-

Land plants coexist with diverse microbial pathogens in complex ecosystems, where cuticular waxes play a crucial role in biotic stress resistance[1,2]. Blumeria graminis, an obligate biotrophic pathogen infecting 634 Poaceae species, including wheat and barley[3], is among the top ten most economically significant fungal pathogens globally[4]. This pathogen compromises host photosynthesis through epidermal cell invasion[5], posing considerable threats to both grassland ecosystems and agricultural productivity[6].

The grass-endophyte symbiosis represents a paradigm of sophisticated plant-microbe interactions[7]. Achnatherum inebrians, a foundational species in China's northwestern alpine meadows, demonstrates near-complete colonization (> 98%) by mutualistic Epichloë endophytes in natural populations[8]. Two endophytes have been isolated from A. inebrians plants: E. gansuensis[9] and E. inebrians[10]. The symbiosis of the Epichloë endophyte and A. inebrians increases the tolerance of A. inebrians to biotic stresses, including insect resistance[11] and disease resistance[5], and it also increases plant tolerance to abiotic stresses such as drought[12,13]. However, its regulatory mechanisms on cuticular wax metabolism remain unexplored.

Cuticular wax has been fundamental to the evolutionary success of terrestrial plants, serving critical functions in hydroregulation, biotic defense, and environmental signaling[14]. This hydrophobic barrier minimizes non-stomatal water loss while acting as the primary interface for plant-pathogen interactions[1,15]. Beyond physical protection against microbial penetration, the wax layer functions as a dynamic biochemical platform that both triggers host defense mechanisms and potentially signals pathogenic invasion[16−18]. Compositional analyses reveal substantial interspecific and organ-specific variations in wax profiles[19,20]. In Arabidopsis thaliana, hydrocarbons constitute approximately 50% of total wax across tissues, with secondary alcohols and ketones predominantly localized to reproductive structures[21]. Contrastingly, Camelina sativa demonstrates tissue-specific partitioning, with primary alcohols dominating seed coats (72%–85%) vs ester-triterpene complexes in vegetative organs[22]. Environmental stressors induce measurable metabolic reprogramming, as evidenced by drought treatments increasing total cuticular monomers by 65% and cuticle thickness by 49%, while 150 mM NaCl elevates aliphatic components by 32%–80% without structural modifications[19]. These adaptive responses enhance plant resilience through pathogen exclusion, particulate shedding (including fungal spores < 50 μm), and insect interaction modulation[23]. The integration of physical barrier properties with chemical signaling capabilities positions cuticular wax as a multifunctional interface critical to plant survival under biotic and abiotic challenges.

The molecular mechanisms by which leaf cuticular waxes respond to pathogens are however poorly understood. Therefore, in this study, the aim was to investigate how B. graminis infection influences the total amount of cuticular wax, the relative content of individual wax components, and the biosynthetic pathways of cuticular waxes in Epichloë-infected (E+), and uninfected (E−) A. inebrians leaves. By integrating GC-MS and transcriptomic analyses, the differential expression of wax synthesis-related genes under pathogen stress were further clarified, providing new insights into the role of cuticular wax in endophyte-mediated disease resistance.

-

Seeds of E. gansuensis-colonized (E+), and endophyte-free (E−) A. inebrians were collected in 2019 from the experimental field of the College of Pastoral Agriculture Science and Technology, Yuzhong campus of Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China (104°390 E, 35°890 N, altitude 1,653 m). Seeds were stained with aniline blue, and examined microscopically to determine the presence or absence of Epichloë endophyte. Based on this examination, two seed populations were established: one with 100% infection (E+), and the other with 0% infection (E−). Seeds were stored at 4 °C until further use[24].

The B. graminis spores used for inoculation were obtained from naturally infected A. inebrians leaves collected in the greenhouse at the Yuzhong Campus of Lanzhou University, following the methods of Kou et al.[25]. The conidia were carefully brushed off the A. inebrians leaves with a soft-bristled brush, transferred to a 1.5 mL Eppendorf centrifuge tube, and cooled in a refrigerator at 4 °C. The collected conidia were viewed in suspension under a 40× microscope. The suspension contained only one type of fungal spore, and the shape and size of these spores matched those of B. graminis.

A pot experiment was conducted in a controlled greenhouse at the College of Pastoral Agriculture Science and Technology, Yuzhong Campus of Lanzhou University (Lanzhou, China). For each treatment, three visually uniform and fully developed seeds (E+ or E−, approximately 10 mm in length and 2 mm in width) were sown in individual pots (upper diameter: 12 cm, lower diameter: 10 cm, height: 13.5 cm) containing 250 g of vermiculite sterilized at 180 °C for 2 h. A total of 240 pots were established (120 pots E+ and 120 pots E−). Pots were randomly arranged in the greenhouse under constant environmental conditions (26 ± 2 °C, 42% ± 2% relative humidity), and watered regularly to maintain moist conditions. After the second fully developed leaf emerged, Hoagland's solution was supplied every 7 d.

Pathogen inoculation was performed at the inflorescence stage. From the 240 pots, 200 uniform and healthy plants were selected. Fifty E+ and 50 E− plants were inoculated with B. graminis conidia (pathogen-inoculated plants, P+), while another 50 E+, and 50 E− plants were mock-inoculated with sterilized water (non-inoculated plants, P−). For inoculation, 5 mL of a conidial suspension (2 × 106 spores mL−1) was evenly brushed onto the leaf surface from tip to base using a sterile brush. Control plants received the same treatment with sterilized water. After inoculation, P+ and P− plants were maintained in separate greenhouse compartments under identical growth conditions. Plants were monitored for four weeks after inoculation.

Cuticular wax extraction and chemical analysis

-

Five leaves of A. inebrians were selected for each treatment, and cuticular waxes were extracted following the method described by Zhao et al.[26]. The test leaves were cut into a length of 10 cm, and their width was measured at three randomly selected points. The average value was recorded as w1. A sterilized 10 mL beaker was weighed and recorded as w2. Subsequently, 10 mL of chloroform (Tianjin Guangfu Fine Chemical Research Institute, Tianjin, China) was added to the beaker in a fume hood, and the leaves were completely immersed in chloroform for 45 s at room temperature. The chloroform solution was then removed. After complete volatilization of the solvent, the beaker was reweighed and recorded as w3. The total wax content was calculated according to the following formula:

