathode, operated at an applied voltage of 40 V in an electrolyte solution of NH4F and (CH2OH)2. Moreover, the self-supporting Co3O4@FeOx nanosheet arrays were fabricated using two-step heat treatment methods. Pre-treated iron foil was calcined at 500 °C for 4 h in air to form FeOx foil, followed by immersion in a 0.1 M Co(NO3)2·6H2O solution for 12 h, and subsequent annealing at 350 °C for 30 min to yield the final electrode[43] (Fig. 3f).

-

Capacitive deionization (CDI)[47], also known as electro-absorption, employs an externally applied electric field to drive the adsorption of ions onto electrode surfaces, offering a sustainable and energy-efficient method for the remediation of radionuclide-contaminated water. In a typical CDI cell[48], an applied voltage establishes an electric field between the working and reference electrodes, which drives the migration of ions or charged species from the bulk solution toward the electrode/electrolyte interface, where electrical double layers (EDLs) are formed[6]. The separation of cation and anion from the solution is governed by either EDL formation occurring at the corresponding electrodes[49]. Electro-adsorption is a non-Faradaic process in which ions are electrostatically accumulated within the EDLs without undergoing valence changes, whereas electrocatalysis is a Faradaic process involving electron-transfer reactions, including anodic oxidation, cathodic reduction, and Faradaic ion storage[16]. Although both occur at the electrode interface and are controlled by applied potential, electro-adsorption focuses on ion enrichment, while electrocatalysis drives redox conversion.

Electrode materials for extraction of uranyl by electro-adsorption

-

The application of CDI for uranyl removal from aqueous solutions is still in its early stage of development, with the properties of electrode materials exerting a critical influence on overall extraction performance[24]. To date, the primary electrodes utilized in CDI systems for uranyl removal are carbon-based materials, including graphene aerogels[47,50], GO[18], template porous carbons[51], CNTs[6,52], and activated carbons[33], etc. The limited selectivity of pristine carbon-based materials towards uranyl ions has prompted the extensive development of carbon-based composites as electrode materials for electro-adsorption extraction of uranyl ions. For instance, Shuang et al.[53] developed a GO/polypyrrole (GO/PPy) electrode with a capacity of 246.5 mg/g at 0.9 V owing to its open interlayer channels and high specific capacitance. Biomass-derived porous activated carbons with large pore volume and high specific surface area have been obtained from natural sources such as coconut shells, rice straw, cotton, and wood[33]. Yu et al.[54] synthesized biomass-derived carbon/polypyrrole electrodes showing a uranyl electro-adsorption capacity of 237.9 mg/g at 0.9 V. Porous carbon materials derived from MOFs as sacrificial templates offer high surface areas and abundant pore structure. Zhang et al.[51] synthesized a Zr-NC/MXene composite from Zr-MOF with a uranyl adsorption capacity of 582.46 mg/g.

The incorporation of materials such as transition metal oxides and metal sulfides onto carbon supports can produce synergistic effects, enhancing the overall adsorption, mass transfer, and electrochemical properties. As an example, the porous GO/α-MnO2/polyaniline electrodes exhibited a specific capacitance of 303.85 F/g and a uranyl electro-adsorption capacity of 330.41 mg/g, highlighting a strong correlation between electro-adsorption capacity and specific capacitance[55]. While rational design of electrode materials can improve uranyl adsorption, the performance of electro-adsorption is limited by co-ion expulsion effects[56]. Specifically, the presence of interfering cations such as Na+, Ca2+, and Fe3+ limits the selectivity of electro-adsorption toward uranyl ions, as non-specific adsorption on the electrode surface decreases both the overall removal efficiency and adsorption capacity of uranyl[57].

Electro-adsorption mechanisms of uranyl

-

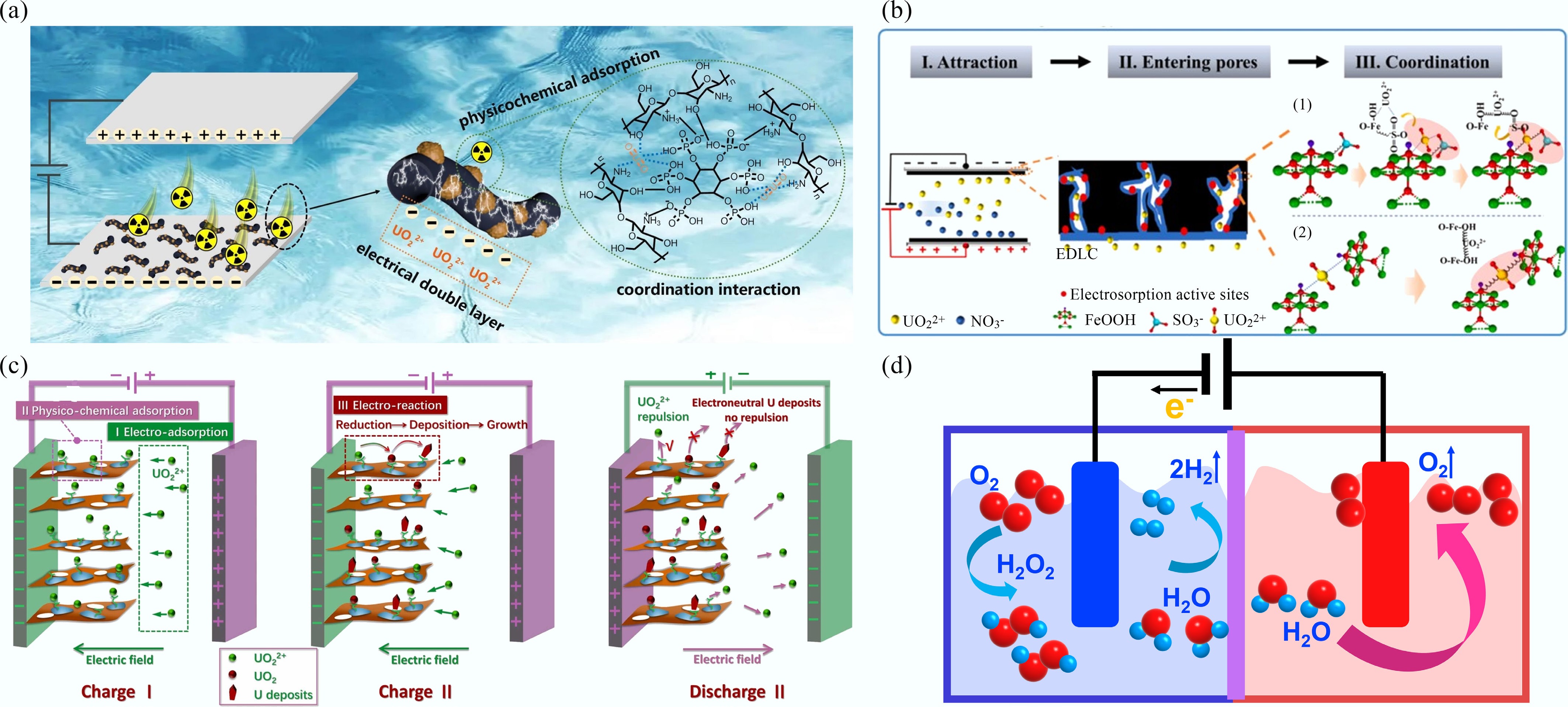

As shown in Fig. 4a, uranyl ions were initially adsorbed onto the cathode via physicochemical adsorption and then accumulated within the EDLs on the electrode surface. This synergistic interplay between physicochemical and capacitive adsorption facilitated the formation of solid products[58]. The electro-adsorption mechanism of uranyl ions on FeOOH nanorods, as reported by Jiao et al., is illustrated in Fig. 4b. Uranyl ions were initially attracted to the FeOOH electrode surface via electrostatic interactions and subsequently entered the hierarchical pores, where surface-bound acid groups (–SO3H) and Fe-OH moieties coordinated with the uranyl ions, leading to their effective immobilization[59]. The electro-sorption mechanism of uranyl ions by niobium phosphate/holey graphene electrode is illustrated in Fig. 4c. Positively charged uranyl ions are attracted to the electrode surface, coordinated with -P-O and -Nb-O sites, and reduced to U(IV), which deposits on the electrode surface. Consequently, released active sites and intercalation pseudo capacitance enable continuous re-adsorption and reduction of U(VI), ensuring high capacity, fast kinetics, and excellent selectivity[60].

