-

As key plant-growth nutrients, nitrogen and phosphorus have fueled the widespread use of nitrogen- and phosphorus-based fertilizers. However, extensive human utilization and improper management have resulted in significant emissions of nitrogen and phosphorus ions (NH4+ and PO43−) into the environment. Primary sources include agricultural activities and the discharge of domestic and industrial wastewater[1,2]. Excessive NH4+ and PO43− in water bodies cause eutrophication, leading to environmental pollution. This disrupts the balance of nutrients in aquatic ecosystems, thereby damaging them[3−5]. Currently, there are multiple methods for removing NH4+ and PO43− from water. Among such pollution control approaches, adsorption distinguishes itself as a widely adopted method due to its straightforward operation, quick process, and remarkable efficiency[3,6].

Derived from the anaerobic pyrolysis of biomass feedstocks, biochar is a solid carbonaceous material characterized by superior adsorption performance[7]. Its high porosity, ample specific surface area (SSA), good modifiability, as well as chemical attributes like oxygenated functional groups and unsaturated bonds, render it a widely used candidate for environmental pollutant abatement[8]. In biochar modification research, numerous scholars have employed diverse feedstocks and modification techniques to enhance its adsorption capacity for NH4+ and PO43−. For example, Wang et al. prepared magnesium-loaded modified synthetic sludge-based biochar from anaerobic digestion sludge to remove PO43− from aqueous solutions. Results demonstrated effective PO43− removal under acidic conditions[9]. Jiang et al. prepared Mg-modified biochar from six different feedstocks for removing NH4+ and PO43− from water. According to kinetics and thermodynamics research, cassava straw and banana straw biochar both exhibited high adsorption potential[10]. Li et al. prepared Fe-modified biochar using FeCl3 as a modifier and applied it to adsorb NH4+ and PO43−. This study involved multiple adsorption mechanisms[11]. In summary, existing studies indicate that through modification and composite techniques, the adsorption performance of biochar toward NH4+ and PO43− has been effectively enhanced, with adsorption mechanisms gradually becoming clearer. However, biochar prepared from different raw materials and modification methods exhibits varying adsorption capacities for NH4+ and PO43−. Compared to elements like Fe, Al, and Mg, calcium-based modified biochar, represented by calcium hydroxide, exhibits a strong affinity for NH4+ and PO43−, significantly enhancing adsorption efficiency for these species[5,12−15]. Moreover, calcium is inexpensive, non-hazardous to ecosystems, and widely distributed in nature. Thus, calcium-modified biochar exhibits excellent environmental adaptability and safety, facilitating its long-term functionality in aquatic environments and making it an ideal metal element for biochar modification[16,17]. Moreover, biochar adsorbing PO43− (primarily composed of Ca5(PO4)3(OH)) is widely applied as a phosphorus fertilizer in soil[17,18]. Therefore, in this study, Ca(OH)2 was selected as the modifier.

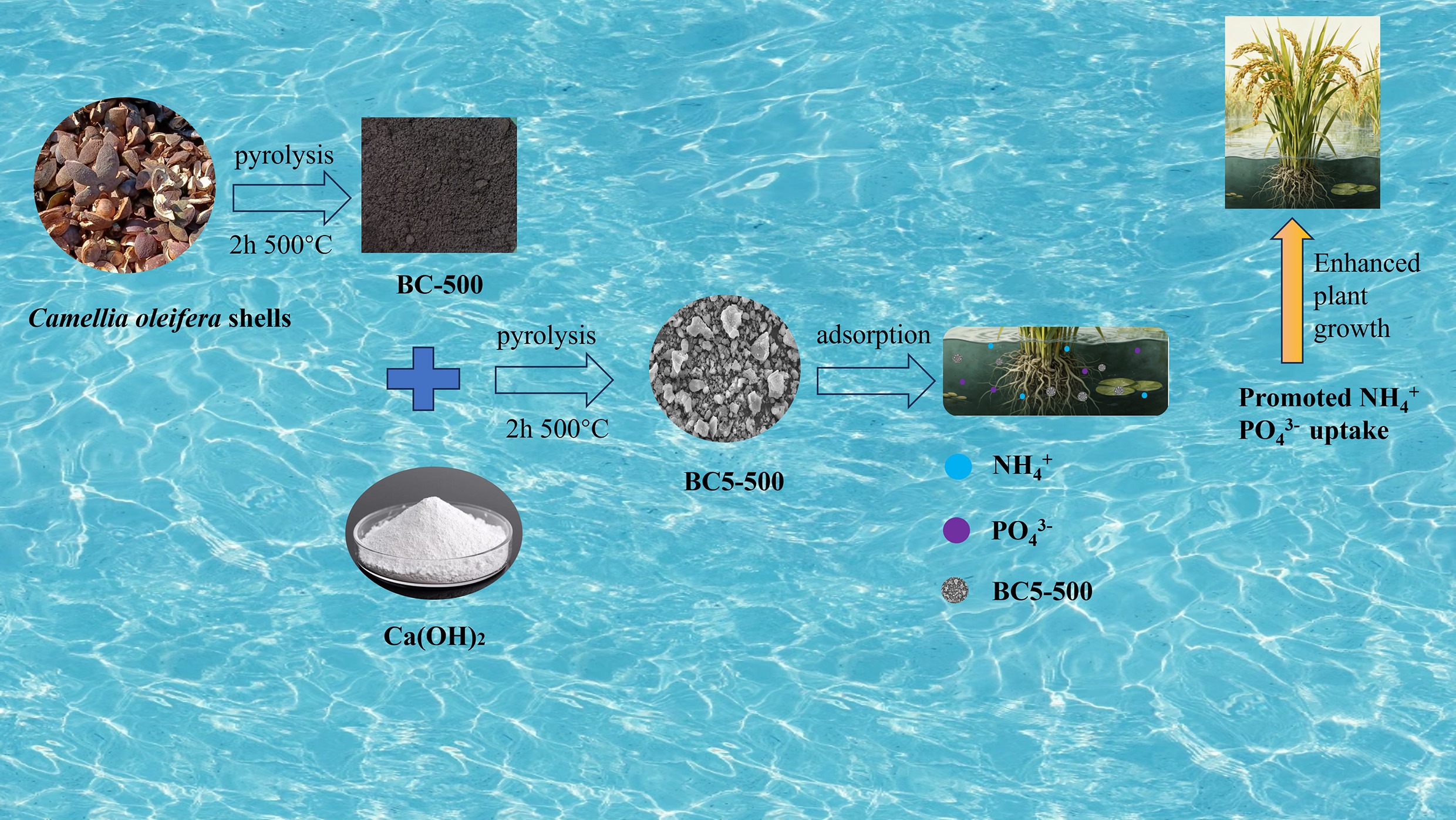

Camellia oleifera is a plant species belonging to the genus Camellia within the family Theaceae. The area used for Camellia oleifera production in China reached approximately 4.67 million hectares in 2023, projected to exceed 6 million hectares by 2025[19]. The processing of Camellia oleifera generates substantial shell waste that is difficult to manage, leading to resource wastage and environmental hazards. The rational utilization of discarded Camellia oleifera shells has become a critical issue for advancing the sustainable development of the Camellia oleifera sector[20]. However, Camellia oleifera shells possess high lignin and carbon content, making them an excellent raw material for producing carbon-based functional materials[21]. Therefore, this study utilizes Camellia oleifera shells as biomass feedstock to produce biochar, thereby unlocking new value for agricultural and forestry waste through circular utilization and writing a green chapter of 'turning waste into treasure'.

This study modified Camellia oleifera shell biochar using Ca(OH)2 as a biochar modifier. It then adsorbed NH4+ and PO43− in aqueous solutions, investigating the effects of time, initial concentration, solution pH, and reaction temperature on the adsorption of NH4+ and PO43− by the modified biochar. Adsorption experiments were also conducted on NH4+ and PO43− from actual swine wastewater. Finally, XPS and FT-IR characterizations were employed to elucidate the adsorption mechanisms of NH4+ and PO43− by the modified biochar. This research elucidates the adsorption patterns, mechanisms, and environmental influences on NH4+ and PO43− by biochar, aiming to offer experimental proof of the adsorption mechanisms of natural compounds comprising phosphorus and nitrogen. It also offers insights for managing organic pollutants in the environment, protecting resources, and promoting resource utilization.

-

Potassium antimony tartrate (98%), ascorbic acid (99.99%), and calcium hydroxide (≥ 95%) were purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. Potassium dihydrogen phosphate (99.5%), Ammonium molybdate (99.0%), Ammonium chloride (99.5%), and Dicyandiamide (AR) were purchased from Shanghai McLean Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. Camellia oleifera shells were obtained from Tianzhu County, Guizhou Province, China.

Biochar and modified biochar preparation

-

The collected Camellia oleifera shells were repeatedly washed with deionized water to eliminate surface dust and soluble impurities. The cleaned material was then dried in an oven at 105 °C for 24 h to produce a constant weight. The dried shells were ground and sieved through a 40-mesh (aperture of approximately 0.45 mm) screen for further use.

A 10 g portion of the sieved Camellia oleifera shell powder was placed in a tube furnace. The sample was heated to 500 °C at a rate of 5 °C·min−1 under a nitrogen atmosphere and then pyrolyzed at that temperature for 2 h. The solid product was sieved through a 100-mesh screen (aperture of approximately 0.15 mm). The resulting material was labeled as BC-500 and collected for subsequent use.

Biochar derived from pyrolyzed Camellia oleifera shells was chemically modified using various reagents to produce a total of nine modified samples. For specific reagents and their quantities, please refer to the Supplementary Table S1. The general preparation procedure is described below. BC-500 and Ca(OH)2 were mixed at a mass ratio of 1:2, followed by deionized water at a solid to fluid ratio of 1:10 g·mL−1.The mixture was stirred for 24 h at 25 °C and 500 rpm, followed by vacuum filtration. The resulting solid was washed with deionized water and dried at 80 °C for 12 h.

The dried material underwent secondary pyrolysis in a tube furnace under conditions identical to those used for BC-500 preparation. The final Ca(OH)2-modified biochar was designated as BC5-500.

Testing and characterization

-

The samples of biochar were described. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Apreo 2) was used to observe surface morphology. The specific surface area and pore structure were determined via N2 adsorption-desorption analysis (TriStar II Plus 3030). Functional groups were identified by Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR, Nicolet iS10) in the range of 4,000 to 400 cm−1. The crystal structure was analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD, SmartLab 9), and the surface elemental composition was probed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Escalab 250Xi). The concentrations of NH4+ and PO43− in solution were measured using a UV-vis spectrophotometer (UV-5500PC).

