-

Phosphogypsum (PG) is a solid waste residue generated from the treatment of phosphate rock with sulfuric acid during phosphoric acid production. Its primary component is gypsum (CaSO4·2H2O). The fluorides, radionuclides, and heavy metals present in PG pose a risk of environmental pollution[1]. Now, PG is causing environmental risk globally. Approximately 300 million tons of PG are produced worldwide annually[2,3], of which 58% are dumped[4]. In addition, only 14% PG are currently reused. It is worth noting that over 3 billion tons of additional PG stacks have been built globally, which will cause resource waste[5,6]. PG contains approximately 1% P (mainly as the form of insoluble phosphate)[6−9]. Extraction of residual P can mitigate potential nonpoint-source pollution from the PG yard[10]. Meanwhile, it facilitates the utilization of residual P for agricultural purposes[11,12].

Bioextraction refers to the process of dissolving, recovering, or extracting valuable substances from raw materials by using organisms (primarily microorganisms, such as bacteria and fungi) or their metabolic products (such as organic acids and enzymes)[13]. Bioextraction aims to achieve optimal energy utilization through biotechnology[13,14]. This technology is considered as more environmentally friendly than chemical technology[15]. Bioextraction of sulfur and iron from waterlogged archeological wood by Thiobacillus denitrificans has been successfully performed. Bioextraction showed higher Fe extraction efficiency (65.1%) than chemical extraction (6.6%) of archaeological oak wood[16]. Similarly, iron-oxidizing bacteria and sulfur-oxidizing bacteria have been effectively employed in microbial-mediated copper bioextraction[17,18]. This strategy has been widely implemented for copper recovery from mining wastes and low-grade ores[19]. In the field of agriculture, traditional phosphate fertilizers pose environmental concerns, including eutrophication of adjacent water bodies due to low utilization rates, soil acidification resulting from the application of high-concentration phosphate fertilizers, and the depletion of phosphate rock resources driven by phosphate fertilizer production[20]. With respect to chemical phosphate fertilizers, fertilizers with the addition of functional microorganisms offer advantages such as pollution-free operation, high nutrient utilization efficiency, and alignment with the appeal of sustainable development[21].

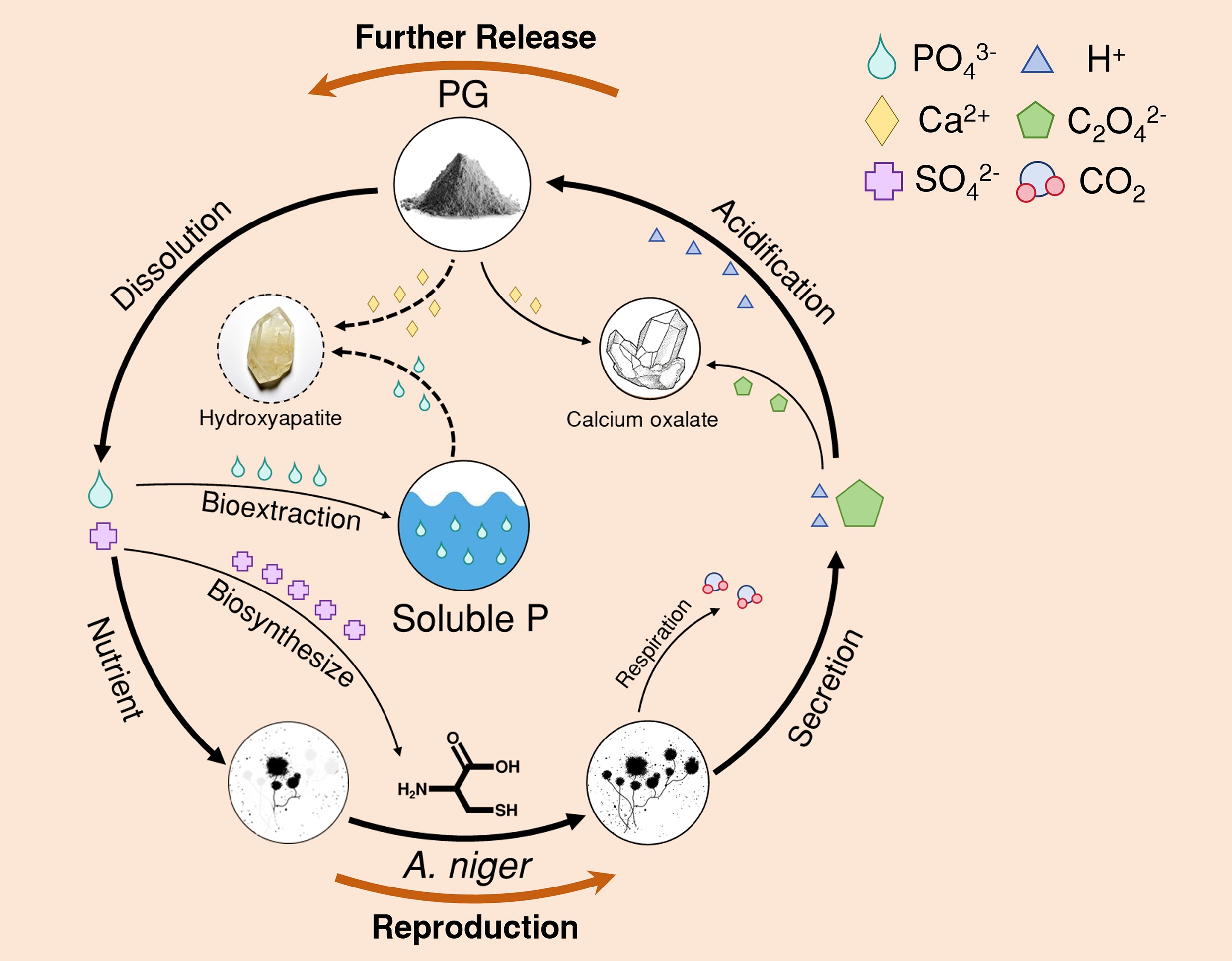

Bioextraction of P (BEP) refers to the use of phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms (PSM) to convert P from an unavailable to an available form[22,23]. Phosphate-solubilizing fungi (PSF) secrete a wider range of organic acids (e.g., oxalic, citric, and gluconic acids) at higher production levels[24,25]. In addition, most PSF remain active under extreme drought or high-metal-concentration environments[26,27]. The excessive Ca2+ from PG can inhibit P dissolution by reducing its availability[28]. Organic acids secreted by microorganisms can substantially dissolve P[29−31], presumably by chelating Ca2+. Meanwhile, the abundant SO42− from PG serves as an S source, providing the S element for biosynthesis within PSM cells[32]. The BEP approach is cost-effective and sustainable[33−36].

