-

As a resilient carbohydrate source, cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz), a root crop, demonstrates pantropical adaptation, maintaining significant cultivation footprints across equatorial agriculture systems in Sub-Saharan Africa, South/Southeast Asian farmlands, and Meso-American agroecozones. It is cultivated in over 105 countries and serves as a staple food for nearly one billion people worldwide[1,2]. The frequent occurrence of diseases has caused a serious decline in quality due to long-term continuous monocropping of cassava.

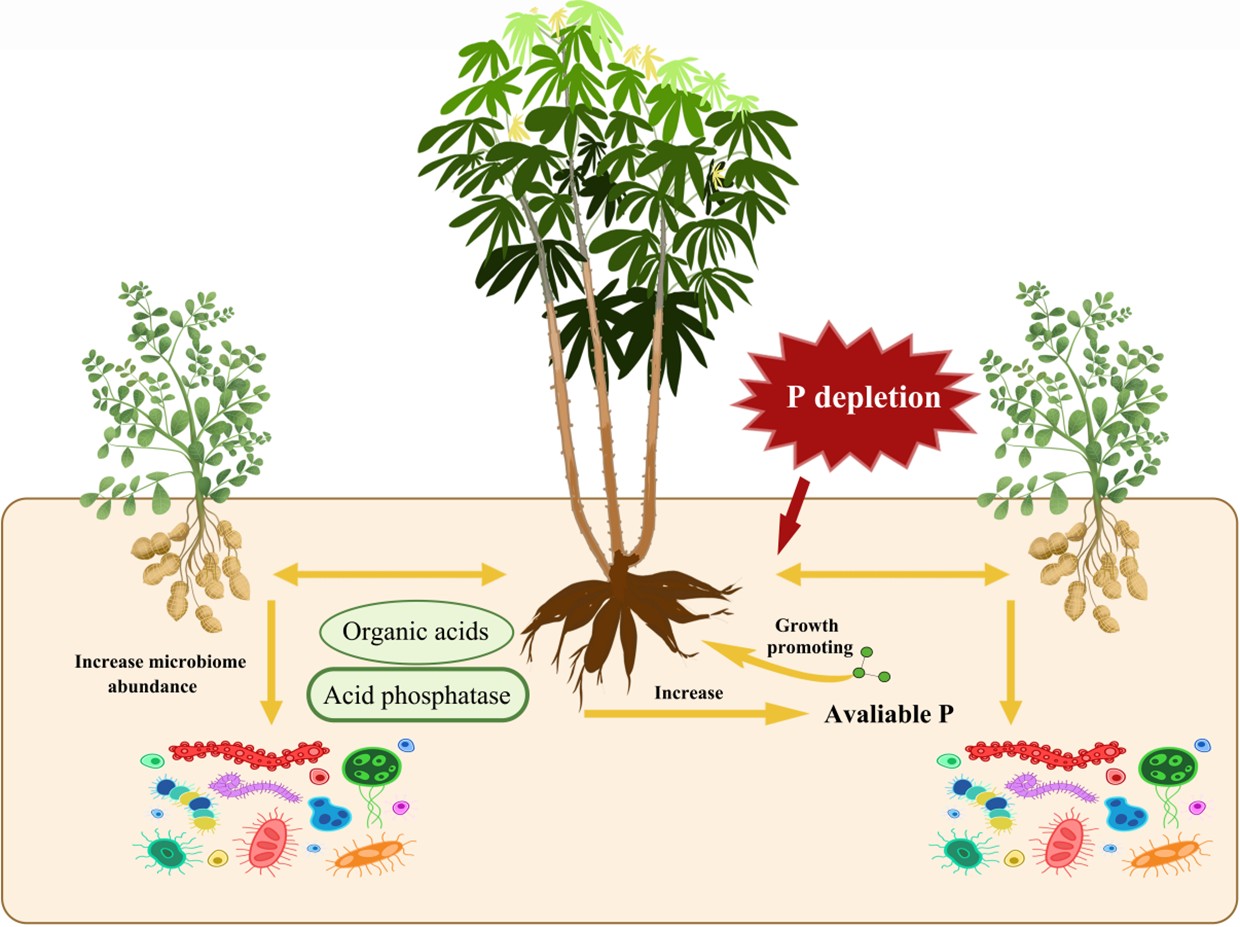

Intercropping is a multiple cropping system in which two or more crops are grown at appropriate spacing during the same growing season. It brings various production benefits, including effects on the functional diversity of the rhizosphere environment, modulating ecosystem-scale CO2 sequestration pathways and nitrogenous compound transformations (including mineralization, immobilization, and nitrification-denitrification cascades), and inhibition of pathogens in the soil[3], enhancing soil nutrient enrichment[4], maintenance of the stability of soil chemical and biological properties and improvement of the rhizosphere community structure[5]. For example, legume intercropping is known for its high yield because of legume nitrogen (N) fixation[6]. Furthermore, white lupin increased the phosphorus uptake of wheat plants. The interspecific phosphorus transfer differentials were evidenced by Cajanus-mediated sorghum phosphorus uptake elevation under low resource supply[7], vs Cicer-induced phosphorus assimilation enhancement in cereal crops (maize: 23.1%, wheat: 19.4%)[8]. These intercropping advantages originate from rhizospheric biochemical reprogramming involving acid phosphatase activation coupled with malate/citrate exudation fluxes, establishing localized phosphorus desorption hotspots[9]. Enzymes like phytase and carboxylates are released by plant roots under phosphorus deficiency[10], enhancing biogeochemical cycling efficiency of soil phosphorus pools through phytoavailable fraction activation and optimized rhizosphere phosphorus dynamics[11]. The biological processes of plants show great association with the transformation of the application form of phosphorus in soil, and various microbial taxa play pivotal roles in regulating phosphorus transformations[12]. Many results have confirmed that rhizosphere bacteria, which are recruited from the intercropping system, can help turn various types of phosphorus not directly available into PO4− by generation of phosphatases, proton (H+), and cation-chelating compounds[11,13]. Meanwhile, some studies similarly found that fungi also increased activation of phosphorus, through plant roots interacting with the soil[14]. Fungal-derived H+ and organic acids significantly modulate soil aggregation and root architecture through mycorrhizal networks, consequently altering phosphorus bioavailability. Phosphorus limitation induces substantial upregulation of root-secreted acid phosphatases in lupin, maize, and chickpea[15,16]. Globally, 40% of agricultural lands face acute available phosphorus scarcity, with tropical acidic soils exhibiting severe phosphorus immobilization mediated by elevated iron/aluminum oxides[17]. Consequently, optimized intercropping systems have emerged as an effective strategy to enhance soil nutrient dynamics, particularly in phosphorus mobilization.

Furthermore, existing research literature demonstrates that the implementation of intercropping systems induces dynamic shifts in rhizospheric microbiota profiles, thereby regulating nutrient translocation networks and biogeochemical cycling efficiencies. Agronomic investigations reveal that in lilium-maize polyculture configurations, rhizosphere microbial consortia exhibit structural realignments characterized by: (a) 45%–62% reduction in pathogenic fungal colonization (particularly Fusarium and Funneliformis genera) compared to monoculture benchmarks; (b) 2.3-fold enrichment of oligotrophic bacterial taxa (Sphingomonas and Nitrospira spp.) involved in nitrogen-phosphorus synergism[18]. Intercropping can not only change the composition and abundance of the microbiome in the underground environment, but also directly or indirectly improve the utilization of nutrients in the soil by releasing various chemicals or acting on the plants, and eventually enhance plant growth[19].

Contemporary agricultural research has extensively explored the effects of interspecies cultivation on plant quality and rhizosphere microbiota across various crop combinations. Nevertheless, the specific impacts of legume-cassava polyculture systems on host plant development and root-zone ecology remain poorly understood. Scientific evidence highlights the critical influence of subterranean storage organs in tuberous crops, where microbial community dynamics significantly determine growth patterns and productivity outcomes[20]. Three distinct leguminous species were employed as green manure partners within a cassava-based intercropping system. This experimental design aims to address two fundamental questions: whether leguminous companion planting enhances cassava yield parameters, and how such cultivation practices modify rhizospheric microbial profiles. The results obtained offer novel perspectives for advancing sustainable cultivation practices in cassava agronomy.