In addition to elucidating the electro-adsorption mechanism of uranyl, some potential Faradaic side reactions must also be considered[61]. During electrochemical uranyl extraction, side reactions involving water reduction can produce hydrogen and oxygen, which increases energy consumption, reduces uranyl selectivity, and may damage equipment. However, H2O2, another side product of water reduction can play a beneficial role by precipitating uranyl, thus enhancing the overall extraction efficiency and capacity (Fig. 4d).

Electrocatalysis

Basic principles of electrocatalysis

-

As an emerging technique, electrochemical uranyl extraction demonstrates high capacity and rapid kinetics by uranyl ions reduction under the guidance of an applied electric field, employing methods such as half-wave rectified alternating current electrochemistry (HW-ACE), potentiostatic polarization (i-t curve), and CV[62]. Electrocatalysis at the electrode-electrolyte interface is a complex process typically involving reactant adsorption, charge carrier diffusion, surface reactions, and product deposition[63].

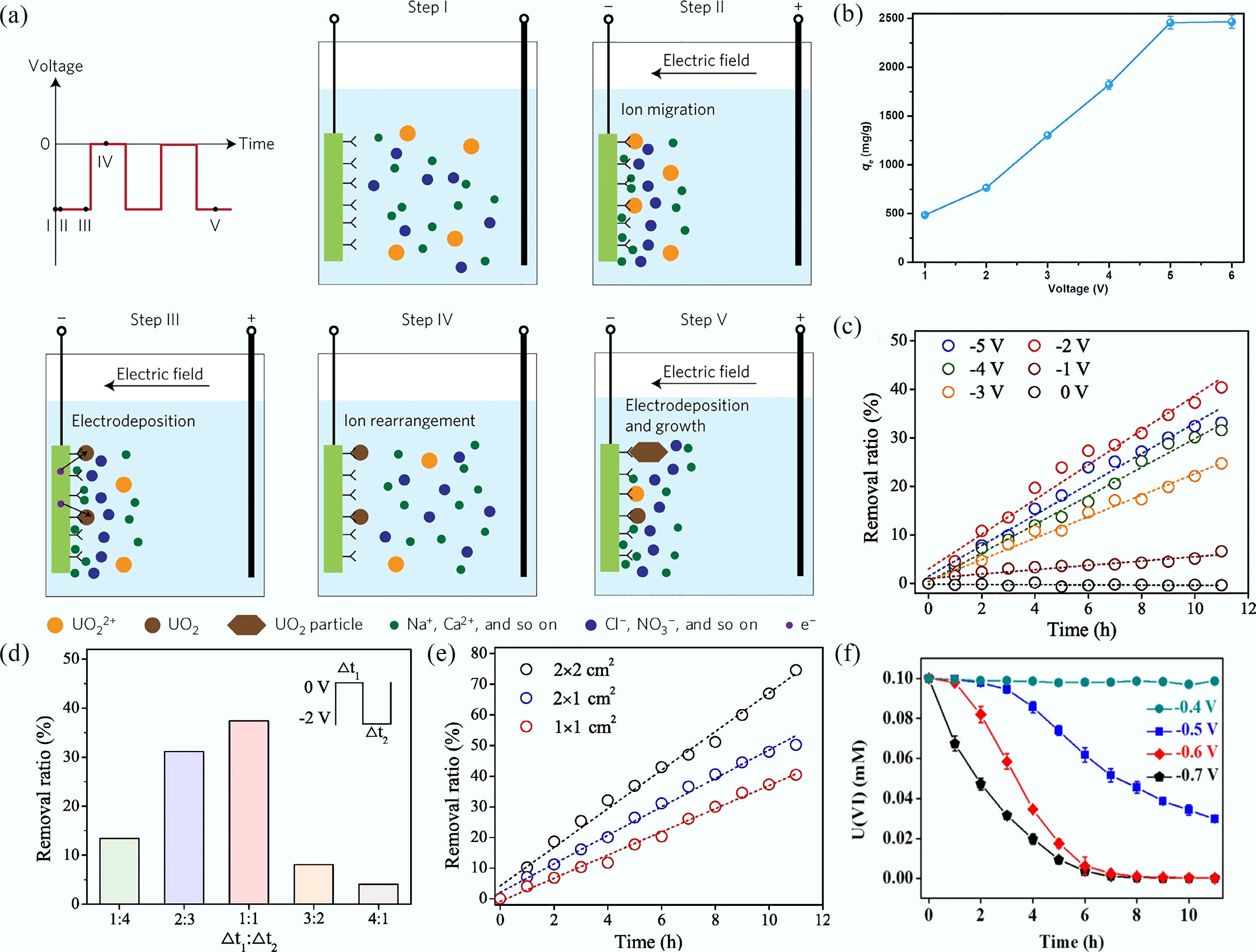

In 2017, Cui's group[64] pioneered the extraction of uranyl from seawater using the HW-ACE method, achieving a maximum extraction capacity of 1,583 mg/g. The HW-ACE process for uranyl ion extraction proceeds as follows: (I) Ions are dispersed in solution; (II) Under the applied electric field, ions migrate and adsorb onto the electrode surface; (III) Uranyl ions are reduced to uranium dioxide (UO2); (IV) Removal of the bias voltage releases coexisting ions back into the solution; (V) Continued adsorption and electrodeposition of uranyl ions promote the growth of UO2 particles (Fig. 5a). HW-ACE uranyl extraction is typically performed in a two-electrode system, featuring a customized cathode and a carbon-based anode, with the applied voltage alternating between −5 and 0 V at 400 Hz[64]. As illustrated in Fig. 5b, voltage significantly influences the uranyl extraction capacity. Specifically, the extraction capacity of uranyl continuously increased as the voltage was raised from −1 to −6 V. To reduce energy efficiency, the uranyl extraction was ultimately conducted at a voltage of −5 V. However, when utilizing boron-doped diamond (BDD) electrodes for uranyl extraction, U(VI) removal efficiency does not increase monotonically with voltage. The optimal voltage occurs at −2 V, likely due to the inherent material properties of BDD electrodes (Fig. 5c). The extraction efficiency of uranyl is influenced by multiple factors, including the frequency of the UTG1005A instrument, power-off/power-on on time ratios (Fig. 5d), electrode surface area (Fig. 5e)[65], electrolyte composition and concentration, solution pH value, and the presence of interfering co-ions, etc.

Figure 5.

(a) The uranyl extraction processes in HW-ACE[64]. (b) Effect of the voltage at uranyl-spiked seawater. (c) Electrochemical removal of uranyl at different voltages using HW-ACE method. (d) Electrochemical removal of uranyl at different time ratios of power-off/power-on at the certain frequency (400 Hz). (e), (f) Electrochemical removal of uranyl at different contact areas[65] and different potentials[67].