Aspergillus niger (A. niger) is one of the highly efficient PSF[37,38]. It is a filamentous fungus whose hyphae can enter gaps between mineral particles to facilitate nutrient uptake[39]. A. niger itself requires P for the synthesis of essential biomolecules such as ATP and cell wall phospholipids[40]. A. niger mainly secretes oxalic acid and citric acid to dissolve insoluble phosphate[41,42]. The secretion abundance of oxalic acid and citric acid depends on the bioactivity of A. niger during incubation, which determines the efficiency of BEP[37,43].

This study aimed to evaluate the influence of gypsum on the BEP efficiency of PG by A. niger. The secondary minerals formed during incubation, the morphology of the fungal-mineral interaction, and the elemental distribution within fungal structures were studied.

-

The PG used in this experiment was collected from Fuquan City, Guizhou Province, China. PG was analyzed using a wavelength-dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (XRF).

A. niger (Accession No. M 2023240) was obtained from the China Center for Type Culture Collection (CCTCC). The information on A. niger in this experiment can be found in our previous study[44]. Before inoculation, the fungal spore suspension was thawed at 28 °C. The activation of A. niger was performed using Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) medium.

A. niger incubation

-

The modified Pikovskaya Inorganic Phosphorus (PVK) medium employed in this study was formulated without any P source, while retaining the addition of 10.0 g dextrose, 0.03 g FeSO4·7H2O, 0.03 g MgSO4·7H2O, 0.3 g NaCl, 0.3 g KCl, 0.5 g (NH4)2SO4, 0.03 g MnSO4·7H2O, and 1,000 mL ultrapure water[45].

For strain activation, A. niger spores were inoculated onto Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) medium on a clean bench. The spore concentration was formed by expanding incubation at 28 °C for 6 d. Then, the medium surface was washed with sterile water on a clean bench, and the spores were carefully scraped off with a sterile inoculation ring to obtain a spore suspension. Finally, three layers of sterile gauze were used to filter the spore suspensions to remove broken mycelial fragments. Spore concentration was calculated with a blood cell counting plate, and the spore suspension was diluted to 107 cfu/mL with 0.85% sterile saline. For the incubation, serum bottles (150 mL) were filled with 50 mL of modified PVK medium. One mL of A. niger spore suspension was inoculated into a medium bottle with different P levels. Five experimental treatments were established, i.e., Control (0.25 g Ca3(PO4)2 as P source), PFree (no P source), LPG (0.1 g PG as P source), MPG (0.5 g PG as P source), and HPG (1.0 g PG as P source). Each treatment was performed in triplicate.

A parallel experiment was set to investigate the BEP efficiency for A. niger. The incubation periods were set at 6, 10, and 15 d, respectively. For these three incubation periods, six treatments were set up, i.e., 6dPG, 6dPG + ANG, 10dPG, 10dPG + ANG, 15dPG, 15dPG + ANG, respectively (ANG represents the treatment in which was inoculated A. niger). Each treatment consisted of 50 mL of modified PVK medium and 1.0 g PG. The incubation conditions were identical to those in the above experiment. Each treatment was also performed in triplicate.

Sample preparation and chemical property analysis

-

After 6 d incubation, the serum bottles were filled with high-purity nitrogen gas (for 5 min) using a nitrogen evaporator (JH-NK200-1B). Then, the serum bottle was capped with a sealed stopper, and A. niger was incubated again for 0.5 h (28 °C, 180 rpm). Finally, after mixing the gas in the serum bottle with a syringe, 10 mL of the mixed gas was extracted for testing CO2 emissions. In addition, the medium was filtered by using a 0.22-μm polyethersulfone (PES) membrane filter. Subsequently, pH values, total organic carbon (TOC), P concentrations, acid phosphatase activity (ACP), and oxalic acid concentration of the filtrate were measured.

After measuring the P concentrations, P extraction efficiencies were calculated according to the following formula:

$ {\eta }_{P}=\dfrac{{C}_{R}}{{C}_{T}}\times 100{\text{%}} $ where, ηP refers to the efficiency of BEP from the corresponding treatment; the CR (mg/L) refers to the P concentration obtained by the ICP-OES test in the filtrate of the corresponding treatment; the CT refers to the total P concentration of the corresponding treatment, which is the P concentration obtained by assuming that all P in the system is dissolved.

The solid phase obtained after filtration was dried in an oven at 65 °C, then weighed to determine the biomass of A. niger. After drying, the solid phase was determined by attenuated total reflection infrared spectroscopy (ATR-IR). Meanwhile, another round of the same incubation experiment was performed. The filtered solid phase was placed in a 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution for 12 h (25 °C). Then, a portion of the solid phase from the HPG treatment was embedded in resin and sectioned into 200 nm-thick slices for nanoscale secondary ion mass spectrometry (NanoSIMS) analysis. The remaining solid phase was dried in a vacuum freeze-dryer (Genscience Instrument Pro-4055, Nanjing, China). After drying, it was characterized by scanning electron microscopy-energy dispersive spectroscopy (SEM-EDS).

GWB modeling and data analyses

-

The Geochemist's® Workbench (GWB Version 12, USA) was applied to simulate the mineralization of Fe and the formation of CaC2O4[45]. The concentrations of HPO42− and PO43− were based on ICP-OES data.

Instrumentation

-

PG was analyzed by XRF (Thermo Fisher ARL Perform' X 4200). The effective diameter of the XRF analysis was 25 mm. CO2 was measured by gas chromatography (GC) (Agilent 7890). The pH values of the filtrate were measured using a Mettler pH meter (Pro-ISM-IP67). The TOC of the filtrate was measured using a total organic carbon and nitrogen analyzer (Multi N/C3100). Concentrations of P were measured by ICP-OES (Optima 8000). Acid phosphatase (ACP) activity of the filtrate was measured with an acid phosphatase kit (Cominbio, Suzhou, China).

Concentrations of oxalic acid were measured by HPLC (Agilent 1200). The chromatographic column was SB-Aq (4.6 mm × 250 mm). The mobile phase consisted of 0.25% KH2PO4 buffer (pH 2.80) and methanol; the volume ratio was 99:1, the flow rate was 1 mL/min, the sample size was 20 μL, the column temperature was 30 °C, and the detection wavelength was 210 nm.

The infrared spectra were acquired using a Nicolet iS5 FTIR spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific Inc.). Data collection was performed using OMNIC software (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Madison, USA) with the following parameters: spectral range of 500–2,000 cm−1, 16 cumulative scans, and 4 cm−1 spectral resolution for each sample.

Elemental mapping was conducted using a NanoSIMS 50 analytical system (Cameca, Courbevoie, France). The hyphal pellets of A. niger were sectioned into semi-thin slices of 200 nm. Then, they were mounted on 10 mm-diameter silicon wafers. The microbial section specimens were continuously bombarded with a cesium ion (Cs+) beam, inducing sputtering of secondary ions from the surface layers. After energy-based sorting in the electrostatic sector, these liberated ions were separated in a mass spectrometer based on their charge-to-mass ratios. The imaging protocol employed a dwell time of 1–3 ms/pixel and an image resolution of 512 × 512 pixels. Finally, the spatial mass distribution maps of 12C14N− (characterizing nitrogen), 31P− and 32S− were produced.