Adsorption experiments of biochar on NH4+ and PO43−

-

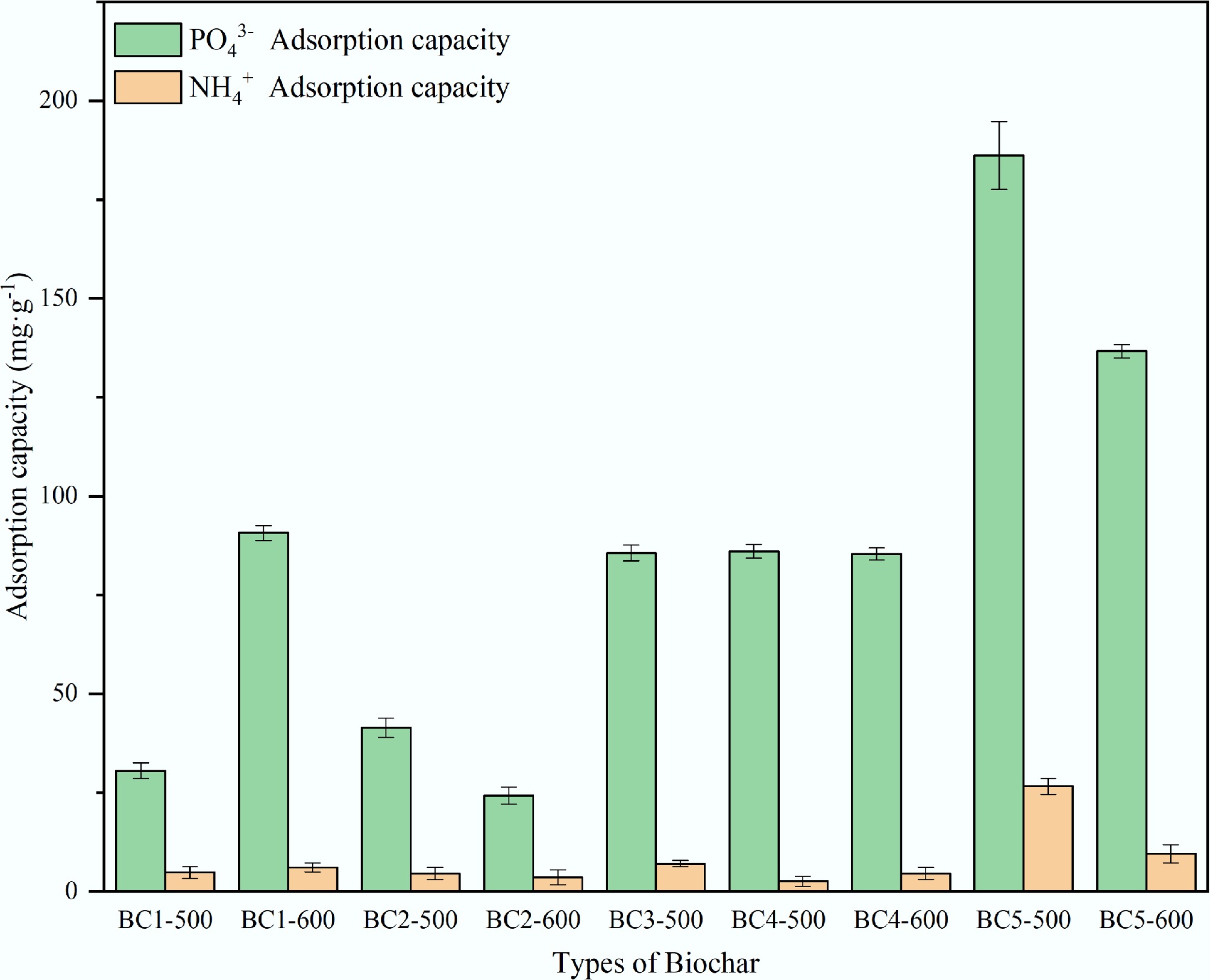

Preliminary experiments were carried out to screen the most effective adsorbent for the removal of NH4+ and PO43− from nine prepared biochar samples (Fig. 1). NH4+ and PO43− stock solutions were prepared using NH4Cl and KH2PO4, with initial concentrations of 100 and 600 mg·L−1, respectively. The initial pH of each solution was adjusted to 10 for NH4+ and 6 for PO43− using 0.1 mol·L−1 NaOH or HCl. For the adsorption experiments, 0.05 g of modified biochar was added to 30 mL of the corresponding solution and shaken at 150 rpm and 25 °C. The adsorption time was set to 120 min for NH4+ and 360 min for PO43−. After adsorption, the quantities of NH4+ and PO43− were measured using UV-Vis spectrophotometry after the filtrate was separated using a 0.22 μm membrane filter. BC5-500 showed the highest adsorption capacity, reaching 26.66 mg·g−1 for NH4+ and 186.18 mg·g−1 for PO43−. Its performance was further compared with that of modified biochars reported in other studies for NH4+ and PO43− adsorption (Table 1). Given its considerable potential, BC5-500 was selected for subsequent systematic investigation.

Table 1. Comparison among modified biochars for NH4+ and PO43− adsorption

Biochar name Adsorbate (mg·g−1) Reaction kinetics pH range Ref. NH4+ PO43− BS600 114.64 31.05 Pseudo-second-order kinetics 8.5–9.7 [22] MgB 15.22 − Pseudo-first-order kinetics 6.0–8.0 [23] SB > 28.2 > 120 Pseudo-second-order kinetics Unadjusted pH [24] MgB-A 37.72 73.29 Pseudo-second-order kinetic 4.0–8.0 [25] Desorption experiment

-

To assess the reusability of BC5-500, cyclic adsorption-desorption experiments were performed. In each cycle, 0.10 g of BC5-500 was first subjected to adsorption under optimal conditions. Subsequently, the spent adsorbent was collected by filtration. The contaminant-laden BC5-500 was then subjected to static desorption in 50 mL of a 1.5 mol·L−1 NaOH solution at 25 °C for 2 h. After each desorption process, the material was filtered, cleaned with deionized water, and dried at 80 °C to prepare it for the subsequent cycle. Five successive cycles of this full adsorption-desorption process were carried out.

Data analysis

-

All experiments were performed in triplicate. Following the adsorption process, the solutions were filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane. The following equations were utilized to determine the adsorption capacity and removal efficiency based on the residual concentrations of NH4+ and PO43−:

$ \mathrm{Qt}=\dfrac{\left(C_0-C\right)\ \times\ V}{m} $ (1) $ R=\dfrac{{C}_{0}-C}{{C}_{0}}\times 100{\text{%}}$ (2) In the equation, Qt denotes the adsorption capacity (mg·g−1); R represents the removal efficiency (%); C0 is the initial concentration of the adsorbate (mg·L−1); C is the equilibrium or residual concentration after adsorption (mg·L−1); V refers to the volume of the solution (L); and m is the mass of the adsorbent (g).

-

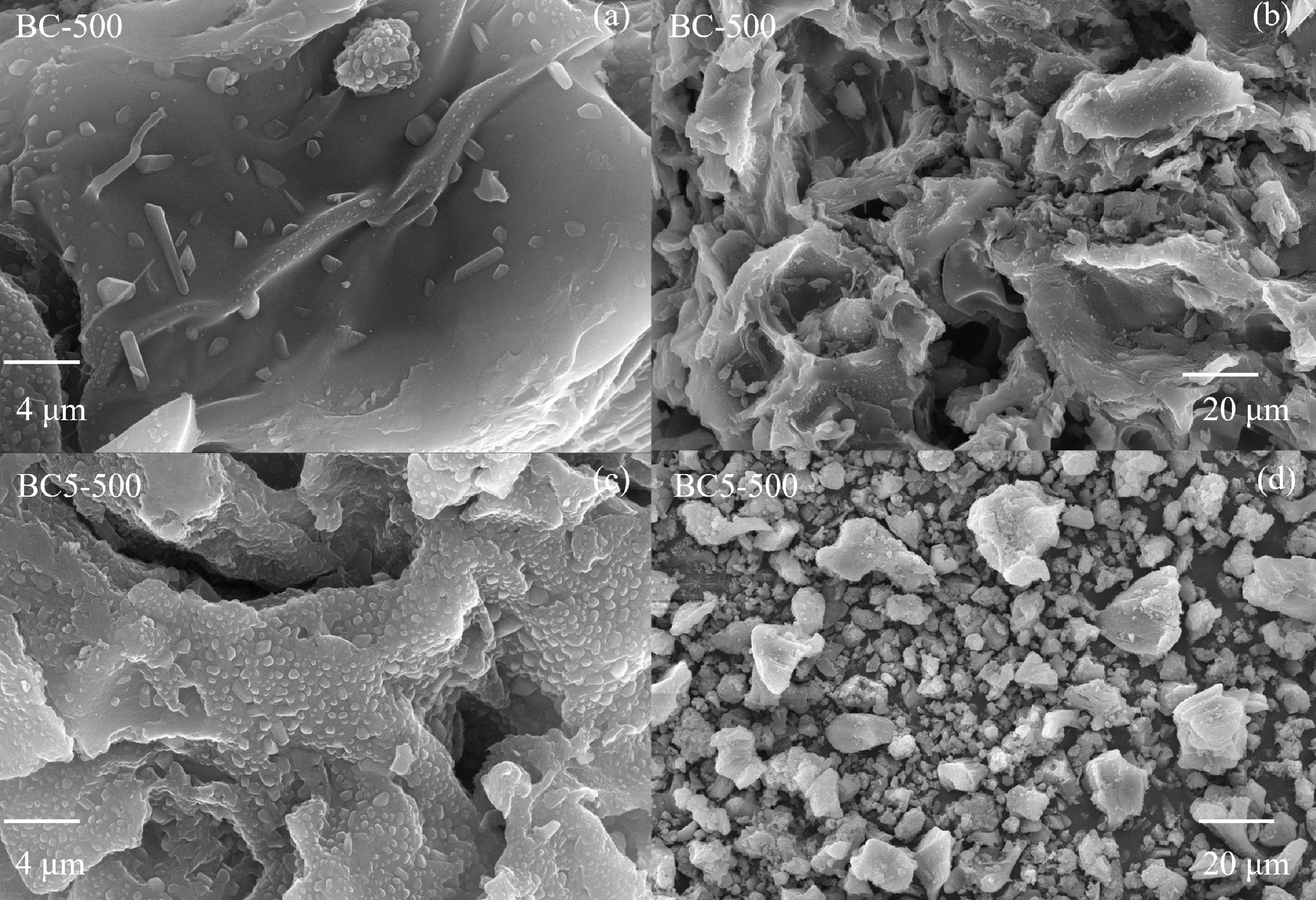

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was employed to analyze the morphologies of BC-500 and BC5-500. The BC-500 surface appeared relatively smooth, with irregular lumpy particles adhering to it. These particles likely originated from mineral components that were incompletely carbonized (Fig. 2a, b). After modification via Ca(OH)2 alkaline etching, the BC5-500 surface became rough, exhibiting a multilayered wrinkled structure (Fig. 2c, d). These wrinkles are expected to provide abundant reaction sites for subsequent adsorption processes.

Figure 2.

SEM images of (a), (b) the biochar (BC-500), and (c), (d) the Ca(OH)2-modified biochar (BC5-500).

