-

Biomass, characterized by its carbon neutrality, renewability, and widespread availability, is a sustainable and environmentally friendly raw material for the production of fuels and chemicals[1−3]. Pyrolysis is an important thermal conversion approach capable of effectively converting biomass into bio-oil[4,5]. The targeted regulation of the pyrolysis reaction enables the selective enrichment of specific high-value compounds in bio-oil, which remains a global research hotspot[6,7].

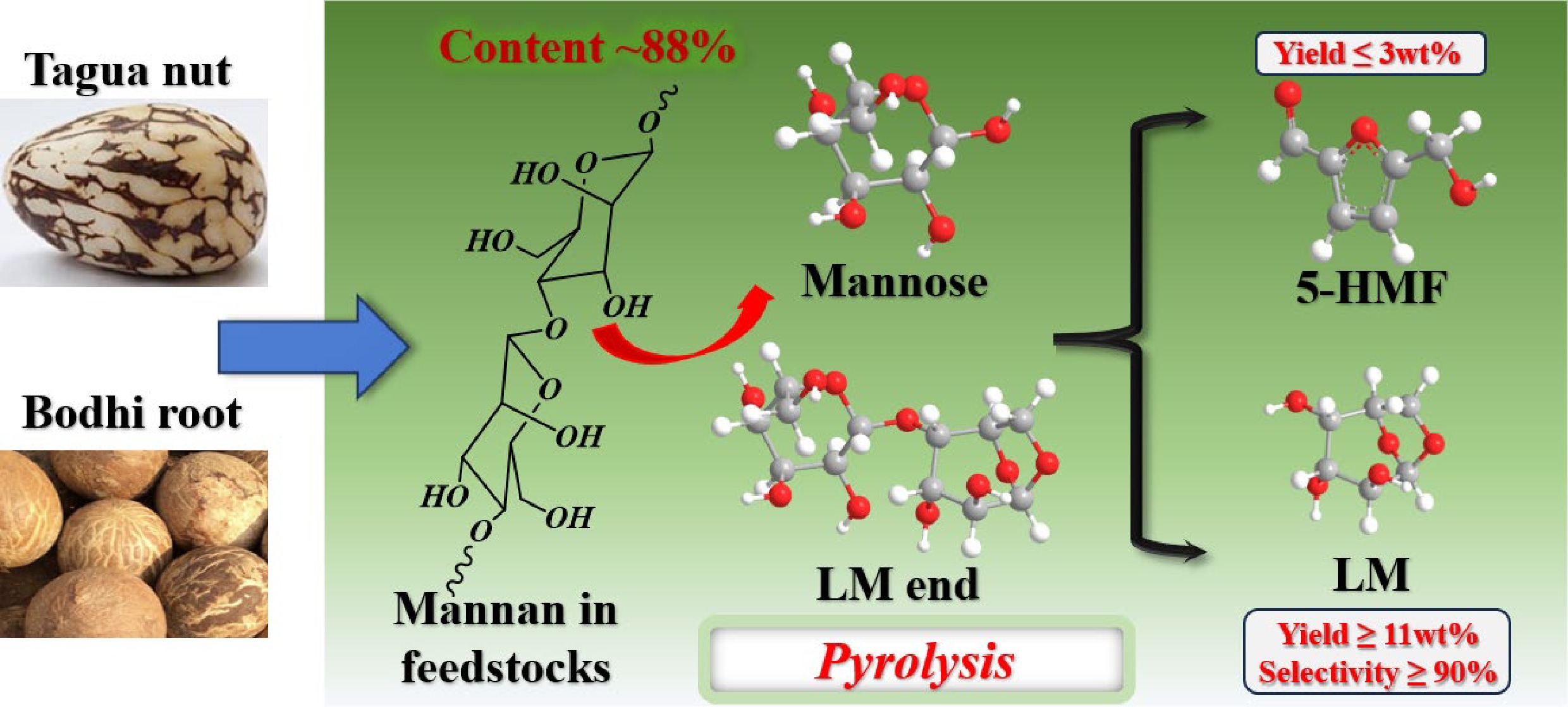

The processing wastes generated from handicraft production represent a typical form of biomass resource, and the efficient management of these wastes has become increasingly urgent in light of the rapid expansion of the handicraft processing industry[8]. Palm plants, such as the tagua nut, bodhi root, coconut shell, and peach palm fruits, serve as important raw materials for handicraft manufacturing. These materials predominantly consist of palm seeds characterized by a high holocellulose content alongside relatively low levels of lignin and ash[9]. Therefore, these palm-derived processing residues exhibit considerable potential to be converted into value-added anhydrosugar or furan derivatives through fast pyrolysis[10]. For example, tagua nut, which is primarily composed of mannan hemicellulose, can be converted into levomannosan (LM) and 5-hydroxymethyl-furfural (5-HMF) by direct fast pyrolysis[11,12]. Ghysels et al.[13] further demonstrated that tagua nut could be converted into levoglucosenone (LGO) or furfural (FF), with yields reaching 6.64 wt% and 13.17 wt%, respectively, when catalyzed by H3PO4 or ZnCl2 during pyrolysis. Sangthong et al.[14] found that lignin extracted from palm kernel shells yielded a higher bio-oil yield than the raw palm kernel shells during pyrolysis. Particularly, the total content of phenolic compounds in the bio-oil from the extracted lignin was approximately twice that from the raw palm kernel shells.

In recent years, the pyrolysis of palm-based handicraft wastes has attracted increasing attention. However, the fundamental structural properties and pyrolysis reaction mechanisms of these materials remain insufficiently understood, thereby constraining the advancement of efficient pyrolysis methods to produce high-value products. Herein, two commonly used handicraft materials from South America (tagua nut) and Asia (bodhi root) were employed as representative feedstocks to explore their structural and pyrolytic characteristics. Initially, the physical morphology and chemical composition of the raw materials were characterized. Subsequently, thermogravimetry-infrared spectroscopy (TG-FTIR) and in-situ diffuse reflectance Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (in-situ DRIFT) were employed to elucidate the thermal weight loss patterns and the evolution of solid and liquid phase products during pyrolysis. Furthermore, pyrolysis-gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (Py-GC/MS) was used for online analysis, complemented by offline detection using a horizontal fixed-bed reactor to examine the distribution of liquid products. Finally, the correlation among the feedstock structure, pyrolysis reactions, and products was analyzed. The findings of the present work are expected to provide a theoretical foundation for the selective pyrolysis of palm-based handicraft wastes, facilitating the production of value-added chemicals.

-

Tagua nuts (originating from Ecuador) used in the experiment were purchased from Jining Xingxin Trading Company, and bodhi roots (originating from Myanmar) were purchased from Yueming Fine Products Company. The original samples of tagua nuts and bodhi roots were first dried in a laboratory oven at 105 °C for 48 h. Then, the dried samples were crushed, screened, and sieved, and the particles with a size of less than 0.25 mm were retained for subsequent experiments. Ethanol (99.9%) and LM (99%) were purchased from Macklin, FF (99%) was purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry, and 5-HMF (98%) was purchased from Aladdin.