SEM imaging was conducted using a Carl Zeiss Supra 55 system operated at 5–15 kV accelerating voltage. Before imaging, all samples were gold-sputtered for 5 min to minimize surface charging and enhance image quality. The semi-quantitative analysis was performed using an Oxford Aztec X-Max 150 energy-dispersive spectrometer (EDS) with a collection time of 90 s.

-

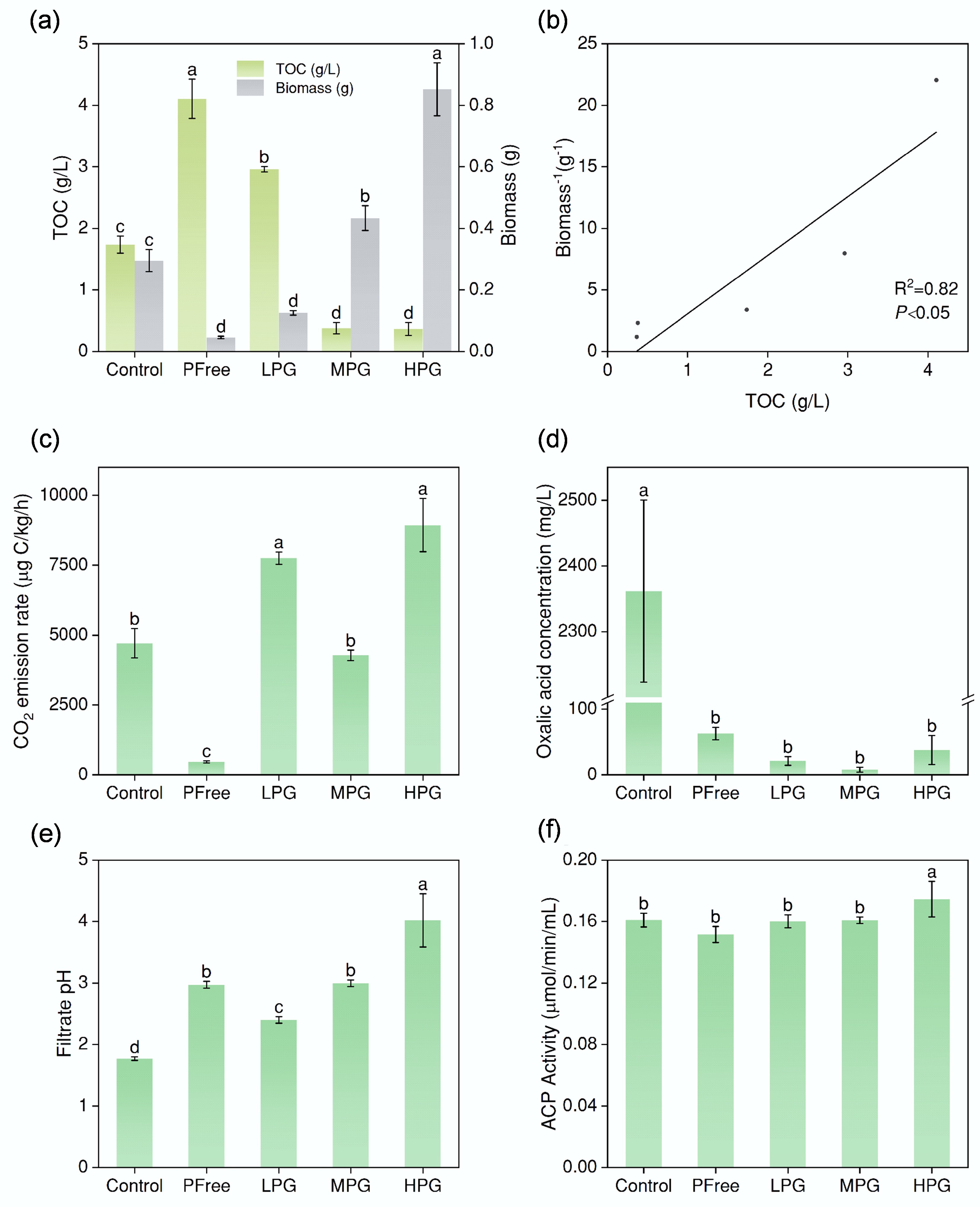

The TOC in Control treatment was 1.74 g/L (Fig. 1a). In contrast, the PFree treatment showed a significantly higher TOC concentration of 4.11 g/L (Fig. 1a). The addition of PG at a low level (LPG treatment) resulted in a lower concentration of 2.96 g/L, which was still higher than that of Control treatment (Fig. 1a). Moreover, the TOC concentrations of the MPG and HPG treatments were significantly lower than that of Control treatment, being 0.38 and 0.36 g/L, respectively (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

Incubation effect of A. niger. (a) Biomass, and TOC content of filtrate after six days of incubation under different treatments. (b) The correlation between TOC values and the reciprocal of biomass. (c) CO2 emission rates of the system. (d) Concentrations of oxalic acid secreted by A. niger. (e) pH values of the filtrate after incubation for six days. (f) acid phosphatase activity of filtrate after incubation for six days. (The lowercase letter labels in the figure indicate significant differences among different treatments. If two treatments contained the same lowercase letter, there was no significant difference between them; otherwise, there was a significant difference).

In the Control treatment, biomass was 0.30 g. The biomass of PFree treatment was as low as 0.05 g (Fig. 1a). In the LPG treatment, biomass was 0.13 g, which was significantly less than that of the Control treatment (Fig. 1a). In the MPG treatment, biomass increased to 0.43 g (Fig. 1a). In the HPG treatment, the biomass reached 0.85 g (Fig. 1a). Moreover, the biomass of A. niger increased with the reduction of TOC concentration, which showed a significant negative correlation (Fig. 1b).

Bioactivity of A. niger

-

The CO2 emission rate of the Control treatment was 4,710 μg C/kg/h (Fig. 1c). In contrast, the respiration intensity of PFree treatment was the lowest, i.e., 470 μg C/kg/h (Fig. 1c). In the LPG treatment, the respiration intensity was 7,750 μg C/kg/h, which was significantly more than the Control treatment (Fig. 1c). In the MPG treatment, the respiration intensity was 4,273 μg C/kg/h, which showed no significant difference from Control treatment. In the HPG treatment, the respiration intensity reached 8,937 μg C/kg/h (Fig. 1c). The respiration intensity of the above A. niger treated with P source was significantly stronger than that of PFree treatment (Fig. 1c).