The CV and i-t measurements were typically performed in a standard three-electrode system, consisting of the prepared electrode as the working electrode, a platinum mesh as the counter electrode, and Ag/AgCl as the reference electrode. In this system, the applied voltage represents the potential difference between the reference electrode and working electrode, which plays a crucial role in the electrocatalytic reduction of uranyl ions[66]. Liu et al.[67] demonstrated that the uranyl removal efficiency increased markedly as the applied potential rose from −0.4 to −0.7 V (Fig. 5f). The choice of electrolyte strongly affects the extraction efficiency of uranyl ions. For instance, sodium chloride and sodium nitrate have been found to enhance uranyl extraction efficiency, while sodium sulfate tends to suppress it due to competitive adsorption of excess Na+ ions with U(VI) at the electrode interface[68]. These observations highlight the importance of carefully selecting both electrolyte composition and applied potential to optimize uranyl recovery. Previous research on electrocatalytic uranyl extraction has consistently employed specific voltage or current parameters, despite differences in instrumentation. Regardless of whether a two- or three-electrode configuration was used, the extraction efficiency of uranyl ions was found to depend on factors such as applied voltage, electrolyte solution, coexisting ions, and solution pH.

Electrode materials for uranyl reduction by electrocatalysis

-

The principal electrode materials employed for electrocatalytic uranyl extraction include transition-metal-based materials, as well as amidoxime-functionalized carbon materials or other composites. For uranyl extraction, Wang et al.[69] developed a bipolar electrochemical system consisting of a nanoscale zero-valent copper (NZVC)-decorated carbon cloth anode, a titanium sheet cathode, and an electrolyte. When operated at an applied voltage of 0.6 V, the system achieved a uranyl extraction efficiency of 100% and maintained long-term stability over 45 cycles. Similarly, Lin et al.[70] synthesized rutile and anatase electrodes on Ti mesh to further explore phase-dependent electrocatalytic behavior. The anatase-based electrode exhibited nearly twice the adsorption and electron transfer rates of the rutile counterpart, which was attributed to its highly ordered 1D nanotube architecture, facilitating efficient charge transport and separation.

Researchers have extensively investigated amidoxime-based materials owing to their strong chelating affinity toward uranyl ions and their potential for selective recovery from complex aqueous matrices such as wastewater and seawater. For instance, an amidoxime-functionalized polyarylether-based COF electrode effectively coordinated uranyl ions through amidoxime ligands, while the in situ generated H2O2 further promoted uranyl precipitation, resulting in an extraction capacity of 9,238.9 mg/g from organic wastewater[71]. Similarly, an amidoxime-functionalized indium-nitrogen-carbon electrode exhibited a capacity of 6.35 mg/g/d for uranyl extraction from natural seawater[72]. These results collectively highlight that rational molecular design and heteroatom coordination engineering within amidoxime-based frameworks can significantly enhance both the selectivity and kinetics of electrochemical uranyl extraction.

Electrocatalysis mechanisms of uranyl

-

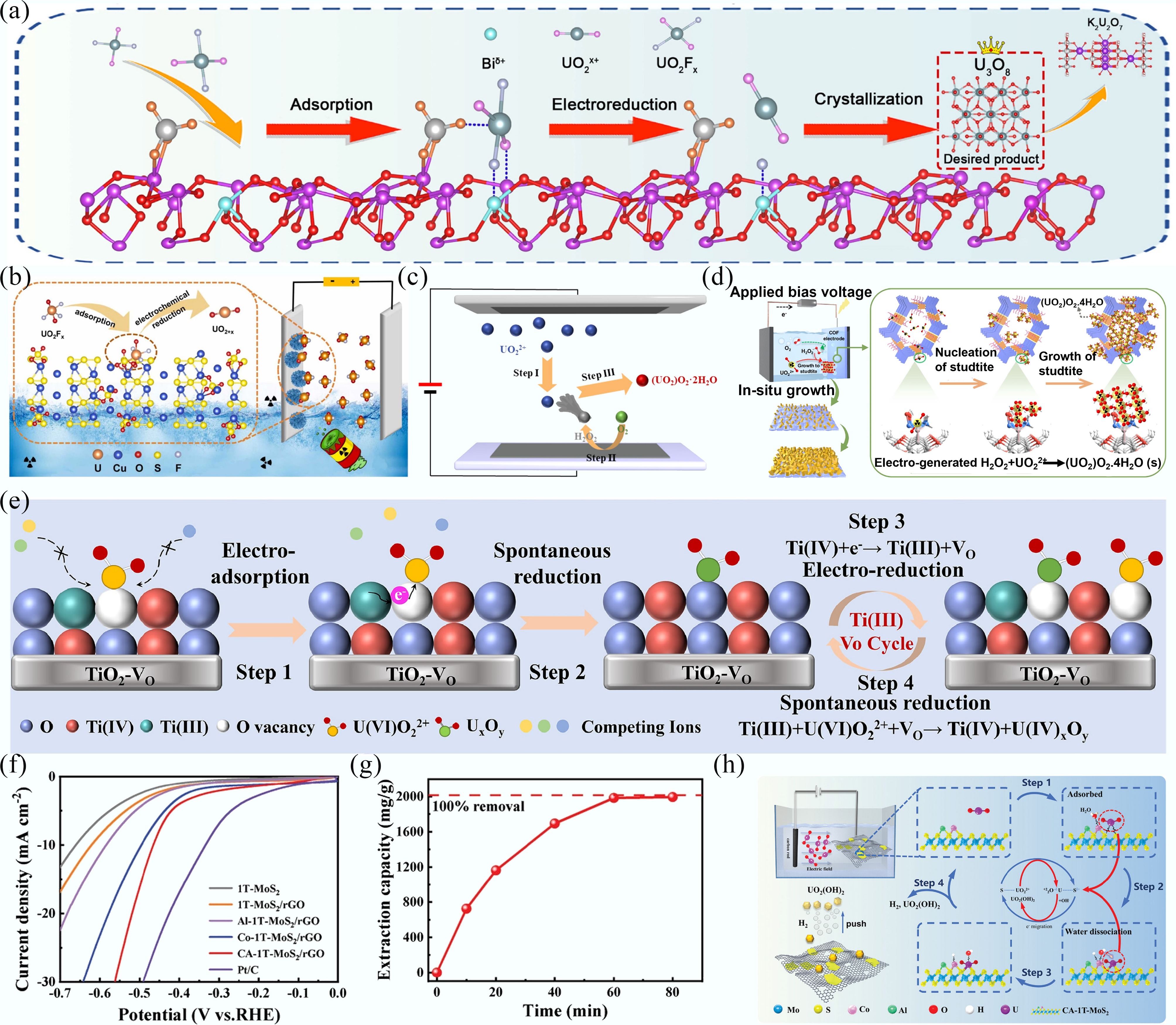

The electrocatalytic extraction of uranyl generally proceeds through an initial adsorption of uranyl ions onto the electrode surface, followed by their reduction into insoluble solid products. In the Ca5(PO4)3(OH)-Bi2O3-x system, surface Lewis sites facilitate the adsorption of uranyl ions and uranyl fluoride complexes. Under an applied electric field, the uranyl fluoride complexes are forced to separate, resulting in the formation of U(V), which subsequently crystallizes and grows into U3O8 and K2U2O7[73] (Fig. 6a). A similar mechanism was observed for the Cu+-SOx electrode, where uranyl fluoride complexes were first anchored onto the open Cu+-SOx active sites and then electrochemically reduced to uranium oxides under the applied potential(Fig. 6b)[74].

Figure 6.

(a), (b) The mechanism for electrocatalytic reduction of uranyl by Ca5(PO4)3(OH)-Bi2O3-x[73] and Cu-S-O nanosheets[74]. (c), (d) Schematic diagram for uranyl extraction using Co3Se4@C[75] and PAE-COF-AO@CC[71]. (e) The removal mechanism of electrochemical method for TiO2-VO electrode[42]. (f) LSV curves of different materials. (g) Uranyl extraction capacity plot in 100 mg/L uranyl-containing simulated seawater. (h) Schematic diagram for uranyl extraction using the electrochemical method[76].