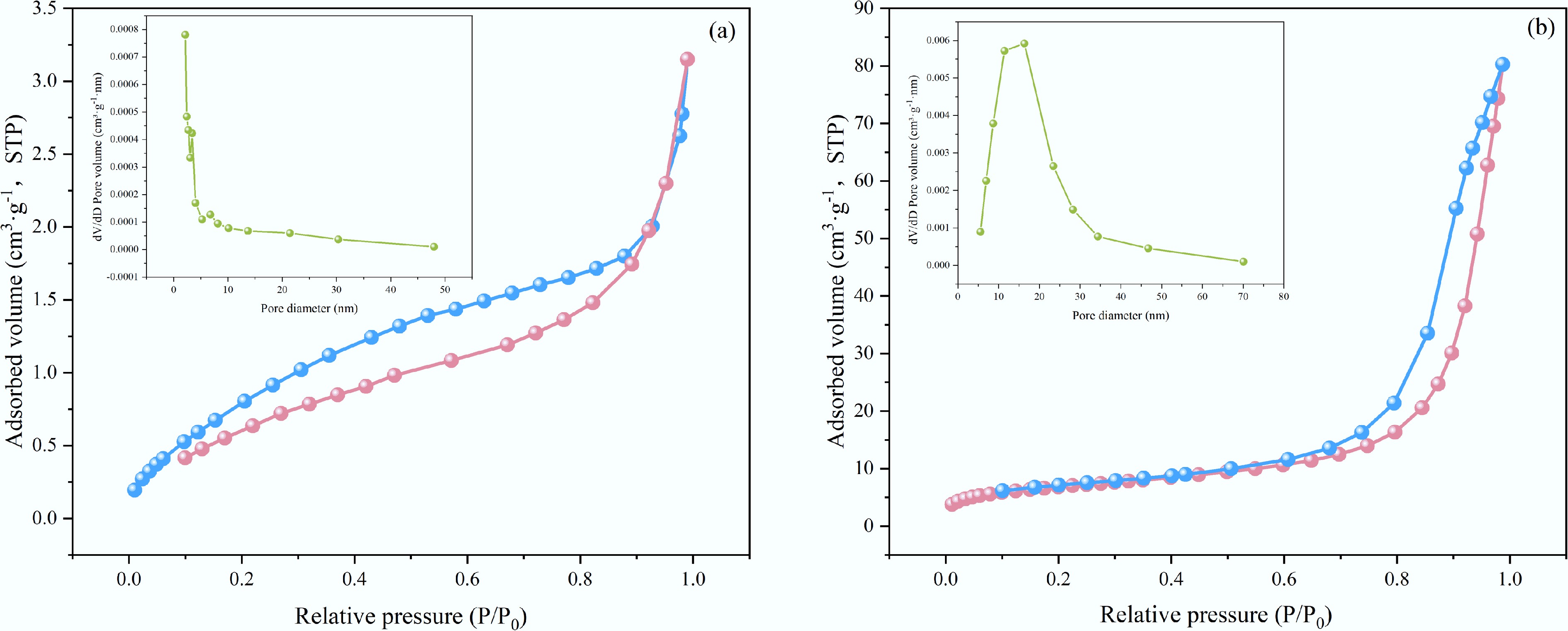

The Brunauer-Emmett-Teller method was used to examine the pore structure of the materials. The nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms of both BC-500 and BC5-500 exhibit Type IV behavior and display H1 hysteresis loops, indicating that both materials possess mesoporous structures with relatively concentrated pore size distributions (Fig. 3). As evident from the pore size distribution diagram and Table 2 data, Ca(OH)2 etching modification significantly increased the specific surface area of the biochar while introducing calcium active sites. This synergistic effect enhanced the adsorption capacity of BC5-500 for both NH4+ and PO43−.

Table 2. Physical properties of BC-500 and BC5-500

Biochar name SBET (m2·g−1) Total pore volume (cm3·g−1) Average pore size (nm) BC-500 3.71 0.0048 5.24 BC5-500 4.29 0.0079 20.01 Evolution of functional groups upon biochar adsorption

-

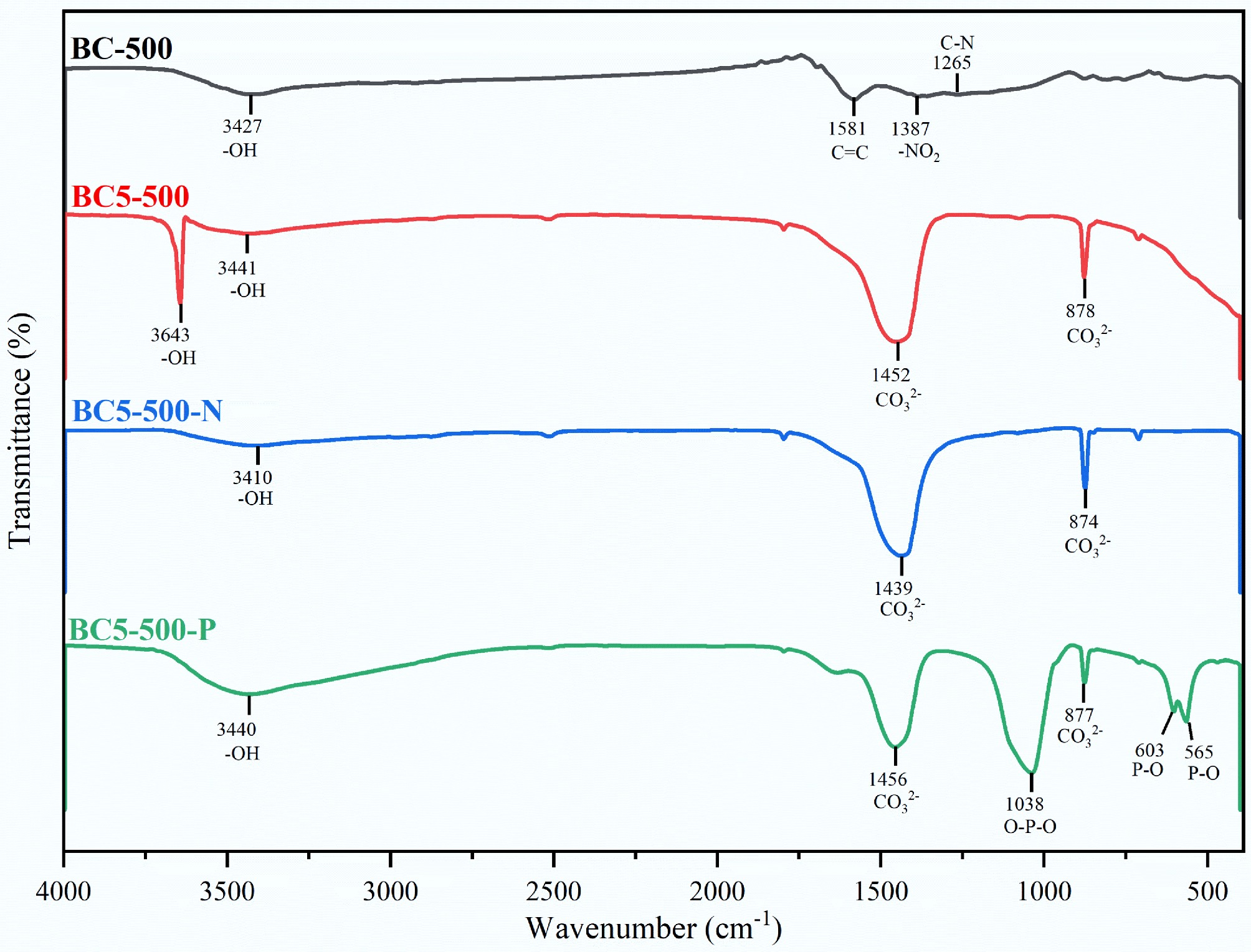

FT-IR analysis of the material's chemical structure yielded the results shown in Fig. 4. The characteristic peaks at 3,427, 1,581, 1,387, and 1,265 cm−1 in the unmodified material BC-500 are attributed to functional groups (–OH, C=C, –NO2, –C–N) in the pyrolysis residues of lignin and cellulose[6,26−31]. Following Ca(OH)2 modification, the spectrum of BC5-500 exhibits significant changes. New absorption peaks appeared at approximately 878, 1,452, and 3,643 cm−1, corresponding to Ca–O vibrations, asymmetric CO32− stretching, and Ca-OH stretching, respectively. This indicates that calcium species were converted to CaO and partially carbonated to CaCO3 during pyrolysis, while residual or hydrated hydroxyl groups remained on the surface[6,26−32]. These results confirm the successful loading of Ca(OH)2 onto the biochar surface. Following NH4+ adsorption, the –OH vibration peak of water in the BC5-500-N spectrum was significantly weakened or disappeared, likely due to hydrogen bonding or ionic-dipolar interactions between oxygen-containing functional groups and NH4+[6,26−32]. After PO43− adsorption, the residual Ca–OH peak in the BC5-500-P spectrum disappeared, and new peaks appeared at 603, 565, and 1,038 cm−1, attributed to the bending vibration (P–O) and symmetric stretching vibration (O-P-O) of PO43−, respectively. This indicates that PO43− undergoes surface coordination with calcium active sites or forms calcium phosphate precipitates[33]. This change further confirms that PO43− adsorption by the modified biochar is dominated by chemisorption.

Figure 4.

FT-IR spectra of BC-500, BC5-500, and their derivatives after adsorption of NH4+ (BC5-500-N) and PO43− (BC5-500-P).

