-

Biochar technology, a key negative-emission route in the pursuit of carbon neutrality, involves the thermochemical conversion of biomass into a stable, carbon-rich material under oxygen-limited conditions[1−3]. Historically rooted in the creation of Amazonian Dark Earths, biochar's use has evolved from soil conditioning to functional materials design[4]. Modern research now emphasizes the engineered control of physical properties to tailor biochar for specific applications, ranging from environmental remediation to energy devices[5−8].

The physical properties of biochar mainly include pore structure, specific surface area, mechanical strength, electrical conductivity, thermal conductivity, and light absorption conversion. These properties determine the applicability and efficiency of biochar in various environments, as shown below: (1) Pore structure is one of the most core physical properties of biochar, encompassing pore size distribution, pore volume, and morphological characteristics. The specific surface area directly reflects the pore structure. In pollutant adsorption, micropores provide a huge specific surface area and are the primary sites for the adsorption of heavy metal ions and small-molecular organic pollutants; mesopores are conducive to the adsorption and diffusion of larger molecular pollutants (such as dyes and antibiotics). The pore size distribution directly determines the adsorption selectivity and capacity of biochar. In agricultural applications, a hierarchical pore structure can improve soil water retention, nutrient retention capacity, and microbial habitat. In the field of catalysis, mesopores and macropores serve as mass transfer channels to improve mass transfer efficiency, while micropores are conducive to the dispersion and fixation of active components. (2) Mechanical strength refers to the ability of biochar to resist breakage and wear, often characterized by hardness. This property plays a decisive role in the long-term retention and stability of biochar after application. (3) Electrical conductivity measures biochar's ability to conduct electrical current, which depends on the continuity and order of the sp2-hybridized carbon within its carbon skeleton. High electrical conductivity ensures rapid electron transport within the electrode material, reduces internal resistance, and is an important foundation for building high-performance supercapacitors, battery electrodes, and electrochemical sensors. (4) Thermal conductivity and light absorption conversion are two critical, interrelated factors when using biochar in photothermal applications. Excellent light-to-heat conversion ability enables biochar to efficiently transform light energy into thermal energy, while thermal conductivity governs the distribution and transfer rate of the generated heat. Together, they determine the actual effectiveness of biochar in solar-driven water evaporation, photothermal catalysis, and thermal management systems.

Despite extensive progress in characterizing these physical attributes, a fundamental challenge remains: biochar's structure is highly heterogeneous and evolves through complex, multiscale thermochemical pathways, making it difficult to establish predictive structure–property relationships. To address this gap, the concept of a 'physical genome' of biochar has been introduced. It interprets features such as the degree of graphitization, pore connectivity, and defect density as inheritable and combinable structural units similar to genetic elements. This physical genome captures how feedstock composition and thermochemical conditions regulate the expression of these structural units, and how their interactions collectively determine macroscopic properties such as adsorption capacity, mechanical robustness, electron/heat transport, and photothermal conversion.

To operationalize the physical-genome perspective, it is essential to understand how specific structural units manifest across biochar's hierarchical carbon architecture. By mapping these multiscale configurations to functional outcomes, the physical genome framework provides a coherent route toward a predictive and design-oriented understanding. Building on this foundation, this review systematically dissects these interconnected attributes, highlights their coupling mechanisms, and consolidates recent experimental and theoretical advances. It concludes with key research challenges and a forward-looking roadmap for next-generation functional biochar.

-

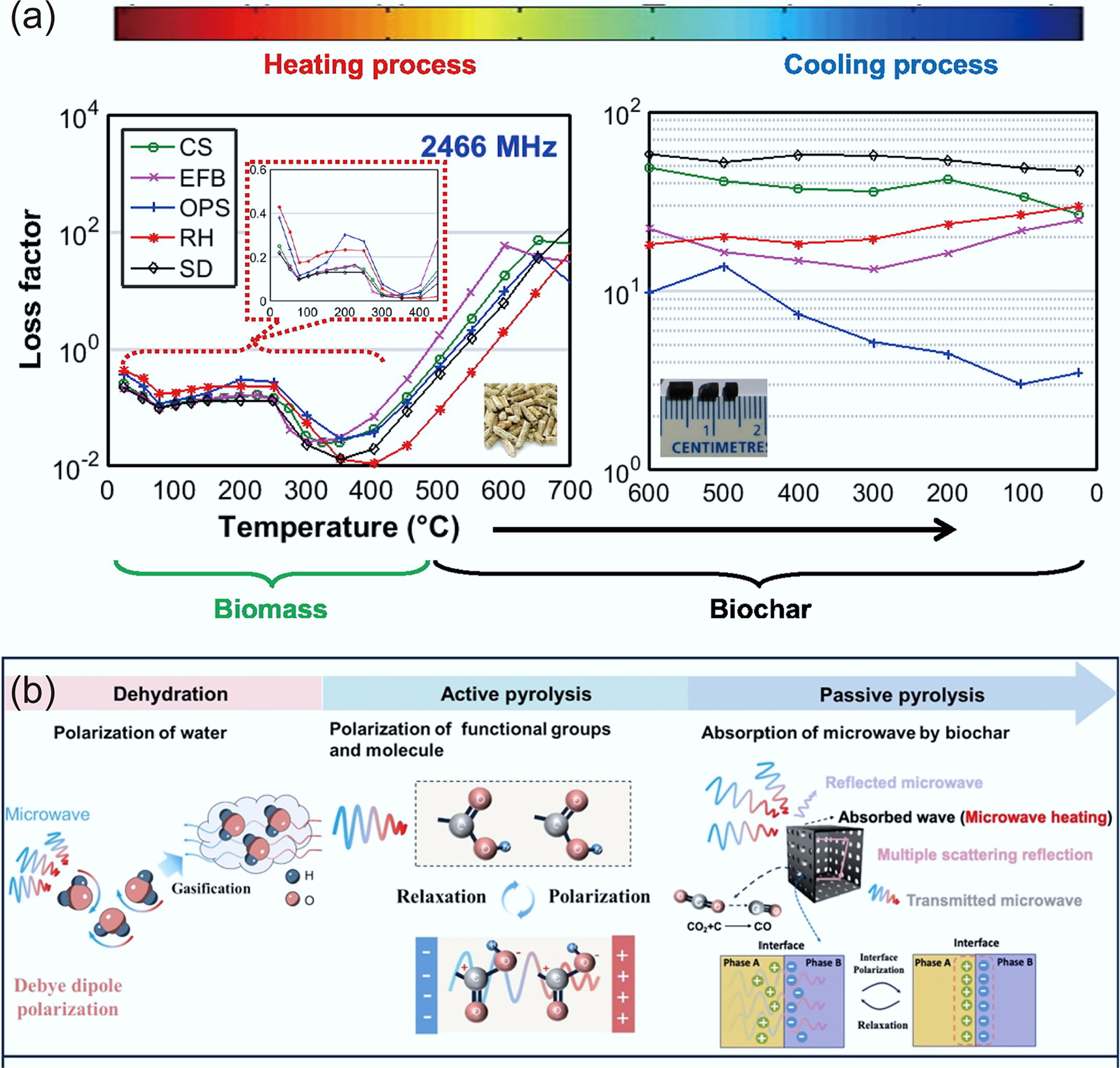

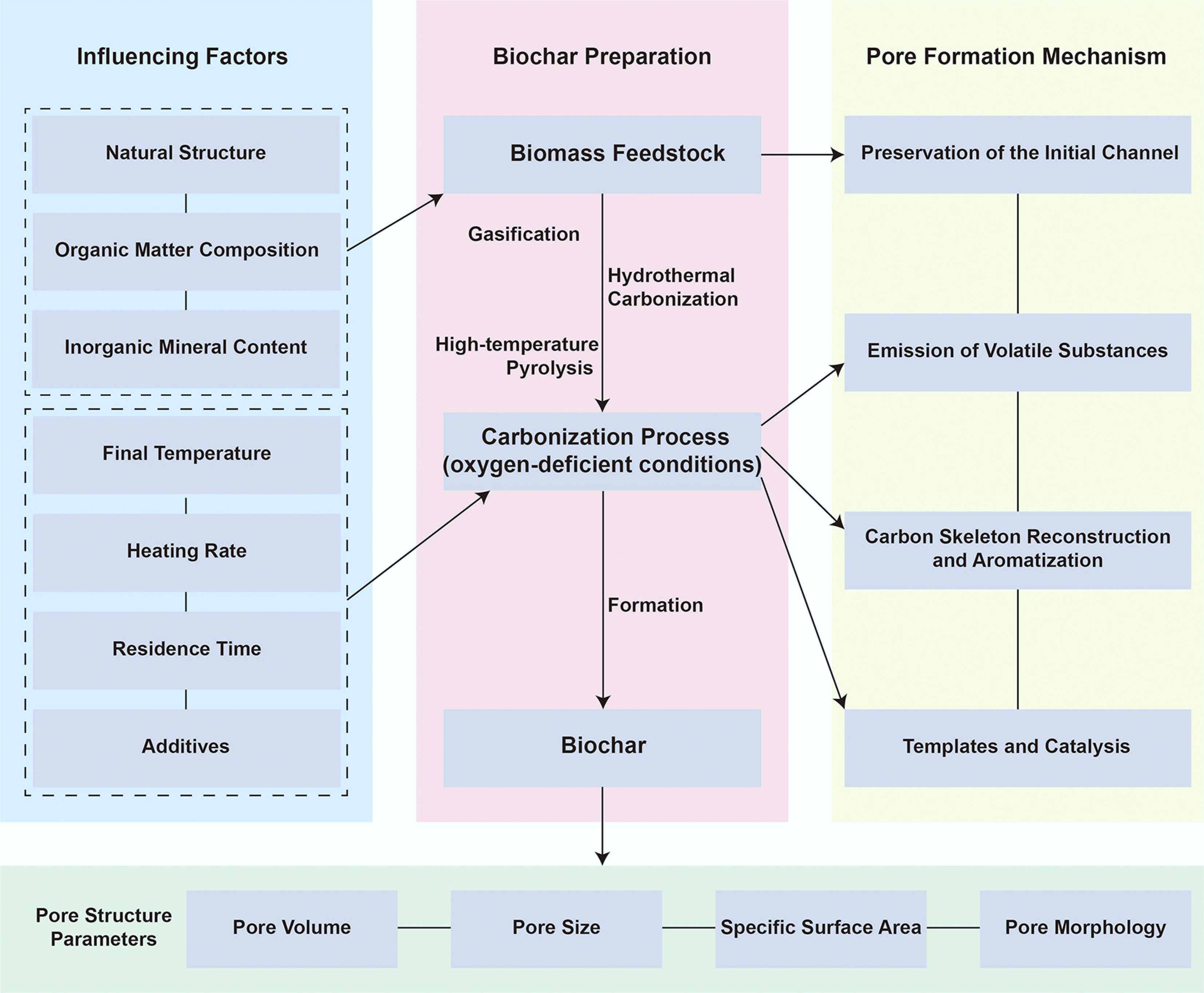

Biochar's pore system originates from the biological structure of its feedstock and evolves through multistage pyrolysis. Initial cellular pores form the structural backbone; volatile release opens micro- and mesopores; and carbon skeleton rearrangement at elevated temperatures (> 500 °C) consolidates graphitic domains. Feedstock composition and inorganic mineral content further influence pore evolution through catalytic and templating effects. Figure 1 shows the formation mechanism and influencing factors of biochar pore structure.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the formation mechanism and influencing factors of biochar pore structure.

Origins of porosity: from biomass anatomy to carbon frameworks

-

The formation of porosity in biochar begins with the initial pore structures derived directly from biomass anatomy. Lignocellulosic materials such as wood and straw possess intrinsic biological architectures, including vascular bundles, lumens, and intercellular layers. These structures serve as natural micro- and nano-channels that transport water and nutrients during plant growth. During the initial phase of pyrolysis, under relatively mild thermal conditions, these innate pore networks are largely preserved rather than destroyed. They act as a structural blueprint, forming the initial porous framework upon which further pore evolution is built. This direct structural inheritance underscores the critical role of biomass selection and anatomical features in determining the foundational porosity of the resulting biochar.