Characterization of feedstocks

-

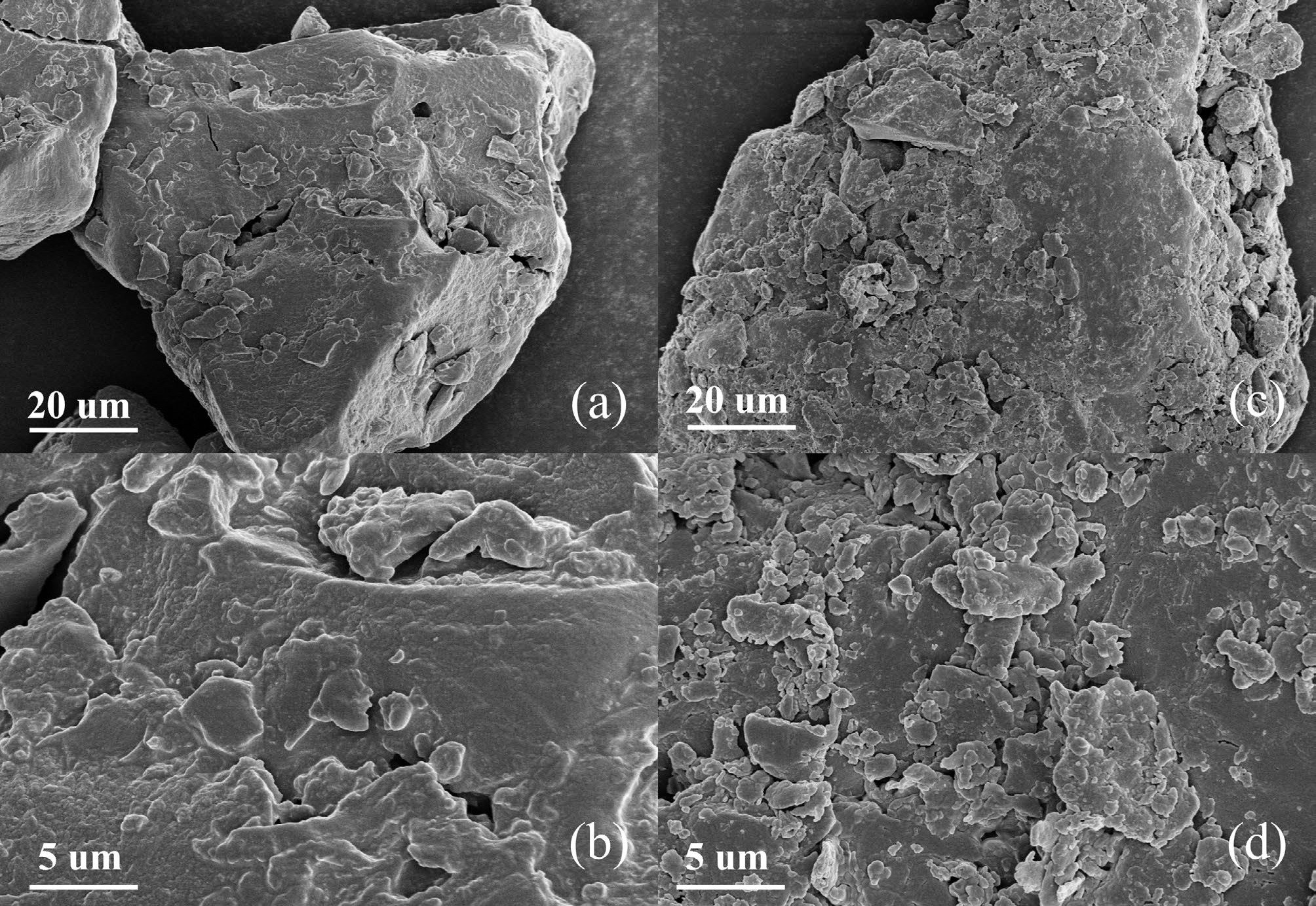

Proximate analysis of tagua nuts and bodhi roots was carried out in a muffle furnace (DC-B-1) according to the standard GB/T212-2008. Ultimate analysis for CHONS of the two raw materials was conducted utilizing a Vario MACRO Cube elemental analyzer. Concentrations of Al, Ca, Fe, K, Mg, Na, and Si in the samples were quantified via an ICPOSE730 inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES) manufactured by Agilent, USA. The microstructures of the samples were characterized by a Hitachi SU8020 field emission scanning electron microscope (SEM), operating at 3.0 kV, with a working distance of 4.4 mm, and a resolution of 50 μm.

To determine the holocellulose and lignin contents, the Van Soest washing method was employed, leveraging the differential solubility of components in specific reagents[15,16]. The composition of the holocellulose was further determined by a modified hydrolysis procedure, wherein the raw materials were hydrolyzed by using 72% H2SO4 in a water bath at 30 °C for 1 h, followed by dilution to 4%. Monosaccharide constituents in the resulting hydrolysate were identified and quantified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, Agilent U3000) to determine the fundamental structural units of holocellulose in both tagua nuts and bodhi roots. Protein content was assessed by measuring nitrogen levels via the Kjeldahl method[17,18]. The Soxhlet extraction method was used to test the fat content in the raw materials, based on the principles of solvent reflux and siphoning[19,20]. Pectin content was quantified using the carbazole colorimetric assay, based on the hydrolysis of pectin into galacturonic acid and its subsequent condensation reaction with the carbazole reagent.

TG-FTIR

-

The TG-FTIR experiments were conducted using a STA600 thermogravimetric analyzer (TA Instruments) and a Nicolet 20 Fourier transform infrared spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific) to study the weight loss characteristics of the raw materials and the real-time evolution of the pyrolysis volatiles. For each experiment, 10 mg of the sample was heated gradually from 50 to 800 °C, with a fixed heating rate of 10 °C/min. The nitrogen flow rate was set at 20 mL/min, and the pressure was 3.0 bar. The volatiles flowed into the infrared spectrophotometer through a transfer line (270 °C). The resolution of the infrared spectrometer was set at 4 cm−1, and the spectral scanning region was 600–4,000 cm−1.

In-situ DRIFT

-

The in-situ DRIFT analysis of tagua nut and bodhi root samples was carried out using a Spectrum 100 FTIR spectrometer (Perkin Elmer) and a ZnSe window-based chamber (Specac) to observe the evolution of solid-phase functional groups at different pyrolysis temperatures. The spectrum of 100 mg potassium bromide powder at room temperature was used as the scanning background. A mixture of 1 mg sample with 100 mg potassium bromide was tested at 150, 200, 250, 300, 350, 400, 450, and 500 °C under a nitrogen flow (100 mL/min). The scan was repeated 16 times, the wavenumber range was 4,000–650 cm−1, and the resolution was 4 cm−1.

Py-GC/MS experiments

-

The Py-GC/MS experiments were conducted using a pyrolyzer (CDS 6150HP), a gas chromatograph (HP8860 series, Agilent), and a mass spectrometer (HP5977B MSD, Agilent). A quantity of 0.20 mg of the raw material was used and pyrolyzed at 300, 400, 500, 600, and 700 °C. Other specific parameters or conditions can be found in our previous work[21]. The yields of the main products were determined by the external standard method, and the product selectivity was evaluated by the percentage of the peak area.

Lab scale fixed-bed pyrolysis experiments

-

The lab scale horizontal fixed-bed pyrolysis device was mainly composed of a tubular resistance furnace, a quartz tube reactor (inner diameter 10 cm), a nitrogen cylinder, and a condenser[22]. In each operation, air in the reactor was first removed with nitrogen. Subsequently, the nitrogen flow rate was maintained at 60 mL/min to ensure an inert atmosphere for pyrolysis. After the furnace temperature reached and stabilized at the preset temperature, 2 g of the sample loaded into a quartz boat was sent to the constant temperature zone of the reactor and maintained for 10 min. The bio-oil was collected by liquid nitrogen condensation. Ethanol was used to wash, collect, and dilute the liquid products. The yields of liquid and solid products were obtained by weighing, and the yield of gas product was calculated by the difference subtraction method. GC/MS was used to analyze the main organic components of the liquid products, and the external standard method was adopted to quantify the yields of the main products in the pyrolysis experiment. A Karl Fischer moisture analyzer was used to determine the moisture content. Each of the above experiments was carried out three times to confirm the reliability of the experiments.

-

Table 1 presents the results of the ultimate and proximate analyses. The elemental compositions of tagua nut (C: 41.47 ± 0.08 wt%; N: 1.83 wt%; H: 6.59 ± 0.02 wt%) and bodhi root (C: 44.87 ± 0.38 wt%; N: 1.14 ± 0.01 wt%; H: 6.76 wt%) were comparable, indicating their carbohydrate-rich nature. Upon storage at 105 °C for a week, both raw materials turned brown, attributed to the Maillard reaction between protein and carbohydrate in the raw materials. This observation suggests that N likely exists in the form of a bound protein within the feedstocks.

