-

Biochar is a recalcitrant, carbon-rich material that rapidly modifies the chemical, physical, and biological fabric of soil. Because biochar simultaneously improves soil quality, reduces contamination, and boosts yield, biochar amendment is increasingly viewed as a 'win–win' technology for ecosystem service delivery[1]. Although the particles themselves are barely biodegradable, they exude labile, microbially accessible compounds into the surrounding few millimeters of soil, creating a functional micro-territory, called 'charosphere' that is analogous to the rhizosphere[2,3]. Within this 1–2 mm envelope, steep gradients in pH, dissolved organic carbon (DOC), and redox potential emerge within hours, and the resulting pore water chemistry diverges sharply from that of the bulk soil[4].

Fresh biochar establishes an alkaline halo that can extend 1.13–1.63 mm from the particle surface within 24 h, but aging contracts the reactive zone to 1.08–1.12 mm. Despite the pivotal role in post-application biogeochemistry, the temporal evolution of the charosphere, particularly the persistence and magnitude of its pH signature, remains poorly resolved. What is clear is that even this narrowed micro-interface continues to govern heavy-metal behavior. Elevated pH and abundant surface ligands enhance Cd adsorption, lower its bioavailability, and thereby alleviate metal stress on the soil microbiome[5].

Correlation and redundancy analyses were used to link biochar properties to the characteristics of the charosphere they create. Irrespective of age, however, the radius of the charosphere is the master variable that governs local soil chemistry. Within hours of application, steep gradients develop, extending 1.08–1.63 mm from the biochar surface[6]. Across this narrow band, DOC, available phosphorus, and exchangeable Ca2+, Mg2+, and K+ all increase toward the particle, while pH and labile carbon decline with distance[7]. Mapping the spatial arrangement of these functional variables within the charosphere thus provides a geometric framework for predicting how biochar amendments modify soil fertility and nutrient delivery in agroecosystems[8].

Within the charosphere, biochar acts as a high-affinity sorbent that rapidly deactivates Cd. By raising pH and lowering both acidity and soluble metal pools, the amendment alleviates environmental stress and sharply differentiates the charosphere from unamended bulk soil[5]. Wang et al.[9] reported a 25%–40% drop in the acid-soluble Cd fraction inside this micro-zone and a concomitant increase in the residual fraction, confirming that Cd is transferred from the soil solution onto the biochar surface and thereby stabilized. Therefore, plant roots encounter a depleted Cd pool. The majority of the once-bioavailable Cd is immobilized in the rhizosphere-adjacent soil or on root surfaces, and only a minor fraction reaches aboveground tissues[10]. Beyond sorption, charosphere biochar can activate -OH radicals, catalyze heavy metal redox reactions, and retain its reactivity over multiple cycles, ensuring both durable immobilization and even spatial distribution of the ameliorant[11].