XRD analysis of biochar modification and adsorption

-

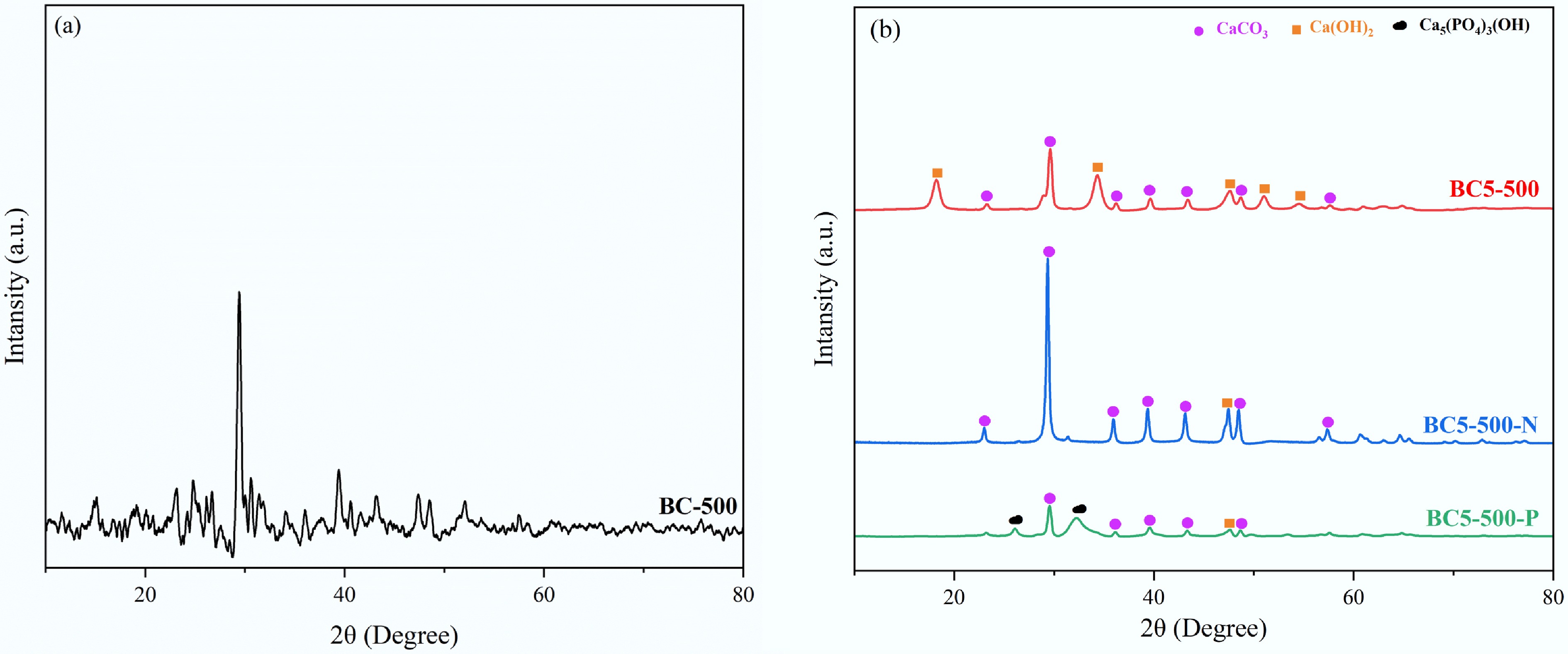

The crystalline structure of the material was analyzed via XRD. BC-500 exhibited broadened diffraction peaks at 2θ = 29.9°, corresponding to the amorphous carbon matrix formed after pyrolysis and any poorly crystalline mineral components potentially present within it (Fig. 5a)[16,34,35]. Following modification, several new diffraction peaks appeared in the BC5-500 spectrum. Upon comparison with standard patterns, the diffraction peaks at 2θ = 23.1°, 29.4°, 36.0°, 39.4°, 43.2°, 48.5°, and 57.4° match those of the CaCO3 standard pattern (PDF#98-000-0141); while those at 2θ = 18.2°, 34.4°, 47.5°, 51.2°, and 54.8° matched the Ca(OH)2 standard card (PDF#97-009-1882). These results confirm the successful incorporation of a composite calcium phase comprising CaCO3 and Ca(OH)2, whose structure provides alkaline sites and precipitation active centers for subsequent adsorption processes[36].

Figure 5.

XRD patterns of (a) BC-500, and (b) BC5-500 before and after adsorption (BC5-500, BC5-500-N, and BC5-500-P).

The XRD pattern of BC5-500-N simultaneously reveals both CaCO3 and Ca(OH)2 phases, with the diffraction peak intensity of Ca(OH)2 significantly diminished. This may be attributed to the oxygen-containing functional groups on the BC5-500 surface chemically adsorbing NH4+ from the water (Fig. 5b). The XRD pattern of BC5-500-P exhibits a new phase, whose characteristic diffraction peaks at 2θ = 25.9° and 32.3° align with the standard pattern for hydroxyapatite (Ca5(PO4)3(OH)) (PDF#97-008-1442), indicating that PO43− and Ca2+ combine on the material surface to form amorphous calcium phosphate, which subsequently recrystallizes into the thermodynamically more stable hydroxyapatite at the alkaline interface (Fig. 5b)[16,34,37]. This process further confirms that the biochar within BC5-500 functions as a multifunctional carrier and reaction promoter. In summary, BC5-500 exhibits pronounced adsorption capacity for both NH4+ and PO43−, with the adsorption process accompanied by the formation of novel compounds.

XPS analysis before and after biochar adsorption

-

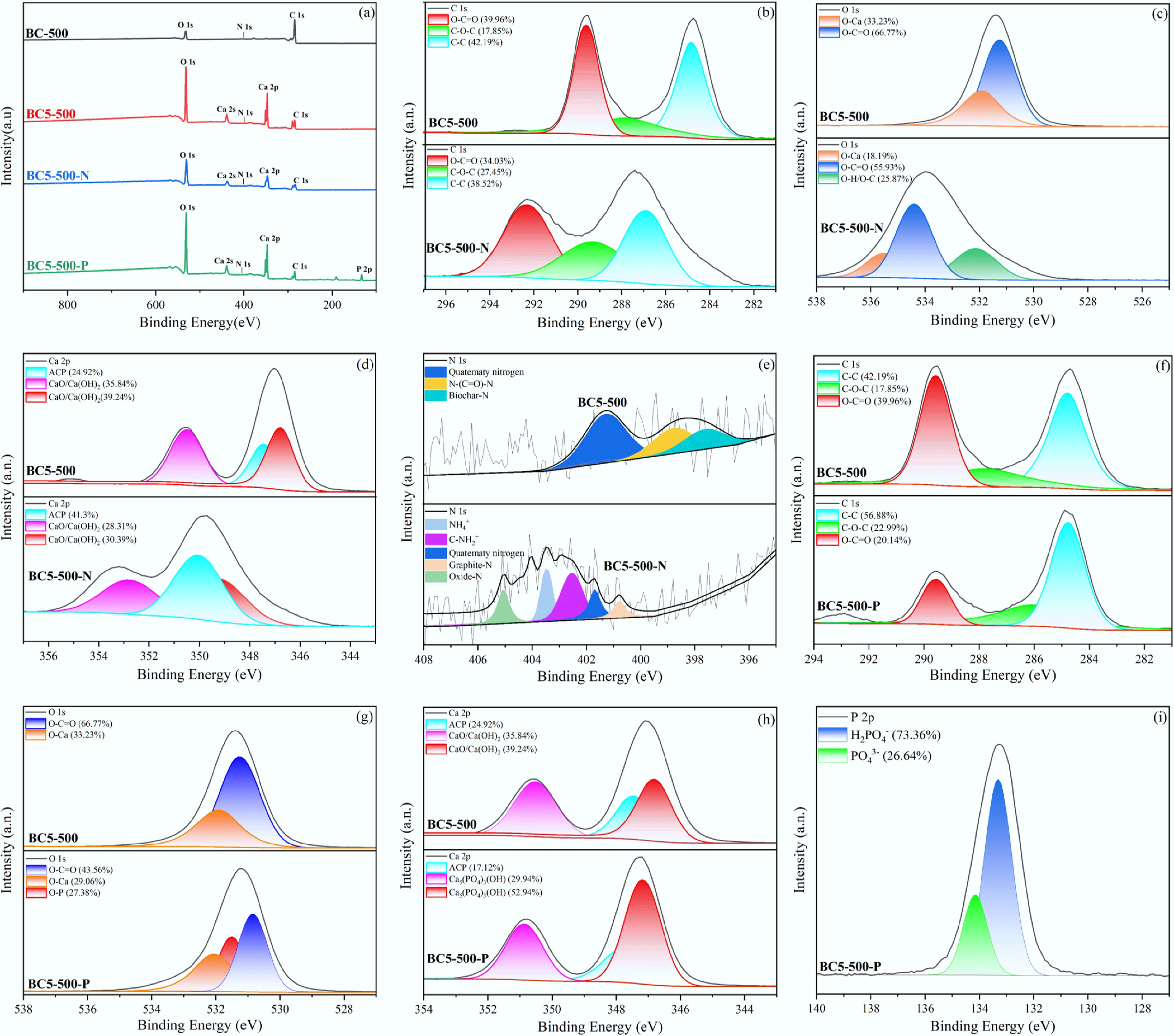

To investigate structural changes in materials during PO43− adsorption, XPS characterisation was performed on BC-500, BC5-500, BC5-500-N, and BC5-500-P.

XPS full-spectrum analysis indicates that C, N, O, and Ca elements were detected in all synthesised materials and their post-adsorption samples. Notably, a new characteristic P peak was only observed in the spectrum of BC5-500-P (Fig. 6a). This result directly confirms the successful synthesis of the adsorbent BC5-500 and indicates its adsorption capacity for NH4+ and PO43−. Analysis of the C 1s spectrum for BC5-500-N in Fig. 6b reveals that, owing to incomplete pyrolysis, oxygen-containing functional groups and aromatic structures remain partially preserved within the biochar. Following NH4+ adsorption, the O–C=O and C=C contents in BC5-500-N decreased by 5.96% and 3.67%, respectively, while the C–O–C content increased by 9.6%. This shift likely arises from NH4+ adsorption, altering the local chemical environment of carbon. The O 1s spectra of BC5-500 and BC5-500-N (Fig. 6c) reveal reduced lattice oxygen content alongside the emergence of a peak at 532.6 eV, attributed to O–H/O–C[38,39]. The Ca 2p spectra for BC5-500 and BC5-500-N are shown in Fig. 6d. BC5-500 exhibits Ca-O-assigned peaks at 346.9 and 350.6 eV, indicating successful etching of Ca(OH)2 onto the biochar surface, consistent with literature reports[40]. In BC5-500-N, the Ca 2p peak shifts blue overall and decreases in intensity due to interactions between oxygen-containing groups and NH4+. To better understand the adsorption procedure, N 1s spectra of BC5-500 and BC5-500-N were analysed (Fig. 6e). Peaks at 397.6, 398.7, and 401.2 eV in BC5-500 corresponded to intrinsic biochar nitrogen, N–(C=O)–N, and quaternary nitrogen structures, respectively[38−42]. Following NH4+ adsorption, BC5-500-N exhibits new peaks at 400.9, 402.5, 403.2, and 405.4 eV, which are attributed to graphitic nitrogen, C-NH2+, NH4+, and oxidised nitrogen species, respectively[38,41,42]. These results indicate that NH4+ adsorption on BC5-500 is mediated by Ca as the active centre, achieved through modulation of the local electronic structure.

Figure 6.

XPS analysis of BC-500 and BC5-500 before and after adsorption: (a) survey spectra, (b)–(e) high-resolution C 1s, O 1s, Ca 2p, and N 1s spectra of BC5-500 and BC5-500-N, (f)–(h) high-resolution C 1s, O 1s, and Ca 2p spectra of BC5-500 and BC5-500-P, and (i) high-resolution P 2p spectrum of BC5-500-P.

Figure 6f compares the C 1s spectra of BC5-500 and BC5-500-P. A distinct redistribution of C–C, C–O–C, and O–C=O bond abundances occurred in BC5-500-P, driven by the formation of surface Ca3(PO4)2. Concurrently, Fig. 6g reveals diminished intensities for the O–C=O and O–Ca peaks in the O 1s spectrum of BC5-500-P, potentially attributable to ion exchange between CO32– and H2PO4–/HPO42–/PO43–[31]. The Ca 2p spectrum of BC5-500-P (Fig. 6h) exhibits new Ca–O peaks at 347.5 and 351.0 eV, indicating that PO43− is chemically bonded to the adsorbent surface. Figure 6i shows the P 2p spectrum of BC5-500-P, exhibiting characteristic double peaks at 133.5 eV (P 2p3/2) and 133.9 eV (P 2p1/2), with relative contributions of 73.36% and 26.64%, respectively. This further suggests that phosphate adsorption may involve a multi-step chemical reaction process.