${\rm{ Total\; wax\;}} \;({\text{μ}}{\rm{g\; cm}}^{-2}) = \dfrac{{w}_{3}-{w}_{2}}{{10\times w}_{2}} $ Five mL of chloroform was poured into the beaker to dissolve the wax in the beaker. Then, 20 µL of n-tetracosane (1 µg·L−1, Aladdin, Shanghai, China) was added as an internal standard and concentrated to 1 mL under nitrogen flow, and transferred to a GC sample vial (1.5 mL), to which 20 µL of N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)-trifluoroacetamide (GC derivatization reagent, ≥ 98.0%, Aladdin, Shanghai, China), and 20 µL of pyridine (standard for GC, > 99.9%, Aladdin, Shanghai, China) were added and heated to 70 °C for 1 h. After derivatization, the mixture was filtered through an organic filter tip (0.45 µm), transferred to a new GC vial, and concentrated again to 0.5 mL under nitrogen for gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis. Chemical analyses were performed using GCMS (GCMS-QP2020, Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan), and a DB-1 MS column (30 m length × 0.25 µm inner diameter × 0.25 µm film thickness; Agilent Technologies Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA). Helium was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.2 mL·min−1. The GC-MS operating parameters were set as follows: inlet temperature, 280 °C; mass spectrometry quadrupole temperature, 150 °C; transfer line temperature, 250 °C; ion source temperature, 230 °C; and mass scan range m·z−1, 50–850. GC was performed at the following temperature settings: 50 °C for 2 min, 40 °C min−1 to 200 °C, 200 °C for 2 min, and 200 °C for 2 min. The oven temperature program was: 50 °C for 2 min, increased at 40 °C min−1 to 200 °C and held for 2 min, then increased at 3 °C min−1 to 320 °C and maintained for 30 min.

Individual wax components were identified by comparison with the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) library, and wax compounds were quantified by integrating peak areas relative to the internal standard.

RNA extraction and transcriptome analysis

-

After four weeks of treatment, three fresh leaves were collected from each of three pots of E+ and E− A. inebrians plants inoculated with B. graminis, as well as from three pots of uninoculated E+ and E− A. inebrians plants. The samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for subsequent RNA extraction and transcriptome sequencing. Total RNA (3 µg per sample) was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The quality and integrity of RNA were evaluated by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and further assessed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

The mRNA-Seq library was prepared with the NEBNext® UltraTM RNA Library Prep Kit from Illumina®. RNA sequencing was performed by the Biomarker Technologies Company (Beijing, China)[25].

High-quality clean reads (= 90.54 Gb) were obtained from the raw reads by removing sequences containing adapters, poly-N sequences, and low-quality sequences. The obtained unigene sequences (in FASTQ format) were used to query specific functions in the following databases: NR (NCBI nonredundant protein sequences); Pfam (protein family); KOG/COG/eggnog (clusters of orthologous groups of proteins); Swiss-Prot (a manually annotated and reviewed protein sequence database); KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes); and GO (Gene Ontology).

Differentially Expressed Gene (DEG) analysis

-

This experiment focused on identifying differentially expressed genes involved in pathways related to cuticular wax synthesis and transport in leaves under three treatments (E−P+, E+P+, and E+P−). The fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM) values were calculated to estimate the expression level of all genes in each sample. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (FDR (false discovery rate) < 0.05, and |log2fold change| ≥ 2) were analyzed via DEseq2_EBseq. Gene Ontology (GO), enrichment and functional annotation of DEGs were implemented via the GOseq R package. The DEGs were also subjected to Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis to identify the major biochemical metabolic pathways and signal transduction pathways.

Statistical analysis

-

Two-way analysis of variance (two-way ANOVA) with SPSS 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to test the effects of Epichloë endophyte and B. graminis treatments on the total wax content, and the relative content of each component in A. inebrians leaves. The least significant difference (LSD) method was applied for multiple comparisons. All values are expressed as mean ± standard error (SE).

