-

Coffee is the most frequently consumed beverage, as well as one of the most widely produced industrial crops in Thailand. Arabica coffee (Coffea arabica) is popularly cultivated in Northern Thailand. This variety is highly regarded among the several types of coffee beans for its outstanding quality and commercially accepted taste[1,2]. The output volume of Arabica coffee reached 70%, with demand anticipated to increase by around 10% annually[3,4]. In coffee manufacturing, biological losses can reach 40%–45%, encompassing pulp, husk, parchment, and silver skin[5]. It was also estimated that coffee pulp accounts for > 60% of the total biomass generated. This specific contamination issue leads to environmental pollution which results in substantial management costs[6−8]. In light of its accessibility and very low cost, efforts have been undertaken to augment the utility of this agro-industrial biomass by isolating bioactive constituents to value-add it.

The BCG economy, which stands for Bio-Circular-Green economy, refers to a sustainable model integrating waste recycling, resource efficiency, and environmental conservation. To mitigate dependence on synthetic inputs and optimize productivity, the bio-economy component prioritizes the implementation of climate-resilient coffee varieties, bio-based insect control methods, and organic fertilizers. For instance, coffee residue, which is abundant in nutrients and organic matter, can be turned into organic fertilizers through composting or fermentation. This process reduces the necessity for synthetic alternatives, and enhances soil health[9,10]. Furthermore, extracts from coffee husks have shown potential as bio-pesticides against coffee pests, offering a natural and sustainable pest control solution[11]. The circular economy aspect promotes the efficient utilization of agricultural waste, such as coffee pulp and spent grounds, which can be repurposed for bioenergy production, composting, biocontrol, and bioplastics. For example, coffee pulp can be anaerobically digested to produce biogas, a renewable energy source, reducing reliance on fossil fuels[12]. By creating the BCG economy model, the coffee industry can improve its resilience against climate change, stabilize farmers' incomes, and promote sustainable land management. This integrated approach ensures the long-term viability of coffee farming while reducing its ecological footprint and fostering economic sustainability for future generations. This review comprehensively examines biorefinery approaches for the sustainable valorization of coffee biomass within a BCG economy framework. It delineates various biorefinery types and processes applicable to coffee pulp, explores diverse industrial applications of extracted compounds, and analyzes BCG implementation in coffee production. By elucidating future research and industrial directions, this review aims to compile the necessary information for researchers, industry professionals, and policymakers with knowledge to foster a sustainable, economically viable coffee industry, minimizing environmental impact, and maximizing resource utilization.

-

In agriculture, a substantial volume of by-products are typically generated, especially during harvesting and post-harvest procedures. These by-products encompass carbohydrates, fats, lignin, proteins, and, to a lesser extent, various other substances like dyes, vitamins, and flavors. Any organic matter that is available on a renewable or recurring basis, with the exception of old-growth timber, is considered biomass. These materials encompass dedicated trees, agricultural residues, energy crops, wood, animal refuse, aquatic plants, and other sources[13,14]. Previously regarded simply as biomass, these by-products are now seen as important sources for extracting value-added compounds and producing biofuels. A biorefinery combines multiple processes for converting biomass into a variety of valuable outputs, such as chemicals, biofuels, materials, and energy. Unlike traditional refineries, which rely on fossil fuels, the modern biorefineries tap into the potential of biological resources, prioritizing sustainability, and environmental friendliness[15]. The concept of the novel biorefinery and biorefining encompasses various definitions, often shaped by specific contexts. The International Energy Agency[16] describes biorefining as the environmentally conscious and enduring conversion of biomass into a diverse array of commercially viable products and energy sources[16]. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) defines a biorefinery as an integrated facility utilizing various biomass conversion processes and equipment to generate fuels, power, and chemicals from agricultural, forestry, and waste feedstocks[17]. However, a recent concept has emerged, highlighting the utilization of biomass as a raw material to create a diverse range of value-added products through sophisticated processing techniques. Subsequently, a more comprehensive definition has been proposed, defining the term 'biorefinery' as a facility that uses physical, chemical, or biological processes to convert biological materials from various natural sources such as plants, animals, and fungi into usable products or materials for other products[18].

Among industrial crops and beverage-related industries, biorefinery approaches have been explored for various feedstocks to enhance sustainability and resource efficiency. For instance, in Australia, sugarcane residues are currently being investigated for their potential in sustainable aviation fuel production, demonstrating the capability of agricultural waste in bio-based industries[19]. Similarly, sugarcane bagasse, a fibrous by-product generated after juice extraction, has been extensively utilized in Brazil for bioethanol production, methane generation, and thermal energy recovery, further showcasing the efficiency of biorefinery processes in the sugar industry[20]. In the United States, switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), a perennial grass species, has been extensively investigated as a feedstock for cellulosic ethanol production. It has been reported to have a potential ethanol yield of up to 380 liters per tonne of harvested biomass[21]. In Spain, olive stones, a by-product of olive oil production, have been repurposed as an alternative energy source, replacing fossil fuels in heating systems, domestic boilers, and industrial machinery, thereby contributing to national decarbonization efforts[22]. The coffee industry generates significant amounts of agricultural waste, has also been an important area of study for biorefinery applications, particularly in utilizing spent coffee grounds (SCGs). SCGs contain lignocellulosic materials, lipids, and bioactive compounds, making them an attractive feedstock for multiple valorization pathways. A previous study has demonstrated SCGs' potential for biofuel production, including biodiesel, bioethanol, and biogas, with biodiesel yields reaching 80%–83% through in-situ transesterification[23]. Additionally, SCGs have been explored for their potential in producing biopolymers, antioxidants, and bio composites, showcasing a comprehensive biorefinery approach[23]. In another work, SCGs can be converted into multiple value-added products, including D-mannose, coffee oil, manno-oligosaccharides, and bioethanol which highlights the versatility of these agricultural residues in a biorefinery setting[24]. Nowadays, these advancements emphasize the feasibility of applying biorefinery principles to the coffee industry, aligning with the broader goal of optimizing biomass utilization through sustainable and efficient processing technologies. The continued development of these biorefinery approaches reinforces the need for integrating waste valorization strategies into agricultural supply chains, ultimately contributing to resource efficiency, and the reduction of environmental impacts associated with biomass waste disposal.

By utilizing a combination of technologies and processes, the biorefinery process aims to transform these abundant biological materials into valuable products[25]. The focus of the concepts are on the sustainable and effective use of the biomass. This involves using the best available technologies for all stages, like burning, breaking down, gas production, fermentation, and initial processing, within the biorefinery setup[26].