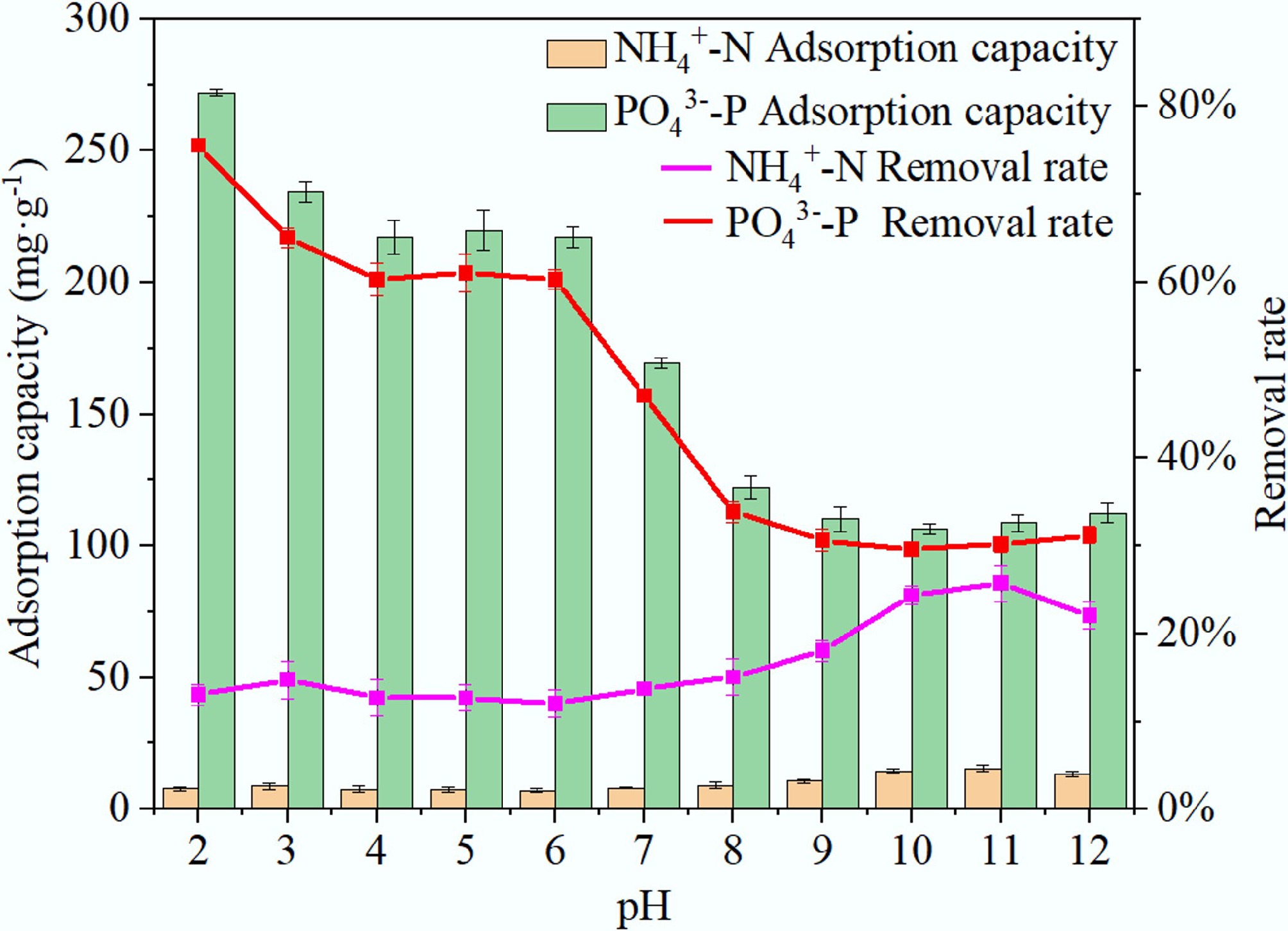

Effect of solution pH

-

The pH of the solution is a key factor influencing the adsorption performance of biochar[43]. As shown in Fig. 7, the adsorption capacity first increases and then decreases with rising pH. It reaches its maximum at pH 11.0 (adsorption capacity of 15.44 mg·g–1 and removal rate of 25.73%), after which it decreases as pH continues to increase. Alkaline conditions favor the adsorption of NH4+. In an acidic environment, numerous H+ battle with NH4+ for adsorption sites on the BC5-500 surface, therefore inhibiting adsorption[44]. For PO43– adsorption, as pH increased, the adsorption capacity decreased. At pH 2.0, PO43– adsorption is most effective, with an adsorption capacity of 172.04 mg·g–1 and a removal rate of 75.58%. This occurs because the form of phosphate present changes with pH: at pH < 2.1, it exists as H3PO4; at 2.1 < pH < 7.2, it primarily exists as H2PO4−; at 7.2 < pH < 12.3, it mainly exists as HPO42–; and at pH > 12.3, PO43– becomes predominant[31]. In acidic conditions, Ca2+ on BC5-500 is more readily precipitated by binding with H2PO4–. This process can be represented by the following equation:

$ \mathrm{Ca}^{ {2+}} +\mathrm{H}_{ \mathrm{2}} \mathrm{PO}_{ {4}}^{-}+ \mathrm{2H}_{ \mathrm{2}} \mathrm{O}\to {\mathrm {CaHPO}}_{ \mathrm{4}}\,\times\, \mathrm{2H}_{ \mathrm{2}} \mathrm{O(} \mathit{s} \mathrm{)+H}^{+} $ (3) However, in neutral and alkaline environments, the abundant OH– in water competes with Ca2+ to preferentially form Ca(OH)2 precipitates. Simultaneously, OH− also competes with HPO42– for adsorption sites, leading to a decrease in phosphorus adsorption capacity[44,45]. Within the experimental pH range, adsorption capacities consistently exceeded 150 mg·g–1, with removal rates surpassing 55%. At pH 2.0 and 11.0, the maximum adsorption capacities for PO43– and NH4+ were achieved, respectively. However, considering the pH conditions in real-world water environments and the need to obtain relatively high adsorption capacities, subsequent experiments for PO43– and NH4+ were conducted at pH 6.0 and 10.0, respectively.

Adsorption kinetics

-

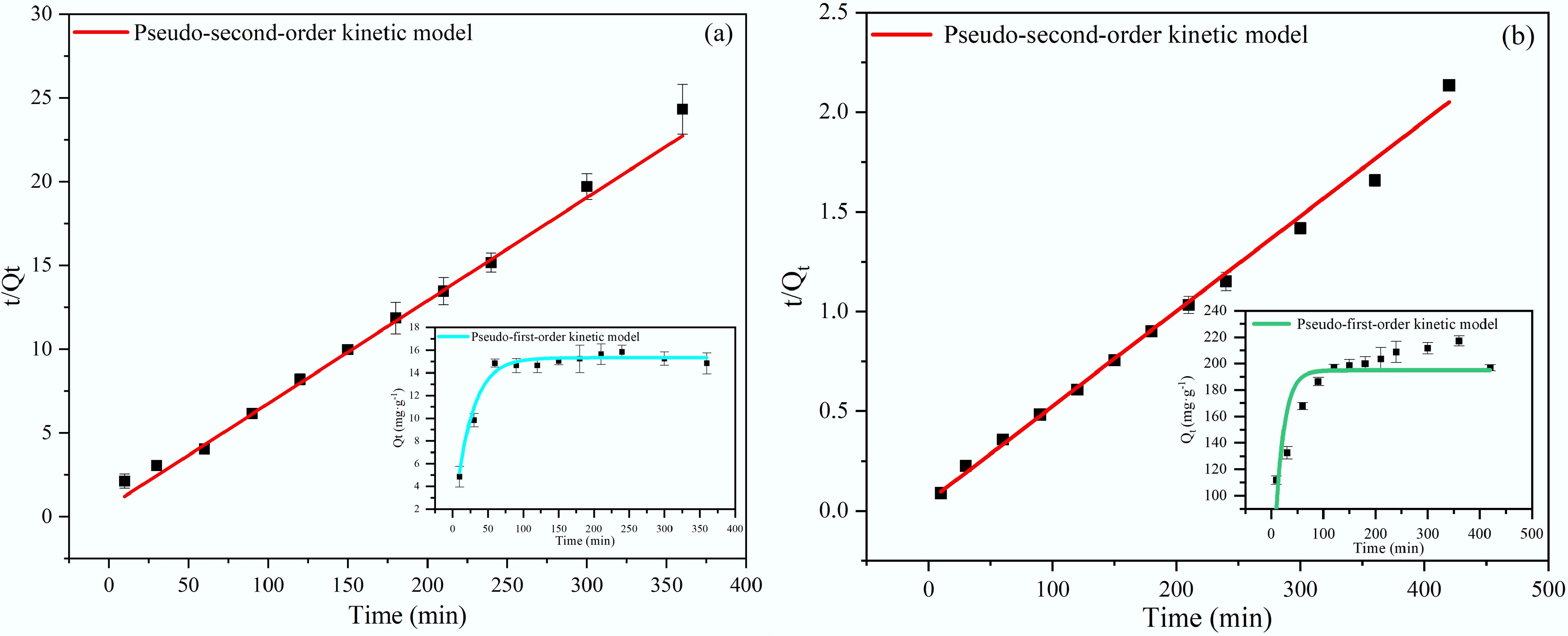

The kinetic adsorption of PO43– and NH4+ by modified biochar was modeled using pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order equations, respectively. Their expressions are shown in Eqs (4) and (5).

$ {\mathrm{Q}}_{\mathrm{t}}={\mathrm{Q}}_{\mathrm{e}}\left(1-{e}^{-{{k}_{1}}t}\right) $ (4) $ \dfrac{t}{{Q}_{t}}=\dfrac{1}{{k}_{2}\times Q_{e}^{2}}+\dfrac{t}{{Q}_{e}} $ (5) In the above equations, Qe and Qt represent the adsorption capacities at equilibrium (mg·g–1), respectively; k1 (min–1) and k2 (g·mg–1·min–1) denote the adsorption rate constants for pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order kinetics, respectively; t (min) is the adsorption time.

The kinetic adsorption profiles of NH4+ and PO43– onto BC5-500 are presented in Fig. 8. The adsorption capacities for both pollutants increase rapidly in the initial stage, attaining equilibrium after approximately 60 and 90 min, respectively. This fast initial uptake rate can be attributed to the abundance of readily accessible active sites on the biochar surface. As adsorption progressed, the availability of these sites gradually decreased, resulting in a decreased adsorption rate until equilibrium was established.

As shown in Table 3, the pseudo-second-order kinetic model provides a substantially better fit than the pseudo-first-order model for both pollutants (R2 > 0.986), and its calculated equilibrium adsorption capacities agreed closely with the experimental values. These results suggest that the adsorption process is likely governed by the number of surface active sites, indicating that chemical adsorption is a major factor[44,46].