Table 1. The proximate analysis and ultimate analysis of tagua and bodhi roots

Sample Tagua Bodhi root Ultimate analysis (wt%) C 41.47 ± 0.08 44.87 ± 0.38 N 1.83 ± 0.00 1.14 ± 0.01 H 6.59 ± 0.02 6.76 ± 0.01 S 0.46 ± 0.06 0.34 ± 0.02 O* 49.65 ± 0.16 46.9 ± 0.40 Proximate analysis (wt%) Moisture 7.44 ± 0.04 3.32 ± 0.28 Ash 1.10 ± 0.01 2.62 ± 0.13 Volatile 76.78 ± 0.50 84.28 ± 0.11 Fix carbon 14.68 ± 0.54 9.79 ± 0.51 * Calculated by the difference. In terms of proximate analysis, tagua nut demonstrated higher fixed carbon content (14.68 ± 0.54 wt%) and moisture content (7.44 ± 0.04 wt%) relative to bodhi root. Conversely, bodhi root exhibited greater volatile matter (84.28 ± 0.11 wt%) and ash content (3.32 ± 0.28 wt%) compared to tagua nut. Overall, the volatile matter content in both raw materials exceeded that typically observed in conventional lignocellulosic biomass from agriculture and forestry wastes. This elevated volatile content is attributable to the relatively high content of carbohydrates (i.e., holocellulose) present in these materials[23−25], as corroborated by subsequent chemical composition analyses. Generally, a high volatile content is associated with an increased mass loss rate and enhanced bio-oil yield, which was further substantiated by the pyrolysis experiments detailed in Sections 'TG-FTIR results' and 'Lab-scale fixed bed pyrolysis results'.

The ash content in tagua nut and bodhi root was relatively lower than that observed in common biomass materials[26]. According to Table 2, K accounted for the highest proportion among the ash components in both feedstocks. Notably, the concentrations of all detected ash constituents in bodhi root exceeded those found in tagua nut. Ash, particularly alkali and alkaline earth metals, is known to catalyze the secondary cracking of volatile matter into non-condensable gases[27]. Hence, the bodhi root pyrolysis was expected to yield more gases, which was confirmed in Section 'Lab-scale fixed bed pyrolysis results'.

Table 2. The ash content of tagua nut and bodhi root

Ash Tagua nut (g/kg) Bodhi root (g/kg) Ca 0.0491 0.0653 Fe 0.0025 0.0198 Mg 0.0398 0.1079 Si 0.0068 0.0319 K 0.2929 0.3229 Na 0.0033 0.0122 The component analysis results for tagua nut and bodhi root are summarized in Tables 3 and 4. The holocellulose content of tagua nut was determined to be 92.8 wt%, while the lignin content was relatively low, merely 2.5 wt%. For the bodhi root, it exhibited a holocellulose content of 86.8 wt% and a lignin content of 4 wt%. According to Table 4, mannose was identified as the principal monosaccharide in the hydrolysate of both tagua nut and bodhi root, with relative peak areas of 87.59% and 88.01%, respectively. These findings aligned with the reported results, confirming that the main component of tagua nut was mannan-type hemicellulose[28].

Table 3. Chemical compositions of tagua nut and bodhi root

Sample Tagua nut (wt%) Bodhi root (wt%) Holocellulose 92.80 86.80 Lignin 2.50 4.00 Protein 3.85 4.64 Fat 4.37 6.34 Pectin 2.90 4.42 Table 4. HPLC analysis of the hydrolysate of tagua nut and bodhi root

Sample Tagua nut (%) Bodhi root (%) Mannose 87.59 88.01 Ribose 0.40 0.38 Glucuronic acid 2.08 2.34 Galacturonic acid 0.30 0.27 Glucose 3.39 2.39 Galactose 2.73 4.39 Xylose 1.35 0.13 Arabinose 2.14 2.06 Fucose 0.02 0.03 The SEM results of the raw material powders are shown in Fig. 1. Bodhi root exhibited a rough surface, whereas tagua nut showed a relatively smooth surface. This is because the tagua nut has a harder texture than the bodhi root. Specifically, the hard texture enabled the tagua nut to form a smooth cross-section more easily during the grinding process. As a result, the relatively rough surface of the bodhi root provided a larger specific surface area, which was beneficial for the subsequent pyrolysis.

TG-FTIR results

-

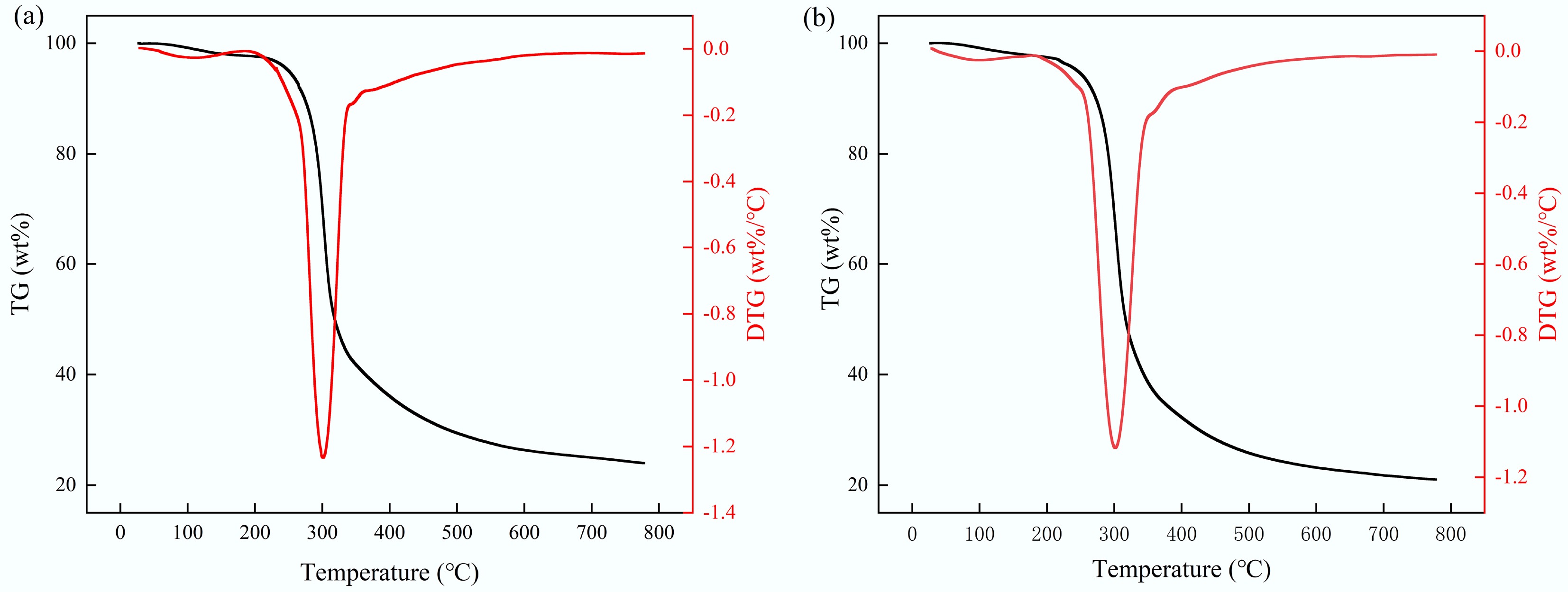

Figure 2 illustrates the thermogravimetric (TG) and derivative thermogravimetric (DTG) curves of tagua nut and bodhi root samples subjected to heating from 20 to 800 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min under a nitrogen atmosphere. The weight loss characteristics of these materials markedly differed from those observed in typical lignocellulosic biomass raw materials (e.g., straw, sawdust), primarily due to their predominant composition of mannan-type hemicellulose, as detailed in Tables 3 and 4. The DTG curves revealed that the pyrolysis of tagua nut and bodhi root proceeded through three distinct stages. The initial stage, spanning 20 to 180 °C, corresponded mainly to the evaporation of free moisture. The second stage (180 to 380 °C) represented the rapid pyrolysis stage, during which mannan-type hemicellulose underwent depolymerization, dehydration, and other decomposition reactions. Concurrently, a large amount of volatiles was released, leading to significant weight loss. The highest weight loss rates of tagua nut and bodhi root were observed at 301 and 302 °C, respectively. The weight loss peak temperatures were relatively higher than those reported for xylan-type hemicellulose (~268 °C) but lower than the typical decomposition temperature of cellulose (~350 °C)[29,30], corroborating the predominance of mannan in these materials. The final stage, from 380 to 800 °C, was characterized by carbonization, evidenced by a reduced weight loss rate and the formation of biochar. At 800 °C, the residual mass of tagua nut (24 wt%) exceeded that of bodhi root (21 wt%), consistent with the proximate analysis results indicating a higher fixed carbon content and lower volatile content in tagua nut.