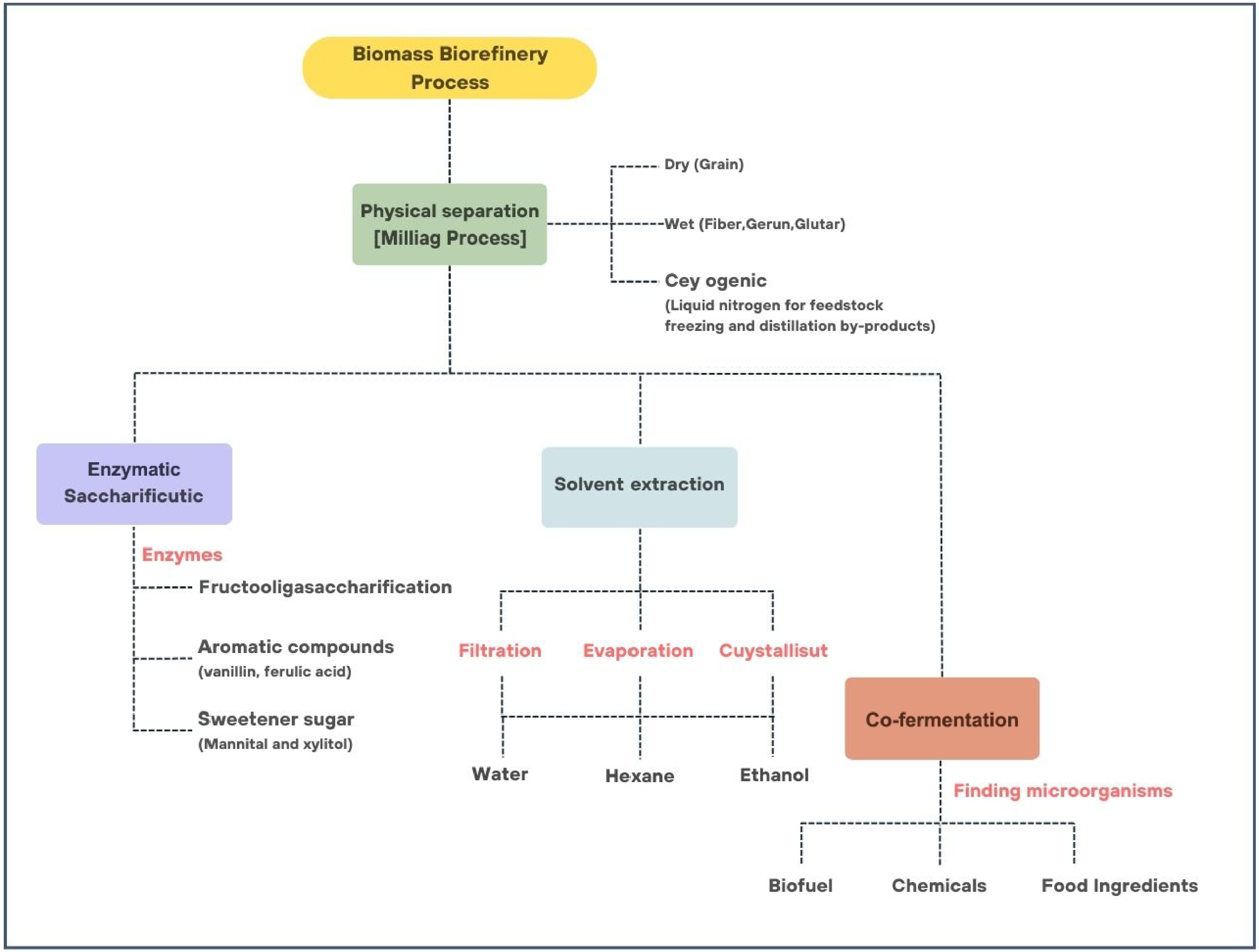

The successful development of biorefineries necessitates the incorporation of process engineering principles akin to those applied in crude oil refining[27]. Biorefinery processes can vary, and the number of processes involved depends on the specific type of biorefinery and the desired output, as shown in Fig. 1. Generally, the biorefinery incorporates a variety of biomass conversion processes to generate a variety of products, such as biochemicals, biofuels, and other bioproducts[28]. By integrating biorefinery processes, the coffee industry can enhance resource efficiency, mitigate environmental impact, and contribute to a circular bioeconomy, aligning with the BCG economic model. This approach not only addresses waste management challenges but also fosters economic opportunities by converting coffee pulp into high-value bio-based commodities, promoting sustainability across the entire coffee production chain[29]. The process of biorefinery usually involves these techniques.

Physical separations

-

The milling process plays a vital role in preparing biomass for conversion into valuable products in a biorefinery. By choosing the right milling method, and tailoring it to the specific feedstock and desired product, biorefineries can optimize their efficiency and profitability. Milling increases surface area, facilitating enzyme or chemical interaction, improves accessibility to valuable components like starch and cellulose, and reduces energy consumption in subsequent processing steps. Various types of milling processes, such as dry milling for grains, wet milling for wet feedstocks like sugarcane, and cryogenic milling using liquid nitrogen, cater to different feedstock characteristics. Choosing the right milling process depends on factors like the type of feedstock, desired final product, and the scale of operation. Large-scale biorefineries may prioritize high-throughput systems, while smaller operations may focus on cost-effectiveness[30,31]. Types of milling processes in the biorefineries, including wet milling, dry milling, and cryogenic milling. The wet milling process, which yields valuable co-products like fiber, germ, and gluten, involves pre-processing before ethanol fermentation, making it more resource-intensive. In the conventional dry milling process, the dried whole-crop material undergoes grinding, cooking, liquefaction, saccharification of starch using enzymes, yeast fermentation of sugars to ethanol, and subsequent distillation and ethanol dehydration. Cryogenic milling is a specialized method which uses liquid nitrogen to freeze the feedstock before grinding, which can preserve certain components and improve product yield. The by-products from distillation, distillers' dried grains (DDG) which are composed mainly of protein serve as animal feed[32]. This process takes advantage of the inherent physical properties of the ore, such as size, shape, color or light absorption, density, magnetic susceptibility, and electrical conductivity. It is widely utilized in the processing of industrial crops[33].