Evolution pathways: volatile release and graphitic reconstruction

-

Pore creation through volatile release represents the core mechanism for the in situ creation of new pores. Biomass components—cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin—undergo thermal decomposition at elevated temperatures, generating substantial volumes of volatile compounds (e.g., CO, CO2, CH4, and tars). The effusion of these volatiles from the solid matrix acts as a dynamic scouring force, forcibly evacuating and opening up previously inaccessible spaces. This process primarily generates a multitude of micropores (< 2 nm) and mesopores (2–50 nm), effectively perforating the carbon scaffold with countless nano-scale tunnels and channels. The rate and extent of this volatile release are critical determinants of the specific surface area and the final pore volume in the resulting biochar. A key insight emerging from recent studies is that hierarchical porosity (micro–meso–macro) is critical to multifunctionality: micropores provide high surface area for adsorption and charge storage; mesopores facilitate molecular transport; and macropores act as mechanical supports. Comparative analyses indicate that lignocellulosic feedstocks with high lignin content produce biochar with well-preserved channel networks and superior structural stability. Conversely, manure- or sludge-derived biochars tend to be more amorphous, with lower surface areas.

It is worth noting that the carbon skeleton shrinks to some extent as the aromatization process begins. Following a major volatile release, as temperatures exceed 500 °C, the carbon structure itself undergoes a fundamental transformation. The remaining carbon-rich solid begins a process of aromatization and gradual alignment into nascent graphite-like crystallites. During this condensation and graphitization, the carbon skeleton becomes more ordered and contracts, releasing non-carbon elements such as hydrogen[9]. This structural tightening and reordering enhance the material's stability. It also drives pore development by widening existing pores, creating fissures between growing crystallites, and refining pore walls to produce a more robust porous network.

Tuning the pore hierarchy

-

Biomass feedstock type is the primary factor affecting pore structure. Khater et al. measured the pyrolysis characteristics of various agricultural wastes (straw rice, sawdust, sugar cane, and tree leaves). Their results indicated that rice straw exhibited the highest porosity (63.7%) at a pyrolysis temperature of 400 °C[10]. He et al. cut balsa, pine, and bass wood into slices and carbonized them at 1,000 °C for 6 h using Ar as a protective gas. The BET test results showed that pine had the largest specific surface area, while basswood had the smallest (687.96 > 592.36 > 31.88 m2/g)[11]. Mašek et al. found that the specific surface area of softwood pellets exceeded that of oilseed rape straw at identical pyrolysis temperatures (26.4 > 7.3 m2/g, 550 °C), with the disparity becoming more pronounced as temperature increased (162.3 > 25.2 m2/g, 700 °C)[12]. Wang et al. investigated the pyrolysis behavior of corn stalk (CS), corn cob (CC), and spruce wood (SW) at 600 °C[13]. Unlike CC and CS biochar, SW biochar exhibited vertically aligned microchannels and highly elongated tracheid structures. Additionally, SW demonstrated the largest specific surface area and pore volume, while CC displayed the smallest. Yang et al. summarized the pore structure characteristics of animal manure-derived biochar and found that, in the absence of activating agents, the specific surface area predominantly fell within the range of 5–40 m2/g[14]. Tomczyk et al. also noted that biochar produced from animal manure and solid waste feedstocks exhibited lower surface area compared to that derived from crop residues and woody biomass[15]. This discrepancy was attributed to substantial differences in lignin and cellulose content, as well as biomass moisture levels.

Secondly, pyrolysis temperature is another important influencing factor. Regardless of the feedstock, high pyrolysis temperatures increase the specific surface area and pore volume of biochar. This effect is largely attributed to the intensified decomposition of organic compounds[16,17]. For example, Song et al. investigated the effect of pyrolysis temperature (300–700 °C) on biochar produced from pineapple leaf (PAL), banana stem (BAS), sugarcane bagasse (SCB), and horticultural substrate (HCS). Raising the pyrolysis temperature from 300 to 500 °C markedly increased the surface areas of all four biochars. For PALB, BASB, SCBB, and HCSB, the values rose from 1.80, 3.26, 2.38, and 2.44 m2/g to 3.30, 56.92, 2.77, and 24.96 m2/g, respectively. A further increase in temperature to 700 °C resulted in surface area increases of 65, six, 70, and five times, respectively, compared to those obtained at 500 °C[18]. Handiso et al. found that increasing the pyrolysis temperature from 300 °C to 500 °C greatly boosted the specific surface area (1.20 → 393 m2/g) and total pore volume (0.0151 → 0.1972 cm3/g) of pine-based biochar. At the same time, the average pore diameter decreased from macropores (~50 nm) to mesopores (~2 nm)[19]. Zhang et al. found that raising the activation temperature from 700 to 1,000 °C nearly doubled the specific surface area and total pore volume of bamboo-based biochar. At the same time, the average pore width decreased from 3.044 to 2.282 nm[20]. Quantitative synthesis across studies reveals that pyrolysis temperature consistently enhances surface area and pore volume up to an optimal range (500–700 °C), beyond which pore coalescence or collapse occurs. However, some exceptions were observed where the specific surface area and pore volume initially increased and then decreased with rising pyrolysis temperature. For instance, Liao et al. reported that during biochar production from bamboo and rice husk between 300 and 600 °C, the maximum specific surface area and pore volume occurred at 500 °C. They attributed this phenomenon to the collapse of porous structures caused by secondary pyrolysis of the biomass[21].

The third major influencing factor is activation. Biomass contains certain inorganic minerals (such as K, Ca, and Si, which become ash upon combustion). These minerals occupy a certain space within the carbon matrix. During subsequent acid washing or combustion, their removal leaves behind pores of comparable size and morphology. Furthermore, alkali and alkaline earth metals catalyze carbon gasification reactions (C + H2O → CO + H2; C + CO2 → 2CO), selectively oxidizing carbon atoms. This process expands existing pores or opens closed pores into through-pores, significantly increasing the specific surface area. The supplemental addition of activators (water vapor, CO2, NH4, KOH, H2SO4, CuCl2, etc.) and templates (MgO, triblock copolymer, etc.) can amplify these templating and catalytic effects, enabling precise pore structure regulation[22].

The resulting structure–property control forms the foundation for tuning mechanical, electrical, and thermal functions. Table 1 summarizes the pore volume, pore diameter, and specific surface area values of various common biochars.

Table 1. Pore structure characteristics of various biochars

Feedstock

typeSynthesis strategy Specific conditions Pore volume (cm3/g) Pore size Specific surface area (m2/g) Ref. Poplar wood Medium-temperature pyrolysis → High-temperature annealing → Air oxidation activation N2, 500 °C, 1 h, 1,000 °C, 2 h. Air, 450 °C, 1 h / Channel:

10–80 μm663 [23] Inert atmosphere high-temperature pyrolysis → Metal-induced activation FeCl3, CoCl2

Ar, 800 °C, 1 h/ Average pore size: 0.5 nm 334 [24] Low-temperature pre-carbonization → High-temperature pyrolysis under inert atmosphere → CO2 physical activation → Salt-assisted structure regulation 240 °C, 6 h, Ar, 1,000 °C, 6 h. CO2, 800 °C, 10 h. Salt impregnation, 150 °C, 2 h / 8–13 μm,

30–50 μm810 [25] Balsa wood Inert atmosphere high-temperature pyrolysis → Alkali impregnation and chemical activation Ar, 1,000 °C, 6 h, Ultrasonic.

Alkali impregnation, N2, 700 °C,

2 h/ Average pore size: 40 μm 809 [11] Hydrothermal precursor construction → Oxidative modification → High-temperature pyrolysis under inert atmosphere Impregnation dopamine, Hydrothermal,

Co(NO3)2, 60 °C, 2 h, H2O2, 2h. N2, 800 °C, 2 h0.163 Average pore size: 2.43 nm 110 [26] Inert atmosphere pyrolysis → Metal-induced activation FeCl3 impregnation, N2, 600 °C,

2 h0.118 Average pore size: 3.88 nm 275 [27] Pine wood Inert atmosphere high-temperature pyrolysis → Doping/metal-induced activation NH4Cl impregnation, Ar, 1,000 °C, 3 h. CuCl2 impregnation, Ar, 1,000 °C, 3h 0.250 Average pore size: 2.55 nm 582 [28] Inert atmosphere high-temperature pyrolysis → Metal-induced structure regulation 800 °C, 0.5 h, N2. Ni(NO3)2·6H2O, 800 °C, 1 h, N2 0.804 Average pore size: 3.96 nm 813 [29] Pyrolysis and annealing in an inert atmosphere 500 °C, 3 h and 450 °C, 4 h, N2 0.197 Average pore size: 2.01 nm 393 [19] Bamboo Hydrothermal carbonization → Chemical activation → Medium-temperature pyrolysis activation Hydrothermal, 200 °C, 6 h. H3PO4 impregnation, 600 °C, 2 h 1.09 Average pore size: 2.42 nm 1,798 [30] Low-temperature pre-carbonization in an inert atmosphere → High-temperature primary carbonization in an inert atmosphere N2, 200 °C, 1 h, 700 °C, 3 h 1.51 Average pore size: 2.28 nm 2,715 [20] Introduction of nitrogen source and gaseous foaming agent → Alkali impregnation and chemical activation → Microwave rapid pyrolysis/activation Urea, urea nitrate, KOH, microwave, 460 W, 30 min 0.66 1–5 nm 1,195 [31] Rice husk Medium and high temperature carbonization 395–618 °C, 4 h 0.255 / / [32] Corn cob 0.243 / / Bamboo Intermediate-temperature pyrolysis under an inert atmosphere 500 °C, 1 h, N2 0.099 6.24 nm 71 [21] Rice husk 0.039 3.42 nm 29 Corn cob 0.023 2.39 nm 10 Sewage sludge Medium temperature carbonization 400 °C, 1 h / 10.6 nm 1 [33] Pine needles / 2.16 nm 430 Pineapple leaves Medium and high temperature carbonization 300–700 °C, 2 h 0.01–0.1 1–9 nm 1–215 [18] Banana stems 0.01–0.18 2–8 nm 3–335 Sugarcane bagasse 0.01–0.1 2–6.5 nm 2–195 Horticultural substrate 0.01–0.09 3–16 nm 2–120 Chicken manure Calcination at 550–950 °C for 4 h / 15.4–15.7 nm 11 [34] Swine manure Intermediate-temperature pyrolysis under an inert atmosphere Pyrolysis at 500–650 °C for 2 h

in N20.032–0.038 15.4–26.0 nm 6–8 [35] Pyrolysis at 500 °C for 4 h in Ar 0.021 6.76 nm 13 [36] Cow manure Intermediate-temperature pyrolysis under an inert atmosphere → Metal-induced structure regulation Impregnation with CuSO4, Pyrolysis at 500 °C for 4 h in Ar 0.031 4.85 nm 26 -

Mechanical robustness determines the long-term stability of biochar in both environmental and engineered systems. It is not a singular attribute but a complex outcome of feedstock selection, pyrolysis conditions, and subsequent environmental interactions. Feedstock chemistry (notably lignin content) and pyrolysis temperature govern the formation of cross-linked aromatic networks, which impart rigidity. At moderate pyrolysis temperatures (500–700 °C), biochar attains an optimal balance between strength and toughness, whereas excessive graphitization (> 900 °C) induces brittleness. Furthermore, the mechanical stability of the resulting carbon framework is subject to the multifaceted interplay of post-processing techniques and long-term environmental exposure.