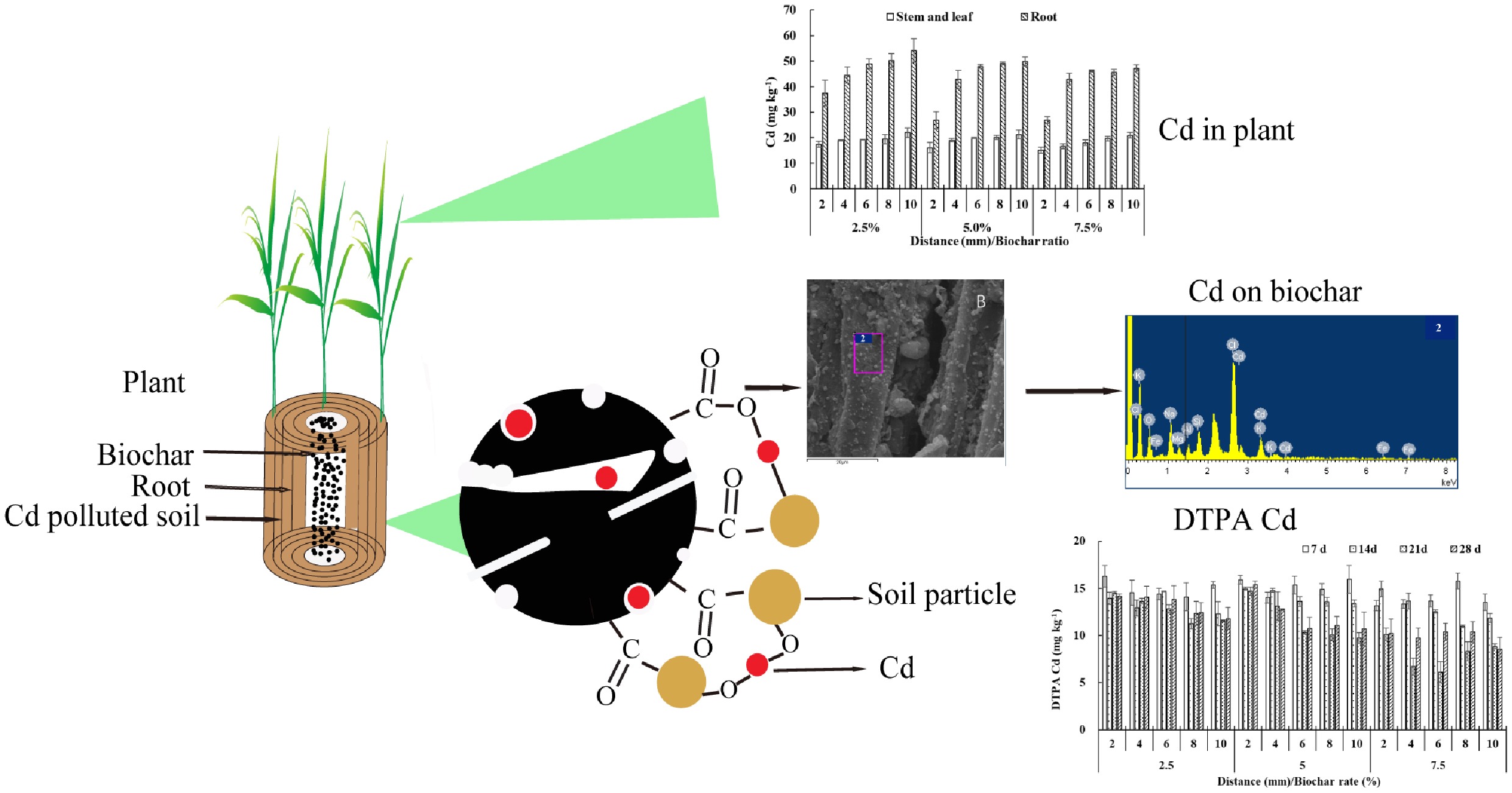

It is therefore hypothesized that the combined effects of elevated pH, DOC, and surface functional groups within the charosphere suppress Cd solubility and plant uptake. Using a stratified microcosm with controlled biochar placement, the study provides the first mechanistic evidence that Cd immobilization is governed by steep microscale gradients extending 0–10 mm from the particle surface.

-

Wheat straw was obtained from local farmers, air-dried, and chopped into small pieces before being oven-dried at 105 °C. The dried material was pyrolyzed at 450 °C (the selected pyrolysis temperature was based on the company's scale production) for 4 h in a vacuum tube furnace (NBD-O1200, Nobody Materials Science and Technology Co., Ltd, Zhengzhou, China) under a nitrogen flow of 500 mL min−1, with a heating rate of 10 °C min−1. After cooling, the resulting biochar was ground and passed through a 0.15 mm sieve. Basic physicochemical properties of the biochar were analyzed following the methods described by Lu[12] and are presented in Supplementary Table S1. The charosphere soil sample was treated with the method of lab culture. The soil sample was ground fine and screened to 10 mesh. Eighty grams of contaminated soil was used, and the biochar was placed around the column at rates of 2.5%, 5% and 7.5% (w/w). Soil was wrapped around the biochar column in concentric layers separated by 400-mesh nylon cloth, each layer being approximately 2 mm thick (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Five uniform wheat seeds were surface-sterilized in 1% NaClO for 15 min, thoroughly rinsed with distilled water, and soaked in clean water for 24 h. Five seeds (which had sprouted a small radicle in the incubator) were sown in each layer (five layers for each treatment) of the top and incubated at 50% relative humidity and a 12-h photoperiod (06:00–18:00). Each treatment was replicated three times, and samples were collected after the specified incubation period.

Four weeks after sowing, wheat was harvested. Shoots and roots were rinsed three times with tap water, followed by three washes with deionized water. Plant material from each sampling ring was placed in paper envelopes, oven-killed at 105 °C for 30 min, and then dried to constant weight at 60 °C. The dried tissues were ground, homogenized, and stored in polyethylene bags until analysis; Cd and Pb concentrations were determined as described in the Supplementary File 1. Soil was sampled at 7, 14, 21, and 28 d from concentric zones located 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 mm from the biochar layer. Samples were air-dried and passed through a 2 mm sieve prior to analysis. Soil pH was measured in a soil:water (1:2.5, w:v) suspension using a pH meter (pHS-3B, Shanghai, China). DOC was extracted at a soil:water (1:3, w:v) ratio by shaking for 1 h at 250 rpm, centrifuging at 12,000 g for 10 min, filtering through pre-washed Whatman paper, and analyzing the filtrate with a Multi N/C 2100 analyzer (Analytik Jena, Germany). The soil available Cd was determined by extracting 5.00 g of soil with 10 mL of 0.005 M DTPA (pH 7.3) for 2 h at 180 rpm. After centrifugation, the supernatant was filtered (0.45 µm), and Cd in the filtrate was quantified by flame atomic-absorption spectrophotometry (AAS, TAS-986, Persee, China). A certified reference material of sediment GBW 07406 (0.13 ± 0.04 mg kg−1 Cd) from the National Centre for Certificate Reference Materials, China, was used as an internal standard in each batch of digestions, and the Cd recovery was between 85% and 120%.

Statistical analysis

-

The data are reported as means ± one standard deviation. Treatment effects were first evaluated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) at α = 0.05, and then pairwise comparisons of means were performed with Tukey's honestly significant difference test. Computations were executed in SPSS v. 22.0 (SPSS Inc., USA). For principal component analysis (PCA), the raw data matrix was z-score normalized, the Pearson correlation matrix was computed, and the resulting eigenvectors were extracted by orthogonal rotation within SPSS to identify the dominant relationships among the measured variables.