The oxalic acid concentration in the Control treatment was recorded as 2,362 mg/L (Fig. 1d). When no P source was added during incubation, the PFree treatment showed a significantly lower oxalic acid concentration of 63 mg/L (Fig. 1d), which indicated the limited oxalic acid secretion of A. niger under P restriction. The oxalic acid concentrations in LPG, MPG, and HPG treatments were 21, 8, and 38 mg/L, respectively (Fig. 1d). The solubility of CaSO4·2H2O in pure water (0.264 g/100 g water, room temperature) is approximately 100 times that of Ca3(PO4)2 (0.0025 g/100 g water, room temperature, from ChemBK). Therefore, the incubation system of A. niger with PG resulted in the generation of more CaC2O4 compared with the system of A. niger with Ca3(PO4)2. In the HPLC test, the filtrate did not contain CaC2O4, resulting in extremely low oxalic acid concentrations measured after treatment with PG added.

In the Control treatment, the pH value was 1.8 (Fig. 1e). The pH value in the PFree treatment was 3.0 (Fig. 1e). The pH value significantly increased from 2.4 in the LPG treatment to 3.0 in the MPG treatment, and then increased dramatically to 4.0 in the HPG treatment (Fig. 1e). The pH values from PG treatments were all higher than those in the Control treatment (Fig. 1e).

In HPG treatment, the acid phosphatase activity of the filtrate reached 0.17 μmol/min/mL, which was significantly higher than that of LPG and MPG treatments (Fig. 1f). There was no significant difference in acid phosphatase activity among other treatments except for HPG treatment (Fig. 1f).

BEP efficiency

-

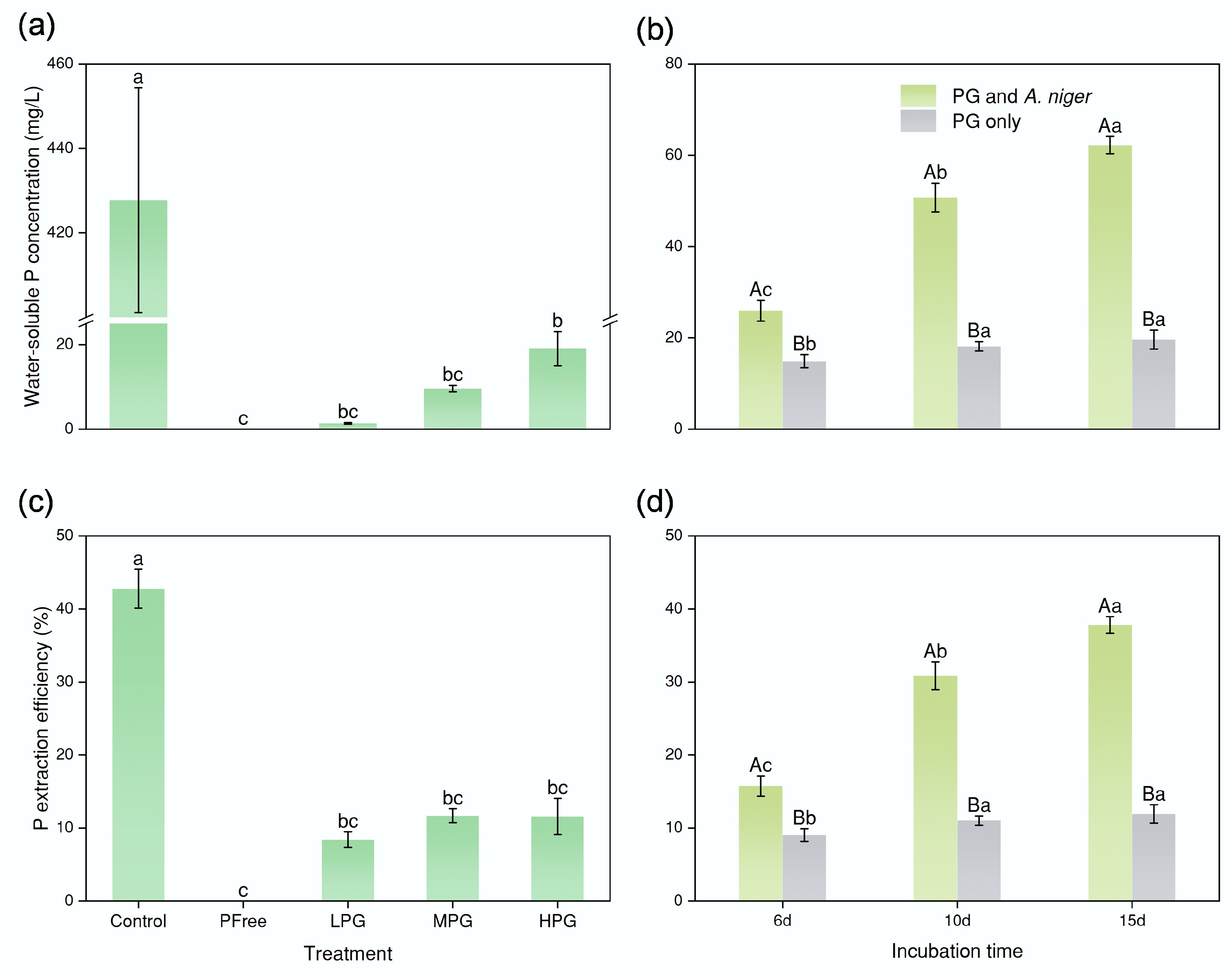

The P content in PG was as low as 0.81% according to XRF results. In the Control treatment, the BEP efficiency from Ca3(PO4)2 by A. niger was 42.78% (Fig. 2c). In LPG, MPG, and HPG treatments, the BEP efficiency from PG by A. niger decreased dramatically to 10% level (8%–12%) (Fig. 2c). This suggested the abundance of added PG showed no significant difference of BEP efficiency.

Figure 2.

Effect of bioextraction of P. (a) and (c) concentrations of water-soluble P and P bioextraction efficiency by A. niger after six days of incubation. (b) and (d) concentrations of water-soluble P and P extraction efficiency after six, 10, and 15 d of incubation, respectively (the P involved in the figure pertained solely to P presented in the solution, excluding P in fungal pellets). In (a) and (c), the lowercase letter labels indicate significant differences among different treatments. If two treatments had the same lowercase letter, there was no significant difference; otherwise, there was a considerable difference. In (b) and (d), the capital letter labels indicate whether there was a substantial difference between the treatments PG only or PG and A. niger at the same incubation time. The lowercase letters indicate significant differences among incubation times within each treatment (PG only or PG and A. niger). The method for determining substantial differences was consistent with the above.

The incubation time, however, showed evident changes in BEP efficiency. The BEP efficiency significantly increased from 15.75% (6dPG + ANG treatment) to 30.84% (10dPG + ANG treatment). Finally, it was elevated to 37.81% for the 15dPG + ANG treatment (Fig. 2d). Without A. niger, the P dissolution efficiencies maintained at 10%, i.e., 9% for 6dPG treatment, 11% for 10dPG treatment, and 12% for the 15dPG treatment (Fig. 2d). The role of A. niger in the process of P dissolution in PG was significant.