Feedstock chemistry and the formation of carbon networks

-

The inherent properties of the feedstock are the primary determinants of biochar's mechanical performance. Their influence is profound and persists throughout the entire conversion process. The chemical composition of the feedstock, particularly the content and nature of lignin and ash, plays a predominant role in this regard. Feedstocks rich in lignin, including wood and nut shells, promote the formation of a rigid, cross-linked aromatic carbon framework during pyrolysis. This structure imparts high compressive strength and abrasion resistance to the resulting biochar[37,38]. Conversely, feedstocks with high ash content—such as livestock manure or sewage sludge—tend to produce biochar with weaker and more friable mechanical properties. The substantial inorganic mineral content disrupts the formation of a continuous carbon matrix, leading to a porous and fragile structure[39,40]. Furthermore, the physical structure of the feedstock is equally crucial. Dense lignocellulosic feedstocks with inherent fibrous structures, such as hardwoods or bamboo, retain a partially preserved anisotropic supporting framework after carbonization[41,42]. This natural 'fiber-reinforcement' effect typically grants the resulting biochar greater toughness and structural integrity. Consequently, selecting feedstocks with high lignin content, low ash content, and a dense physical structure is a primary prerequisite for producing biochar with high mechanical strength. This provides a fundamental basis for the targeted design and optimization of biochar properties to meet the specific mechanical requirements of various application scenarios.

Pyrolysis-driven strength evolution

-

Pyrolysis temperature primarily governs the mechanical properties of the final material by altering the structural ordering of the carbon skeleton, pore evolution, and ash behavior[43,44]. At relatively low temperatures (< 400 °C), biomass undergoes initial devolatilization and carbonization, but the organic structure of the precursor is not fully reconfigured[45]. The resulting biochar retains substantial amorphous carbon and incompletely pyrolyzed organic components, typically exhibiting weak mechanical strength, soft texture, and high friability[46].

When the temperature reaches the medium range (500–700 °C), the mechanical performance changes markedly. Aromaticity intensifies, carbon microcrystals grow and align, and graphitic domains form a stronger, more stable three-dimensional cross-linked network[47]. This significantly enhances mechanical strength, hardness, and compressive resistance. However, vigorous volatile release and pore coalescence may also introduce structural defects, increasing brittleness[48].

At temperatures above 700 °C, the carbon skeleton evolves into a highly graphitized structure. This graphite-like framework exhibits markedly higher hardness and abrasion resistance[49]. Nevertheless, excessive shrinkage and pore coarsening can promote macro-crack propagation, thereby reducing overall toughness and exacerbating brittleness.

Additionally, temperature can indirectly influence mechanical properties by affecting ash fusion. In feedstocks rich in alkali and alkaline earth metals, the molten ash formed at high temperatures acts as a natural binder that enhances particle bonding. However, ash volatilization at extreme temperatures may leave structural weaknesses.

Therefore, the effect of pyrolysis temperature on the mechanical properties of biochar presents a complex non-monotonic change. There is an optimal temperature window that varies depending on the raw material. Within this temperature window, biochar achieves its best balance of strength, hardness, and toughness. This balance is critical for applications such as soil conditioning, carbon sequestration, and composite reinforcement.

Nanoindentation insights: hardness and modulus

-

Nanoindentation technology has provided key insights into the intrinsic mechanical properties of biochar solid skeletons at the nanoscale. Nanoindentation studies reveal a wide hardness range (0.3–4.5 GPa) depending on feedstock and temperature. Zickler et al. studied the evolution of mechanical properties in spruce wood pyrolyzed up to 2,400 °C using nanoindentation. Hardness increased continuously, reaching 4.5 GPa at 700 °C. In contrast, the indentation modulus varied non-linearly, with a minimum of 5 GPa at 400 °C and a maximum of 40 GPa at 1,000 °C[50]. Das et al. systematically investigated the relationship between the hardness and elastic modulus of seven types of waste-derived biochars (including pine sawdust, sewage sludge, and softwood) and their preparation conditions. The results indicated that pine sawdust-derived biochar exhibited the highest hardness and elastic modulus (900 °C × 60 min), reaching 4.29 and 25.01 GPa, respectively. Both hardness and elastic modulus rose with increasing pyrolysis temperature and longer processing duration. Among these factors, temperature exerted the greater influence[38]. Furthermore, they compared the mechanical properties of the biochar with those of waste pinewood and pure polypropylene (PP). The results indicated that the biochar exhibited the highest hardness (0.43 GPa), followed by pinewood (0.3 GPa) and PP (0.1 GPa). Conversely, the modulus values for these materials were 4.9, 5.6, and 1.5 GPa, respectively[51]. The type of pyrolysis reactor also has an important influence on the mechanical properties of biochar. Das et al. found that biochar produced in the hydrothermal reactor had the lowest nanoindentation properties. In contrast, tube-reactor biochar generated at 300 °C showed the highest hardness (290 MPa) and modulus (~4 GPa)[52]. Table 2 lists the hardness and modulus of different types of biochar determined by nanoindentation.

Table 2. Hardness and modulus of different types of biochar measured by nanoindentation

Feedstock type Synthesis strategy Specific conditions Hardness (GPa) Modulus (GPa) Ref. Pinewood Medium and low temperature carbonization 450 °C, 10 min 0.43 4.9 [51] Birch wood 300 °C, 1 h 0.27 3.9 [52] Chicken litter 450 °C, 20 min ~0.75 ~5 [38] Spruce wood Medium and high temperature carbonization 700–2,000 °C, 2h 4–5 30–40 [50] Sewage sludge 680 °C, 10 min ~2.5 ~10 [38] 90% softwood and 10% hardwood − − 0.28 5.1 [53] Fruit pit 0.22 3.4 Pine bark High temperature carbonization 800 °C, 1 h ~0.47 ~4.5 [54] Gluten 0.5 7.8 Pine sawdust 900 °C, 1 h 4.29 25 [38] Environmental and processing effects on mechanical stability

-

The mechanical stability of biochar is not solely dependent on its initial synthesis but is dynamically influenced by its external chemical environment and post-processing history. These external factors are dualistic, potentially disrupting the carbon framework or enhancing its functionality under specific conditions.

The chemical environment can directly alter the micromechanical properties of biochar through physical and chemical interactions. For example, Xu et al. found that a highly alkaline cement-simulated solution significantly decreased the Young's modulus and hardness of lignocellulosic biochar. This degradation was likely caused by chemical corrosion and subsequent pore-wall collapse. Conversely, exposure to a simulated seawater environment resulted in approximately 40% improvement in these mechanical properties compared to the original biochar. This enhancement is thought to be caused by the deposition of dissolved inorganic salts within the nanopores of the biochar, which effectively reinforces the pore walls and increases the structural density[55].

In addition to chemical exposure, physical post-processing is another important external factor. Crushing, grinding, or granulation can introduce microcracks. These microcracks act as stress concentration points and reduce the structural integrity of individual particles. Furthermore, during environmental deployment, biochar is subjected to cyclic stresses, including wet–dry cycles and freeze–thaw cycles. Water adsorbed in nanopores produces substantial capillary pressure during drying. When frozen, its expansion promotes microcrack propagation, leading to gradual mechanical fatigue.

Importantly, mechanical resilience correlates strongly with the degree of graphitization and microstructural continuity—properties that also influence conductivity. This shared dependence underscores the mechanical–electronic synergy within carbonized frameworks, suggesting design pathways for mechanically stable conductive composites.

-

The thermal properties of biochar are among its core attributes as a functional material. These properties determine its effectiveness in thermal energy storage and management and also strongly influence the efficiency of associated thermochemical conversion processes.

Phonon pathways and the role of structural disorder

-

Biochar's thermal behavior is governed by phonon transport through disordered carbon lattices[56,57]. The size, degree of order, and orientation of graphitic microcrystals are key to phonon transport efficiency. Larger, more ordered, and better-aligned crystals allow longer phonon mean free paths and thus higher thermal conductivity. However, the intrinsic structural characteristics of biochar are precisely the 'natural enemies' of phonons. Disordered pores, grain boundaries, heteroatoms, and other defects are widespread in biochar. Together, they create dense phonon-scattering centers that hinder the development of effective heat-conduction pathways. This is the fundamental reason why the intrinsic thermal conductivity of most pristine biochar is relatively low (typically below 1 W/m·K). At high temperatures, gas convection within pores and thermal radiation may also contribute to heat transfer. However, their effects are generally minor compared with conduction through the solid carbon matrix. It is noteworthy that this structure endows biochar with a dual nature in terms of thermal properties. The highly developed porous structure, while inhibiting conductive heat transfer, renders it an excellent thermal insulation material.

Processing parameters governing heat conduction

-

The thermal properties of biochar are not inherent but are shaped by precursor chemistry and processing conditions, making them highly tunable. Among the various influencing factors, pyrolysis temperature plays the most critical role. Generally, as the pyrolysis temperature increases from low ranges (e.g., 300–400 °C) to high ranges (> 700 °C), the thermal conductivity of biochar exhibits an improvement by orders of magnitude. This enhancement results from the graphitization of amorphous carbon at elevated temperatures. Aromatic domains condense and grow, defects are healed, and larger, more ordered graphitic microcrystals emerge, creating more efficient phonon-transport pathways. Zhang et al. reported that the thermal conductivity of pine wood biochar increased significantly with increasing pyrolysis temperature from 600 to 1,000 °C[58]. With increasing pyrolysis temperature, the enhanced graphitic order raised the thermal conductivity of wood-derived biochar from 0.1 to 0.4 W/m·K. Lv et al. also synthesized biochar from Phoenix leaves under varying pyrolysis temperatures, reporting that higher pyrolysis temperatures resulted in enhanced thermal conductivity of the material[59]. Liu et al. found that the thermal conductivity of a polyethylene glycol/corn stalk biochar composite phase change material was directly proportional to the pyrolysis temperature of the biochar component[60].

Beyond pyrolysis temperature, the chemical composition of the precursor feedstock is equally crucial. Lignin-rich feedstocks, such as pine, contain more aromatic structural units and thus form ordered carbon skeletons more easily during pyrolysis. As a result, they generally yield biochar with higher thermal conductivity than cellulose-dominated feedstocks like rice straw. Furthermore, the innate microstructure of the raw material (such as the anisotropic channels in wood) is also preserved in the derived biochar, leading to anisotropic heat conduction. For example, the longitudinal and transverse thermal conductivities of bamboo-derived biochar were 0.345 and 0.676 W/m·K, respectively[61]. A significant difference was observed in the maximum heat transfer temperatures of hemp-stem-derived biochar, with the radial direction reaching 41 °C, in contrast to 32 °C for the transverse direction[62]. In addition to chemical and structural parameters, macroscopic physical properties like bulk density show a significant correlation with thermal conductivity. The study conducted by Usowicz et al. demonstrated an inverse relationship between the thermal conductivity and bulk density of individual biochar types[63].