-

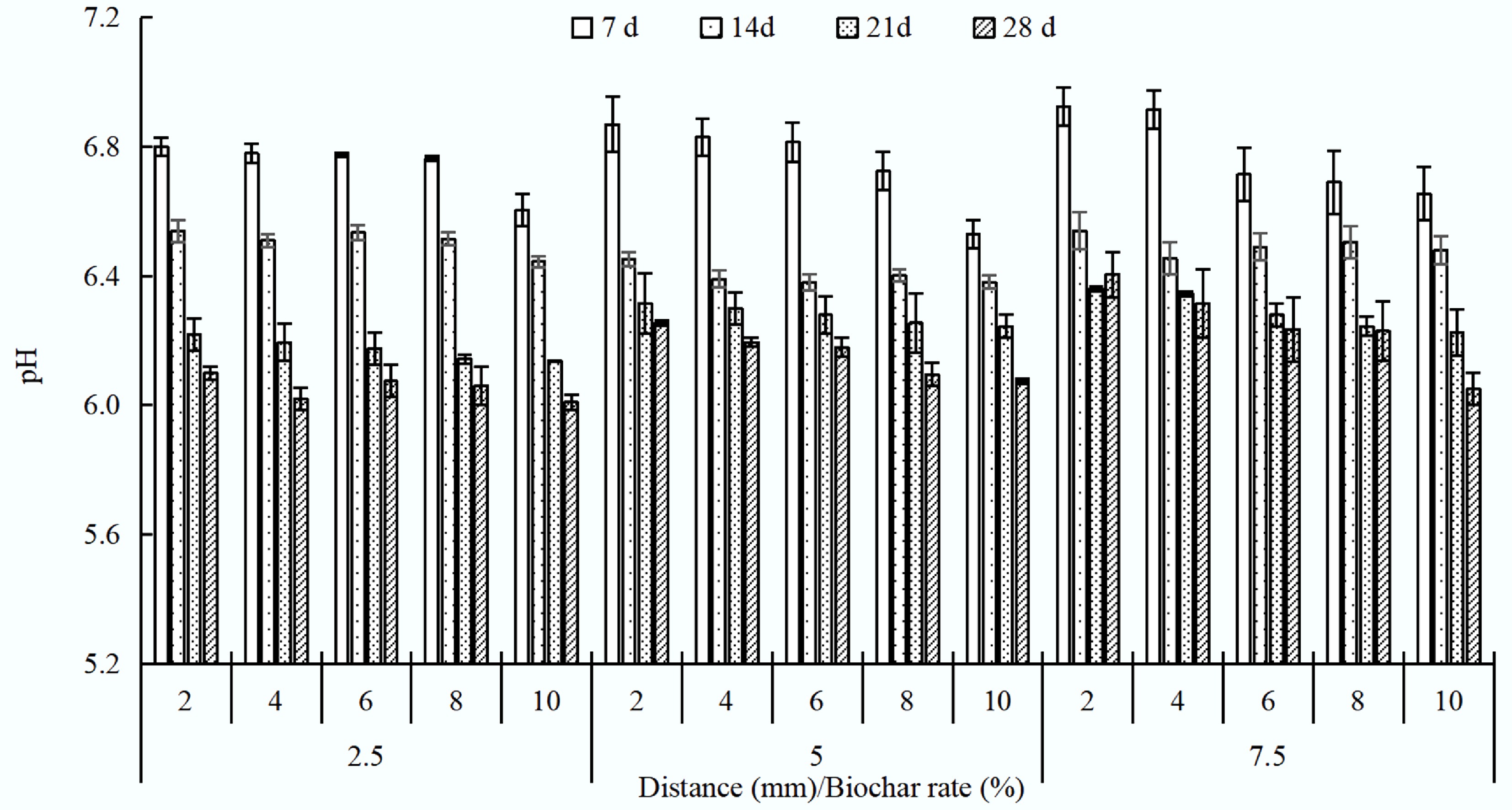

All biochar treatments increased soil pH in the charosphere compared with the non-charosphere (10 mm), with larger increases at higher application rates (Fig. 1). The pH increased by 0.02–0.20 (2.5% biochar), 0.01–0.34 (5% biochar), and 0.01–0.36 (7.5% biochar) units in the charosphere during 28 d. Biochar effects extended to 10 mm in heavy metals-polluted soil, and higher application rates provided more alkaline ions, which were the primary reason for the pH increase. The pH decreased with increasing distance from the charosphere and decreased by 0.02–0.20 (2.5% biochar), 0.16–0.76 (5% biochar), and 0.18–0.60 (7.5% biochar) units over a longer cultivating period during 28 d. The 3% biochar treatment also raised soil pH and thereby reduced heavy-metal mobility[13]. Wang et al.[9] also reported that the pH of all biochars declined by the end of the experiment, followed by a secondary slow decrease. Meng et al.[5] also observed that charosphere soil pH increased after application of swine-manure-derived biochar to Cd-polluted soil.