-

The agronomic trials were located at 19°11'–19°52' N, 108°56'–109°46' E (elevation 150 m), within a conserved latosolic red soil zone of Danzhou, Hainan Province, China. This subtropical coastal region exhibits monsoonal climate patterns, characterized by an average annual temperature of 26.7 °C, annual precipitation of 182.5 mm, and average annual sunshine duration of 253.4 h. The soil type at the site is red loam. The experimental cassava variety was SC9, planted in 6 m × 1.2 m rows with 1 m spacing between the rows and 1 m between plants. The seeds of peanut, Macrotyloma uniflorum 'Yazhou' and Stylosanthes were mixed with soil and planted evenly in the cassava rows using strip seeding, forming three intercropping treatments: T1 (cassava-peanuts), T2 (cassava-Macrotyloma 'Yazhou'), and T3 (cassava-Stylosanthes). Monoculture was set as the control group. Twelve field plots were established in the study, where all treatments were conducted in three independent replicates. One empty row was set between every two rows. The cassava plants were cultivated in the field by the double-line planting method (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Under different green manual treatments, a row adjacent to cassava and green manure was selected in April, July, and October, and soil samples were taken from places equidistant from cassava and green manure, and the same position was taken for control. The sampling methods were all multi-point sampling (18 samples were randomly taken in each plot). The collected samples were all 0–20 cm soil layer (3.8 cm in diameter), which were mixed evenly and put into sterile bags, brought back to the laboratory with ice boxes, and stored in the refrigerator at 4 °C and used for microbial biomass analysis; following standardized dehydration under atmospheric conditions. The remaining specimens were subjected to comprehensive soil biogeochemical assessments.

After the tubers were extracted, the adhering soil was gently shaken off to eliminate the bulk of the substrate. Following this, the tubers underwent a thorough washing process with water, followed by a double sterilization procedure involving 75% alcohol and a sodium hypochlorite solution with 1% active chlorine, aimed at eliminating most of the rhizosphere-associated microorganisms. Subsequently, the tubers were rinsed with sterile water, dried using sterile filter paper, and then transferred into sterile bags. All samples were then preserved at −80 °C in liquid nitrogen until DNA extraction was conducted.

Measurement of nutrients

-

Cassava tubers were first heated at 105 °C for 30 min and then lyophilized at −80 °C until reaching a constant mass to assess moisture content. For ash content measurement, samples were combusted at 550 °C for 4 h, followed by gravimetric quantification of the residue. Starch levels were analyzed via acid hydrolysis according to the specifications of Method II in Chinese national standard GB 5009.9-2016[20]. Concentrations of micronutrients, including Mn, Zn, Ca, K, and Na, were quantified using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) coupled with microwave-assisted digestion, adhering to the protocol established by Wen et al.[21].

Measurement of soil N and P contents

-

Rhizosphere soil samples were analyzed for alkali-hydrolyzable nitrogen levels via the Kjeldahl method (FOSS Kjeltec 8400, Denmark). Available phosphorus (AP) in soil was quantified using a molybdenum blue colorimetric assay[22], while alkaline hydrolyzable diffusion techniques were applied to isolate soil available potassium (AK)[23].

DNA extraction and Illumina MiSeq sequencing

-

To prepare the tuber samples for endophytic flora extraction, they were first pulverized into a fine powder using a liquid nitrogen grinding technique. Following this, genomic DNA was isolated from both the freeze-dried tuber powder (50 mg) and soil samples (0.2 g) employing E.Z.N.A.™ Mag-Bind Soil DNA Kits (Omega, USA), adhering strictly to the manufacturer's protocol. To confirm the extraction of sufficient high-quality genomic DNA, its concentration was quantified using a Qubit 2.0 instrument (Life Technologies, USA). Subsequently, the 16S rDNA V3-V4 region was amplified using KAPA HiFi Hot Start Ready Mix (2 ×) from TaKaRa Bio Inc., Japan, and custom barcoded primers. These primers targeted specific gene regions: 341F (50-CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-30) and 805R (50-GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-30). The PCR setup included 2 µL of target DNA (10 ng/µL), 15 µL of 2 × KAPA HiFi Hot Start Ready Mix, 1 µL each of forward and reverse primers (10 µM), and 11 µL of sterile distilled water, culminating in a 30 µL reaction volume per tube. This rigorous methodology ensured the precise and reliable amplification of the targeted DNA regions, facilitating downstream analysis of the endophytic flora.

Following sealing, the samples underwent polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in an Applied Biosystems 9,700 thermal cycler (USA). The initial PCR protocol comprised a 3 min denaturation at 93 °C, succeeded by five cycles of 94 °C (30 s), 45 °C (20 s), and 65 °C (30 s), then followed by 20 cycles of 94 °C (20 s), 55 °C (20 s), and 72 °C (30 s), culminating in a 5 min final extension at 72 °C. The resulting amplicons were then subjected to electrophoretic analysis using 1% w/v agarose gels in TBE buffer (composed of Tris base, boric acid, and EDTA). After staining with ethidium bromide (EB), the DNA bands were detected through UV transillumination.

After PCR amplification, bacterial 16S rDNA quantification was conducted with Qubit 3.0 DNA detection kits. Subsequently, the prepared samples were subjected to paired-end sequencing on an Illumina MiSeq high-throughput sequencing platform[24], with sequencing services provided by Sangon BioTech in Shanghai, China. The resulting sequence data from the Illumina MiSeq were processed and analyzed through the Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology (QIIME) toolkit, version 1.8.0[25]. Using PANDAseq, the paired-end reads were assembled into longer contigs, which were then subjected to rigorous quality control, excluding sequences shorter than 200 nucleotides, those with average quality scores below 20, and contigs containing more than three ambiguous bases. The high-quality sequences were then grouped into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) at a 97% similarity threshold and taxonomically annotated using the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) and Silva bacterial databases to explore their phylogenetic relationships and relative abundances[26]. Sequences flagged as unclassifiable or identified as chimeras were carried by UCHIME[27].

Bioinformatics and statistical analysis

-

Bioinformatics analyses were conducted in R software (v4.0.2), including data visualization via the 'ggplot2' package. To assess microbial community composition, the 'vegan' package was employed for calculating organism counts and taxonomic abundances derived from the 16S rRNA gene OTU table. Relative microbial abundances were determined across all samples through total sum scaling normalization, with results expressed as percentage values. Community diversity metrics—such as species richness (estimated via the abundance-based coverage estimator, ACE) and the Shannon diversity index—were computed using the mothur online platform[28].

The methodological workflow modifications are detailed in mothur's official documentation. Statistical comparisons for bacterial counts and α-diversity metrics between tuberous roots and rhizosphere soil samples were conducted using either Student's t-test or two-way ANOVA complemented with Duncan's post-hoc analysis. Data visualization was accomplished through Excel 2019 (Microsoft Corp.), while all hypothesis testing was executed in SPSS 20.0 with a predefined significance threshold of α = 0.05, which served as the statistical significance criterion throughout this investigation.

The influence of diverse intercropping arrangements on core and unique microbial OTUs in tubers and rhizosphere soil was investigated using established methods[29]. Core microbiomes comprised OTUs common to all replicates across systems, while unique microbiomes consisted of system-specific OTUs. Microbiome variations among cassava genotypes were statistically analyzed via one-way ANOVA and the LSD test (p < 0.05), with results visualized in Venn diagrams. PCA further characterized microbial community differences across treatments.

-

The different farming modes positively influenced cassava starch and nutrient content traits. The content of starch in Macrotyloma uniflorum 'Yazhou'-cassava, Stylosanthes-cassava, and peanut-cassava intercropping modes increased by 1.85%, 9.17%, and 22.3%, respectively, compared to that in the monocropping cassava system (Table 1).

Table 1. Contents of solid matter in cassava after intercropping with different legumes (%).