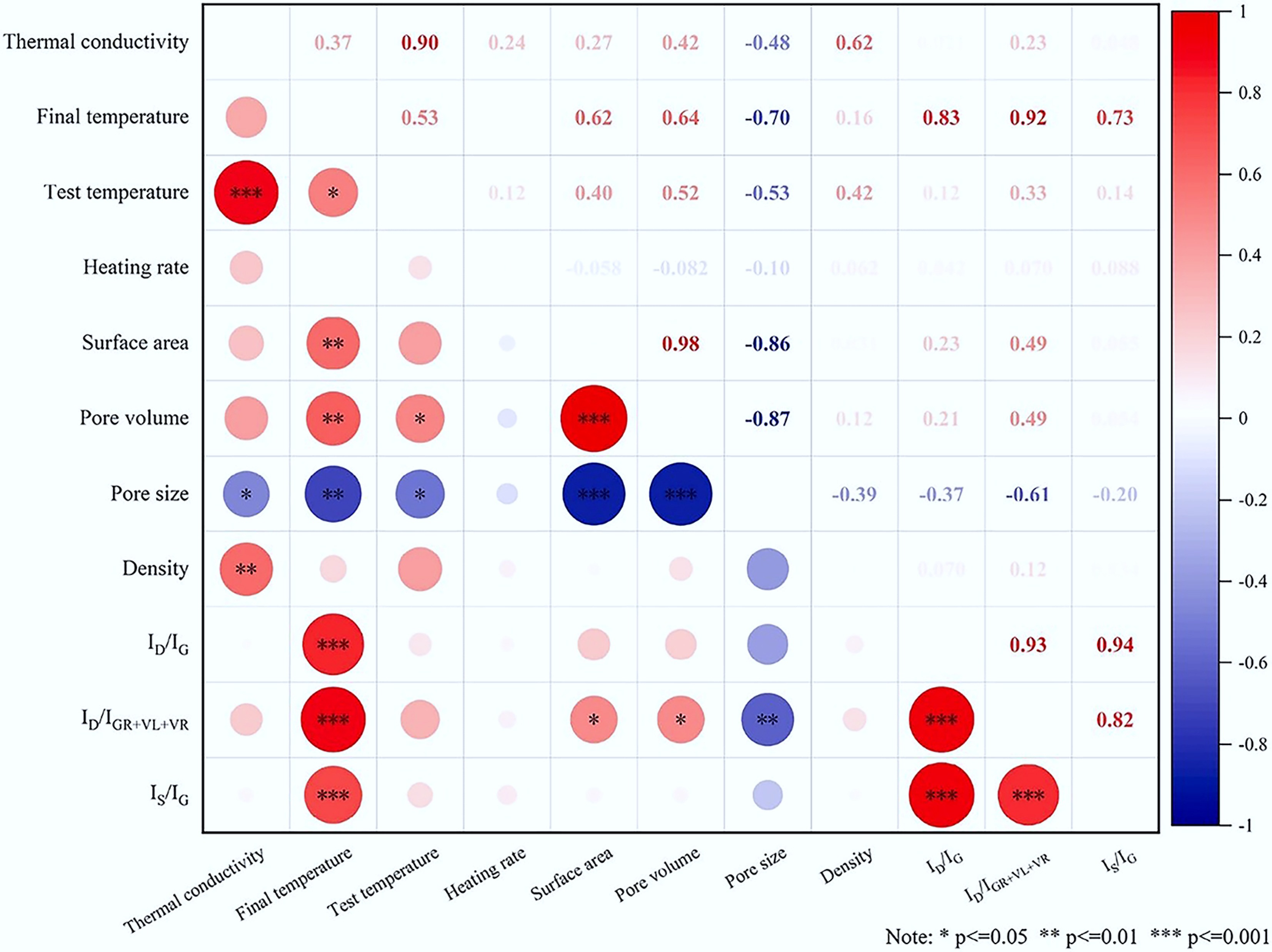

Furthermore, post-treatment processes offer additional avenues for tuning. For instance, although chemical activation (e.g., using KOH or H3PO4) can significantly increase specific surface area, the etching of the carbon skeleton during this process may introduce new defects, thereby compromising thermal conductivity. Conversely, catalytic graphitization or the addition of highly conductive nanomaterials can create hybrid thermal conduction networks. These strategies offer effective routes to significantly improving the thermal performance of biochar. Zhang et al. studied the effects of copper-based preservatives on the thermal conductivity of pine-based biochar. Biochar treated with copper-based preservatives showed a 70%–80% increase in thermal conductivity compared to untreated biochar[58]. Huang et al. analyzed the correlations of thermal conductivity, as illustrated in Fig. 2. The results identified that test temperature, density, and pore size were identified as the most influential factors, with their correlation strength decreasing in the order of: temperature > density > pore size[64].

Figure 2.

Correlation analysis of thermal conductivity[64].

In summary, the interplay between porosity and crystallinity offers tunability: while high porosity promotes insulation, graphitization enhances conductivity. Post-treatments, such as catalytic graphitization or metal nanoparticle doping, further optimize heat conduction. Representative thermal conductivity values for different biochar are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Thermal conductivity of different types of biochar

Feedstock type Synthesis strategy Specific conditions Thermal conductivity (W/m∙K) Ref. Lemon peel Medium and low temperature carbonization 180 °C, 1 h 0.84 [65] Wood offcuts 350–400 °C 0.079–0.132 [63] Phoenix leaf 450–600 °C, 2 h 0.056–0.06 [59] Garlic stem 700 °C, 2 h 0.141 [66] Pine wood High temperature carbonization 1,000 °C, 1 h 0.222 [58] Copper-based preservatives, 1,000 °C, 1 h 0.395 Bamboo 1,000 °C, 6 h 0.3–0.7 [61] Peanut shell 900 °C, 2 h combined with stearic acid (SA) 0.53 [67] Poplar wood 0.38 Corn straw 0.32 Thermal stability: aromatic networks and carbonization degree

-

Thermal stability is essential for carbon sequestration. It increases with higher aromaticity and lower oxygen content, which result from elevated pyrolysis temperatures and lignin-rich feedstocks[68]. High pyrolysis temperatures (typically above 400 °C) decompose unstable biomass components such as hemicellulose and cellulose and promote aromatic condensation and the development of graphite-like microcrystalline domains, which markedly improve biochar stability[69]. Lignin-rich feedstocks, such as pine, possess inherently three-dimensional aromatic polymer structures. As a result, they more easily develop highly cross-linked and stable carbon skeletons during pyrolysis. Compared to biochar made from cellulose-based feedstocks (such as straw), lignin-derived biochar generally exhibits superior thermal stability[70]. Furthermore, modification techniques such as physical or chemical activation and oxidation with hydrogen peroxide have also been found to affect biochar stability by altering its pore structure and surface functional groups[71,72].

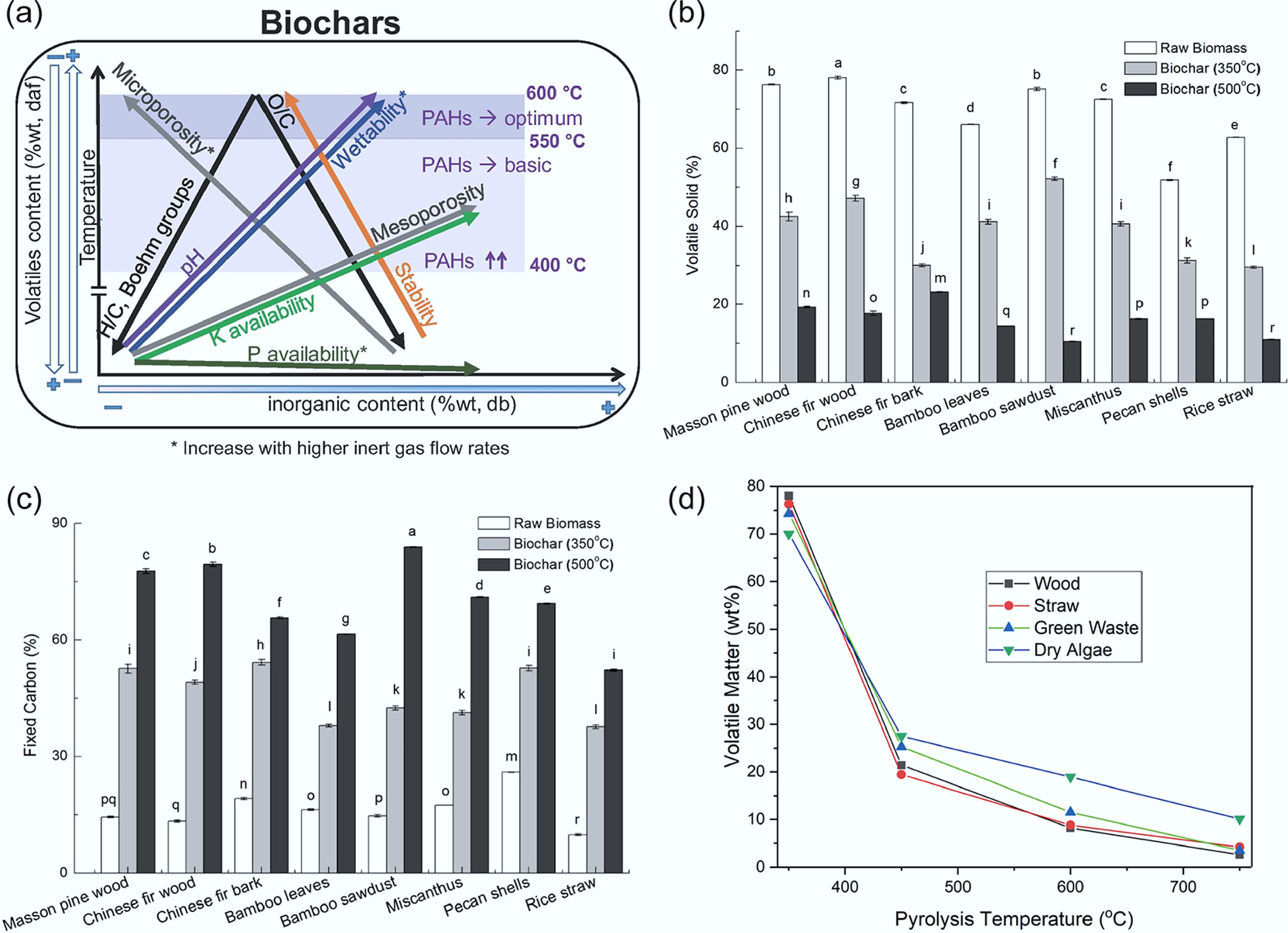

Alba and colleagues produced biochar from pine wood chips (PW) and corn digestate (CD) at pyrolysis temperatures of 400 and 600 °C (Fig. 3a). The results demonstrated that the PW-derived biochar exhibited significantly superior thermal stability compared to the CD-derived biochar. Furthermore, increasing the pyrolysis temperature from 400 to 600 °C enhanced both the carbon content and thermal stability of the resulting biochar[73]. Yang et al. systematically evaluated the thermal stability of eight types of biochar produced at 350 and 500 °C. The study revealed that an increase in pyrolysis temperature from 350 to 500 °C resulted in a notable rise in the release of volatile solids (Fig. 3b). This enhanced volatilization directly led to a significant enrichment of fixed carbon content in the biochar (Fig. 3c)[74]. Ronsse et al. also reached a similar conclusion. The results showed that the volatile matter in different types of biochar decreased with increasing temperature, as shown in Fig. 3d[75].

-

In recent years, the research frontier of biochar has significantly expanded beyond its conventional role in environmental adsorption to encompass its functional electrical properties. As a porous carbon material derived from the resource utilization of biomass waste, its unique electrical conductivity and dielectric behavior are garnering extensive attention within the fields of energy, electronics, and environmental science. This section reviews recent progress on the conductive mechanisms and dielectric properties of biochar. It also examines its transition from an environmental remediation material to a high-performance electronic medium and electrode. The aim is to provide a theoretical foundation and strategic guidance for developing the next generation of green, low-cost biochar-based electronic devices.

Graphitization and the formation of conductive networks

-

The electrical conduction mechanism in biochar primarily stems from the conjugated conductive network formed by aromatic carbon sheets during pyrolysis. With increasing pyrolysis temperature, hydrogen, and oxygen are removed as volatile compounds. This raises the proportion of sp2-hybridized carbon and drives the formation of graphite-like microcrystals[76,77]. These microcrystals establish efficient electron transport pathways through π–π stacking interactions, whose degree of perfection and structural ordering directly determine the intrinsic electrical conductivity[78].

The formation and performance of this conductive network are cooperatively regulated by several key factors. Primarily, pyrolysis conditions serve as the decisive element. Specifically, treatments above 700 °C significantly promote graphitization, while the heating rate and residence time influence the degree of structural ordering in the carbon framework[77,79]. Secondly, the chemical composition of the feedstock is crucial. Lignin-rich biomass, such as wood, more readily forms highly conjugated conductive structures due to its inherent aromaticity[80]. Furthermore, the introduction of heteroatoms, such as nitrogen or sulfur, can modulate the semiconductor properties by altering the local electron density. However, excessive doping may disrupt the continuity of the carbon network. In addition, the pore structure requires a balanced design. A moderate specific surface area with interconnected hierarchical pores ensures efficient electron conduction while also facilitating electrolyte ion transport. Finally, surface chemistry also plays a role. Residual oxygen-containing functional groups like carboxyl groups can act as scattering sites that impede charge carrier mobility. In contrast, specific groups like carbonyls may contribute additional pseudocapacitance through reversible redox reactions[81]. Therefore, precise regulation of these parameters enables the tailored design and optimization of biochar's electrical properties for specific application requirements.