The electrocatalytic oxygen reduction approach for uranyl extraction operates through a distinct mechanism compared with conventional electrochemical reduction. Initially, uranyl ions are adsorbed on the electrode surface (Step I), followed by oxygen reduction to generate H2O2 (Step II). The resulting H2O2 reacts with uranyl ions to form solid UO2(O2•2H2O (Step III)) Fig. 6c[75]. In the case of amidoxime-functionalized COF electrodes, amidoxime ligands selectively capture uranyl ions, while the in situ generated H2O2 initiates and accelerates the formation of solid studtites (Fig. 6d)[71].

In the electrocatalytic reduction of uranyl, most studies employ high voltages. In contrast, Wang's group pioneered the use of low voltages (−0.01 V) for uranyl extraction. Under the action of an electric field, uranyl ions first adsorb onto oxygen vacancies on the TiO2-VO electrode surface, which promotes the reduction of U(VI) to U(IV) via Ti(III) species. The oxidized Ti(IV) is then regenerated to Ti(III) through electron transfer, establishing a continuous spontaneous redox cycle (Fig. 6e)[42].

Some studies have reported a correlation between high hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) performance and enhanced uranyl extraction efficiency[76], indicating a mechanism distinct from conventional electrocatalytic pathways. For example, Co- and Al- modified 1T-MoS2/reduced graphene oxide (CA-1T-MoS2/rGO) exhibited remarkable HER performance, achieving an overpotential of 466 mV at 10 mA/cm2 in simulated seawater (Fig. 6f). Benefiting from this high HER performance, the electrode achieved a uranyl removal efficiency of 99% within 1 h in simulated seawater (Fig. 6g). The extraction mechanism on the CA-1T-MoS2/rGO electrode (Fig. 6h) begins with the adsorption and dissociation of H2O molecules on Co atoms, generating plentiful H* and OH*. Uranyl ions then migrate to the cathode, adsorb onto S atoms, and undergo electron transfer, facilitating their reaction with OH* to form UO2(OH)2 precipitate. Importantly, the HER-generated bubbles assist in detaching the precipitate from the electrode surface, thereby ensuring the electrode's reusability[76].

Photo-electrocatalysis

Basic principles of photo-electrocatalysis

-

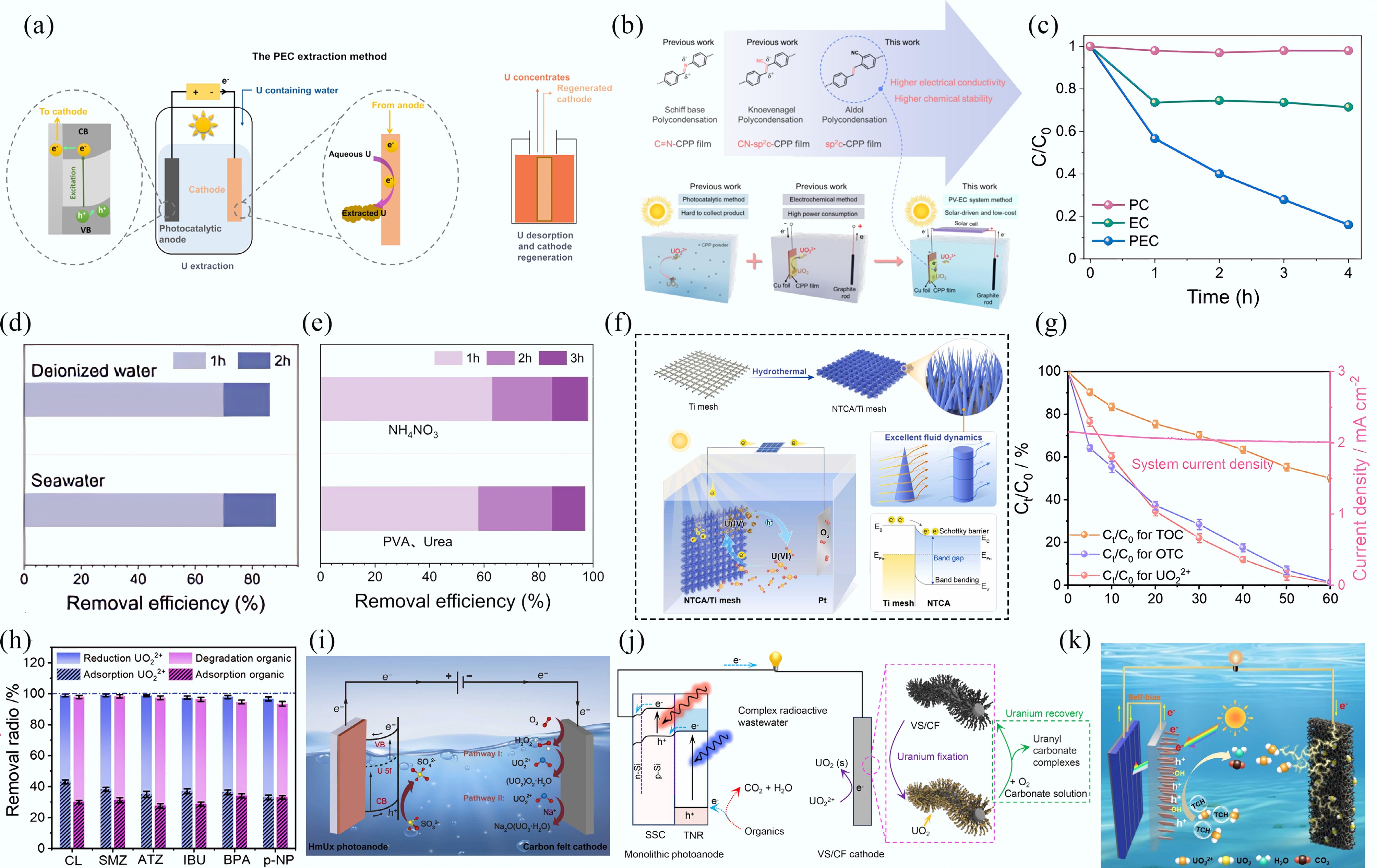

While photocatalysis and electrocatalysis have emerged as promising methods for uranyl extraction, the former is limited by rapid charge carrier recombination, whereas the latter often suffers from high energy consumption. Photo-electrocatalysis (PEC) addresses these limitations by utilizing the migration of photogenerated electrons/holes, facilitated through the application of an electrical potential across a semiconductor-based photocatalyst assembled on an electrode connected to a direct current supply[77]. A typical PEC cell comprises two electrically connected electrodes immersed in an electrolyte, with a semiconductor photoelectrode for light harvesting (Fig. 7a). The applied bias voltage drives effective charge carrier separation, enabling the conversion of solar energy into electrical energy and thereby reducing overall energy expenditure[78].

Figure 7.

(a) The PEC uranyl extraction method[78]. (b) Engineering of the sp2c-CPPs electrodes for solar-driven electrochemical uranyl extraction[79]. (c) PEC, EC, and PC performance of the NTCA/Ti mesh. (d) PEC performance evaluation with real seawater. (e) PEC performance evaluation with real uranium-containing wastewater. (f) The PEC investigation of uranyl immobilization on the NTCA/Ti mesh[81]. (g) Performance of PEC for simultaneous uranyl removal and OTC degradation. (h) Removal efficiencies of uranyl and organics in the treatment of different organic pollutants[86]. (i)−(k) Schematic illustration of the HmU-based photoelectrochemical system[87], VS/CF cathode and TNR anode[88], and NF cathode and TNR photoanode[89] for uranyl extraction.

To enhance the utilization of solar energy, photovoltaic-electrocatalysis (PV-EC) technology has been developed. PV-EC systems employ photovoltaic cells to convert solar energy into electrical energy, which subsequently drives the reduction of uranyl ions. The sp2-carbon-conjugated porous polymer (sp2c-CPP) film electrode was prepared through in-situ aldol polycondensation on a Cu substrate. In the PV-EC system, the electrochemical component comprises a graphite rod anode, sp2c-CPP film cathode, and a electrolyte. This solar-driven PV-EC configuration is both environmentally friendly and cost-effective, alleviating the high energy consumption associated with conventional electrochemical systems and addressing the product collection challenges encountered in photocatalytic approaches (Fig. 7b)[79].