-

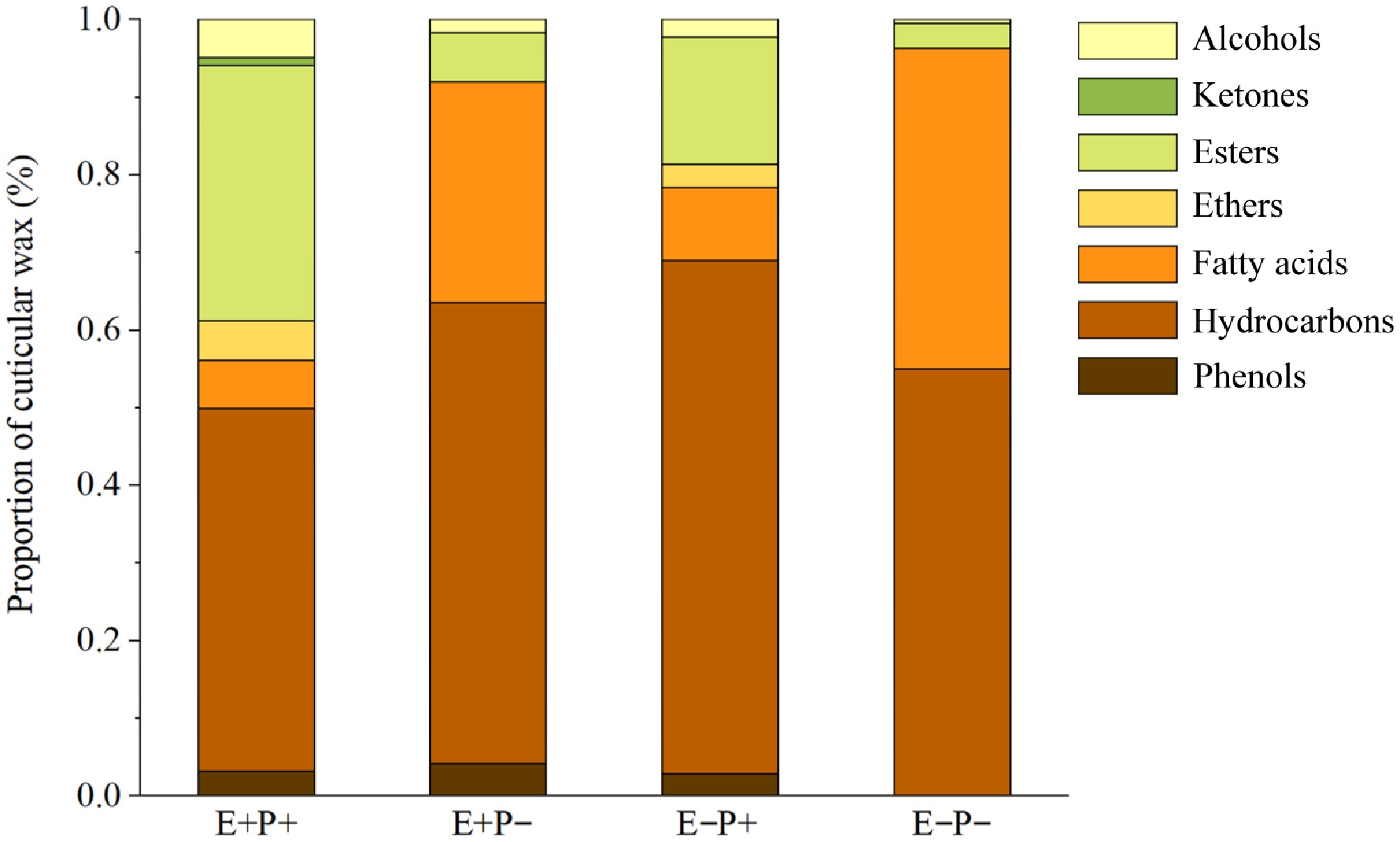

Separation of the cuticular wax composition of A. inebrians leaves via GC-MS revealed that the cuticular wax of A. inebrians leaves consisted of seven types of compounds: alcohols, ketones, esters, ethers, fatty acids, hydrocarbons, and phenols (Supplementary Tables S1−S4), with hydrocarbons, fatty acids, and esters being the most abundant (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Effects of Epichloë endophyte and B. graminis treatments on the composition and proportion of cuticular wax of the leaves of A. inebrians. Note: E+: Epichloë endophyte-infected, E−: Epichloë endophyte-free, P+: pathogen-inoculated, P−: non-inoculated.

Under the E+P+ treatment, the cuticular waxes of A. inebrians leaves consisted of phenols, hydrocarbons, fatty acids, ethers, esters, ketones, and alcohols, with 3.14% phenols, 46.74% hydrocarbons, 6.23% fatty acids, 5.02% ethers, 32.88% esters, 0.99% ketones, and 5.00% alcohols. Under the E−P+ treatment, the cuticular waxes of A. inebrians leaves consisted of phenols, hydrocarbons, fatty acids, ethers, esters, and alcohols, with 2.81% phenols, 66.11% hydrocarbons, 9.43% fatty acids, 2.98% ethers, 16.41% esters, and 2.25% alcohols. Under the E+P− treatment, the cuticular waxes of A. inebrians leaves consisted of phenols, hydrocarbons, fatty acids, esters, and alcohols, with 4.08% phenols, 59.41% hydrocarbons, 28.43% fatty acids, 6.33% esters, and 6.33% alcohols. Under E−P– treatment, the cuticular waxes of A. inebrians leaves consisted of hydrocarbons, fatty acids, esters, and alcohols, of which 54.97% were hydrocarbons, 41.33% were fatty acids, 3.17% were esters, and 0.53% were alcohols (Fig. 1).

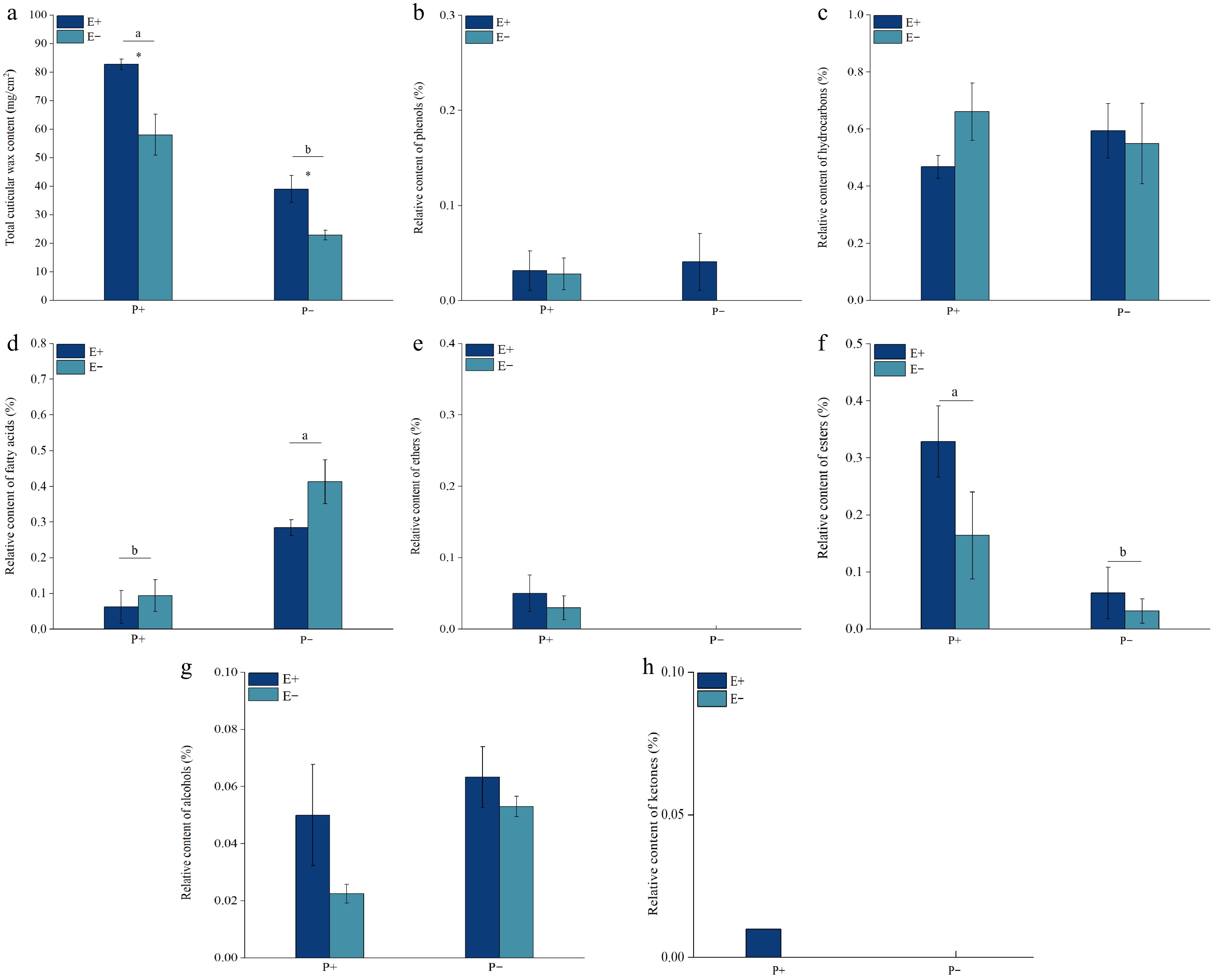

The presence of the Epichloë endophyte had a weaker effect than the B. graminis treatment on the total content of cuticular wax, hydrocarbons, fatty acids, ethers, esters, amines, and alcohols in the leaves of A. inebrians, but the Epichloë endophyte had a stronger effect than B. graminis on cuticular wax phenols in the leaves of A. inebrians (Table 1). Both the Epichloë endophyte and B. graminis (F = 78.062, p < 0.001) had a significant (p < 0.05) effect on the total cuticular wax content in the leaves of A. inebrians, whereas the interaction of the two had no significant effect on the total cuticular wax content in the leaves of A. inebrians (Table 1). The total cuticular wax content of both the E+ and E− plants in the leaves of A. inebrians significantly (p < 0.05) increased when the plants were treated with B. graminis, compared with that of the plants not inoculated with B. graminis. The presence of the Epichloë endophyte significantly (p < 0.05) increased the total cuticular wax content of A. inebrians, with or without B. graminis inoculation (Fig. 2a).