Enzymatic saccharification

-

Saccharification is the process of breaking down complex carbohydrates into simple sugars, is not just about unlocking the energy potential of biomass for biofuel production. While glucose, which serves as the main outcome of the saccharification process, drives the production of bioethanol, there are additional valuable components concealed within the plant cell walls, such as oligosaccharides, short-chain sugars with unique properties as prebiotics, dietary fiber, or sweeteners. Recent studies have showcased the efficacy of these techniques in recovering pharmaceutical ingredients. Khatun et al.[34] demonstrated the efficient recovery of fructo-oligosaccharides from sweet potatoes using enzymatic saccharification, while Messaoudi et al.[35] highlighted the valorization of sugarcane straw through saccharification, extracting valuable aromatic compounds such as vanillin or ferulic acid from plant cell walls. These aromatic compounds find applications in fragrances, pharmaceuticals, and bio-based materials. In addition, Bajpai[36] emphasized the potential of sugarcane bagasse as a source for mannitol production, through enzymatic saccharification and fermentation. Sugar derivatives like mannitol or xylitol, resulting from this process, possess desirable properties for use in food, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics.

Specific enzymes play an important role in this context. Envision employing enzymes tailored to target specific sugar chains or aromatic compounds[37]. Consider the integration of saccharification with additional extraction or purification methods, such as filtration or chromatography, as analogous to various sections of an orchestra collaborating harmoniously to enhance the precision and isolation of targeted components[38]. Enzymatic saccharification is pivotal in the coffee industry, facilitating the conversion of coffee by-products, including husks, pulp, and spent coffee grounds (SCG), into fermentable sugars via enzymatic hydrolysis. This process significantly enhances the valorization of coffee biomass, enabling the production of bioethanol, organic acids, and bioplastics, thereby contributing to a circular bioeconomy[39,40]. Furthermore, enzymatic hydrolysis improves the nutritional profile of coffee residues, enhancing digestibility for animal feed applications[41]. The fermentable sugars obtained from coffee waste also function as essential substrates for biodegradable polymers and bioplastics, promoting sustainable material production[42].

Solvent extraction

-

Solvent extraction holds a vital role in biorefineries, serving as a pivotal method for accessing valuable components beyond the reach of straightforward enzymatic processes like saccharification. Let's explore the intricacies of this procedure, unveiling its stages and applications[43−45]. The process initiates with the selection and preparation of the desired plant biomass. This may involve grinding, chipping, or other methods to enhance solvent penetration. Specific pre-treatment steps, such as soaking or washing, may be employed for optimal extraction efficiency. Choosing an appropriate solvent is critical for successful extraction, considering factors like selectivity, sustainability, compatibility, cost, and recovery. Green solvents derived from renewable sources are preferred for their environmental benefits.

The prepared biomass is introduced to the chosen solvent in a suitable reactor, employing techniques like soaking, percolation, or pressurized extraction to enhance efficiency. Post-extraction, separating the solvent containing the desired component from the biomass residue is essential. Common techniques include filtration, evaporation, and crystallization, with additional purification steps if higher purity is required. Solvent extraction is extensively applied within the coffee industry for the recovery of valuable compounds from coffee by-products, notably SCG and coffee husks. This technique facilitates the selective extraction of bioactive compounds, including caffeine, polyphenols, lipids, and antioxidants, utilizing organic solvents, which find applications in the food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic sectors[46]. For instance, hexane and ethanol are commonly employed to extract coffee oil from SCG, which can be subsequently refined for biodiesel production or incorporated into cosmetic formulations[47].

Co-fermentation

-

Co-fermentation, a key strategy in biorefineries, enables the simultaneous fermentation of various sugars in biomass, expanding the potential for producing biofuels, chemicals, and food ingredients. This process involves a coordinated effort among different microorganisms, each specialized in breaking down specific sugars to contribute to the final product. Unlike traditional fermentation strategies that mainly target glucose, co-fermentation utilizes a diverse group of microorganisms, including bacteria like Lactobacillus or Clostridium, and engineered yeast strains capable of fermenting a broader range of sugars. The fermentation symphony unfolds with pre-treatment processes breaking down complex carbohydrates, inoculation introducing the microorganism mixture, and simultaneous fermentation where each microorganism focuses on its preferred sugar. The result is the production of desired products, such as ethanol for biofuels, organic acids for chemicals, or specific food ingredients, depending on the chosen microorganisms and fermentation conditions. Co-fermentation enhances biomass utilization and overall product yield in biorefineries[48]. Co-fermentation in biorefineries brings advantages such as maximizing biomass use, boosting product yields, and allowing for diverse product creation. However, it also comes with challenges. Finding microorganisms that work well together is crucial, and optimizing the fermentation process is essential. Additionally, there may be extra costs and technical issues compared to traditional methods. Overall, while co-fermentation offers great potential, overcoming these challenges is important for successful implementation in biorefineries[49].

Bioethanol, an alternative fuel for engines, is generated via the fermentation of sugars derived from hydrolyzed cellulosic substances. To improve ethanol production efficiency, an advanced fermentation method called Simultaneous Saccharification and Co-fermentation (SSCF) is utilized[50]. This advanced method, nearing commercialization, focuses on continuous improvement for achieving high ethanol concentration, utilizing total sugars (hexose + pentose), reducing feedback inhibition, optimizing mass transfer, and implementing one-pot conversion strategies. The study analyzed key enhancement tactics, such as expediting saccharification rates, genetically modifying bacteria for co-fermentation, optimizing mass transfer via impeller design, and investigating the influence of conditional factors in the SSCF process. Co-fermentation represents an innovative approach within the coffee industry because this process is particularly advantageous for the production of bioethanol, organic acids, and microbial bioplastics from coffee pulp, husks, and SCG[39]. By employing combined microbial consortia, such as yeasts and bacteria, co-fermentation facilitates more efficient sugar utilization, augments metabolite production, and minimizes inhibitory by-products that may impede fermentation[51,52]. For instance, this approach supports the development of functional food products, such as fermented coffee-based beverages enriched with probiotics[53]. By integrating co-fermentation into comprehensive biorefinery processes, the coffee industry can optimize waste valorization and improve biotech efficiency[54,55].