Electrode materials for uranyl extraction by photo-electrocatalysis

-

Currently, some semiconductor-based photo-electrocatalytic systems, including SrTiO3, CuO/CuFeO2, g-C3N4, CoOx, BiVO4-modified WO3, and TiO2, have been developed for aqueous U(VI) extraction. These semiconductor electrodes serve a unique role by harvesting light to provide the energy required for the reactions and facilitating the associated chemical oxidation-reduction processes[80]. Li and colleagues fabricated nano-TiO2 arrays on Ti mesh (NTCA/Ti) for the uranyl extraction. As illustrated in Fig. 7c, the removal rate of uranyl achieved via PEC is significantly higher than that obtained using either electrocatalysis (EC) or photocatalysis (PC) alone. The NTCA/Ti electrode shows outstanding uranyl extraction performance in deionized water, spiked seawater (Fig. 7d), and two real wastewater types: one containing polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and urea, and the other containing ammonium nitrate (Fig. 7e). The illumination of NTCA/Ti mesh generates of electron-hole pairs, with photogenerated holes transported to the Pt electrode through an external circuit, while the electrons reduce U(VI) to U(IV). This synergistic integration of photocatalytic and electrocatalytic functionalities enables efficient uranyl immobilization and reduction without the need for sacrificial agents (Fig. 7f)[81].

Kim et al.[82] found that the PEC method achieved superior uranyl extraction efficiency using TiO2 compared to both photo-catalytic and electro-catalytic treatments. Hu et al.[83] similarly found that SrTiO3/TiO2 nanofibers exhibited a uranyl removal capacity of 81 mg/L, markedly surpassing the 59 mg/L achieved by TiO2 and the 40 mg/L removed by SrTiO3 individually. The CuO/CuFeO2 electrode achieved the complete removal of 30 mg/L of uranyl under a voltage of −0.6 V and simulated sunlight, significantly outperforming the performance of either CuFeO2 or CuO individually[84]. A g-C3N4/Sn3O4/Ni electrode was constructed for photo-electrocatalytic uranyl reduction. At pH 5.0, this electrode achieved a uranyl removal efficiency of 94.28%, markedly surpassing the removal rates of 36.65% and 10.56% observed for purely electrochemical and photocatalytic conditions, respectively[85].

In some PEC systems, the photoanode generates hydroxyl radicals (•OH) and holes (h+) to oxidize organic pollutants, while photogenerated electrons migrate to the cathode to selectively reduce uranyl ions. Zhang et al. demonstrated this approach using an oxygen vacancy-enriched cobalt oxide modified carbon felt (OvCoOx/CF) cathode and a BiVO4-modified WO3 nanoplatelet array photoanode, achieving complete uranyl and oxytetracycline hydrochloride (OTC) within 60 min, with a total organic carbon (TOC) removal efficiency of 54.7% (Fig. 7g). To investigate the applicability of this PEC system to other organic wastewater systems containing uranyl, the extraction efficiencies were examined for common organic pollutants, including p-nitrophenol (p-NP), ibuprofen (IBU), sulfamethoxazole (SMZ), bisphenol A (BPA), atrazine (ATZ), and ciprofloxacin (CIP). The high removal efficiency of over 93.5% for both uranyl and these organics suggests that the PEC system generates •OH and h+, which are responsible for degrading organic matter (Fig. 7h)[86].

Photo-electrocatalysis mechanisms of uranyl

-

The mechanism of photo-electrocatalytic uranyl extraction primarily relies on photoinduced electrons that drive the reduction of uranyl ions. In this PEC process, photoexcited electrons reduce dissolved oxygen through a two-electron pathway to generate H2O2, which subsequently reacts with uranyl ions to form (UO2)O2·2H2O. In the presence of Na+ ions, soluble U(VI) is further oxidized and transformed into solid Na2O(UO3·H2O) (Fig. 7i)[87]. The low-valent V3+ and V4+ species on the VS/CF electrode act as electron donors, facilitating the reduction of U(VI) to UO2 and the formation of V5+. Continuous electron supply from the photoanode ensures the reduction of V5+ back to V3+/V4+, thereby regenerating the active sites and enabling sustained uranyl ion extraction(Fig. 7j)[88]. Fu et al.[89] developed a self-driven PFC system using 3D cross-linked nickel foam (NF) as the cathode and a TiO2 nanorod array (TNR) as the photoanode, achieving a uranyl recovery ratio of 99.4% and a tetracycline hydrochloride (TCH) removal ratio of 97.7% under simulated sunlight within 2 h. A possible extraction mechanism for the self-driven PFC system is proposed, as shown in Fig. 7k. The self-driven PFC system extracts uranyl ions through a photo-electrocatalytic process. The TNR photoanode, under sunlight (< 412 nm), generates electron-hole pairs (e−/h+). Meanwhile, the Si photovoltaic cell (Si PVC) converts transmitted light into electrical energy, creating a self-bias potential. This potential drives photoexcited electrons from the TNR to the NF cathode. At the cathode, these electrons reduce U(VI) to insoluble U(IV). Simultaneously, h+ and derived •OH on the TNR oxidize TCH to CO2 and H2O.

-

Uranium is the most common nuclear fuel employed in nuclear power plants worldwide[90]. The nuclear fuel cycle consists of several stages: first, uranium is recovered from uranium ore. Next, uranium is converted into uranium hexafluoride (UF6). Then, the enrichment of 235U occurs in UF6. Finally, UF6 is converted into uranium dioxide (UO2) for fuel fabrication[91]. However, this cycle inevitably generates large volumes of fluoride-rich nuclear wastewater, which poses potential threats to human health and significant environmental risks. The extraction of uranyl from fluoride-rich wastewater is complicated by the formation of stable uranyl fluoride complexes, including the anionic species[92] UO2F+, UO2F2 (aq), UO2F3−, and UO2F42−. The presence of fluoride ions (F−) competitively binds with uranyl, diminishing the ability of extraction materials to effectively capture and remove uranyl, thus lowering extraction efficiency and adsorption capacity[90]. Consequently, the efficient removal and separation of uranyl from fluoride-rich nuclear wastewater are crucial for maintaining the sustainability of the nuclear fuel cycle and protecting the environment.

