-

With advancements in science and technology, alongside improvements in living standards, mobile phones have become essential components of daily life. However, mobile phone batteries typically have a limited lifespan and generally necessitate replacement within a few years[1]. Moreover, as mobile phone technology continues to evolve, the frequency with which consumers upgrade their devices is also increasing, leading to a substantial accumulation of spent mobile phone batteries. Improper disposal of these batteries poses significant risks to the environment and human health, and also results in a considerable waste of metal resources[2].

Lignin is a complex natural polymer primarily composed of phenylpropane structural units, representing approximately 30% of the Earth's non-fossil organic carbon. It constitutes a significant by-product in both the papermaking industry and biorefinery processes, with an annual production volume ranging from 50–70 million tons[3]. Despite its abundance, less than 5% of lignin is currently valorized for the production of high-value commercial products such as adhesives, dispersants, and surfactants[4]. Alarmingly, over 90% of industrial lignin is either discarded as waste or incinerated as low-value fuel, leading to substantial resource wastage and environmental pollution[5].

Therefore, it is crucial to recycle spent mobile phone batteries and industrial lignin to not only mitigate pollution risks to the environment but also to reduce the demand for new resources, thereby promoting resource recycling and supporting sustainable development. If the synergistic resource recovery of these two types of solid wastes can be realized, their respective advantages can be fully leveraged, thereby achieving optimal resource allocation and maximizing resource utilization efficiency.

Sodium-ion batteries (SIBs) possess the potential to supplant lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) because of considerable advantages regarding resource abundance, safety, low temperature performance, rapid charging capabilities, and environmental friendliness[6]. As is well known, the anode material serves as a pivotal component in SIBs, with its performance exerting a direct influence on the overall efficacy of these energy storage systems[7]. Transition metal sulfides that operate via the transformation reaction mechanism have garnered significant research interest owing to their high theoretical specific capacity, excellent ionic transport properties, and superior mechanical and thermal stability. Notably, bimetallic sulfides demonstrate enhanced electrochemical performance relative to their single-metal counterparts, which can be credited to the synergistic effects arising from the interaction of dissimilar metal ions. Among the reported bimetallic sulfides, NiCo2S4 has been deliberately engineered and synthesized to serve as a potential anode material for SIBs. Nevertheless, pure NiCo2S4 presents certain limitations concerning cycle stability, volumetric changes, first-cycle Coulombic efficiency, kinetic performance, and cost-effectiveness[8]. Consequently, it is imperative to modify NiCo2S4 to enhance its sodium storage capabilities. And researchers often adopt a composite material design strategy that synergistically integrates NiCo2S4 with various carbon materials to bolster both structural integrity and electrochemical performance. For instance, Xi et al. prepared hollow mesoporous carbon spheres encapsulating NiCo2S4 nanoparticles, demonstrating superior rate performance and achieving a high capacity of 271 mAh g−1 at 10 A g−1[9]. However, the carbon sources are predominantly conventional industrial products, which do not fully align with the principle of 'treating waste with waste' in the context of deep resource recycling. To date, no studies have been reported on enhancing NiCo2S4's sodium storage performance through the combination of industrial lignin-derived carbon and NiCo2S4.

In this study, NiCo2S4 was synthesized from spent mobile phone batteries via a hydrothermal method, an approach characterized by straightforward operation, high product purity, controllable reaction parameters, and environmental sustainability[10]. The synthesized NiCo2S4 was carbonized in conjunction with lignin, resulting in the successful preparation of NiCo2S4/Co9S8@LC. This process enables the synergistic high-value utilization of both types of waste. Moreover, a series of characterizations was conducted to investigate the effect of Co9S8 and lignin-derived carbon on the structure, morphology, and sodium storage properties of NiCo2S4. This approach not only substantially lowers the synthesis cost of anode materials but also promotes the sustainable utilization of resources and environmental protection. Importantly, it offers a novel strategy for the recycling and reutilization of industrial lignin and spent LIBs.

-

The processes of discharging, disassembling, and dissolving spent mobile phone batteries (Nokia), along with the hydrothermal synthesis of NiCo2S4, have been detailed in a previous study[11].

Purification of industrial lignin

-

Two hundred g of industrial lignin (Jilin Papermaking (Group) Co., Ltd) was weighed and dissolved in NaOH solution with a pH ≥ 12 under continuous stirring for 2 h. Once the lignin was fully dissolved, the solution was filtered to remove insoluble impurities, and the filtrate was collected. Subsequently, while continuously stirring, 50% (w/w) sulfuric acid was slowly added to the filtrate to adjust the pH of the solution to 2. The mixture was stirred for an additional 2 h to allow lignin precipitation. The solution was then allowed to stand for 24 h, after which the precipitated lignin was collected by filtration. The collected lignin was washed thoroughly and subjected to freeze-drying to obtain purified lignin.

Synthesis of NiCo2S4/Co9S8@LC

-

A total of 0.2 g of NiCo2S4 was introduced into an ethanol-water mixture (Vethanol : Vwater = 1:4). The dispersion was subjected to multiple cycles of ultrasonic treatment to ensure homogeneity. Subsequently, lignin was introduced into a separate ethanol-water solution (Vethanol : Vwater = 1:4, C = 2 mg/mL) under ultrasonic conditions for thorough dispersion. The weight ratios of lignin to NiCo2S4 were set at 25%, 50%, and 75%. The two dispersions were then combined, and the pH of the final solution was regulated to 12 by incorporating a 20% (w/w) NaOH solution. The mixture was subjected to magnetic stirring at ambient temperature for a duration of 30 min, and then subjected to ultrasonic processing for another 30 min. This procedure was carried out repeatedly until a uniformly dispersed solution was obtained. Thereafter, the pH was lowered to 2 by adding a 50% (w/w) sulfuric acid solution. The solution was left undisturbed for 12 h to enable the full precipitation of NiCo2S4 and lignin. Finally, the NiCo2S4-lignin composite was collected via centrifugation and dried.

The above-mentioned synthesized NiCo2S4-lignin composites were dispersed in 50 mL of deionized water, and then K2CO3 was added as an activator at a K2CO3-to-lignin weight ratio of 1:1. The resulting mixture was continuously stirred for 4 h, subsequently dried at 80 °C, and finally ground into a fine powder for collection. Next, the sample was heated under a nitrogen atmosphere from ambient temperature to 250 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min and held at this temperature for 30 min. Subsequently, the temperature was further increased to 600 °C at the identical heating rate of 10 °C/min and maintained for 2 h to achieve complete carbonization of the lignin component. Afterward, the resulting product was thoroughly rinsed multiple times with deionized water and then dried at 100 °C to yield the final NiCo2S4/Co9S8@LC composite, which was designated as NCS/CS@LC25, NCS/CS@LC50, and NCS/CS@LC75, respectively.

Characterization of materials, electrochemical measurements, and computational details

-

The structural and morphological characterization techniques, the electrochemical performance evaluation procedures, and the theoretical calculation details for the synthesized samples were included in the Supplementary Material.