Number Moisture content Ash content Starch content CK 5.32 ± 0.13 a 1.54 ± 0.04 b 69.03 ± 25.54 b T1 4.91 ± 0.33 b 2.30 ± 0.03 a 84.42 ± 13.10 a T2 4.11 ± 0.17 b 2.07 ± 0.04 ab 70.31 ± 15.04 b T3 5.26 ± 0.16 a 2.28 ± 0.02 ab 75.36 ± 17.81 ab CK: Monoculture; T1: cassava-peanuts; T2: cassava-Macrotyloma 'Yazhou'; T3: cassava-Stylosanthes. Different lowercase letters represent contents of solid matter of different treatments has significant differences (p < 0.05). After intercropping with different legumes, the moisture content declined significantly compared with monocropping, while the content of ash in the cassava displayed a reverse trend. Compared with single cropping, the moisture content of cassava was decreased to different degrees when intercropping with legumes, and the decrease was the highest (22.7%) when intercropping with Macrotyloma uniflorum 'Yazhou'. Intercropping with peanut decreased by 7.71%. After interplanting with stylosanthes, its moisture content decreased the least, by 1.13% (Table 1).

In addition, the experiment also found that cassava and three different legumes intercropping changed their main mineral content. Various mineral elements always show certain effects on human body health and can be an important index to measure cassava quality. Mineral elements (Ca, K, Fe, Mg, Mn, and Na) showed a certain degree of increase after intercropping, especially Zn, which increased significantly under cassava-Stylosanthes intercropping modes. Among them, intercropping with Stylosanthes showed the highest increase by 58.7% (Supplementary Table S1), while it increased by 38.8% and 36.2% after being treated with peanut and Macrotyloma uniflorum 'Yazhou'. In summary, legume intercropping can significantly improve the quality of cassava itself, increase the yield of its economic products, and increase the economic value of the crop.

Intercropping legumes enhanced content of soil AP

-

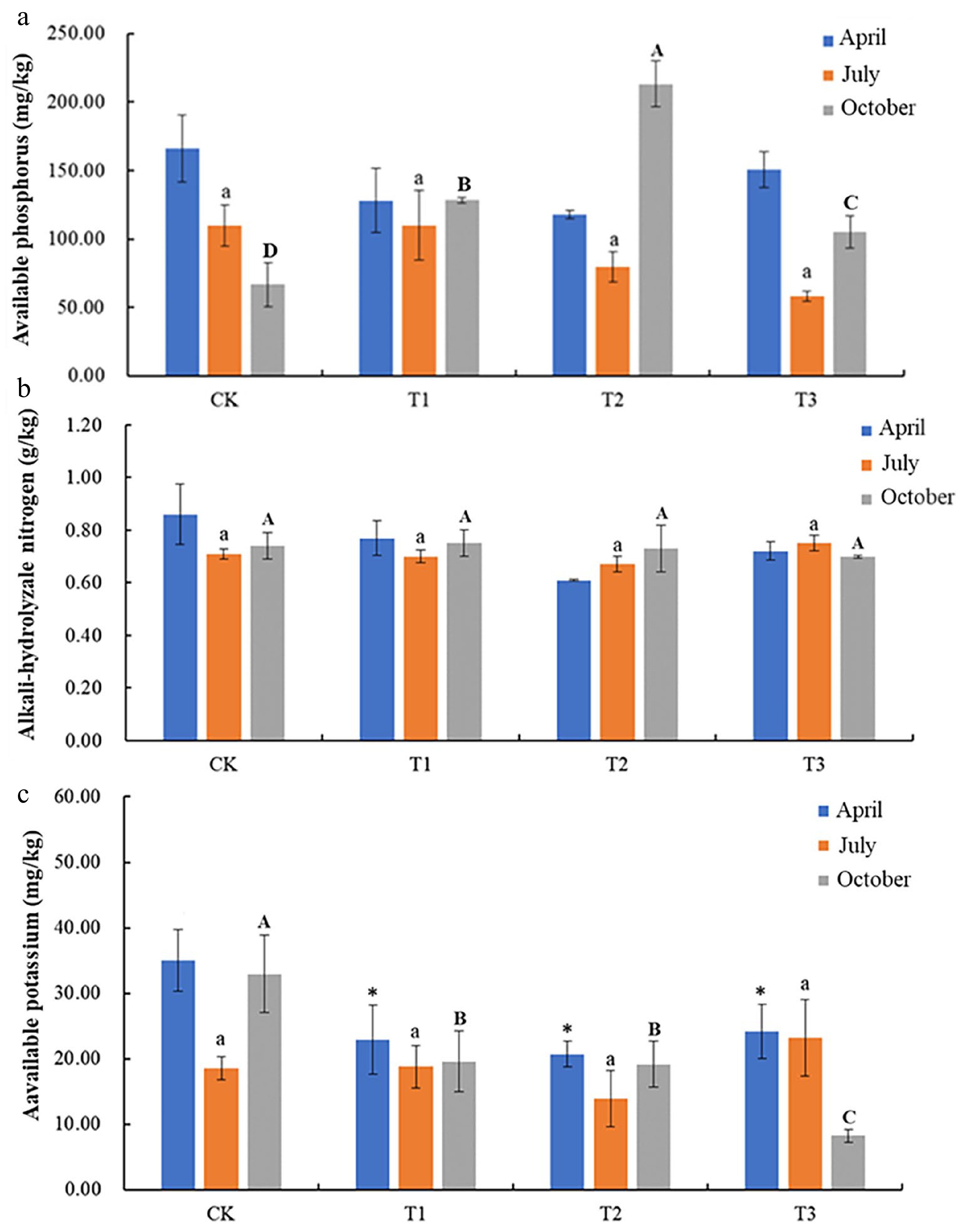

It was found that the contents of alkali-hydrolyzable nitrogen and AK in cassava rhizosphere soil did not show significant changes after intercropping with different legumes (Fig. 1; Supplementary Table S2). However, with the extension of intercropping time, the soil AP content in the intercropping system showed a dynamic changing trend. After six months of intercropping, the soil AP content increased about three times compared with the control. In the treatment group, it was found that soil AP content continued to decrease in the stages of plant growth, indicating that plant growth would continue to consume soil AP. Soil AP content was measured in April and July, and compared with the control group, soil AP content of all treatment groups showed a certain decrease, but not significantly. In October, the AP content of the three treatments increased significantly compared with the control, and the increase was the highest when intercropping with Macrotyloma uniflorum 'Yazhou', with an increase of 167.91%, followed by Stylosanthes treatment with an increase of 80.81%, and the increase of 16.53% was the least after intercropping with peanuts.

Figure 1.

Changes in soil contents of (a) AP, (b) alkali-hydrolyzable nitrogen, and (c) available K, under intercropping of peanut, stylosanthes, and hyacinth bean. Error bar represents standard deviation (SD). According to Duncan test, '*' represents soil available potassium content of different treatment in April has significant differences (p < 0.05); different lowercase letters represent soil available potassium content of different treatment in July has significant differences (p < 0.05); different capital letters represent soil available potassium content of different treatment in October has significant differences (p < 0.05).

These results indicate that legumes can effectively increase soil AP content at the later stage of cassava growth, thereby helping cassava plant growth.

Different intercropping crops affected the distribution of dominant colonies in cassava rhizosphere soil

General characteristics of 16S rDNA/ITS base on sequencing data

-

In this investigation, microbial community analysis through MiSeq sequencing generated 2,101,202 bacterial sequences and 2,046,262 fungal sequences across experimental conditions (each dataset comprised three intercropping configurations with four biological replicates). Following quality control procedures, 2,091,840 bacterial reads and 2,017,171 fungal reads were retained for subsequent analysis. Using a 97% sequence similarity threshold, these sequences were grouped into 3,706 bacterial operational taxonomic units (OTUs) and 3,885 fungal OTUs. Taxonomic classification revealed distinct microbial diversity, with bacterial communities spanning 23 phyla and 409 genera, while fungal populations encompassed 14 phyla across 795 genera.