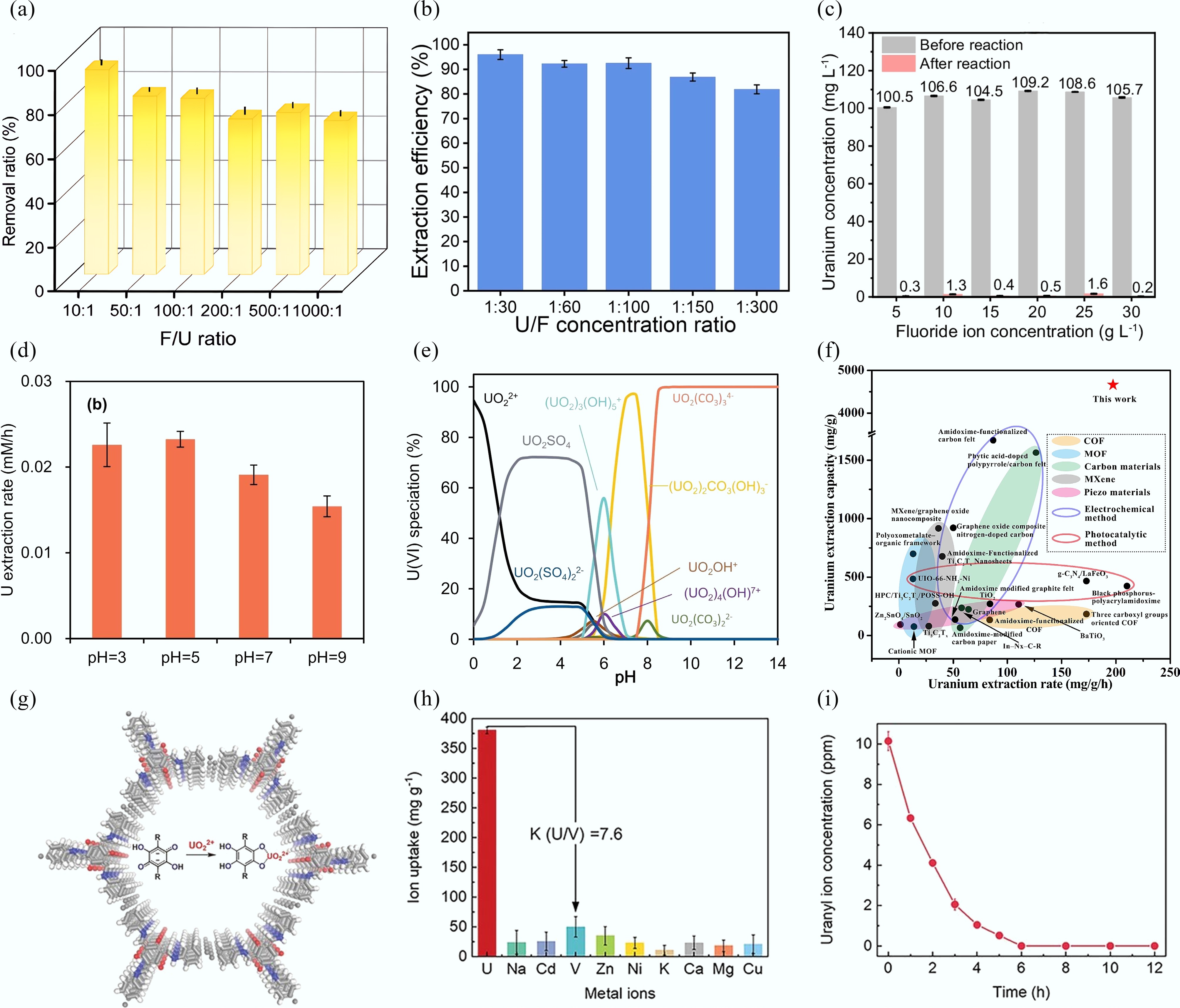

The research article on electrochemical methods for extracting uranyl from fluoride-rich nuclear wastewater is limited. The OH-rich CoOx nanosheets exhibited a 95% uranyl extraction ratio within 6 h in the presence of 100 mg/L F−. However, higher fluorine/uranium ratios result in a gradual decrease in uranyl removal efficiency (Fig. 8a)[93]. Wang et al.[74] designed the flower-structured Cu-S-O nanosheet electrodes using pulse electro-oxidation in simulated wastewater with a F− concentration of 3 g/L, which achieved the uranyl removal ratio of 98.6% in 300 min. The high concentration of F− also hampered the uranyl removal efficiency (Fig. 8b). In the presence of 10 g/L F−, the removal ratio of self-supporting Co3O4@FeOx nanosheet arrays for uranyl was 99.61%, thanks to the formed p-n heterojunction, accelerating the electroreduction kinetics of uranyl[43]. The Ca5(PO4)3(OH)-Bi2O3-x electrode was able to remove uranyl from real wastewater in the presence of 30 g/L F− with the U(VI) extraction efficiency of 99.9%[73]. The Ti(OH)PO4 electrode was reported to achieve high extraction efficiency of 99.6% and extraction capacity of 6,829 mg/g within 7 h in real wastewater. As the F− concentration increased from 5 to 30 g/L, nearly all of the 100 mg/L uranyl was removed, a phenomenon attributed to the formation of Tiδ+-PO43− ion pairs on Ti(OH)PO4 (Fig. 8c)[94].

Figure 8.

(a), (b) Uranyl extraction efficiency at various fluorine/uranium ratios by CoOx[93] and Cu-S-O nanosheets[74]. (c), (d) Uranyl extraction efficiency with different F− concentration[94], and varying pH value. (e) The modelled pH-dependent uranyl speciation profile[99]. (f) Comparison of uranyl extraction performance in electrochemical methods, and other reported methods or materials[100]. (g) Structural diagram of MICOF-14. (h) Ion uptake of MICOF-14 for uranyl ions in the presence of various interfering ions. (i) Removal capability of MICOF-14 from 10 mg/L uranyl aqueous solution[105].

Electrochemical extraction of uranyl from mine wastewater

-

The expansion of nuclear energy and the increasing number of nuclear power plants have led to a growing demand for uranium resources. Currently, terrestrial uranium resources are primarily obtained through uranium mining[95]. The uranium mining process utilizes significant amounts of acid for uranyl extraction, thereby generating acidic uranium-containing wastewater[96]. The concentrations of uranyl in the mine wastewater varied from tens of micrograms per liter (µg/L) to tens of milligrams per liter (mg/L)[7]. Alkaline uranium ore wastewater is also prevalent. Its primary species include about 30% UO2(CO3)22− and about 60% UO2(CO3)34−, posing a risk of infiltration into groundwater systems[9]. If uranium mine wastewater is not properly treated before being released into the natural environment, it poses a serious threat to human health and the ecological environment[10]. Therefore, it is essential to extract and removal uranyl from uranium mine wastewater for environmental protection.

To enhance the selectivity for uranyl, several functional groups, including amidoxime[96], carboxyl[97], phytic acid (PA)[98], and polydopamine (PDA)[2], have been introduced on materials. At an applied potential of −2.5 V, the amidoxime-modified carbon cloth exhibited a high electro-sorption capacity of 989.5 mg/g for uranyl removal[96]. The amino-functionalized MIL-101 was modified with the 1,2,3,4-butane tetracarboxylic acid ligand to extract uranyl from wastewater. At an applied voltage of −0.9 V, the maximum adsorption capacity of MIL-101-COOH for uranyl reached 331 mg/g[97]. The PA functionalized MnO2@GO were capable of electro-adsorbing and removing 92 % of uranyl, with an adsorption capacity of 636 mg/g[98]. The PDA functionalized MoS2 achieved 81.0% uranyl extraction rate and 720.15 mg/g adsorption capacity at 1.20 V due to PDA enhancing electrode hydrophilicity and selectively to uranyl ions[2].

Ye et al.[99] utilized an electrochemical extraction approach to recover uranyl from uranium ore wastewater, and systematically investigated the effects of applied voltage, coexisting ions, initial uranyl concentration, ionic strength, and solution pH on U(VI) extraction efficiency. The highest uranyl removal efficiency was achieved at pH 5, which was attributed to the interplay between the material's surface properties and uranyl speciation (Fig. 8d). As shown in Fig. 8e, the speciation of U(VI) in solution is strongly dependent on the pH value. Under acidic conditions, uranyl predominantly exists as UO2SO4, UO22+ and UO2(SO4)22−, whereas in alkaline environments, the dominant forms shift to (UO2)2CO3(OH)−, and UO2(CO3)34−. Figure 8f demonstrates that carbon materials constitute the principal category utilized for electrochemical uranyl extraction, whereas MXenes and amidoxime-functionalized materials also play significant roles due to their tailored surface properties and electrochemical efficiency. In particular, Ti3C2Tx MXene achieved the uranyl extraction capacity of 4,921 mg/g and the uranyl extraction efficiency of 98.4% in uranium-containing wastewater, attributed to its versatile surface chemistry, good electronegativity, and abundant active sorption sites[100].