Availability of Cd in soil

-

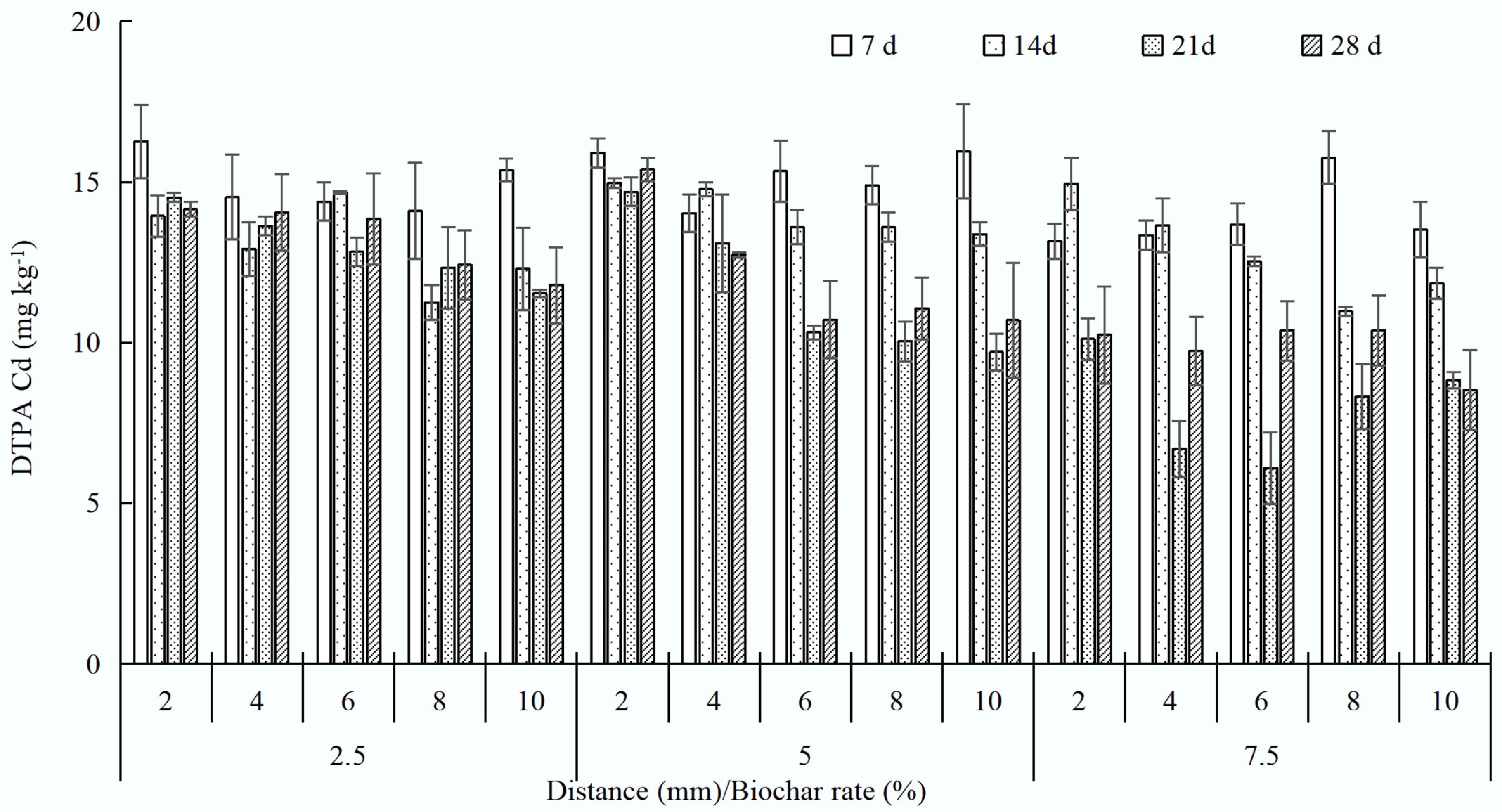

Biochar reduced bioavailable Cd concentrations in the 2-mm charosphere by 10.7%–14.2% (2.5%), 3.2%–7.6% (5%), and 0%–7.6% (7.5%) over 28 d (Fig. 2). The effects of biochar on the immobilization of Cd in soil were indicated by monitoring the concentrations of DTPA-extractable Cd. Compared with the control (CK), the DTPA-extractable Cd in the charosphere soil decreased significantly and then remained stable during the 28 d. In the first 7 d, biochar clearly reduced the DTPA-extractable Cd in the charosphere soil. Then the concentrations rose to steady values of approximately 0.7, 0.8, and 0.11 mg kg−1, respectively, with swine manure biochar at pyrolysis temperatures of 300, 500, and 700 °C. In another experiment, the levels of DTPA-extractable Cd in biochar were decreased by 37.5%, relative to the CK[9]. The unstable Cd species (acid-soluble and reducible fractions of Cd) also decreased with successive cultivation, increasing the biochar ratio in the soil[14].

Cd concentration decreased from the charosphere to the non-charosphere zones, mainly attributed to interactions among aging biochar, soil, and Cd. Mehrab et al.[15] also proved that the DTPA-extractable Cd was 65%–75% lower with biochar application than in the control. Application of biochar also decreased exchangeable (5-fold), carbonate (1.3-fold), and oxidizable (1.6-fold) fractions of Cd but increased reducible (1.3-fold) and residual (1.7-fold) fractions of Cd compared to the control. Treatment with biochar reduced soil HAc-Cd, CaCl2-Cd, and DTPA-Cd concentrations by 8.7%–25.2%, 16.4%–24.5%, and 10.7%–15.8% compared with the control, respectively, and significantly decreased mycelium Cd absorption[16].