-

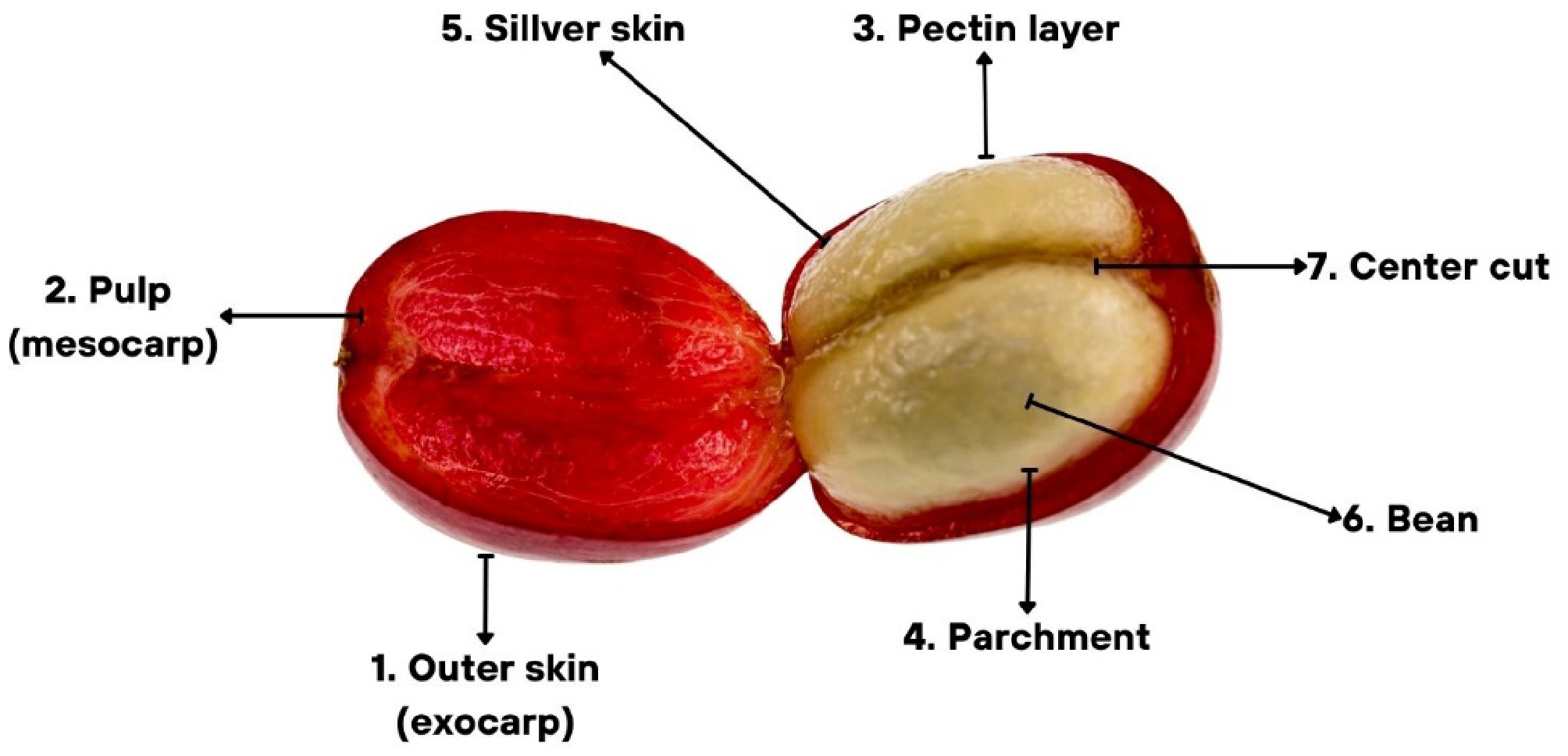

Coffee (Coffea spp.), an internationally traded commodity, plays a vital role in the agricultural sectors of Africa, Asia, and the Americas, with an annual production of over 10.5 million tonnes, rendering it the second-largest commercial commodity after gasoline[56,57]. The tropical genus Coffea, belonging to the Rubiaceae family, primarily originates from the highlands of Ethiopia and South Sudan. Within the expansive genus Coffea, encompassing at least 125 species, two species stand out for their economic significance in coffee production namely C. arabica L. (Arabica coffee), and C. canephora (Robusta coffee). Arabica coffee, a self-fertile tetraploid, exhibits notably low genetic diversity, a factor that underscores its importance in the global coffee industry[58], commanding a premium price and contributing approximately 60%–65% to the total coffee production[11]. The coffee cherry, comprising skin, pulp, parchment, silver skin, bean, and embryo, constitutes the fruit, and the tree's open branching system and self-fertilizing flowers contribute to its distinctive reproductive biology[59].