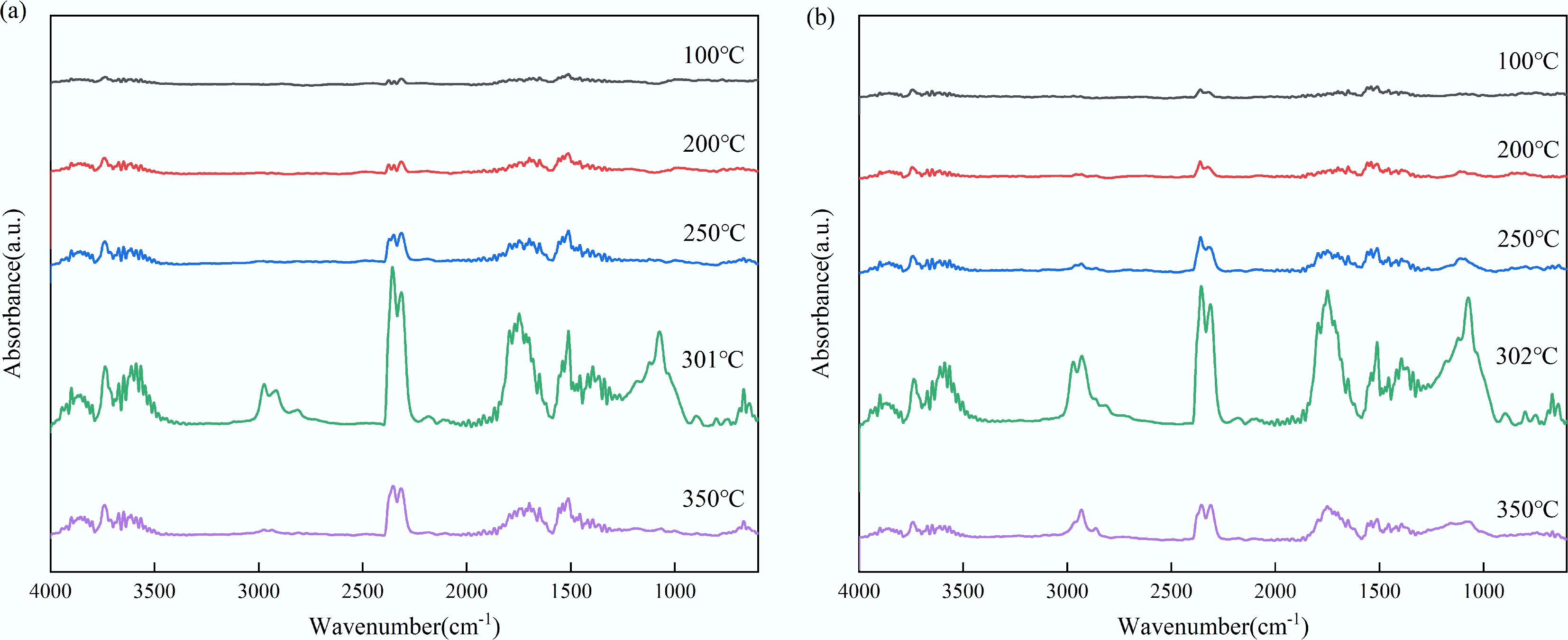

The FTIR spectra of the volatiles from tagua nut and bodhi root are shown in Fig. 3. Below 200 °C, there was no obvious volatile release, except for slight O–H stretching at 3,445–3,620 cm–1, indicative of moisture evaporation. As the pyrolysis temperature rose, numerous volatile compounds containing carbonyl groups (e.g., aldehydes and ketones) and CO2 (2,400–2,240 cm–1) were generated. At the maximum weight loss temperature, the OH vibration peak at 3,800–3,500 cm−1 mainly originated from the dehydration reactions. The C–H stretching vibrations in the range of 3,000–2,800 cm–1 originated from the presence of methyl and methylene groups[31]. The peaks at 2,400–2,240 and 750–600 cm–1 indicated that the carbonyl groups in biomass raw materials were broken and CO2 was generated through the decarboxylation process. The absorption band at 1,786–1,730 cm−1 was assigned to carbonyl compounds (e.g., carboxylic acids and aldehydes), while the vibration at 2,230–2,030 cm−1 suggested CO formation from the C–O bond cleavage in alcohols or ethers. The peaks at 1,500–1,000 cm−1 characterized the existence of in-plane bending vibration of C–H, C–O, and C–C skeleton vibrations. Among them, the 1,060–1,000 cm–1 band was assigned to the formation of CH3OH[32]. At the maximum weight loss temperature, the absorbance of the above functional groups increased by two to six times. With further increase in pyrolysis temperature, the absorbance gradually decreased owing to the intense decomposition of the raw materials.