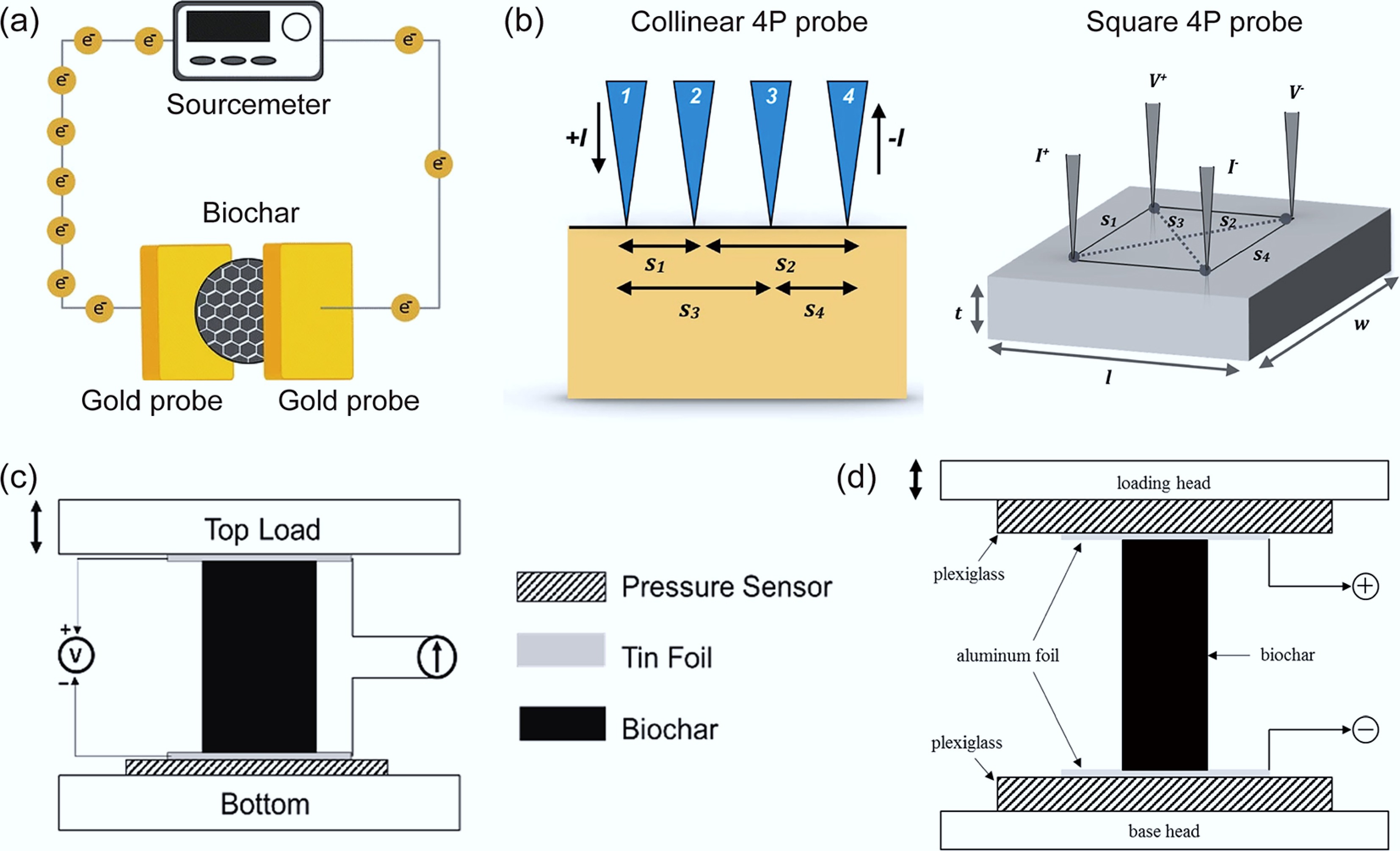

The initial measurement of biochar electrical conductivity was performed using the two-probe method, as illustrated in Fig. 4a[81]. In this configuration, the sample is positioned between two probes, and a known current is applied while the resulting voltage drop across the sample is measured by a potentiometer. The electrical conductivity is then calculated based on the resistivity of the biochar. A major limitation of the two-probe method lies in the difficulty of accurately estimating the contact resistance between the probes and the material. To address this constraint, the four-probe method was developed (Fig. 4b)[82]. However, this technique requires a thickness correction factor, which introduces systematic errors when the sample dimensions deviate from the thin-film ideal. To overcome the limitations inherent in both conventional methods, researchers have developed a modified two-probe approach, as schematically represented in Fig. 4c. The modified method measures bulk conductivity using a sandwich approach using two flexible conductive electrodes under constant pressure contact. Bulk conductivity is calculated from the applied current divided by the total geometric contact area with tin foil, combined with the measured potential drop along the sample length[76]. The specialized setup shown in Fig. 4d enables controlled compression of biochar samples and is designed to systematically investigate how electrical conductivity depends on compression conditions[78].

Dielectric response and frequency-dependent polarization

-

Dielectric behavior complements conductivity, enabling energy storage and electromagnetic applications. The dielectric properties of biochar can be characterized by its complex relative permittivity (Eq. [1]):

$ {\varepsilon }^{\mathrm{*}}={\varepsilon }{'}-{i\varepsilon }{''} $ (1) where, ε' represents the relative dielectric constant, indicating the material's ability to store electrical energy, and ε" signifies the relative dielectric loss factor, characterizing the dissipation of electrical energy into heat. These dielectric parameters exhibit a strong frequency dependence. In the low-frequency regime (e.g., below 1 GHz), interfacial polarization (often referred to as the Maxwell-Wagner-Sillars effect) is typically dominant. This mechanism arises from charge accumulation at interfaces between regions of different electrical conductivity within the biochar, such as aromatic carbon clusters, heteroatoms, and residual ash, leading to significant polarization[83]. As the frequency rises, slow polarization processes fail to keep up with the rapid field reversal. This leads to clear dispersion, reflected by a decrease in ε' with increasing frequency. Notably, dielectric relaxation phenomena are frequently observed in the dielectric spectra of biochar. This relaxation is likely associated with the hopping conduction of polarized charge carriers within the amorphous carbon matrix of biochar or the reorientation processes of confined charges in its hierarchical pore channels[84].

Tunability through composition, pressure, and doping

-

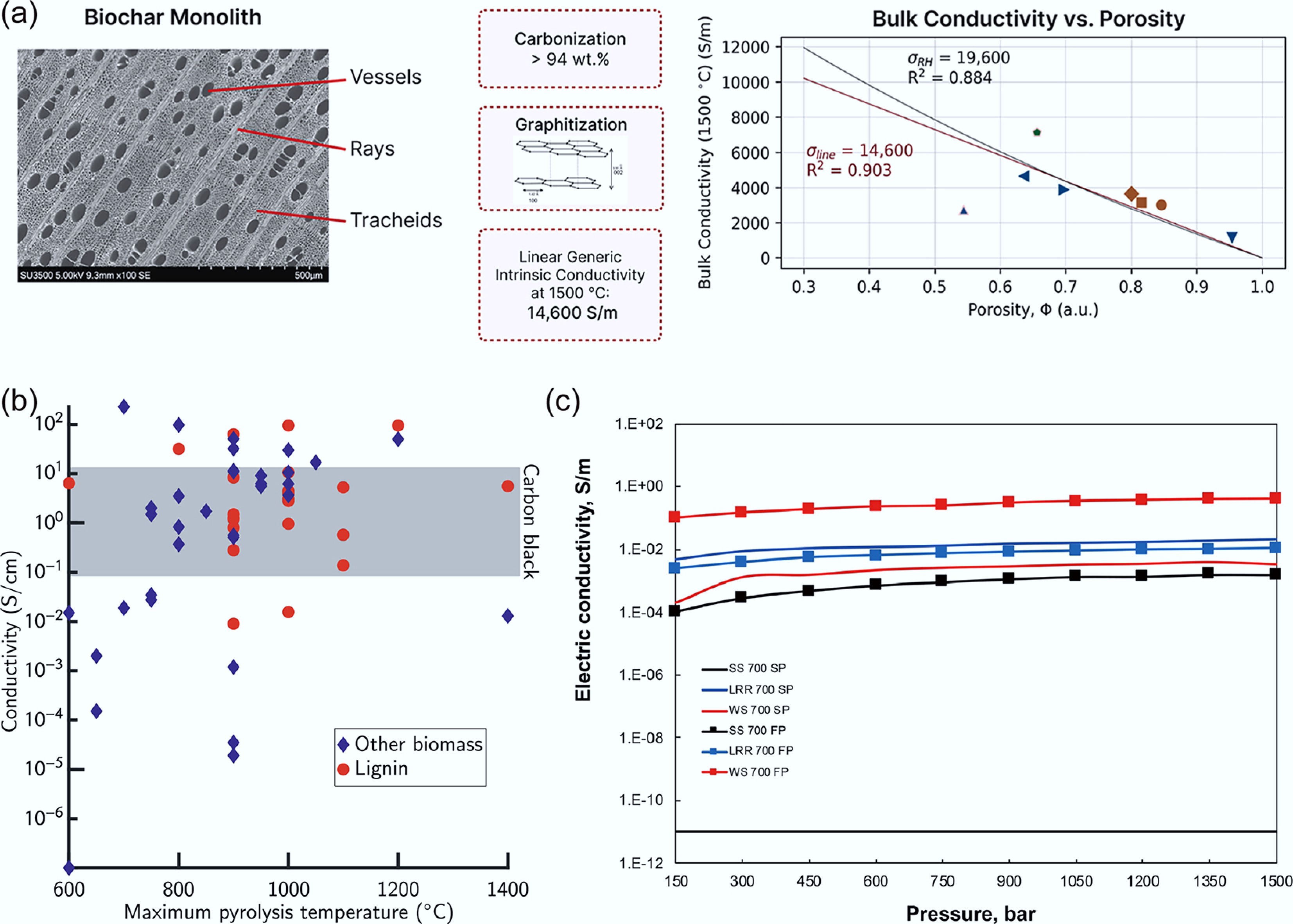

Biochar exhibits an exceptionally broad conductivity range (10−6–105 S/m). This variation is mainly controlled by the feedstock composition across different pyrolysis conditions. For instance, Gabhi et al. reported that raising the carbon content from 86.8 to 93.7 wt% increased biochar conductivity by more than six orders of magnitude. Sugar-maple biochar with 96.2 wt% carbon achieved a peak skeletal conductivity of 343.2 S/m[78]. Further establishing a fundamental property, the same group defined intrinsic conductivity based on the bulk conductivity-density relationship (Fig. 5a). They found that it rises steadily with temperature, independent of wood species. At 1,500 °C, wood biochar reached a conductivity of 14,600 S/m. Bamboo biochar performed even better, attaining 21,000 S/m, owing to its high cellulose content and larger graphitic nanocrystals[76]. Comparative studies on maple and pine biochars produced between 600 and 1,000 °C revealed bulk conductivities of 1–1,000 and 1–350 S/m, respectively. At 1,000 °C, their skeletal conductivities reached ~3,300 and ~2,300 S/m[77]. Significant variability persists even within specific precursor types, as lignin-derived biochars showed a wide conductivity range (0.009–62.96 S/cm) at 900 °C (Fig. 5b). Moreover, applied pressure exhibits a positive correlation with biochar conductivity (Fig. 5c), highlighting another critical operational parameter[79].