-

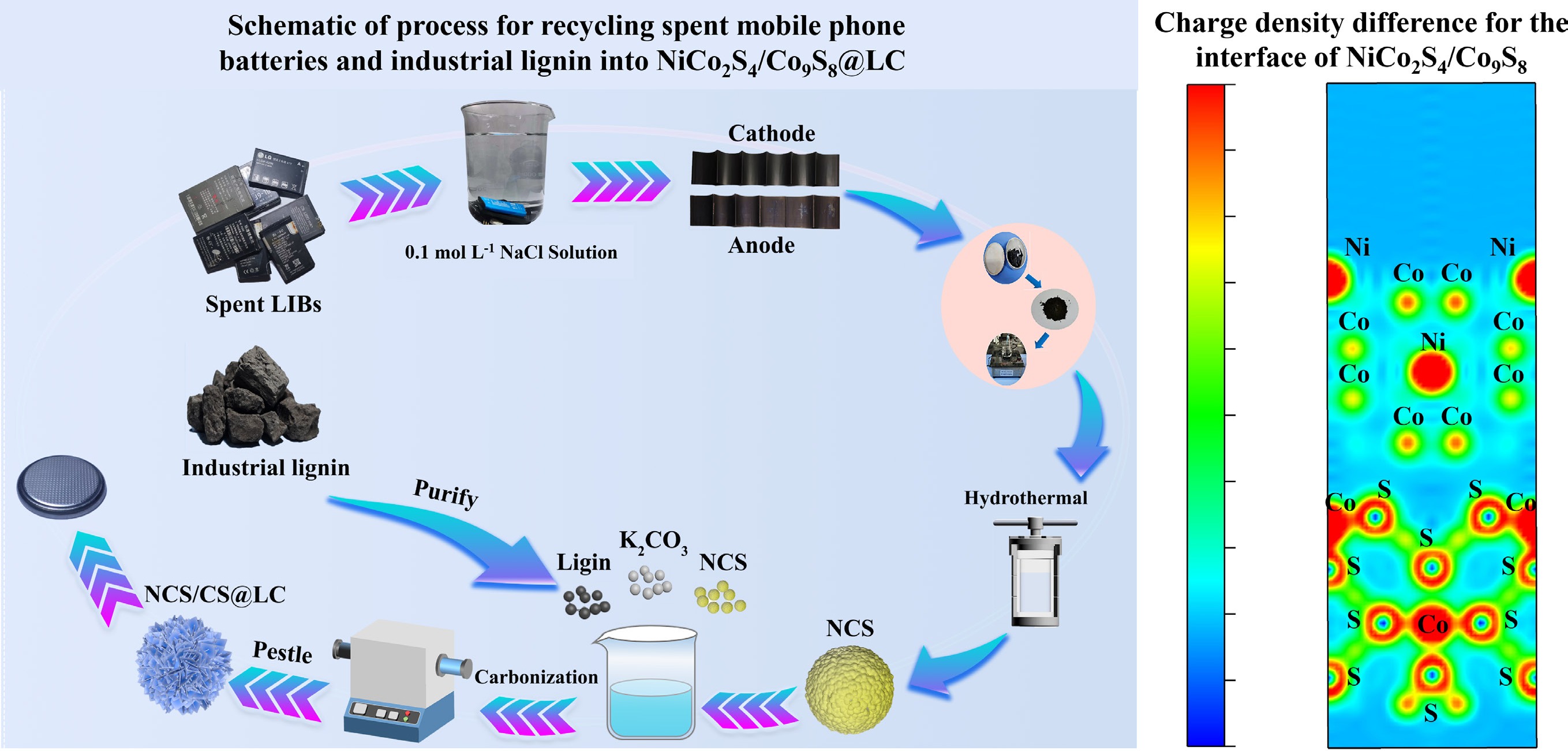

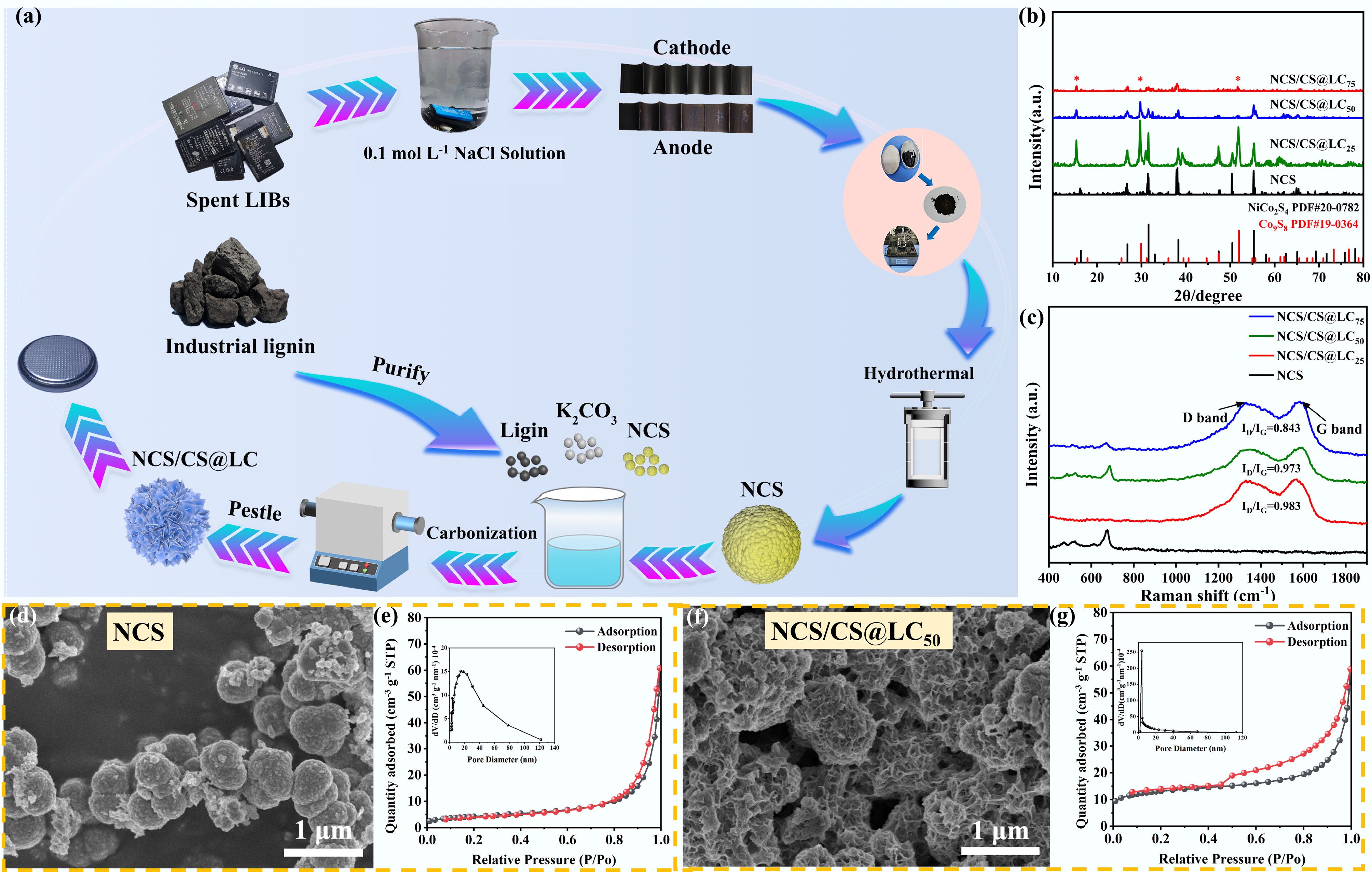

The flowchart illustrating the co-conversion process of spent mobile phone batteries and industrial lignin for the preparation of NCS/CS@LC is presented in Fig. 1a. The XRD patterns of the synthesized samples are presented in Fig. 1b. The observed diffraction peaks exhibited sharpness and high intensity, indicating a relatively complete crystal structure and elevated crystallinity. It was evident that the diffraction peaks of NCS aligned well with the standard card for NiCo2S4 (JCPDS No. 20-0782), confirming the successful synthesis of NiCo2S4. Upon incorporating varying amounts of lignin into NCS and subsequently carbonizing the composites in a nitrogen atmosphere, a new phase of Co9S8 (JCPDS No.19-0364) emerged, indicated by '*' in Fig. 1b. Notably, it appeared that NiCo2S4 may partially convert into Co9S8 due to the reorganization or recombination of metal ions from NiCo2S4 with sulfur ions present in the reaction system under conditions of elevated temperature and pressure, resulting in novel metal sulfide phase formation[12]. In addition, the sulfur-containing functional groups in lignin, such as methylthio groups, release S2− or H2S during thermal decomposition, thereby sustaining a sulfidation atmosphere. Concurrently, the decomposition produces reductive gases such as CO and H2, which lower the oxygen potential of the system and promote the generation of Co9S8. Ultimately, carbon materials derived from lignin may encapsulate these metal sulfides' surface to create a composite structure represented as NCS/CS@LC. The presence of other phases, such as NiCo2S4 and Co9S8, leads to notably weak and nearly undetectable diffraction peaks for carbon within the synthesized materials. This suggested that the carbon produced post-carbonization was amorphous in nature[13]. Nevertheless, the Raman spectrum corroborated the existence of carbon within NCS/CS@LC, as depicted in Fig. 1c.

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic of the process for recycling spent mobile phone batteries and industrial lignin into NiCo2S4/Co9S8@LC. (b) XRD patterns of synthesized samples. (c) Raman spectral analysis of synthesized samples. (d) SEM images of NCS. (e) Adsorption-desorption isotherm of NCS. (f) SEM images of NCS/CS@LC50. (g) Adsorption-desorption isotherm of NCS/CS@LC50.

Raman spectroscopy is a spectral analysis technique predicated on the Raman scattering effect, which elucidates molecular vibrational and rotational information of matter by examining the frequency difference between scattered and incident light. The G peak constitutes one of the most prominent characteristic peaks in carbon materials, primarily resulting from the stretching vibrations of sp2-hybridized carbon atoms[14]. Conversely, the D peak signifies another critical characteristic peak in carbon materials, predominantly arising from defects or disordered structures within the carbon atomic lattice[15]. As illustrated in Fig. 1c, it was evident that the typical D and G characteristic peaks were absent in NCS not co-carbonized with lignin; however, other samples exhibited significant D and G peaks located near 1,340 and 1,585 cm−1, respectively. These observations substantiated the presence of carbon within NCS/CS@LC. Furthermore, the intensity ratio of D and G peak (ID/IG) is frequently utilized as an essential parameter for characterizing defect density in carbon materials[16]. A progressive decrease in ID/IG from 0.983 to 0.843 was noted, suggesting a reduction in amorphous or defective carbon content alongside an enhancement in graphitization degree. However, an excessively high degree of graphitization may not be advantageous, as it leads to an increase in ordered graphite layers while reducing interlayer spacing, concurrently diminishing surface defects. This results in fewer Na+ adsorption sites, which could consequently impair the sodium storage capacity[17]. High levels of graphitization may yield a densely compacted carbon material detrimental to Na+ diffusion and storage capabilities, thereby adversely affecting cycling performance and Coulombic efficiency, as well as limiting Na+ diffusion rates that negatively impact rate performance[18]. Therefore, achieving an optimal ID/IG value is crucial for attaining superior electrochemical performance, which will be further substantiated through subsequent analyses.