Coffee processing

-

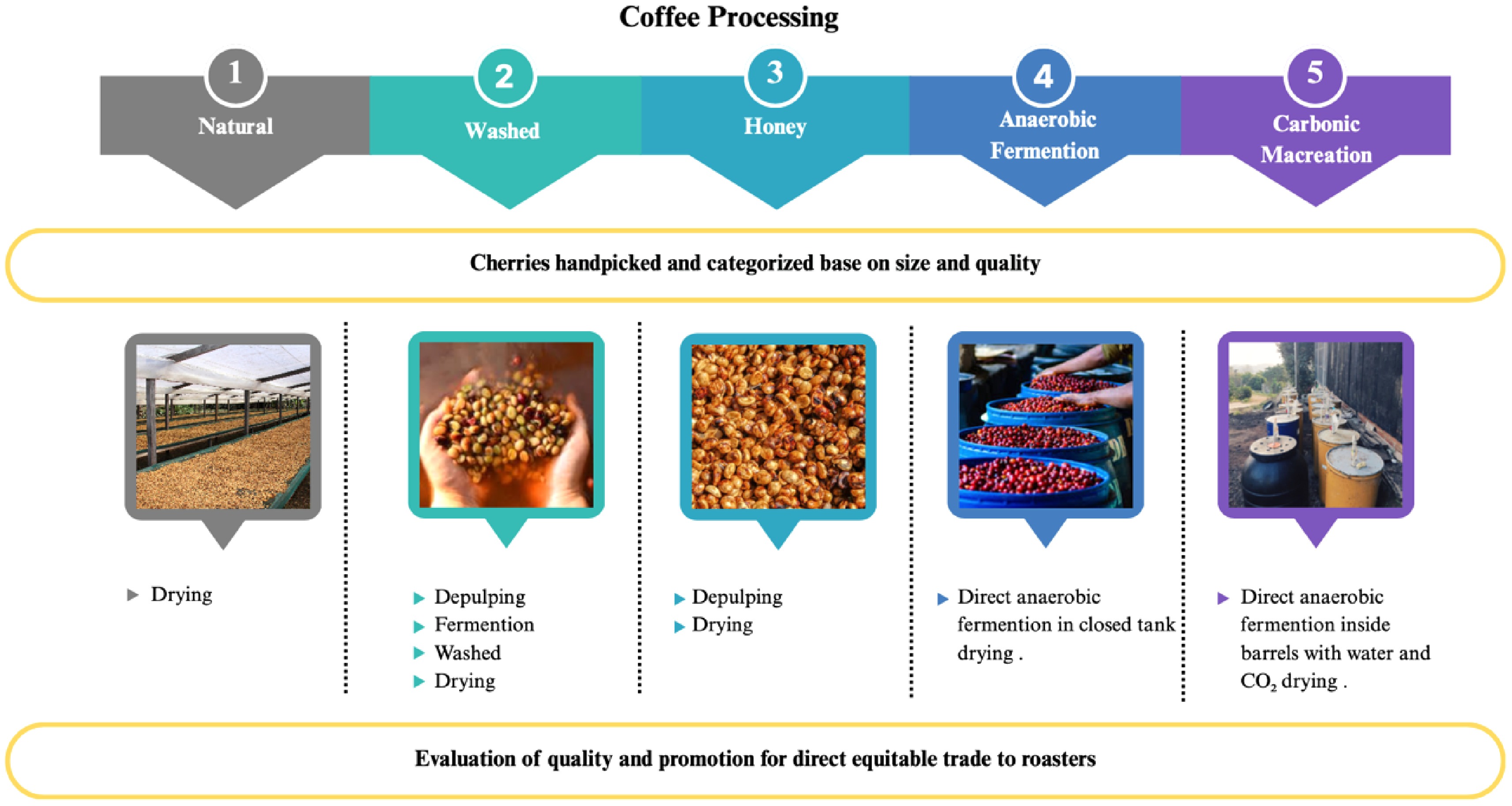

Processing of coffee is a critical factor in determining its quality and flavor within the complex realm of coffee. The intricate sequence of procedures that culminate in the ultimate gustatory encounter for coffee consumers comprises the following: harvesting, de-pulping, fermentation, washing, drying, milling, sorting, grading, roasting, grinding, and brewing[60]. The foundation is established by pruning, which is accomplished by selectively selecting ripe cherries for collection. Fermentation decomposes mucilage, while depulping removes the outer skin. In the context of coffee beans, the flavor and quality are significantly impacted by the processing techniques employed. These processes, which fall into classifications such as 'fully washed', 'dry natural', 'pulped natural', and 'wet hulled', aim to eliminate mucilage and regulate moisture content[61]. Different techniques impart unique qualities to the final product, ranging from the sun-drenched 'natural' method to the water-associated 'pulped natural', 'honey', and 'fully washed' approaches as presented in Fig. 2. Further complicating the quality discourse are the complex interrelationships among washing and fermentation, mucilage, and bacterial dynamics. Every processing technique significantly influences the flavor, acidity, and overall profile of the coffee. For instance, the 'honey' method imparts a nuanced mucilage level, while the washed/fully washed-wet process involves meticulous steps. The vast array of processing techniques employed highlights the intrinsic connection that coffee connoisseurs have with their sensory experience.

Coffee biomass

-

Despite its economic prominence, the coffee sector faces challenges associated with substantial biological losses during processing, accounting for up to 40%–45% of the coffee fruit, including pulp, parchment, silver skin, and spent coffee grounds as illustrated in Fig. 3[5]. Among the by-products generated in coffee processing, coffee pulp emerges as a substantial biological waste, accounting for up to 29% of the total dried weight[62]. Regrettably, improper disposal practices pose environmental risks, water quality, and jeopardize soil[63]. However, specific places acknowledge the inherent potential of coffee pulp as a valued asset. Innovative techniques, such as its application as fertilizer or as an energy source via direct burning, biogases, and feedstock, underscore the versatility of this waste material[57,64,65]. Boasting a rich composition of proteins, carbohydrates, fats, fibers, and antioxidants such as epicatechin, chlorogenic acid, phenolic compounds, and caffeine[66−68], coffee pulp presents a promising avenue for sustainable resource management.

Value-added components from coffee pulp

-

Efforts have been invested in valorizing coffee pulp biomass due to its abundance and cost-effectiveness. Studies emphasize the recovery of bioactive components, showcasing the potential for creating biodegradable composites[69−71]. By-products from coffee processing constitute more than 50% of the dry weight of the coffee fruit[5]; there exists a substantial opportunity to transform this perceived 'waste' into valuable bioactives. Coffee pulp, abundant in polysaccharides such as pectin, cellulose, and hemicellulose which presents potential for various applications in the food and cosmetics industries[41]. The inclusion of phenolic components, including chlorogenic acid, epicatechin, and caffeine, amplifies its worth[66−68]. Fueled by environmental challenges and the quest for sustainable alternatives, interest has surged in utilizing coffee pulp for creating biodegradable composites and extracting bioactive components[66−71].