Electrochemical extraction of uranyl in seawater

-

The effective extraction of uranyl from seawater, which contains 4.5 billion tons—1,000 times more than terrestrial reserves—addresses a critical need in the nuclear industry to tackle energy and climate change challenges[101]. The low concentration of uranyl (3 ppb), high salinity (3.2%–4.0%), highly stable UO2(CO3)34−, UO2(CO3)22− complexes, microorganisms, and coexisting metal ions (e.g., Ca, Co, Fe, Pb, Ba, and V) are major obstacles in the process of extracting uranyl from seawater[102]. Natural seawater is typically alkaline and rich in coexisting ions. A sample of real seawater (8 mg/L) contains the following major ionic constituents: SO42− (2,400 mg/L), Cl− (8,000 mg/L), K+ (723.9 mg/L), Ca2+ (400.6 mg/L), Mg2+ (1,038.8 mg/L), Na+ (8,873.2 mg/L), and trace elements[103]. The complex saline environment of seawater and the low concentration of uranium necessitate the development of highly efficient materials for uranyl extraction via electrochemical methods.

Tian et al. synthesized cyanide-modified UiO-66 attached to GO/cellulose aerogel composites (UiO-66-CN/GCA) and employed an electro-sorption process for the efficient capture of uranyl from seawater. At an applied voltage of 1.2 V, the extraction capacity of UiO-66-CN/GCA reached 3,092.3 mg/g. In natural seawater, while the physicochemical adsorption capacity of UiO-66-CN/GCA was 14.9 mg/g over 28 d, its electro-adsorption capacity for uranyl reached 110.1 mg/g within 24 h[104]. Zhang et al.[105] inserted redox-active poly(2,5-dihydroxy-1,4-benzoquinone) into the channels of a COF and denoted it as MICOF-14 (Fig. 8g). The C=O group on the benzoquinone can be converted to an adjacent phenoxy anion, which then coordinates with the N and O atoms within the COF channels, thereby achieving selective binding of uranyl ions. The uranyl extraction capacity of MICOF-14 was 380.4 mg/g in the presence of coexisting metal ions such as Cd2+, Ca2+, Zn2+, Cu2+, Ni2+, Mg2+, VO2+, K+, and Na+ (Fig. 8h). The removal efficiency of U(VI) was 99.6% at the applied voltage of −1.3 V within 6 h, and the uranyl concentration reduced to 3 μg/L (Fig. 8i). To achieve efficient electrochemical reduction of uranyl from seawater, Tang et al.[106] synthesized S-terminated MoS2 nanosheets. These nanosheets demonstrated a considerable extraction capacity of 1,823 mg/g for uranyl at the voltage of −3 V due to the abundant active S-edge sites. Nano-reduced iron (NRI) electrode realized high uranyl adsorption capacity of 452 mg/g and extraction efficiency of 99.1% under the voltage of 0.1 V in seawater by electrochemically mediated FeIII/FeII redox method, respectively[68]. The CoMoOS in Ni3S2 fiber electrode exhibited uranyl extraction capacity of 2.65 mg/g/d for electrochemical extraction from real seawater due to the coordination-reduction interface[107]. The boron-doped copper coupled with surface phosphate ions achieved a uranyl extraction capacity of 2.1 mg/g/d in seawater. This enhanced performance is attributed to the presence of B atoms, which reduced the negative charge density on surface Cu atoms and increased it on outer O atoms of the PO43− groups, thereby strengthening both O–Cu and U–O interactions to promote uranyl binding[108].

-

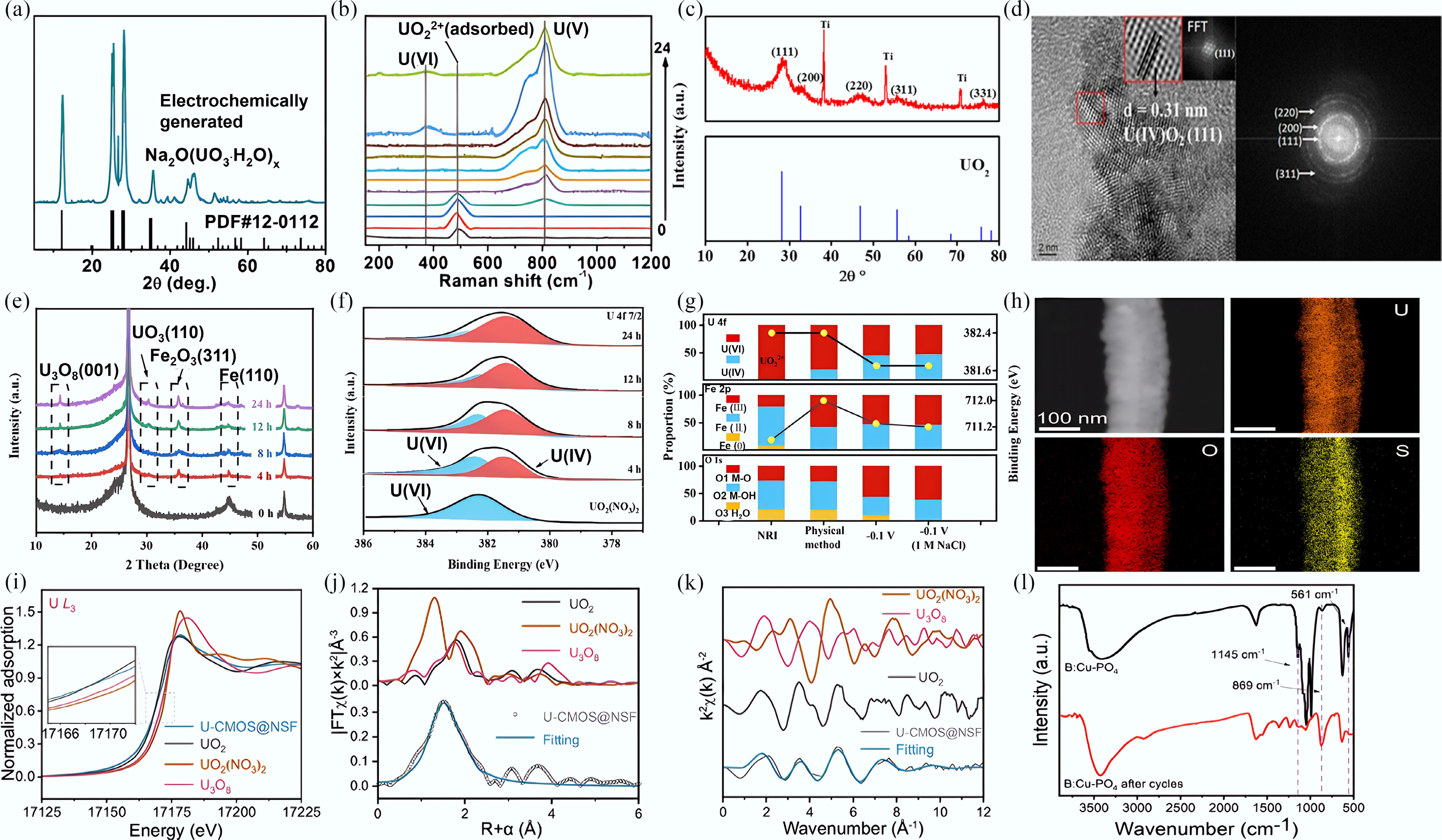

Analyzing and identifying the valence state, morphology, and phase of the solid products resulting from electrochemical uranyl extraction is crucial for validating its underlying electrochemical mechanism. The electrochemically extracted products were characterized using ex situ methods, such as X-ray diffraction (XRD), Fourier infrared transform spectra (FT-IR), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), X-ray adsorption fine spectroscopy (XAFS), and in situ methods (e.g., Raman spectra and XPS).