Figure 1e, g, respectively, present the adsorption–desorption isotherms of NCS and NCS/CS@LC50, with the corresponding isotherms for the remaining samples provided in Supplementary Fig. S1, which were used to determine the specific surface area and pore size distribution. All four isotherms displayed typical type-IV characteristics, evident from the hysteresis loop observed in the high-pressure region, where the desorption curve lagged behind the adsorption curve during the desorption process. This phenomenon further confirmed that NCS and all the NCS/CS@LC samples possessed a mesoporous structure. The BJH model was employed to calculate the pore size distribution based on the Kelvin equation, considering the effects of capillary condensation on adsorption capacity. The results are displayed in the corresponding insets of Fig. 1e, g, and Supplementary Fig. S1. Additionally, the BET specific surface area and BJH pore size data are compiled in Table 1. It was evident that as the lignin weight ratio increased, the specific surface area initially decreased and subsequently increased, whereas the pore size exhibited a gradual decreasing trend. This trend could be attributed to the fact that varying amounts of lignin induce distinct cross-linking and condensation reactions during the carbonization process, thereby leading to diverse morphologies and pore structures in the resulting products. It is well established that an appropriate specific surface area can offer a greater number of active sites, facilitating the insertion and expulsion of Na+. An optimal pore structure facilitates electrolyte infiltration and ion mobility, leading to enhanced cycling durability and rate capability in SIBs. When both the specific surface area and pore dimensions are small, the availability of active sites for Na+-involved electrochemical reactions decreases, hindering Na+ migration and ultimately compromising the overall battery performance[19]. Conversely, if these parameters are excessively large, it may result in an increased occurrence of side reactions, which could significantly hinder the enhancement of electrochemical performance[20]. Subsequent studies demonstrated that NCS/CS@LC50 exhibited superior cycling and rate performance due to its optimal balance between specific surface and pore size. The morphology of the synthesized material is illustrated in Fig. 1d, f, and Supplementary Fig. S2. Pure NiCo2S4, which had not been co-carbonized with lignin, retained a spherical morphology, as previously reported[11]. Upon mixing NiCo2S4 and lignin in an ethanol-water solution at varying weight ratios and subjecting the mixture to drying and calcination, significant morphological changes occurred, resulting in the formation of a new phase denoted as Co9S8. The composite phase NiCo2S4/Co9S8 that formed was subsequently coated with carbon derived from lignin. It is evident that the weight ratio of lignin to NiCo2S4 exerts a substantial impact on the morphology. When the lignin content is insufficient, phase separation or structural reorganization may occur at the interface between NiCo2S4 and lignin during carbonization, leading to the agglomeration and stacking of product particles[21], as depicted in Supplementary Fig. S2a. Upon increasing the dosage of lignin, the carbonized lignin forms a continuous carbon skeleton structure and efficiently encapsulates the spherical metal sulfides, thereby exhibiting a honeycomb-like morphology as depicted in Fig. 1f. When an excessive amount of lignin is introduced, during the carbonization process, a series of complex chemical reactions, including pyrolysis, polycondensation, and catalytic cracking, may intensify between NiCo2S4 and lignin. These reactions significantly increase the specific surface area and result in structural collapse[22], as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S2b. Consequently, to achieve a honeycomb-like structure, it was optimal to utilize lignin at a weight ratio of 50%.