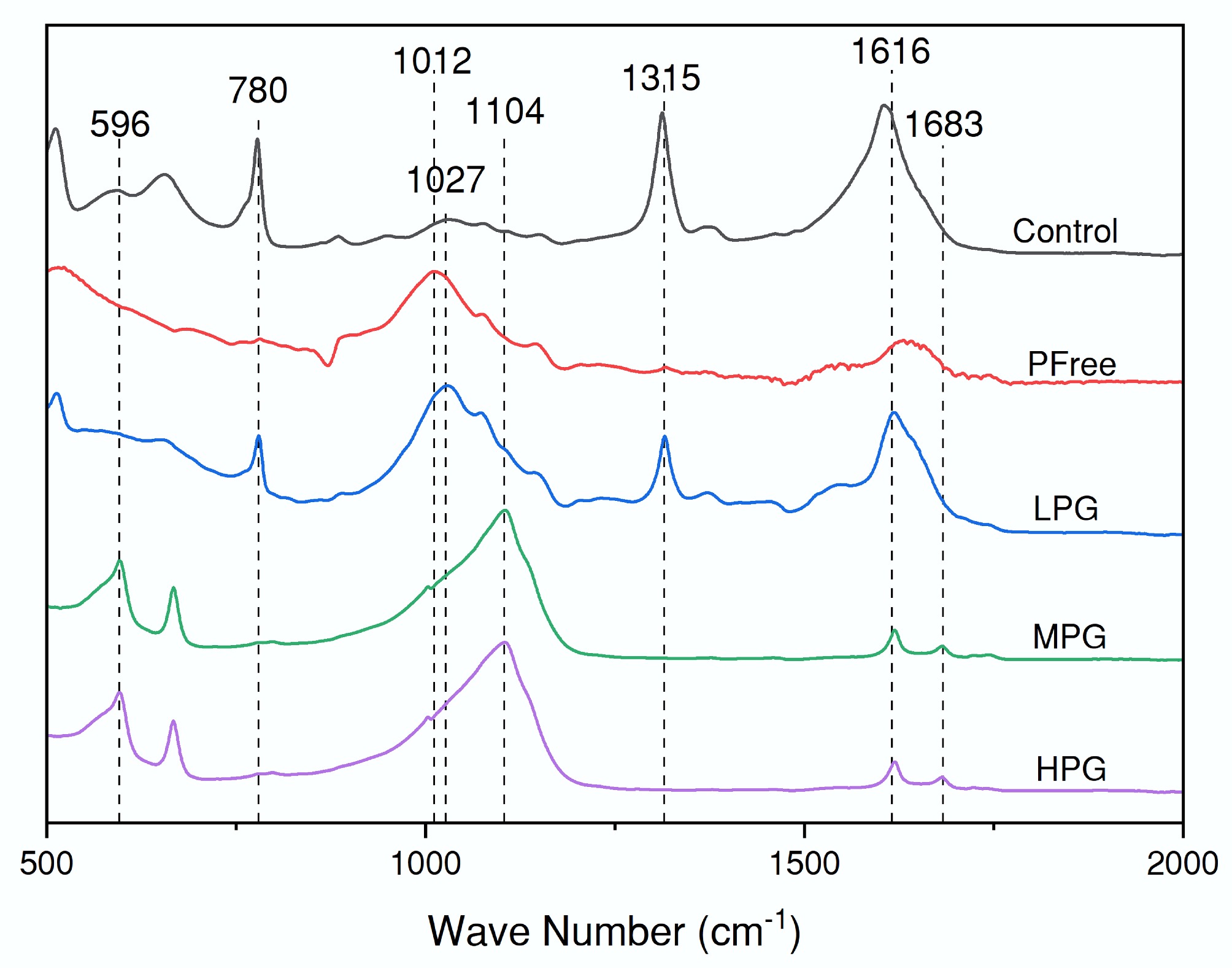

Functional groups analysis of ATR-IR

-

In the ATR-IR spectra (Fig. 3), the absorption band at 596 cm−1 was characteristic of phosphate P-O vibrational modes[46]. This peak displayed maximal intensity in MPG and HPG treatments (Fig. 3). The absorption band at 780 cm−1 was attributed to P-O vibration based on HPO42−. This peak was prominent in both Control and LPG treatments (but with higher intensity in the Control treatment) (Fig. 3). The absorption band at 1,012 cm−1 was assigned to C–O and C–C vibrations from microbial polysaccharides[47,48], which was prominent in PFree treatment (Fig. 3). The 1,027 cm−1 band represented ν1 and ν3 P-O vibration of PO43− (Fig. 3)[49,50]. Compared with the Control treatment, the intensity of this peak was significantly enhanced in the LPG treatments (Fig. 3). At 1,104 cm−1, the spectrum exhibited a mixed vibrational mode resulting from the combination of P-O (for PO43−) and S-O (for SO42−)[51]. The intensity distribution of this peak was similar to that of the 596 cm−1 peak (Fig. 3). As the mass of PG increased, there was more SO42− in the system, and the intensity of this peak got stronger (Fig. 3). The absorption band at 1,315 cm−1 represented symmetric stretching vibrations of C-O from C2O42− while that at 1,616 cm−1 represented the asymmetric stretching vibrations from HC2O4−[52]. Both peaks were characteristic of oxalic acid (Fig. 3). The 1,683 cm−1 peak represented the C=O stretching vibration (Fig. 3)[53]. The intensity of the three peaks above in the spectra of Control and LPG treatments was higher than that in MPG and HPG treatments (Fig. 3). When the mass of PG reached 0.5 g, the peaks of oxalic acid functional groups were masked by the peak of S-O vibration in PG (Fig. 3).