Microbial diversity improves in response to different intercropping modes

-

The microbial α-diversity was evaluated using the tuber and rhizosphere microbial richness abundance based coverage estimator (ACE) and the microbial Shannon index, and had a statistical analysis performed with different intercropping treatments. There were no significant differences in bacterial richness (ACE) and the bacterial Shannon index. Moreover, variations in fungal α-diversity among bacterial communities were evaluated using either the t-test or a two-way ANOVA complemented by Duncan's multiple range test, with statistical significance determined at p < 0.05. Our results showed that the rhizosphere had a higher α-diversity (Supplementary Fig. S2) than that of tubers. After comparison of the three systems, the diversity of fungal α-diversity increase was observed in both root tuber and rhizosphere soil, and the increase was more significant in the rhizosphere soils. Among them, the diversity of Stylosanthes intercropping increased significantly compared with the control.

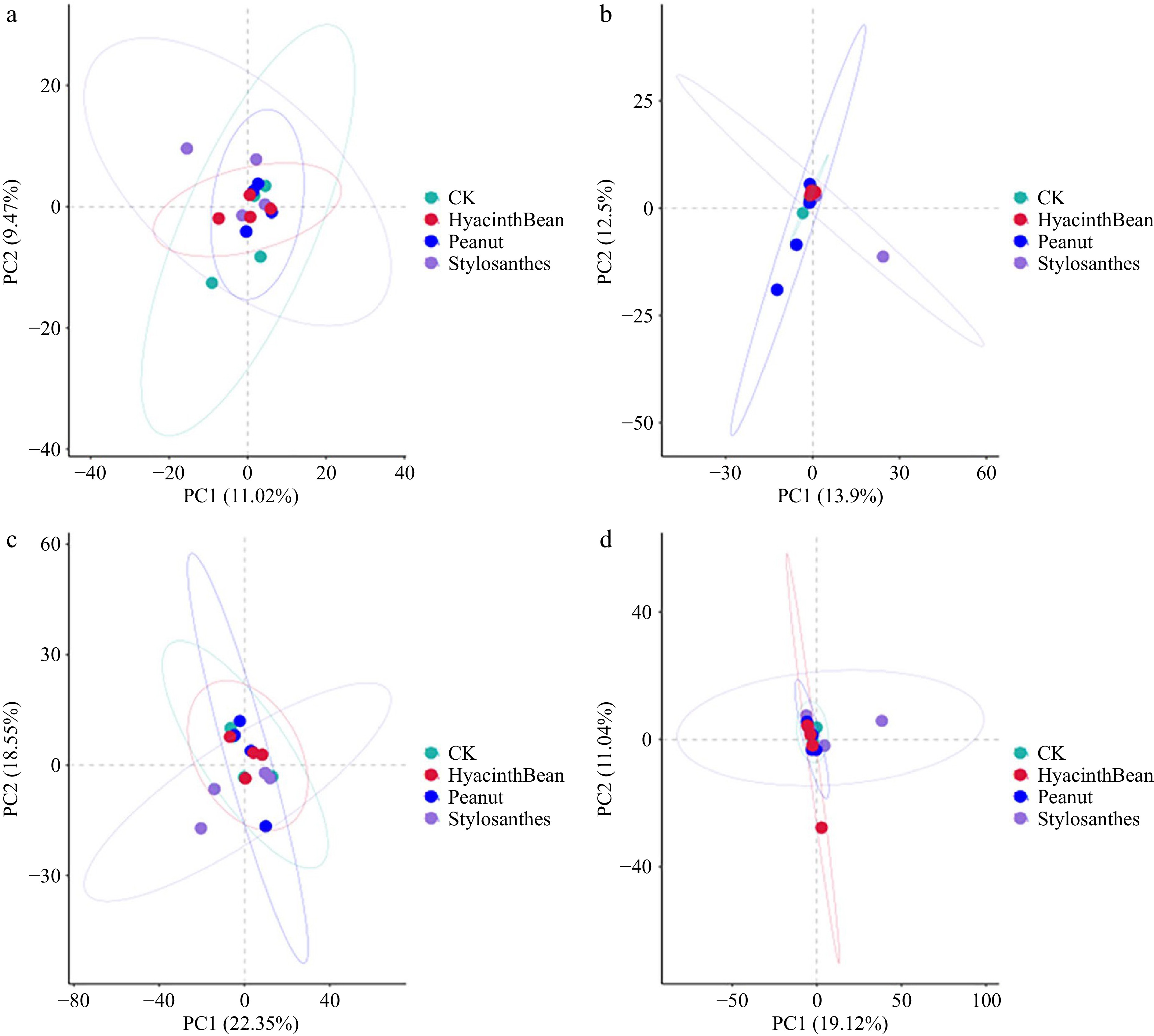

PCA plots showed that bacterial and fungal communities in the tubers and rhizosphere soil were not clearly separated. A total of 20.49% (11.02% and 9.47%), and 26.4% (13.90% and 12.50%) of the overall bacterial and fungal variation in tubers was found (Fig. 2). Meanwhile, the bacterial communities explained 40.9% (22.35% and 18.55%) and fungal communities explained 30.16% (19.12% and 11.04%) of the overall variation in the rhizosphere soil. No clear separation was observed among the samples based on different intercropping patterns.

Figure 2.

Principal component analysis (PCA) analysis of microbial community. (a) Bacterial communities in tubers. (b) Fungal communities in tubers. (c) Bacterial communities in the rhizosphere soil. (d) Fungal communities in the rhizosphere soil.

The above results indicate that intercropping of different leguminous plants has little effect on the diversity of microorganisms in the cassava rhizosphere.