Table 1. The specific surface area, pore size, Warburg impedance factor (σ) and Na+ diffusion coefficient of the as-synthesized samples

Sample Specific surface area

(cm2 g−1)Pore size (nm) Warburg impedance

factor (σ)Na+ diffusion coefficient

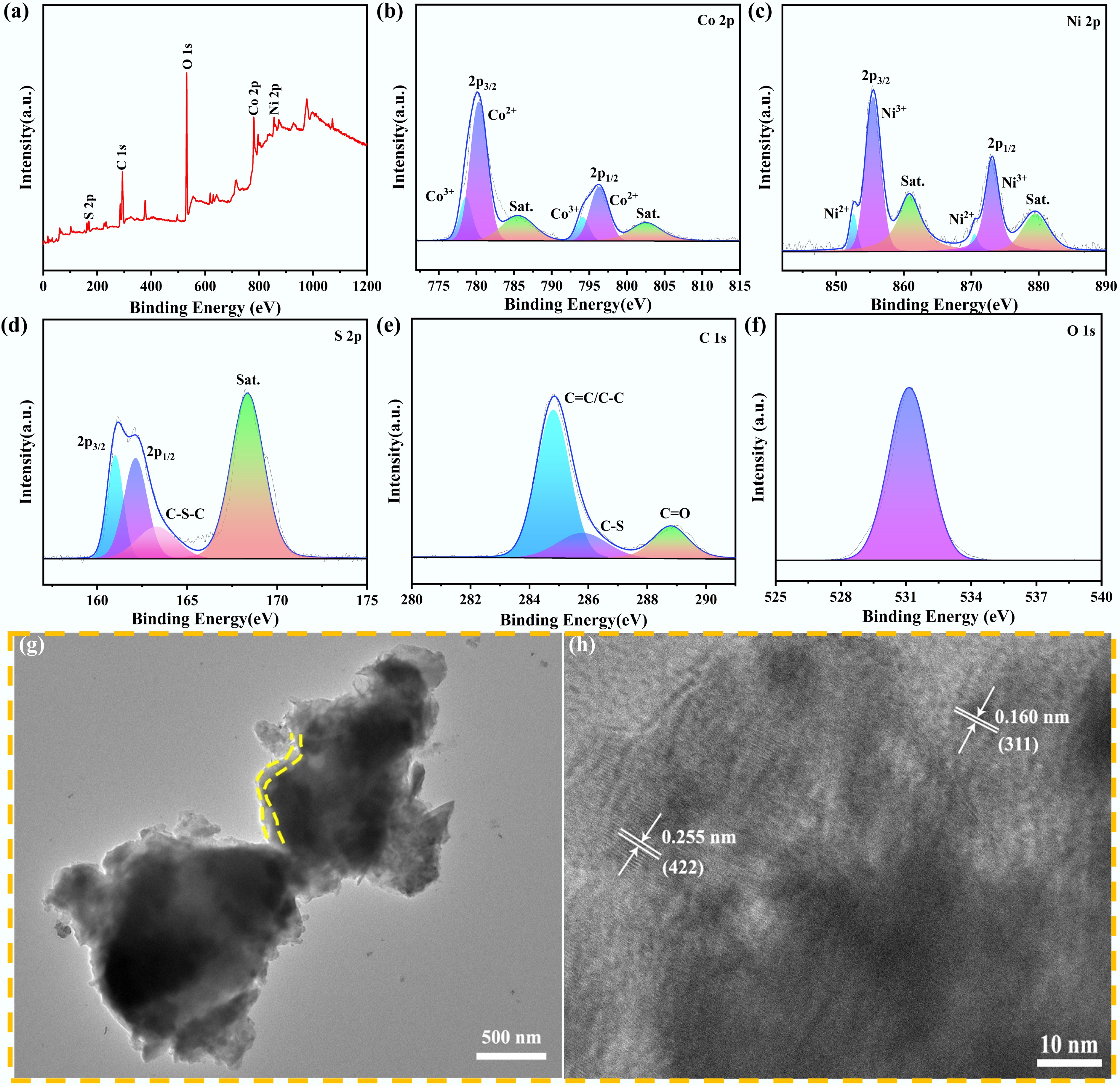

D (cm2 s−1)ICE (%) NCS 15.11 23.68 300.30 3.9 × 10−12 53.15 NCS/CS@LC25 6.03 23.54 82.90 5.1 × 10−11 54 NCS/CS@LC50 42.25 12.98 36.21 2.7 × 10−10 65.61 NCS/CS@LC75 95.20 10.02 133.50 2.0 × 10−11 46.77 The surface elemental composition of the NCS/CS@LC50 composite was comprehensively analyzed using XPS. As illustrated in Fig. 2a, the presence of elements such as Ni, Co, S, and C was confirmed. In Fig. 2b, the Co 2p spectrum exhibited spin-orbit splitting, typically manifested as two primary peaks at 780.11 and 796.22 eV, corresponding to Co 2p3/2 and Co 2p1/2, respectively. In addition to the primary peaks, satellite peaks (designated as Sat.), located at 785.50 and 802.50 eV, were also observed. By employing peak fitting techniques, the experimental data were deconvoluted into multiple independent peaks; specifically, those observed at 780.30 and 796.30 eV were attributed to Co2+ ions, while those detected at 778.60 and 794.10 eV corresponded to Co3+ ions, indicating that both oxidation states were present in this sample[23]. The XPS spectra of the Ni 2p orbitals exhibited two prominent peaks corresponding to 2p3/2 and 2p1/2, along with their respective satellite peaks observed at 860.85 and 879.50 eV, as displayed in Fig. 2c. The binding energy of the 2p3/2 peak was lower than that of the 2p1/2 peak, and its intensity was comparatively higher. Similarly, upon fitting these splits within the Ni 2p orbital, two additional peaks were identified at energies of 852.55 and 870.49 eV, which were associated with Ni2+. Conversely, two more distinct peaks were found at 855.45 and 873.10 eV, attributable to Ni3+, thus confirming that Ni exists in the +2 and +3 oxidation states within this sample[24]. The S 2p peak exhibited a spin-orbit splitting, resulting in two distinct sub-peaks, S 2p3/2 and S 2p1/2, located at binding energies of 160.99 and 162.13 eV, respectively. The excitation effect, commonly observed in metal sulfides, resulted in the formation of satellite peaks situated at 168.35 eV, as illustrated in Fig. 2d. The peak situated at 163.29 eV, which was assigned to the C–S–C bond, corroborated the formation of carbon derived from lignin and its binding to metal sulfides. In the C 1s spectrum (Fig. 2e), the peaks at 284.81, 285.80, and 288.80 eV corresponded to the C=C/C–C, C–S, and C=O bonds, respectively. Finally, the peak at 531.14 eV, exhibited in the O 1s spectrum (Fig. 2f), may have resulted from the oxidation of the carbon layer surface or the incorporation of oxygen during the preparation of the composite. Figure 2g presents the TEM image of NCS/CS@LC50, which is in good agreement with its SEM image, once again indicating its honeycomb-like morphology. Furthermore, the presence of carbon layers in NCS/CS@LC50 is illustrated in Fig. 2g, with some highlighted by yellow dotted lines. Figure 2h reveals the distinct lattice fringes of NCS/CS@LC50, further confirming its excellent crystallinity. Moreover, the plane spacings observed at 0.255 nm for NiCo2S4 (422) and at 0.160 nm for Co9S8 (311), as shown in Fig. 2h, illustrated the successful integration of NiCo2S4 and Co9S8 within the NCS/CS@LC50 sample.

Figure 2.

(a) XPS full spectrum and high-resolution XPS spectra of: (b) Co 2p, (c) Ni 2p, (d) S 2p, (e) C 1s, and (f) O 1s. (g) TEM image of NCS/CS@LC50. (h) Lattice fringes of NCS/CS@LC50.