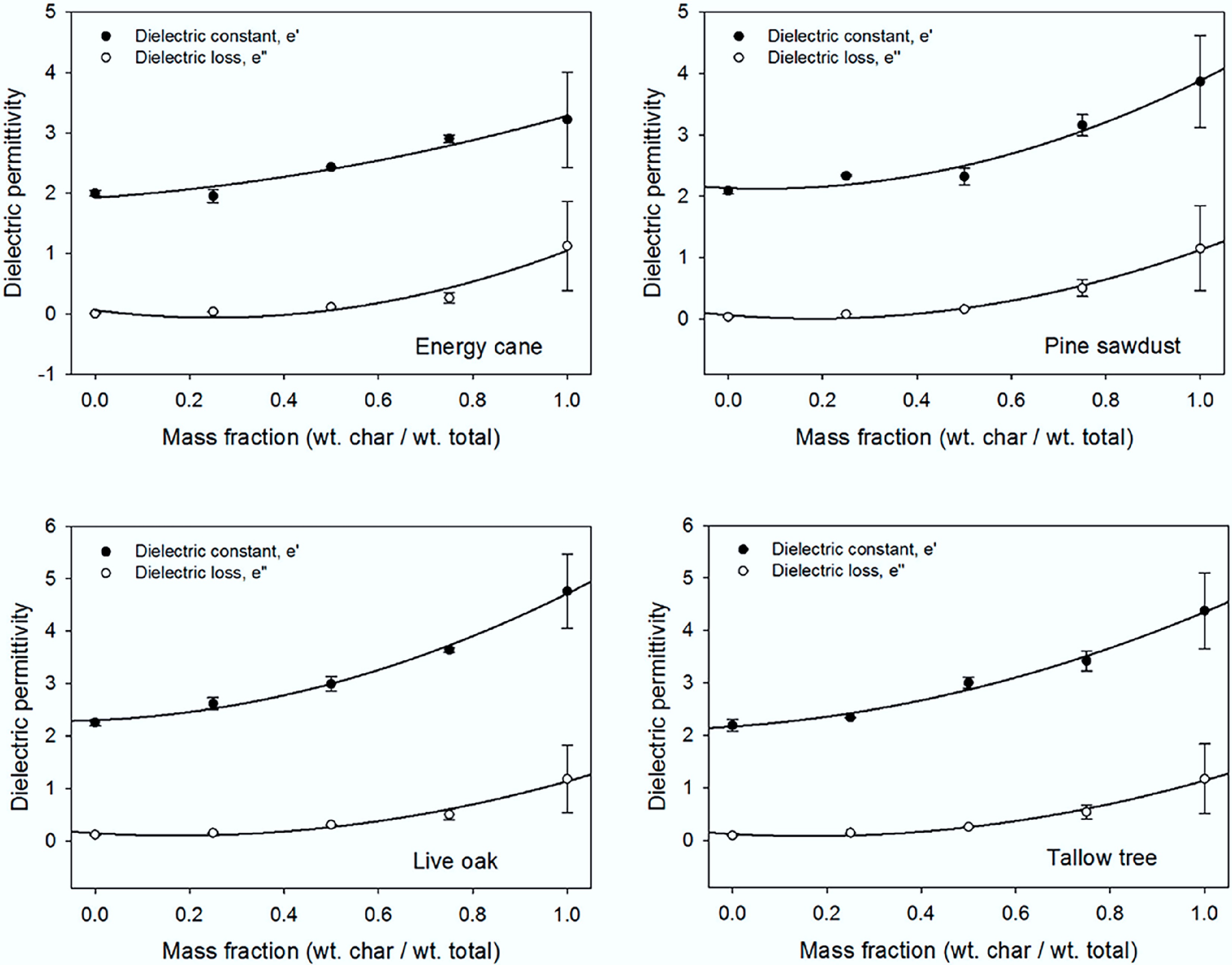

Biochar's frequency-dependent permittivity (2–5 in the GHz range) and tunable loss factor position it as a candidate for microwave absorbers and capacitor materials. Particle size reduction and doping modulate these properties, offering pathways to multifunctional electrothermal composites. Richard et al. pyrolyzed rice husks to produce biochar, which was then ground into five distinct nanoparticle sizes (45–510 nm) using a ball mill. Their investigation revealed a significant enhancement in the dielectric properties as the particle size decreased[85]. Salema et al. reported that the dielectric properties of palm shell biochar are highly frequency-dependent. They observed that the dielectric permittivity decreases with increasing frequency, while the loss factor exhibits an opposite trend. At 2.45 GHz, the dielectric permittivity of the biochar was recorded between 2 and 3[86]. According to Ellison et al., dielectric properties of pulverized biomass and biochar mixtures were presented from 0.5 to 20 GHz at room temperature. The dielectric constant was between 2 and 5 (Fig. 6)[84].

Figure 6.

Dielectric constant and loss factor measurements as a function of biochar content at 2.45 GHz for each biomass[84].

Salema et al. further investigated the dielectric properties of five distinct biomass types (oil palm shell, empty fruit bunch, rice husk, coconut shell, and wood). They reported that the dielectric properties (permittivity and loss factor) decreased slightly in the drying zone (24–200 °C) due to moisture removal and declined further in the pyrolysis zone (200–450 °C) as volatiles were decomposed or released (Fig. 7a). However, a sharp increase was observed when the temperature exceeded 450 °C[87]. Yao et al. also reached similar conclusions. This phenomenon was attributed to three sequential mechanisms, as shown in Fig. 7b: (1) Initial decrease: vaporization of high-permittivity water, reducing dipole count. (2) Further decrease and loss: microwave-induced dipole polarization and friction in polar components (e.g., fructose, –COOH) during the decomposition of biopolymers, with gradual decline as gaseous products (CO2, CO) evolve. (3) Final increase: formation of conductive, porous biochar, whose accumulating fraction significantly enhances both permittivity and loss[88]. Fan et al. further pointed out that the loss tangent angle was 0.01–0.05 in the first two stages. It increased to 0.10–0.25 in the carbonization stage, indicating that the biowaste is a low-loss material[89].

-

Biochar exhibits intrinsic light-absorbing and fluorescent properties, which are driving new advances in environmental photochemistry and analytical sensing. This chapter reviews recent progress in these optical properties of biochar, highlighting its evolution from a passive environmental medium into an effective photosensitizer and fluorescent probe. This overview seeks to provide guiding perspectives for designing advanced biochar-based optoelectronic devices and optical sensing platforms.

Broadband absorption and photothermal conversion

-

Significant progress has been made in understanding biochar's optical absorption, particularly its role as a functional component in photocatalytic composites for enhanced light harvesting. Studies have revealed that biochar effectively enhances light absorption in composites through several key mechanisms: (1) Band-gap narrowing of photocatalytic materials: The composite structure formed between biochar and semiconductors can reduce the band-gap energy[90,91]. This broadening of the light response range enables the utilization of a greater portion of visible light for catalytic reactions. (2) Improved charge separation and transport: Owing to its excellent electrical conductivity, biochar functions as an electron shuttle and reservoir[92], effectively facilitating the transfer of photo-generated electrons from the semiconductor to the biochar, thus significantly suppressing electron-hole pair recombination. This process prolongs charge carrier lifetime and enhances photocatalytic efficiency.

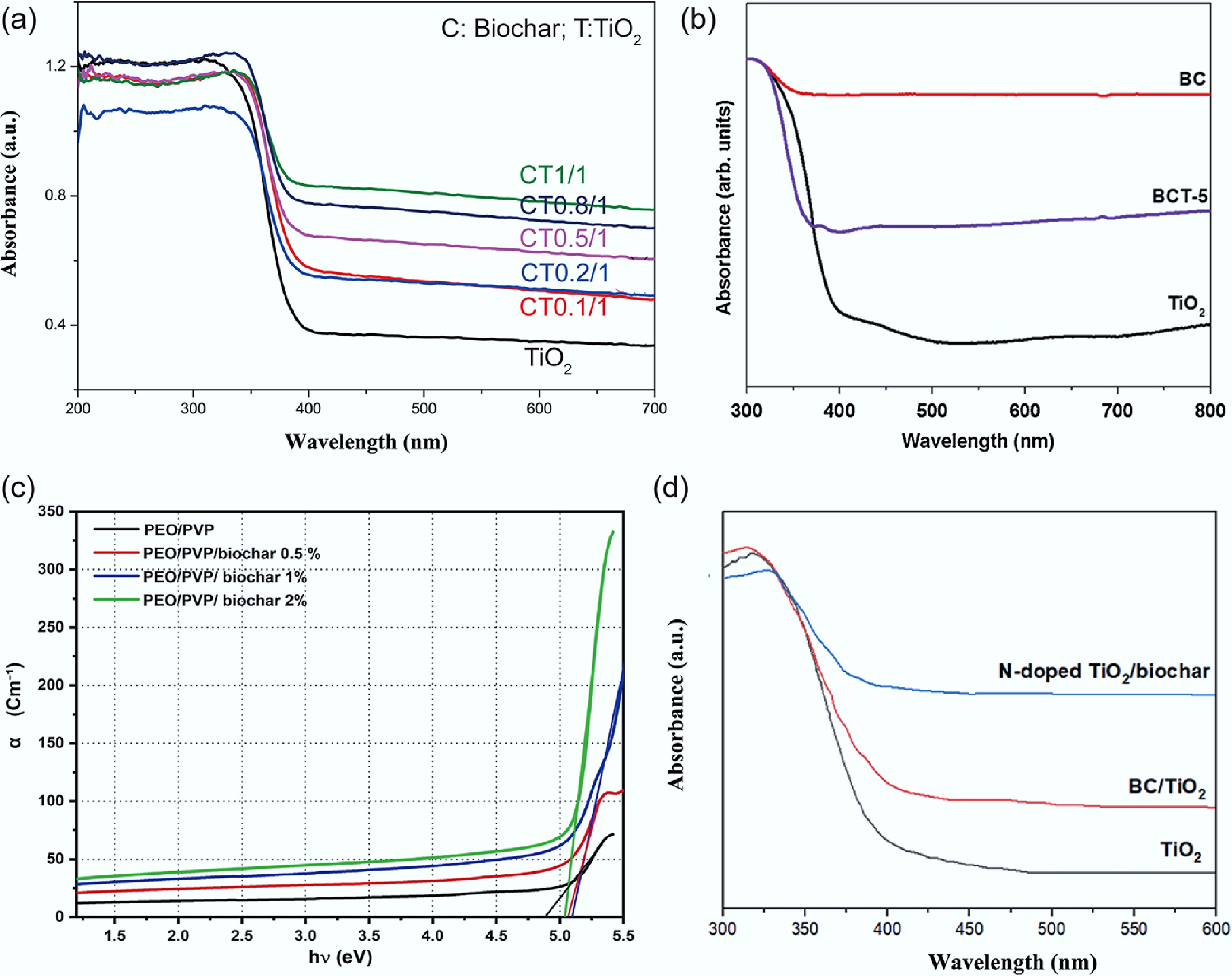

Lu et al. reported that incorporating walnut-shell biochar into a TiO2 composite notably enhanced its visible-light absorption and activity, an effect that intensified with higher biochar loading (Fig. 8a)[93]. Fazal et al. found that all TiO2/biochar composite samples demonstrated markedly enhanced absorbance across the visible spectrum (400–700 nm) compared to pure TiO2 (Fig. 8b)[94]. Atta et al. demonstrated that incorporating 1% biochar into the pristine blend reduced the optical band gap, as confirmed by a reduction in the calculated absorption edge (Ed) from 4.9 to approximately 4.7 eV. They attributed this band-gap narrowing to the formation of localized states within the gap, induced by chemical bonding between the blend and biochar (Fig. 8c)[95]. Furthermore, elemental doping is a viable strategy for modifying biochar to optimize its light-absorbing properties. For instance, Hu et al. reported that the N-doped TiO2/biochar composite exhibited a redshifted visible absorption edge due to band-gap narrowing induced by nitrogen doping (Fig. 8d)[96]. Doping with metal ions can induce crystal-lattice distortion, capture photo-generated electrons, and ultimately narrow the band gap due to the strong reducibility of reduced metals. Zhang et al. successfully synthesized a β-FeOOH/Fe3O4/biochar composite and confirmed the presence of Fe–O–C bonds between β-FeOOH and biochar. This chemical linkage facilitated the transfer of photo-generated electrons, consequently enhancing the photocatalytic activity[97]. In the highly efficient BC/FeOOH/Bi2MoO6 composite fabricated by Xue et al., performance enhancement was primarily attributed to biochar. The excellent conductivity of biochar facilitated electron migration, thereby hindering charge-carrier recombination and improving the overall photocatalytic efficiency[98].