Changes in DOC

-

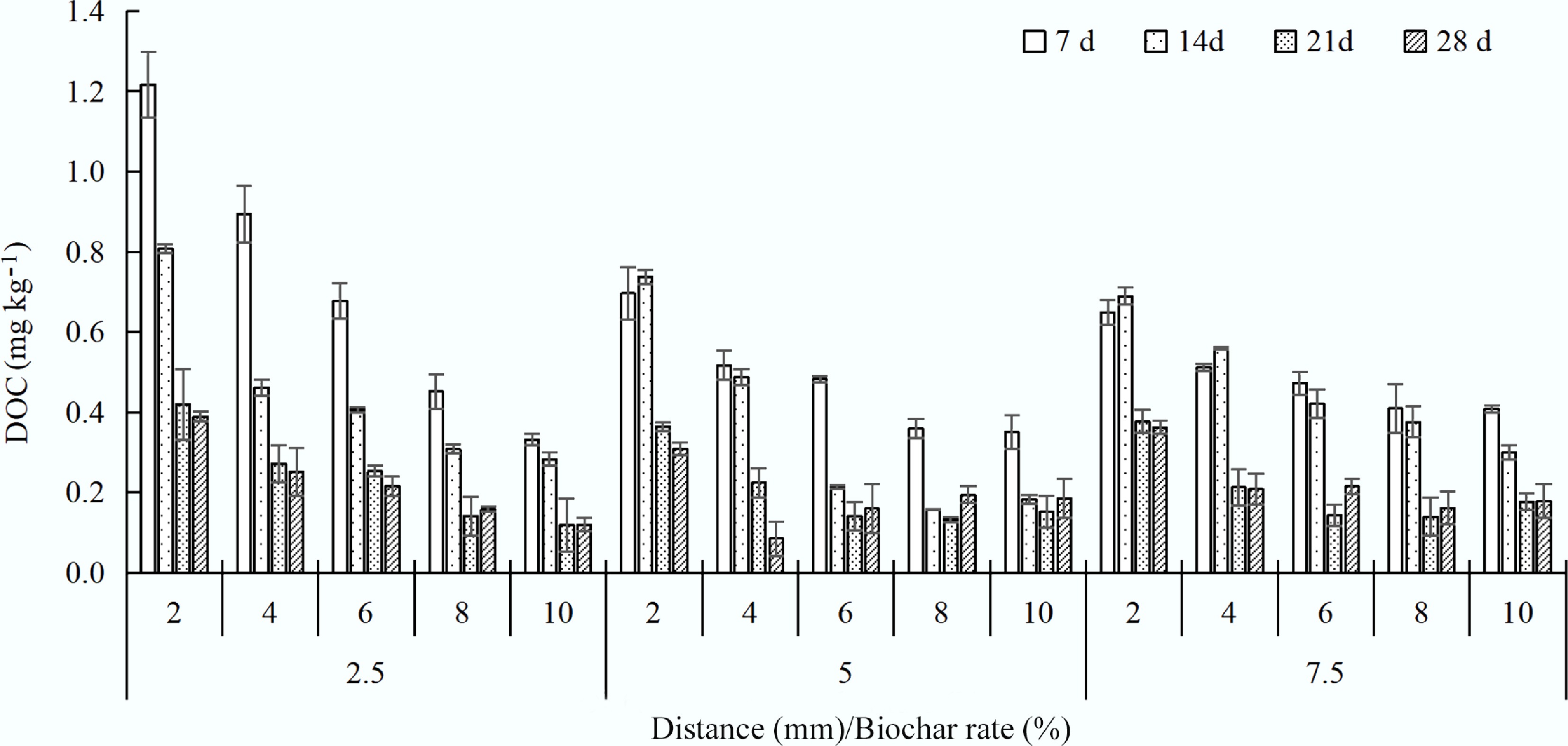

Dissolved organic carbon (DOC) is considered the most mobile fraction of organic matter, consisting of organic components of varying molecular weights from biochar, which was correlated with the solubility of heavy metals in soil[17]. DOC concentration decreased with increasing distance from charosphere in solution, which also decreased over time compared with 7 d (Fig. 3). The increased DOC was mainly from the charosphere, which was greatly decreased by 14.7%–72.5% (7 d), 16.0%–71.7% (14 d), 33.4%–71.5% (21 d), and 31.8%-69.1% (28 d) from 2 to 10 mm. Easily degradable DOC was likely consumed by microorganisms or naturally degraded, with over 50% degradation in 28 d compared to 7 d. DOC was also related to biochar type; the soil DOC contents of peanut shell biochar and rice husk biochar in all the treatments were significantly increased by 11%–27% and 7%–36%, respectively, compared with the control treatment[18]. The corn straw-derived biochar also increased DOC by 197.50% at 90 d in peatland soil[19]. Xue et al.[2] also found that the contents of total carbon (TC) increased by 6.36% compared with the control. The humic-like substances in BC-derived DOC affected the composition of soil DOC and effectively reduced Cd bioavailability[20].