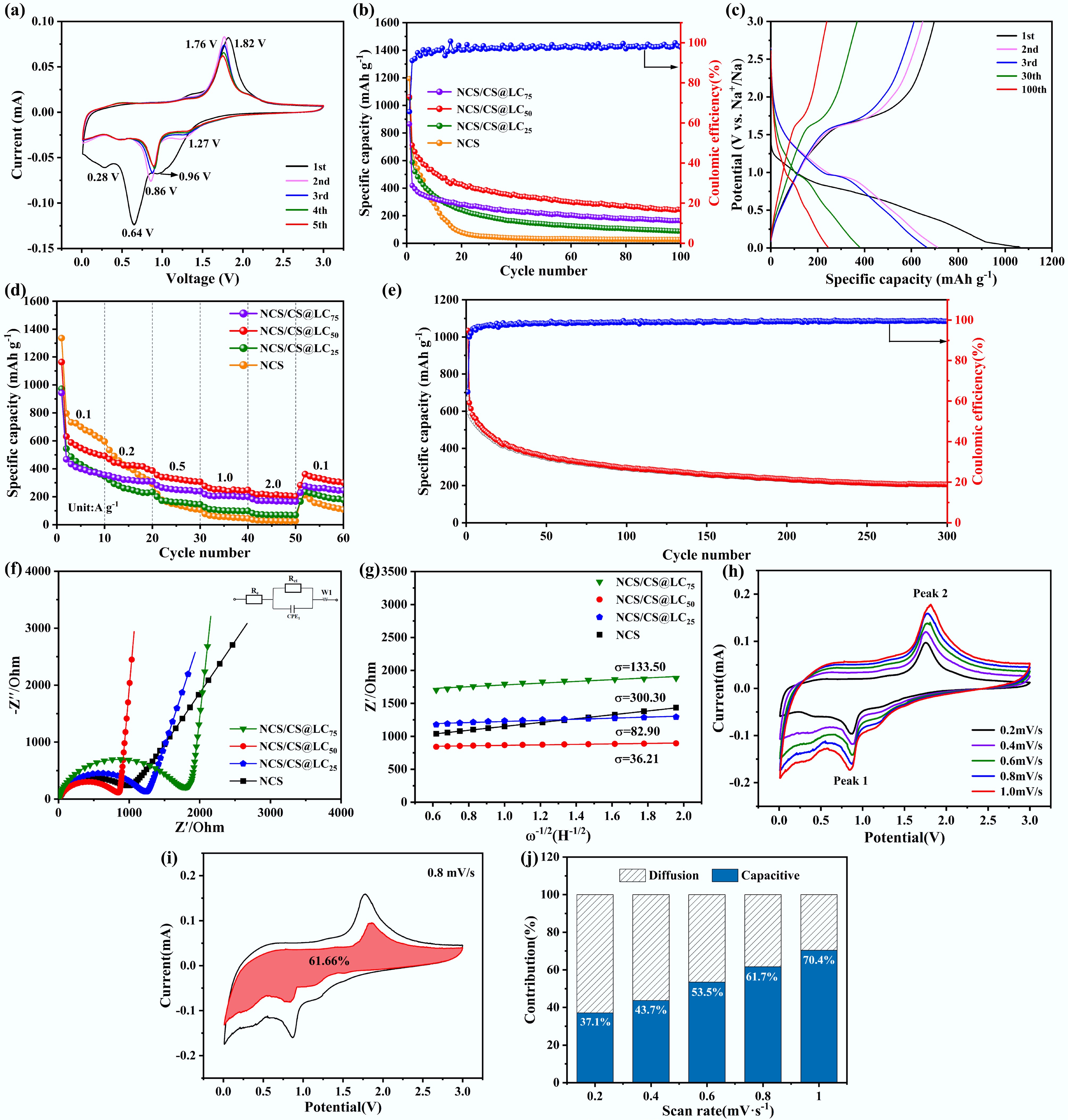

The synthesized material was coated onto a current collector copper foil, subsequently stamped, and assembled with sodium sheets to construct a sodium-ion half-cell for evaluating its electrochemical characteristics. Initially, the assembled sodium-ion half-cell underwent CV testing within a potential window of 0.01–3 V at a scan rate of 0.01 mV s−1. Figure 3a illustrates the CV curves for the initial five cycles of NCS/CS@LC50, while the CV plots for the other samples are provided in Supplementary Fig. S3. The CV curve revealed distinct oxidation and reduction peaks, indicating that NCS/CS@LC50 exhibited favorable electrochemical activity in SIBs. In the initial CV curve, the reduction peak at 0.96 V corresponded to the insertion of Na+ into NCS/CS@LC50, while reduction peaks at 0.64 and 0.28 V were associated with the reduction and deposition of electrolyte components on the surface of the negative electrode, leading to the formation of solid-electrolyte interphase (SEI) films, as well as the reduction of Co2+/Co3+ and Ni2+/Ni3+ to Co and Ni, respectively[25,26]. Correspondingly, the oxidation peak at 1.82 V was associated with the oxidation of Co and Ni to form CoSx and NiSx. In the subsequent CV plots, the reduction and oxidation peaks detected at 1.27, 0.86, and 1.76 V, respectively, correspond to the reduction and oxidation processes of Co2+/Co3+ and Ni2+/Ni3+. From the second cycle onward, the CV curves largely overlapped, indicating that NCS/CS@LC50 exhibited good reversibility[27]. Specifically, the insertion and extraction of Na+ in the electrode material were reversible, with no significant changes in electrode structure or loss of active sites. Moreover, it was observed that the integral area of the CV curve during the first cycle was greater than that of subsequent cycles, indicating that the initial cycle of the electrode experienced a substantial amount of charge transfer during charging and discharging, thereby reflecting a higher specific capacity compared to later cycles. This phenomenon was further corroborated by the galvanostatic charge-discharge profile presented in Fig. 3b, c. The discharge capacity of NCS/CS@LC50 was 1,062.8 mAh g−1 during the first cycle, which gradually decreased as cycling progressed. The other samples exhibited analogous variation trends, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S4. The underlying reasons for this decline were as follows. The active material on the surface of NCS/CS@LC50 may have reacted with the electrolyte to form an SEI layer, a process that consumed some of the active material[28]. As the charge-discharge cycles continued, the ongoing formation and reconfiguration of the SEI layer may have further depleted the active material, leading to a gradual decline in specific capacity. In contrast, the initial Coulombic efficiency of NCS/CS@LC50 was found to be superior to that of pure NCS, which is attributed to the incorporation of lignin-derived carbon layer. This carbon layer exhibits multiple synergistic effects, such as minimizing the irreversible consumption of SEI, mitigating the adsorption at defect sites, optimizing the arrangement of sodium storage active sites, enhancing conductivity, and strengthening the stability of the electrode-electrolyte interface[29]. Consequently, these effects collectively contributed to an enhancement in the initial Coulombic efficiency of NCS/CS@LC50. After 100 cycles, the specific capacities of NCS, NCS/CS@LC25, NCS/CS@LC50, and NCS/CS@LC75 were measured at 27.2, 87.5, 244.5, and 162.7 mAh g−1, respectively, as illustrated in Fig. 3b. The maximum specific capacity exhibited by NCS/CS@LC50 indicates that its specific surface area and pore dimensions have been precisely optimized, leading to improved electrical conductivity and structural stability as well as a reduced likelihood of side reactions. The initial Coulombic efficiency (ICE) serves as a key metric for assessing electrode reversibility and energy utilization efficiency. The calculated initial efficiencies of the synthesized samples are summarized in Table 1. Furthermore, as illustrated in Fig. 3c, the Coulombic efficiency of NCS/CS@LC50 increased rapidly after the initial cycle for two primary reasons. This calculation result indicates that an appropriate carbon coating thickness can maximize the ICE by synergistically optimizing ion and electron transport, suppressing side reactions, and mitigating volume expansion. However, a coating that is either too thin or too thick will lead to reduced ICE. First, NCS/CS@LC50 may demonstrate good structural stability during charging and discharging, which helps to minimize the shedding of active materials and the decomposition of the electrolyte, thereby enhancing Coulombic efficiency[30]. Second, as the charge-discharge cycles progressed, the SEI membrane gradually stabilized, reducing electrolyte consumption and active material loss. Consequently, the Coulombic efficiency experienced a rapid increase from the second cycle onward.

Figure 3.