Microbial taxonomic analysis at the phylum level

-

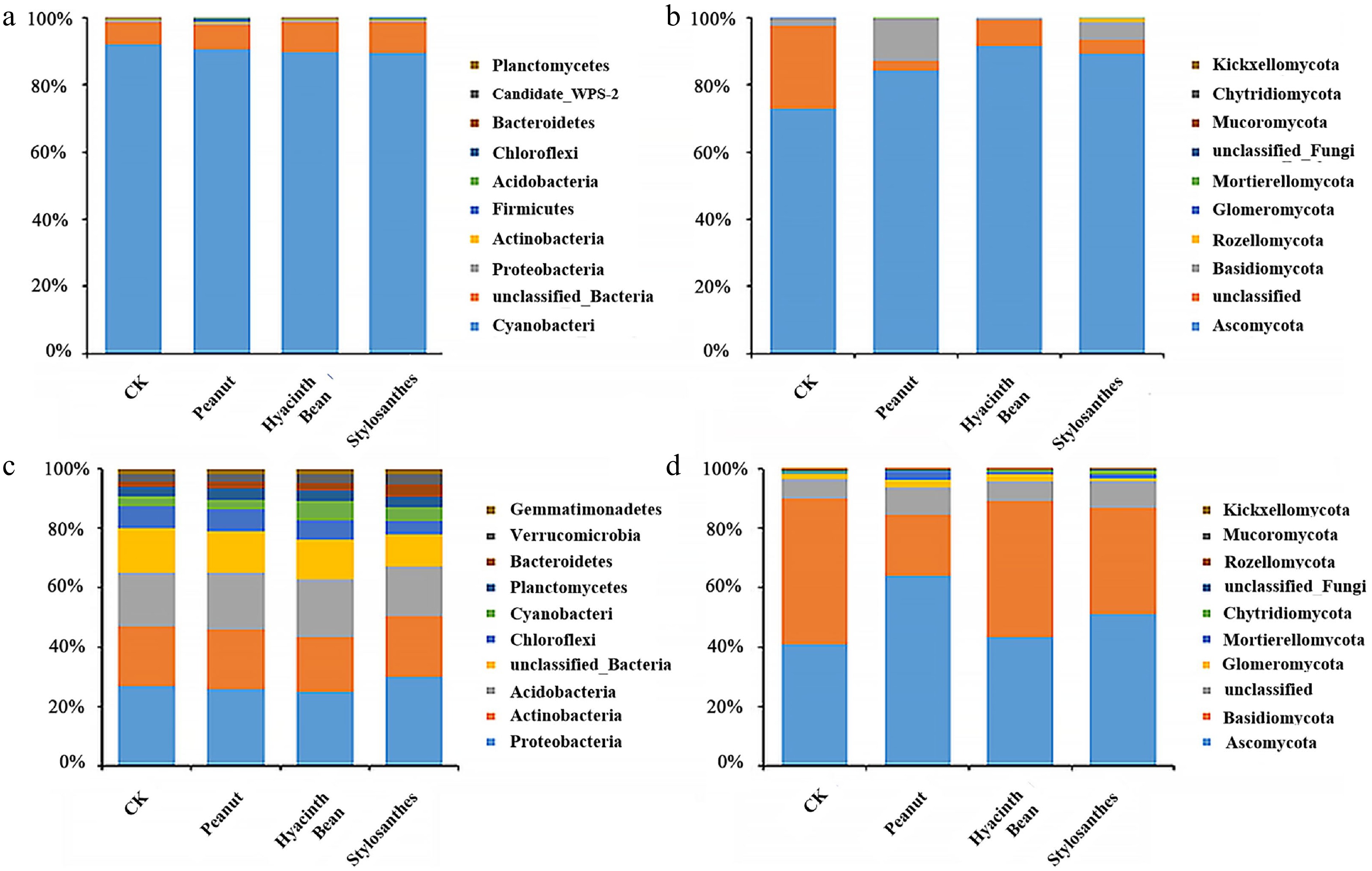

Microbial community profiles of the ten most prominent phyla in tuber and rhizosphere regions are displayed in Fig. 3. Examination of fungal populations identified Ascomycota as the predominant phylum (> 10% relative abundance) in all tuber samples, making up 73.1%–91.6% of total high-quality sequences. All of them showed great change trends under different legumes intercropping systems, and after intercropping with Macrotyloma uniflorum 'Yazhou', the most significant increase was displayed, reaching 25.33%, while Acidobacteria in tubers showed increase.

Figure 3.

Histogram of the relative abundances at the phylum level of the top ten bacterial and fungal communities in tubers and the rhizosphere soil of different intercropping modes. (a) Bacterial communities in tubers. (b) Fungal communities in tubers. (c) Bacterial communities in the rhizosphere soil. (d) Fungal communities in the rhizosphere soil.

In the rhizosphere soil, clear dominant bacteria were found. The abundances of Actinobacteria, Acidobacteria, and Proteobacteria were high compared with those in the rhizosphere soil samples, accounting for 17.42%–19.57%, 16.16%–18.57% and 23.87%–28.79%, respectively, as shown in Fig. 3. However, among the dominant rhizosphere bacteria, few bacteria showed significant changes compared with controls. Ascomycota and Basidiomycota were the dominant phylum in the rhizosphere. Interestingly, fungi Ascomycota showed increase after planting with legumes, while Basidiomycota showed a downward trend, compared with monoculture.

In summary, under the intercropping conditions of different leguminous plants, the composition and structure of fungi in the rhizosphere environment changed significantly, but the structural changes of bacteria were not obvious.

Changes in microbial community structures at the genus level

-

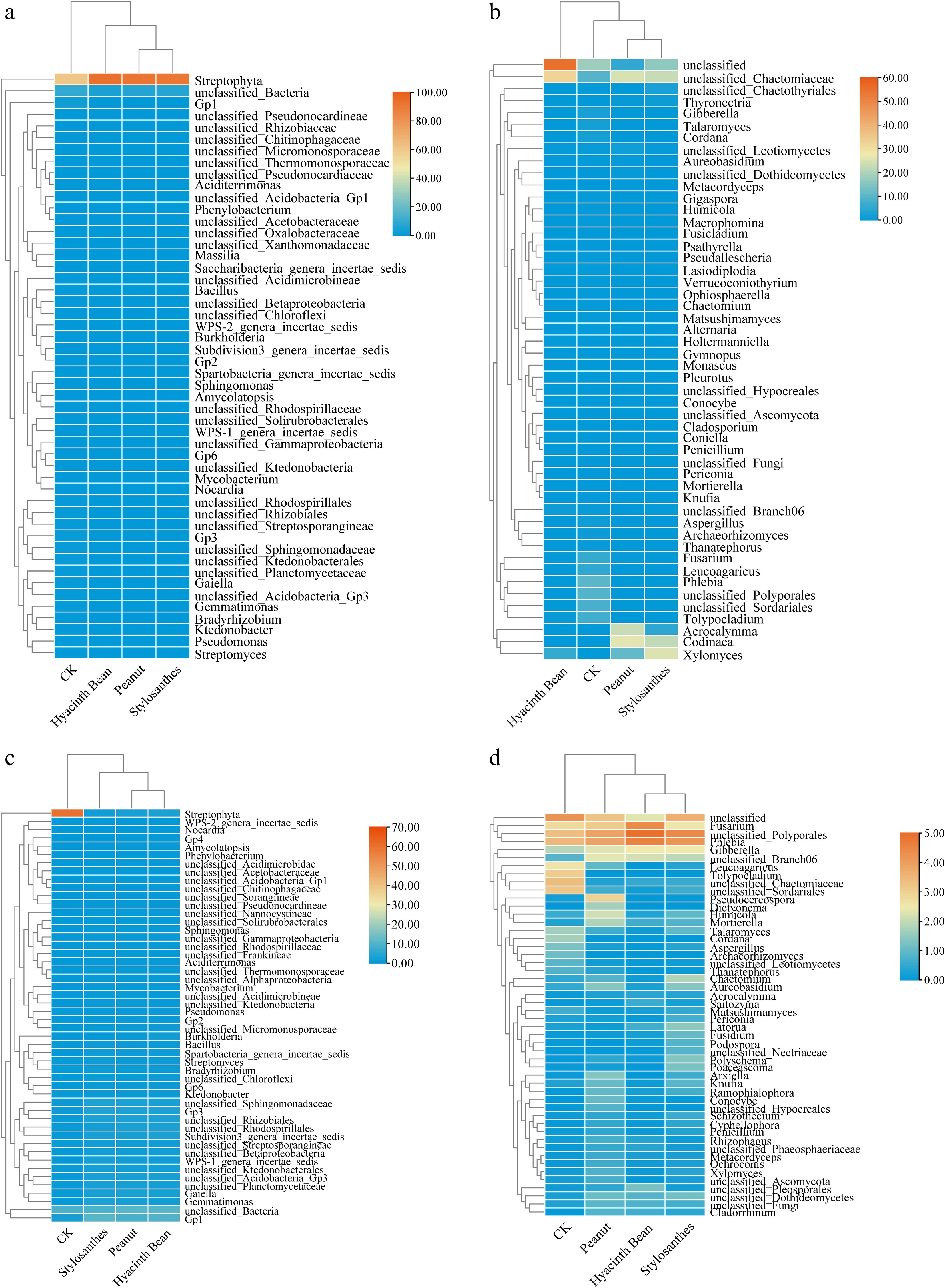

Through a detailed analysis of the heatmap depicting the distribution patterns of the 50 most prevalent microbial genera, no significant difference was observed in bacterial community structures after intercropping (Fig. 4a, c). However, in the rhizosphere soil, there were endemic bacteria Corynebacterium after intercropping with peanut, and Rummeliibacillus, unclassified-Ruminococcaceae, and Fluviicola were unique in rhizosphere bacterial community. Gaiella (1.98%), Gemmatimonas (1.85%), Bradyrhizobium (1.55%), Streptomyces (1.41%), Ktedonobacter (1.37%), and Burkholderia (1.24%) were also abundant classified bacteria in treatment groups.

Figure 4.

Heatmap of the relative abundances at the genus level of the top 50 bacterial communities in the tubers and the rhizosphere soil of different intercropping treatments. (a) Bacterial communities in tubers. (b) Fungal communities in tubers. (c) Bacterial communities in the rhizosphere soil. (d) Fungal communities in the rhizosphere soil.