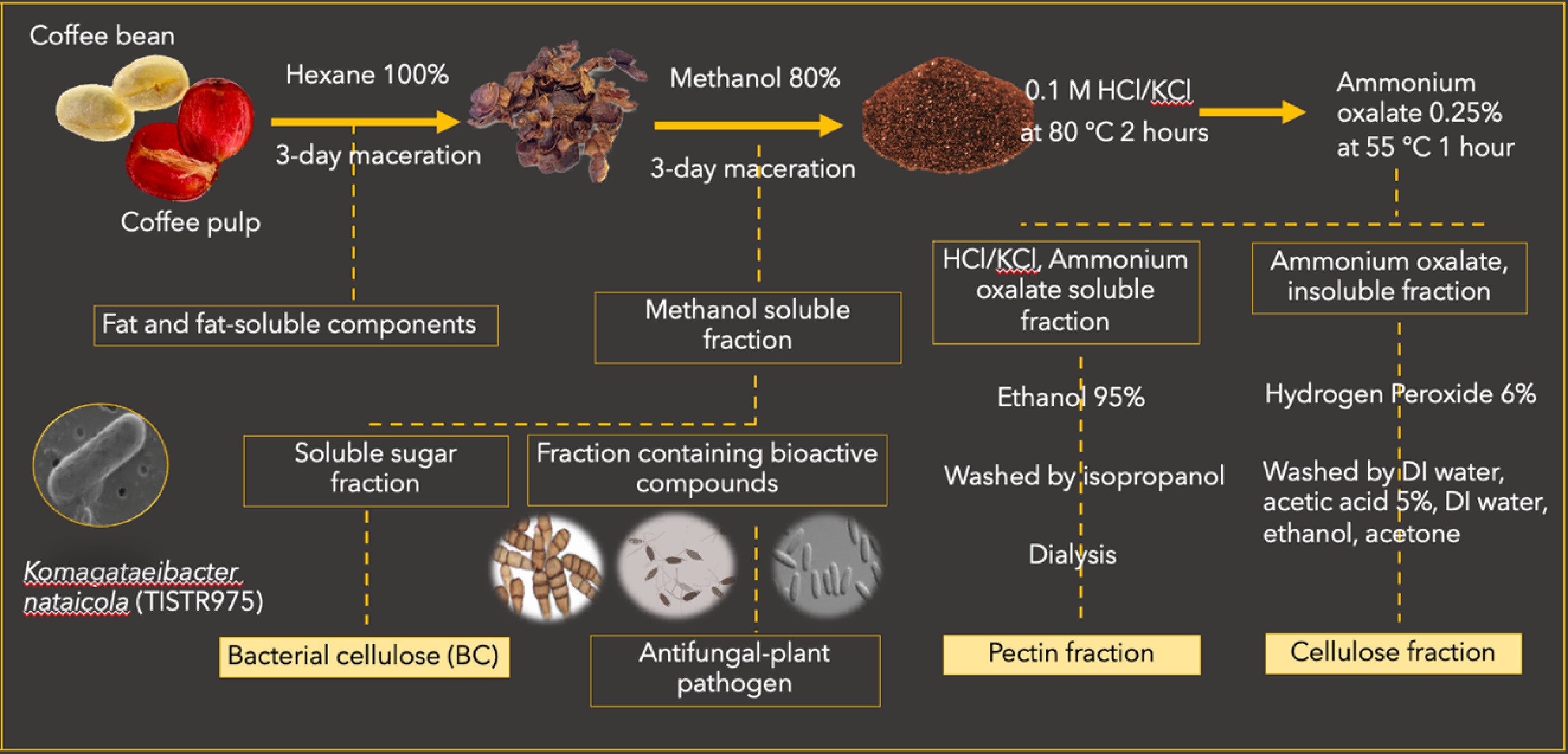

Recent studies have spotlighted coffee cherry pulp as a source of antioxidants, colorants, and phenolic chemicals, prompting exploration in pharmaceuticals and cosmetics[72]. Moreover, the water-soluble lignocellulosic fraction derived from coffee waste has potential applications in bioethanol production[73,74]. Coffee pulp has found utility in diverse food products, from coffee pulp juice to cascara and kombucha cascara[75]. Numerous studies on value-added components extracted from coffee pulp exist, including Sommano et al., who investigated a sequential maceration technique utilizing organic solvents, effectively obtaining valuable components from coffee pulp that constituted around 13% of the entire extract. This fraction, predominantly composed of fat-soluble chemicals, was acquired using dichloromethane and ethanol extraction. Coffee pulp analysis revealed a significant polysaccharide content (approximately 60%), present in both soluble and insoluble forms. Pectin extraction commenced with HCl/KCl and ammonium oxalate buffers. The acidic pH (2.0) of the HCl/KCl buffer facilitated pectin solubilization by disrupting ionic and hydrogen bonds, while subsequent ammonium oxalate treatment enhanced extraction via calcium ion complexation. Cellulose was identified as the primary component, comprising up to 40% of the pulp. Bleaching with H2O2 and NaBH4 was employed to remove lignin and residues, yielding a white composite and aiming for improved extraction efficiency. A separate study utilizing alkali treatment and distilled water bleaching extracted cellulose microfibrils as a highly hydrated white gel (approximately 20% concentration)[76]. The observed variability in the visual properties of these cellulosic materials suggests a requirement for more detailed characterization, as shown in Fig. 4. These initiatives seamlessly align with the broader bio-circular economic goal, highlighting the comprehensive usage of biomass resources in environmentally friendly and economically successful ways. The transformative journey from coffee waste to valuable resources stands as a testament to the industry's commitment to sustainability and innovation.

Proximal composition of coffee pulp

-

Coffee pulp, an often-overlooked by-product of coffee processing, holds a wealth of nutritional components that contribute to its proximal composition. This fleshy residue, extracted from the coffee cherry during the initial stages of production, undergoes dynamic variations influenced by factors like the coffee varieties (e.g., Arabica, Robusta), agricultural practices (e.g., fertilization, soil type), and processing techniques (e.g., wet, dry)[77]. Understanding the nutritional makeup of coffee pulp is essential not only for its prospective applications but also for promoting sustainable practices in the coffee business.

At its core, coffee pulp is characterized by a high moisture content, typically around 80%[78,79], setting it apart as the succulent counterpart to the coffee bean. Carbohydrates dominate its composition (~60%), dominated by dietary fiber (15%–25%) and sugars (~7%), contributing to energy intake and gut health[69,80,81]. The protein level may reach 9%; the inclusion of this macronutrient enhances the nutritional diversity of the pulp[11]. Additionally, the lipid content is notably low, primarily consisting of healthier unsaturated fats[11]. Rich in minerals such as potassium, phosphorus, calcium, and magnesium, coffee pulp embodies a complex matrix of nutrients[82].

Coffee pulp polysaccharides

-

Coffee pulp polysaccharides, comprising a diverse group of complex carbohydrates, are integral components found in the pulp of coffee cherries. The structural makeup of these polysaccharides, including cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin, exhibits variation influenced by elements such as coffee cultivar, environmental conditions, and processing techniques[83]. Notably, the potential health benefits associated with coffee pulp polysaccharides are noteworthy, with certain components, like dietary fiber, contributing to digestive health, and supporting the proliferation of beneficial gut bacteria[80]. Beyond health implications, coffee pulp polysaccharides are of interest in biotechnological applications, prompting exploration into their extraction for the development of bioactive compounds with pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and food industry applications. For instance, in the study of Sommano et al.[76], the cellulose extracted from coffee pulp is hereafter referred to as coffee pulp cellulose (CPC). This abbreviation is employed to distinguish it from cellulose derived from other lignocellulosic sources, and to emphasize its unique origin from coffee pulp biomass. CPC was successfully extracted from Arabica coffee pulp produced during wet processing, demonstrating potential industrial applications. The process involved sequential extraction steps and resulted in structurally damaged CPC with lignin and hemicellulose presence. Hydrogels were produced using CPC, alginate, and pectin, showing varying swelling and durability based on CPC concentration. Importantly, all hydrogel formulations demonstrated no toxicity towards HaCaT cells (human keratinocyte cells), indicating potential use in wound healing applications.

Coffee pulp polyphenols

-

Coffee pulp polyphenols constitute a group of naturally occurring compounds with antioxidant properties that are inherent in the pulp of coffee cherries. These plant-derived micronutrients, including chlorogenic acids, flavonoids, and other phenolic compounds, contribute to the antioxidant richness of the coffee cherry[63]. The composition of coffee pulp polyphenols varies depending on factors such as coffee variety, cherry ripeness, and processing methods[84,85]. Beyond the well-established presence of polyphenols in coffee beans, attention is increasingly directed towards the polyphenols in coffee pulp for their antifungal applications[11, 86,87].