Table 3. Kinetic parameters for NH4+ and PO43− adsorption onto BC5-500

Biochar name Adsorbate Pseudo-first-order kinetic model Pseudo-second-order kinetic model Qe K1 R2 Qe K2 R2 BC5-500 NH4+ 15.33 0.04148 0.9371 16.27 0.00012 0.9863 PO43– 194.94 0.06142 0.7500 209.65 0.00047 0.9962 Adsorption isotherms

-

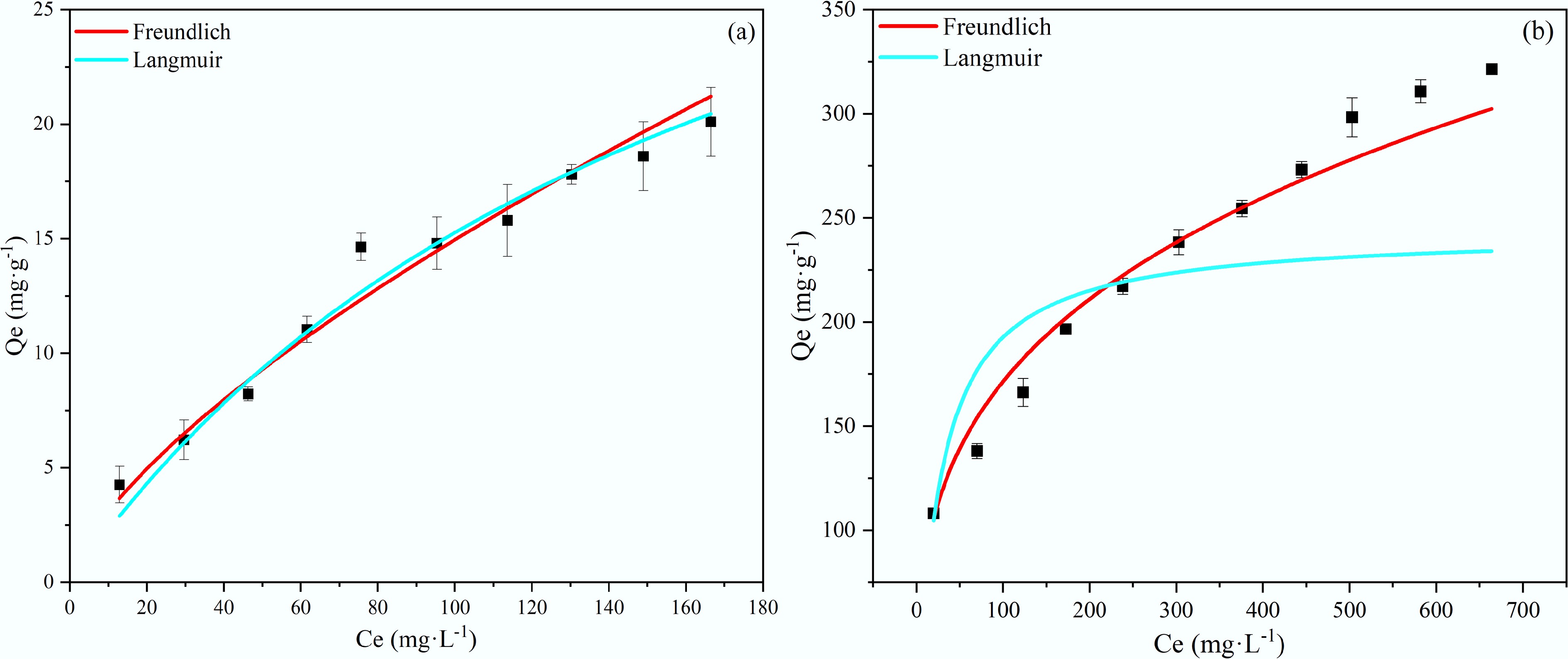

The adsorption equilibrium data were analyzed using the Langmuir and the Freundlich isotherm models. The Langmuir model describes monolayer adsorption onto a homogeneous surface, while the Freundlich isotherm is an empirical model typically applied to characterize multilayer adsorption on heterogeneous surfaces. The corresponding fitted curves are presented in Fig. 9, with the mathematical expressions of the models given as follows:

$ {\mathrm{Q}}_{\mathrm{e}}=\dfrac{{\mathrm{Q}}_{\mathrm{m}}{K}_{L}{\mathrm{C}}_{\mathrm{e}}}{1+{K}_{L}{\mathrm{C}}_{\mathrm{e}}}$ (6) $ {\mathrm{Q}}_{\mathrm{e}}={\mathrm{k}}_{\mathrm{F}}\mathrm{C}_{\mathrm{e}}^{\frac{1}{\mathrm{n}}} $ (7) Qe (mg·g–1) and Qm (mg·g–1) represent the equilibrium adsorption capacity and the theoretical saturation adsorption capacity of the Langmuir model, respectively; Ce denotes equilibrium concentration (mg·L–1); KL represents the Langmuir adsorption constant (L·mg–1); 1/n is the Freundlich adsorption intensity coefficient; KF((mg·g–1)·(mg·L–1)–1/n) is the Freundlich adsorption constant.

The fitting parameters of the adsorption isotherm models are summarized in Table 4. For NH4+, both Langmuir and Freundlich models exhibit good agreement with the adsorption data (R2 = 0.967 and 0.962, respectively), indicating that adsorption did not occur solely on an idealized homogeneous surface. The inherent heterogeneity of biochar, coupled with the contribution of multiple interactions such as ion exchange and surface complexation, likely governed the adsorption behavior. The dimensionless separation factor RL derived from the Langmuir model was 0.64 (0 < RL < 1), confirming the spontaneity and favorable nature of NH4+ adsorption under the experimental conditions[43].

Table 4. Parameters of the adsorption isotherms for NH4+ and PO43– onto BC5-500

Biochar name Adsorbate Langmuir Freundlich Qm KL R2 n KF R2 1/n BC5-500 NH4+ 41.87 0.00574 0.967 1.145 0.632 0.962 0.873 PO43– 243.33 0.0380 0.868 3.335 43.077 0.990 0.300 For PO43–, the adsorption data were better described by the Freundlich model (R2 = 0.990), suggesting an energetically heterogeneous adsorption surface with potential multilayer characteristics. The Freundlich constant 1/n was 0.300 (< 0.5), indicating a very strong surface affinity of BC5-500 toward PO43–[47]. This is primarily attributed to the Ca2+ introduced by the Ca(OH)2 modification, which facilitates effective removal through the formation of insoluble calcium phosphate precipitates (Refer to the XPS characterization analysis). This chemical precipitation mechanism is substantially more dominant than conventional physical adsorption. Thermodynamically, the Freundlich parameter n exceeded 1 for both pollutants, confirming the excellent adsorption capacity of BC5-500 toward both NH4+ and PO43–[48].

Effect of reaction temperature

-

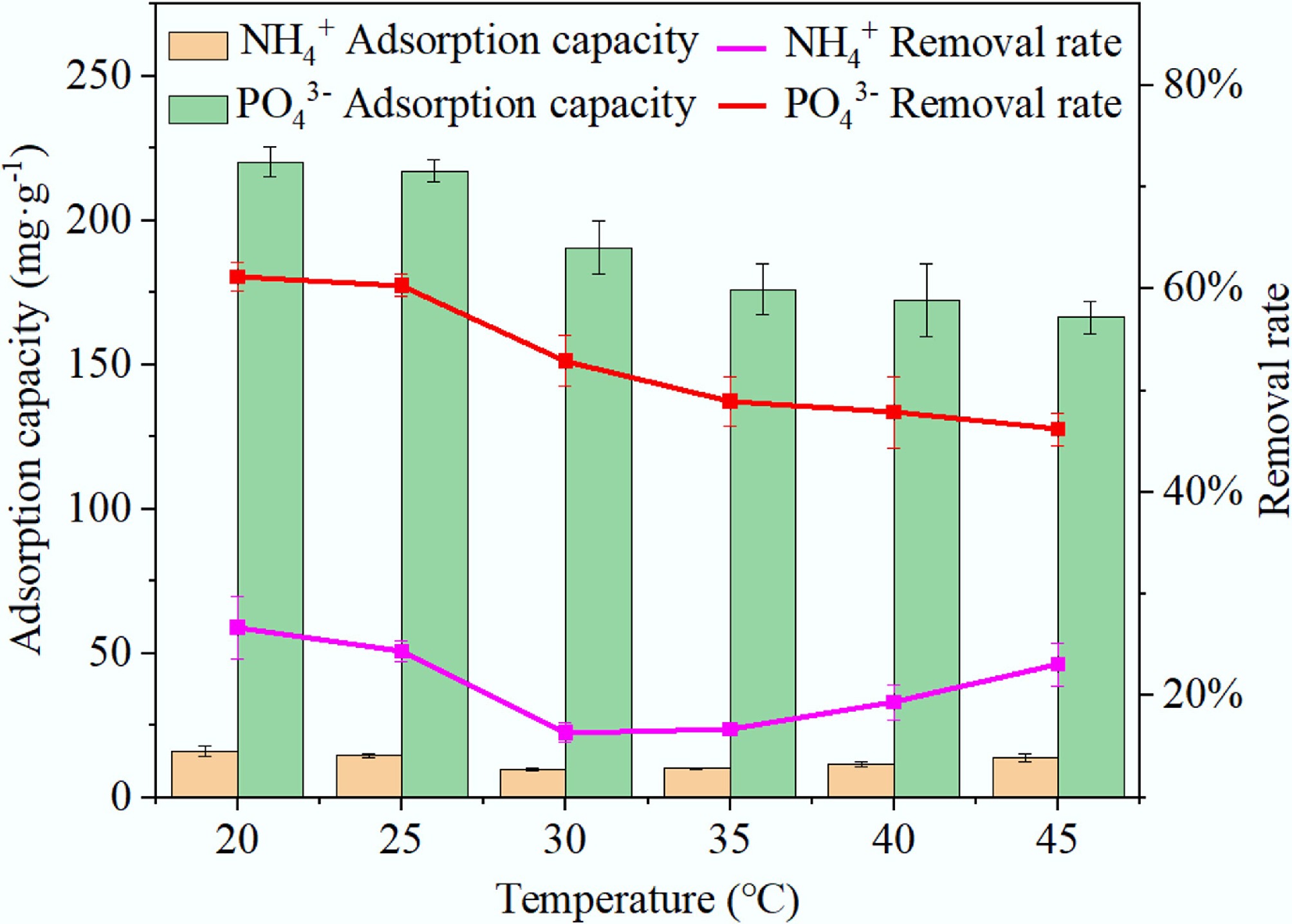

There are two phases to the effect of temperature on NH4+ adsorption performance, as illustrated in Fig. 10. During the initial phase, at temperatures between 20–30 °C, the adsorption capacity and removal efficiency of BC5-500 for NH4+ decrease with increasing temperature, reducing by 4.6 mg·g–1 and 7.67%, respectively. In the second phase, at temperatures between 30 and 45 °C, the adsorption capacity for NH4+ increases with rising temperature. Overall, adsorption performance for NH4+ shows a pattern of declining and then rising. Regarding adsorption performance for PO43–, both adsorption capacity and removal efficiency decreased with increasing temperature. Adsorption capacity dropped from 220.22 to 166.39 mg·g–1, while removal efficiency decreased from 61.17% to 46.22%. This result suggests that elevated temperature significantly inhibits the adsorption process.