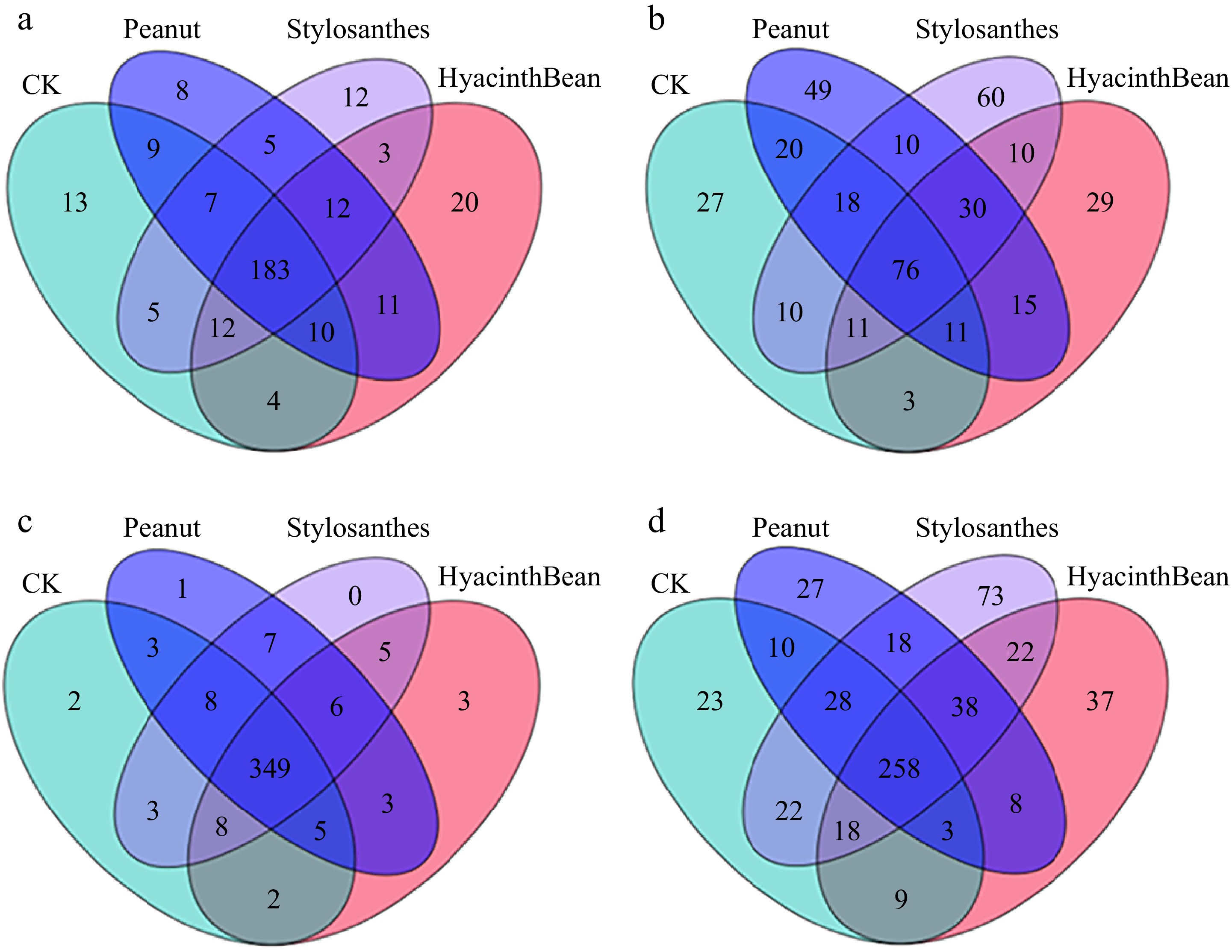

The composition of fungal genera exhibited significant variation across the various samples analyzed. Notably, three specific genera: unclassified-Polyporales, Phlebia, and Fusarium, dominated in all rhizosphere samples, with their relative abundances ranging between 8.1% to 20.31%, 5.7% to 19.1%, and 7.8% to 14.5%, respectively. Despite the differences in intercropping patterns, the core fungal genera in the rhizosphere soils displayed remarkable consistency. A total of 258 core fungal genera were identified, representing 43.4% of the entire rhizosphere fungal community, as illustrated in Fig. 5d. Statistical analysis revealed that the relative abundances of the majority of these core bacterial genera varied significantly across different treatments (p < 0.05). In the cassava tuber, the abundance of unclassified-Chaetomiaceae, Acrocalymma, Codinaea, and Xylomyces showed an increase trend, while Fusarium, Phlebia, and Gibberella increased in rhizosphere soil. Meanwhile, the abundance of Leucoagaricus and Tolypocladium indicated a decline trend (Fig. 4b, d).

Figure 5.

Number of bacterial and fungal genera in the tuberous roots and the rhizosphere soil of different intercropping modes. (a) Bacterial communities in tubers. (b) Fungal communities in tubers. (c) Bacterial communities in the rhizosphere soil. (d) Fungal communities in the rhizosphere soil.

After the β diversity analysis of cassava rhizosphere soil microorganisms, it was found that there was little difference in the composition of the bacterial population between different treatments, and the core community was basically the same. In the control group, two unique bacteria existed, Georgfuchsia and Corynebacterium. There was a specific bacterial group, Peredibacter, in peanut-cassava intercropping mode. The endemic bacteria genera were Rummeliibacillus, unclassified-Ruminococcaceae, and Fluviicola. There was no specific strain after interbreeding with Stylosanthes. In contrast, there were some differences in the abundance of fungal communities, but the differences were not obvious, and the core microbial groups accounted for a higher proportion of the total number of microorganisms among different treatments, and their community structure was highly similar (Fig. 5c, d). These results indicated that intercropping of different legumes had no significant effect on the categories of microbial community in rhizosphere soil, and the main change was the quantity and abundance of each bacterial genus. At the same time, it was found that there was no obvious separation of microbial communities in cassava roots of different treatments, and the core microbial groups accounted for a higher proportion of the total number of microorganisms, and their community structure was highly similar (Fig. 5a, b). The results showed that intercropping of different legumes had no significant effect on the composition of microbial community, and the main change was the quantity and abundance of each bacterial community.

In summary, after intercropping with different legumes, the quantity and abundance of microorganisms in cassava rhizosphere soil changed to some extent. It was found that the relative abundance of fungi varied greatly in different intercropping systems, indicating that legumes were more likely to affect rhizosphere fungi in the compound planting system.

Effects of microbial communities on soil alkali-hydrolyzable nitrogen, AP, and AK content