The antioxidant properties of coffee pulp polyphenols play a crucial role in neutralizing free radicals, suggesting potential health-promoting effects[11,63,67]. Moreover, coffee pulp, as a byproduct of coffee processing, offers an avenue for sustainable practices. Extracting polyphenols from coffee pulp not only adds value to the byproduct but also aligns with efforts to reduce waste and foster a circular economy in the coffee industry[11,62,88].

Specialized extraction techniques, including solvent extraction, chromatography, and other separation methods, are employed to obtain high-quality polyphenol extracts from coffee pulp[84,85,89]. Researchers are actively exploring the optimization of these extraction processes for various applications. Coffee pulp polyphenols hold promise for diverse uses, ranging from enhancing the nutritional content of functional foods to the development of dietary supplements and pharmaceuticals[85].

-

Coffee pulp constitutes 40% to 50% of the coffee berry's weight, and is the primary by-product from coffee processing. Currently treated as waste in much of the industry, it poses significant environmental challenges, impacting flora and fauna, water and soil, and causing issues for nearby communities due to odor and insect proliferation. This review examines the diverse applications of coffee pulp in agriculture, medical, food and nutrition, and biotechnology. In agriculture, it can serve as organic fertilizer, contribute to biological plant pathogen control, and function as feed for various animals. In biotechnology, coffee pulp finds application in cultivating edible fungi, producing enzymes, and serving as a substrate for microorganisms involved in caffeine degradation and natural fungicide production. While many applications have been proposed and studied, emerging uses include utilizing pulp bioactive compounds for food supplements, enhancing dietary fiber content in consumables, and producing environmentally friendly biobased containers and biopackaging as alternatives to plastics. The sample of applications are illustrated in Table 1.

Food, medical, and pharmaceutical production

-

Instances of capitalizing on the advantages inherent in value-added constituents derived from coffee pulp for applications in food, medical, and pharmaceutical industries, encompassing chlorogenic acid, protocatechuic acid, gallic acid, rutin, and dietary fiber. These components serve as integral elements in the beverages, dedicated to elevating fresh for consumers[72]. Moreover, Anthocyanin (Cyanidin-3-rutinoside) was utilized as a food colorant, and it has been found to have significant potential as an economic source of natural pigments[90]. Furthermore, pectin from coffee pulp was used as anantibacterial film, and the results show that the pectin film, composed of coffee pectin combined with commercial apple pectin, shows antimicrobial action against Staphylococcus aureus TISTR 1466[91]. Pectin-microcrystalline cellulose, chlorogenic acid, and cellulose from coffee pulp were utilized in the creation of biofilms, serving as edible films for food packaging, antimicrobial, and antioxidant-enhanced food packaging, as well as applications in the biomedical and pharmaceutical sectors. The outcomes were deemed satisfactory, with biopolymer films derived from combinations of microcrystalline cellulose and coffee pectin exhibiting a sleek surface, high clarity, and notable tensile strength. Additionally, these films showcased antimicrobial attributes and antioxidant properties, making them suitable for the manufacturing of food packaging and versatile enough for applications in biomedical and pharmaceutical fields[76,92,93]. A widely favored beverage infusion is Cascara tea, crafted from the husks of coffee cherries, prominent in the beverage industry. Notably, it contains polyphenols, characterized by their antioxidative attributes and their role in regulating various physiological functions to uphold normalcy within the body[94], and the cascara tea was analyzed for sensory evaluation and shelf-life stability for microbiological and physicochemical properties.

Bioethanol production

-

In the study conducted by Menezes et al.[74], the utilization of coffee pulp for bioethanol production was investigated using the reducing sugar refining process, identified as the most effective extraction method. The results demonstrated that coffee pulp extract, when combined with sugarcane juice or molasses, the result shown that the yield approximately 70 g/L in batch fermentations conducted at 30 °C for 24 h.

Dye/chemical production

-

The utilization of coffee pulp in the chemical production industry involves extracting cellulose to produce cellulose microfibrils (CMFs). Adsorption studies indicated that equilibrium was reached within 90 min. Kinetic data exhibited a strong fit to the pseudo-second-order model, while the Freundlich isotherm model accurately described the adsorption behavior. This research demonstrates a potential approach to valorize coffee pulp waste, a readily available, cost-effective, and renewable byproduct of the coffee processing industry, rich in cellulose. Consequently, the extracted cellulose microfibrils (CMFs) present a promising avenue for the development of sustainable and economically viable bio-sourced materials, contributing to the future progress of cellulose utilization in advanced applications[95].

Feeding of animals

-

The animal feed production industry has incorporated value-added components derived from coffee pulp, such as extracted sugars, into various applications, including aquaculture feed. A feeding trial conducted on Oreochromis aureus fingerlings assessed the efficacy of bacteria-treated coffee pulp (BT-CoP) in their diets. The study concluded that O. aureus fingerlings can tolerate the inclusion of small quantities of BT-CoP without exhibiting negative impacts on growth performance and feed utilization parameters. Notably, diets containing coffee pulp did not compromise fish survival (100%), and any observed reduction in tilapia performance is likely attributable to the elevated fiber content present in the coffee pulp-based diets[96]. The applicable uses of value adding components from the coffee pulp are listed as in Table 1.

Table 1. Biorefinery applications of the value adding components from the coffee pulp.

Industry Product Major compounds Purpose of application Ref. Food, medical, and pharmaceutical production Beverage Chlorogenic acid Bioactive enrichment [72] Protocatechuic acid, gallic acid Rutin Dietary fiber Food colorant Anthocyanin

(cyanidin-3-rutinoside)Significant potential as an economic source of natural pigments [90,97] Antibacterial film Pectin Antibacterial film for biomedical and pharmaceutical fields [91] Biofilm Pectin-microcrystalline cellulose Edible film for food packaging [92] Chlorogenic acid Antimicrobial and antioxidant food packaging [93] Cellulose Biomedical and pharmaceutical fields [76,98] Cascara tea Polyphenols Bioactive enrichment [94] Bioethanol production Ethanol Sugar Sugar utilisation and using less water during the fermentation process [74] Dye/chemical production Novel highly hydrated cellulose microfibrils Cellulose Dyes removal from industrial wastewater [95] Feeding of animals Fish diets Sugar Effectiveness of bacteria treated-coffee pulp in fish diets [96] Various substrates Lignocellulosic Bio-circular approach for sustainability [99] -

In alignment with the BCG policy, there has been continuous development in biorefining processes aimed at recovering unused biomasses generated during food industrial processing. Biorefineries were characterized by the principles of green chemistry and clean technologies, and play a pivotal role in elevating the value of residual biomass. This is achieved by fostering the production of biofuels and bioproducts with high added value, thereby contributing significantly to the advancement of the bio-economy[100,101]. Historically, biorefining processes predominantly focused on biofuels, particularly bioethanol and biobutanol, primarily driven by the escalating prices of crude oil. However, the contemporary approach to biorefining endeavors encompasses the extraction of natural products. Unlike the initial emphasis on fuels, the current objectives extend to various downstream industries. Biomass from processing, characterized by a substantial volume, has attracted attention in this regard[102]. Consequently, there is a growing interest in utilizing green technology, biorefining, and circular economy principles to reclaim valuable bioproducts.