Cd concentration in wheat distribution

-

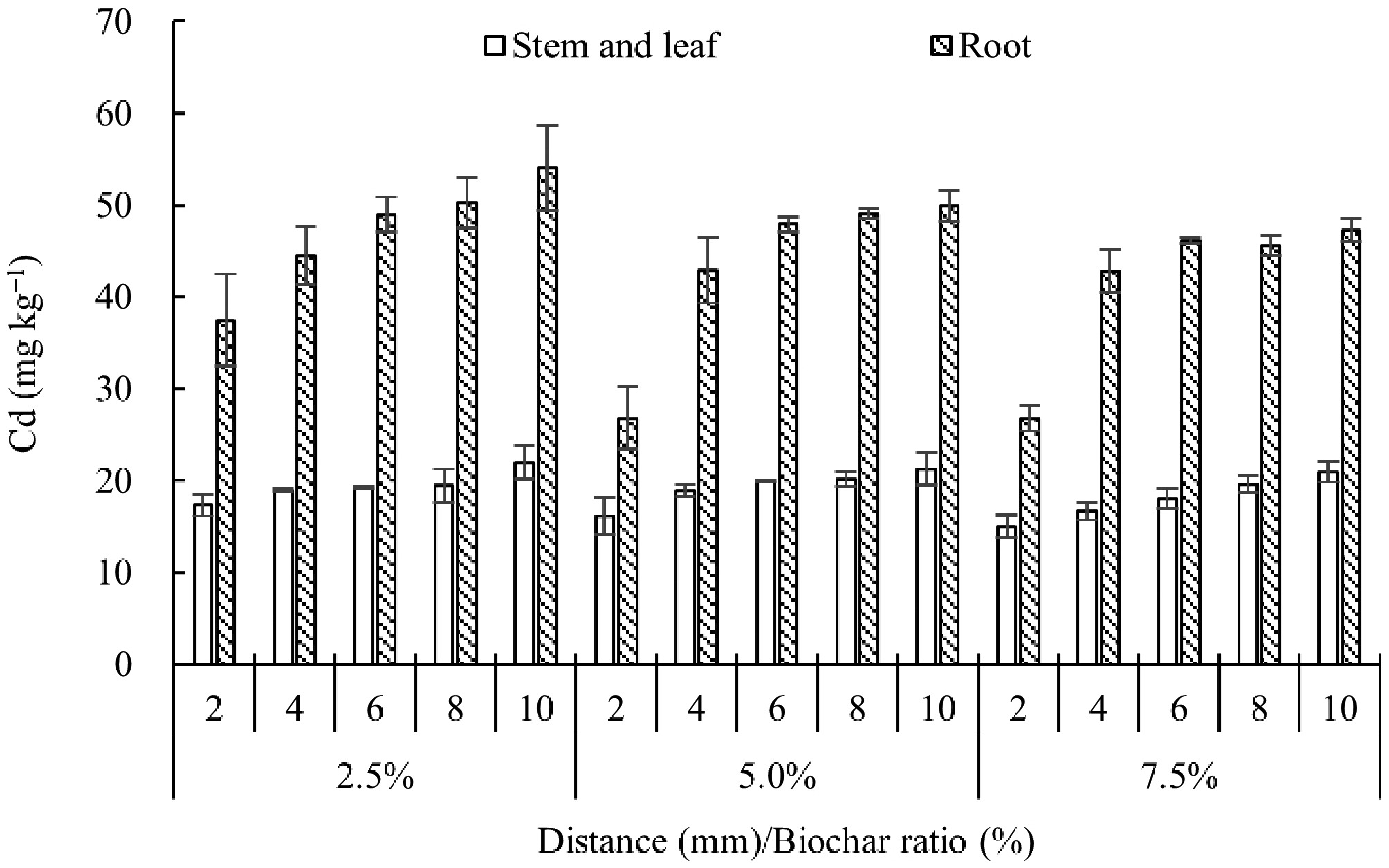

Figure 4 shows the Cd concentration gradient in wheat shoots and roots. Both tissues exhibited a clear decline in Cd with increasing biochar application rate and distance from the charosphere. Relative to the 10 mm position, shoot Cd reduced by 5.3%–28.3% and root Cd by 2.3%–46.3% across the 2–8 mm zone. At 2 mm from the charosphere, 5% and 7.5% biochar lowered shoot Cd by 7.1%–28.5% and root Cd by 28.5%–31.2%. This protective effect weakened progressively with distance, confirming that biochar immobilization operates over a few millimeters. Consistent with the data, Li et al.[21] reported that increasing biochar from 0% to 3% decreased the Cd bio-accumulation factor from 5.84 to 3.80. The reduced upward translocation of Cd is ascribed to (1) enhanced soil fixation (42.8%–59.5% of total Cd converted to residual phases) and (2) the electron-donating capacity of biochar that limits Cd solubility[22]. Consequently, shoot Cd accumulation in wheat dropped by 42%–47% after biochar amendment, a response linked to a higher soil pH (8.6–9.6) and a 30%–45% decrease in CaCl2-extractable Cd in the 0–20 cm layer[23].

Characteristics of biochar

-

The SEM-EDS analysis revealed that the biochar surfaces were only mildly corroded after soil exposure and exhibited elevated C and O signals, confirming the persistence of oxygen-rich functional groups (Supplementary Fig. S2). EDS maps show co-localized Cd, Fe, and Si within the charosphere system, suggesting that Cd is sequestered through direct interaction with biochar-bound elements[24]. Successful metal loading is attributed to the formation of surface complexes between Cd and carboxyl, hydroxyl, and quinone moieties[25]. The Cd adsorption capacity of urban green waste biochar positively correlates with O/C and (O + N)/C ratios[21].

Further analysis of C and O was conducted by XPS of biochar and is shown in Supplementary Fig. S3. The C1s envelope was dominated by graphitic C–C (284.7 eV), with subordinate C–O (285.5 eV), C=O (286.8 eV), and C–N (287.3 eV) contributions, whereas the O1s region exhibited peaks for quinone/carbonyl C=O (531.1 and 532.8 eV) and C–O (533.5 eV). Sorption of Cd and Pb partially oxidized the carbon skeleton, decreasing the relative abundance of C=C/C–C at 284.8 eV and increasing functionality of C–O at 286.2 eV[26,27]. Fourier-transform infrared spectra (Supplementary Fig. S4) reveal the abundance of oxygen-containing groups such as a broad –OH stretch at 3,423 cm−1, aromatic C=C at 1,600 cm−1, C–O–C asymmetrical stretch at 1,094 cm−1, carboxyl C=O at 1,034 cm−1, aromatic C–H out-of-plane bending at 797 cm−1, and Si–O–Si symmetrical stretch at 538 cm−1[28]. These moieties act as Lewis-base ligands that co-precipitate or chelate Cd2+ and Pb2+, while the condensed, graphene-like C=C matrix indicates long-term stability against microbial decay[29−31]. Thus, the multi-functional surface chemistry of biochar, rich in Si–O, Fe–O, –OH, C–O, and –COOH groups, provides both immediate metal-binding capacity and enduring immobilization within the soil profile[32].