-

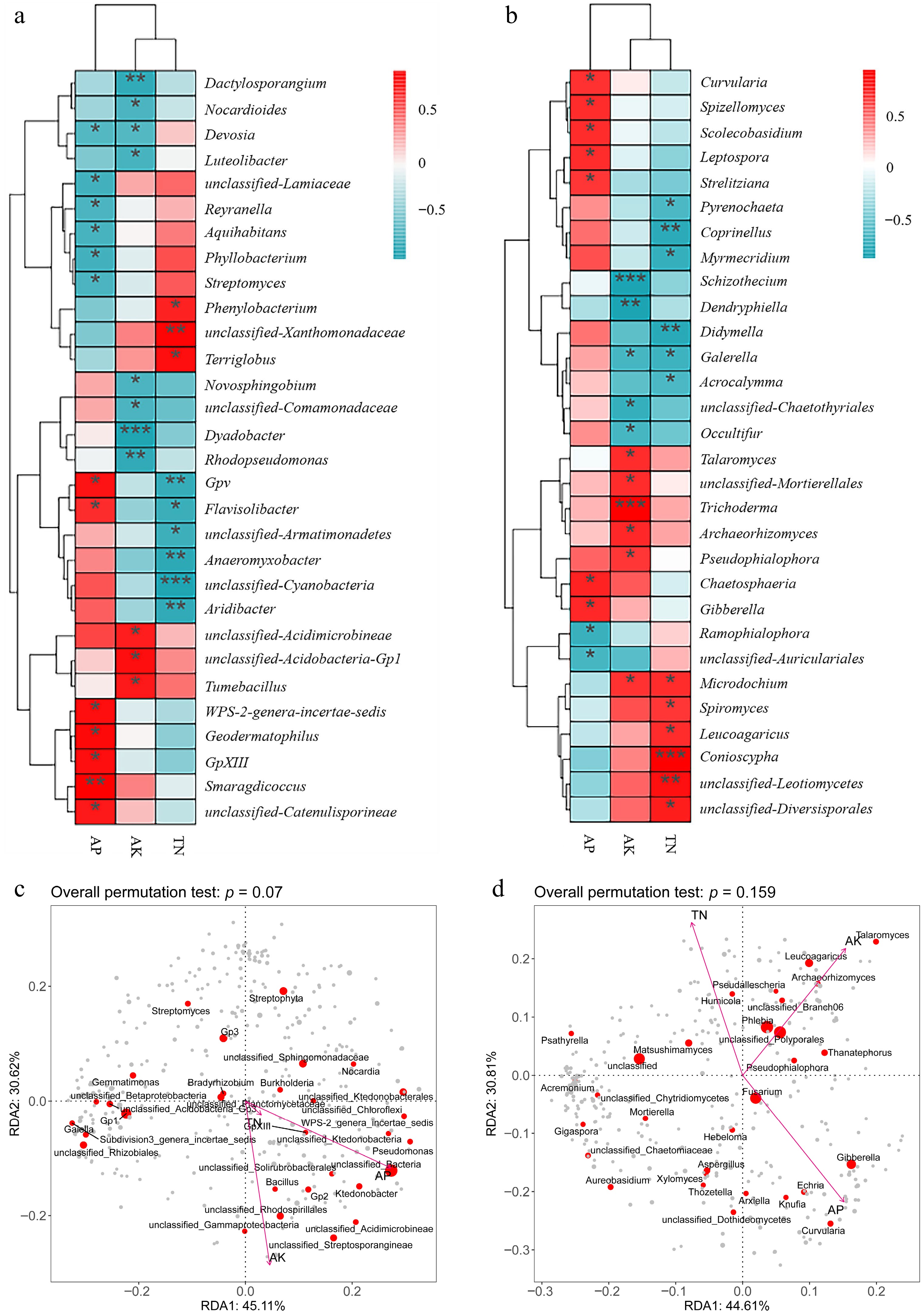

To explore the relationship between microbial communities and soil nutrients, correlation and RDA redundancy analysis were carried out. The results showed that there was a difference in the microbial composition, which showed a positive correlation with soil AP, AK, and alkali-hydrolyzable nitrogen. The microbial community, which was positively correlated with AP, displayed the highest abundance, while the microbial community that was correlated with alkali-hydrolyzable nitrogen was generally more strongly correlated. Conioscypha showed the strongest correlation soil with alkali-hydrolyzable nitrogen, while Trichoderma and AK content correlated significantly positively (Fig. 6). At the same time, it was found that after intercropping, the species abundance related to soil phosphorus utilization, such as Acrocalyma and Gibberella showed an increasing trend (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Correlation analysis. (a) Bacterial communities in the rhizosphere soil. (b) Fungal communities in the rhizosphere soil and RDA redundancy analysis. (c) Bacterial communities in the rhizosphere soil. (d) Fungal communities in the rhizosphere soil of rhizosphere microorganisms and rhizosphere soil fertility in cassava after intercropping with different legumes. Asterisks indicate significant differences in correlation (ANOVA, FDR-corrected LSMeans, *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001).

In summary, intercropping with legumes could improve the composition of microbial community in cassava rhizosphere, the abundance of fungi showed great enhancement, including Gibberella, Acrocalyma, and Basidiomycetes, which increases the availability of phosphorus in soils, while the abundance of bacteria showed no significant change.

-

As in a previous study, legume intercropping has the quality of increasing phosphorus use efficiency in agriculture[30]. Many results have proved that the legumes intercropping mode show great qualities in improving the substantial use efficiency and phosphorus uptake. Nielsen & Jensen[31] found that high-efficiency root interactions are necessary for nutrition utilization in barren soils and low-input agroecosystems, depending on interspecific competition, which is critical for plant growth. By improving the change and utilization of N and P, intercropping may affect crop yields compared with monoculture[17]. Analysis of the data reveals a significant transformation in the AP levels within the root zone soil resulting from the cultivation of peanut plants in mixed cropping arrangements. The soil AP content of Macrotyloma uniflorum 'Yazhou' intercropping showed a trend of decreasing first and then increasing. After intercropping, the AP content of the soil increased significantly compared with the control. Phosphorus is the most limiting factor for plant growth[32]. While phosphorus is naturally present in substantial quantities within the soil, a significant proportion exists in insoluble forms, rendering it largely inaccessible for plant uptake and utilization. This limitation becomes particularly pronounced in low-input agricultural systems, where the availability of inorganic phosphorus is inherently constrained. Within such systems, legume intercropping has emerged as an effective strategy for improving phosphorus acquisition, as evidenced by a previous study[33]. Research conducted in semi-arid regions by Adesoji et al.[33] further highlights the transformative impact of legume incorporation on soil chemistry and fertility. Species such as lablab, soybean (Glycine max), and mucuna (Mucuna pruriens) have demonstrated measurable enhancements in soil chemical properties when introduced into cropping systems. Furthermore, the observed increases in soil acid phosphatase activity (RS-APase and BS-APase) and S-APase levels suggest a potential mechanism underlying the improved phosphorus nutrition observed in intercropping configurations. Yuan et al.[34] proved that the litchi-legumes intercropping system could increase the contents of soil ammonium nitrogen and available phosphorus compared with the monoculture pattern. It turns out that intercropping can significantly improve soil nutrients to aid plant growth, as described in the results of this paper.

Intercropping systems improve the microbial community in cassava rhizosphere

-

The rhizosphere, defined as the soil region shaped by the complex interplay of plant roots and microorganisms, represents a crucial ecological niche[35]. Evidence suggests that various sustainable farming techniques can dramatically modify the microbial abundance and species diversity in soil ecosystems[20,36]. In this study, the dominant phyla, such as Ascomycota, Acidobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Proteobacteria, all showed an increase after intercropping with different legumes (Fig. 2). Studies have previously identified Actinobacteria as a key player in pathogen suppression[37]. In soil environments, Acidobacteria, a bacterial group characterized by its abundance and widespread distribution[38], is essential for organic matter breakdown and nutrient cycling processes[39].

As a prevalent strain, Acrocalymma is highly researched among dark septate endophytes (DSE), a group of conidial or sterile ascomycetous fungi that thrive in the roots of mycorrhizal and non-mycorrhizal plants[40]. Characterized by their dark septate hyphae and melanized microsclerotia, DSEs exhibit unique structural traits that set them apart[41]. Related reports showed that DSE is able to participate in the interaction with the host plant through negative to neutral and positive identities[42]. The multifaceted role of DSE fungi in plant development becomes evident through their dual action: improving mineral uptake efficiency while simultaneously reducing the impact of various stress factors that typically limit host plant performance[43].

In line with Keswani et al.[44], experimental results reveal that intercropping boosts bacterial proportions in maize and soybean rhizospheres, whereas fungal populations present a reduction trend in the root environments of both plants compared to monoculture practices. In the peanut-maize cultivation system, the study by Chen et al.[45] revealed distinct differences in the rhizosphere bacterial community's composition and structure between intercropping and sole cropping practices. Notably, the bacterial communities within the intercropping rhizosphere exhibited high levels of similarity, which underscores the significant influence of interspecific facilitations on microbial dynamics. Similar to the experimental results in this study, many dominant bacterial communities showed great association with soil AP, such as Bradyrhizobium, Gemmatimonas, which could significantly improve the content of AP[46]. Research has demonstrated that certain microorganisms are capable of harnessing substantial energy and nutrient resources from cover crops, facilitated by the breakdown of plant residues and root secretions, which subsequently enhances the proliferation of both basal and phosphorus-solubilizing microbial populations, thereby boosting phosphorus-related biological processes[12].