The XRD patterns offer definitive evidence of the crystalline phases and underlying crystal structure of the obtained products. The solid product of Na2O(UO3·H2O)x was obtained by Liu et al., as shown in Fig. 9a. Raman spectroscopy was employed to verify the vibrational features of the obtained products and to confirm the formation of characteristic U–O bonding as well as the valence state of the uranium species. Initially, prior to electrochemical treatment, a distinct peak for uranyl ions appeared at 489 cm−1. Following the application of voltage, the peak intensity of uranyl gradually decreased, concomitant with the emergence of a U(V) peak at 810 cm−1. A new peak at 374 cm−1 emerged in the spectra at 240 s, which was attributed to the oxidation of U(V) to U(VI) along with Na+ (Fig. 9b)[72]. The reduced uranium product readily oxidizes in air, making the direct acquisition of uranium dioxide (UO2) products rarely reported. Liu et al. utilized Ti electrodes for uranyl extraction from groundwater, performing their electrochemical experiments inside an anaerobic glove box to avoid product oxidation. The morphology and microstructure of the extracted uranyl products were investigated using SEM and TEM. The XRD patterns of the product (Fig. 9c) closely matched the corresponding standard reference patterns, and its crystalline morphology was consistent with the (111) facet of UO2 (Fig. 9d)[67]. The uranyl extraction products using the NRI electrode were analyzed by Quasi-operando XRD and XPS spectra. With the progression of the electrochemical reaction, the main diffraction peak of the NRI electrode at 44.99° weakened, and new diffraction peaks for U3O8, UO3, and Fe2O3 began to appear and intensify (Fig. 9e). The XPS was performed to determine the valence state in the extracted products. An increase in electrochemical extraction time led to a gradual decrease in U(VI) contents and a concomitant increase in U(IV) contents (Fig. 9f). Compared to physical adsorption, electrochemically treated electrode displayed significantly higher U(IV), Fe(II), and M-O contents and significantly lower Fe(0), and M-OH contents. These results suggest that the electrochemical method effectively accelerates the reduction of uranyl and promotes the regeneration of Fe(II) active sites (Fig. 9g)[68]. The uranyl products were further characterized using EDS, XAFS, and FT-IR to comprehensively determine their elemental composition, uranium valence states, local coordination environment, and characteristic U–O bonding features. The EDS mappings in Fig. 9h verified the uniform distribution of O and U elements across the Ni3S2 fiber with polyoxometalate CoMo6-derived amorphous CoMoOS layer (CMOS@NSF) electrode surface. The U L3-edge X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectrum revealed a notable divergence in the absorption edge of the products from those of U3O8 and UO2(NO3)2, with a strong similarity to the peaks of UO2 (Fig. 9i). The fitting curve for the products exhibited strong similarity to the R-space and K-space data curves obtained for standard UO2 (Fig. 9j & k)[107]. Figure 9l shows the FTIR spectrum after electrochemical extraction, in which the emergence of a new peak at 869 cm−1 clearly confirms the formation of O=U=O bonds corresponding to uranium oxide species on the electrode surface. The sustained integrity of the stretching vibration peak of the material's PO4 groups further confirms its stability[108].

Figure 9.

(a) XRD patterns of the electrochemical products. (b) Situ Raman spectra of the electrochemical products[72]. (c) XRD patterns of UO2 on the surface of the electrode. (d) HR-TEM image and SAED pattern of UO2[67]. (e) XRD patterns of NRI before and after different uranyl extraction time. (f) Quasi-operando XPS spectra of U 4f7/2 for NRI/CP before and after different uranyl extraction time. (g) Contents of the oxygen species and different valence states of the Fe and U(VI) by both physical method (24 h), and electrochemical method (0.1 V, 24 h) in 20 mg/L UO2(NO3)2 solution[68]. (h) EDS mappings of CMOS@NSF after electrochemical uranyl extraction. (i) The U L3-edge XANES spectra of the black product. Inset: magnified pre-edge XANES region. (j) Comparison of R-space data and best-fit lines for the products. (k) Corresponding K-space fitting curves for the products[107]. (l) FTIR spectra of the electrode before and after uranyl extraction[108].

-

The electrochemical method provides a high selectivity, efficiency, environmental friendliness and sustainability technique for uranyl extraction and removal using an electrical potential, which can potentially reduce environmental impact and promote the advancement of the nuclear fuel cycle to satisfy growing global energy needs. This review examines various electrode materials including powder-based and self-supporting electrode materials in electro-adsorption, electrocatalysis, and photo-electrocatalysis for uranyl extraction from wastewater and seawater. The underlying principles, electrode materials, and mechanisms of uranyl capture via these electrochemical approaches were summarized. The application of electrochemical extraction technologies in fluoride-rich wastewater, uranium mining wastewater, and seawater treatment, along with methods for characterizing the resulting products, was also summarized. While electrochemical uranyl extraction offers distinct advantages, its practical deployment is constrained by the necessity of external power input. Consequently, future progress necessitates a multi-faceted strategy involving the development and integration of innovative technologies alongside electrochemical techniques. Of course, the stability and selectivity of electrode materials remain key challenges in the electrochemical extraction of uranyl. In complex wastewater matrices, the presence of competing ions significantly compromises selectivity for U(VI), often facilitating undesirable redox reactions that impede overall uranyl extraction efficiency. Furthermore, the development of cost-effective electrode materials and electrochemical reaction systems that minimize energy consumption and operational expenditures is essential. Addressing these multifaceted limitations is imperative for the widespread, sustainable, and efficient implementation of electrochemical uranyl recovery strategies.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: all authors contributed to the study conception and design; Juanlong Li and Bin Ma wrote the original draft of the manuscript; Qihang Chen, Bingfang Pang, Xiaoli Tan, and Ming Fang reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable requests.

-

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U2441291, U24B20195 and U23A20105), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2024MS058).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

-

Electrochemical techniques for uranyl extraction from wastewater and seawater.

Advances in powder-based and self-supporting electrode materials.

The mechanism of electrochemical extraction and removal of uranyl.

The challenges of extracting uranyl from wastewater and seawater.

The characterization techniques of extracted uranium products.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Li J, Chen Q, Pang B, Tan X, Fang M, et al. 2026. A critical review of electrochemical strategies for selective uranyl recovery from radioactive wastewater and seawater. Sustainable Carbon Materials 2: e001 doi: 10.48130/scm-0025-0012

A critical review of electrochemical strategies for selective uranyl recovery from radioactive wastewater and seawater

- Received: 02 November 2025

- Revised: 28 November 2025

- Accepted: 17 December 2025

- Published online: 14 January 2026

Abstract: The rapid advancement of nuclear energy and extensive uranium resource exploitation have led to the environmental release of toxic and radioactive uranium, posing serious threats to ecosystems and human health. Thus, efficient and selective extraction of uranyl (U(VI)) from wastewater and seawater is critical for resource sustainability, pollution mitigation, and safe nuclear development. Electrochemical techniques, including electro-adsorption, electrocatalysis, and photo-electrocatalysis, have emerged as promising approaches for uranyl recovery. This review systematically summarizes advances in electrode materials, encompassing powder-based and self-supporting architectures, with an emphasis on preparation, performance, and limitations. Mechanistic insights into electrochemical uranyl extraction are presented, focusing on the principles of electro-adsorption, electrocatalysis, and photo-electrocatalysis, as well as the impact of electrode properties on uranyl extraction efficiency. Key challenges in treating fluoride-rich wastewater, uranium mining wastewater, and seawater are addressed, demonstrating the tailored application of electrochemical strategies in complex environments. Critical characterization techniques for identifying and quantifying extracted uranium products are also reviewed, underscoring the potential of electrochemical approaches for sustainable uranium recovery.

-

Key words:

- Uranyl (U(VI)) extraction /

- Electrochemical techniques /

- Electrode materials /

- Wastewater /

- Seawater