NanoSIMS, SEM-EDS, and GWB analysis

-

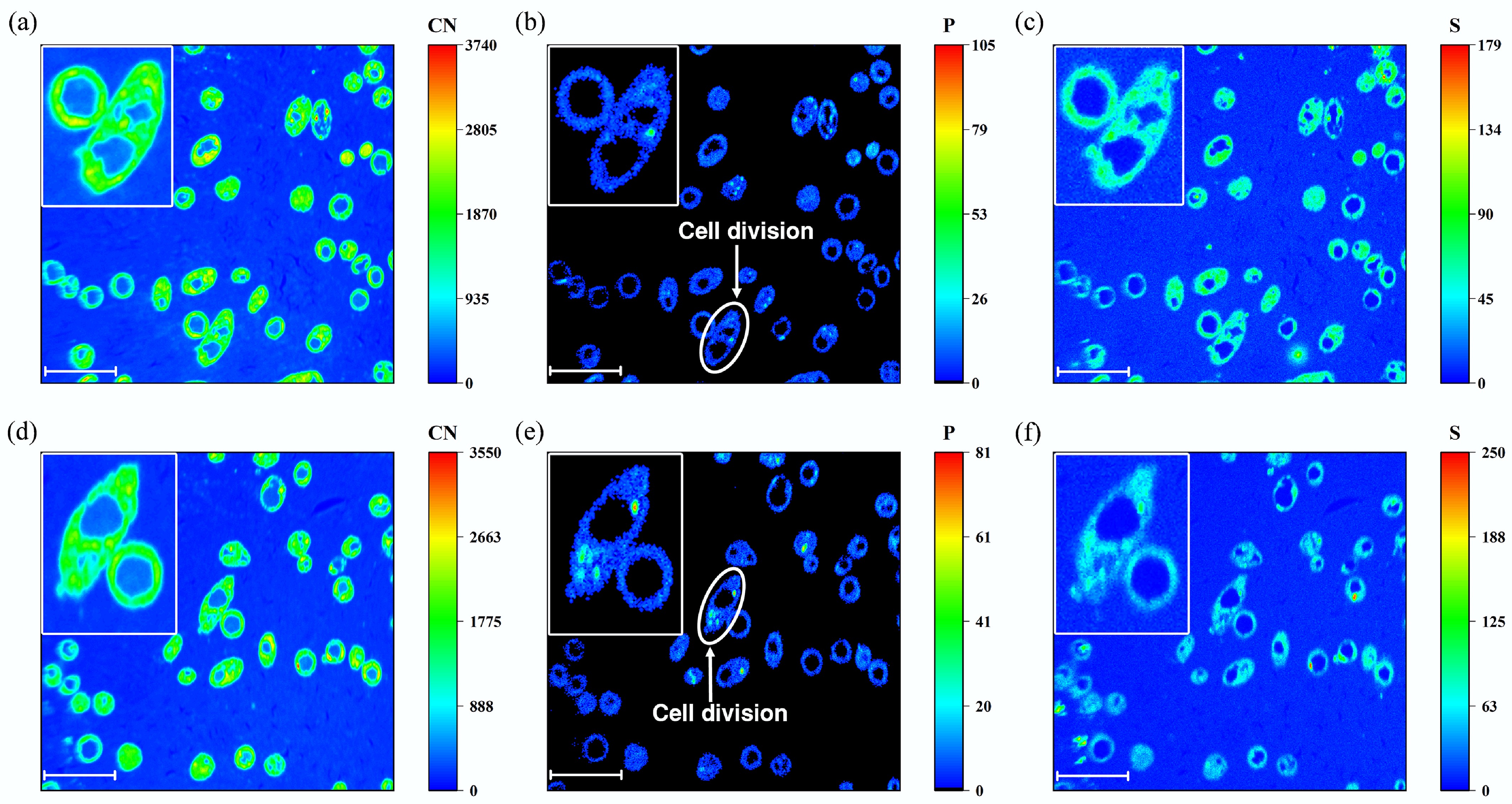

Signals from the CN element in the NanoSIMS images were used to locate areas of biological composition (Fig. 4a, d). The signal of the P element further highlighted the cellular structure of A. niger (Fig. 4b, e), which was highly coincident with that of the CN element. P maps indicated that most of the P in PG was within A. niger cells for fungus growth during incubation (Fig. 4b, e)[44]. Meanwhile, enrichment of the P element was observed in specific A. niger cells (Fig. 4b, e), indicating cell division. In addition, the signal of the S element displayed the basal sulfur distribution, which can mainly be ascribed to sulfur-containing proteins. S maps indicated that the abundant SO42− in PG could be absorbed by A. niger for the synthesis of cellular proteins (Fig. 4e, f).

Figure 4.

NanoSIMS images of High PG treatment after 6 days of incubation. (a) and (d) CN element distribution. (b) and (e) P element distribution. (c) and (f) S element distribution. (a)−(c) were from the same region, while figures (d)−(f) were from another region. The scale bar of all the figures was 10 μm.