(a) CV plot of first five cycles for NCS/CS@LC50. (b) Constant current charge-discharge profile of NCS/CS@LC50 at a current of 0.1 A g−1. (c) Capacity-voltage curve of NCS/CS@LC50 for 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 30th, and 100th. (d) Rate performance plot of NCS/CS@LC50 at various current densities (0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, and 0.1 A g−1). (e) Cycling performance of NCS/CS@LC50 at a current density of 0.5 A g−1. (f) Nyquist diagram of synthesized NCS and NCS/CS@LC, accompanied by an equivalent circuit diagram as its illustration. (g) Straight line fitted between Z' and ω−1/2 at low frequencies for synthesized NCS and NCS/CS@LC. (h) CV measurements of NCS/CS@LC50 electrode conducted at varying scan rates. (i) Pseudocapacitive contribution of NCS/CS@LC50 electrode evaluated at a scan rate of 0.8 mV s−1. (j) Ratio of pseudocapacitance control to diffusion control for NCS/CS@LC50 electrode at varying sweep rates.

Figure 3d illustrates the rate performance of NCS/CS@LC50, which outperformed all other samples. At current densities of 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, and 2 A g−1, the average discharge specific capacities were measured at 548.2, 423.3, 328.1, 247.1, and 208.7 mAh g−1, respectively. Upon decreasing the current density to 0.1 A g−1, the specific capacity was restored to 332.2 mAh g−1, rather than the initial 548.2 mAh g−1. The irreversible capacity loss may be attributed to lattice stress in electrode materials under high-rate operation, intensified interfacial side reactions, increased polarization, and the shedding or dissolution of active materials. Under high current charge and discharge conditions, the transport of Na+ and electrons within the anode material may have been constrained, leading to some active substances being unable to participate in electrochemical reactions promptly[31]. Additionally, the anode material may have undergone significant volume changes or structural stresses. Moreover, it is essential for the anode material to possess rapid kinetic response capabilities to facilitate swift electrochemical reactions[32]. Consequently, as the current increased, the specific capacity tended to decrease. When the current was reduced, a rapid kinetic response from the anode material allowed for the recovery of specific capacity. This observation indicated that NCS/CS@LC50 had effective ion and electron transport pathways capable of supporting rapid electrochemical reactions. NCS/CS@LC50 could also maintain good structural stability after undergoing high-current charging and discharging cycles without severe structural damage or performance degradation. Furthermore, NCS/CS@LC50 demonstrated commendable kinetic properties and stable electrochemical activity across varying current conditions. Overall, the aforementioned phenomena and analysis indicated that NCS/CS@LC50 exhibited favorable ion and electron transport properties, exceptional structural stability, and promising kinetic characteristics. The long-term cycling performance of anode materials for sodium-ion batteries is a key indicator for assessing their practical applicability for Fig. 3e. It fundamentally reflects the material's ability to withstand structural degradation, accumulation of side reactions, and interfacial deterioration during repeated Na+ intercalation and deintercalation processes. As shown in Fig. 3e, NCS/CS@LC50 exhibited stable cycling performance, retaining a specific capacity of 207 mAh g−1 after 300 cycles at a current density of 0.5 A g−1, which demonstrates its excellent cycle stability. This favorable performance is attributed to the optimal thickness of the lignin-derived carbon coating, which effectively mitigates volume stress and suppresses metal ion dissolution. Furthermore, the SEM image of NCS/CS@LC50 after 300 cycles revealed that its hollow mesoporous structure remained well-preserved, further confirming its excellent cycling stability (Supplementary Fig. S5).

AC impedance analysis is frequently utilized to elucidate the internal impedance characteristics of batteries and assess the reaction kinetics of the electrodes, playing a crucial role in battery research. AC impedance measurements were performed using an electrochemical workstation across a frequency range of 100 kHz to 0.01 Hz at ambient temperature, resulting in the acquisition of Nyquist plots (Fig. 3f). Each Nyquist plot exhibited a semicircle in the high-frequency range and a straight line in the low-frequency range. The semicircle in the high-frequency range primarily represented the charge transfer impedance (Rct) at the electrode/electrolyte interface. During battery charging and discharging, charge must be transferred between the electrodes and the electrolyte, with the impedance of this process reflected in the high-frequency range[33]. The low-frequency range primarily reflected the diffusion process of ions within solid materials. In battery systems, ions must diffuse through solid electrode materials to participate in electrochemical reactions. The impedance associated with this process, referred to as Warburg impedance (Zw), is typically manifested in the low-frequency range as a diagonal line[34]. Furthermore, the intercept of the Z'-axis in the high-frequency range is regarded as the electrolyte impedance (Re)[35]. The EIS spectra were meticulously analyzed using an equivalent circuit model with the aid of Zview software. The Rct values of NCS, NCS/CS@LC25, NCS/CS@LC50, and NCS/CS@LC75 were 855.3, 1,144.0, 790.3, and 1,651.0 Ω, respectively. The results indicated that the Rct of NCS/CS@LC50 was the lowest, attributable to three key factors. First, the regular and uniform honeycomb-like structure of NCS/CS@LC50 facilitated a shorter diffusion path for ions, thereby reducing the Rct. Second, the synergistic interaction between NiCo2S4 and Co9S8 may also have contributed to lowering the Rct and enhancing its electrochemical performance. Third, the formation of lignin-derived carbon increased the conductivity of the material, which accelerated interfacial charge transfer and further diminished the Rct[36]. This minimized energy loss during the transmission process, thereby allowing the SIBs to demonstrate superior electrochemical performance during both charging and discharging. Building upon this, the EIS data were utilized along with Eqs (1) and (2) to calculate the Na+ diffusion coefficient (D)[37]. Initially, the Warburg coefficient (σ) was determined through linear fitting of Z' and ω−1/2, as illustrated in Fig. 3g. Subsequently, D was computed using Eq. (1), and the results are presented in Table 1. As anticipated, the D of NCS/CS@LC50 was found to be highest, indicating that Na+ could be embedded into and detached from NCS/CS@LC50 most rapidly, thereby further validating the optimal rate performance and minimal charge transfer resistance of NCS/CS@LC50.

$ \mathrm{D=R}^{ \mathrm{2}} \mathrm{T}^{ \mathrm{2}} \mathrm{/2A}^{ \mathrm{2}} \mathrm{n}^{ \mathrm{4}} \mathrm{F}^{ \mathrm{4}} \mathrm{C}^{ \mathrm{2}} \mathrm{\sigma }^{ \mathrm{2}} $ (1) $ \mathrm{Z'=R}_{ \mathrm{e}} + \mathrm{R}_{ \mathrm{ct}} +\mathrm{\sigma \omega }^{ \mathrm{-1/2}} $ (2) To thoroughly assess the pseudocapacitive characteristics of NCS/CS@LC50 and quantify the contribution of pseudocapacitance, CV measurements were performed at various scan rates of 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1 mV s−1, with results presented in Fig. 3h. It was clear that as the sweep rate increased, the peak current also rose correspondingly. According to the Randles-Sevcik equation, there exists a linear correlation between the square root of the peak current and the sweep velocity, which accounts for this observed phenomenon. Furthermore, as the scan rate increased, both the oxidation and reduction peak potentials exhibited shifts; specifically, the oxidation peak shifted towards more positive potentials while the reduction peak moved towards more negative potentials. This phenomenon was attributed to the fact that, for oxidation reactions, the concentration of electrons at the electrode surface decreases with increasing scan rate, as electrons are transferred more rapidly to the solution. To sustain the reaction, a higher electric potential is necessary to facilitate electron transfer; consequently, the oxidation peak potential shifts towards more positive values[16]. Conversely, in reduction reactions, the concentration of electrons at the electrode surface increases with rising scanning rates because electrons are transferred from the solution to the electrode more swiftly. In this scenario, a lower potential suffices to drive electron transfer, resulting in a shift of the reduction peak potential towards more negative values[38].