Table 1. Two-way ANOVA analysis the effects of Epichloë endophyte (E), and Blumeria graminis (P) treatments on the total content of cuticular wax, and the relative content of the wax compositions of the leaves of Achnatherum inebrians (n = 5).

Wax composition Treatment df F-value p-value Total content E 1 20.954 0.002 P 1 78.062 < 0.001 E × P 1 0.919 0.532 Phenols E 1 2.855 0.130 P 1 1.608 0.240 E × P 1 0.034 0.859 Hydrocarbons E 1 1.229 0.300 P 1 2.932 0.125 E × P 1 0.880 0.376 Fatty acids E 1 0.013 0.911 P 1 16.539 0.004 E × P 1 0.002 0.966 Ethers E 1 0.186 0.677 P 1 5.800 0.043 E × P 1 0.186 0.677 Esters E 1 4.248 0.073 P 1 15.751 0.004 E × P 1 1.775 0.219 Alcohols E 1 0.901 0.370 P 1 2.254 0.172 E × P 1 0.103 0.757 The values in bold mean significant differences.

Figure 2.

Effects of Epichloë endophyte and B. graminis treatments on the total content of cuticular wax and the relative content of the wax compositions of the leaves of A. inebrians. Values are mean ± standard error (SE), with bars indicating SE. Columns with non-matching letters indicate a significant difference at p < 0.05.

There was no significant (p > 0.05) effect on the content of cuticular wax phenolics in the leaves of A. inebrians when the Epichloë endophyte, B. graminis, or both fungi were present (Table 1). There was no significant (p > 0.05) difference between the cuticular wax phenolic contents of E+ and E− A. inebrians leaves under both the B. graminis and Epichloë endophyte treatments. No cuticular wax phenolics were detected in A. inebrians leaves that were not inoculated with B. graminis (Fig. 2b).

There was no significant (p > 0.05) effect of the presence of the Epichloë endophyte, infection with B. graminis, or the interaction between the two on the cuticular wax hydrocarbons of A. inebrians leaves (Table 1). There was no significant (p > 0.05) difference in the relative content of cuticular wax hydrocarbons in A. inebrians leaves between the B. graminis and Epichloë endophyte treatments (Fig. 2c).

The B. graminis treatment had a significant (p < 0.05) effect on the cuticular wax fatty acids of A. inebrians leaves, whereas neither the presence of the Epichloë endophyte nor the interaction between the two had a significant effect on the cuticular wax fatty acids of A. inebrians leaves (Table 1). The relative cuticular wax fatty acid content of A. inebrians leaves was significantly (p < 0.05) lower under both B. graminis treatments than that of plants not inoculated with B. graminis. There was no significant difference (p > 0.05) in Epichloë endophyte infection with or without B. graminis inoculation (Fig. 2d).

There was no significant (p > 0.05) effect of Epichloë infection, B. graminis infection or the interaction between the two on the cuticular wax ketones of A. inebrians leaves (Table 1). Cuticular wax ethers were detected only in the leaves of A. inebrians treated with B. graminis, and there was no significant (p > 0.05) difference between the cuticular wax ketones of E+ and E− A. inebrians leaves (Fig. 2e).

Treatment with B. graminis had a significant (p < 0.05) effect on the cuticular wax esters of A. inebrians leaves, whereas neither the presence of the Epichloë endophyte nor the interaction of the two had a significant effect on the cuticular wax esters of A. inebrians leaves (Table 1). The relative cuticular wax ester content of A. inebrians leaves was significantly greater (p < 0.05) under both B. graminis treatments than those of plants not inoculated with B. graminis. However, there was no significant difference (p > 0.05) in the presence of the Epichloë endophyte with or without inoculation with B. graminis (Fig. 2f).

There was no significant (p > 0.05) effect of the presence of the Epichloë endophyte B. graminis or the interaction between the two on the cuticular wax alcohols of A. inebrians leaves (Table 1). There was no significant (p > 0.05) difference in the relative content of cuticular wax alcohol in A. inebrians leaves in response to the B. graminis and Epichloë endophyte treatments (Fig. 2g). Cuticular wax ketones were detected only in E+ A. inebrians leaves under B. graminis treatment (Fig. 2h).