Figure 8.

(a) UV–vis diffuse reflectance spectra of TiO2 and biochar/ TiO2 composites[93]. (b) UV–vis diffuse reflectance spectra of biochar, TiO2, and biochar/TiO2 composites[94]. (c) Absorption coefficient (α) vs photon energy (hν) of PEO/PVP/biochar composite[95]. (d) UV-vis spectra of TiO2, BC/TiO2, and N-doped TiO2/biochar powder[96].

Photoluminescence and defect-state emission mechanisms

-

The photoluminescent properties of biochar primarily originate from its unique microstructure and chemical composition. During the pyrolysis process, biomass components such as lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose undergo carbonization, forming microscopic sp2-hybridized carbon domains. These domains, which resemble structures such as carbon quantum dots or graphene fragments, serve as the primary sources of light emission[99,100]. Simultaneously, abundant surface functional groups (e.g., hydroxyl and carboxyl groups) and heteroatom doping (e.g., nitrogen, sulfur) create defect states or surface states within the energy gap. Upon photoexcitation, these defect states capture electron–hole pairs, whose subsequent recombination generates fluorescence[101]. Notably, biochar commonly exhibits excitation-dependent emission, where the fluorescence color changes with the excitation wavelength. This behavior arises from luminescent sites of different sizes and structures[102,103].

The fluorescence properties of biochar can be effectively modulated through several strategies to meet specific application requirements. The selection of raw materials serves as the foundation. Different plant-based precursors yield biochars with distinct fluorescent characteristics due to their inherent compositional differences. Nava et al. efficiently produced water-soluble fluorescent carbon nanodots (CNDs) within minutes via picosecond-laser ablation of biocarbon sources derived from orange peel, avocado peel, and spent coffee grounds[99]. The avocado-derived CNDs exhibited the highest yield and smallest size (2.2 ± 0.3 nm), displaying an amorphous structure and bright blue-green emission centered at 430 nm under 330 nm excitation. In contrast, CNDs derived from orange peel and spent coffee grounds were larger (5–40 nm), contained partial graphitic phases, and demonstrated significantly weaker fluorescence. Plácido et al. synthesized biochar-derived carbonaceous nanomaterials (BCN) from three types of biochar produced via thermal conversion of biomass: microalgae, rice straw, and sorghum straw. Fluorescence spectroscopy revealed significant differences among the three BCN types. The Stokes shifts of SSB-CN, RSB-CN, and MAB-CN were measured at 109, 90, and 72 nm, respectively, highlighting the distinct optical properties imparted by different biomass precursors[104].

Pyrolysis temperature plays a central role in determining carbon graphitization and surface functional groups. These changes directly influence the fluorescence color and intensity. Huang et al. investigated the effect of pyrolysis temperature on the characteristics of biochar-derived dissolved organic matter (BDOM) and its cadmium (Cd) binding behavior[105]. They found that elevated pyrolysis temperatures enhanced the interaction between protein-like components in BDOM and Cd. When the temperature increased from 300 to 500 °C, the fluorescence quenching efficiency of these components by Cd reached 51.64%. This indicated that higher pyrolysis temperatures promote the complexation capacity of biochar toward heavy metals. Based on a dataset of 480 samples and employing six machine learning models, Chen et al. systematically investigated the relationship between biochar preparation parameters and fluorescence quantum yield (QY)[106]. Their results demonstrated that production parameters exert a more significant influence on QY than feedstock properties. Among four key parameters (pyrolysis temperature, residence time, nitrogen content, and carbon-to-nitrogen ratio), pyrolysis temperature was identified as the most critical determinant for QY.

Furthermore, doping modification represents a powerful tuning approach[107]. Introducing elements such as nitrogen can enhance the surface polarity of biochar materials, promoting interactions with target molecules and consequently modifying their luminescent behavior. A route demonstrated by Zhang et al. valorized Chinese herbal medicine residues by converting them into porous carbon materials and carbon dots. Through self-doping, which utilized the residue's inherent nitrogen, the carbon dots attained a quantum yield of 36.17%[108]. Marpongahtun et al. synthesized carbon dots (CDs) and nitrogen-doped CDs (NCDs) from candlenut shell biomass via a hydrothermal method (230 °C, 6 h) using ethylenediamine as a nitrogen dopant (4%–12% v/v)[101]. Photoluminescence characterization revealed that undoped CDs exhibited an emission peak at 494 nm with a quantum yield (QY) of 18%, while 8% NCDs showed the strongest fluorescence at 498 nm and achieved the highest QY of 27%. This result demonstrated that the luminescence performance was enhanced through optimal nitrogen doping. Precise control over these parameters enables tailored design of biochar fluorescence, including emission color (spanning blue to red and even the near-infrared region) and quantum efficiency.

Emerging optical and sensing applications

-

Owing to its tunable optical properties, excellent biocompatibility, and low toxicity, biochar demonstrates broad application potential across multiple fields. Biochar's efficient photothermal conversion makes it well-suited for interfacial solar evaporators. This offers a promising pathway for sustainable seawater desalination[109−112]. In environmental monitoring, functionalized fluorescent biochar serves as a sensitive probe for detecting heavy metal ions (e.g., Hg2+[113], Cd2+[105], Fe3+[114]) and organic pollutants[108]. Upon interaction between its luminescent sites and these contaminants, fluorescence quenching or enhancement occurs, enabling highly selective and sensitive detection. In biomedicine, biochar, particularly in the form of carbon dots, acts as a safe fluorescent probe for cellular imaging, in vivo tracking, and even drug delivery systems due to its outstanding biocompatibility[104,115]. Additionally, fluorescent biochar provides a low-cost and environmentally friendly luminescent material for optoelectronic devices. It can serve in light-emitting diodes (LEDs) phosphor layers or be combined with semiconductors to improve photoactivity[116−118].

-

The physical properties of biochar are inherently interlinked through shared structural elements. Hierarchical porosity simultaneously governs adsorption capacity, heat transfer, and mechanical stability. Graphitic ordering underlies both electrical and thermal conductivities, while mechanical resilience supports electrochemical durability. These correlations define biochar as a multifunctional carbon system rather than a single-purpose material.

Cross-property coupling and hierarchical control

-

The multifunctional behavior of biochar originates from its inherently hierarchical structure, which spans atomic, microstructural, and macroscopic scales. At the atomic scale, sp2/sp3 carbon domains, defects, and heteroatom dopants control electron delocalization, phonon transport, and surface reactivity. These factors collectively determine the material's electrical, thermal, and chemical behavior. Biochar features interconnected micro-, meso-, and macropores. Their size distribution, connectivity, and wall morphology determine adsorption, transport efficiency, mechanical stiffness, and thermal insulation. Micropores contribute high surface area, mesopores facilitate diffusion and phonon scattering, and macropores provide mechanical load-bearing pathways. At the macroscopic level, bulk density, anisotropy, and structural continuity further modulate long-range transport and mechanical integrity. These multiscale features are not independent. Instead, they form a tightly coupled structural network in which modifications at one scale inevitably influence properties at others. Consequently, biochar's hierarchical architecture co-regulates its adsorption, thermal, electrical, and mechanical behaviors, making it a prime example of a material governed by cross-property coupling.

Mechanical–thermal–electrical synergies

-

Biochar exhibits a unique combination of mechanical robustness, thermal insulation, and electrical conductivity—properties that are typically difficult to achieve simultaneously in conventional materials. These synergies arise from the interplay between the sp2-hybridized carbon network and the hierarchical pore structure formed during pyrolysis. The interconnected graphitic domains provide continuous pathways for electron transport while simultaneously serving as a mechanically supportive skeleton capable of distributing stress and preventing structural collapse. Meanwhile, the porous architecture introduces abundant air-filled voids and interface boundaries that strongly scatter phonons, thereby suppressing thermal conductivity without significantly disrupting electrical percolation. This selective decoupling of electron and phonon transport enables biochar to maintain electrical conductivity even under conditions where thermal conduction is minimized. Furthermore, the carbon walls that facilitate electron and phonon transport also contribute to mechanical stiffness, allowing the material to retain structural integrity under compression or cyclic loading. These mechanisms act synergistically, allowing electrical, thermal, and mechanical behaviors to reinforce rather than compete. As a result, biochar emerges as a strong multifunctional candidate for energy management, EMI shielding, and integrated structural–electrical applications.

Although strong cross-property synergies are well-documented across adsorption, thermal, electrical, mechanical, and electrochemical behaviors, it must be acknowledged that the current biochar literature remains highly fragmented in terms of experimental design. Most studies characterize only one or two physical properties at a time, often using different feedstocks, activation routes, and thermochemical conditions. As a result, direct multi-property measurements on the same biochar system—together with quantitative correlations linking multiple properties through unified descriptors such as degree of graphitization, pore connectivity, or defect density—are still largely absent. This limitation reflects the broader research landscape rather than any specific methodological constraint, as different physical properties are typically investigated by separate research communities with distinct characterization infrastructures. The Physical Genome framework proposed here aims to synthesize these dispersed findings into a coherent conceptual model and to highlight the need for future multi-property datasets that can quantitatively validate these cross-property linkages.

Performance conflicts and strategies for synergistic optimization

-

Despite its inherent synergies, biochar also exhibits several performance conflicts arising from the competing structural requirements of different functionalities. For example, increasing porosity enhances adsorption capacity and thermal insulation but often reduces mechanical strength due to thinner pore walls. Similarly, higher degrees of graphitization improve electrical and thermal conductivity but may diminish surface area and limit adsorption or catalytic activity. These conflicts highlight the need for rational structural design strategies that balance or decouple competing properties. Hierarchical pore engineering offers one solution by assigning distinct roles to micro-, meso-, and macro-pores, enabling simultaneous optimization of adsorption, diffusion, and mechanical support. Dual-network architectures, in which graphitic domains provide conductive pathways while amorphous carbon regions offer mechanical buffering, further mitigate trade-offs between conductivity and structural stability. Gradient or functionally partitioned structures can spatially separate thermal insulation, electrical conduction, and mechanical reinforcement, allowing each region to be optimized independently. Additionally, defect and interface engineering can fine-tune electronic structure and interfacial polarization without compromising mechanical integrity. Through these strategies, biochar can overcome intrinsic performance conflicts and achieve synergistic multifunctionality tailored to specific application demands.

Multifunctional design principles and application-oriented property integration

-

Biochar's cross-property synergies allow it to function as a versatile platform for multifunctional applications. Achieving this requires careful structural engineering to meet specific performance needs. In electrochemical energy storage, the combination of a conductive carbon framework, hierarchical porosity, and mechanical resilience supports rapid electron transport, efficient ion diffusion, and stable cycling under mechanical and thermal stresses. In photoelectrical and catalytic systems, the porous architecture provides high-dispersion support and abundant reactive interfaces. Graphitic domains further aid charge separation and electron extraction, collectively enhancing catalytic efficiency. For electromagnetic interference shielding, biochar benefits from its conductive network, defect-induced polarization, and porous interfaces, which together promote multiple attenuation mechanisms. In thermal management, the combination of low thermal conductivity and mechanical stability enables biochar to function as a lightweight, structurally robust insulator. Environmental remediation applications further leverage its high surface area, tunable surface chemistry, and hierarchical porosity. These diverse functionalities illustrate how biochar's multiscale structure can be strategically manipulated to integrate adsorption, conduction, insulation, mechanical support, and catalytic activity within a single material system.