Figure 10.

Influence of reaction temperature on the adsorption capacity of BC5-500 for NH4+ and PO43–.

Relevant thermodynamic parameters for the adsorption process were calculated using the following equations[49]:

$ \Delta {G}^{o}=-RT\ln {k}_{0} $ (8) $ \Delta {G}^{o}=\Delta {H}^{o}-T\Delta {S}^{o} $ (9) $\ln {k}_{0}=\dfrac{\Delta {S}^{o}}{R}-\dfrac{\Delta {H}^{o}}{RT} $ (10) In the formula: ΔGo (kJ mol–1) is the standard Gibbs free energy; ΔHo (kJ mol–1) is the standard enthalpy change; ΔSo (J·mol–1 K–1) is the standard entropy change; R is the gas constant; k0 is the adsorption equilibrium constant.

The thermodynamic parameters (ΔG°, ΔH°, and ΔS°) for the adsorption process were determined at various temperatures and are presented in Table 5.

Table 5. Thermodynamic parameters for the adsorption of NH4+ and PO43– onto BC5-500

Biochar

nameAdsorbate Temperature

(°C)K0 ΔG0 ΔH0 ΔS0 BC5-500 NH4+ 293 0.219 3.700 45.645 167.890 298 0.195 4.067 303 0.118 5.390 308 0.121 5.417 313 0.144 5.036 318 0.180 4.535 PO43− 293 0.945 0.1367 –20.896 –71.714 298 0.912 0.228 303 0.675 0.99 308 0.575 1.416 313 0.551 1.551 318 0.517 1.751 For NH4+ adsorption, as the temperature increased to 30–45 °C, ΔH° > 0 and ΔS° > 0, indicating a shift to an endothermic process with increasing entropy. Accordingly, the adsorption capacity rose with temperature, demonstrating a high-temperature-driven characteristic.

For PO43– adsorption, across the entire experimental temperature range (20–45 °C), ΔH° < 0 and ΔS° < 0, corresponding to an exothermic process associated with a reduction in entropy. The capacity for adsorption dropped as the temperature rose, indicating a preference for lower temperatures[48−50]. The calculated ΔG° values were also positive in this case.

In general, the sign of ΔH° governs the temperature dependence of adsorption capacity: exothermic processes (ΔH° < 0) are favored at lower temperatures, whereas endothermic processes (ΔH° > 0) are enhanced at higher temperatures. Although all computed ΔG° values were positive—reflecting thermodynamic non-spontaneity under the defined standard conditions—the adsorption in actual non-standard systems is effectively driven by prevailing gradients such as concentration differences.

Repeated cycle experiments for NH4+ and PO43–

-

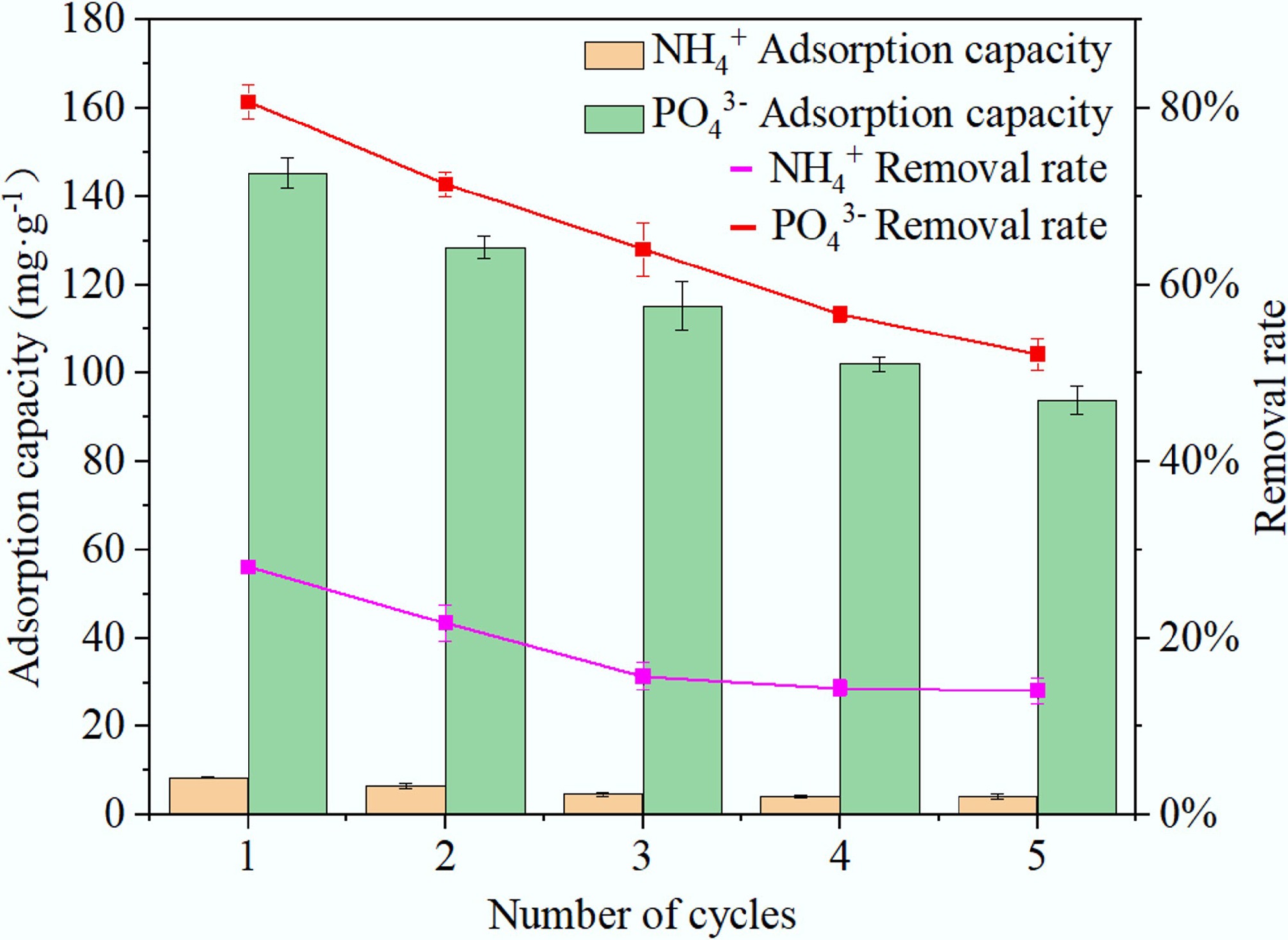

To evaluate the reusability of BC5-500, it underwent five cycles of experimental testing, with results shown in Fig. 11. The adsorption of NH4+ exhibited a rapid decline in removal efficiency during the first three cycles. However, upon continuing the adsorption cycles, the removal efficiency remained largely stable. In summary, after five adsorption-desorption cycles, the NH4+ adsorption capacity of BC5-500 dropped by 4.2 mg·g–1, with a corresponding 14% decrease in removal efficiency. For PO43– adsorption, the initial adsorption capacity and removal efficiency were 145.29 mg·g–1 and 80.72%, respectively. After five cycles, the adsorption capacity and removal efficiency decreased to 93.84 mg·g–1 and 52.13%, respectively. Despite this reduction, the material still maintained a high adsorption capacity and a removal efficiency exceeding 50%, demonstrating that BC5-500 possesses good reusability and practicality.

Figure 11.

Reusability of BC5-500 for the adsorption of NH4+ and PO43– over five consecutive cycles.

Removal efficiency of NH4+ and PO43– in actual swine wastewater

-

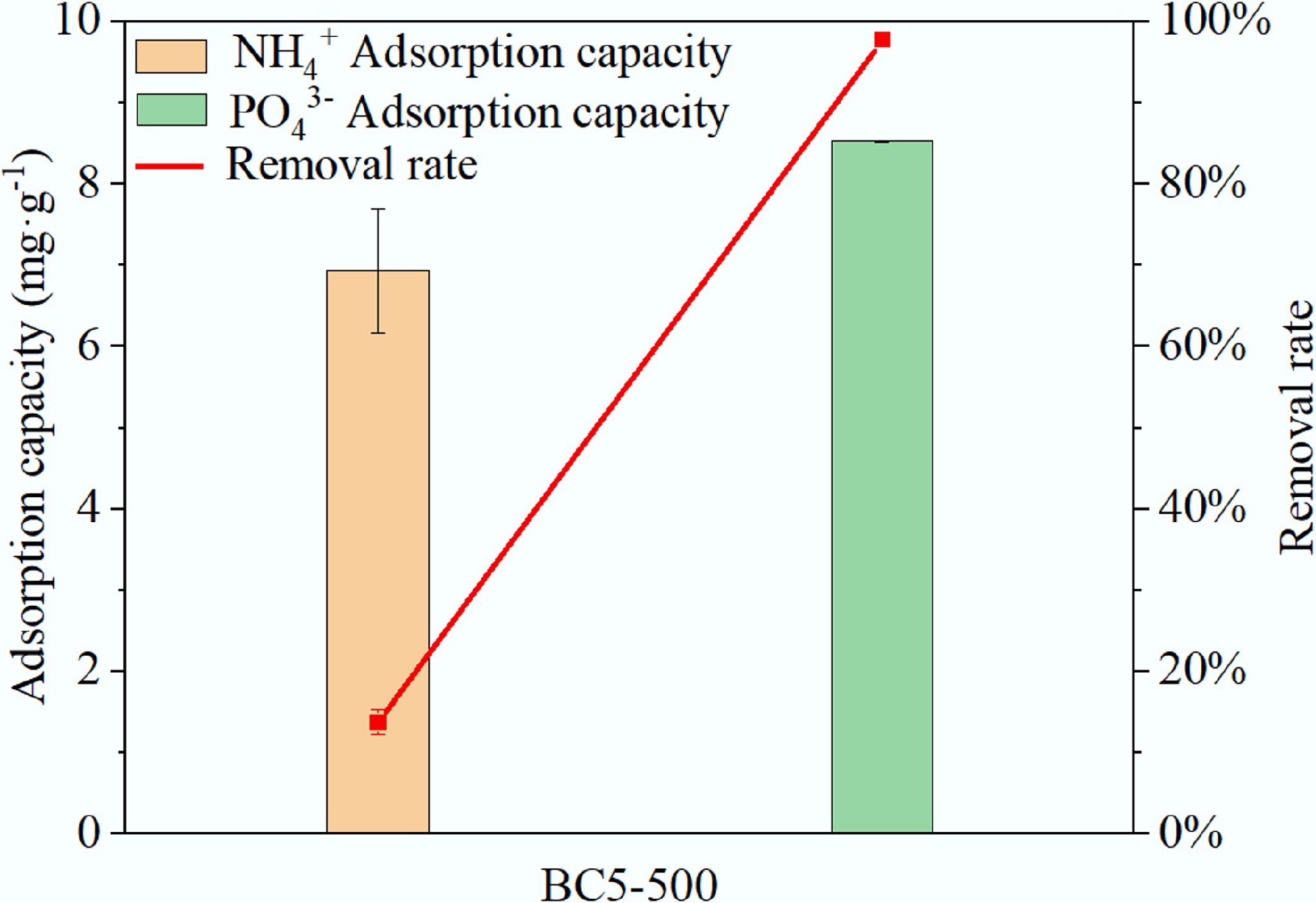

The swine wastewater was collected from a small-scale pig farm in Huangping County. After filtration, the wastewater had a pH of 7.48, with the following concentrations: NH4+ 84.00 mg·L–1, PO43– 14.54 mg·L–1, Cu(II) 0.58 mg·L–1, Cd(II) 0.15 mg·L–1, tetracycline (TCH) 7.01 mg·L−1, and oxytetracycline (OTC) 8.25 mg·L–1. Then, 30 mL of wastewater were combined with a 0.05 g sample of BC5-500 and shaken for 120 min for NH4+ adsorption and for 360 min for PO43– adsorption. Shaking was followed by filtering the liquid and measuring the remaining concentration.