In-situ DRIFT results

-

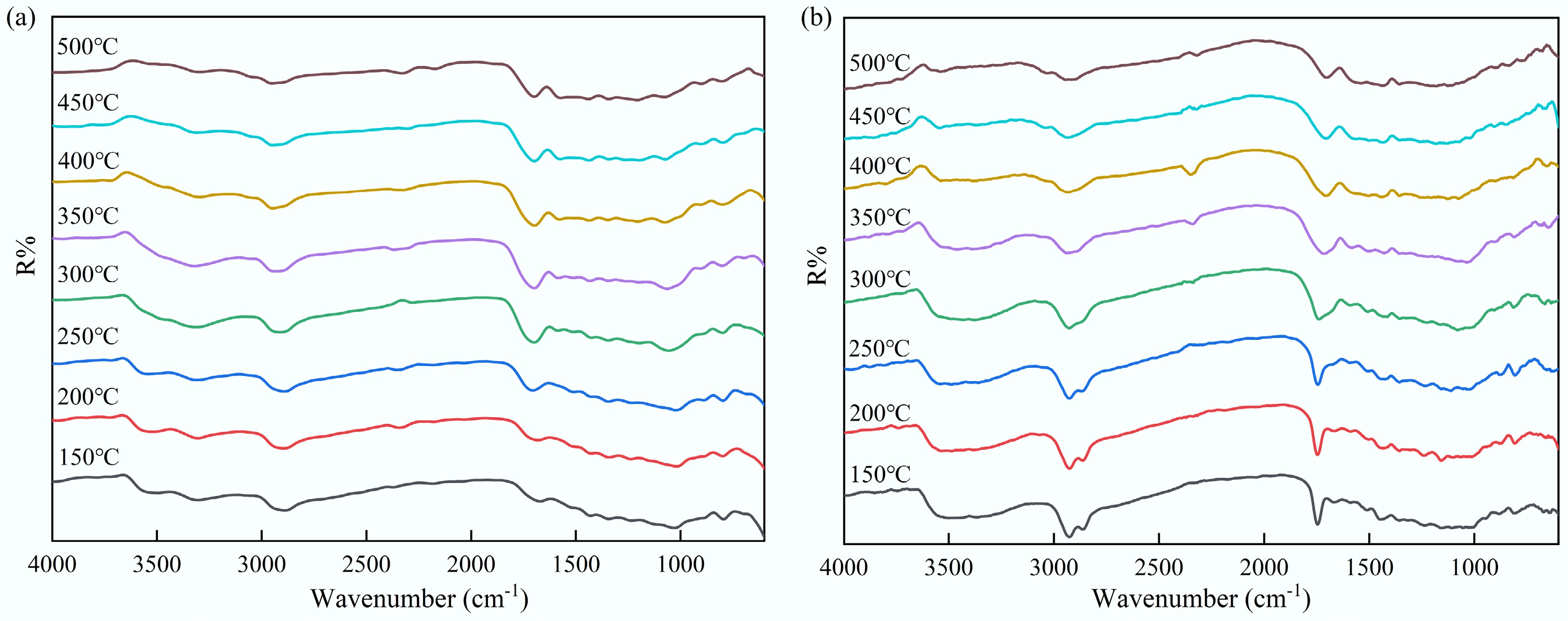

The in-situ DRIFT experiment was employed to characterize the structural transformation occurring in the solid phase during the slow pyrolysis of feedstocks. Figure 4 presents the in-situ DRIFT spectra of the pyrolysis of tagua nut and bodhi root over a temperature range of 150 to 500 °C. Below 250 °C, the spectra profiles of both materials were largely similar. However, at 450 °C, the vibration peaks corresponding to the principal functional groups disappeared. This observation aligned with the TG-FTIR results, which identified the primary weight loss interval for both feedstocks to be between 180 and 380 °C. These findings indicated that the decomposition of the functional groups in the solid phase was directly associated with the weight loss observed during pyrolysis. In addition, although the residual functional groups continued to evolve beyond 400 °C, the generation of volatile products was comparatively limited.

According to Fig. 4, the –OH absorption bands in the range of 3,200–3,700 cm–1 for both tagua nut and bodhi root exhibited a marked decrease at approximately 350 °C, indicating the substantial disruption of the hydrogen bonds and the elimination of hydroxyl groups with increasing temperature[33]. Concurrently, the C–H peak intensities at 2,916 cm−1 (tagua nut) and 2,936 cm−1 (bodhi root) gradually decreased, possibly due to the degradation of aliphatic side chains and aromatic structures. As the temperature rose, the intensity of the C=O stretching peak at 1,704 cm–1 in tagua nut progressively increased at 250 °C, which might be attributed to the formation of carbonyl compounds. In contrast, the intensity of non-conjugated C=O in bodhi root diminished as the temperature approached 300 °C, accompanied by a shift in the vibration peak from 1,749 to 1,704 cm–1. This shift was potentially indicative of the elimination reaction of hydroxyl groups and the cleavage of C-C bonds.

Py-GC/MS results

-

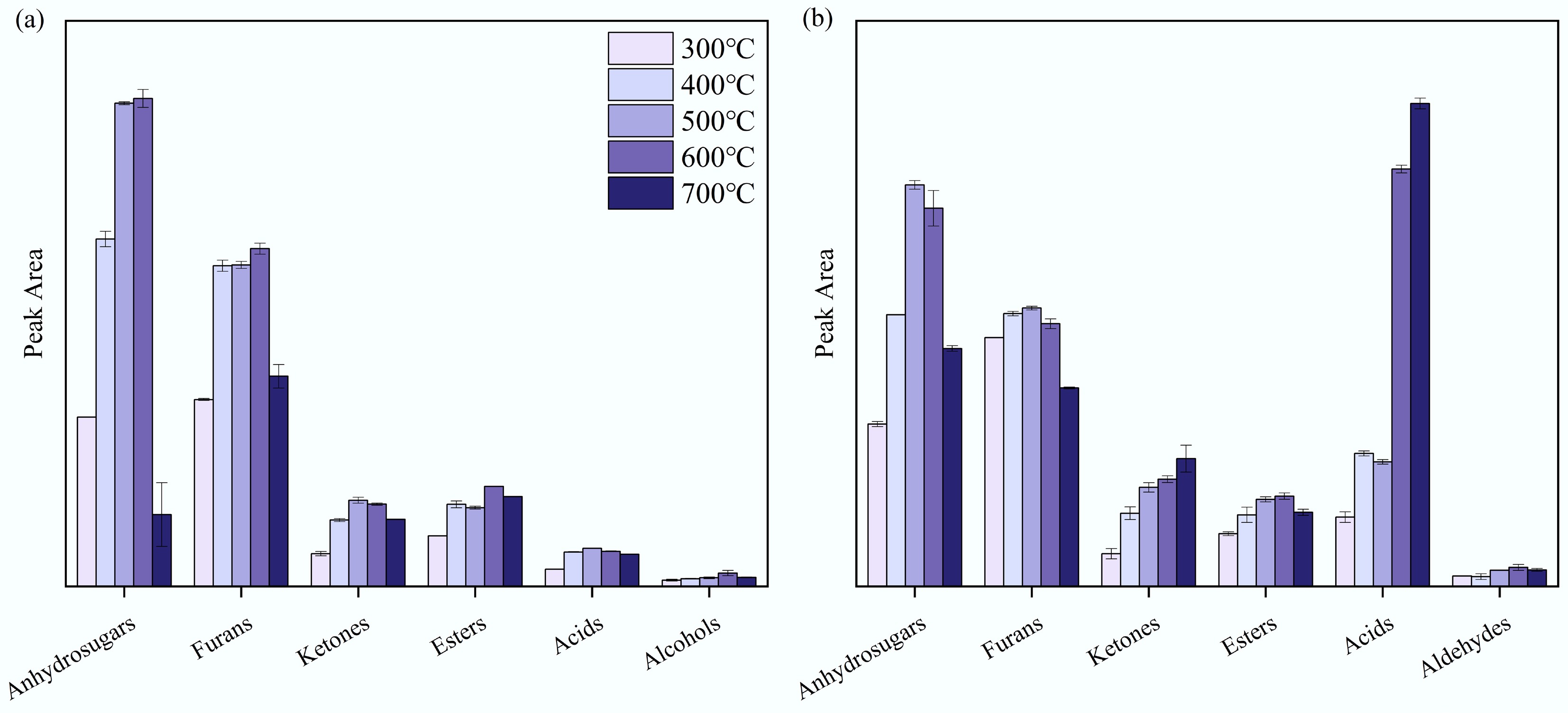

The product distribution from the pyrolysis of tagua nut and bodhi root was investigated using the Py-GC/MS experiments. The ion chromatograms of the pyrolysis products obtained at different temperatures are presented in Supplementary Fig. S1, and all the detected products are summarized in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2. These products were classified into anhydrosugars, furans, ketones, esters, acids, and aldehydes.

As illustrated in Fig. 5, the pyrolysis of tagua nut yielded higher peak areas for anhydrosugars and furans. For all five kinds of products, the peak areas exhibited an initial increase followed by a decline as the temperature rose. The maximum peak area was observed at around 500–600 °C, with anhydrosugars and furans predominating. Within the anhydrosugar fraction, LM was the principal component, accounting for over 90% of the anhydrosugar peak area at 500 °C. The primary furan derivatives identified were 5-HMF and FF, which represented 45% and 16% of the furan peak area at 600 °C. These findings were consistent with the fact that the main component of tagua nut was mannan (Table 4). Similar results have also been reported by Ghysels et al.[13]. Notably, when heated above 400 °C, the bodhi root could produce dodecanoic acid. This might be due to the higher fat content in the bodhi root compared to the tagua nut, as the fat undergoes dehydration and condensation during high-temperature pyrolysis, resulting in the formation of dodecanoic acid.

Similarly, the pyrolysis products of bodhi root exhibited a trend where their peak areas increased up to 600 °C, before decreasing at higher temperatures. Anhydrosugars and furan compounds dominated as pyrolysis products across both low and high temperature ranges. Among anhydrosugars, LM accounted for 95% of the peak area at 500 °C. The primary furan derivatives were 5-HMF and FF, which made up 47% and 21% of the furan peak area at 600 °C, respectively. Notably, the peak area of dodecanoic acid gradually increased with rising pyrolysis temperature, eventually becoming one of the main products.