A diverse range of biomass sources is abundant in secondary metabolites and structural biopolymers, which can be extracted and converted into high-value compounds, including pectin, pectic oligosaccharides, phenolic compounds, carotenoids, and dietary fiber. These compounds have widespread applications across the medical, pharmaceutical, food, nutraceutical, and cosmetics sectors. Beyond the generation of economic value from biomass, the principles of the circular economy, underpinned by 'zero waste' technologies, promote a positive environmental impact by prioritizing the reuse, recycling, and recovery of these by-products[103]. The concept of zero waste revolves around minimizing waste by eliminating systems that generate waste, aligning society with zero waste technologies. This entails adopting second-generation biorefinery methods and ensuring the broad distribution of consumer goods obtained through clean processing. Following the integration of these products into society, the encouragement of reusing, recycling, and recovering valuable components is facilitated using advanced recovery technologies. This comprehensive approach not only supports environmental sustainability but also brings about overall economic advantages by promoting collaboration between producers and consumers, thereby contributing to the enhancement of biological diversity[104,105].

-

The future of the coffee industry relies on the advancement of biorefinery strategies that align with sustainability goals and circular economy principles. As global demand for eco-friendly products and renewable resources increases, further research is needed to optimize the conversion of coffee pulp into high-value bio-based commodities[106]. One promising direction is the development of advanced enzymatic and microbial technologies to improve the efficiency of biochemical conversion processes, such as enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation[39,107]. Research on genetically engineered microorganisms could enhance bioethanol production and organic acid synthesis, making the coffee biorefinery process more cost-effective[69].

Another key area is the expansion of bio-based materials derived from coffee residues, such as bioplastics, biochar, and composite materials for packaging and industrial applications. The amalgamation of nanotechnology and green chemistry methodologies may result in the creation of superior biomaterials characterized by improved durability and biodegradability[108,109]. Furthermore, solvent-free extraction methods and green processing technologies, such as supercritical fluid extraction, should be explored to maximize the recovery of bioactive compounds from coffee waste while minimizing environmental impact[11,110].

Future research should also address policy frameworks and economic incentives to support the commercialization of coffee-based bioproducts. Collaboration between academia, industry, and policymakers is essential to create scalable and economically viable solutions that promote resource efficiency and sustainable innovation in the coffee sector[111]. By integrating emerging technologies, circular economy models, and policy-driven strategies, the coffee industry can transition towards a more resilient, low-waste, and economically sustainable future.

-

This study highlights the role of biorefinery approaches in fostering sustainability within the coffee industry, aligning with circular economy principles. Adopting biochemical, thermochemical, and physicochemical conversion processes can significantly enhance waste management and resource efficiency. Furthermore, integrating renewable energy systems and waste-to-energy technologies in coffee biorefineries can contribute to reducing environmental impacts and enhancing energy sustainability within the industry. The development of green extraction techniques and advanced processes offers promising prospects for improving biochemical recovery while minimizing chemical usage and waste generation. Additionally, the adoption of circular economy principles, supported by policy frameworks and industry collaboration, will be crucial for scaling up biorefinery operations and ensuring long-term sustainability. Future research should concentrate on optimizing bioprocessing processes, enhancing process efficiency, and creating creative applications for coffee-derived bioproducts. variables such as coffee cultivar. Strengthening interdisciplinary cooperation between researchers, industry stakeholders, and policymakers will be essential for accelerating technological advancements and facilitating commercialization. By embracing biorefinery innovations and circular economy models, the coffee industry can transition towards a low-waste, resource-efficient, and environmentally responsible future, ultimately contributing to a more sustainable global bioeconomy.

This research work was partially supported by Chiang Mai University and the CMU Proactive Researcher Program, Chiang Mai University.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: investigation: Sangta J, Wongkaew M, Tangpao T; formal analysis: Sangta J, Hongsibsong S, Sringarm K; validation, writing original draft, visualization: Sangta J; writing, review and editing: Rachtanapun P, Hongsibsong S, Sringarm K, Sommano SR; conceptualisation, supervision: Sommano SR. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Not applicable.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Sangta J, Wongkaew M, Hongsibsong S, Sringarm K, Tangpao T, et al. 2025. Value-added strategies for coffee biomass: advancing biorefinery approaches within the bio-circular-green economy for resource efficiency and environmental sustainability. Circular Agricultural Systems 5: e016 doi: 10.48130/cas-0025-0013

Value-added strategies for coffee biomass: advancing biorefinery approaches within the bio-circular-green economy for resource efficiency and environmental sustainability

- Received: 22 April 2025

- Revised: 08 October 2025

- Accepted: 11 October 2025

- Published online: 29 December 2025

Abstract: The coffee industry produces a considerable quantity of biomass residue, with coffee pulp representing a particularly prevalent by-product. Inadequate management of coffee pulp disposal contributes to significant environmental concerns. However, biorefinery approaches offer a sustainable solution by converting this agro-industrial waste into high-value bio-based products, aligning with the principles of the Bio-Circular-Green (BCG) economy. This review comprehensively examines biorefinery processes applicable to coffee biomass, including extraction, enzymatic hydrolysis, fermentation, and thermochemical conversion. These processes are applied to produce biofuels, organic acids, bioplastics, biofertilizers, and functional compounds. The study highlights the potential of circular economy strategies in optimizing waste valorization, promoting resource efficiency, and minimizing environmental impact through the integration of green technology and renewable resources. Furthermore, this review identifies research gaps and proposes future directions for advancing industrial applications and scientific innovation in coffee pulp utilization. This work serves as a valuable resource for researchers, industry stakeholders, and policymakers aiming to cultivate a circular and sustainable bioeconomy within the coffee industry by providing a perspective on the sustainable transformation of coffee pulp into high-value commodities.

-

Key words:

- Applications /

- Bio-circular approaches /

- By-products /

- Industry processing /

- Renewable resources