Analysis of differentially expressed genes

-

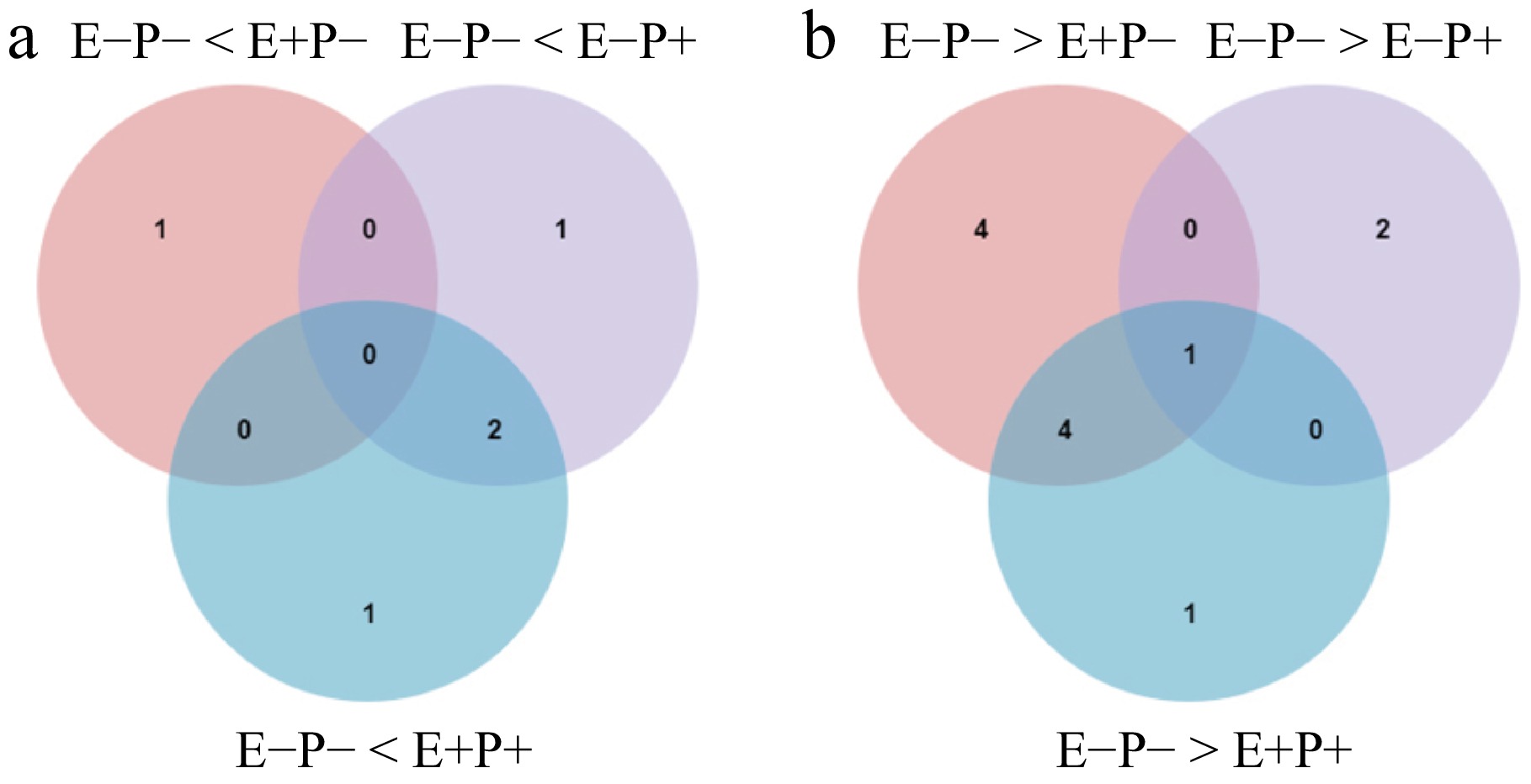

In this study, a total of 15 different genes associated with wax synthesis, and the transport pathway were identified compared with those associated with the E−P− treatment (Supplementary Table S5). Compared with those under E−P−, there were 10 different genes under the E+P− treatment, of which one was upregulated, and nine were downregulated; six different genes under the E−P+ treatment, of which three were upregulated and three were downregulated; and nine different genes under the E+P+ treatment, of which three were upregulated and six were downregulated (Fig. 3a, b).

Figure 3.

Venn diagrams of (a) up-regulated, and (b) down-regulated DEGs of the biosynthesis of leaves cuticular wax in A. inebrians under Epichloë endophyte and B. graminis treatments.

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis

-

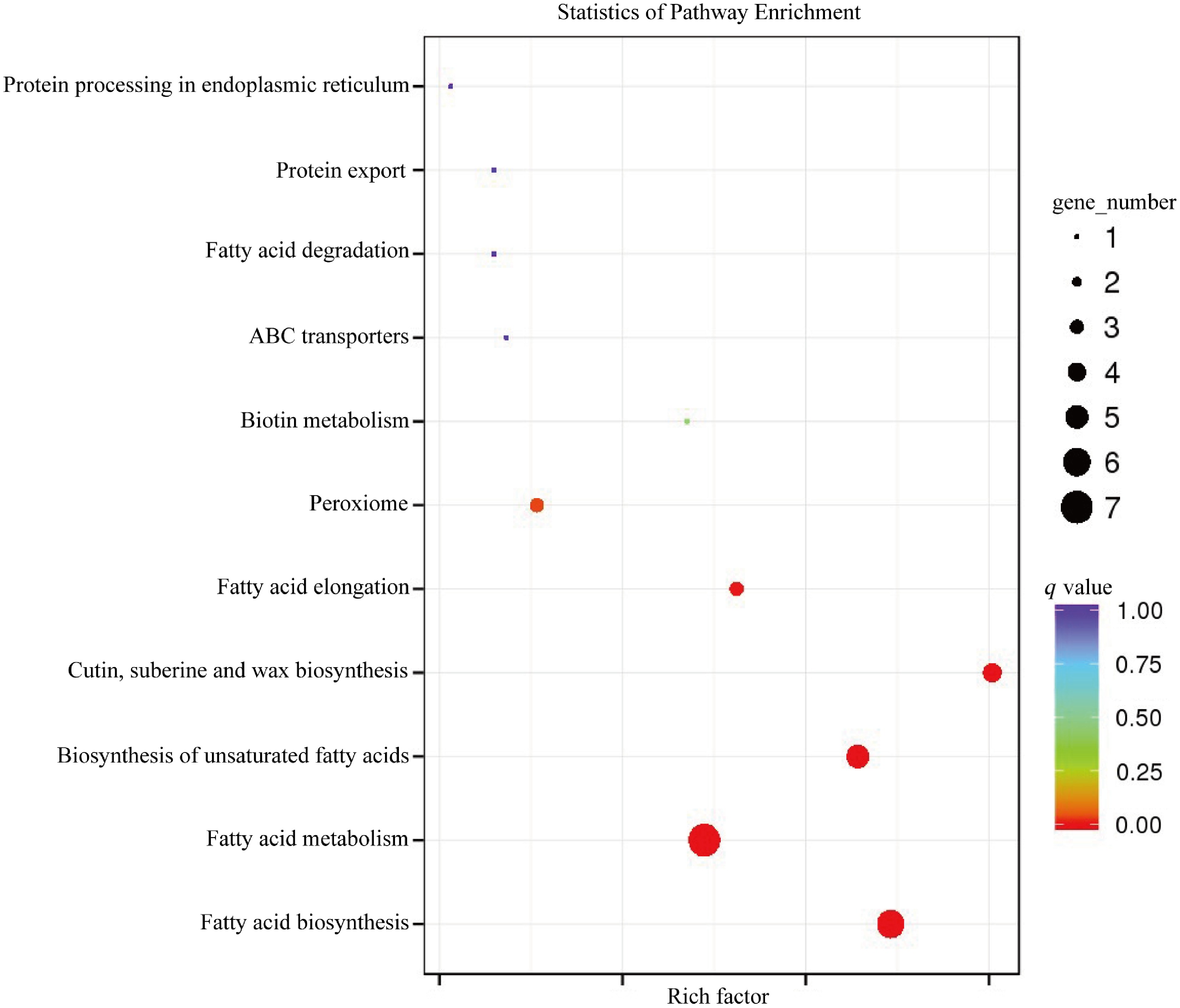

The 15 DEGs detected in this study were enriched in 11 KEGG pathways according to the KEGG pathway enrichment analysis, and were enriched mainly in the fatty acid biosynthesis pathway (ko00061), fatty acid metabolism (ko01212), unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis (ko01040), cutin, suberin and wax biosynthesis (ko00073), fatty acid elongation (ko00062), and peroxisome (ko04146), (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs associated with cuticular wax biosynthesis in A. inebrians leaves in response to Epichloë endophyte and B. graminis treatments.