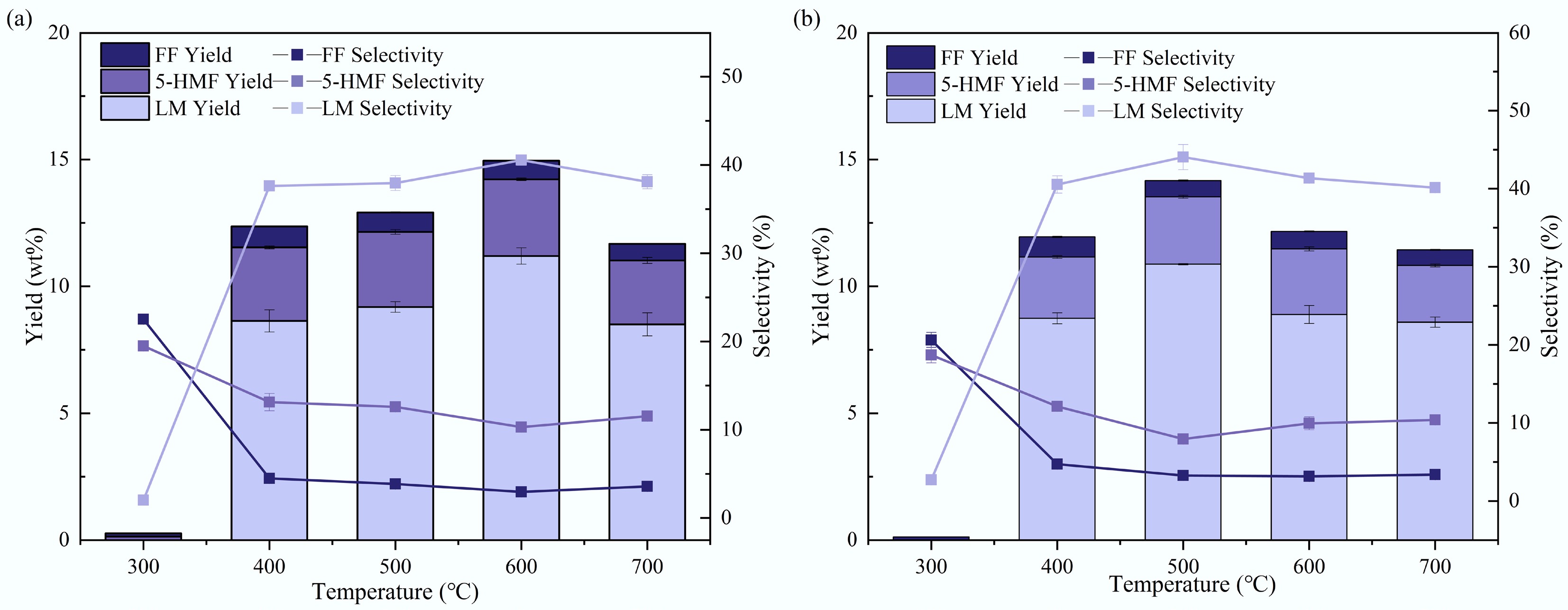

The yields and selectivity of these major products are shown in Fig. 6. At 300 °C, there are almost no pyrolysis products, so the selectivity has no practical significance. When the temperature reaches 400 °C, a large number of pyrolysis products begin to appear, and their total yield shows a trend of increasing first and then decreasing as the temperature rises from 400 to 700 °C. Further temperature increases had little influence on the product distribution.

Figure 6.

Yields and selectivities of main pyrolysis products for (a) tagua nut and (b) bodhi roots in Py-GC/MS experiments.

For tagua nut pyrolysis, the LM yield first exhibited a rapid increase and then decreased as the pyrolysis temperature rose, reaching a maximum of 11.2 wt% at 600 °C, with the corresponding selectivity of 40.5%. The 5-HMF yield showed an obvious increase from 300 to 400 °C, and remained stable as the temperature rose. The maximum 5-HMF yield was 3.0 wt% (600 °C), with the corresponding selectivity of 10.3%. The overall yield of FF was relatively low, reaching a maximum of 0.8 wt% at 400 °C with a corresponding selectivity of 4.5%. Bodhi root pyrolysis products exhibited similar trends. In contrast, both LM and 5-HMF peaked at 500 °C, with maximum yields of 10.9 wt% and 2.7 wt%, respectively, and corresponding selectivities of 44.0% and 8.0%. Notably, although both tagua nut and bodhi root are primarily composed of mannan, the pyrolysis temperatures for maximum LM yields differed. This discrepancy could be attributed to variations in their compositional characteristics and ash contents.