Additionally, the b-value was utilized to identify the charge storage mechanism of NCS/CS@LC50 throughout its charge and discharge cycles. First, the relationship between peak current (i) and sweep velocity (v), expressed as i = avb, was transformed into a logarithmic form: log(i) = b × log(v) + log(a). Subsequently, by performing a linear fit on log(i) and log(v), the value of b was determined and is presented in Supplementary Fig. S6; this was because b represented the slope of the fitted line. It is well-known that a b-value of 0.5 indicates battery-like behavior in the electrode material, with the corresponding process being governed by diffusion control. If the b-value is between 0.5 and 1, the electrode material displays characteristics of both battery and pseudocapacitance properties. When the b-value exceeds 1, it signifies that the electrode material primarily demonstrates pseudocapacitive behavior[39]. Supplementary Fig. S6 clearly shows that the b-value was 0.65 for the reduction peak and 0.58 for the oxidation peak. This indicated that charge storage and release occurred through both ion diffusion within NCS/CS@LC50 (cell behavior) and Faradaic processes at or within the electrode surface (pseudocapacitance behavior). These mechanisms contribute to enhancing the energy density, power density, and cycling stability of SIBs.

Furthermore, the pseudocapacitance contribution ratio was calculated. For each specific voltage value, k1 and k2 values were obtained by fitting i/v1/2 and v1/2 at different sweep rates using Eq. (4), which is mathematically derived from Eq. (3)[40]:

$ \mathrm{i=k}_{ \mathrm{1}} \mathrm{v+k}_{ \mathrm{2}} \mathrm{v}^{ \mathrm{1/2}} $ (3) $ \mathrm{i/v}^{ \mathrm{1/2}} \mathrm{=k}_{ \mathrm{1}} \mathrm{v}^{ \mathrm{1/2}}+ \mathrm{k}_{ \mathrm{2}} $ (4) where, i stands for current, v represents scan rate, and k1 and k2 are the fitting parameters.

Based on the k1 value obtained through fitting and the specific voltage value, as well as the sweep rate v, the current value contributed by the pseudocapacitor was calculated from icap = k1v. Then, using the voltage as the abscissa and the icap as the ordinate, the curve of the pseudocapacitance was plotted. Next, area fitting of the pseudocapacitance curve was performed to determine its contribution rate. The fitted pseudocapacitance curve was then compared with the original CV curve, allowing us to analyze the contribution of pseudocapacitive behavior to the total current[41]. The results are presented in Fig. 3i, j. As illustrated in Fig. 3i, pseudocapacitive behavior accounted for 61.66% of the total current at a sweep speed of 0.8 mV s−1. Additionally, it was evident from Fig. 3j that the contribution rate of pseudocapacitance increased with higher sweep rates. A high contribution rate enabled charge to be rapidly stored and released on or near the surface area of NCS/CS@LC50, enhancing both charge-discharge rates and energy output for the battery while improving cycle stability[42]; this allowed Na+ to embed and detach more rapidly, thereby boosting the battery's rate performance.