In the past, leguminous plants were often widely used as nitrogen-fixing plants in intercropping systems in the fields. However, with the progress of research, it has been found that leguminous plants have no less ability to stimulate phosphorus in the soil than they do to stimulate nitrogen. Many legume species, such as chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.), white lupin (Lupinus albus L.), and faba bean (Vicia faba L.), have been demonstrated to act as phosphorus-mobilizing plant species, which show the availability in releasing macronutrients and micronutrients in the rhizosphere of cereal-legume intercropping systems[47]. Leguminous plants can release a large amount of secretions from their roots, especially carboxylates. Moreover, intercropping systems, which include organic anions and phosphatases secreted by beneficial fungi and plant growth-promoting bacteria, can activate the phosphorus in the soil and provide a carbon source for soil microorganisms in the rhizosphere, thereby promoting the growth of plants in soils with limited phosphorus. Furthermore, various legume cover crops influence soil microbial functionality by modifying the soil's physical and chemical characteristics[48]. Interestingly, it was noticed that the intercropping of leguminous plants did not significantly affect the nitrogen content in the field soil. This might be because the impact of leguminous plants on nitrogen is mainly in the form of change. Only the content of available nitrogen in the soil was measured, while other nitrogen forms were not assessed. This might have caused a certain degree of influence on the experimental result.

Intercropping improve the rhizosphere environment involving with quality of cassava

-

The practice of intercropping enhances soil fertility, subsequently elevating both crop productivity and nutrient absorption efficiency[6]. As documented by He et al.[49], the maize intercrop with cassava can be identified as a specific cropping pattern in a tropical field due to its ability to improve the nutrients of the rhizosphere environment and adjust the rhizosphere microbial community of plants. Another research conducted by Duan et al.[50] demonstrated that incorporating legumes in intercropping systems notably enhances the synthesis of critical compounds, including soluble sugars, amino acids, and EGCG. These biochemical alterations in quality constituents are fundamentally associated with the improvement of tea quality indices, nutritional value, and health-promoting properties, findings that corroborate the results obtained by Wen et al.[51]. A number of studies have proved that soil nutrition is closely related to crop quality[50,51]. Through the content of soil nutrition, the microbiome shows an increasing trend. Soil microorganisms play a crucial role in phosphorus cycling[52]. Dong et al.[53] suggests that pasture mulching can alter microbial survival strategies by improving the soil's nutrient environment. In this study, it was found that the abundance of microorganisms related to soil phosphorus utilization, such as Acrocalyma and Gibberella, increases greatly after intercropping. Bacterial genera, such as Bacillus and Pseudomonas were more abundant and showed a more positive correlation in the rhizospheric soil of cassava and legumes in intercropping than in the monoculture. It is hypothesized that through the help of these beneficial bacteria exudates, soil phosphorus can be fully released to help plant growth and utilization, thereby helping to improve its quality.

Existing research indicates that arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) play a significant role in phosphorus uptake, accounting for as much as 80% of total phosphorus absorption and potentially decreasing the need for mineral phosphorus by approximately 20%, through the secretion of acid phosphatase enzymes and organic acids[54]. Jin et al.[55] conducted experiments with diverse AM fungal species, soil leachates, and artificial microbial consortia, revealing that in the presence of organic phosphorus, AM fungi preferentially attract specific bacteria, including Streptomyces species. These bacteria improve phosphorus availability for the fungi while outcompeting less efficient phosphorus-mobilizing microorganisms. This interaction is facilitated by carbon compounds released by the fungi, which are utilized by the bacteria to break down organic phosphorus into a usable form.

In the experiment, it was found that the effect of intercropping legume on cassava root tuber microorganisms was greater than that on rhizosphere microorganisms. It was speculated that the growth hormone or metabolic substances secreted by legume affected the rhizosphere environment, and the endophyte community of the root tuber was affected. Li et al.[56] found that intercropping of corn and peanut increased the soil available nutrients (available nitrogen and available phosphorus) and enzyme activities of the two crops. The results showed that the subsurface interaction of the corn/peanut intercropping system played an important role in the changes of soil microbial composition and dominant microbial species, which were closely related to the improvement of soil available nutrients (N, P) and enzyme activities[57]. Root exudates provide nutrients for soil microorganisms. It is speculated that, compared with monocultures, the types and contents of root exudates increased after intercropping, which influenced the activity and diversity of soil microorganisms through selective stimulation of the growth of soil microorganisms.

-

The biomass and yield of cassava increased significantly after intercropping with legumes. The solid content of cassava was changed after intercropping: the ash and starch content of cassava increased after intercropping with different legumes, and the increase of peanut was the most obvious after intercropping.

Intercropping of legumes can affect the soil nutrient content. The three intercropping treatments can significantly increase the content of available phosphorus in cassava rhizosphere soil and increase the accumulation of available phosphorus in soil, and the effect of intercropping of Stylosanthus was the most obvious. After intercropping, there was no significant effect on the diversity of rhizosphere bacteria community, but there was a more obvious effect on the fungal community, and the uniformity of rhizosphere microorganisms was reduced. However, there was little difference in the overall community structure composition, and the abundance of rhizosphere bacteria related to effective phosphorus absorption was increased.

This work was supported by the China Agriculture Research System (Grant No. CARS-11-hncyh), the Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32260468), and the International Science & Technology Cooperation Program of Hainan Province (Grant No. GHYF2024008).

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Chen Y; experiments and data analysis: Zhang R, Zhang Y, Feng Y, Wang R; management of experimental materials: Wang H; draft manuscript preparation: Zhang Y; manuscript revision: Gao Y, Chen Y, Feng Y, Zhang Y. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

accompanies this paper at (https://www.maxapress.com/article/doi/10.48130/tp-0025-0027)

-

Received 7 January 2025; Accepted 17 July 2025; Published online 27 October 2025

-

It is not yet clear how cassava intercropping of legumes would affect the rhizosphere environment

In this study, we intercropped Arachis hypogea, Macrotyloma uniflorum 'Yazhou', and Stylosanthes guianensis under cassava as green manure.

On this basis, we investigate whether the intercropping of different legumes with cassava can improve its yield and affect its rhizosphere microbial composition.

The findings of this study provide new insights for the green production of cassava.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Yijie Zhang, Yating Feng

- Supplementary Table S1 Mineral element contents of cassava after different intercropping treatments (mg/kg).

- Supplementary Table S2 Soil nutrient contents under different intercropping conditions.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Diagram of experimental design.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Tubers and rhizosphere soil microbial Shannon diversity (a bacteria and c fungi) and richness (abundance-based coverage estimator, ACE) (b bacteria and d fungi) after intercropping with different Leguminosae.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Hainan University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang Y, Feng Y, Wang H, Gao Y, Wang R, et al. 2025. Cassava intercropping Leguminosae increases quality of cassava by increasing soil phosphorus availability via altering soil microbial community composition. Tropical Plants 4: e035 doi: 10.48130/tp-0025-0027

Cassava intercropping Leguminosae increases quality of cassava by increasing soil phosphorus availability via altering soil microbial community composition

- Received: 07 January 2025

- Revised: 04 July 2025

- Accepted: 17 July 2025

- Published online: 27 October 2025

Abstract: Agroecological intercropping practices demonstrate dual benefits in pest suppression and soil quality enhancement through diversified planting strategies. Despite these advantages, the current understanding of microbiome dynamics in combined root-legume cultivation remains fragmented, particularly the variations in bacterial populations and structural diversity observed when cassava is introduced into legume-intercropped agricultural models. A field experiment was carried out with four treatments: cassava-peanut (Arachis hypogea), cassava-hyacinth bean (Macrotyloma uniflorum 'Yazhou'), cassava-Stylosanthes intercropping, and cassava monoculture to characterize longitudinal variations in edaphic nutrient cycling and microbiota configuration parameters (including population density, species richness, and consortia architecture) across distinct plant microhabitats—specifically root-soil interfaces and underground storage organs. Results showed that different intercropping modes significantly increased the starch content by 1.85%, 9.17%, and 22.3%, and zinc content by 38.8%, 36.2%, and 58.7% respectively. Intercropping with various legumes improved the content of available phosphorus (AP) in cassava rhizosphere soil by 167.9%, 80.8%, and 16.5%, respectively. It also improved the composition of the microbial community in the cassava rhizosphere and enhanced the growth and abundance of fungi, including Gibberella, Acrocalyma, and Basidiomycetes, which increased the availability of phosphorus in the soil. These results indicated that intercropping of legumes could improve cassava quality, rhizosphere microbial diversity, and soil nutrient utilization.

-

Key words:

- Cassava /

- Legume /

- Intercropping /

- Rhizosphere and non-rhizosphere soil