Lab-scale fixed-bed pyrolysis results

-

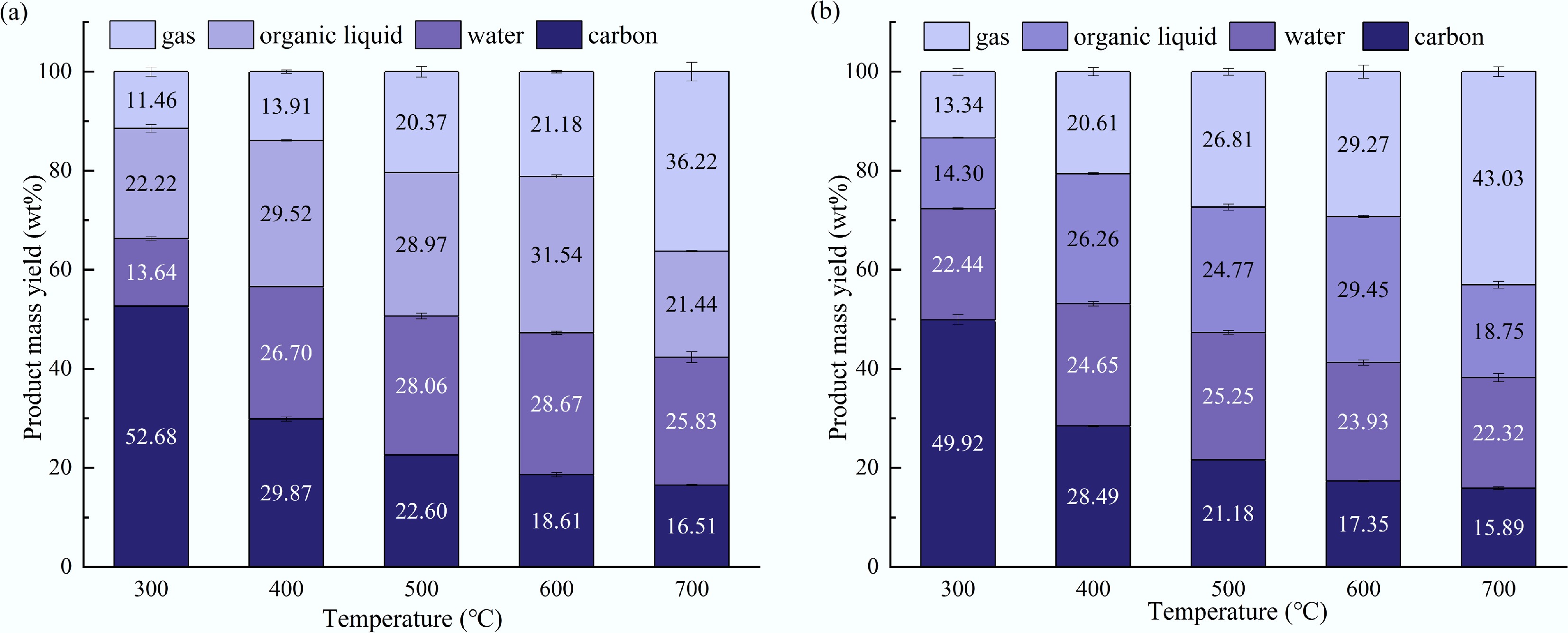

A horizontal fixed bed was employed to conduct the lab-scale pyrolysis experiments. Figure 7 compares the yields of solid, liquid, and gas products at different temperatures. The variation trends of pyrolysis gas and solid char were opposite, with the former showing an increasing tendency with increasing temperature. Specifically, during the entire pyrolysis process, the char yield gradually decreased, while the gas yield gradually increased. In the temperature range of 300–600 °C, the yield of liquid products first increased with the increase of temperature and then decreased. This was because higher temperatures promoted the pyrolysis of tagua nuts, thereby enhancing the yields of liquid and gas products. However, an excessively high temperature would cause the decomposition of bio-oil, consequently increasing the yield of pyrolysis gas. Throughout the pyrolysis temperature range, it was found that the maximum pyrolysis oil yield of tagua nuts was obtained at 600 °C, reaching 60.2 wt%, while that for bodhi roots also peaked at 600 °C with 53.4 wt%. In addition, the water content of the bio-oil was determined using a Karl Fischer moisture titrator. It is found that the overall water content in pyrolysis oil first increased and then decreased with increasing temperature.

Figure 7.

Yields of the solid, liquid, and gas products from the lab-scale pyrolysis of (a) tagua nut and (b) bodhi root.

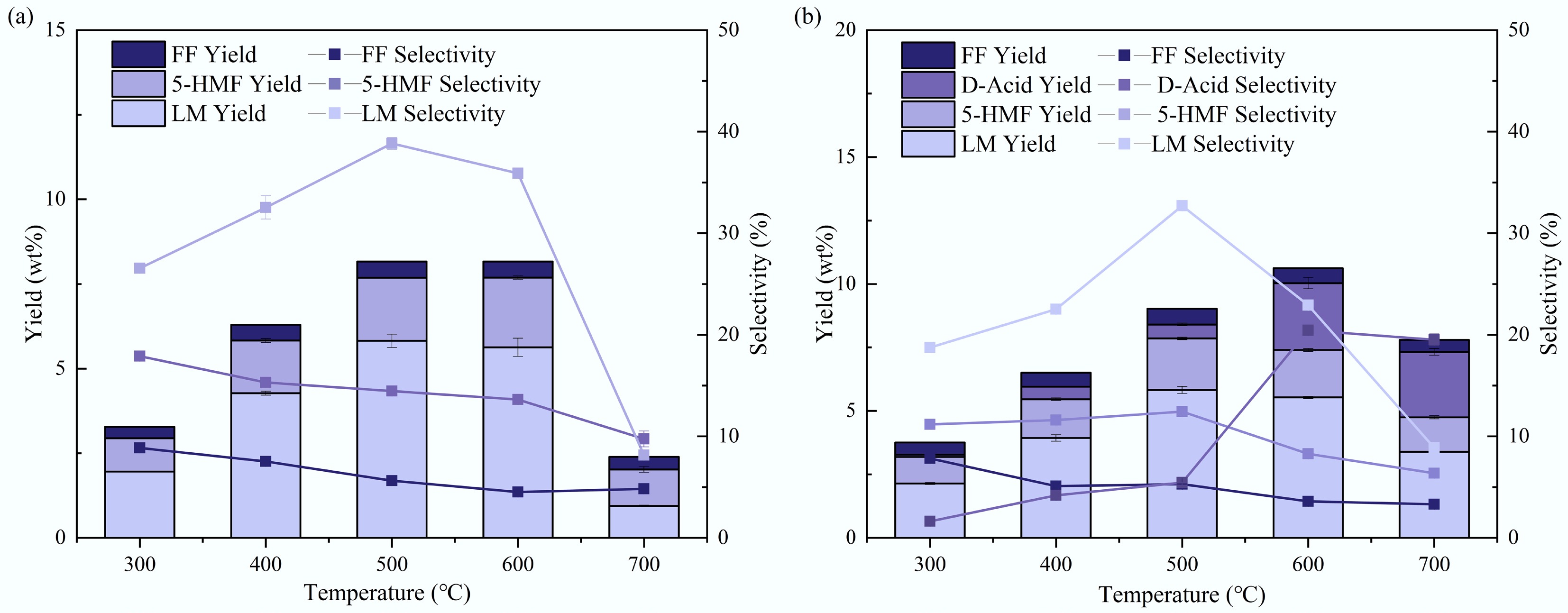

Bio-oil was detected by GC/MS, with the ion chromatograph shown in Supplementary Fig. S2. The main pyrolysis products for both tagua nuts and bodhi roots were mainly LM, 5-HMF, and FF, similar to the results observed by Py-GC/MS. Differently, the peak of dodecanoic acid became obvious in bodhi root pyrolysis with the increase of temperature. The quantified yields and selectivity of these major products are illustrated in Fig. 8. As depicted in Fig. 8a, for tagua nut pyrolysis, the yield of LM exhibited a gradual upward trend with increasing pyrolysis temperature, reaching its maximum value of 5.8 wt% (selectivity 38.8%) at 500 °C. In contrast, the yield of 5-HMF maintained a consistent increasing pattern within the temperature range of 300–600 °C, attaining a peak yield of 2.0 wt% (selectivity 13.6%) at 600 °C. FF yields remained relatively low across the entire temperature range, with the highest yield of 0.5 wt% (selectivity 5.6%) observed at 500 °C. For bodhi root pyrolysis (Fig. 8b), the maximum LM yield was also 5.8 wt% (selectivity 38.8%) at 500 °C, which was identical to that of tagua nut. The 5-HMF yield of bodhi root peaked at 2.0 wt% at 600 °C, consistent with the peak temperature for tagua nut; however, its selectivity (8.2%) was notably lower than that of tagua nut. Similar to tagua nut, the overall FF yield of bodhi root was minimal, with the maximum yield of 0.6 wt% (selectivity 3.6%) achieved at 500 °C. The yield of dodecanoic acid displayed a steady increase with temperature, achieving a maximum of 2.6 wt% (selectivity 20.4%) at 600 °C, which was unique to bodhi root pyrolysis products. Compared to the results of Py-GC/MS, the yield of dodecanoic acid in the fixed-bed pyrolysis was more prominent. This might be because its boiling point is relatively high at 299 °C, and a prolonged high-temperature reaction is more conducive to its collection and analysis. Notably, the product yield of fixed-bed pyrolysis is significantly lower than that of Py-GC/MS pyrolysis, which was attributed to the decomposition of volatiles in the fixed-bed reactor and the polymerization of volatiles during condensation[34].

Figure 8.

Yields and selectivities of main pyrolysis products of (a) tagua nut and (b) bodhi roots in the lab-scale pyrolysis.