As shown in Fig. 12, the adsorption capacities of BC5-500 for NH4+ and PO43– were 6.93 and 8.52 mg·g–1, respectively, with corresponding removal rates of 13.76% and 97.73%. The relatively low adsorption capacity for NH4+ in actual wastewater could be attributed to two main factors: first, the relatively low initial NH4+ concentration; second, the coexisting heavy metal ions and antibiotics likely compete with NH4+ for adsorption sites, thereby inhibiting its removal. The experimental results demonstrate that although BC5-500 shows limited NH4+ removal efficiency in complex aqueous matrices, its highly effective PO43– removal capacity can still significantly mitigate the environmental risks associated with phosphorus-rich wastewater[51]. Thus, BC5-500 represents a promising material for practical wastewater treatment applications.

Reaction mechanism

-

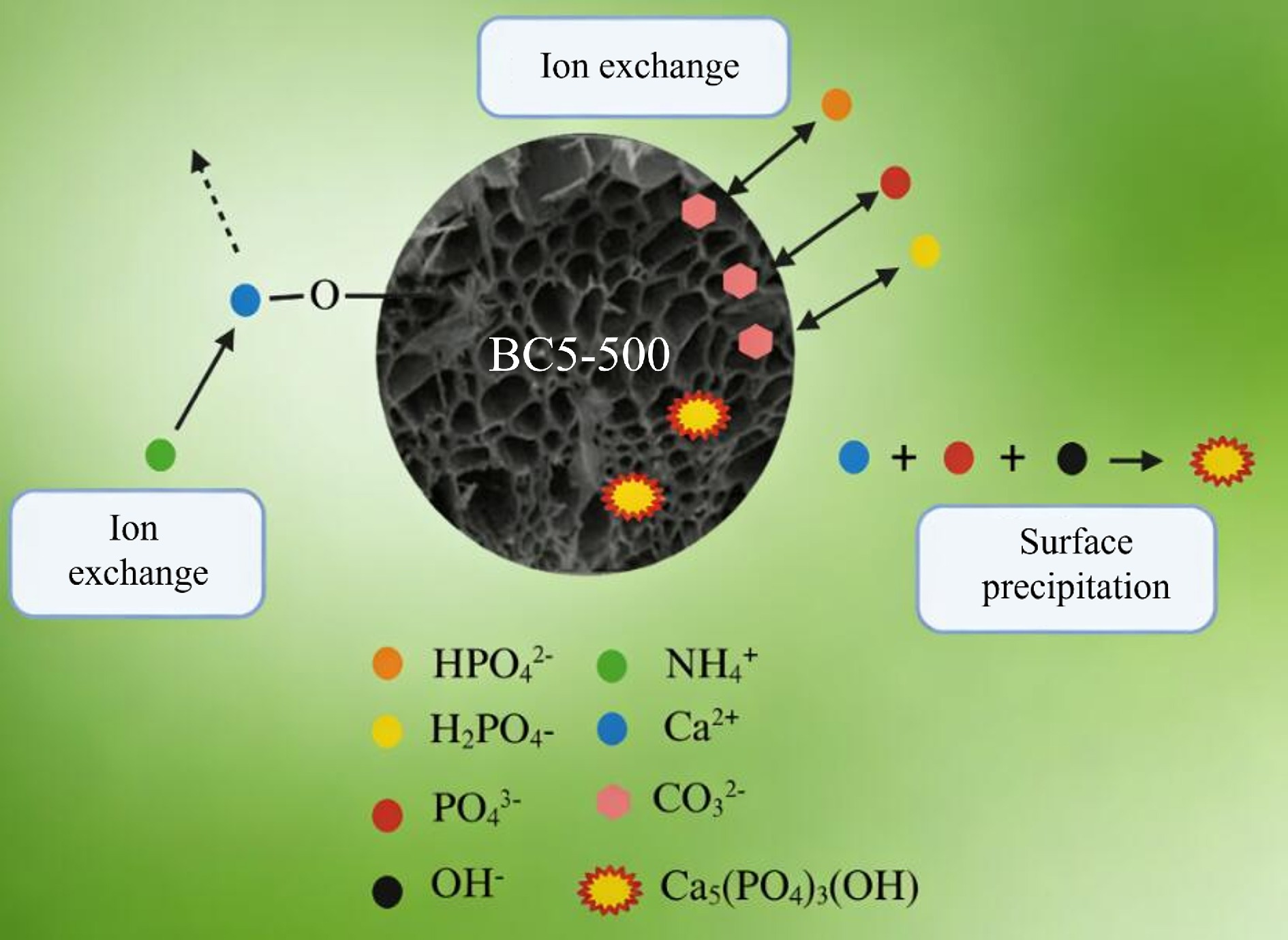

The N2 adsorption-desorption isotherm reveals that the modified material exhibits a Type IV isotherm and H1 hysteresis loop, indicating a mesoporous structure with relatively concentrated pore size distribution. The modified material exhibits increased SSA, pore volume, and average pore diameter. SEM analysis reveals a rougher surface with increased wrinkling and finer particles for BC5-500. This optimized porous structure enhances the adsorption of NH4+ and PO43–. The adsorption mechanism of BC5-500 for NH4+ and PO43– is illustrated in Fig. 13. XPS analysis indicates that the O–Ca structure content in BC5-500-N is lower than that in BC5-500, which is attributed to ion exchange between Ca2+ on BC5-500 and NH4+. FT-IR and XRD analyses indicate that the –OH groups on the BC5-500 surface react with phosphates in water to form Ca5(PO4)3(OH) precipitates, thereby adsorbing PO43–. XPS analysis of BC5-500 reveals a 19.82% decrease in O–C=O content, indicating that O–C=O groups participated in the adsorption reaction with PO43– and underwent ion exchange with H2PO4–, HPO42–, and PO43–.

-

This study successfully synthesized a porous biochar (designated BC5-500) through Ca(OH)2 modification of Camellia oleifera shells. For the simultaneous adsorption of NH4+ and PO43−, the material displays excellent performance, reaching maximum capacities of 15.44 and 172.04 mg·g−1. Alkaline conditions were favorable for NH4+ removal, whereas acidic conditions promoted PO43− adsorption. The adsorption kinetics for both pollutants followed the pseudo-second-order model. Isotherm analysis indicated that NH4+ adsorption involved both monolayer and multilayer processes, while PO43− adsorption was dominated by a multilayer mechanism. Mechanistic studies reveal that NH4+ removal occurs primarily via ion exchange, whereas PO43− removal was mainly governed by Ca–P precipitation, with additional contributions from surface functional group interactions. BC5-500 retained stable adsorption performance over five consecutive reuse cycles. In actual swine wastewater, the PO43− removal efficiency reached 97.73%, demonstrating its strong potential for practical application in the simultaneous recovery of nitrogen and phosphorus from wastewater.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/bchax-0026-0002.

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: Min Chen: writing – original draft, methodology, validation; Xichang Wu: conceptualization, software, visualization; Yu Wang: software, visualization; Jie Wang: visualization, supervision; Chaochan Li: conceptualization; Tianhua Yu: software, formal analysis; Anping Wang: resources, conceptualization, supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

This work is supported by the project of the Guizhou Provincial Department of Science and Technology (Grant Nos Qiankehe Zhicheng [2023] 078, Qiankehe Jichu-ZK [2024] zhongdian 055, and Qiankehe Pingtai-KXJZ [2025] 023), and Projects of Forestry Research in Guizhou Province (Grant No. GUI[2022] TSLY07).

-

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

-

Functionalized biochar was prepared from agricultural waste Camellia oleifera shells via chemical modification and pyrolysis.

The adsorption mechanisms and interaction patterns of NH4+ and PO43− on calcium hydroxide-modified biochar were further elucidated.

Utilizing Camellia oleifera shells to produce modified biochar for treating NH4+ and PO43− in water bodies achieves secondary utilization of agroforestry waste and resolves the disposal challenge of Camellia oleifera shell residues.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Min Chen, Xichang Wu

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article. - The supplementary files can be downloaded from here.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Chen M, Wu X, Wang Y, Wang J, Li C, et al. 2026. Ca(OH)2-modified Camellia oleifera shell biochar: preparation, characterization, and adsorption of NH4+ and PO43−. Biochar X 2: e005 doi: 10.48130/bchax-0026-0002

Ca(OH)2-modified Camellia oleifera shell biochar: preparation, characterization, and adsorption of NH4+ and PO43−

- Received: 04 December 2025

- Revised: 27 December 2025

- Accepted: 06 January 2026

- Published online: 30 January 2026

Abstract: Excessive nitrogen and phosphorus in aquatic systems trigger eutrophication and environmental contamination. Herein, Ca(OH)2-modified Camellia oleifera shell biochar was fabricated as an adsorbent for NH4+ and PO43− removal, with the effects of contact time, temperature, initial concentration, and pH on adsorption performance investigated, and the mechanisms clarified via kinetic/isothermal models combined with FT-IR and XPS characterizations. Results showed that NH4+ and PO43− adsorption both fit the pseudo-second-order kinetic model, indicating chemisorption dominance. NH4+ adsorption complied with both Langmuir and Freundlich models (monolayer-multilayer coexistence), while PO43− adsorption followed only the Freundlich model (predominant multilayer adsorption). Acidic conditions and low temperatures favored PO43− uptake, whereas alkaline conditions promoted NH4+ adsorption, with adsorption capacity showing a decrease-then-increase trend with temperature elevation. Notably, the modified biochar maintained favorable performance in complex swine wastewater. Mechanistically, NH4+ removal was dominated by ion exchange, while PO43− removal relied on the synergy of ion exchange and precipitation, with precipitation as the primary pathway. This work provides a cost-effective strategy for nutrient removal from wastewater via agricultural waste valorization.

-

Key words:

- Camellia oleifera shells /

- Modified biochar /

- NH4+ /

- PO43− /

- Adsorption mechanism