GO functional annotation and enrichment analysis

-

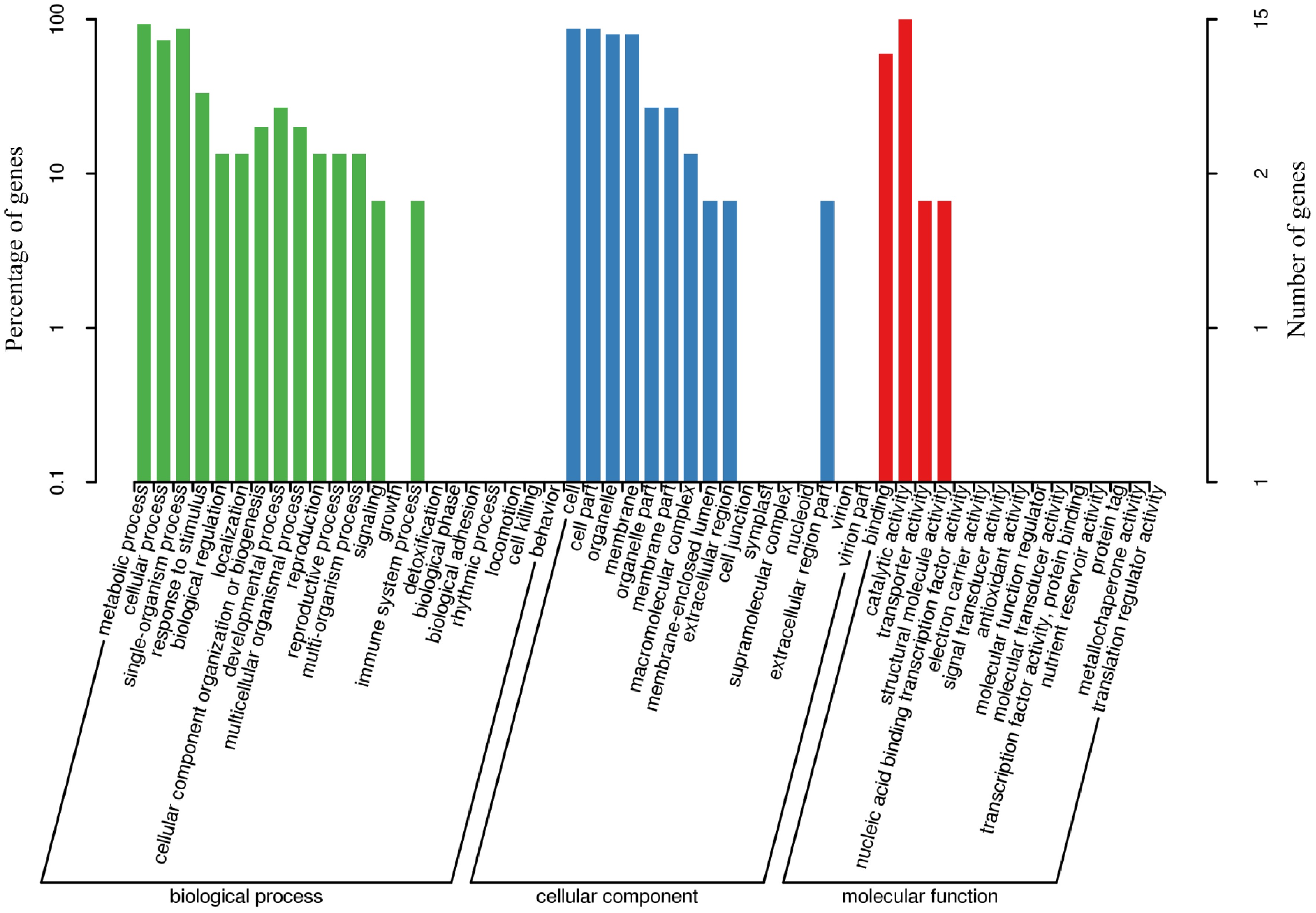

The 15 DEGs were subjected to functional GO annotation, and a total of 28 GO categories were annotated. The annotated sequences were categorized into three main categories: biological process, cellular component, and molecular function (Fig. 5). The biological processes include the metabolic process, single-organism process, cellular process, response to stimulus, developmental process, cellular component organization or biogenesis, multicellular organismal process, biological regulation, localization, reproduction, reproductive process, multi-organism process, signaling, and immune system process. Cellular components include cell, cell part, organelle, membrane, organelle part, membrane part, macromolecular complex, membrane-enclosed lumen, extracellular region, and extracellular region part. Molecular functions include catalytic activity, binding, transporter activity, and structural molecule activity (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

GO functional-enrichment analysis of DEGs associated with the biosynthesis of leaves cuticular wax in A. inebrians under the Epichloë endophyte and B. graminis treatments.