Discussion on the pyrolysis mechanism of the mannan-rich feedstocks

-

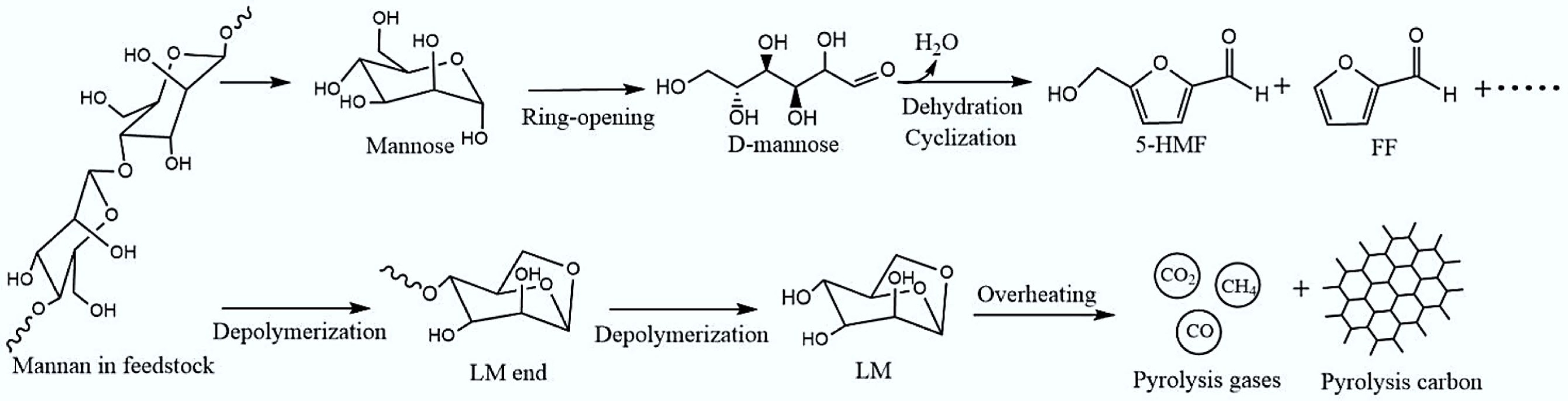

The structural characteristics of tagua nuts and bodhi roots directly dictate their pyrolysis pathways and product distributions, with high mannan content serving as the core structural determinant. The possible pyrolysis pathway of mannan in these two feedstocks is illustrated in Fig. 9. During the initial stage of pyrolysis, mannan underwent depolymerization via the cleavage of glycosidic bonds, generating oligosaccharides and monosaccharides. The transglycosylation reaction led to the formation of a 1,6-acetal ring, which was important for the formation of LM, similar to the formation of LG in cellulose pyrolysis[35]. As the temperature gradually increased to 350 °C, the absorption band of O–H groups (3,200–3,700 cm−1) decreased sharply. This spectral change indicated that mannan initiated dehydration. Meanwhile, the emergence of a stretching vibration peak for C=O bonds (1,704–1,749 cm−1) suggested that monosaccharides underwent isomerization and cyclization reactions, which produced 5-HMF and other furan derivatives.

Based on the results of the fixed-bed experiment, it could be observed that when the temperature further rose, LM (the main intermediate product) underwent additional dehydration and bond cleavage reactions. The breaking of C–C and C–O bonds in LM resulted in the generation of small-molecular-weight gases (e.g., CO2, CO, CH4). When the temperature reached 700 °C, the yield of these gases (calculated by mass fraction) exceeded that of water, bio-oil, and biochar, which was consistent with the extensive cleavage of LM and other intermediates at elevated temperatures (Fig. 7). As a result, both 5-HMF and LM yields exhibited a trend of first increasing and then decreasing with rising pyrolysis temperature, while the yield of LM (as a labile intermediate) decreased more significantly at high temperatures (> 500 °C, Fig. 8). However, this situation was not observed in the results of Py-GC/MS. This was because the reaction time in the fixed-bed experiment was longer, and the products were more prone to undergo secondary reactions, which led to an additional attenuation in the LM yield under higher temperature conditions.

In summary, the structure-reaction-product correlation established in this study provided a theoretical basis for the selective conversion of palm-based handicraft wastes. To target LM production, feedstocks with low ash content and high mannan content (e.g., tagua nuts) should be selected, and the pyrolysis temperature should be controlled at 500–600 °C to balance LM formation and avoid excessive decomposition of LM.

-

The typical palm-based handicraft wastes, tagua nut and bodhi root, were employed as feedstocks to investigate their chemical structures, pyrolysis behaviors, and product distributions. Firstly, the chemical compositions and structural characteristics of tagua nut and bodhi root were systematically characterized. Results indicated that both materials possessed low lignin and ash contents, with holocellulose contents of 92.8% and 86.8%, respectively. Notably, mannan was the dominant component in holocellulose, accounting for 87.5% and 88.0% of the total holocellulose content for the two materials, respectively. TG-FTIR analysis revealed that the maximum weight loss temperatures of tagua nut and bodhi root were 301 and 302 °C, respectively, with corresponding residual carbon contents of 24% and 21%. Fixed-bed pyrolysis experiments demonstrated that the liquid product yield first increased and then decreased with temperature, peaking at 600 °C for both materials. GC/MS analysis of the liquid products of fixed-bed pyrolysis identified LM, 5-HMF, and FF as major pyrolysis products. The highest LM yield in the liquid fraction reached 5.8 wt%, while 5-HMF exhibited a maximum yield of 2.0 wt%. Notably, dodecanoic acid emerged in the pyrolysis products of bodhi roots when the temperature exceeded 400 °C, a feature absent in tagua nut pyrolysis. Integrating these findings, the correlation between chemical composition and thermal decomposition behavior was carefully discussed. This work can provide fundamental insights into the thermochemical conversion potential of these mannan-rich biomass resources.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/een-0025-0020.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Bin Hu: data collection and analysis, conceptualization and the first draft of the manuscript, funding acquisition, study conception and design. Guan-zheng Zhou: data collection and analysis, study conception and design. Wan-yu Fu: data collection and analysis, study conception and design. Hao Fu: study conception and design. Jin-tian Liu: study conception and design. Guo-mao Yang: data collection and analysis, study conception and design. Ji Liu: funding acquisition, study conception and design. Kai Li: data collection and analysis, study conception and design. Qiang Lu: funding acquisition and resources, supervision and project administration, study conception and design. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript, reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 52276189, 52436009, 52376182), and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. 2024JG001).

-

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

-

Structural and pyrolytic chemistry of palm-based handicraft wastes were carefully explored.

Both tagua nut and bodhi root were characterized with high contents of mannan and low content of lignin and ash.

Levomannosan was the dominant pyrolysis product, accounting for over 90% of bio-oil.

Bodhi root uniquely produced dodecanoic acid due to its higher fat content.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- The supplementary files can be downloaded from here.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Hu B, Zhou GZ, Fu WY, Fu H, Liu JT, et al. 2026. Pyrolysis of the palm-based handicraft wastes: structure, reactions, and products. Energy & Environment Nexus 2: e003 doi: 10.48130/een-0025-0020

Pyrolysis of the palm-based handicraft wastes: structure, reactions, and products

- Received: 08 November 2025

- Revised: 09 December 2025

- Accepted: 17 December 2025

- Published online: 15 January 2026

Abstract: The mannan-rich palm handicraft processing wastes are potential feedstocks to produce high-value anhydrosugars through pyrolysis. However, the correlation between their structural characteristics and the pyrolysis chemistry remains unclear. Herein, two kinds of common palm feedstocks, tagua nut and bodhi root, were taken to explore the structure and pyrolysis characteristics using different characterization and experimental methods. Thermogravimetry-infrared spectroscopy (TG-FTIR) and pyrolysis-gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (Py-GC/MS) were employed to systematically investigate the pyrolysis characteristics and product distribution of tagua nuts and bodhi roots. Notably, the two raw materials exhibited high mannan contents of 87.59% and 88.01%, respectively, which exerted a fundamental influence on their pyrolysis behavior. The TG-FTIR results demonstrated that the maximum weight loss temperatures of the two materials were 301 and 302 °C, respectively. Among the anhydrosugars in the pyrolysis products, the proportion of levomannosan (LM) exceeded 90%. In Py-GC/MS tests, the maximum LM yield from tagua nut was 11.2 wt% (at 600 °C), while that from bodhi root was 10.9 wt% (at 500 °C). During the lab-scale pyrolysis, the highest yields of the organic liquid products were 31.5 wt% and 29.5 wt% for the two feedstocks at 600 °C. In the liquid pyrolysis products, a maximum LM yield of 5.8 wt% and a maximum 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (5-HMF) yield of 2.0 wt% were obtained, with trace furfural (FF, 0.50 wt% for tagua nut, 0.61 wt% for bodhi root). Finally, the pyrolysis mechanism of the two materials, especially the formation of LM, was discussed. The present work lays a foundation for the production of important anhydrosugars from the mannan-rich biomass wastes.

-

Key words:

- Pyrolysis /

- Tagua nut /

- Bodhi root /

- Py-GC/MS /

- TG-FTIR /

- In-situ DRIFT