Relationship of the characteristics of charosphere and soil

-

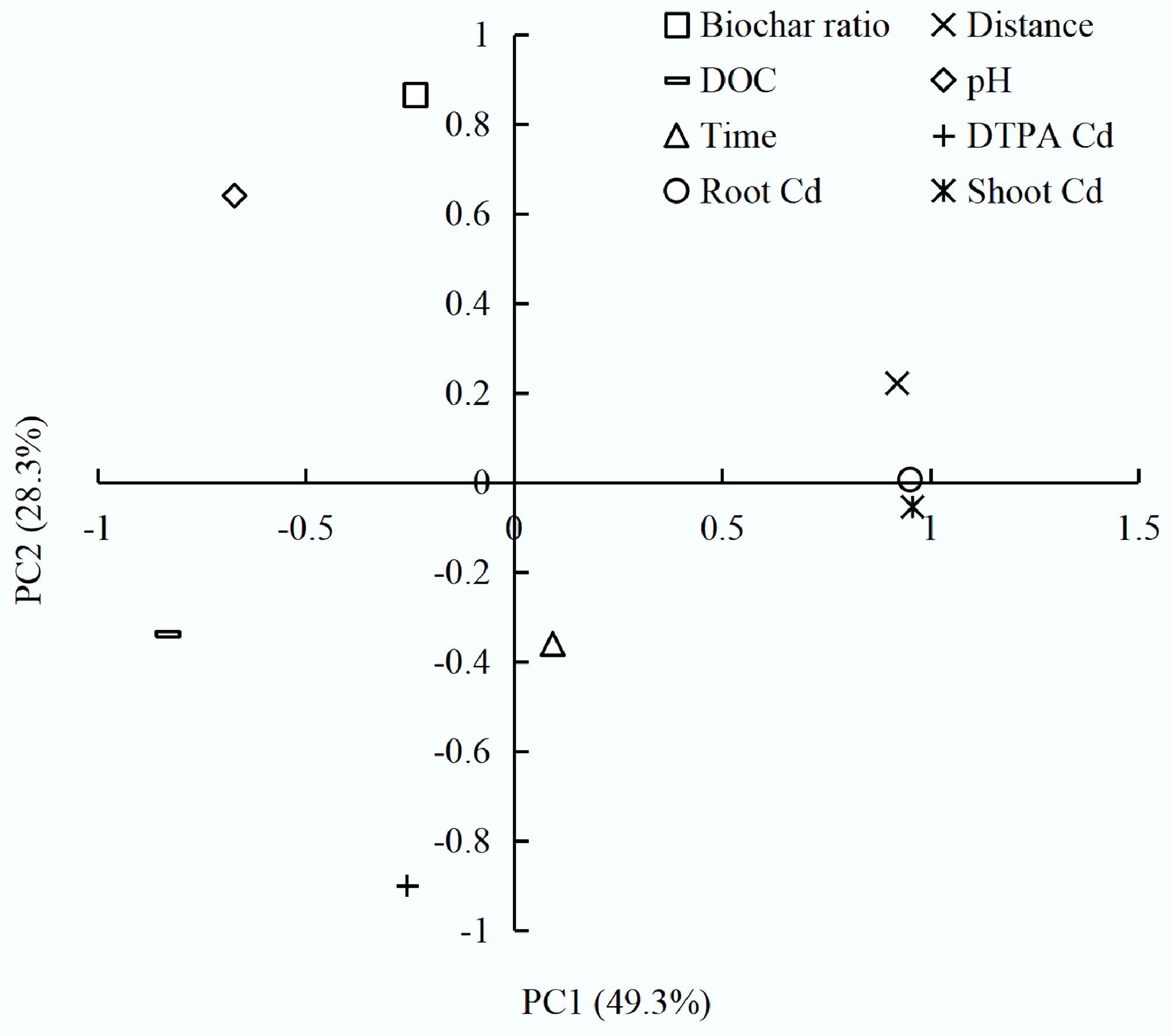

PCA was used to investigate the interactive effects of biochar amendment within the charosphere on Cd bioavailability and soil properties (Fig. 5). Seven key variables, such as biochar rate, pH, distance from the charosphere, elapsed time, dissolved organic carbon (DOC), DTPA-extractable Cd, and Cd concentrations in wheat roots and shoots, were log-transformed and standardized before extraction of three orthogonal components that collectively explained 91.1% of the total variance (PC1 49.3%, PC2 28.3%, and PC3 13.5%) (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Figure 5.

Principal component analysis (PCA) of charosphere drivers: ordination of biochar rate, distance, time, pH, DOC, DTPA-Cd, and wheat Cd concentrations in roots and shoots.