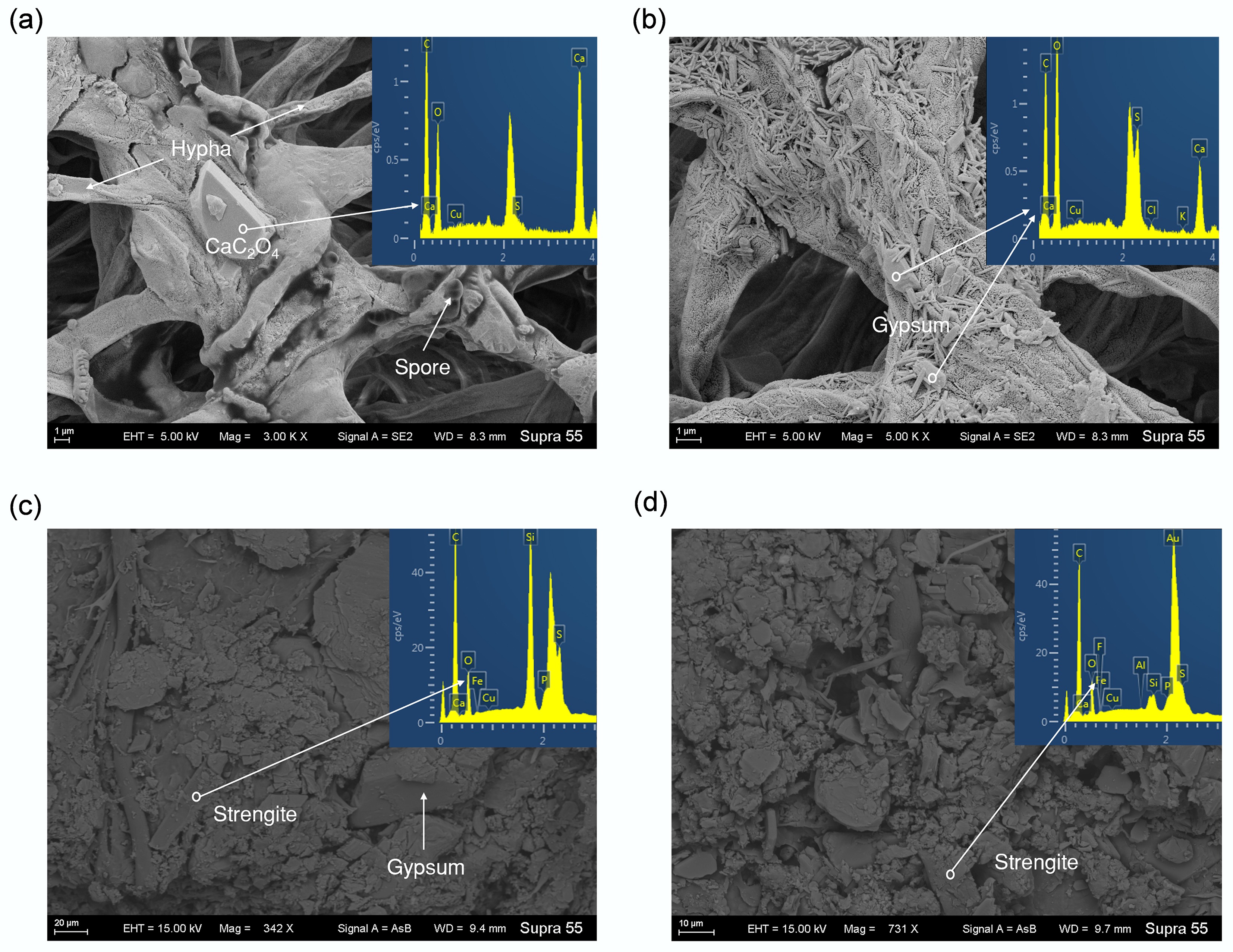

The contents of Ca and Fe in the PG were 32.19 and 0.49 wt%, respectively, based on XRF analysis. The solid phases obtained from LPG, MPG, and HPG treatments were observed by SEM (Fig. 5). SEM image and EDS result confirmed the formation of CaC2O4, which was tightly interacted by hyphae of A. niger (Fig. 5a). During incubation, oxalic acid secreted by A. niger interacted with the CaSO4 adsorbed by its hyphae (Fig. 5b). Then, the C2O42− ionized from oxalic acid replaced the SO42− in CaSO4, resulting in the formation of CaC2O4 (Fig. 5a). Meanwhile, as the P in PG slowly dissolved into the solution, Fe in the solution was mineralized to strengite (Fig. 5c, d).

Figure 5.

SEM and EDS images of minerals formed during incubation. (a) Calcium oxalate from Low PG treatment. (b) Gypsum particles adsorbed by A. niger hyphae from High PG treatment. (c) and (d) Strengite from Moderate PG treatment.

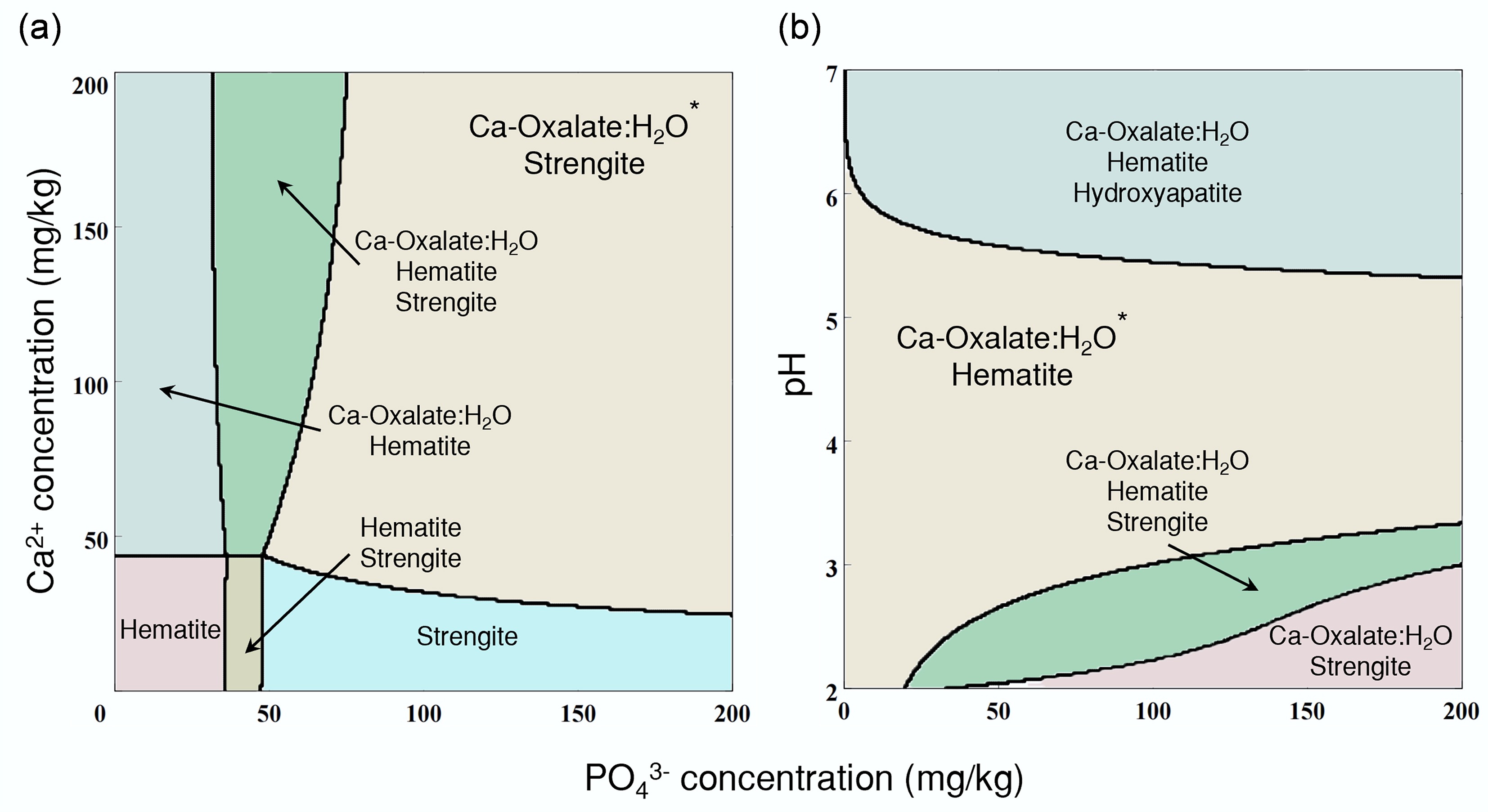

GWB simulation revealed that with the increase of pH, PO43− tended to combine with Ca2+ and then mineralized into hydroxylapatite (Fig. 6b). Meanwhile, the abundance of Ca2+ and C2O42− in the solution induced substantial precipitation of CaC2O4 (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Simulation of the A. niger-phosphogypsum interaction system. (a) Geochemical simulated mineralization under different concentrations of PO43− and Ca2+ by the GWB Act2 module. (b) Geochemical simulated mineralization under different concentrations of PO43−, and different pH by the GWB Act2 module.

-

The residual P in PG is the portion that remained unextracted during sulfuric acid leaching. This makes re-extraction of P usually difficult and of low-efficiency. The secretion of oxalic acid has been reported to promote P release from insoluble phosphates with high efficiency. The BEP efficiency in this study confirmed that biogenic oxalic acid is fully capable of dissolving the residual P within PG (see Fig. 2). Moreover, as a typical filamentous fungi, A. niger can capture and wrap dispersed PG particles in the medium through its hyphal network during the incubation process (see Fig. 5b)[54]. Then, fungal hyphae can extend the distribution of oxalic acid on PG particles[55]. These two pathways together would provide a favorable microenvironment for PG dissolution. In agriculture, the hyphal network of A. niger can extend into various soil micropores and regions inaccessible to plant root systems, thereby expanding the scope of P solubilization in the soil system[56,57].