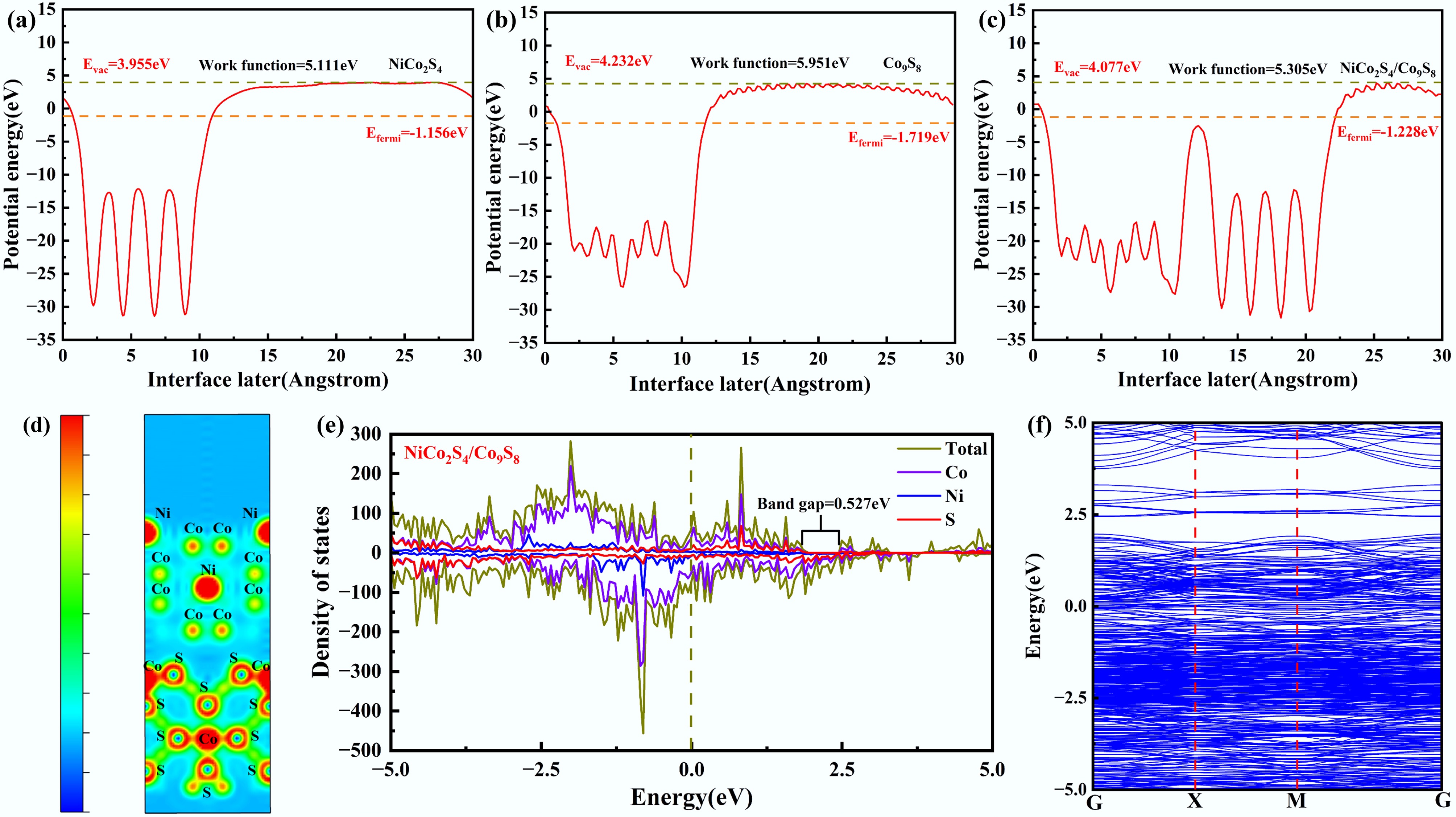

To elucidate the impact of the newly formed Co9S8 phase on the electrochemical performance of NiCo2S4 at the microstructural level, systematic calculations and analyses of electronic interactions at the NiCo2S4/Co9S8 interface were conducted using density functional theory (DFT). As illustrated in Fig. 4a and b, the Fermi level of NiCo2S4 was calculated to be −1.156 eV, which was marginally higher than that of Co9S8 (−1.719 eV). This subtle difference in energy levels exerts a notable influence when the two materials form a heterojunction[43]. Once the generated Co9S8 is coated onto NiCo2S4, a contact potential difference forms at the interface, facilitating electron transfer from the inner NiCo2S4 to the outer Co9S8. From the standpoint of electronic work function analysis, the NiCo2S4/Co9S8 heterostructure exhibited a work function of 5.305 eV (as depicted in Fig. 4c), which was intermediate between those of pure NiCo2S4 (5.111 eV) and pure Co9S8 (5.951 eV). This observation suggests that the electromotive force of NiCo2S4/Co9S8 is predominantly governed by Co9S8, highlighting the critical influence of Co9S8 in determining the overall electrochemical performance of NiCo2S4/Co9S8[43]. Figure 4d presents the charge density difference for the interface of NiCo2S4/Co9S8, showing that sulfur atoms located in the shell layer donate electrons, whereas cobalt atoms supply holes, thereby establishing a charge transfer pathway. Furthermore, these shell-layer sulfur atoms engage in additional charge transfer pathways with both nickel and cobalt atoms situated in the core layer. The density of states (DOS) and band structure of NiCo2S4/Co9S8 were computed to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of its intrinsic electronic properties. The band structure presented in Fig. 4f aligns well with the corresponding DOS profile (Fig. 4e), as regions exhibiting pronounced DOS peaks correspond to densely populated segments of the band structure[44]. The electronic states near the Fermi level predominantly arise from Ni-3d, Co-2p, and S-2p orbitals. The elevated DOS near the Fermi level of NiCo2S4/Co9S8 suggests that this composite exhibits superior electrical conductivity[45]. Combined with the favorable conductive properties of lignin-derived carbon, this feature contributes to the enhanced sodium storage performance of NiCo2S4/Co9S8@LC. The bandgap configuration (0.527 eV), as shown in Fig. 4e, is sufficiently wide to prevent the reduction of open-circuit voltage that typically arises from an excessively narrow bandgap. The relatively wide bandgap contributes to mitigating energy losses associated with non-radiative recombination during electrochemical processes, thereby enhancing the overall energy conversion efficiency[43]. Thus, DFT-based theoretical calculations reveal that NiCo2S4/Co9S8@LC possesses superior electronic transport properties and low charge transfer resistance, endowing it with significant potential as an anode material for SIBs.

Figure 4.

Calculated work function of (a) NiCo2S4, (b) Co9S8, and (c) NiCo2S4/Co9S8. (d) Charge density difference for the interface of NiCo2S4/Co9S8. (e) Density of state, and (f) band structure for NiCo2S4/Co9S8.

Ultimately, the sodium storage performance of NCS/CS@LC50 synthesized from spent mobile phone batteries and modified with lignin-derived carbon was evaluated against previously reported data (Table 2). The results demonstrated that its electrochemical performance is comparable or slightly inferior to that of previously reported NiCo2S4 prepared by analytic reagents. However, this study successfully achieved the high-value utilization of waste resources. The resulting material, NCS/CS@LC50, exhibits excellent sodium storage performance while being derived from sustainable and environmentally benign feedstocks, demonstrating its significant potential for industrial application. This approach not only substantially reduces the manufacturing cost and enhances the market competitiveness of SIBs but also facilitates their large-scale deployment in smart grids, electric vehicles, and various electronic devices.

Table 2. Comparison of the electrochemical performance of the synthesized NCS/CS@LC50 in this study with that of NiCo2S4 reported in the literature

-

In this research, NCS/CS@LC50 was prepared via a hydrothermal process utilizing spent mobile phone batteries and industrial lignin as the primary raw materials. The composite integrated the high electrochemical activity of NiCo2S4 and Co9S8 with the excellent electrical conductivity of carbon materials, presenting unique structural and performance advantages. Electrochemical testing revealed that the NCS/CS@LC50 demonstrated high reversible specific capacity, good cycling stability, and exceptional rate performance. These enhancements in performance were primarily attributed to the synergistic effects of its various components and the distinctive structure of this composite. Specifically, NiCo2S4 and Co9S8 provided a rich array of redox reaction sites, facilitating the Na+ intercalation/deintercalation; additionally, the incorporation of carbon materials enhanced overall electrode conductivity, promoting rapid electron transport. Furthermore, this study considered the effect of lignin-derived carbon on the morphology of NCS/CS@LC, providing valuable references for further optimizing the performance of composite materials. Simultaneously, the feasibility of utilizing spent mobile phone batteries and industrial lignin as raw materials to prepare high-performance sodium storage materials was also validated, providing a new perspective on the resource utilization of spent batteries and industrial lignin.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/bchax-0026-0005.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Changwei Dun: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, formal analysis, writing − original draft, funding acquisition, resources, writing − review and editing; Yizhao Zhao: investigation, methodology, data curation; Pengpeng Zhang: conceptualization, investigation, formal analysis, data curation; Hua Lv: conceptualization, resources; Yumin Li: methodology, supervision; Yuebin Xi: funding acquisition, supervision, methodology, formal analysis, writing − review and editing; Xijun Zhang: resources, conceptualization, investigation; Rui Liang: conceptualization, supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

-

This research was supported by the Postdoctoral Research Funds from Henan Province (Grant No. 5101039470652); collaborative scientific research projects with Henan Nuofei Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Grant Nos 5201039160188 and 5201039160224); National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22108135); Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (Grant Nos ZR2024MB12 and ZR2020QB197); Shandong University youth innovation team (Grant No. 2023KJ137).

-

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

-

This study offers a novel strategy for the recycling of industrial lignin and spent LIBs.

This approach significantly reduces the synthesis cost of anode materials.

The co-recycled product NCS/CS@LC50 demonstrates superior sodium storage performance.

Co9S8 and lignin-derived carbon exert a pronounced enhancing effect on the sodium storage.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Changwei Dun, Yizhao Zhao

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article. - The supplementary files can be downloaded from here.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Dun C, Zhao Y, Zhang P, Lv H, Liu Y, et al. 2026. Synergistic conversion of spent mobile phone batteries and industrial lignin into the NiCo2S4/Co9S8@LC composite with enhanced sodium storage performance. Biochar X 2: e007 doi: 10.48130/bchax-0026-0005

Synergistic conversion of spent mobile phone batteries and industrial lignin into the NiCo2S4/Co9S8@LC composite with enhanced sodium storage performance

- Received: 21 November 2025

- Revised: 31 December 2025

- Accepted: 13 January 2026

- Published online: 10 February 2026

Abstract: This study systematically investigated the NiCo2S4/Co9S8@LC composite synthesized from spent mobile phone batteries and industrial lignin, focusing on its sodium storage characteristics. A hydrothermal method was employed to successfully fabricate NCS/CS@LC50, exhibiting a honeycomb-like morphology through the precise control of lignin content. This composite integrated the high electrochemical activity of NiCo2S4 and Co9S8 with the superior conductivity of carbon materials, demonstrating promising sodium storage performance. The results indicated that NCS/CS@LC50 exhibited a high specific discharge capacity, i.e., an initial discharge specific capacity of 1,062.8 mAh g−1, and outstanding cycling stability. The unique architecture of NCS/CS@LC50 facilitated the effective insertion and extraction of Na+, allowing the material to preserve its structural stability throughout repeated charge-discharge processes, which in turn greatly improved the battery's cycling performance. At elevated current densities, such as 2.0 A g−1, NCS/CS@LC50 continued to exhibit a high specific discharge capacity (208.7 mAh g−1), demonstrating excellent rate performance. This research introduces an innovative approach to effectively recycle and reuse spent mobile phone batteries and industrial lignin, while also providing new insights into the design of electrode materials for sodium-ion batteries.

-

Key words:

- Spent batteries /

- Industrial lignin /

- NiCo2S4/Co9S8@LC /

- Biochar /

- Sodium storage