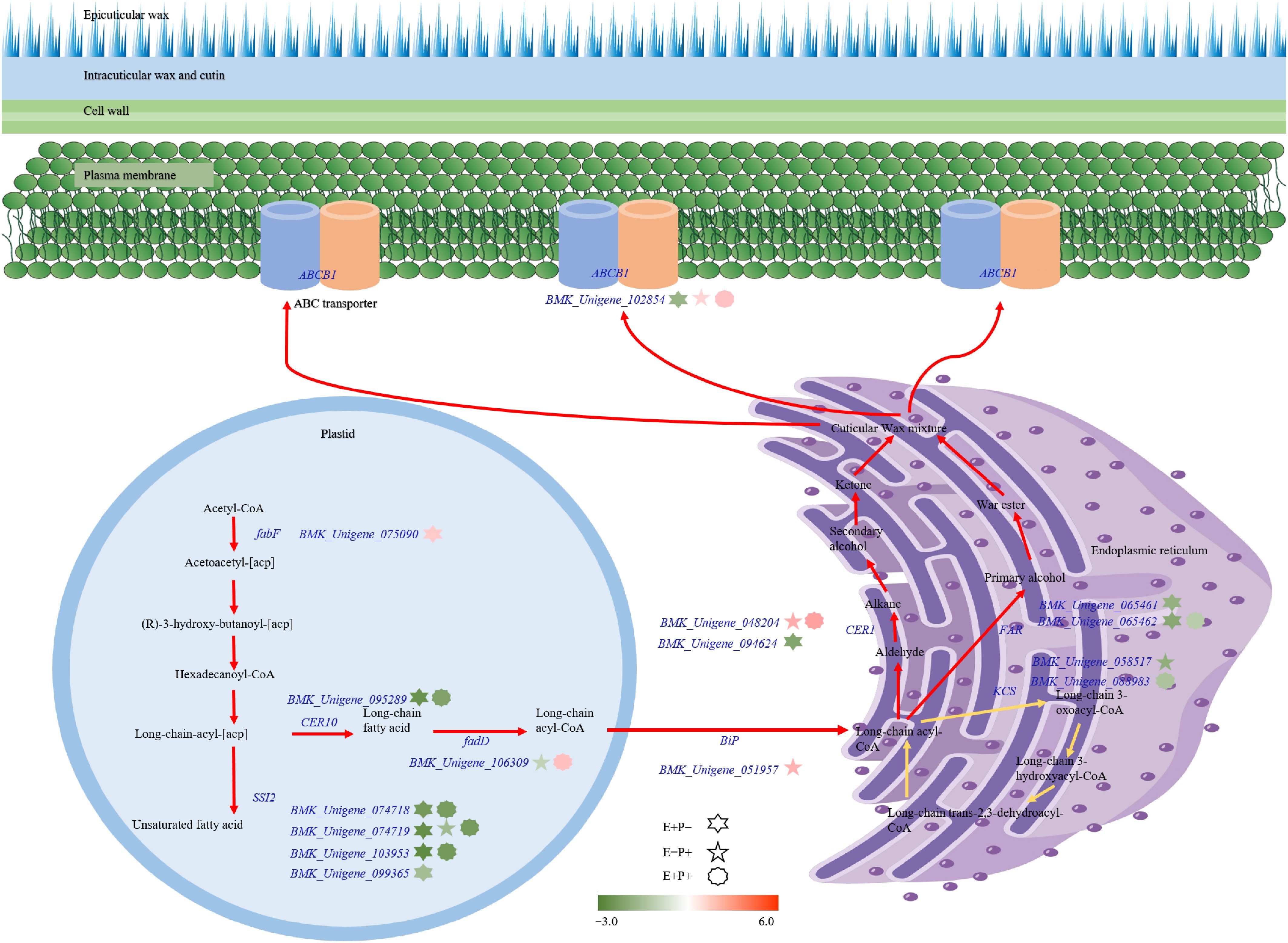

Cuticular wax synthesis pathway

-

The pathway of cuticular wax synthesis in the leaves of A. inebrians can be divided into three main parts: fatty acid synthesis (including fatty acid elongation), wax synthesis, and translocation (Fig. 6). Only the expression of the gene fabF (BMK_Unigene_075090) was significantly (p < 0.05) different between E+P− plants and E−P− plants, whereas FAR (BMK_Unigene_065462, BMK_Unigene_065461), CER1 (BMK_Unigene_094624), ABCB1 (BMK_Unigene_102854), SSI2 (BMK_Unigene_074718, BMK_Unigene_103953, BMK_Unigene_099365, BMK_Unigene_074719), and TER (BMK_Unigene_095289) were significantly (p < 0.05) downregulated. Bip (BMK_Unigene_051957), CER1 (BMK_Unigene_048204) and ABCB1 (BMK_Unigene_102854) were significantly (p < 0.05) expressed in the E−P+ plants, whereas the gene expression of KCS (BMK_Unigene_088983), fadD (BMK_Unigene_106309), and SSI2 (BMK_Unigene_074719) were significantly (p < 0.05) downregulated in the E+P+ plants. fadD (BMK_Unigene_106309), CER1 (BMK_Unigene_048204), and ABCB1 (BMK_Unigene_102854) were significantly (p < 0.05) upregulated, while KCS (BMK_Unigene_058517), FAR (BMK_Unigene_065462), SSI2 (BMK_Unigene_074718, BMK_Unigene_103953, BMK_Unigene_074719), and TER (BMK_Unigene_095289) were significantly (p < 0.05) downregulated (Fig. 6).

-

In this experiment, GC-MS and transcriptome sequencing analyses revealed that the major components of cuticular waxes in A. inebrians leaves were hydrocarbons, esters, and fatty acids. Moreover, B. graminis infection significantly increased the total cuticular wax and ester contents in both E+ and E− A. inebrians leaves, with the total wax content being significantly higher in E+ plants than in E− plants. Transcriptome analysis revealed that the expression of 15 genes involved in wax biosynthesis and transport was differentially regulated under the combined influence of B. graminis infection and Epichloë endophyte association.

Effect of pathogen stress and Epichloë endophyte on the wax content and composition of plant leaf cuticular wax

-

In the present study, the total cuticular wax content in the leaves of A. inebrians significantly increased under B. graminis treatment, and the total cuticular wax content in the leaves of E+ A. inebrians was significantly greater than that in the leaves of E− A. inebrians, which was consistent with the results of studies by Kou[27] and Zhao[28]. In addition, this study indicates that the relative content of fatty acids significantly decreased under B. graminis treatment, consistent with the findings of Wang et al.[29]. GC-MS analysis revealed that the main constituents of the cuticular wax of A. inebrians leaves treated with the Epichloë endophyte and B. graminis were hydrocarbons, esters, and fatty acids, with hydrocarbons being the most abundant. The main component of the cuticular wax of A. inebrians leaves under the Epichloë endophyte and various moisture treatments by Zhao[28] and Kou[27] was hydrocarbons. Bourdenx et al.[30] noted that the cuticle matrix and cuticle waxes constitute the cuticle, which is mainly composed of very long-chain (VLC) hydrocarbons, and that hydrocarbons account for 70% of the total wax content in Ar. thaliana leaves. Pascal et al.[31] also demonstrated that of all wax fractions, hydrocarbons account for 80% of the total cuticular wax content in Ar. thaliana leaves. However, the main components of leaf cuticular wax in rice and maize are primary alcohols, aldehydes, fatty acids, and hydrocarbons account for less than 15% of the total wax[32,33]. The composition of biosynthesized wax can vary considerably depending on species, individual development, and environmental growth conditions[21], and the wax content often varies even within the same species and organ[20].

Effects of pathogen stress and Epichloë endophyte on plant leaf cuticular wax synthesis and transporter genes

-

Increasing evidence suggests that the structure and composition of epidermal waxes may change following fungal and pathogenic infections[18,29]. For example, following gray mold infection in grapes, genes associated with wax synthesis and transport were either up- or down-regulated, while differential transcription factors (TFs) also exhibited significant expression changes[29]. Powdery mildew caused by B. graminis can utilize wax components in plant epidermis to initiate critical early life cycle stages, including conidia germination and spore attachment[34,35]. Research has shown that knocking out the key enzyme 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase (TaKCS6) significantly reduces wax accumulation, thereby inhibiting the germination of B. graminis[36]. Similarly, studies by Kong & Chang[37] and Wang et al.[36] demonstrated that silencing TaKCS6 and acyl-CoA reductase (TaECR), also weakened powdery mildew spore germination.