The BEP efficiency of PG by A. niger reached as high as ~40% for the 15dPG + ANG treatment (see Fig. 2d), which was comparable to its BEP efficiency from pure Ca3(PO4)2 (see Fig. 2c). This result was attributed to the sustainability provided by A. niger during the BEP process. In addition, the extraction efficiency of PG could be further improved by extending the incubation time of A. niger. A portion of the extracted P in solution was utilized for the growth of A. niger and participated in biological metabolic processes (see Fig. 4b, e)[56]. Microorganisms require P uptake for the synthesis of essential biomolecules such as ATP and cell wall phospholipids[40, 58]. The release of P from PG promised the fungal metabolism. Meanwhile, the fungal metabolism ensured the sustainability of the BEP process[59]. Moreover, the P in the biomass of these fungal cells can be easily applied as fertilizer or in the biochemical industry[60].

Traditional chemical extraction methods (e.g., sulfuric acid leaching) indiscriminately dissolve more Ca, Fe, Si, and other minor elements than BEP[61]. However, dissolved Ca tends to recombine with P and re-mineralize into hydroxylapatite (see Fig. 6b). Similarly, Fe3+ demonstrates a distinct propensity to mineralize with PO43− into strengite (see Figs 5c, d, and 6). Both mineralization pathways would significantly reduce the efficiency of P extraction. The dissolution of Si results in the formation of silica gel, which physically hinders contact between sulfuric acid and PG, thereby indirectly impairing P extraction efficiency[62,63]. This can explain why chemical P extraction methods inevitably retain ~1% residual P in PG globally. Conversely, BEP exhibits highly selective P recovery, particularly at low P concentrations. Additionally, the microorganisms specifically target P while minimizing the co-solubility of impurities[64].

The release of P from PG and the metabolism of A. niger may have formed a positive feedback loop. Primarily, the acidity of PG would create a favorable environment for the incubation of A. niger. With the PG addition, the biomass and bioactivity of A. niger were enhanced (see Fig. 1a). Then, A. niger would continuously secrete oxalic acid during incubation. The H+ ionized from oxalic acid provided a more favorable microenvironment for P dissolution. Meanwhile, C2O42− mineralized with Ca2+ to form CaC2O4, thereby reducing the reabsorption of dissolved P by free Ca2+ [42]. Subsequently, the solubilization of P would be enhanced. In addition, the released P would be absorbed by A. niger cells to meet their nutritional requirements (see Fig. 4e)[58]. The abundant SO42− in PG would maintain the positive feedback loop of the BEP process. SO42− was absorbed by A. niger through the sulfate transporter, then reduced to SO32− or S2− via the sulfate assimilation pathway, ultimately synthesizing into sulfur-containing amino acids such as cysteine[32]. PG also contained other nutrients required by microorganisms, such as K (0.8%) and Mg (0.3%), which may be essential during incubation[65]. Such a positive feedback loop would ensure the sustainability of fungal growth and the BEP process.

After bioextraction, the P in the solution existed as PO43−, which is available to plants. Although the P content in PG is relatively low, it is readily soluble due to prior acidulation with sulfuric acid. For plants, the main issue is the low utilization rate of P[54,66]. The biosystem composed of A. niger and PG can be utilized for the production of highly efficient microbial phosphate fertilizers. The hyphae of A. niger can build a bridge between available P and the plant root system, thereby maximizing the utilization efficiency of P[23]. When such a biosystem is applied to the soil, plants will absorb the P released by the fungal hyphae through their root systems[67]. Meanwhile, the plant roots and fungi will also form a positive feedback regulation. The plant root system secretes organic matters (such as phosphatases and amino acid derivatives) to stimulate A. niger to grow more vigorously[68], thereby secreting more organic acids to release insoluble P[69].

-

The presence of PSF A. niger significantly increased the release efficiency of P from PG. The efficiency of BEP increased with increasing incubation time. There might be a positive feedback loop between the incubation of A. niger and the recovery of P from PG. BEP of A. niger provides a broad prospect for the treatment of substantial PG waste and the improvement of the shortage of soil available P in agricultural fields.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Zhenyu Chao: investigation, methodology, validation, writing − original draft, writing − review and editing; Haoxuan Li: writing − original draft, writing − review and editing; Jiakai Ji: writing − original draft, writing − review and editing; Xin Sun: investigation, data curation; Yuhang Sun: investigation, data curation; Meiyue Xu: investigation, data curation; Ying Wang: investigation, data curation; Da Tian: supervision, project administration; Haoming Chen: supervision, project administration; Dan Yu: supervision, project administration; Zhen Li: conceptualization, funding acquisition, writing − review and editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2023YFC3707600), and the Research Fund Program of Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Environmental Pollution Control and Remediation Technology (Grant No. 2023B1212060016).

-

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

-

Oxalic acid secreted by A. niger would preferentially combine with Ca2+ in PG to produce CaC2O4.

The formation of CaC2O4 reduced the reabsorption of P by Ca2+.

SO42− from PG participated in the biosynthesis of sulfur-containing amino acids within the A. niger cells.

High bioactivity of A. niger promoted further bioextraction of P from PG.

The BESP efficiency is over 40% after 15 d of incubation.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Zhenyu Chao, Haoxuan Li, Jiakai Ji

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article. - Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Chao Z, Li H, Ji J, Sun X, Sun Y, et al. 2026. Bioextraction of residual phosphorus from phosphogypsum by phosphate-solubilizing fungus Aspergillus niger. Environmental and Biogeochemical Processes 2: e002 doi: 10.48130/ebp-0025-0018

Bioextraction of residual phosphorus from phosphogypsum by phosphate-solubilizing fungus Aspergillus niger

- Received: 12 September 2025

- Revised: 04 December 2025

- Accepted: 17 December 2025

- Published online: 19 January 2026

Abstract: Phosphogypsum (PG) is a typical solid waste formed during wet-process phosphoric acid production, and it retains a significant amount of residual phosphorus (P). Bioextraction of phosphorus (BEP) applies microorganisms to dissolve P from phosphate minerals. This study aimed to evaluate the influence of gypsum (CaSO4) on the BEP efficiency of PG by Aspergillus niger. After 6 d incubation with the addition of HPG (high dose of PG, 1.0 g), the biomass and respiration of A. niger reached 0.85 g and 8,937 μg C/kg/h, respectively. Meanwhile, the BEP efficiency of A. niger reached ~40% after 15 d of incubation, compared with ~10% in the treatment without the fungus. Given the amount consumed by A. niger, the efficiency should be significantly higher. Moreover, nanoscale secondary ion mass spectrometry (NanoSIMS) imaging showed that P was absorbed by A. niger cells to meet their nutritional requirements. Simulation from Geochemist's® Workbench (GWB) revealed that PO43− tended to combine with Ca2+ and mineralize into hydroxylapatite as pH increased. However, oxalic acid secreted by A. niger would combine with the abundant Ca2+ in PG to produce CaC2O4, thereby reducing the fixation of P by free Ca2+. Furthermore, the SO42− from PG participated in the biosynthesis of sulfur-containing amino acids within the fungal cells. This study revealed the potential of BEP by A. niger for the treatment of solid waste PG.

-

Key words:

- Bioextraction /

- Phosphorus /

- Phosphogypsum /

- Gypsum /

- Aspergillus niger