PC1 (biochar factor) loaded positively on root Cd (+0.95), shoot Cd (+0.96), and distance (+0.92), and negatively on pH (−0.67) and DOC (−0.83), confirming that alkalinity and soluble organic ligands released from the char simultaneously mobilize dissolved organic matter yet precipitate or complex Cd, thereby reducing plant uptake. PC2 (soil-factor axis) contrasted biochar rate (+0.87) and DTPA-Cd (-0.90), indicating that Cd availability is highest immediately adjacent to the char particle but declines steeply within 8 mm as pH rises and functional-group density increases. PC3 captured temporal dynamics (+0.92), revealing that Cd immobilization strengthens with residence time as slow alkaline dissolution of mineral ash and progressive oxidation of biochar surfaces create additional metal-binding sites[33,34]. Thus, Cd within the charosphere is alternately activated by low molecular weight organic acids (citrate, oxalate) and re-passivated by alkaline ash and particulate sorption, a dualism that requires ≥ 28 d to reach equilibrium. The magnitude of the pH gradient (ΔpH ≈ 1.2 units over 2 mm) and the strong positive correlation between ash content, electrical conductivity, and the spatial extent of the charosphere suggest that feedstock selection and pyrolysis temperature are critical design variables for maximizing in-situ Cd stabilization while maintaining plant available nutrients[34].

-

Over 28 d, wheat-straw biochar (450 °C) created a 2–8 mm 'charosphere' in which Cd bioavailability and wheat uptake were rapidly and persistently suppressed. Within this micro-zone, pH increased by up to 0.36 units, dissolved organic carbon increased by 69%, and oxygen-rich functional groups accumulated. Moreover, these changes lowered DTPA-extractable Cd by 3.2%–14.2% in the first 2 mm. Immobilization improved with higher amendment rates (2.5%–7.5%), yet was already significant at the lowest dose, indicating a surface-controlled rather than mass-dependent process. SEM-EDS and XPS showed Cd co-localized with Si–O, Fe–O, –COOH, and –OH moieties on the weathered but carbon-rich matrix, confirming that inner-sphere complexation and Cd–(Fe/Al)–O–C ternary bridging dominate Cd retention. Thus, Cd concentrations in wheat shoots and roots were reduced by 5%–28% and 2%–46%, respectively, relative to the 10 mm bulk soil. Principal component analysis attributed 77.6% of the variance in Cd bioavailability to alkalinity plus DOC (PC1) and to biochar rate versus distance (PC2), whereas a third component (PC3) revealed that ongoing surface oxidation and ash-driven alkalinity continued to enhance Cd fixation beyond 21 d. These findings provide the first quantitative evidence that microscale charosphere engineering can decouple Cd mobility from plant uptake in contaminated soils. Field application should therefore place biochar within 2 mm of seeds and favor Si-, Fe-, and alkaline-rich feedstocks to maximize in-situ Cd stabilization without compromising nutrient supply.

The chemical properties, FTIR, and SEM were performed in the Analytical and Testing Center of Yancheng Institute of Technology.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/scm-0025-0016.

-

Not applicable.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Liqiang Cui, Wei Wang: methodology, investigation, writing − review & editing, data curation, writing − original draft. Guixiang Quan, Yuming Liu: data curation, validation. Jinlong Yan: conceptualization, funding acquisition, writing − review & editing. Hui Wang: methodology, resources. Kiran Hina, Qaiser Hussain: investigation, methodology, supervision, writing − review & editing. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

-

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 21677119, 22006127, and 41501339), and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (Grant No. BK20221407), as well as the Yancheng City Science and Technology Key R&D (Grant No. YCBE202308).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

The biochar charosphere was the key microzone in soil.

The charosphere greatly enhanced Cd immobilization.

Biochar provides environmental benefits through close-range contact.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- The supplementary files can be downloaded from here.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Cui L, Wang W, Quan G, Wang H, Hina K, et al. 2026. Biochar-induced charosphere microenvironment modulates soil cadmium bioavailability and wheat uptake. Sustainable Carbon Materials 2: e004 doi: 10.48130/scm-0025-0016

Biochar-induced charosphere microenvironment modulates soil cadmium bioavailability and wheat uptake

- Received: 24 October 2025

- Revised: 15 December 2025

- Accepted: 21 December 2025

- Published online: 28 January 2026

Abstract: When biochar is mixed with soil, it creates a distinct microenvironment, charosphere, within a few millimeters of each particle. Here, physical, chemical, and biological processes are decoupled from those of the bulk soil, providing a local control point for heavy metal mobility and plant uptake. These spatiotemporal effects were examined in a Cd-contaminated soil using a novel microcolumn that allowed 2-mm-resolution sampling for 28 d after amendment with wheat-straw biochar (450 °C). Relative to the unamended bulk (> 10 mm), the charosphere (≤ 8 mm) rapidly became more alkaline (pH increasing by 0.01–0.36 units) and carbon-rich (DOC increasing by 14.7%–69.1%). The steepest changes occurred within 2 mm of the particle surface, where DTPA-extractable Cd reduced by 3.2%–14.2%. The magnitude of Cd immobilization increased with biochar rate (2.5–7.5 wt%) and declined sharply with distance. Surface functional group chemistry, DOC release, and proximity jointly governed these gradients. Cd concentrations in wheat shoots and roots decreased by 5.3%–28.3% and 2.3%–46.3%, respectively, across the 2–8 mm zone vs the 10 mm control. Thus, microscale placement of biochar, rather than bulk soil loading, dictates its capacity to limit Cd uptake, and higher application rates intensify the effect by expanding the reactive charosphere volume.

-

Key words:

- Charosphere /

- Biochar /

- Cd /

- Bioavailability /

- Uptake