Research in Arabidopsis has identified numerous genes encoding wax biosynthetic enzymes, which are also applicable to other plants. Consequently, knowledge of wax biosynthesis, translocation, and regulation in Arabidopsis can be leveraged to identify homologous genes in various crop species and develop cold-tolerant varieties[20]. Wax biosynthesis begins with the synthesis of C16 or C18 fatty acids in epidermal plastids. These long-chain fatty acid compounds are converted into coenzyme A thioesters by isoenzymes of long-chain acyl-CoA synthase (LACS) and ultimately transferred to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)[38]. In this study, it was found that the endophytic fungus Epichloë significantly upregulated the expression of the fadD gene (BMK_Unigene_106309), encoding the LACS enzyme, following treatment with B. graminis. Additionally, the expression of the endoplasmic reticulum chaperone-binding protein (BiP) was also upregulated under B. graminis stress, consistent with the findings of Zhu et al.[39].

Cuticle wax serves as the primary interface in plant-pathogen interactions; higher wax coverage forms a thicker lipid barrier, thereby delaying cuticle degradation[29]. CER1 (BMK_Unigene_048204), a gene associated with cuticle and wax synthesis, was found to be upregulated and expressed in the cuticular wax of both E+ and E− A. inebrians under B. graminis stress. The ECERIFERUM1 (CER1) gene in Arabidopsis controls alkane biosynthesis and is closely associated with various stress responses[30]. In Arabidopsis CER4 mutants, the content of primary alcohols and wax esters in stems is significantly reduced, while the content of aldehydes, hydrocarbons, secondary alcohols, and ketones are slightly increased. In epidermal and root tissues of above-ground organs, fatty acyl-CoA reductase 3 (FAR3/CER4) likely catalyzes the reduction of VLC acyl-CoA to tertiary alcohols via unreleased aldehyde intermediates[40]. However, in this study, it was found that two FAR genes (BMK_Unigene_065462, BMK_Unigene_065461) in the cuticular wax of A. inebrians leaves were downregulated upon treatment with Epichloë endophytes. Furthermore, the presence of Epichloë endophytes altered the differential expression of the CER10 gene (BMK_Unigene_095289) in the cuticular wax of A. inebrians leaves. Following synthesis, wax, and keratin precursors are transported out of the endoplasmic reticulum, traverse the plasma membrane, and reach the developing cuticle membrane. This process relies on ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters. ABCG11/WBC11 is a key component of the epidermal lipid export pathway in Arabidopsis, and may interact with CER5 in surface wax secretion[41]. B. graminis treatment upregulated the expression of ABCB1 subfamily genes in A. inebrians leaves, whereas Epichloë endophytes suppressed expression of ABCA1 subfamily genes in uninoculated B. graminis-treated A. inebrians leaves, consistent with findings by Kou[27] and Zhao et al.[26].

-

In conclusion, this study highlights the regulatory roles of pathogen stress and the Epichloë endophyte in the synthesis and transport of cuticular waxes in A. inebrians leaves, thereby influencing wax composition. These findings enrich our understanding of how endophyte-host interactions modulate cuticular wax metabolism at both molecular and compositional levels during pathogen infection. Although the present study reveals clear molecular and compositional changes in wax metabolism, further functional verification is needed to clarify how these changes contribute to enhanced disease resistance. Future research should focus on experimentally validating the roles of key wax-related genes, and elucidating how endophytic fungi regulate wax biosynthetic pathways under different environmental conditions. This work provides a valuable theoretical foundation and new perspectives for improving crop disease resistance and environmental adaptability through targeted regulation of wax metabolism.

This research was funded by the Gansu Provincial Science and Technology Major Projects (23ZDNA009), the National Nature Science Foundation of China (32061123004), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (lzujbky-2022-ey21), Lanzhou University. We would like to thank the editor and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and experimental design: Zhu Y, Zhang X; data collection: Zhu Y, Cao K; statistical analysis, manuscript preparation: Zhu Y; draft manuscript preparation: Zhu Y, Christensen JM, Zhang X. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary materials (published online). The RNA-seq used in this study has been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) of the NCBI database under the Accession No. PRJNA748183.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Tables S1 Qualitative GC-MS analysis of the leaf extract of Epichloë endophyte- infected Achnatherum inebrians under pathogen-inoculated (P+), elucidation of empirical formulas and putative identification (where possible) of the compounds.

- Supplementary Table S2 Qualitative GC-MS analysis of the leaf extract of Epichloë endophyte-free A. inebrians under pathogen-inoculated (P+), elucidation of empirical formulas and putative identification (where possible) of the compounds.

- Supplementary Table S3 Qualitative GC-MS analysis of the leaf extract of Epichloë endophyte-free A. inebrians under non-inoculated (P-), elucidation of empirical formulas and putative identification (where possible) of the compounds.

- Supplementary Table S4 Qualitative GC-MS analysis of the leaf extract of Epichloë endophyte-infected A. inebrians under non-inoculated (P-), elucidation of empirical formulas and putative identification (where possible) of the compounds.

- Supplementary Table S5 Selected genes associated with cuticular wax biosynthesis in A.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu Y, Cao K, Christensen MJ, Zhang X. 2026. Cuticular wax modification by Epichloë endophyte in Achnatherum inebrians under Blumeria graminis infection. Grass Research 6: e002 doi: 10.48130/grares-0025-0030

Cuticular wax modification by Epichloë endophyte in Achnatherum inebrians under Blumeria graminis infection

- Received: 03 July 2025

- Revised: 15 October 2025

- Accepted: 20 October 2025

- Published online: 21 January 2026

Abstract: Achnatherum inebrians is a perennial plant belonging to the Poaceae, subfamily Pooideae, which often forms a symbiosis with fungal endophytes of the genus Epichloë. In this study, E. gansuensis-infected (E+) and E. gansuensis-free (E−) A. inebrians were inoculated with Blumeria graminis (pathogen-inoculated, P+; non-inoculated, P−) under greenhouse conditions. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and transcriptome sequencing were combined to characterize the response of the leaf cuticular wax of A. inebrians plants with and without the Epichloë endophyte to B. graminis stress. The present results revealed that the predominant components of the cuticular wax of A. inebrians leaves under the Epichloë endophyte and B. graminis treatments were hydrocarbons, esters, and fatty acids. The total cuticular wax and ester contents of the E+ and E− A. inebrians leaves significantly (p < 0.05) increased under the B. graminis treatment, but the total cuticular wax and ester contents of the E+ leaves were greater than those of the E− plants. Through transcriptome analysis, 15 genes that were differentially expressed and related to cuticular wax biosynthesis were identified, including fadD, fadF, TER, SSI2, BiP, CER1, FAR, and KCS.