To translate the empirical trends summarized in this review into actionable engineering strategies, we introduce a decision-oriented design framework grounded in the Physical Genome concept. In this framework, lignocellulosic composition, inorganic content, and macromolecular architecture of the feedstock determine the initial distribution of precursor 'genes'. Pyrolysis temperature, heating rate, residence time, activation chemistry, and post-treatments regulate the expression of these genes into specific structural features—such as pore topology, graphitization level, and defect density. These structural units are treated as tunable design variables whose evolution can be predicted and steered through synthesis choices.

Building on this foundation, application-oriented design pathways are outlined that specify which structural units should be prioritized for different functional targets. Adsorption-dominated environmental applications require high microporosity, abundant edge defects, and accessible surface functional groups. Photothermal conversion benefits from enhanced graphitic domains, broadband absorptive features, and hierarchical pore networks that facilitate light trapping. Thermal management applications prioritize interconnected meso–macropores and moderate graphitization to balance conductivity and structural integrity. Electrochemical stability relies on mechanically robust pore architectures, low defect-induced degradation pathways, and stable mineral–carbon interfaces. These pathways provide explicit guidance on how to match structural 'genes' with performance requirements.

Representative examples further illustrate how this framework informs synthesis decisions. For instance, high adsorption capacity can be achieved by choosing feedstocks rich in hemicellulose. Low-to-moderate pyrolysis temperatures (450–650 °C) help preserve microporosity. Subsequent CO2 activation further improves pore connectivity. Strong photothermal performance benefits from lignin-rich feedstocks and high-temperature pyrolysis (> 800 °C), which promote graphitization. KOH activation can be added to create hierarchical pores that enhance light absorption. For electrochemical stability, moderate pyrolysis temperatures (600–800 °C) are preferred. Maintaining certain mineral phases or applying post-treatment stabilization helps strengthen mechanical robustness and prevent structural collapse during cycling. These examples demonstrate how the physical genome framework can be operationalized into stepwise, application-specific design logic for precision engineering of multifunctional biochar.

-

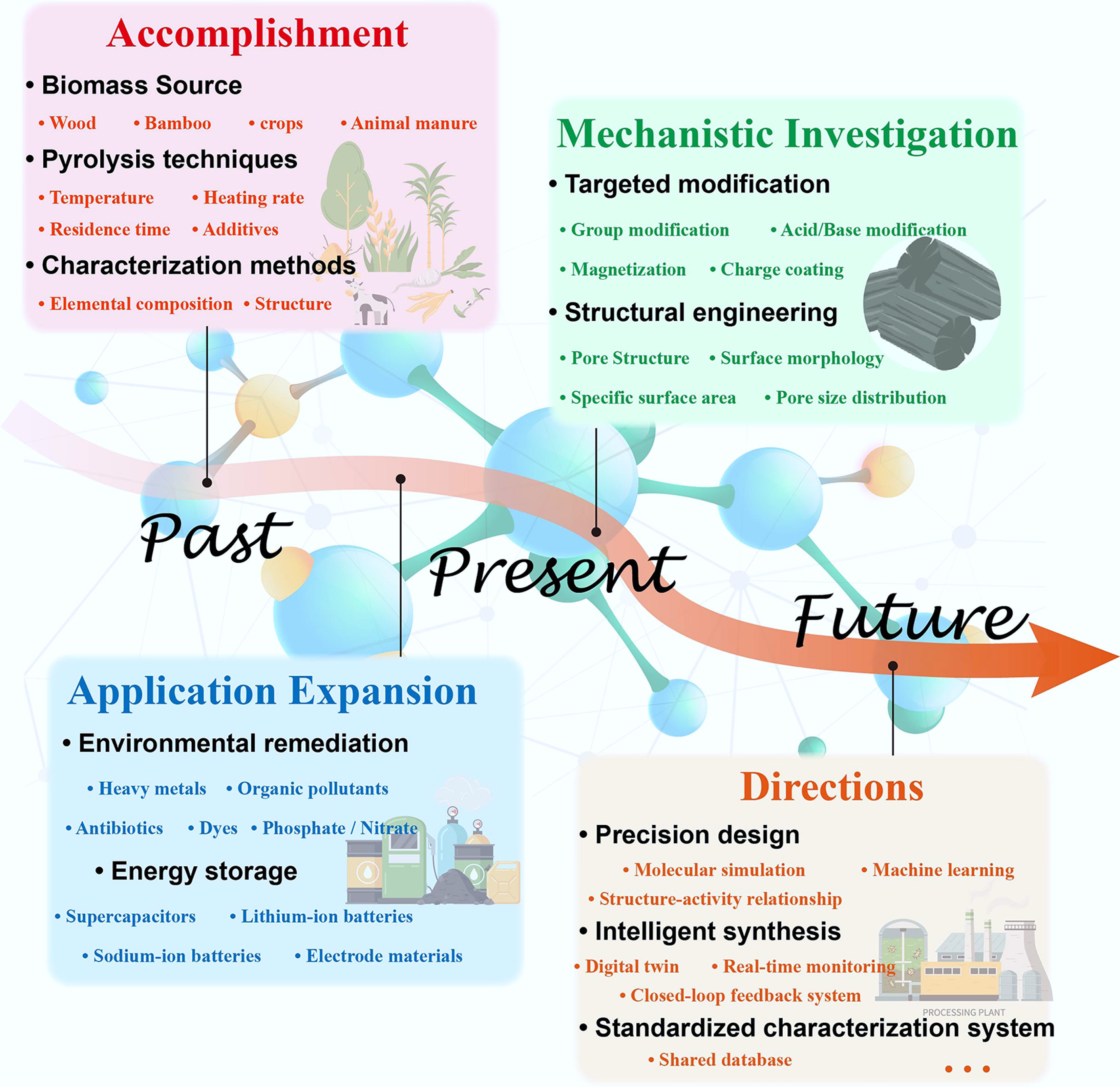

Biochar research holds significant implications for achieving sustainable societal development. Figure 9 outlines the development roadmap of biochar. The field has progressed past foundational challenges, including synthesis methodologies and basic characterization, which have now reached a stage of maturity. The research paradigm has consequently shifted toward a deeper mechanistic investigation and the expansion of application domains.

Current biochar research faces several critical challenges that hinder its transition from fundamental studies to industrial applications. The absence of standardized testing protocols makes data from different research groups difficult to compare, which directly limits accurate property assessment and the formulation of reliable application guidelines. Theoretically, the correlation mechanisms between microstructure and macroscopic properties remain incompletely elucidated, particularly regarding multi-scale structure–property relationships. This knowledge gap results in a considerable degree of empiricism in material design. From a technical perspective, the synergistic regulation of multiple properties presents substantial challenges, as enhancing one characteristic (e.g., electrical conductivity) often occurs at the expense of others (e.g., mechanical strength). For practical applications, research on long-term performance in complex environments remains insufficient. This is especially true for studies on aging and ecological impacts in real soil and aquatic matrices. To address these challenges, future biochar research should systematically advance along the following key directions.

Standardization and mechanistic modeling

-

The lack of unified testing protocols impedes cross-study comparability. Consequently, there is an urgent need to establish standardized characterization systems and develop shared databases covering the entire 'precursor-process-structure-property' chain. This foundation will provide essential benchmarks and data support for material development. Simultaneously, multi-scale correlations between microstructure and macroscopic performance remain partially empirical. Coupled modeling and in situ analytics are needed to capture dynamic transformations during pyrolysis.

Data-driven and machine-learning approaches

-

Enhancing one property often compromises another. By combining data-driven methods such as machine learning, quantitative models connecting preparation parameters, structure, and performance can be established, revealing balanced synthesis pathways. This advancement will facilitate functional customization for specific application scenarios (e.g., high-sensitivity sensing and efficient energy storage). Particular attention should be paid to multi-property optimization strategies, aiming to develop green preparation processes that can synergistically regulate pore structure, surface chemistry, and crystalline architecture.

Emerging frontiers: energy systems, sensing, and beyond

-

From an application-expansion perspective, innovative applications in frontier interdisciplinary fields should be actively explored. Beyond traditional environmental remediation and agricultural utilization, biochar demonstrates potential value in emerging sectors, including intelligent sensing, thermal management, electromagnetic shielding, and even space technology. Realizing this potential requires strengthened interdisciplinary collaboration to generate new research directions and application scenarios through knowledge integration.

By systematically addressing these challenges and pursuing sustained exploration along these directions, biochar research will progressively evolve from its current empirically dominated phase toward a new stage of precision control. This transition will provide a strong foundation for innovative applications in high-technology fields, increase the value of biochar, and promote the high-value utilization of carbon resources toward sustainable development.

Perspective: toward predictive biochar design

-

A closed-loop framework is envisioned that couples multiscale modeling, in situ/operando analytics, and machine learning to steer synthesis toward target property vectors. The 'physical genome' comprises tunable structural genes—graphitic domain size, pore hierarchy, and heteroatom/inorganic interfaces—that jointly modulate charge, heat, light, and mechanical responses.

The following rules guide the design: (1) maximize contiguous sp2 pathways for co-optimized electrical and thermal transport; (2) co-engineer micro–meso porosity to balance surface area and strength; (3) exploit anisotropy to manage conduction; and (4) leverage catalytic graphitization to tune defects and order. This predictive workflow will accelerate the transition from empirical carbonization to precision-engineered, application-specific biochar for energy, photothermal, and EMI applications. It also reveals a tunable 'physical genome' that connects atomic bonding and hierarchical porosity to the mechanical, thermal, electrical, and optical behaviors of biochar across scales.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Yating Ji: writing – original draft, data curation. Donald W. Kirk: writing – review & editing. Zaisheng Cai: funding acquisition, writing – review & editing, supervision. Charles Q. Jia: funding acquisition, writing – review & editing, supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable requests.

-

This work was supported by Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22176031), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities and Graduate Student Innovation Fund of Donghua University (Grant No. CUSF-DH-D2024027), and the China Scholarship Council (Grant No. 202406630052).

-

The authors declare that they have no competing interests that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. The authors acknowledge that they have referenced their own works where relevant to the review paper.

-

Integrates biochar's mechanical, thermal, electrical, and optical properties into a unified framework.

Establishes structure–property–function principles for rational biochar design.

Outlines data-driven and precision-engineering pathways for next-generation biochar.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Ji Y, Kirk DW, Cai Z, Jia CQ. 2026. Unraveling the physical genome of biochar. Biochar X 2: e003 doi: 10.48130/bchax-0026-0003

Unraveling the physical genome of biochar

- Received: 09 December 2025

- Revised: 27 December 2025

- Accepted: 10 January 2026

- Published online: 29 January 2026

Abstract: Biochar, a porous carbonaceous material produced through the thermochemical conversion of biomass, is garnering significant attention for its critical roles in carbon sequestration, sustainable energy solutions, and advanced materials engineering. The strategic and precise manipulation of its intrinsic physical properties—such as hierarchical porosity, mechanical robustness, thermal conductivity, electrical transport behavior, and tunable optical response—has now emerged as a fundamental enabler for designing next-generation multifunctional carbon systems. This review provides a comprehensive, integrated, and multiscale examination of these physical characteristics, with a particular focus on elucidating the complex, often synergistic relationships among them. By establishing robust correlations spanning from the atomic-level molecular structure and chemical functionality to the microstructural morphology and ultimately the macroscopic performance, a coherent structure-property-function framework is constructed. This framework is essential for guiding the rational design of biochar-based materials. Furthermore, persistent knowledge gaps and the challenges posed by these gaps are critically highlighted. Finally, future pathways toward precision-engineered biochar for high-value applications in energy storage, photothermal conversion, environmental remediation, and beyond are proposed.